Abstract

Huntington’s disease (HD) is caused by a polyglutamine (polyQ) domain that is expanded beyond a critical threshold near the N-terminus of the huningtin (htt) protein, directly leading to htt aggregation. While full-length htt is a large (on the order of ~350 kDa) protein, it is proteolyzed into a variety of N-terminal fragments that accumulate in oligomers, fibrils, and larger aggregates. It is clear that polyQ length is a key determinant of htt aggregation and toxicity. However, the flanking sequences around polyQ domain, such as the first seventeen amino acids on the N terminus (Nt17), influence aggregation, aggregate stability, other important biochemical properties of the protein, and ultimately it role in pathogenesis. Here, we review the impact of Nt17 on both htt aggregation mechanisms and kinetics, structural properties of Nt17 in both monomeric and aggregate forms, the potential role of post translational modifications (PTMs) that occur in Nt17 in HD, and Nt17’s function as a membrane targeting domain.

Keywords: Huntington’s disease, huntingtin, polyglutamine, amyloid, lipid binding, post-translational modifications

Introduction

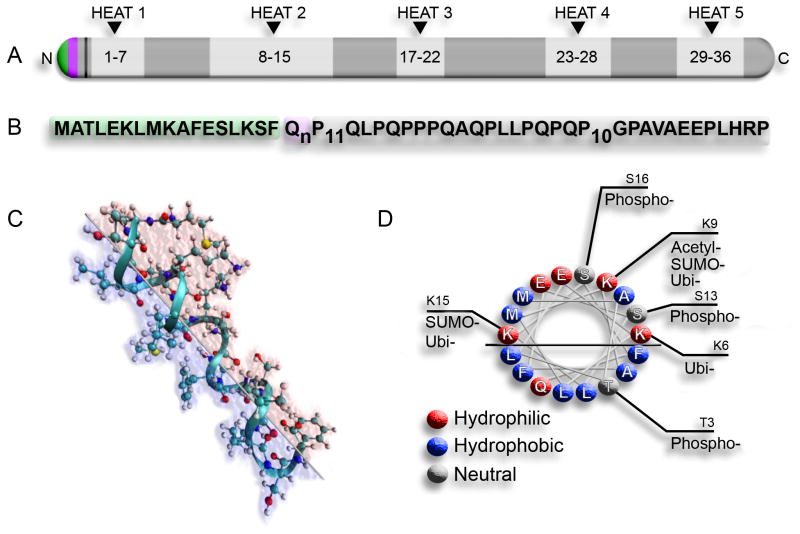

Huntington’s disease (HD), a fatal neurodegenerative disorder, is caused by an expansion of a polyglutamine (polyQ) tract near the N-terminus of the protein huntingtin (htt) (Figure 1) (1). This polyQ expansion directly leads to htt aggregation into fibrils and a variety of other aggregates (2–4). While the exact mass of htt is dependent on the size of the polyQ domain, full-length htt is approximately 350 kDa and is generally accepted to contain 3144 amino acids (Figure 1A). The polyQ domain begins at the 18th residue of htt and is contained in exon 1. Several lines of evidence suggested that N-terminal fragments comparable to exon 1 are directly involved in HD (5–10). The polyQ domain is flanked by the first 17 amino acids at the N-terminus (Nt17) of the protein and by a polyproline (polyp) stretch on its C-terminal side (Figure 1B). Downstream of exon 1 are a number of HEAT repeats that are 40-amino acid-long sequences that are involved in protein–protein interactions (11). Mutant htt is detected in patients’ brains predominantly as microscopic inclusion bodies in the cytoplasm and nucleus (8); however, htt is also associated with a variety of membranous organelles, including mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, tubulovesicles, endosomes, lysosomes and synaptic vesicles (12–16). The precise mechanisms by which htt aggregates are toxic to neural cells, leading to the extensive cellular destruction that is the hallmark of HD, remain unclear. As a result, there is a pressing need to understand structural factors that modulate htt aggregation, contribute to pathogenesis, and could potentially serve as therapeutic targets.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of various features of the htt protein.

A) Full length huntingtin protein with HEAT repeat sites (dark gray). The end of exon 1 is denoted by the black arrow. B) Primary sequence of htt exon 1 indicating Nt17 (green), polyQ (purple), and the proline-rich region (gray). C) Theoretical three dimensional structure of Nt17 indicating hydrophilic (red) and hydrophobic (blue) faces of an amphipathic α-helix. D) View down the barrel of the α-helix showing relative hydrophobicity of each residue (same color scheme as panel C), as well as the sites of reported post-translational modification.

There are currently nine diseases related to polyQ expansions in proteins that are broadly expressed, and the nature of the proteins that contain the polyQ domain and their associated pathologies differ substantially (17). That is, each mutant polyQ protein causes a distinct neurodegenerative disease that is associated with different populations of affected neurons. One of the key aspects of these diseases is that there is a threshold length of the polyQ domain required for disease with a tight correlation between both the age of onset and severity of disease with the increasing length of the polyQ expansion. Specifically for HD, polyQ repeat lengths shorter than 35 do not result in disease, 35–39 repeats may elicit disease, 40–60 repeats cause adult onset, and juvenile forms of HD are associated with repeats greater than 60 (18–20). This dependence and other observations suggest a toxic gain of function associated with expanded polyQ domains associated with these diseases.

While it is clear that polyQ expansion is central in HD, the context of the polyQ domain within htt can also play an important role. That is, the protein sequences directly adjacent to the polyQ domain can strongly influence the aggregation process both mechanistically and kinetically. This review focuses Nt17 domain and its potential role in HD. We will begin by reviewing the role of htt aggregation in HD from a general perspective and how Nt17 influences this specifically. Then, we will explore structural features of Nt17 that are of potential importance in HD. This will be followed by a discussion of the potential impact of post translational modifications (PTMs) that occur in Nt17. Finally, as Nt17 functions as a membrane targeting domain (14), we will end by discussing its role in htt aggregation on lipid membranes.

Microscopic inclusion bodies comprised of aggregated htt is a hallmark of HD

Over 40 years ago, abnormal nuclear structures were observed in HD brains (21); however, it was not until the development of the first mouse model of HD that it became apparent that these inclusions were composed of fibrillar aggregates of htt (8, 12). In these models, the expression of htt exon1 with an expanded polyQ tract was sufficient to cause a progressive neurological phenotype in transgenic mice. More recent studies demonstrated that N-terminal fragments similar to exon 1 are detected in knock-in mouse models of HD that express full length htt (9). While the major hallmark of HD is the formation of intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusion bodies of aggregated htt (22), the role of these intraneuronal aggregates in the etiology of HD remains controversial. For instance, in an early mouse models intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusion bodies preceded behavioral abnormalities (8); however, other studies indicate that inclusion body formation may protect against toxicity associated with soluble forms of htt by a sequestration mechanism (23–27).

Due to the direct correlation between htt aggregation and pathogenesis with polyQ length (28), it has been hypothesized that the aggregation of htt mediates neurodegeneration in HD. Due to the complexity of htt aggregation (as will be discussed in the next section), there is no clear consensus on the aggregate form(s) that underlie toxicity, and there likely exist bioactive oligomeric aggregates undetectable by traditional biochemical and electron microscopic approaches that precede symptoms. While identification of the toxic specie(s) of htt that trigger neurodegeneration in HD remains elusive, such species might exist in a diffuse, mobile fraction rather than in inclusion bodies (24). It has also been reported that a thioredoxin-polyQ fusion protein could exhibit toxicity in a meta-stable, β-sheet-rich monomeric conformation (29), suggesting that polyQ might adopt multiple monomeric conformations, only some of which may be toxic. Consistent with such a scenario, molecular dynamic simulations and circular dichroism spectropolarimetry (CD) indicate polyQ domains can adopt a heterogeneous collection of collapsed conformations that are in equilibrium prior to aggregation (30–33).

The complexity of polyQ-mediated aggregation in htt

It has been demonstrated, biochemically and biophysically, that htt fragments containing expanded polyQ tracts readily form detergent-insoluble protein aggregates with characteristics of amyloid fibrils (28, 34). Synthetic peptides comprised of expanded polyQ domains flanked by short sequences to provide solubility also aggregated into amyloid-like fibrils, confirming that polyQ aggregates into amyloid-like fibrils (30, 35). Furthermore, the rate of aggregation into fibrils is highly correlated with polyQ length in synthetic peptides and htt exon1 fragments (36). This correlation between aggregation rate and polyQ length has been recapitulated in cell culture models expressing htt fragments (27, 37, 38). While it is clear that htt with expanded polyQ tracts assemble into fibrils, htt also forms spherical and annular oligomeric structures (4, 39, 40). It is therefore evident that htt can form a variety of aggregate structures; however, the precise mechanisms by which these structures induce toxicity and neurodegeneration is unclear. Precise characterization of the possible aggregation pathways and the resulting heterogeneous mixtures of aggregates is a vital step in answering these important questions.

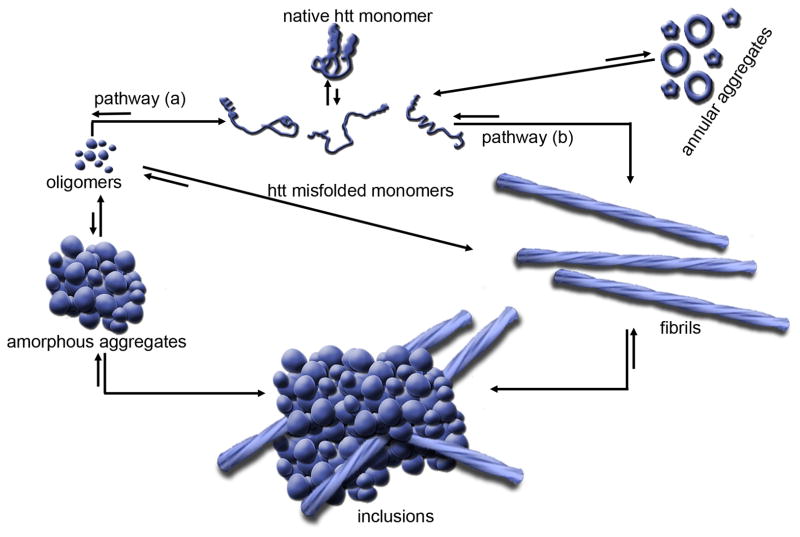

Extensive research has been performed to determine the kinetics of htt aggregation and to determine specific aggregate species on and off pathway to fibril formation (36). In this regard, several aggregation pathways have been proposed for the formation of fibrils of polyQ-containing proteins. Two of the more prominent aggregation schemes are: 1) re-arrangement of a monomer to a thermodynamically unfavorable conformation that directly nucleates fibril formation (41, 42) and 2) the formation of soluble oligomeric intermediates that slowly undergo structural re-arrangement into a β-sheet rich structure leading to fibrils (2, 43, 44) (Figure 2). The precise nature of the oligomeric aggregates associated with the second scheme can be quite heterogeneous (45, 46), and there could be a variety of oligomeric species that are off-pathway to fibril formation. While polyQ peptide fibrils share many classical features associated with amyloids, initial reports using pure polyQ peptides supported the nucleation-elongation model for the formation of polyQ fibrils (30, 35). Subsequent studies have suggested other potential mechanisms associated with the potential of smaller aggregates of polyQ proteins appearing prior to nucleation of fibril formation (43, 47). Small oligomers, displaying various degrees of stability, of polyQ peptides with various glutamine lengths were observed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) (2). Studies of polyQ peptides that were interrupted by other amino acids further support the formation of oligomers (44). While many oligomers were observed to directly initiate fibril formation when individually tracked in solution, many fibrils appeared to form without any obvious oligomeric precursors (2). Such observations suggest that these aggregation pathways are not mutually exclusive, making the situation considerably more complicated. Further AFM studies of a variety of htt-exon 1 fragments have shown that aggregation reactions result in heterogeneous mixtures of distinct aggregate morphologies in a polyQ length- and concentration-dependent manner (2). Novel oligomers of htt exon1 have also been identified in an in vitro mammalian system (45). Furthermore, distinct, polymorphic aggregates of htt have been observed (48), and x-ray crystallography has demonstrated that monomeric htt adopts multiple conformations (49, 50). These studies point to the complex nature of polyQ aggregation, necessitating the use of techniques capable of extracting quantitative data concerning relative amounts of specific aggregates forms.

Figure 2. A schematic model for htt aggregation.

A native monomer can sample a variety of distinct, misfolded monomer conformations, with the relative number and stability of these conformers potentially being polyQ length-dependent. Some misfolded monomers likely lead to aggregates, such as annular aggregates, that likely are off-pathway to fibril formation. There appears to be two generic aggregation pathways toward the formation of fibrils structures. (a) One of these pathways proceeds through oligomeric intermediates, some of which may be facilitated by Nt17. The size and stability of oligomeric aggregates can vary widely. A major structural transition must occur within an oligomer to initiate fibril elongation. (b)The other pathway to fibrils is a direct monomer to fibril transition. Oligomerization can also lead to the formation of large amorphous aggregates. All of these higher order aggregates may accumulate together to form the large inclusions that are a hallmark of HD.

Flanking sequences, including Nt17, play a prominent role in htt aggregation

It has been proposed that the protein composition surrounding expanded polyQ- domains associated with different diseases, and concomitant protein interactions that vary due to protein context, will help to explain, at least in part, the striking cell specificity that is observed in each disease. In fact, the impact of protein context on the aggregation of polyQ domains has been demonstrated in numerous studies and systems (51–57). Broadly, these studies suggest a potentially critical role of flanking sequences to polyQ structure and to potential mechanisms of aggregation. For example, the addition of a 10-residue polyP sequence to the C-terminus of a polyQ peptide, similar to that seen in htt, alter both aggregation kinetics and conformational properties of the polyQ tract (58). By inducing PPII-like helix structure that propagates into the polyQ domain, flanking polyP sequences also inhibit the formation of β-sheet structure in synthetic peptides, extending the length of the polyQ domain necessary to initiate fibril formation (59). The polyP domain interacts with vesicle trafficking proteins (i.e., HIP1, SH3GL3, and dynamin) in a manner that may function to sequester these proteins into htt inclusion bodies, leading to neuronal dysfunction (60). Furthermore, the polyP flanking sequence has proven to be an effective target for manipulating the aggregation pathway. The anti-htt antibody MW7, which is specific for the polyP region, suppresses aggregation of htt in vitro, promotes proteasomal turnover of htt, and reduces toxicity when expressed as a single chain variable fragment (scFv) in cellular models of HD (46, 61–63).

A potential mechanism by which Nt17 influences toxic htt aggregation is that the formation of abnormal aggregates of mutant htt is directly influenced by this domain. Indeed, Nt17 has been implicated in driving the initial phases of htt exon 1 interaction (14, 64–67). Several mechanisms have been proposed that are mediated by Nt17. Most agree that the initial phase of aggregation when Nt17 is present begins with self-association of this domain, resulting in the formation of small, α-helix rich oligomers (68–70). As such, it appears that Nt17 promotes fibril formation via the oligomer mediated pathway. In a cellular environment, pathogenic htt exon 1 oligomer populations do not appreciably change even with recruitment of monomers into inclusion bodies, suggesting that the formation of oligomeric species mediated by Nt17 is the rate-determining step (71, 72). Since oligomers are widely considered to be the toxic species in Huntington’s disease, the promotion of oligomerization by Nt17 could have potentially important consequences of htt-related toxicity. PolyQ peptides that do not have the N-terminal flanking sequence tend not to form oligomeric intermediates and as a result, proceed directly to fibrillar aggregates (69); although, some pure polyQ-peptide oligomers have been observed to form when aggregating on a surface (2, 73). The addition of a myc-tag preceding Nt17 in full htt exon 1 reduces the formation of oligomers in vitro without changing the rate of fibril formation when compared to exon 1 proteins of similar polyQ length that lacked this myc-tag (74), suggesting that the ability of Nt17 to promote oligomerization can be interfered with by steric hindrances. Such findings underscore the critical importance of protein context to the rate of aggregation, aggregate stability, protein-protein interactions, lipid-protein interactions, and cellular localization.

Nt17 structure in monomeric and aggregated htt

The Nt17 domain can form an amphipathic α-helix (AH) that is conserved in at least some aggregate forms of htt (Figure 1C) (66, 75, 76). There are several important biophysical properties associated with AHs (77), but in particular, AHs are often associated with binding of lipid membranes (78, 79). Briefly, an AH consists of a predominately hydrophilic face and a predominately hydrophobic face. AHs have been shown to have several functional properties such as preferentially sensing and binding highly curved membrane by detecting defects induced by curvature (80). Due to their ability to weakly bind membranes, their interaction with membranes is easily regulated. Nt17 has been shown to sequester truncated htt exon 1 peptides to regions of curvature on supported lipid bilayers (81). The structure of an AH is compatible with the formation of a variety of helix bundles in aqueous environment that is driven by maximizing the interaction of the hydrophobic faces of adjacent helices (82, 83). Due to this, the association of Nt17 via the formation of interacting AHs has been proposed to play a role in the initial stages of htt aggregation.

The Nt17 primary sequence contains three positively charged lysine residues at positions 6, 9, and 15 (Figure 1B). Residues 6 and 15 lie at the boundary between the hydrophilic and hydrophobic faces in a theoretical AH that extends the entire length of Nt17 (Figure 1C–D). Additionally, two methionine, two serine, and two glutamic acid residues also reside on the hydrophilic face. The hydrophobic face consists of two phenylalanine residues, three leucine residues, and an alanine residue, with a leucine and a phenylalanine at each side of the boundary. It would appear that residues in the boundary region are critical in lipid membrane binding and intermolecular interaction. Simulation of lipid membrane association show K6 and K15 are strong hydrogen bond donors with lipid bilayers (84). Similarly, K6 was found to be protected in an aggregated state by solution phase deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (85). These studies point to critical interactions involving amphipathic helices that can potentially be involved in the formation of the previously mentioned oligomeric precursors to fibril formation that are mediated by Nt17.

While there is little doubt that Nt17 is capable of forming an AH, under what conditions Nt17 adopts this structure in monomeric htt and the related consequences for aggregation are of critical importance. While the first crystal structures of htt exon 1 demonstrated that the polyQ domain is conformationally flexible, Nt17 was fully helical, with the helix extending into the polyQ domain for some crystal structures (50). Atomistic simulation in explicit aqueous solvent, CD, and solution NMR all point to transient helical properties of Nt17 in the monomer (67, 69, 86, 87). Separate analytical untracentrifugation (AUC) and CD studies further support that Nt17 is only transiently helical, and only forms the full, stable AH upon association with a binding partner (71). That is, predominately random coil monomeric Nt17 exists in solution in equilibrium with an α-helix rich tetrameric species that may act as a critical nucleus for amyloid formation. The AUC experiment showed the propensity for Nt17 to form tetramers, while concentration-dependent CD showed an increase in α-helicity for isolated Nt17 aggregates (71). Nt17 containing polyQ peptides that did not tetramerize are hypothesized to serve as a pool from which monomer addition can occur during fibril elongation. Computational predictions of Nt17’s free energy landscape in aqueous solution suggest that its most populated monomeric structure is a random coil that can interconvert, on a microsecond time-scale, with several helical conformers (86). Other atomistic simulations suggest that Nt17 exists in a two-helix bundle at 300K and transiently exists as a straight helix (67).

Compelling evidence demonstrate that the α-helix is conserved in fibrils (66, 85, 88). Solid state NMR and FTIR studies confirm that the α-helix is conserved upon aggregation with polyQ segments above n = 30 (66). A strong IR absorbance at 1655 cm−1, indicative of α-helical character, from both small aggregates of Nt17 as well as htt exon 1 model peptides was observed in FTIR experiments. Additionally, ssNMR chemical shifts and precise intrapeptide NOE measurements indicate residues 4 – 11 are in an α-helical arrangement within a fibril structure, while residues 17 – 19 have a clear β-sheet structure (66). The location of Nt17 within fibrils appears to be on the periphery of the amyloid structure, as shown by ssNMR (66) and mass spectrometry (MS) (85); however, pre-aggregated htt exon 1 inefficiently binds to lipid membranes, suggesting Nt17 is tightly bound, or otherwise unavailable, in the final amyloid structure (89). The unavailability of Nt17 may be due to it being highly ordered in the fibril structure, as was observed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (88). Analysis of these EPR results suggested that Nt17 could potentially make up the core of some fibrils. However, Nt17 appeared to undergo specific solvent-coupled motions in mature fibrils, as demonstrated by quantitative ssNMR measurements of residue-specific dynamics (90). Such solvent exposure and structural flexibility could allow for Nt17 to facilitate the interaction of htt aggregates with their environment. Such discrepancies in the location of Nt17 could suggest the formation polymorphic fibrils structures under different experimental systems and conditions (91). Still, these studies provide substantial evidence for the helical nature of Nt17 within amyloid fibrils.

The importance of Nt17 as a potential therapeutic target

Since Nt17 has been implicated in the formation of the toxic intermediate, it represents a novel structural target to inhibit (or alter) aggregate formation, thereby hopefully alleviating htt-mediated toxicity. A potential strategy would be targeted removal of the Nt17 tract all together; a concept that has been explored in vitro by cleaving Nt17 via proteolysis (42, 71). A tryptic proteolytic fragment of Nt17Q37P10K2 (SFQ37P10K2) exhibited aggregation kinetics and morphologies similar to K2Q37K2, a simple polyQ peptide that lacks both flanking sequences (42). Similarly, a MFQ37P10K2 tryptic analogue was shown to have similar kinetics to the true tryptic fragment (91). In vitro, these studies are a simple means of studying Nt17-mediated aggregation, but do not represent a likely means of treatment in vivo, due to the difficulty of selective proteolysis.

Perhaps a more practical means of inhibiting N-terminal aggregation is through structural complexation, either by a chaperone or an antibody-antigen that interacts directly with this domain (92–97). Interestingly, free Nt17 (lacking any polyQ) has been used to inhibit Nt17-mediated formation of Nt17Q37P10K2 peptides in vitro (76, 91). The mechanism by which Nt17 inhibits amyloid formation appears to be identical to the mechanism by which nucleation occurs, with the caveat that Nt17 alone does not contain an amyloidogenic polyQ tract. This increases the distance between adjacent polyQ tracts and the energy for polyQ fibrillization to occur (76). It has also been known for some time that molecular chaperones can modulate htt aggregation (98, 99). Many of these molecular chaperones, including Hsc70 (100) and Tric (94, 95), have been shown to bind directly to Nt17.

Another potential therapeutic strategy that has been extensively studied is the use of antibodies; unlike peptide therapeutics and inhibitors, antibodies are specific only for the target antigen. Several antibodies exist for htt exon 1, each recognizing distinct domains and potentially distinct monomers or aggregates (46, 101–104). In the past decade, intracellular antibodies, or intrabodies, for Nt17 have been developed that inhibit htt exon 1 fibrillization and cytotoxicity in vitro and cellular huntingtin model, two of which are scFv and VL 12.3.(92, 93, 105). When co-transfected with htt exon 1 (104Q) into COS-7, BHK-21, and HEK-293 cells, C4 scFv was shown to decrease aggregate formation relative to control groups that were not transfected with the intrabody (105). C4 scFv bound to htt exon 1 structures of non-pathogenic length (25Q), as well, which indicates the polyQ conformation does not play a role in intrabody binding, and that the most likely binding target is Nt17 (105). The second intrabody, VL 12.3, also targets the Nt17 domain; however, unlike C4, VL 12.3 consists of only a single chain of the typical antibody structure. The efficacy of this antibody is highly increased after removal of disulfide bonds within the antibody structure (92, 93). Interestingly, an X-ray crystal structure of the antibody-antigen complex revealed that Nt17 was helical in the binding pocket of the intrabody (92), which either suggests the binding pocket induces helicity in the proposed random structure of Nt17, or the intrabody only recognizes helical Nt17. Intrabodies that were co-expressed with a pathogenic GFP-fused htt exon 1 (97 Q) in HEK293 mammalian cells caused a dramatic decrease in huntingtin inclusion bodies relative to controls. The VL 12.3 intrabody was at least as effective in retarding aggregate formation as the C4 intrabody (92), as shown by fluorescence immunomicroscopy. These studies show that structural inhibition of Nt17 is certainly a viable means of inhibiting aggregation and, potentially, htt exon 1 toxicity.

Post translational modifications in Nt17

Nt17 also contains numerous sites that can be post-translationally modified, with some sites associated with multiple potential modifications (Figure 1D) (106–108). These post translational modification (PTMs) appear to have a profound effect on htt function and translocation (109–111), as well as toxicity associated with htt containing expanded polyQ domains (106, 107, 112–114). Most prevalent forms of PTMs occurring in Nt17 are phosphorylation (65, 114–117), acetylation (118), ubiquitination (119), SUMOylation (106, 112), and removal of the N-terminal methionine (114). Other htt modifications such as palmitoylation (120) and transglutamination (121) have also been observed.

The htt Nt17 domain has three potential phosphorylatable sites: threonine 3, (T3), serine 13 (S13), and serine (S16) (full length htt can also be phosphorylated at serine residues downstream from the N terminal domain. Numerous studies have reported that htt phosphorylation is associated with reduced levels of mutant htt toxicity (108, 114, 116, 117, 122–124). Mutating T3 to aspartate to mimic phosphorylation enhances the propensity of htt to aggregate in cultured cells and resulted in reduced lethality and neurodegeneration in Drosophila models of HD (114). Htt containing phospho-serine residues at 13 and 16 aggregate in a similar fashion to serine to aspartate phosphomimetic mutations, demonstrating that serine phosphometic mutations are valid mimics for studying the impact of htt phosphorylation on aggregation. Using a variety of combinations of serine phosphorylation mimics, it was established that serine to aspartate mutations significantly slows the formation htt aggregates and reduces the stability of the fibril structure (65, 117). When S13 and S16 were mutated to aspartate in the Nt17 domain of transgenic mice that expresses full length htt with 97Q, visible htt inclusions within the brain were reduced, and HD–like behavioral phenotypes were reduced at 12 months of age (117). Altering the phosphorylation state of htt (specifically at S13) indirectly can also impact expanded htt related toxicity, as casein kinase 2 inhibitors reduced S13 phosphorylation with a subsequent enhancement of htt-related toxicity in high content live cell screenings (125). Furthermore, ganglioside, GM1, triggers htt phosphorylation at S13 and S16, diminishing htt toxicity while restoring normal motor behavior in transgenic mice (115). Collectively, these finding further support the notion that Nt17 plays an important role in htt aggregation and, more specifically, that altering the phosphorylation state of Nt17 may be a viable therapeutic strategy.

Htt can also undergo SUMOylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation on specific lysine residues within Nt17. These potential sites include lysine residues at position 6, 9, and 15. SUMOylation, specifically, has been implicated in both cell and animal models to be involved in HD pathogenesis (106, 112). SUMOylation at lysine 6 (K6) and lysine 9 (K9) stabilizes htt exon1 fragments, reducing aggregation in cultured cells and exacerbating toxicity in Drosophila HD models (106). Rhes, a small G protein, preferentially binds mutant htt over wild type and acts as a SUMO E3 ligase (126). The subsequent SUMOylation by Rhes increases soluble levels of htt and enhances neurotoxicity (126). Ubiquitination is known to compete for the same lysine residues as SUMOylation, but functionally, it is associated with tagging proteins for degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS), thereby reducing the toxicity of the mutant htt (127). However, the presence of ubiquitin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions in the HD striatum and cortex shows that the detoxification mechanisms by ubiquitination is incomplete for most proteins (12). Proteomic mapping by MS verified within Nt17 that K9 is appreciably acetylated in mammalian cell lysates (128). While the role of K9 acetylation has not yet been fully evaluated, acetylation of lysine 444 (K444) has been implicated in autophagic removal of mutant htt for clearance leading to neuroprotection in C. elegans HD model (118). Perhaps, acetylation within Nt17 plays a similar role, but the impact of acetylation within Nt17 on aggregation and toxicity of htt has not been fully elucidated.

Finally, PTMs can occur in tandem, directly affecting other PTMs. For instance, htt SUMOylation can be modulated by phosphorylation, explaining why S13 and S16 phosphomimics in htt were found to modulate SUMO-1 modification both in cells and in vivo (116, 117). SUMOylation is a transient process, and Nt17 lysines are predicted as low probability SUMO sites. Therefore, one way to enhance Nt17 SUMO-1 modification is to use serine phosphomimetic mutants (112). Interestingly, these phosphomimics also promote K6 htt SUMOylation, which may represent one way to regulate K9 acetylation (112). SUMOylation and ubiquitination can also influence each other by competing for the same Nt17 lysine 6, 9 and 15 (106), implying that one modification could be used to control or enhance the other. Understanding how Nt17 PTMs impact htt and modulate each other could lead to therapeutic intervention with the potential implications to HD.

Nt17 mediates htt/lipid interactions with potential implications for toxicity

Another potential role of Nt17 in htt-related toxicity is that Nt17 directly dictates whether, and to what extent, toxic protein aggregates interact with cellular and subcellular compartments, such as organelles. These interactions would be mediated by Nt17’s ability to bind membranes comprised predominately of lipids and could play an important role in htt trafficking. These membranes may also be direct targets of htt aggregates, that is, htt aggregates may alter membrane structure and stability as part of a molecular mechanism of toxicity. A considerable number of observations directly and indirectly support such notions. Htt has been implicated in the transport of lipid vesicles (endocytic, synaptic or lysosomal), especially along microtubules (129–132). Expanded polyQ-conferred nuclear localization of htt appears to require additional htt sequences such as Nt17 (133), and Nt17 itself has been implicated to function as a nuclear export signal (134). Htt also associates with acidic phospholipids (135) which could play a role in nucleating aggregation. Furthermore, htt localizes to brain membrane fractions (136) which are primarily comprised of lipids.

There are a variety of membrane-associated functions attributable to htt in which the lipid-binding properties of Nt17 may play a role. These functions include cellular adhesion (137), motility (138, 139), cholesterol and energy homeostasis (140), and as a molecular scaffold for coordination of membrane and cytoskeletal communication (135) as well as facilitating micrutobule-dependent vesicle transport (141). Nt17 facilitates the trafficking of htt exon 1 to membranes associated with the ER, autophagic vacuoles, mitochondria, and Golgi (14, 142). Membrane curvature sensing, facilitated by AH structural characteristics of Nt17, may play a mechanistic role in these functions (81). Additional evidence that Nt17 directly interacts with lipid membranes was provided by the observation that the binding of htt exon 1 to large unilamellar vesicles composed of phosphatidylcholines (PC) or a mixture of PC and phosphatidylserines (PS) enhanced the helical content of Nt17 (14). These changes in helical content were blocked by changing the eighth residue of Nt17 to a proline (14). A structural transition from random-coil in solution to an α-helical structure upon binding lipid bilayers was validated by high-resolution ssNMR structural studies (143, 144). Nt17 in synthetic polyQ peptides was required for synthetic polyQ peptides to bind model brain lipid extract membranes (73). Synthetic polyQ peptides with a variety of flanking sequences readily form fibrils in solution or solid surfaces such as mica, but lipid membranes stabilize discrete oligomeric aggregates of polyQ peptides that contain Nt17 (73). However, both Nt17 and a C-terminal polyP domain were required for polyQ peptides to destabilize membrane structure, leading to leakage. Computational studies further support the important role of Nt17 in htt/lipid interactions and also provide evidence that the presence of both Nt17 and polyP enhance the interaction of htt with bilayers (84). The cooperative effect of Nt17 and the polyP domain in disrupting membranes may be particularly important in light of observed interactions between these two domains in a cellular environment that is altered with increasing polyQ length (145). The binding and disruption of lipid membranes by full htt exon 1 constructs can be partially inhibited by the addition of N-terminal tags, further supporting a prominent role of Nt17 in these phenomena (89).

In terms of a potential role in htt-related toxic mechanisms, the accumulation of monomeric htt and/or prefibrillar aggregates directly binding lipid membranes has been shown to disrupt bilayer integrity and to induce mechanical changes in the membrane (89, 146). Another factor regulating the interaction of htt with lipid membranes mediated by Nt17 are the previously discussed PTMs, which are known to be involved in htt translocating to specific organelles (14, 147). Additional affinity-based components for the interaction of other AHs with lipid bilayers also play a role, including electrostatics (148, 149), partitioning of lipid components (150–152), or the presence of other specific recognition motifs (153, 154). The availability of Nt17 to interact with lipid membranes could also play an important role in cell to cell transport of htt aggregates. This may prove particularly important with the realization that there are non-cell-autonomous toxic effects associated with HD (155–159).

Expert Opinion

The collective evidence reviewed here strongly supports the conclusion that there is a need to identify at a mechanistic level the precise role Nt17 may play in modulating the formation of toxic aggregates, as well as influencing interactions with subcellular surfaces. Future studies aimed at further elucidating the role of Nt17 in the formation and stabilization of relevant aggregate species and potential toxic mechanisms involved in HD may prove particularly useful. Such information is important because it could lead to better defined therapeutic targets and strategies to treat HD in addition to the polyQ tract.

Highlights.

Due to the complexity of htt aggregation and diversity of potential aggregate forms, there is no clear consensus on the underlying toxic specie(s) most relevant to HD; however, there likely exists a variety of bioactive aggregates ranging from oligomers to fibrils.

Precise characterization of htt aggregation and resulting aggregate structure may prove vital, and such studies will require the use of a variety of biochemical and biophysical techniques.

Several studies have suggested a critical role of the Nt17 domain in htt in modifying the rate of aggregation, relative aggregate stability, specific protein-protein interactions, lipid-protein interactions, and cellular localization.

A potential mechanism by which Nt17 influences toxic htt aggregation is by promoting the formation of oligomeric aggregates of htt.

PTMs occurring in Nt17 can have a profound effect on htt function and translocation, as well as modifying the toxic gain of function associated with mutant htt.

Targeting Nt17 through a variety of strategies, i.e. antibodies, small peptides, PTMs, can effectively inhibit or alter aggregation of mutant htt, suggesting that such strategies may represent viable therapeutic strategies.

Nt17 directly dictates whether, and to what extent, htt interacts with cellular and subcellular membranes, and htt aggregation may alter membrane structure and stability as part of a variety of molecular mechanism associated with toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R15NS090380. MC and JRA were supported by the WV Higher Education Policy Commission/Division of Science and Research.

Abbreviations

- AH

amphipathic α-helix

- AUC

analytical untracentrifugation

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

- CD

circular dichroism spectropolarimetry

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- Htt

huningtin protein

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NOE

Nuclear Overhauser Effect

- PC

phosphatidylcholines

- PS

phosphatidylserines

- polyQ

polyglutamine

- polyP

polyproline

- PTMs

post translational modifications

- scFv

single chain variable fragment

- ssNMR

solid state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

References

- 1.The Collaborative Huntington’s Disease Research Group. A Novel Gene Containing a Trinucleotide Repeat That Is Expanded and Unstable on Huntington’s Disease Chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Legleiter J, Mitchell E, Lotz GP, Sapp E, Ng C, DiFiglia M, Thompson LM, Muchowski PJ. Mutant Huntingtin Fragments Form Oligomers in a Polyglutamine Length-dependent Manner in Vitro and in Vivo. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14777–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vonsattel JP, Myers RH, Stevens TJ, Ferrante RJ, Bird ED, Richardson EP. Neuropathologoical Classification of Huntingtons Disease. J Neuropath Exp Neur. 1985;44:559–77. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poirier MA, Li HL, Macosko J, Cai SW, Amzel M, Ross CA. Huntingtin spheroids and protofibrils as precursors in polyglutamine fibrilization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41032–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YJ, Yi Y, Sapp E, Wang Y, Cuiffo B, Kegel KB, Qin Z-H, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Caspase 3-cleaved N-terminal fragments of wild-type and mutant huntingtin are present in normal and Huntington’s disease brains, associate with membranes, and undergo calpain-dependent proteolysis. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12784–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221451398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper JK, Schilling G, Peters MF, Herring WJ, Sharp AH, Kaminsky Z, Masone J, Khan FA, Delanoy M, Borchelt DR, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ross CA. Truncated N-Terminal Fragments of Huntingtin with Expanded Glutamine Repeats form Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Aggregates in Cell Culture. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:783–90. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.5.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffner G, Island M-L, Djian P. Purification of neuronal inclusions of patients with Huntington’s disease reveals a broad range of N-terminal fragments of expanded huntingtin and insoluble polymers. J Neurochem. 2005;95:125–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies SW, Turmaine M, Cozens BA, DiFiglia M, Sharp AH, Ross CA, Scherzinger E, Wanker EE, Mangiarini L, Bates GP. Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation. Cell. 1997;90:537–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landles C, Sathasivam K, Weiss A, Woodman B, Moffitt H, Finkbeiner S, Sun B, Gafni J, Ellerby LM, Trottier Y, Richards WG, Osmand A, Paganetti P, Bates GP. Proteolysis of Mutant Huntingtin Produces an Exon 1 Fragment That Accumulates as an Aggregated Protein in Neuronal Nuclei in Huntington Disease. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8808–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.075028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sathasivam K, Neueder A, Gipson TA, Landles C, Benjamin AC, Bondulich MK, Smith DL, Faull RLM, Roos RAC, Howland D, Detloff PJ, Housman DE, Bates GP. Aberrant splicing of HTT generates the pathogenic exon 1 protein in Huntington disease. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2366–70. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221891110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neuwald AF, Hirano T. HEAT Repeats Associated with Condensins, Cohesins, and Other Complexes Involved in Chromosome-Related Functions. Genome Res. 2000;10:1445–52. doi: 10.1101/gr.147400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, Davies SW, Bates GP, Vonsattel JP, Aronin N. Aggregation of Huntingtin in Neuronal Intranuclear Inclusions and Dystrophic Neurites in Brain. Science. 1997;277:1990–3. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutekunst CA, Li SH, Yi H, Mulroy JS, Kuemmerle S, Jones R, Rye D, Ferrante RJ, Hersch SM, Li XJ. Nuclear and neuropil aggregates in Huntington’s disease: Relationship to neuropathology. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2522–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-07-02522.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atwal RS, Xia J, Pinchev D, Taylor J, Epand RM, Truant R. Huntingtin has a membrane association signal that can modulate huntingtin aggregation, nuclear entry and toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2600–15. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kegel-Gleason KB. Huntingtin Interactions with Membrane Phospholipids: Strategic Targets for Therapeutic Intervention? J Huntington’s Dis. 2013;2:239–50. doi: 10.3233/JHD-130068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leitman J, Ulrich Hartl F, Lederkremer GZ. Soluble forms of polyQ-expanded huntingtin rather than large aggregates cause endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Commun. 2013;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber JJ, Sowa AS, Binder T, Hübener J. From Pathways to Targets: Understanding the Mechanisms behind Polyglutamine Disease. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:22. doi: 10.1155/2014/701758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Penney JB, Vonsattel JP, MacDonald ME, Gusella JF, Myers RH. CAG repeat number governs the development rate of pathology in Huntington’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:689–92. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snell RG, Macmillan JC, Cheadle JP, Fenton I, Lazarou LP, Davies P, Macdonald ME, Gusella JF, Harper PS, Shaw DJ. Relationship between trinucleotide repeat expansion and phenotypic variation in Huntingtons disease. Nat Genet. 1993;4:393–7. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobin AJ, Signer ER. Huntington’s disease: the challenge for cell biologists. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:531–6. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)01853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roizin L, Stellar S, Willson N, Whittier J, Liu JC. Electron microscope and enzyme studies in cerebral biopsies of Huntington’s chorea. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1974;99:240–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zoghbi HY, Orr HT. Glutamine repeats and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:217–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arrasate M, Finkbeiner S. Protein aggregates in Huntington’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2012;238:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431:805–10. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J, Arrasate M, Brooks E, Libeu CP, Legleiter J, Hatters D, Curtis J, Cheung K, Krishnan P, Mitra S, Widjaja K, Shaby BA, Lotz GP, Newhouse Y, Mitchell EJ, Osmand A, Gray M, Thulasiramin V, Saudou F, Segal M, Yang XW, Masliah E, Thompson LM, Muchowski PJ, Weisgraber KH, Finkbeiner S. Identifying polyglutamine protein species in situ that best predict neurodegeneration. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:925–34. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muchowski PJ, Ning K, D’Souza-Schorey C, Fields S. Requirement of an intact microtubule cytoskeleton for aggregation and inclusion body formation by a mutant huntingtin fragment. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:727–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022628699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saudou F, Finkbeiner S, Devys D, Greenberg ME. Huntingtin acts in the nucleus to induce apoptosis but death does not correlate with the formation of intranuclear inclusions. Cell. 1998;95:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scherzinger E, Lurz R, Turmaine M, Mangiarini L, Hollenbach B, Hasenbank R, Bates GP, Davies SW, Lehrach H, Wanker EE. Huntingtin-encoded polyglutamine expansions form amyloid-like protein aggregates in vitro and in vivo. Cell. 1997;90:549–58. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80514-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagai Y, Inui T, Popiel HA, Fujikake N, Hasegawa K, Urade Y, Goto Y, Naiki H, Toda T. A toxic monomeric conformer of the polyglutamine protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:332–40. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen S, Berthelier V, Yang W, Wetzel R. Polyglutamine aggregation behavior in vitro supports a recruitment mechanism of cytotoxicity. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:173–82. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vitalis A, Wang X, Pappu RV. Quantitative characterization of intrinsic disorder in polyglutamine: Insights from analysis based on polymer theories. Biophys J. 2007;93:1923–37. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.110080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vitalis A, Wang X, Pappu RV. Atomistic Simulations of the Effects of Polyglutamine Chain Length and Solvent Quality on Conformational Equilibria and Spontaneous Homodimerization. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:279–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang XL, Vitalis A, Wyczalkowski MA, Pappu RV. Characterizing the conformational ensemble of monomeric polyglutamine. Proteins. 2006;63:297–311. doi: 10.1002/prot.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scherzinger E, Sittler A, Schweiger K, Heiser V, Lurz R, Hasenbank R, Bates GP, Lehrach H, Wanker EE. Self-assembly of polyglutamine-containing huntingtin fragments into amyloid-like fibrils: Implications for Huntington’s disease pathology. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen SM, Berthelier V, Hamilton JB, O’Nuallain B, Wetzel R. Amyloid-like features of polyglutamine aggregates and their assembly kinetics. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7391–9. doi: 10.1021/bi011772q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wetzel R. Physical Chemistry of Polyglutamine: Intriguing Tales of a Monotonous Sequence. J Mol Biol. 2012;421:466–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lunkes A, Mandel JL. A cellular model that recapitulates major pathogenic steps of Huntington’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1355–61. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hackam AS, Singaraja R, Wellington CL, Metzler M, McCutcheon K, Zhang TQ, Kalchman M, Hayden MR. The influence of Huntingtin protein size on nuclear localization and cellular toxicity. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1097–105. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka M, Morishima I, Akagi T, Hashikawa T, Nukina N. Intra- and intermolecular beta-pleated sheet formation in glutamine-repeat inserted myoglobin as a model for polyglutamine diseases. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45470–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107502200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wacker JL, Zareie MH, Fong H, Sarikaya M, Muchowski PJ. Hsp70 and Hsp40 attenuate formation of spherical and annular polyglutamine oligomers by partitioning monomer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:1215–22. doi: 10.1038/nsmb860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen SM, Ferrone FA, Wetzel R. Huntington’s disease age-of-onset linked to polyglutamine aggregation nucleation. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11884–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182276099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kar K, Jayaraman M, Sahoo B, Kodali R, Wetzel R. Critical nucleus size for disease-related polyglutamine aggregation is repeat-length dependent. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:328. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walters RH, Murphy RM. Examining Polyglutamine Peptide Length: A Connection between Collapsed Conformations and Increased Aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2009;393:978–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walters RH, Murphy RM. Aggregation Kinetics of Interrupted Polyglutamine Peptides. J Mol Biol. 2011;412:505–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nucifora LG, Burke KA, Feng X, Arbez N, Zhu SS, Miller J, Yang GC, Ratovitski T, Delannoy M, Muchowski PJ, Finkbeiner S, Legleiter J, Ross CA, Poirier MA. Identification of Novel Potentially Toxic Oligomers Formed in Vitro from Mammalian-derived Expanded huntingtin Exon-1 Protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:16017–28. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.252577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Legleiter J, Lotz GP, Miller J, Ko J, Ng C, Williams GL, Finkbeiner S, Patterson PH, Muchowski PJ. Monoclonal Antibodies Recognize Distinct Conformational Epitopes Formed by Polyglutamine in a Mutant Huntingtin Fragment. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21647–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bernacki JP, Murphy RM. Model Discrimination and Mechanistic Interpretation of Kinetic Data in Protein Aggregation Studies. Biophys J. 2009;96:2871–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nekooki-Machida Y, Kurosawab M, Nukina N, Ito K, Oda T, Tanaka M. Distinct conformations of in vitro and in vivo amyloids of huntingtin-exon1 show different cytotoxicity. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:9679–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812083106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim M. Beta conformation of polyglutamine track revealed by a crystal structure of Huntingtin N-terminal region with insertion of three histidine residues. Prion. 2013;7:221–8. doi: 10.4161/pri.23807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim MW, Chelliah Y, Kim SW, Otwinowski Z, Bezprozvanny I. Secondary Structure of Huntingtin Amino-Terminal Region. Structure. 2009;17:1205–12. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bulone D, Masino L, Thomas DJ, Biagio PLS, Pastore A. The Interplay between PolyQ and Protein Context Delays Aggregation by Forming a Reservoir of Protofibrils. PLoS One. 2006;1:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duennwald ML, Jagadish S, Giorgini F, Muchowski PJ, Lindquist S. A network of protein interactions determines polyglutamine toxicity. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11051–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604548103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duennwald ML, Jagadish S, Muchowski PJ, Lindquist S. Flanking sequences profoundly alter polyglutamine toxicity in yeast. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11045–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604547103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ignatova Z, Gierasch LM. Extended polyglutamine tracts cause aggregation and structural perturbation of an adjacent beta barrel protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12959–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.La Spada AR, Taylor JP. Polyglutamines placed into context. Neuron. 2003;38:681–4. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Menon RP, Pastore A. Expansion of amino acid homo-sequences in proteins: Insights into the role of amino acid homo-polymers and of the protein context in aggregation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:1677–85. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6097-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nozaki K, Onodera O, Takano H, Tsuji S. Amino acid sequences flanking polyglutamine stretches influence their potential for aggregate formation. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3357–64. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200110290-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bhattacharyya A, Thakur AK, Chellgren VM, Thiagarajan G, Williams AD, Chellgren BW, Creamer TP, Wetzel R. Oligoproline effects on polyglutamine conformation and aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2006;355:524–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darnell G, Orgel JPRO, Pahl R, Meredith SC. Flanking polyproline sequences inhibit beta-sheet structure in polyglutamine segments by inducing PPII-like helix structure. J Mol Biol. 2007;374:688–704. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qin ZH, Wang YM, Sapp E, Cuiffo B, Wanker E, Hayden MR, Kegel KB, Aronin N, DiFiglia M. Huntingtin bodies sequester vesicle-associated proteins by a polyproline-dependent interaction. J Neurosci. 2004;24:269–81. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1409-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khoshnan A, Ko J, Patterson PH. Effects of intracellular expression of anti-huntingtin antibodies of various specificities on mutant huntingtin aggregation and toxicity. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1002–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022631799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Southwell AL, Khoshnan A, Dunn DE, Bugg CW, Lo DC, Patterson PH. Intrabodies binding the proline-rich domains of mutant huntingtin increase its turnover and reduce neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9013–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2747-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Southwell AL, Ko J, Patterson PH. Intrabody Gene Therapy Ameliorates Motor, Cognitive, and Neuropathological Symptoms in Multiple Mouse Models of Huntington’s Disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:13589–602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4286-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crick SL, Ruff KM, Garai K, Frieden C, Pappu RV. Unmasking the roles of N- and C-terminal flanking sequences from exon 1 of huntingtin as modulators of polyglutamine aggregation. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320626110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mishra R, Hoop CL, Kodali R, Sahoo B, van der Wel PCA, Wetzel R. Serine Phosphorylation Suppresses Huntingtin Amyloid Accumulation by Altering Protein Aggregation Properties. J Mol Biol. 2012;424:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sivanandam VN, Jayaraman M, Hoop CL, Kodali R, Wetzel R, van der Wel PCA. The Aggregation-Enhancing Huntingtin N-Terminus Is Helical in Amyloid Fibrils. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4558–66. doi: 10.1021/ja110715f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelley NW, Huang X, Tam S, Spiess C, Frydman J, Pande VS. The Predicted Structure of the Headpiece of the Huntingtin Protein and Its Implications on Huntingtin Aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:919–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williamson TE, Vitalis A, Crick SL, Pappu RV. Modulation of Polyglutamine Conformations and Dimer Formation by the N-Terminus of Huntingtin. J Mol Biol. 2010;396:1295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thakur AK, Jayaraman M, Mishra R, Thakur M, Chellgren VM, Byeon IJL, Anjum DH, Kodali R, Creamer TP, Conway JF, Gronenborn AM, Wetzel R. Polyglutamine disruption of the huntingtin exon 1 N terminus triggers a complex aggregation mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:380–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vitalis A, Pappu RV. Assessing the contribution of heterogeneous distributions of oligomers to aggregation mechanisms of polyglutamine peptides. Biophys Chem. 2011;159:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jayaraman M, Kodali R, Sahoo B, Thakur AK, Mayasundari A, Mishra R, Peterson CB, Wetzel R. Slow Amyloid Nucleation via alpha-Helix-Rich Oligomeric Intermediates in Short Polyglutamine-Containing Huntingtin Fragments. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:881–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olshina MA, Angley LM, Ramdzan YM, Tang JW, Bailey MF, Hill AF, Hatters DM. Tracking Mutant Huntingtin Aggregation Kinetics in Cells Reveals Three Major Populations That Include an Invariant Oligomer Pool. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21807–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.084434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burke KA, Kauffman KJ, Umbaugh CS, Frey SL, Legleiter J. The Interaction of Polyglutamine Peptides With Lipid Membranes is Regulated by Flanking Sequences Associated with Huntingtin. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.446237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burke KA, Godbey J, Legleiter J. Assessing mutant huntingtin fragment and polyglutamine aggregation by atomic force microscopy. Methods. 2011;53:275–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sahoo B, Singer D, Kodali R, Zuchner T, Wetzel R. Aggregation Behavior of Chemically Synthesized, Full-Length Huntingtin Exon1. Biochemistry. 2014;53:3897–907. doi: 10.1021/bi500300c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mishra R, Jayaraman M, Roland BP, Landrum E, Fullam T, Kodali R, et al. Inhibiting the Nucleation of Amyloid Structure in a Huntingtin Fragment by Targeting alpha-Helix-Rich Oligomeric Intermediates. J Mol Biol. 415:900–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Drin G, Antonny B. Amphipathic helices and membrane curvature. FEBS Letters. 2010;584:1840–7. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brass V, Bieck E, Montserret R, Wölk B, Hellings JA, Blum HE, Penin F, Moradpour D. An Amino-terminal Amphipathic α-Helix Mediates Membrane Association of the Hepatitis C Virus Nonstructural Protein 5A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8130–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Georgieva Elka R, Xiao S, Borbat Peter P, Freed Jack H, Eliezer D. Tau Binds to Lipid Membrane Surfaces via Short Amphipathic Helices Located in Its Microtubule-Binding Repeats. Biophys J. 2014;107:1441–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cui H, Lyman E, Voth GA. Mechanism of Membrane Curvature Sensing by Amphipathic Helix Containing Proteins. Biophys J. 2011;100:1271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chaibva M, Burke KA, Legleiter J. Curvature Enhances Binding and Aggregation of Huntingtin at Lipid Membranes. Biochemistry. 2014;53:2355–65. doi: 10.1021/bi401619q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gouttenoire J, Roingeard P, Penin F, Moradpour D. Amphipathic α-helix AH2 is a major determinant for the oligomerization of hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 4B. J Virol. 2010;84:12529–37. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01798-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Westerlund JA, Weisgraber KH. Discrete carboxyl-terminal segments of apolipoprotein E mediate lipoprotein association and protein oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15745–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nagarajan A, Jawahery S, Matysiak S. The Effects of Flanking Sequences in the Interaction of Polyglutamine Peptides with a Membrane Bilayer. J Phys Chem B. 2013 doi: 10.1021/jp407900c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arndt JR, Brown RJ, Burke KA, Legleiter J, Valentine SJ. Lysine Residues in the N-Terminal Huntingtin Amphipathic α-Helix Play a Key Role in Peptide Aggregation. J Mass Spectrom. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jms.3504. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rossetti G, Cossio P, Laio A, Carloni P. Conformations of the Huntingtin N-term in aqueous solution from atomistic simulations. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:3086–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dlugosz M, Trylska J. Secondary Structures of Native and Pathogenic Huntingtin N-Terminal Fragments. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:11597–608. doi: 10.1021/jp206373g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bugg CW, Isas JM, Fischer T, Patterson PH, Langen R. Structural Features and Domain Organization of Huntingtin Fibrils. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:31739–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.353839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Burke KA, Hensal KM, Umbaugh CS, Chaibva M, Legleiter J. Huntingtin disrupts lipid bilayers in a polyQ-length dependent manner. BBA-Biomembranes. 2013;1828:1953–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hoop CL, Lin H-K, Kar K, Hou Z, Poirier MA, Wetzel R, van der Wel PCA. Polyglutamine Amyloid Core Boundaries and Flanking Domain Dynamics in Huntingtin Fragment Fibrils Determined by Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Biochemistry. 2014;53:6653–66. doi: 10.1021/bi501010q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jayaraman M, Mishra R, Kodali R, Thakur AK, Koharudin LMI, Gronenborn AM, et al. Kinetically Competing Huntingtin Aggregation Pathways Control Amyloid Polymorphism and Properties. Biochemistry. 51:2706–16. doi: 10.1021/bi3000929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Colby DW, Chu Y, Cassady JP, Duennwald M, Zazulak H, Webster JM, Messer A, Lindquist S, Ingram VM, Wittrup KD. Potent inhibition of huntingtin aggregation and cytotoxicity by a disulfide bond-free single-domain intracellular antibody. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17616–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408134101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Colby DW, Garg P, Holden T, Chao G, Webster JM, Messer A, Ingram VM, Wittrup KD. Development of a Human Light Chain Variable Domain (VL) Intracellular Antibody Specific for the Amino Terminus of Huntingtin via Yeast Surface Display. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:901–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tam S, Geller R, Spiess C, Frydman J. The chaperonin TRiC controls polyglutamine aggregation and toxicity through subunit-specific interactions. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1155–62. doi: 10.1038/ncb1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tam S, Spiess C, Auyeung W, Joachimiak L, Chen B, Poirier MA, Frydman J. The chaperonin TRiC blocks a huntingtin sequence element that promotes the conformational switch to aggregation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1279–U98. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McLear JA, Lebrecht D, Messer A, Wolfgang WJ. Combinational approach of intrabody with enhanced Hsp70 expression addresses multiple pathologies in a fly model of Huntington’s disease. FASEB J. 2008;22:2003–11. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-099689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wolfgang WJ, Miller TW, Webster JM, Huston JS, Thompson LM, Marsh JL, Messer A. Suppression of Huntington’s disease pathology in Drosophila by human single-chain Fv antibodies. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11563–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505321102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wacker JL, Huang S-Y, Steele AD, Aron R, Lotz GP, Nguyen Q, Giorgini F, Roberson ED, Lindquist S, Masliah E, Muchowski PJ. Loss of Hsp70 Exacerbates Pathogenesis But Not Levels of Fibrillar Aggregates in a Mouse Model of Huntington’s Disease. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9104–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2250-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lotz GP, Legleiter J, Aron R, Mitchell EJ, Huang S-Y, Ng C, Glabe C, Thompson LM, Muchowski PJ. Hsp70 and Hsp40 Functionally Interact with Soluble Mutant Huntingtin Oligomers in a Classic ATP-dependent Reaction Cycle. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38183–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Monsellier E, Redeker V, Ruiz-Arlandis G, Bousset L, Melki R. Molecular Interaction between the Chaperone Hsc70 and the N-terminal Flank of Huntingtin Exon 1 Modulates Aggregation. J Biol Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.603332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li P, Huey-Tubman KE, Gao T, Li X, West AP, Jr, Bennett MJ, Bjorkman PJ. The structure of a polyQ-anti-polyQ complex reveals binding according to a linear lattice model. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:381–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ko J, Ou S, Patterson PH. New anti-huntingtin monoclonal antibodies: Implications for huntingtin conformation and its binding proteins. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56:319–29. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Trottier Y, Lutz Y, Stevanin G, Imbert G, Devys D, Cancel G, Saudou F, Weber C, David G, Tora L, Agid Y, Brice A, Mandel JL. Polyglutamine Expansion as a Pathological Epitope in Huntingtons Disease and 4 Dominant Cerebellar Ataxias. Nature. 1995;378:403–6. doi: 10.1038/378403a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bennett MJ, Huey-Tubman KE, Herr AB, West AP, Ross SA, Bjorkman PJ. A linear lattice model for polyglutamine in CAG-expansion diseases. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11634–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182393899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lecerf JM, Shirley TL, Zhu Q, Kazantsev A, Amersdorfer P, Housman DE, Messer A, Huston JS. Human single-chain Fv intrabodies counteract in situ huntingtin aggregation in cellular models of Huntington’s disease. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4764–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071058398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Steffan JS, Agrawal N, Pallos J, Rockabrand E, Trotman LC, Slepko N, Illes K, Lukacsovich T, Zhu YZ, Cattaneo E, Pandolfi PP, Thompson LM, Marsh JL. SUMO modification of Huntingtin and Huntington’s disease pathology. Science. 2004;304:100–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1092194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pennuto M, Palazzolo I, Poletti A. Post-translational modifications of expanded polyglutamine proteins: impact on neurotoxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R40–R7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ehrnhoefer DE, Sutton L, Hayden MR. Small Changes, Big Impact: Posttranslational Modifications and Function of Huntingtin in Huntington Disease. Neuroscientist. 2011;17:475–92. doi: 10.1177/1073858410390378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dorval V, Fraser PE. SUMO on the road to neurodegeneration. BBA-Mol Cell Res. 2007;1773:694–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Díaz-Hernández M, Valera AG, Morán MA, Gómez-Ramos P, Alvarez-Castelao B, Castaño JG, Hernández F, Lucas JJ. Inhibition of 26S proteasome activity by huntingtin filaments but not inclusion bodies isolated from mouse and human brain. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1585–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Borrell-Pages M, Zala D, Humbert S, Saudou F. Huntington’s disease: from huntingtin function and dysfunction to therapeutic strategies. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2642–60. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.O’Rourke JG, Gareau JR, Ochaba J, Song W, Rasko T, Reverter D, Lee J, Monteys AM, Pallos J, Mee L, Vashishtha M, Apostol BL, Nicholson TP, Illes K, Zhu YZ, Dasso M, Bates GP, Difiglia M, Davidson B, Wanker EE, Marsh JL, Lima CD, Steffan JS, Thompson LM. SUMO-2 and PIAS1 Modulate Insoluble Mutant Huntingtin Protein Accumulation. Cell Reports. 2013;4:362–75. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hannoun Z, Greenhough S, Jaffray E, Hay RT, Hay DC. Post-translational modification by SUMO. Toxicology. 2010;278:288–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Aiken CT, Steffan JS, Guerrero CM, Khashwji H, Lukacsovich T, Simmons D, Purcell JM, Menhaji K, Zhu YZ, Green K, LaFerla F, Huang L, Thompson LM, Marsh JL. Phosphorylation of Threonine 3 Implications for Huntingtin Aggregation and Neurotoxicty. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29427–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Di Pardo A, Maglione V, Alpaugh M, Horkey M, Atwal RS, Sassone J, Ciammola A, Steffan JS, Fouad K, Truant R, Sipione S. Ganglioside GM1 induces phosphorylation of mutant huntingtin and restores normal motor behavior in Huntington disease mice. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3528–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114502109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Thompson LM, Aiken CT, Kaltenbach LS, Agrawal N, Illes K, Khoshnan A, Martinez-Vincente M, Arrasate M, O’Rourke JG, Khashwji H, Lukacsovich T, Zhu YZ, Lau AL, Massey A, Hayden MR, Zeitlin SO, Finkbeiner S, Green KN, LaFerla FM, Bates G, Huang L, Patterson PH, Lo DC, Cuervo AM, Marsh JL, Steffan JS. IKK phosphorylates Huntingtin and targets it for degradation by the proteasome and lysosome. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1083–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Gu XF, Greiner ER, Mishra R, Kodali R, Osmand A, Finkbeiner S, Steffan JS, Thompson LM, Wetzel R, Yang XW. Serines 13 and 16 Are Critical Determinants of Full-Length Human Mutant Huntingtin Induced Disease Pathogenesis in HD Mice. Neuron. 2009;64:828–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Jeong H, Then F, Melia TJ, Mazzulli JR, Cui L, Savas JN, Voisine C, Paganetti P, Tanese N, Hart AC, Yamamoto A, Krainc D. Acetylation Targets Mutant Huntingtin to Autophagosomes for Degradation. Cell. 2009;137:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kalchman MA, Graham RK, Xia G, Koide HB, Hodgson JG, Graham KC, Goldberg YP, Gietz RD, Pickart CM, Hayden MR. Huntingtin is ubiquitinated and interacts with a specific ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19385–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yanai A, Huang K, Kang R, Singaraja RR, Arstikaitis P, Gan L, Orban PC, Mullard A, Cowan CM, Raymond LA, Drisdel RC, Green WN, Ravikumar B, Rubinsztein DC, El-Husseini A, Hayden MR. Palmitoylation of huntingtin by HIP14is essential for its trafficking and function. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:824–31. doi: 10.1038/nn1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kahlem P, Green H, Djian P. Transglutaminase action imitates Huntington’s disease: Selective polymerization of huntingtin containing expanded polyglutamine. Mol Cell. 1998;1:595–601. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Warby SC, Chan EYW, Metzler M, Gan L, Singaraja RR, Crocker SF, Robertson HA, Hayden MR. Huntingtin phosphorylation on serine 421 is significantly reduced in the striatum and by polyglutamine expansion in vivo. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1569–1577. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Humbert S, Saudou F. Huntingtin phosphorylation and signaling pathways that regulate toxicity in Huntington’s disease. Clin Neurosci Res. 2003;3:149–55. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Watkin EE, Arbez N, Waldron-Roby E, O’Meally R, Ratovitski T, Cole RN, Ross CA. Phosphorylation of Mutant Huntingtin at Serine 116 Modulates Neuronal Toxicity. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Atwal RS, Desmond CR, Caron N, Maiuri T, Xia J, Sipione S, Truant R. Kinase inhibitors modulate huntingtin cell localization and toxicity. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:453–60. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Subramaniam S, Sixt KM, Barrow R, Snyder SH. Rhes, a Striatal Specific Protein, Mediates Mutant-Huntingtin Cytotoxicity. Science. 2009;324:1327–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1172871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Jana NR, Dikshit P, Goswami A, Kotliarova S, Murata S, Tanaka K, Nukina N. Co-chaperone CHIP associates with expanded polyglutamine protein and promotes their degradation by proteasomes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11635–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cong X, Held JM, DeGiacomo F, Bonner A, Chen JM, Schilling B, Czerwieniec GA, Gibson BW, Ellerby LM. Mass spectrometric identification of novel lysine acetylation sites in huntingtin. Mol Cell Proteiomics. 2011;10:M111.009829. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.009829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gunawardena S, Her L-S, Brusch RG, Laymon RA, Niesman IR, Gordesky-Gold B, Sintasath L, Bonini NM, Goldstein LSB. Disruption of Axonal Transport by Loss of Huntingtin or Expression of Pathogenic PolyQ Proteins in Drosophila. Neuron. 2003;40:25–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00594-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gauthier LR, Charrin BC, Borrell-Pages M, Dompierre JP, Rangone H, Cordelieres FP, De Mey J, MacDonald ME, Lessmann V, Humbert S, Saudou F. Huntingtin controls neurotrophic support and survival of neurons by enhancing BDNF vesicular transport along microtubules. Cell. 2004;118:127–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lee W-CM, Yoshihara M, Littleton JT. Cytoplasmic aggregates trap polyglutamine-containing proteins and block axonal transport in a Drosophila model of Huntington’s disease. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3224–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400243101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Pal A, Severin F, Lommer B, Shevchenko A, Zerial M. Huntingtin–HAP40 complex is a novel Rab5 effector that regulates early endosome motility and is up-regulated in Huntington’s disease. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:605–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Persichetti F, Trettel F, Huang CC, Fraefel C, Timmers HTM, Gusella JF, MacDonald ME. Mutant Huntingtin Forms in Vivo Complexes with Distinct Context-Dependent Conformations of the Polyglutamine Segment. Neurobiol Dis. 1999;6:364–75. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zheng Z, Li A, Holmes BB, Marasa JC, Diamond MI. An N-terminal Nuclear Export Signal Regulates Trafficking and Aggregation of Huntingtin (Htt) Protein Exon 1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6063–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.413575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kegel KB, Sapp E, Yoder J, Cuiffo B, Sobin L, Kim YJ, Qin ZH, Hayden MR, Aronin N, Scott DL, Isenberg F, Goldmann WH, DiFiglia M. Huntingtin associates with acidic phospholipids at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36464–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503672200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Suopanki J, Gotz C, Lutsch G, Schiller J, Harjes P, Herrmann A, Wanker EE. Interaction of huntingtin fragments with brain membranes - clues to early dysfunction in Huntington’s disease. J Neurochem. 2006;96:870–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Strehlow ANT, Li JZ, Myers RM. Wild-type huntingtin participates in protein trafficking between the Golgi and the extracellular space. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:391–409. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Myre MA, Lumsden AL, Thompson MN, Wasco W, MacDonald ME, Gusella JF. Deficiency of Huntingtin Has Pleiotropic Effects in the Social Amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ritch JJ, Valencia A, Alexander J, Sapp E, Gatune L, Sangrey GR, Sinha S, Scherber CM, Zeitlin S, Sadri-Vakili G, Irimia D, DiFiglia M, Kegel KB. Multiple phenotypes in Huntington disease mouse neural stem cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;50:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jacobsen JC, Gregory GC, Woda JM, Thompson MN, Coser KR, Murthy V, Kohane IS, Gusella JF, Seong IS, MacDonald ME, Shioda T, Lee J-M. HD CAG-correlated gene expression changes support a simple dominant gain of function. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2846–60. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Caviston JP, Holzbaur ELF. Huntingtin as an essential integrator of intracellular vesicular trafficking. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Rockabrand E, Slepko N, Pantalone A, Nukala VN, Kazantsev A, Marsh JL, Sullivan PG, Steffan JS, Sensi SL, Thompson LM. The first 17 amino acids of Huntingtin modulate its sub-cellular localization, aggregation and effects on calcium homeostasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:61–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Michalek M, Salnikov ES, Bechinger B. Structure and Topology of the Huntingtin 1–17 Membrane Anchor by a Combined Solution and Solid-State NMR Approach. Biophys J. 2013;105:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]