Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) are located in the innermost layer of the retina and are the only retinal output neurons, conveying light information to the main retinorecipient target regions of the brain responsible for the image- and non-image-forming visual functions. There are well over twenty RGC types, each with its own dendritic morphology and physiological characteristics, target territories and visual functions. The study of the responses of RGCs to various injury-induced or inherited retinal degenerations requires the specific identification of these neuron types. RGCs share their anatomical location in the RGC layer with the displaced amacrine cells, a population as numerous as the population of RGCs itself, with overlapping soma sizes. Consequently, classical morphological methods do not allow distinction between these two classes of retinal neurons. Up to now, RGCs have been identified mainly with retrograde tracers applied to their principal retinorecipient target nuclei in the brain, the superior colliculi (SCi), or applied to their main axonal output, the optic nerve (ON). These methods, although the most efficient to label the great majority of RGCs, do not distinguish between different RGC types. Retrogradely transported tracers applied to the ON result in massive retrograde labelling of RGCs, while tracer application to the SCi labels most RGCs projecting to these nuclei as well as to neighbouring areas. Indeed, injection into the optic tract or tracer application over the SCi may result in spurious labelling of neurons located in neighbouring areas (Vidal-Sanz et al., 2002; Valiente-Soriano et al., 2014).

Intrinsically photosensitive RGCs (ipRGCs) constitute a novel type of RGC recently characterized by their capability to detect light and act as photoreceptors; they express the photosensitive pigment melanopsin (ipRGCs are also known as melanopsin-expressing m+ RGCs), which allows them to absorb and process ambient light information (Lucas et al., 2014). A large body of work has shown the importance of this type of RGC, which mediates a number of non-image-forming visual functions, such as: photo-entrainment of circadian rhythms; light suppression of melatonin secretion; masking behaviour; cognition, wakefulness and sleep; the pupillary light reflex; and the postillumination pupil response. Several subtypes of ipRGCs have been described (M1-M5) with a recently described melanopsin-expressing interneuron (Valiente-Soriano et al., 2014), and all ipRGCs present intrinsic photo-responses with a λmax close to melanopsin's λmax. However, melanopsin antibodies only readily identify the M1, M2 and some of M3 subtypes, but none of the M4 or M5 subtypes. m+ RGCs are characterized by their soma size, the largest among RGCs (rats: diameter range 10–21 μm with mean diameter of 15 μm for pigmented and 12.3 μm for albino rats; mice: diameter range 9.5–21.4 μm with a mean diameter of 13.5 μm for pigmented and 14.8 μm for albino mice). In addition, m+ RGCs have characteristic dendritic morphology and stratification patterns within the inner synaptic layer of the retina, and unique light-evoked electrophysiological responses. m+ RGCs are sparse and constitute approximately 2–3% of the entire RGC population in rodents (2.5 and 2.7% in adult pigmented and albino rats, respectively, or 2.5 and 2.1%, respectively, in adult pigmented and albino mice) (Nadal-Nicolás et al., 2014; Valiente-Soriano et al., 2014). Topographic analysis reveals that m+ RGCs are distributed in a complementary fashion with respect to the distribution of Brn3a+ RGCs, showing maximal densities in the superior retina in rats and mice, although there are subtle differences in the location of peak densities (the temporal retina for pigmented mice and albino rat, and the superior retina for albino mice and pigmented rats). Although the great majority of m+ RGCs are located in the GC layer, a small proportion are displaced to the inner nuclear layer (2.2% and 8.7% in albino and pigmented rats, respectively; 5% and 14% in albino and pigmented mice, respectively (Nadal-Nicolás et al., 2014; Valiente-Soriano et al., 2014).

Various laboratories have investigated the responses of m+ RGCs to different diseases such as inherited mitochondrial optic neuropathies or experimentally induced retinal injuries (including ON lesion and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-mediated excitotoxicity) and have found these cells to be more resistant to injury than the rest of the RGC population. However, the responses of these neurons in glaucoma or animal models of the disease have not yielded homogeneous results. Rodent models of ocular hypertension (OHT) have reported altered functions such as, circadian rhythm regulation, pupillary light reflex, locomotor activity rhythm and light suppression of melatonin secretion that imply loss of m+ RGCs, while other studies have indicated a particular resilience of these cells to this type of injury. Moreover, patients with advanced glaucoma present abnormal circadian rhythm of melatonin secretion and of light-induced melatonin suppression, as well as abnormal post-illumination pupil response, also suggesting loss of function mediated by m+ RGCs (for review see Cui et al, 2015; Valiente-Soriano et al., 2015a, b).

Neurodegenerative diseases such as glaucoma are characterized by the progressive loss of neurons with concomitant neurological deficits that lead to irreversible and permanent loss of function. Glaucoma is the most common optic neuropathy responsible for the loss of vision in developed countries and is characterized by an insidious but slowly advancing degeneration of RGCs, defects of the optic nerve head and visual field anomalies that may progress to blindness. One of the most important risk factors for development of glaucoma is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), currently the only factor that can be modified with medical and/or surgical treatment in an attempt to halt disease progression. However, other risk factors may be responsible for glaucoma progression in patients with normal IOP.

Because in glaucoma the actual cause of RGC loss is unknown and the exact mechanisms responsible for OHT-induced RGC death are not completely understood, alternatives for treatment other than lowering IOP suggest therapeutic interventions aimed at slowing or halting the progression of cell death may be important, something that has been termed neuroprotection. A first indication of the potential for prevention of injury-induced RGC loss was obtained with the use of peripheral nerve grafts attached to the ocular stump of the intraorbitally transected ON (Villegas-Pérez et al., 1998). ON injury leads to a massive and rapid loss of RGCs, but this may be prevented at least in part with grafts of autologous peripheral nerve segments. Further studies explored whether neurotrophic factors produced by denervated Schwan cells, such as brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) or neurotrophin 4/5, could replicate the rescuing effects observed with the peripheral nerve segments (Vidal-Sanz et al., 2000; Lindqvist et al., 2004). Indeed, among the neurotrophic factors tested, BDNF has been proven to be the most effective in a number of experimental models of injury-induced RGC loss, including OHT-induced retinal degeneration (Wilson and Di Polo, 2012).

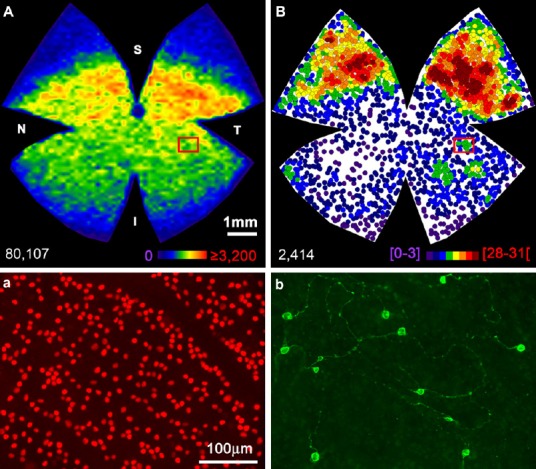

To gain insight into the responses of RGCs to retinal damage and neuroprotection in rodent models of OHT, we have taken advantage of a number of modern tools recently developed in our laboratory to count and image entire neuronal populations of the retina, in combination with retrograde tracers and molecular markers to identify different types of RGCs and thus ascertain their specific responses. At present two reliable molecular markers allow identification of the m+ RGCs and the remaining types of RGCs. Brn3a is expressed in adult albino rats by all RGCs except m+ RGCs and one half of the ipsilaterally projecting RGCs (Nadal-Nicolás et al., 2014; Figure 1A), whereas anti-melanopsin antibodies identify the vast majority of ipRGCs subtypes (Nadal-Nicolás et al., 2014; Valiente-Soriano et al., 2015; Figure 1B). Thus, double immunodetection of Brn3a and melanopsin allows the parallel and independent study of the general RGC population (Brn3a+ RGCs; Figure 1a) and ipRGCs (m+ RGCs; Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution and total number of Brn3a+RGCs and m+RGCs.

(A) Isodensity map showing the distribution of Brn3a+RGCs in a naïve, left adult albino rat retina. (B) Neighbor map showing the distribution of m+RGCs in the same retina. Magnifications from the superior (a, b) retina showing Brn3a (a) and melanopsin (b) RGCs. At the bottom of each map is shown the total number of cells counted. Colour scale bar in A goes from 0 (purple) to the maximum (red) which is ≥ 4,800 Brn3a+RGCs/mm2. The colour scale in B goes from 0 (purple) to 31 or more (red) neighbors in a radius of 0.165 mm. S: Superior; T: temporal; I: inferior; N: nasal. Scale bar: 500 μm. RGCs: Retinal ganglion cells.

We have recently evaluated the responses of m+ RGCs and of the rest of the RGC population to OHT-induced retinal injury and the neuroprotective effect of BDNF. In adult albino rats and pigmented mice, OHT was induced by laser photocoagulation of the limbal tissues, and animals were examined at different survival intervals ranging from 12 days to 4 weeks. In these studies, RGCs were identified with fluorogold® (FG) applied to both SCi one week prior to animal processing, to identify RGCs with an active retrograde axonal transport; melanopsin or Brn3a antibodies were also used to identify ipRGCs or the remaining RGCs, respectively. These tools have allowed the comparison, for the first time within the same retina, of the responses of these neurons to injury and neuroprotection. m+ RGCs and Brn3a+ RGCs die in similar proportions, but they show a different topography of loss throughout the retina. In adult mice, the proportions of m+ RGCs or Brn3a+ RGCs surviving at 2 and 4 weeks were 66% or 60% and 41% or 47%, respectively, while in adult rats, the proportions of surviving m+ RGCs or Brn3a+ RGCs at 12 and 15 days were 50% or 56% and 51% or 46%, respectively (Valiente-Soriano et al., 2015a, b). Thus, in mice and rats, OHT induced a similar degree of loss in both RGC populations. However, one typical feature of the limbal laser-photocoagulation-induced OHT-model is the presence of a sectorial loss of RGCs together with early damage of axons at the level of the ON head and slow degeneration of the RGC somas (Vidal-Sanz et al., 2012). While the general non-ipRGC population, including the small population of RGCs displaced to the inner nuclear layer (Nadal-Nicolás et al., 2014) shows a sectorial, pie-shaped topographical loss of RGCs, m+ RGCs show a different, rather diffuse pattern of loss both in adult mice and rats (Valiente-Soriano et al., 2015a, b).

m+ RGCs and Brn3a+ RGCs also differ in their response to BDNF-induced neuroprotection; while the general RGC population (Brn3a+) is amenable to BDNF-induced rescue, m+ RGCs are not. Following laser photocoagulation of the limbal and episcleral veins in adult rats, eyes were treated with an intravitreal injection of saline or 5μg BDNF, and analysed at 12 or 15 days later, at which time points BDNF-rescuing effects have been shown to be most effective. BDNF afforded a significant neuroprotection of the general population of RGCs against OHT-induced retinal injury – approximately 38% or 25% of the Brn3a+ RGCs were rescued at 12 or 15 days when compared with corresponding vehicle-treated groups (Valiente-Soriano et al., 2015a) a neuroprotective finding that confirms previous reports from other laboratories. It is presently thought that, following OHT, RGCs may suffer an alteration of their retrograde axonal transport in bundles of axons somewhere at the level of the optic nerve head; the exogenous administration of BDNF to injured RGCs replaces the target-derived neurotrophin of which these neurons have been deprived. At present we do not know if this neurotrophin-derived rescue could last for longer time intervals, as has been shown in experimental situations in which RGCs established permanent synaptic connections with target regions in the brain (Vidal-Sanz et al, 2002). However, a surprising finding in these experiments was that in these same retinas there was not significant neuroprotection of m+ RGCs in the BDNF-treated groups (Valiente-Soriano et al., 2015). BDNF activates intracellular pathways through their specific high-affinity TrkB receptor; it is currently not known if m+ RGCs express TrkB (Valiente-Soriano et al, 2015).

Comparatively, m+ RGCs represent only a minute proportion of the RGC population and yet the availability of molecular markers to identify such RGCs has promoted rapid knowledge not only of their morphological and physiological properties, but also of their unique responses to various types of induced retinal injury or inherited diseases. New discoveries or characterization of molecular markers for additional, specific types of RGCs may allow further characterization of the responses of different types of RGCs to axonal injury, including neuronal survival, axonal regeneration, synapse formation and re-establishment of function.

This research is supported by Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness: SAF-2012-38328; ISCIII-FEDER “Una manera de hacer Europa” PI13/01266, PI13/00643, RETICS: RD12/0034/0014.

References

- Cui Q, Ren C, Sollars PJ, Pickard GE, So KF. The injury resistant ability of melanopsin-expressing intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. Neuroscience. 2015;284:845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist N, Peinado-Ramónn P, Vidal-Sanz M, Hallböök F. GDNF, Ret, GFRalpha1 and 2 in the adult rat retino-tectal system after optic nerve transection. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas RJ, Peirson SN, Berson DM, Brown TM, Cooper HM, Czeisler CA, Figueiro MG, Gamlin PD, Lockley SW, O’Hagan JB, Price LL, Provencio I, Skene DJ, Brainard GC. Measuring and using light in the melanopsin age. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal-Nicolás FM, Salinas-Navarro M, Jiménez-López M, Sobrado-Calvo P, Villegas-Pérez MP, Vidal-Sanz M, Agudo-Barriuso M. Displaced retinal ganglion cells in albino and pigmented rats. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:99. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Soriano FJ, García-Ayuso D, Ortín-Martínez A, Jiménez-López M, Galindo-Romero C, Villegas-Pérez MP, Agudo-Barriuso M, Vugler AA, Vidal-Sanz M. Distribution of melanopsin positive neurons in pigmented and albino mice: evidence for melanopsin interneurons in the mouse retina. Front Neuroanat. 2014;8:131. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Soriano FJ, Nadal-Nicolás FM, Salinas-Navarro M, Jiménez-López M, Bernal-Garro JM, Villegas-Pérez MP, Agudo-Barriuso M, Vidal-Sanz M. BDNF rescues RGCs but not intrinsically photosensitive RGCs in ocular hypertensive albino rat retinas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015a;56:1924–1936. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-16454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Soriano FJ, Salinas-Navarro M, Jiménez López M, Alarcón-Martínez L, Ortín-Martínez A, Bernal-Garro JM, Avilés-Trigueros M, Agudo-Barriuso M, Villegas-Pérez MP, Vidal-Sanz M. Effects of ocular hypertension in the visual system of pigmented mice. PLoS One. 2015b;10:e0121134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Sanz M, Lafuente M, Sobrado-Calvo P, Selles-Navarro I, Rodriguez E, Mayor-Torroglosa S, Villegas-Perez MP. Death and neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells after different types of injury. Neurotox Res. 2000;2:215–227. doi: 10.1007/BF03033795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Sanz M, Avilés-Trigueros M, Whiteley SJ, Sauvé Y, Lund RD. Reinnervation of the pretectum in adult rats by regenerated retinal ganglion cell axons: anatomical and functional studies. Prog Brain Res. 2002;137:443–452. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)37035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Sanz M, Salinas-Navarro M, Nadal-Nicolás FM, Alarcón-Martínez L, Valiente-Soriano FJ, de Imperial JM, Avilés-Trigueros M, Agudo-Barriuso M, Villegas-Pérez MP. Understanding glaucomatous damage: anatomical and functional data from ocular hypertensive rodent retinas. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegas-Pérez MP, Vidal-Sanz M, Bray GM, Aguayo AJ. Influences of peripheral nerve grafts on the survival and regrowth of axotomized retinal ganglion cells in adult rats. J Neurosci. 1988;8:265–280. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-01-00265.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AM, Di Polo A. Gene therapy for retinal ganglion cell neuroprotection in glaucoma. Gene Ther. 2012;19:127–136. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]