Abstract

Giardia lamblia arginine deiminase (GlAD), the topic of this paper, belongs to the hydrolase branch of the guanidine-modifying enzyme superfamily, whose members employ Cys-mediated nucleophilic catalysis to promote deimination of L-arginine and its naturally occurring derivatives. G. lamblia is the causative agent in the human disease giardiasis. The results of RNAi/antisense RNA gene-silencing studies reported herein indicate that GlAD is essential for G. lamblia trophozoite survival and thus, a potential target for the development of therapeutic agents for the treatment of giardiasis. The homodimeric recombinant protein was prepared in E. coli for in-depth biochemical characterization. The 2-domain GlAD monomer consists of a N-terminal domain that shares an active site structure (depicted by an in-silico model) and kinetic properties (determined by steady-state and transient state kinetic analysis) with its bacterial AD counterparts, and a C-terminal domain of unknown fold and function. GlAD was found to be active over a wide pH range and to accept L-arginine, L-arginine ethyl ester, Nα-benzoyl-L-arginine, and Nω-amino-L-arginine as substrates but not agmatine, L-homoarginine, Nα-benzoyl-L-arginine ethyl ester or a variety of arginine-containing peptides. The intermediacy of a Cys424-alkylthiouronium ion covalent enzyme adduct was demonstrated and the rate constants for formation (k1= 80 s−1) and hydrolysis (k2 = 35 s−1) of the intermediate were determined. The comparatively lower value of the steady state rate constant (kcat = 2.6 s−1), suggests that a step following citrulline formation is rate-limiting. Inhibition of GlAD using Cys directed agents was briefly explored. S-nitroso-L-homocysteine was shown to be an active site directed, irreversible inhibitor whereas Nω-cyano-L-arginine did not inhibit GlAD but instead proved to be an active site directed, irreversible inhibitor of the Bacillus cereus AD.

Keywords: L-arginine deiminase, nucleophilic catalysis, L-arginine dehydrolase pathway, mechanism-based inhibition, Giardia lamblia

1. Introduction

L-Arginine is degraded by specialized Archaea (e.g., Korarchaeum cryptofilum, Thermoplasma acidophilum, and Sulolobus tokodaii), Bacteria (e.g., Alistipes putredinis, Rhizobium etli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacillus cereus) and amitochondriate parasitic protists (e.g., Trichomonas vaginalis, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Hexamita inflate and Giardia lamblia) via the arginine dihydrolase (ADH) pathway to generate ATP under anaerobic conditions [1,2]. The ADH pathway consists of three steps, involving (a) hydrolysis of L-arginine (L-Arg) to L-citrulline and ammonia catalyzed by arginine deiminase (AD, EC 3. 5. 3. 6), (b) carbamoyl group transfer from L-citrulline to orthophosphate catalyzed by ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OTC, EC 2.1.3.3) and (c) phosphoryl transfer from carbamoyl phosphate to ADP catalyzed by carbamate kinase (CK, EC 2.7.2.2).

Arginine deiminase (AD) belongs to the guanidine-modifying enzyme superfamily. Members of this family catalyze nucleophilic substitution reactions at the guanidinium carbon atom of L-Arg and its derivatives [3]. The family is divided into the hydrolase branch and the transferase branch. Members of the hydrolase branch include AD, peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD), agmatine deiminase (AgD) and Nω, Nω-dimethylarginine dimethylamidohydrolase (DDAH). The reactions catalyzed by these enzymes (see Fig. 1A) follow a common chemical pathway that involves the intermediacy of a Cys alkyl-thiouronium ion (see Fig. 1B). The catalytic site common to the hydrolases consists of a conserved Cys, which functions in nucleophilic catalysis, a conserved His that participates in acid/base catalysis, and two carboxylate residues that bind the substrate guanidinium group (Fig. 1B). The hydrolases are distinguished on the basis of stringent substrate specificity, which derives from the special tailoring of the binding site for recognition of the appropriate physiological substrate.

Fig. 1.

A. Reactions catalyzed by AD, AgD, DDAH and PAD. B. Common reaction mechanism observed for AD (R= H, R’ = L-CH2CH2CH2CH(COO−)(NH3+)), AgD (R= H, R’ = CH2CH2CH2CH2(NH3+)), DDAH (R= CH3, R’ = L-CH2CH2CH2CH(COO−)(NH3+)) and PAD (R= H, R’ = L-CH2CH2CH2CH(COOEt)(NHBz)).

The folds and active sites of four representative hydrolases are presented in Fig. 2. The segments of the respective catalytic scaffolds and the substrate binding and catalytic residues positioned on these segments are identified in Fig. 2 by using coloring scheme. Comparison of the hydrolases represented in the figure reveals the divergence in structure that has occurred to achieve substrate specificity in each functional family while conserving the catalytic mechanism of the superfamily. For example, the active site of AgDI cannot accommodate the C(α)COO- of L-Arg owing to an unfavorable steric and electrostatic interaction that would occur with the side chain of Glu214 (Fig. 2B) [4,5]. Conversely, agmatine does not substitute for L-Arg as an AD substrate as a result of the missing C(α)COO- group that is required to balance the positively charged side chains of the AD active site residues Arg243 and Arg185 (Fig. 2A) [6–8]. Likewise, the active sites of AD and DDAH have diverged to complement the +H2N=C-NH2 unit of L-Arg and the +H2N=C-N(CH3)2 unit of Nω, Nω-dimethyl-L-arginine, respectively (compare Fig. 2A and 2B) [9,10]. The loops that restrict the entrance of the bacterial AD active site (Fig. 2A) preclude the binding of the Arg side chain of the PAD protein substrate. In Fig. 3A is shown the P. aeruginosa AD modeled with the PAD active site Arg-containing peptide ligand to illustrate the steric clash anticipated to occur with the backbone of an Arg-peptidyl substrate. The absence of the active site gating loops in the PAD structure [11] (Fig. 2D) is consistent with PAD’s preference for a protein substrate.

Fig. 2.

Backbone fold with catalytic scaffold colored (left) and stereodiagram of substrate-binding and catalytic residues, each color coded to coordinate with the color of its locus on the catalytic scaffold (right) for (A) C406A PaAD complexed with L-Arg (PDB ID 2A9G) with a Cys side chain modeled in place of the Ala406 side chain, (B) C249S PaDDAH bound with L- Nω, Nω-dimethylarginine (PDB ID 1H70), (C) AgDI with the carbon atom of the guanindium group of agmatine bonded to the carbon atom of Cys357 (PDB ID 2JER) and (D) PAD H4 bound with Histone 3 N-terminal tail including Arg (PDB ID 2DEW). Ligands are shown in stick representation with carbon atoms colored black, oxygen atoms red and nitrogen atoms blue.

Fig. 3.

A PaAD (PDB ID 2A9G) backbone modeled with the Histone 3 N-terminal tail ligand (shown in stick representation with carbon atoms colored green, nitrogen blue and oxygen red) from the PAD H4 structure (PDB ID 2DEW). The PaAD loop (residue 27–41) that clashes with the ligand is colored red. B. The C406A PaAD tetramer (PDB ID 2A9G) in which the magenta and blue colored subunits represent one dimer unit and the green and yellow colored subunits represent the other dimer unit. The Arg ligand is shown in stick representation with carbon atoms colored black, nitrogen atoms blue and oxygen atoms red.

The work reported in this paper focuses on the AD from Giardia lamblia (GlAD) (ExPasy accession A8BPH7) [12]. G. lamblia is a flagellated protozoan that, when ingested by the consumption of contaminated water or food, infects the human gut and causes the disease giardiasis [13]. The gut provides G. lamblia with an ample supply of L-Arg for energy production via the ADH pathway. In addition to its role as the first catalyst in this pathway, GlAD appears to facilitate G. lamblia colonization through neutralization of the host immune system. Specifically, GlAD was found to catalyze the deimination of the Arg side chain in the conserved CRGKA cytoplasmic tails of G. lamblia variant-specific surface proteins (VSPs) [14]. It was proposed that VSP citrullination influences antigenic switching and antibody-mediated cell death. Earlier, it was reported that AD is among 16 immunodominant proteins in G. lamblia [15] and in a recent study it was shown that upon contact with human epithelial cells G. lamblia releases AD, which in turn serves to diminish NO production and hence, the host immune response [16].

As part of an ongoing program to identify G. lamblia enzymes for the development of therapeutic agents, we selected GlAD for target validation, structure determination, kinetic characterization and inhibitor testing. Firstly, RNAi/antisense RNA silencing experiments were carried out to show that GlAD is essential for trophozoite survival. Secondly, a comprehensive biochemical study was carried out to define AD quaternary structure, catalysis, substrate specificity and inhibition by Cys-modifying substrate analogs. The results of this study are presented and discussed below.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

L-Arginine, L-citrulline, L-homoarginine, agmatine, Nα-benzoyl-L-arginine ethyl ester (BAEE) and SFLLRN-amide oligopeptide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Nω-benzoyl-L-arginine, and L-arginine ethyl ester were obtained from Acros (Hampton, NH). Oligopeptides RAD, RASD and CRGKA were purchased from EZBiolab, Inc‥ Nω-amino-L-arginine was from Alexis Biochemicals (ALX-106-014). Molecular biological materials were purchased from Invitrogen. Nω-Amino-L-citrulline was a gift from Dr. S. Bruce King of the Department of Chemistry at Wake Forest University. Recombinant P. aeruginosa AD (PaAD) was prepared as described in reference [6]. Recombinant Escherichia coli AD (EcAD), Bacillus cereus AD (BcAD), Burkholderia mallei (BmAD) were prepared as described in reference [17]. S-nitroso-L-homocysteine was prepared as described in reference [18]. (S)-2-amino-4-(Z)-2-cyanoguanidino-butanoic acid was prepared by using a modification of the procedure reported by Wagenaar and Kerwin [19].

2.2. DNA preparation

The trophozoites of the G. lamblia isolate WB, clone 1267, were grown axenically at 37 °C in TYI-S-33 medium contained in glass tubes [20]. When monolayers were formed, trophozoites were detached from the surface by chilling on ice for 30 min, harvested by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 10 min, and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline. The pellet was then used for genomic DNA preparation with the DNA Stat kit (Stratagene).

2.3. Arginine Deiminase Gene Cloning, Expression and Protein Preparation

The AD gene from G. lamblia isolate WB clone 1267 was amplified using PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene), genomic DNA, and 5’- and 3’-end primers as follows: forward: 5’-gagaacctgtacttccagggtatgactgacttctccaaggataaagagaag-3’ and reverse: 5’-ggggacaagtttgtacaaaaaagcaggctcggagaacctgtacttccag-3’. The pMBP_AD vector expressing the MBP fusion was constructed using the technique reported by Nallamsetty et al. [21]. The resulting PCR fragment was used as the template for PCR amplification with primers 5’-gagaacctgtacttccagggtatgactgacttctccaaggataaagagaag-3’ (AD_FOR2) and AD_REV. The AD_FOR2 primer is designed to anneal to the sequence encoding TEV protease cleavage site and add an attB1 recognition site to the end of the amplicon. The resulting PCR fragment was inserted into pDNOR221 (Invitrogen) by recombinational cloning with BP clonase mix using the standard Gateway protocol (Invitrogen). The nucleotide sequence of the entry clone pAD221 was verified by DNA sequencing. The His6MBP_AD (pMBP_AD) fusion protein expression vector was constructed using the LR clonase enzyme mix (Invitrogen) to recombine the AD ORF from the pAD221 entry vector with the destination vector pDEST-His MBP. Site-directed mutants were prepared from the pMBP_AD using commercial primers and the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). E. coli BL21 Star(DE3) cells transformed with the AD expression vector were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria broth (LB) in the presence of 50 µg/mL carbenicillin with shaking at 180 rpm. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (6500 rpm, 15 min, 4°C) yielding ca. 3 g cells/L of culture media. The cell pellets were suspended in ice cold buffer A (50 mM K+HEPES containing 1 mM DTT, pH 7.5; 1 gm/10 mL) and then passed through a French Press at 1200 PSIG and centrifuged (20,000 rpm, 30 min, 4°C). The supernatant was loaded onto a 40 cm × 5 cm DEAE-cellulose (Sigma) column at 4°C, and the column was eluted with 1 L buffer A followed by a 2 L linear gradient of 0 to 0.5 M KCl in buffer A. AD-containing fractions were identified by measuring absorbance at 280 nm and by SDS-PAGE analysis. Selected fractions were combined, adjusted to 10 % (g/mL) in ammonium sulfate and loaded onto an 18 cm × 3 cm Butyl-Sepharose column (Sigma) pre-equilibrated with purification buffer containing 10% (g/mL) ammonium sulfate. The column was eluted at 4 °C with 300 mL of buffer A containing 10 % (g/mL) ammonium sulfate followed by a 800 mL linear gradient of 10% (g/mL) to 0% ammonium sulfate in buffer A. The combined AD-containing fractions were reduced in volume to 10 mL using an Amicon device (10 kDa Disc membrane) and then TEV protease was added in a 1:10 molar ratio to cleave the His6-tag. Following a 15 h incubation period at 4°C, the mixture was loaded onto a 15 cm × 2 cm Ni-NTA column (Sigma) pre-equilibrated with buffer B (5 mM imidazole, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.5) and eluted with the same buffer. The AD-containing fractions were chromatographed on a Butyl-Sepharose column as described above. The AD-containing fractions were concentrated using an Amicon device (10 kDa Disc membrane) followed by a 10 kDa Macrosep centricon (Pall Filtron) device, and then dialyzed against buffer A. The protein purity was verified by SDS-PAGE analysis. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method and by measuring the protein absorbance at 280 nm (extinction coefficient = 55, 405 M−1 cm−1). The C424A GlAD mutant was purified as described above for the wild-type enzyme and its purity was verified by SDS-PAGE analysis. The yields of homogeneous GlAD in units of milligrams of protein per gram of wet cells are as follows: wild-type (0.3) and C424A (0.4).

2.4. Functional knockout of the GlAD gene in G. lamblia

The GlAD gene was inserted into the plasmid pdsRNA between two opposite tetracycline-inducible Ras-related nuclear GTP-binding protein (ran) promoters, and knockout experiments were carried out as described previously [22].

2.5. Determination of AD molecular mass

The AD subunit molecular mass was determined by ESI-MS analysis (University of New Mexico Mass Spectrometry Facility). The mass of the native complex was determined by HPLC size exclusion chromatography/laser light scattering (Yale University) or by FPLC size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 Hi-Load 16/60 column) using commercial protein molecular standards.

2.6. GlAD activity assays and steady-state kinetic constant determination

The fixed-time colorimetric assay used for determination of citrulline was adapted from published procedures [23]. Briefly, at a specific time point, an aliquot (250 μL) of the reaction solution was withdrawn and mixed with 1 mL of a mixture of one part oxime reagent (0.8 gm of 2, 3-butanedione 2-oxime in 100 mL of 5 % acetic acid) and two parts of antipyrine/sulfuric acid reagent (5 gm of antipyrine in 1 L of 50 % sulfuric acid). The mixture was placed in a 60 °C water bath for 80 min, after which its absorbance at 466 nm was promptly measured. The continuous spectrophotometric assay used for determination of ammonium ion generated by GlAD-catalyzed L-Arg deimination is based on a reported procedure [24]. Reaction solutions initially contained L-Arg, GlAD, and the coupling system that consists of 1.8 mg/mL glutamate dehydrogenase (bovine liver, type II), 10 mM α-ketoglutarate, and 0.2 mM NADH in 50 mM K+HEPES (pH 7.5). The progress of the reaction was monitored at 25 °C by measuring the decrease in the absorbance at 340 nm (Δε = 6.22 mM−1 cm−1).

The kcat and Km values were determined by measuring the initial velocity of the AD catalyzed reaction as a function of substrate concentration. The initial velocity data were fitted to Eq. (1) using KinetAsystI.

| (1) |

where V is the initial velocity, Vmax is the maximum velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration and Km is the Michaelis constant. The kcat value was calculated from the Vmax and enzyme concentration ([E]) according to the equation kcat = Vmax/[E].

2.7. GlAD pH rate profile determination

The buffers used for pH rate profile determinations are as follows: 25 mM MES and 25 mM acetate (pH 5.0); 50 mM MES (pH 5.6); 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 6.0 and 6.5); 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.0 and 7.5); 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0); 50 mM TAPS (pH 8.5); CHES (pH 9–9.5); CAPS (pH 10–10.5). Initial velocities of GlAD catalyzed L-Arg deimination were measured at different solution pH values, as a function of L-Arg concentration (0.5–10 Km), by using the fixed-time colorimetric assay described above. The kcat/Km values calculated from the initial velocity data were fitted to Eq. (2) for the ionization of an essential acid and the ionization of the protonated form of an essential base.

| (2) |

where Y is the kcat or the kcat/Km, H is the proton concentration of the reaction buffer, Ka and Kb are the apparent ionization constants of the acidic and basic groups, and C is the constant.

2.8. Single-turnover time course determination by rapid quench

The single turnover reactions (27 µL) of 150 µM GlAD (wild-type or C424A mutant) or 150 µM EcAD (wild-type or C397S mutant) with 10 µM [14C-1]-L-Arg in 50 mM K+HEPES (pH 7.5, 25 °C) (for GlAD) or 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 6.0, 25 °C)/20 MgCl2 (for EcAD) were carried out in a KinTek rapid quench instrument. Reaction solutions were quenched with 193 µL of 0.6 M HCl and then vigorously mixed with 60 µL of CCl4 using a vortex mixer. The mixture was centrifuged at 14, 000 rpm for 2 min, the supernatant was removed, and the protein pellet was carefully blotted with a piece of Kimwipe© paper. The dried pellet was mixed with 4 mL of scintillation fluid for scintillation counting. The supernatant was transferred to a 5 KD centrifugal filter device (Ultrafree-MC) and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min. [14C-1]-L-Citrulline and [14C-1]-L-Arg were separated from the filtrate by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The Beckman ultrasphere ODS reverse column (4.6 mm × 25 cm, 5 μ) was eluted with a linear gradient of buffer C (25 mM phosphoric acid, 10 mM hexanesulphoric acid, 0.5% (V/V) acetonitrile, pH = 2.5) and buffer D (25 mM phosphoric acid, 10 mM hexanesulphoric acid, 20% (V/V) acetonitrile, pH = 2.5). The gradient program was 100% buffer C for 8 min, 0–100% buffer D for 2 min, hold at 100% buffer D for 10 min, 0–100% buffer C for 1 min, finally hold at 100% buffer D for 9 min. The absorbance of the eluant was monitored at 200 nm. The retention times of L-Arg and L-citrulline standards were 15 min and 9 min, respectively. The [14C-1]-L-arginine and [14C-1]-L-citrulline fractions were analyzed by liquid scintillation counting. Control reactions, for which the acid quench was added to the enzyme before the addition of [14C-1]-L-Arg, were carried out to establish the “background” for radiolabeled enzyme which was typically < 0.4 %. The L-Arg, and L-citrulline time course data were fitted to the first-order rate Eq. (3) and (4), respectively,

| (3) |

| (4) |

where “k” is the first-order rate constant; [S]t and [P]t are the substrate and product concentrations at time “t”. The time course measured for the radiolabeled enzyme was fitted using the simulation program KINSIM [25] and the kinetic model shown in Eq. (5),

| (5) |

where ES is the GlAD complex of [14C-1]-L-Arg, EI is the radiolabeled GlAD and EP is the GlAD complex of [14C-1]-L-citrulline.

2.9. Determination of kinetic constants for AD alternate substrates

The steady-state kinetic constants for AD alternate substrates were measured using the fixed-time colorimetric assay to monitor citrulline formation or the continuous spectrophotometric assay to monitor ammonium ion formation. The kcat and Km values were determined from initial velocity data as described above.

2.10. Determination of inhibition constants for reversible inhibitors

The reversible inhibition constants Kii and/or Kis were determined using the continuous spectrophotometric assay. The 0.5 mL reaction solutions initially contained 50 mM K+HEPES (pH 7.5), varying concentrations of L-Arg and several fixed concentrations of inhibitor. The competitive inhibition constant Kis was determined by fitting the initial velocity data to Eq. (6) with KinetAsystI, and the Kii and Kis for mixedtype inhibition were determined by fitting the initial velocity data to Eq. (7) with KinetAsystI.

| (6) |

| (7) |

where V is the initial velocity, Vmax is the maximum velocity, [S] is the substrate concentration, Km is the Michaelis constant, [I] is the inhibitor concentration, is Kis the slope inhibition constant, and Kii is the intercept inhibition constant.

2.11. Time and concentration dependent inactivation of GlAD and BcAD

BcAD or GlAD and the inhibitor (S-nitroso-L-homocysteine or (S)-2-amino-4-(Z)-2-cyanoguanidino-butanoic acid) were incubated in 50 mM K+HEPES (pH 7.0) at 25 °C. At various time points, aliquots (5 μL) were removed and diluted 100-fold into the assay solution (5 mM L-Arg, 1.8 mg/mL glutamate dehydrogenase, 10 mM α-ketoglutarate, and 0.2 mM NADH in 50 mM K+HEPES at pH 7.0 and 25 °C) to measure remaining AD activity. The pseudo-first-order rate constants for the inactivation reactions (kobs) were calculated using Eq. (8),

| (8) |

where at is the activity of AD incubated with inhibitor for a specified time (t) and a0 is the activity of AD incubated in buffer for the same time period.

The binding constant (KI) and rate constant (kinact) for inactivation were calculated by the kobs values measured as a function of inhibitor concentrations “[I]” to Eq. (9) using Kaleidagraph.

| (9) |

2.12. Reaction of Nω-amino-L-arginine with AD

Inactivation tests with the respective ADs were carried out at 25 °C by incubating Nω-amino-L-arginine (5 mM) and AD (3 μM) in buffer at the optimal pH. At various time points, aliquots were removed and diluted 100-fold into an activity assay solution (see above) to measure the AD activity. The products formed in the reaction of the AD with the Nω-amino-L-arginine were confirmed by ESI-MS analysis (L-citrulline 176 Da and N-amino-L-citrulline 191 Da) and by HPLC analysis (see separation protocol above; retention times are: 2.5–3 min for hydrazine, 8–9 min for L-citrulline and 14–15 min for Nω-amino-L-arginine). The steady-state kinetic constants kcat and Km for AD catalyzed hydrolysis of Nω-amino-L-arginine to hydrazine and citrulline were determined by using the colorimetric assay and the steady-state kinetic methods described above.

2.13. Modeling

Molecular modeling, structural alignment and model visualization were carried out with the QUANTA software package (Molecular Simulations Inc.). The three-dimensional model of GlAD was generated based on homology with the PaAD structure (PDB code 2a9g) using the 3D-JIGSAW protein comparative modeling server (http://bmm.cancerresearchuk.org/~3djigsaw/) [26]. Several side chains around the substrate-binding site were adjusted manually using the QUANTA rotamer library.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. RNAi/antisense RNA gene silencing

G. lamblia derives ATP via the glycolytic and ADH pathways [13]. Previously, RNAi/antisense RNA gene-silencing techniques were used to provide evidence that the G. lamblia fructose-1, 6-bisphosphate aldolase is essential for trophozoite survival in culture [27]. In the present study, this same method was applied to reduce GlAD levels in cultured trophozoites. As was observed in the fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase knockdown experiment, trophozoites transfected with the silencing plasmid yielded no viable organisms. This finding is consistent with the proposal that GlAD plays a crucial role in G. lamblia, and as a result, we conclude that GlAD is a promising candidate for drug targeting.

3.2. Preparation of recombinant GlAD

Key to our planned studies of GlAD catalysis was the preparation of recombinant enzyme. Shortly following the isolation of native GlAD from cultured G. lamblia trophozoites reported by Edwards and coworkers in 1997 [12], the protocol for production of the recombinant enzyme in E. coli was published [28]. For reasons that are currently unknown, our initial attempts to generate a GlAD producing E. coli clone, by using standard expression systems, failed. Ultimately, a maltose binding protein (MBP) fusion construct proved to be effective, and upon removal of the MBP domain soluble, homogenous GlAD was obtained in an adequate yield (0.3 mg/gm wet cells; see SDS-PAGE gel in Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

A. SDS-PAGE gel of purified recombinant GlAD shown in the right lane and protein molecular weight standards shown in the left lane. B. The kcat (○) and kcat/Km (●) pH profiles for GlAD catalyzed L-Arg deimination. The kcat/Km profile data were fitted with Eq. (2). The acid range data defined an apparent pKa = 4.3.

3.3. Quaternary structures of GlAD and representative bacterial ADs

The first step in characterizing the recombinant GlAD was to determine its subunit mass and its native mass (Table 1). GlAD is unique in that it possesses a 140 amino acid long C–terminal domain. The fold and function of this domain are not known and this caused us to query whether the domain impacts GlAD subunit association. The subunit and native masses reported for M. arginini AD (MaAD) [8] and P. aeruginosa AD (PaAD) [29] are listed in Table 1 along with the masses determined in this study for E. coli AD (EcAD), B. cereus AD (BcAD), B. mallei (BmAD) and GlAD. EcAD is a monomer, GlAD and MaAD are homodimers, whereas PaAD and BcAD are homotetramers. Crystallographically, MaAD was observed as a dimer [8] whereas the PaAD (shown in Fig. 3B) [29] and BcAD [30] were characterized as dimers of dimer. The GlAD C-terminal domain does not impede formation of the subunit-subunit interface of the dimer. This indicates that the C-terminal domain does not associate with the region of the monomer responsible for dimer formation. It also should be noted that in each AD structure, the substrate-binding site is removed from the subunit interfaces (see Fig. 3B) and, as a result, it is self-contained. This location might account for the catalytically active monomeric form represented by the AD from E. coli.

Table 1.

AD Subunit Size and Quaternary Structure.

3.4. Construction of a three-dimensional model of the GlAD catalytic domain

So far, attempts to determine the crystal structure of GlAD have not been successful. On the other hand, the reported crystal structures of MaAD, PaAD and BcAD [7,8,30] provided us with structural templates for the construction of a three-dimensional model of the GlAD N-terminal (“catalytic”) domain (residues 1–434). The GlAD model, shown in Fig. 5, was generated using the C406A PaAD monomer bound with L-Arg [7] as the modeling template. The model is biased by the structure of the template but, nevertheless, an effective visual aid in the evaluation of the GlAD catalytic and substrate-binding residues. A comparison of the modeled GlAD active site (Fig. 5B) with the active sites of PaAD [7] (shown in Fig. 2A), BcAD [30] and MaAD [8] indicates that all substrate binding and catalytic residues as well as the catalytic scaffold on which they are positioned, are conserved. There is no indication that the entrance of the GlAD active site is less restricted than those of its bacterial counterparts. We make note of this observation in reference to the reported GlAD peptidyl arginine deiminase activity [14], with the caveat that the model might not accurately depict the conformations of the active site gating loops.

Fig. 5.

A. Superposition of the GlAD model (green) and the structure of the C406A PaAD(L-Arg) complex (PDB ID 2A9G) (red). The L-arginine ligand shown in black stick representation. B. Stereodiagram of the active site residues of the modeled GlAD(L-Arg) with carbon atoms colored grey, oxygen atoms red and nitrogen atoms blue.

3.5. Steady-state kinetic analyses of GlAD catalyzed L-Arg deimination

Given that the GlAD and bacterial ADs catalytic and substrate binding residues are conserved, a common catalytic mechanism is anticipated. However, because these invariant “frontline residues” perform within the context of neighboring residues that are not stringently conserved (identity between some sequence pairs is less than 20%!), the catalytic efficiencies of the ADs will not necessarily be equivalent. Nevertheless, with one exception (MaAD) the steady-steady kinetic constants measured at the pH optimum are very similar (see Table 2). On the other hand, the large deviation in the pH range for maximal catalytic activity observed for the ADs is striking. PaAD, BmAD and EcAD for example, are maximally active at pH 5. In contrast, the BcAD is maximally active at pH 7.0 [17]. The GlAD pH rate profiles, on the other hand (see Fig. 4B), define a broad pH range for catalysis. The kcat value for GlAD is maximal from pH 5.5 to pH 9.0 and the kcat/Km value is maximal between pH 6 and 8. The variation in the AD pH rate profiles might derive from AD specific, pH-sensitive residues that influence the function of the catalytic residues. Also, the different reaction steps catalyzed by AD involve different constellations of pH sensitive ionization states. The extent to which each reaction steps is rate limiting will influence the pH rate profile.

Table 2.

Comparison of the steady-state kinetic constants for AD-catalyzed conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline plus ammonia measured at the pH optimum and 25 °C.

3.6. Rapid quench studies of AD catalyzed single turnover reactions

The rate-limiting step(s) of the GlAD catalysis was investigated by using transient kinetic techniques to measure the apparent rate constant for the formation of the GlAD-Cys424- alkythiouronium ion intermediate and the apparent rate constant for the hydrolysis of the intermediate to L-citrulline (Fig. 1B). Rapid quench techniques were employed to trap the GlAD-Cys424-[14C]alkythiouronium ion intermediate formed during the course of a single turnover reaction of the GlAD([14C]-L-Arg) complex. The concentrations of [14C]-L-Arg, [14C]-L-citrulline and GlAD-Cys424-[14C]alkythiouronium ion were measured as a function of reaction time to generate the time courses shown in Fig. 6A and 6B. Control reactions were carried out in parallel using the catalytically inactive C424A GlAD mutant in place of the wild-type GlAD. The [14C]-L-Arg decay curve and the [14C]-L-citrulline formation curve were fitted to Eq. (3) and (4), respectively, to define the apparent rate constants kArg = 31 ± 2 s−1 and kcitrulline = 27 ± 2 s−1. Next, the complete data set was fitted using the simulation program KINSIM [25] and the kinetic model shown below in order to define the values of the microscopic rate constants that are reported in Table 3.

Fig. 6.

Time courses for the single turnover reaction of 10 µM [14C-1]-L-Arg catalyzed by 150 µM GlAD (wild-type or C397S mutant) in 50 mM K+HEPES (pH 7.5, 25 °C) or 150 µM EcAD (wild-type or C424A) in 50 mM Bis-Tris (pH 6.0)/20 MgCl2. A. GlAD time courses: [14C-1]-L-arginine (●) and [14C-1]-L-citrulline (○). B. GlAD time courses: [14C]-labeled wild-type GlAD (●) and (○)[14C]-labeled C424A AD. C. EcAD time courses: [14C-1]-L-arginine (●) and [14C-1]-L-citrulline (○). D. EcAD time courses: [14C]-wild-type EcAD (●) and (○)[14C]-labeled C397S EcAD.

Table 3.

The rate constant k1 = 80 s−1 actually governs two reaction steps: the first step leads to a tetrahedral intermediate (formed by the addition of the Cys thiolate anion to the L-Arg gaundinium carbon atom) and the second step to the thiouronium ion intermediate (shown in Fig. 1B and represented in the kinetic model). Likewise, the rate constant k2 = 35 s−1 governs the step leading from the Cys424-alkylthiouronium ion intermediate to the corresponding tetrahedral intermediate (formed by addition of the activated water molecule at the thioruonium carbon atom) and hence, to L-citrulline. Both rate constants exceed the steady-state rate constant kcat= 2.6 s−1, which indicates that a step or steps (viz. a conformational change and/or ligand dissociation) following L-citrulline formation might be rate limiting.

The analogous experiment was carried out with EcAD (see time courses in Fig. 6C and 6D) to define k1 = 11.5 s−1 and k2 = 5.5 s−1. These values are significantly smaller than the corresponding values determined for GlAD. The kinetic behavior of PaAD [31] is essentially the same as that of EcAD (Table 3). BcAD on the other hand, is a bit more efficient (k1 = 50 s−1 and k2 = 9 s−1) [30]. For all ADs examined k1 > k2. Only in the case of the GlAD, is the turnover rate limited by a step that follows L-citrulline formation. This may account, at least in part, for GlAD’s uniquely “flat” kcat profile (Fig. 4B).

3.7. In vitro tests of GlAD peptidylarginine deiminase activity

As mentioned above, the model of GlAD suggests that the substrate specificity elements of the bacterial ADs are conserved in the GlAD. Nevertheless, the reported [14] GlAD catalytic activity towards deimination of the side chain of the Arg residue located in the conserved CRGKA cytoplasmic tails of the G. lamblia variant-specific surface proteins (VSPs) suggests that GlAD possesses peptidylarginine deiminase activity in addition to its known AD activity. The in vitro activity assay, used for the detection of the C-terminal His6-tagged GlAD (purified from transgenic G. lamblia trophozoites) catalyzed deimination of 5 mM His6-CRGKA, reportedly employed a high reaction temperature (50 °C) in conjunction with a long incubation period (16 h) and an especially sensitive product assay (viz. Western blot analysis using an anti-citrulline antibody). Based on the nature of the assay, we suspect that the GlAD catalyzed demination occurred very slowly. The activity of the recombinant GlAD (50 µM), prepared in E. coli, towards Arg-containing peptides as well as the Arg peptide model Nα-benzoyl-arginine ethyl ester (“BAEE” which is commonly used to measure PAD activity) was evaluated. Substrate activity was measured by continuously monitoring the formation of ammonia in reaction solutions containing 50 µM GlAD and 10 mM reactant in 50 mM K+HEPES (pH 7.5, 25 °C) for 30 min. A single turnover reaction would result in an absorbance change of 0.31 OD. For the peptides RAD, RASD, SFLLRN-NH2 (C-terminus is O=C-NH2 instead of COO−) and CRGKA no absorbance change was detected and therefore we conclude that the turnover rate must be less than 1 ×10−4 s−1. The same result was obtained for BAEE, even though BAEE was shown by subsequent competitive inhibition studies to bind (albeit weakly) to the GlAD active site (Kis = 7 ± 1 mM). For comparison purposes, the reported kinetic constants for human protein arginine deiminase 4-catalyzed BAEE deimination are kcat = 6 s−1 and Km = 1.4 mM [32]. Because PAD requires Ca2+, GlAD activity towards BAEE was also tested in the presence of 5 mM CaCl2, but still product formation was not detected. Although it is reasonable to infer from the results of these in vitro kinetic determinations that GlAD is not optimized for peptidyl-arginine deiminase activity, the existence of a very slow, yet physiologically relevant deiminase activity directed at the CRGKA cytoplasmic tails of G. lamblia VSPs, cannot be dismissed.

3.8. GlAD substrate specificity

The residues that form the L-Arg CH(COO−)(NH3+) binding pocket in the bacterial ADs are conserved in the GlAD active site (see Fig. 2A and Fig. 5B). In order to characterize GlAD substrate specificity, activity tests were carried out with L-Arg analogs modified at the CH(COO−)(NH3+) moiety. Firstly, agmatine (Arg without the α-COO−), shown in a previous study to have no detectable substrate activity with PaAD [6], was shown in this work to be unreactive with GlAD. Inhibition studies defined agmatine as a very weak, mixed-type inhibitor of GlAD: Kis = 50 ± 10 mM and Kii = 120 ± 20 mM. L-Arginine ethyl ester on the other hand, undergoes GlAD catalyzed deimination (kcat = 2.3 s−1 vs 2.6 s−1for L-Arg) but with a significantly increased Km value (2.1 mM vs 0.16 mM for L-Arg). This analog was also tested as a substrate for EcAD and BcAD and no activity was detected. Nα-Benzoyl-arginine too proved to be an active substrate for GlAD (kcat = 2.5 s−1, Km = 2.3 mM) but not for EcAD or BcAD. These results suggest that GlAD tolerates mono-alkylation (but not di-alkylation as in BAEE) at the CH(COO−)(NH3+) units, whereas its bacterial counterparts do not. Thus, despite the perceived similarity of AD substrate binding sites, something is clearly unique about the GlAD site, too subtle to glean from the model, but nevertheless significant enough to cause a small change in the substrate specificity.

L-Homoarginine (L-Arg with one additional CH2 unit) is not a GlAD substrate (nor a substrate for the bacterial ADs [33,34]) but rather a weak binding competitive inhibitor (Kis = 48 ± 6 mM). Together, these substrate screening results provide a guide to the design of mechanism-based inhibitors (see below), and suggest the requirement that these inhibitors possess a L-CH2CH2CH2CH(COO−)(NH3+) unit to insure effective active site targeting.

3.9. Investigation of AD inhibition by active site directed L-Arg analogs

Two designs of Cys-directed GlAD covalent inhibitors are illustrated in Fig. 7A and 7B. One involves the use of an Arg analog to deliver an electrophilic “warhead” to the active site Cys424 nucleophile (Fig. 7A). The other employs an Arg analog, modified at the guanidinium moiety, that will undergo the first partial reaction but not the second (see Fig. 7B). Both inhibitor designs are based on earlier studies of mechanism-based inhibitors of the Cys protease papain.

Fig. 7.

Schemes depicting the reaction of the GlAD Cys424 with (A) a L-Arg analog carrying an electrophilic “warhead”, (B) a L-Arg analog modified with a group “Y” that blocks the hydrolysis partial reaction, (C) S-nitroso-L-homoseine, (D) Nω-cyano-L-Arg and (E) Nω-amino-L-Arg.

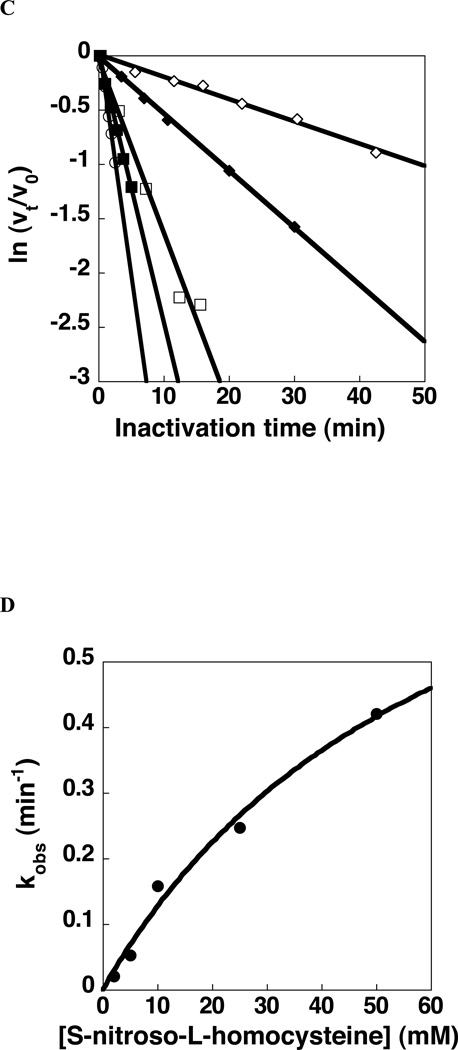

The first inhibitor explored is S-nitroso-L-homocysteine (Fig. 7C). This compound has previously been shown to modify protein Cys residues, most notably those of mammalian DDAHs, by nitrosylation and/or by formation of the corresponding N-thiosulfoximide adduct [35,36]. Accordingly, S-nitroso-L-homocysteine (2–90 mM) and GlAD (10 µM) were incubated in 50 mM K+HEPES (pH 7.5, 25 °C). Aliquots were removed, after various incubation periods, for GlAD activity determination. The value of kobs for inactivation was determined from the slope of the plot of the percent remaining GlAD activity vs. incubation time (Fig. 8A). The curvature observed in the plot of kobs vs. S-nitroso-L-homocysteine concentration (Fig. 8B) indicates a two-step inactivation sequence in which the binding of S-nitroso-L-homocysteine to GlAD is followed by covalent modification. The inactivation constants KI = 40 ± 10 mM and kinact = 0.17 ± 0.02 min−1 were determined by data fitting to Eq. (9). The activity of GlAD was not regained following dialysis for 10 h. This finding indicates that irreversible inhibition has taken place. On the other hand, the covalent adduct formed by incubation of 10 µM GlAD with 10 mM S-nitroso-L-homocysteine in 50 mM K+HEPES (pH 7.0, 25 °C) for 1 h was not detected by ESI-MS analysis. We therefore turned our attention to the bacterial ADs in hope that the S-nitroso-L-homocysteine derived Cys-adduct formed using one of these might survive ionization in the mass spectrometer. The inactivation data observed for BcAD (Fig. 8C and 8D) are similar to those determined for GlAD (Fig. 8A and 8B) and they define the inactivation constants KI = 66 ± 30 mM and kinact = 1.0 ± 0.3 min−1. The ESI-MS spectrum of the inactivated (24 µM enzyme incubated 30 min with 10 mM S-nitroso-L-homocysteine in 50 mM K+HEPES pH 7.0, 25 °C) BcAD (native mass 46638 Da) showed peaks at 46968 Da (+30 Da), 46998 Da (+60 Da), 47027 Da (+88 Da), 47131 Da (+193 Da) and 47162 Da (+224 Da). Apparently, all three BcAD cysteine residues (each solvent accessible) [30] are subject to modification to form the corresponding S-nitroso adduct (+29 Da) or the N-thiosulfoximide adduct (+164 Da) (pictured in Fig. 7C).

Fig. 8.

Time- and concentration-dependent inactivation of S-nitroso-L-homocysteine to GlAD (10 μM) at pH 7.5, 50 mM HEPES and 25°C. (A) Plot of ln(vt/v0) vs. time. 2 mM (◇), 5 mM (◆), 10 mM (□), 30 mM(■), 60 mM (○), and 90 mM (●) of S-nitroso-L-homocysteine. (B) Plot of kobs vs. S-nitroso-L-homocysteine concentration with data fitted to the Eq. (9) to obtain KI and kinact values. Time and concentration dependence of the inactivation of BcAD (12 μM) by S-nitroso-L-homocysteine in 50 mM K+HEPES at pH 7.0 and 25 °C. (C) Plot of ln(vt/vo) vs time. 2 mM (◇), 5 mM (◆), 10 mM (□), 25 mM (■) and 50 mM (○) S-nitroso-L-homocysteine. (D) Plot of kobs vs S-nitroso- L-homocysteine concentration with data fitting to Eq. (9). Time and concentration dependence of the inactivation of BcAD by Nω-cyano-L-Arg in 50 mM K+HEPES at pH 7.0 and 25 °C. (E) Plot of ln(vt/vo) vs time. 0 mM (◇), 5 mM (◆), 10 mM (□), 20 mM (■) and 40 mM (○) Nω-cyano-L-Arg. (F) Plot of kobs vs Nω-cyano-L-Arg concentration with data fitting to Eq. (9).

In contrast to GlAD and BcAD, S-nitroso-L-homocysteine inactivation of DDAH is reported to follow second order kinetics (k = 4 M−1 s−1 [35]; k = 9 M−1 s−1 [37]). X-ray crystallographic analysis of inactivated DDAH showed that the active site Cys undergoes N-thiosulfoximide adduct formation and that the surface Cys residue undergoes S-nitrosylation [38].

Even though GlAD (and BcAD) binds S-nitroso-L-homocysteine at the active site, the binding is weak compared to substrate binding. This is because, without the guandinium group of the L-Arg, the favorable ligand binding energy derived from hydrogen bond interaction with Asp175 and Asp282 and ion pair formation with the Cys424 thiolate anion is lost (see Fig. 4B). In order to saturate the active site a high concentration of S-nitroso-L-homocysteine is required and this, in turn, is expected to enhance the rate of collision-based reactions of surface Cys residues. Furthermore, at pH 7.0, the Cys-thiol is protonated. Bound L-Arg dramatically reduces the pKa of the AD active site Cys-thiol so that it is ionized for nucleophilic addition [17]. Because the S-nitroso group of the S-nitroso-L-homocysteine ligand is not positively charged, we anticipate that its binding will not cause a large reduction in the pKa of the active site Cys-thiol. Consequently, the protonation state of the active site Cys-thiol might not differ dramatically from those of the surface Cys-thiols. Because BcAD possesses two surface Cys residues [30], it is therefore not surprising that all three BcAD Cys residues are were modified by the S-nitroso-L-homocysteine.

Attention was next directed to the L-Arg analog (S)-2-amino-4-(Z)-2-cyanoguanidino-butanoic acid (Nω-cyano-L-Arg; Fig. 7D). The results from previous work had shown that peptide analogs functionalized with a cyano group inhibit papain via formation of the corresponding thioimidate adducts [39–42]. Thus, one possible pathway for Nω-cyano-L-Arg induced GlAD inactivation is nucleophilic attack of the GlAD Cys-residue on the cyano carbon to form the conjugated covalent adduct depicted in Fig. 7D. Alternatively, nucleophilic addition of the GlAD Cys-thiolate anion at the guanidinium carbon, followed by loss of ammonium ion might lead to a dead-end Cys-thioureido adduct (Fig. 7D). When Nω-cyano-L-Arg (40 mM) was tested as a GlAD inhibitor neither reversible nor irreversible inhibition was observed. On the other hand, incubation of BcAD (6 μM) with varying concentrations of Nω-cyano-L-Arg (0–40 mM) resulted in time- and concentration-dependent loss of enzyme activity (Fig. 8E and F). The pseudo-first order rate constants of inactivation (kobs), determined for each inhibitor concentration, are plotted in Fig. 8F to show that the value of kobs increases with increasing inhibitor concentrations until BcAD becomes saturated. The data were fitted to obtain the kinact and KI values of 0.15 ± 0.04 min−1 and 20 ± 10 mM, respectively. The inactivation was found to be irreversible by employing overnight dialysis against 50 mM K+HEPES/1 mM DTT at pH 7.5 and 4 °C. However, analysis of the inactivated enzyme by ESI-MS failed to detect the modified enzyme and therefore, the structural basis for inactivation is not known nor is the reason why Nω-cyano-L-Arg inactivates BcAD but not GlAD.

The reaction between GlAD and Nω-amino-L-arginine (Nω-amino-L-Arg) was examined next. Two possible reaction pathways can be envisioned (Fig. 7E). One of these leads to loss of ammonia with the formation of the corresponding Nω-amino substituted Cys-alkylthiouronium ion adduct and the other to loss of hydrazine and the formation of the authenic Cys-alkylthiouronium ion intermediate. GlAD was preincubated with 10 mM Nω-amino-L-Arg, and then assayed for L-Arg deiminase activity. No activity reduction was observed to occur over a 1 h preincubation period. The same result was obtained for EcAD, BmAD and BcAD. On the other hand, Nω-amino-L-Arg proved to be an active substrate. Product analysis using HPLC and mass spectral techniques, in conjunction with citrulline and Nω-amino-L-citrulline chemical standards (see Materials and Methods for details), showed that the reaction pathway catalyzed by each of the ADs proceeds with the displacement of hydrazine rather than ammonia. Thus, productive binding places the hydrazine substituent in the leaving group binding pocket (see Fig. 2A and 4B). The steady-state kinetic constants measured for AD catalyzed Nω-amino-L-Arg hydrolysis reported in Table 4, indicate that the Nω-amino substituent increases the substrate’s Km value but does not decrease its kcat value. Even though the Nω-amino-L-Arg is a substrate rather than an inhibitor it still might be used against G. lamblia trophozoites because the hydrazine that is produced by the AD in situ is potentially toxic.

Table 4.

The steady-state kinetic constants of AD catalyzed hydrolysis of Nω-amino-L-arginine to hydrazine and L-citrulline.

| AD | pH | kcat (s−1) | Km (µM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EcAD | 6.0 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 10 ± 2 | 1.0 × 102 |

| BmAD | 5.6 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 90 ± 10 | 3.3 × 101 |

| GlAD | 7.5 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.9 × 102 |

| PaADa | 5.6 | 7 ± 2 | 50 ± 20 | 1.4 × 102 |

| BcAD | 7.0 | 0.44 ± 0.02 | 7 ± 1 | 6.3 × 101 |

Reported in reference [6].

4. Conclusion

The studies described above have provided insight into GlAD structure and function. Based on the results of the GlAD gene knockdown experiment, GlAD appears to be a viable candidate for drug development. Moreover, the GlAD catalytic Cys is an obvious target for an active site directed electrophile or a suicide substrate. Nevertheless, the GlAD active site poses challenging requirements for successful lead-inhibitor design. Firstly, because the ionization of the catalytic Cys-thiol is substrate assisted, the inhibitor must likewise induce Cys-thiol ionization. Secondly, because the substrate-binding is based on multiple polar interactions (which includes ion pair formation) within a spatially confined binding site, the inhibitor must also possess strategically placed, and sized, polar substituents.

Acknowledgements

The pDEST-MBP vector was a generous gift from Dr. D. S. Waugh and the Nω-Amino-L-citrulline was a gift from Dr. S. Bruce King.

Abbreviations

- AD

arginine deiminase

- GMSF

guanidino-group modifying enzyme superfamily

- IPTG

isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- NADH

the reduced form of nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- Bis-Tris

[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]tris-(hydroxymethyl)methane

- HEPES

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)-piperazine-N’-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- Tris

tris(hydroxymethyl) aminomethane

- TAPS

3-[[tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]amino]propanesulfonic acid

- CHES

2-(N-cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid

- CAPS

3-(cyclohexylamino)-propanesulfonic acid

- GlAD

Giardia lamblia arginine deiminase

- PaAD

Pseudomonas aeruginosa arginine deiminase

- EcAD

Escherichia coli arginine deiminase

- BmAD

Burkholderia mallei arginine deiminase

- BcAD

Bacillus cereus arginine deiminase

- PAD

peptidylarginine deiminase

- AgD

agmatine deiminase

- DDAH

Nω, Nω-dimethylarginine dimethylamidohydrolase

- PaDDAH

Pseudomonas aeruginosa Nω, Nω-dimethylarginine dimethylamidohydrolase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supported by NIH grant AI059733 to O.H., P.S.M and D. D.-M.

References

- 1.Zuniga M, Perez G, Gonzalez-Candelas F. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2002;25:429–444. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(02)00277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunin R, Glansdorff N, Pierard A, Stalon V. Microbiol. Rev. 1986;50:314–352. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.3.314-352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirai H, Blundell TL, Mizuguchi K. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001;26:465–468. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01906-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakada Y, Itoh Y. Microbiology. 2003;149(Pt 3):707–714. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llacer JL, Polo LM, Tavarez S, Alarcon B, Hilario R, Rubio V. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:1254–1265. doi: 10.1128/JB.01216-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu X, Li L, Wu R, Feng X, Li Z, Yang H, Wang C, Guo H, Galkin A, Herzberg O, Mariano PS, Martin BM, Dunaway-Mariano D. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1162–1172. doi: 10.1021/bi051591e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galkin A, Lu X, Dunaway-Mariano D, Herzberg O. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:34080–34087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505471200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das K, Butler GH, Kwiatkowski V, Clark AD, Jr, Yadav P, Arnold E. Structure. 2004;12:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray-Rust J, Leiper J, McAlister M, Phelan J, Tilley S, Santa Maria J, Vallance P, McDonald N. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001;8:679–683. doi: 10.1038/90387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone EM, Person MD, Costello NJ, Fast W. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7069–7078. doi: 10.1021/bi047407r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arita K, Hashimoto H, Shimizu T, Nakashima K, Yamada M, Sato M. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:777–783. doi: 10.1038/nsmb799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knodler LA, Schofield PJ, Gooley AA, Edwards MR. Exp. Parasitol. 1997;85:77–80. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adam RD. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14:447–475. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.447-475.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Touz MC, Ropolo AS, Rivero MR, Vranych CV, Conrad JT, Svard SG, Nash TE. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:2930–2938. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palm JE, Weiland ME, Griffiths WJ, Ljungstrom I, Svard SG. J. Infect. Dis. 2003;187:1849–1859. doi: 10.1086/375356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ringqvist E, Palm JE, Skarin H, Hehl AB, Weiland M, Davids BJ, Reiner DS, Griffiths WJ, Eckmann L, Gillin FD, Svard SG. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2008;159:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Li Z, Wang C, Xu D, Mariano PS, Guo H, Dunaway-Mariano D. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4721–4732. doi: 10.1021/bi7023496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stamler JS, Feelisch M. Methods in Nitric Oxide Research. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1996. pp. 521–539. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wagenaar FL, Kerwin JF. J. Org. Chem. 1993;58:4331–4338. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keister DB. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1983;77:487–488. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(83)90120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nallamsetty S, Austin BP, Penrose KJ, Waugh DS. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2964–2971. doi: 10.1110/ps.051718605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Touz M, Kulakova T, Nash TE. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:3053–3060. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-10-0744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prescott LM, Jones ME. Anal. Biochem. 1969;32:408–419. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(69)80008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weickmann JL, Fahrney DE. J. Biol. Chem. 1977;252:2615–2620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barshop BA, Wrenn RF, Frieden C. Anal. Biochem. 1983;130:134–145. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bates PA, Kelley LA, MacCallum RM, Sternberg MJ. Proteins Suppl. 2001;5:39–46. doi: 10.1002/prot.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galkin A, Kulakova L, Melamud E, Li L, Wu C, Mariano P, Dunaway-Mariano D, Nash TE, Herzberg O. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:4859–4867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609534200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knodler LA, Sekyere EO, Stewart TS, Schofield PJ, Edwards MR. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:4470–4477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galkin A, Kulakova L, Sarikaya E, Lim K, Howard A, Herzberg O. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:14001–14008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Li Z, Chen D, Lu X, Feng X, Wright EC, Solberg NO, Dunaway-Mariano D, Mariano PS, Galkin A, Kulakova L, Herzberg O, Green-Church KB, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;30:1918–1931. doi: 10.1021/ja0760877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu X, Galkin A, Herzberg O, Dunaway-Mariano D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5374–5375. doi: 10.1021/ja049543p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kearney PL, Bhatia M, Jones NG, Yuan L, Glascock MC, Catchings KL, Yamada M, Thompson PR. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10570–10582. doi: 10.1021/bi050292m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibatani T, Kakimoto T, Chibata I. J. Biol. Chem. 1975;250:4580–4583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith DW, Ganaway RL, Fahrney DE. J. Biol. Chem. 1978;253:6016–6020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong L, Fast W. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:34684–34692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707231200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knipp M, Braun O, Vasak M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2372–2373. doi: 10.1021/ja0430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun O, Knipp M, Chesnov S, Vasak M. Protein Sci. 2007;16:1522–1534. doi: 10.1110/ps.062718507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frey D, Braun O, Briand C, Vasak M, Grutter MG. Structure. 2006;14:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brisson JR, Carey PR, Storer AC. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:9087–9089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang TC, Abeles RH. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1987;252:626–634. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dufour E, Storer AC, Menard R. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9136–9143. doi: 10.1021/bi00028a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddy SY, Kahn K, Zheng YJ, Bruice TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12979–12990. doi: 10.1021/ja020918l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]