Abstract

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4) is recognised as an attractive anti-diabetic drug target, and several DPP4 inhibitors are already on the market. As members of the same gene family, dipeptidyl peptidase 8 (DPP8) and dipeptidyl peptidase 9 (DPP9) share high sequence and structural homology as well as functional activity with DPP4. However, the inhibition of their activities was reported to cause severe toxicities. Thus, the development of DPP4 inhibitors that do not have DPP8 and DPP9 inhibitory activity is critical for safe anti-diabetic therapy. To achieve this goal, we established a selective evaluation method for DPP4 inhibitors based on recombinant human DPP8 and DPP9 proteins expressed by Rosetta cells. In this method, we used purified recombinant 120 kDa DPP8 or DPP9 protein from the Rosetta expression system. The optimum concentrations of the recombinant DPP8 and DPP9 proteins were 30 ng/mL and 20 ng/mL, respectively, and the corresponding concentrations of their substrates were both 0.2 mmol/L. This method was highly reproducible and reliable for the evaluation of the DPP8 and DPP9 selectivity for DPP4 inhibitor candidates, which would provide valuable guidance in the development of safe DPP4 inhibitors.

Key words: DPP4, DPP8, DPP9, Inhibitor, Selective evaluation method

Graphical abstract

A highly reproducible and selective method to evaluate the DPP8 and DPP9 selectivity for DPP4 inhibitor candidates based on recombinant human DPP8 and DPP9 proteins expressed by Rosetta cells was established, which would provide valuable guidance in the development of safe DPP4 inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Dipeptidyl peptidase 8 (DPP8) and dipeptidyl peptidase 9 (DPP9) belong to the S9b gene family (also called the ‘DPP4 gene family’), which share sequence homology, a similar tertiary structure and functional activity with dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4)1. Considering the post-proline dipeptidyl aminopeptidase activity of the S9b gene family, various neuropeptides, chemokines, and peptide hormones can be their natural substrates and be involved in their protein degradation2. Therefore, many of these enzymes have been found to be effective drug targets. For example, DPP4 is a target of type 2 diabetes. By extending the half-life of endogenous glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), DPP4 inhibitors can induce insulin secretion, lower blood glucose and HbA1C levels, reduce the apoptosis and improve the proliferation of β cells. Five DPP4 inhibitors, sitagliptin, valdagliptin, saxaglptin, alogliptin and linagliptin, have been on the market3.

The safety or side effects of DPP4 inhibitors are the key points of consideration during drug discovery, mainly due to the similarity of DPP8/9 with DPP4. The amino acid sequences of DPP8 and DPP9 are highly identical to DPP44,5. All three proteins also share similar structures, consisting of an N-terminal, eight-bladed β-propeller, C-terminal α/β hydrolase domain6, a catalytic triad (Ser–Asp–His) and a conserved Glu motif (Glu–Glu)7. Currently, little is known about the endogenous substrates and biological functions of DPP8 and DPP9, but some studies have indicated that selective DPP8 and DPP9 inhibitors may cause severe toxicities, such as thrombocytopenia, alopecia, reticulocytopoenia, enlarged lymph nodes, splenomegaly, multiorgan histopathological changes and mortality in rats and gastrointestinal toxicity in dogs. Inhibition of DPP8 and DPP9 activities may attenuate T cells activation and proliferation in vitro8. So without DPP8 and DPP9 inhibitory activity is very important to the development of a DPP4 inhibitor as an anti-diabetic agent.

This study was to establish an evaluation method based on recombinant human DPP8 and DPP9 proteins to detect the selectivity of DPP4 inhibitor candidates, which would provide valuable guidance in the development of safe DPP4 inhibitors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

The recognised dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) substrate Gly-Pro-p-nitroanilide and DPP4 enzyme were purchased from Sigma (Missouri, USA). The VigoScript first strand cDNA synthesis kit was a product of Vigorous (Beijing, China). Rosetta competent cells were obtained from TransGen (Beijing, China). Restriction enzymes were purchased from Takara (Dalian, China). Nickel affinity columns, Trizol reagent and DNA polymerase were obtained from Invitrogen (Shanghai, China). The plasmid vector pET32-a(+) was a product of Novagen (Shanghai, China). The anti-His antibody was purchased from Abmart (Shanghai, China). The DPP inhibitor compounds, sitagliptin and UAMC00132 were provided by Prof. Haihong Huang.

2.2. Cloning and construction of recombinant DPP8 and DPP9

The full-length fragments of human DPP8 and DPP9 were obtained via reverse-transcription (RT)–PCR technology from HeLa and HepG2 cells, respectively. Primers for human DPP8 (GenBank ID: AF221634; DPP8-Forward-Hind III 5′-ATCAAGCTTGCCACCATGGCAGCAGCAATG-3′ and DPP8-Reverse-Sal I 5′-ATCGTCGACTTATATCACTTTTAGAGCAGCAATACG-3′) and DPP9 (GenBank ID: AF374518; DPP9-Forward-BamH I 5′-ATCGGATCCGCCACCATGGGGAAGGTTAAG-3′ and DPP9-Reverse-Xho I 5′-ATCCTCGAGTCAGAGGTATTCCTGTAGAAAGTGCAG-3′) were designed with restriction enzyme sites for directional cloning. The PCR was performed as follows: DNA denaturation at 94 °C for 10 min, then 35 cycles (94 °C for 10 s, 65.8 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 3 min) and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The Hind III/Sal I fragment of DPP8 was subcloned into the Hind III and Xho I digested pET32-a(+) expression vector, generating plasmid pET32-a(+)–DPP8. Meanwhile, the BamH I/Xho I fragment of DPP9 was subcloned into the BamH I and Xho I digested pET32-a(+) expression vector, generating plasmid pET32-a(+)–DPP9. Finally, their sequences were verified. pET32-a(+)–DPP8 and pET32-a(+)–DPP9 were expected to express recombinant DPP8 and DPP9 proteins containing 882 and 892 amino acids, respectively, with additional His6, S and Trx tags in the N-terminus.

2.3. Prokaryotic expression, protein purification and Western blot

Rosetta competent cells transformed with the pET32-a(+)–DPP8 plasmid were cultured in LB medium containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C. Protein expression was induced by isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (1 mmol/L) at 16 °C for 20 h, until the OD600 value of the LB medium reached 0.6. The cells were harvested at 6000 rpm for 5 min and incubated in lysozyme buffer (2 mg/mL lysozyme, 100 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 100 mmol/L NaCl) for 40 min on ice. This was followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min and filtration through a 0.45 μm filter. The filtrate was purified with a nickel affinity column as follow: the column was equilibrated with binding buffer (20 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 10 mmol/L imidazole, 0.5 mol/L NaCl), and then the supernatant was passed through the column. Subsequently, binding buffer was used to wash the column, followed by elution buffer (20 mmol/L Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 500 mmol/L imidazole, 0.5 mol/L NaCl). All procedures were done at 4 °C. The enzyme activities of the eluted fractions were monitored, and the active fractions were pooled and analysed using sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot. The expression and purification procedures of DPP9 were the same as DPP8.

2.4. Determination of the optimum concentrations of the substrate and purified recombinant proteins

To determine the optimum concentrations of the substrate and purified recombinant proteins, the assay was performed with different concentrations of DPP8 or DPP9 protein (0–60 ng/mL) and a concentration range of Gly-Pro-p-nitroanilide (0–0.5 mmol/L) in HEPES buffer (pH 7.05) in a final volume of 100 µL. The change in absorbance at 405 nm was kinetically monitored every 10 min for 120 min at 37 °C.

2.5. DPP selectivity evaluation based on DPP8/9 and DPP4 inhibitor screening method

2.5.1. DPP selectivity evaluation based on DPP8/9 inhibition assays

For the practicality and applicability of the inhibition assays, the proven DPP4 inhibition assay was referenced, which indicated the changes of OD values were 0.1–0.2 in 60 min. According to the optimised concentration detection results described above, the final concentrations of test compounds and Gly-Pro-p-nitroanilide were chosen to be 10 μmol/L and 0.2 mmol/L, respectively; and the concentrations of DPP8 and DPP9 were 30 ng/mL and 20 ng/mL, respectively. The change in absorbance at 405 nm was monitored for 60 min at 37 °C. Distilled water was used as a negative control. The percentage of inhibition was calculated as shown below.

Inhibition (%)=(ΔOD60-0 of control−ΔOD60-0 of test)/ΔOD60-0 of control×100%

2.5.2. The screening method of DPP4 inhibitor

The test well contained 10 µL compound solution (diluted to the concentration of 10 µmol/L) and 50 µL DPP4 solution (2 mU/mL in 50 mmol/L Tris–HCl buffer, pH 8.0) in a 96-well plate. The enzyme reaction was started by addition of 40 µL Gly-Pro-p-nitroanilide solution (0.26 mmol/L, in HEPES buffer, pH 7.05). The change in absorbance at 405 nm was monitored for 60 min at 37 °C. Compound solution was replaced by the distilled water in the negative control well. The percent of inhibition was calculated as above.

Two different DPP inhibitors, sitagliptin and UAMC00132, were used to confirm the specific inhibition of DPP8/9 and DPP4.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All values were presented as mean±S.E.M. The Sigma Plot software was used for data analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of prokaryotic DPP8/9 expression plasmids

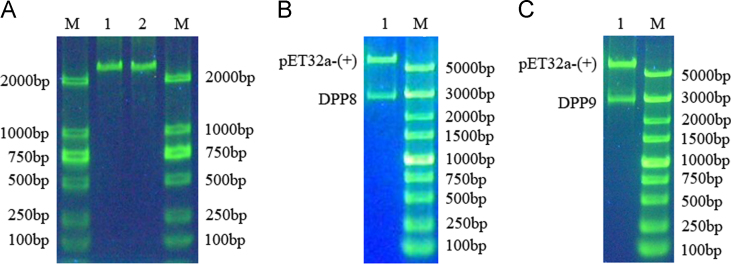

Using RT-PCR, we obtained 2649 bp and 2679 bp fragments of DPP8 and DPP9, respectively, with extra primer bases (Fig. 1A). Using the additional restriction sites, the DNA fragments were successfully inserted into the pET32-a(+) (~5,900 bp) plasmid and identified by restriction digestion (Fig. 1B and C) and sequencing.

Figure 1.

Identification of the recombinant plasmids by restriction digestion. (A) RT-PCR of human DPP8 and DPP9. M: DNA marker; Line 1: DPP8; Line 2: DPP9. (B) Identification of the recombinant pET32-a(+)–DPP8 plasmid. M: DNA marker; Line 1: pET32-a(+)–DPP8 plasmid. (C) Identification of the recombinant pET32-a(+)–DPP9 plasmid. M: DNA marker; Line 1: pET32-a(+)–DPP9 plasmid.

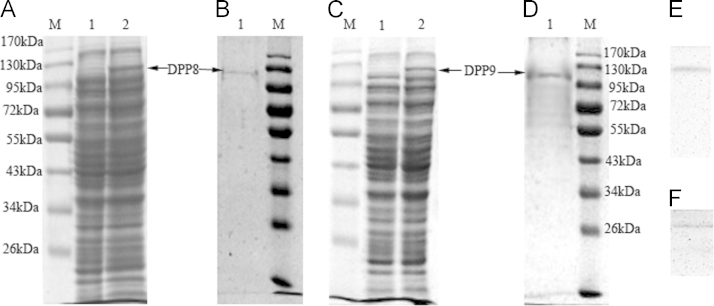

3.2. Protein expression, purification and identification

The recombinant human DPP8 and DPP9 proteins were successfully expressed in the Rosetta cells induced by IPTG (1 mmol/L) and analysed by SDS-PAGE. The corresponding bands of DPP8 and DPP9 were both at approximately 120 kDa (Fig. 2A and C). The recombinant DPP8 and DPP9 proteins with His6-tags were purified on a nickel affinity column and then dissolved in the neutral Tris buffer. The soluble, purified target proteins were also approximately 120 kDa (Fig. 2B and D), which was confirmed by Western blot analysis using an anti-His antibody (Fig. 2E and F).

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analyses of recombinant DPP8 and DPP9 proteins. (A) Expression of DPP8 protein. M: protein marker; Line 1: negative control without induction by IPTG; Line 2: the expression of recombinant DPP8 protein induced by IPTG; (B) Purification of DPP8 protein. M: protein marker; Line 1: recombinant DPP8 protein purified using a nickel affinity column. (C) Expression of DPP9 protein. M: protein marker; Line 1: negative control without induction by IPTG; Line 2: the expression of recombinant DPP9 protein induced by IPTG; (D) Purification of DPP9 protein. M: protein marker; Line 1: recombinant DPP9 protein purified using a nickel affinity column. (E) Western blot analysis of purified DPP8 protein using an anti-His antibody. (F) Western blot analysis of purified DPP9 protein using an anti-His antibody. The arrow marks the corresponding recombinant protein at approximately 120 kDa.

3.3. Determination of the optimum concentrations of DPP8/9 and substrate in a direct enzyme inhibition assay

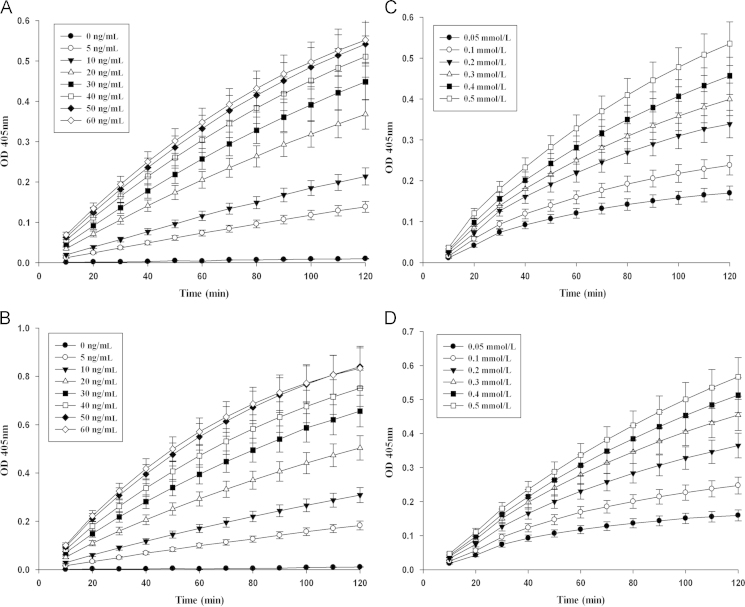

The recombinant human DPP8 and DPP9 proteins were found to display specific dipeptidyl peptidase activities similar to DPP4, but the enzyme kinetic characteristics were unknown. By monitoring the increasing absorbance rate at 405 nm, concentration-activity experiments of recombinant DPP8/9 were performed. The experiment showed that the reactivity of recombinant DPP9 was higher than DPP8. To determine the reliable and practical reaction conditions that were suitable for the soluble DPP8 and DPP9 activity inhibition assay, the proven DPP4 inhibition assay was referenced, which indicated the changes of OD values were 0.1–0.2 in 60 min. The experiment indicated that the optimum concentrations of the purified recombinant DPP8 and DPP9 proteins were 30 ng/mL and 20 ng/mL for 60 min, respectively, with 0.5 mmol/L substrate (Fig. 3A and B), and the optimum substrate concentration for both DPP8 (30 ng/mL) and DPP9 (20 ng/mL) was 0.2 mmol/L (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Determination of the optimum concentrations of the purified recombinant DPP8/9 protein and substrate. The purified recombinant DPP8 (A) and DPP9 (B) proteins, with a range of concentrations from 0 to 60 ng/mL and 0.5 mmol/L substrate; The substrate with different concentrations, from 0.05 to 0.5 mmol/L at 30 ng/mL DPP8 (C) and 20 ng/mL DPP9 (D).

3.4. DPP inhibition selectivity evaluation based on a direct DPP8/9 and DPP4 enzyme inhibition assay

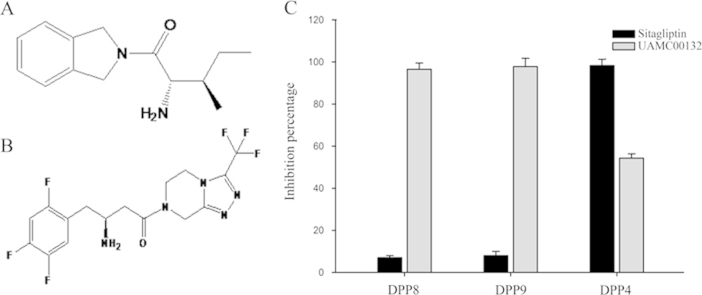

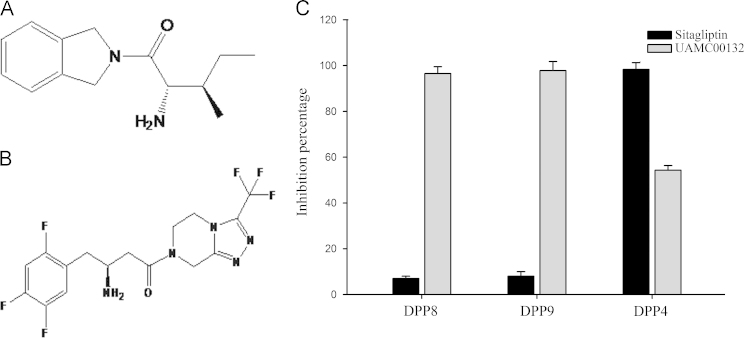

Using the recombinant DPP8/9 activity assay with the above optimised reaction conditions and the DPP4 activity assay method, the effects of two reported DPP inhibitors on DPP8/9 and DPP4 activities were determined. DPP8/9 inhibitor UAMC00132 (10 μmol/L) could, while DPP4 inhibitor sitagliptin (10 μmol/L) could not, inhibit DPP8 and DPP9 activities. Meanwhile, sitagliptin strongly inhibited DPP4 activity strongly, while UAMC00132 only slightly inhibited DPP4 activity (Fig. 4), which indicated that the selective evaluation method was established to evaluate the DPP8 and DPP9 selectivity of DPP4 inhibitor candidates.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of recombinant DPP8/9 and DPP4 activities by UAMC00132 and Sitagliptin. Chemical structure of UAMC00132 (A) and sitagliptin (B). (C) The DPP8/9 and DPP4 inhibitory activities of sitagliptin and UAMC00132. In DPP8/9 inhibition assays, 30 ng/mL purified DPP8 protein or 20 ng/mL purified DPP9 protein and 0.2 mmol/L substrate were used, and in DPP4 inhibition assay, 1 mU/mL DPP4 protein and 0.1 mmol/L substrate were used. The result was presented as the percentage of enzyme activity inhibition.

4. Discussion

The two DPP4 homologues, DPP8 and DPP9, were identified in the years 20004 and 20025. Especially Lankas et al.8 found that the inhibition of DPP8 and DPP9 activities could cause severe toxicities. Since then, DPP8 and DPP9 have become popular issues, and a great deal of attentions have been focused on the genes, substrates, inhibitors, structures and functions of these peptidases. In this study, we established a selective evaluation method of DPP4 inhibitors based on the recombinant human DPP8 and DPP9 proteins, which would facilitate and accelerate finding potent and highly selective DPP4 inhibitors.

We used Rosetta cells to express the full length 882 amino acid DPP8 (DPP8882aa) and 892 amino acid DPP9 (DPP9892aa) proteins with additional His6, S and Trx tags in the N-terminus and with or without another His6-tag in the C-terminus. In these recombinant variants, we found that only the full length DPP8 and DPP9 proteins without the C-terminus His6-tag had enzymatic activities, which was consistent with a report by Bjelke9. Some reports showed that the purified recombinant DPP8 and DPP9 proteins were monomeric when C-terminus tags were present, but when tags were in the N-terminus, the protein could be dimeric4,7,9. As dimerisation was shown to be essential for the peptidase activity, we considered that the C-terminus His6-tag of recombinant DPP8/9 may prevent dimerisation and cause a loss of activity. Conversely, other studies have reported active DPP9 with a C-terminus His6-tag expressing in a eukaryotic system, such as Pichia pastoris and Spodoptera frugiperda 9 (Sf9) cells, and assumed that the presence of post-translational modifications in mammalian cells may influence the activity of recombinant DPP910–14. In this study, active recombinant DPP8/9 with an N-terminal His6-tag, first expressing in a prokaryotic system, showed practical and suitable activity for use in a DPP inhibitor assay.

The Glu–Glu motif in DPP4 (Glu205–Glu206) was also present in DPP8 (Glu256–Glu257) and DPP9 (Glu277–Glu278), which was very important to the peptidase activity and substrate entry, and any mutation in this motif would abolish the peptidase activity7,15. Some reports also suggested that the α/β hydrolase domains in both the N- and C-terminus of DPP8 and DPP9 proteins were pivotal to the enzymatic activity and to maintain an intact structure and removing these domains would abolish the enzymatic activity7. We also expressed the truncated Δ659–882 amino acid of DPP8 (DPP8Δ659–882aa) with additional His6, S and Trx tags in the N-terminus. We further confirmed that the lack of the Glu–Glu motif and the α/β hydrolase domain of the N-terminus completely abolished enzymatic activity, even though DPP8Δ659–882aa contained the catalytic domain.

In summary, we had established a selective evaluation method for DPP4 inhibitor candidates based on the recombinant human DPP8 and DPP9 proteins. This method was highly reproducible and reliable and would provide valuable guidance in the development of promising selective and safe DPP4 inhibitors. We had used the method to evaluate a number of DPP4 inhibitor candidates.

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate Prof. Haihong Huang and Dr. Bei Han for the chemical synthesis of UAMC00132 and sitagliptin. This work was supported by a fund from National Mega-project for Innovative Drugs (2012ZX09301002-004, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Rosenblum J., Kozarich J.W. Prolyl peptidases: a serine protease subfamily with high potential for drug discovery. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:496–504. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y.S., Chien C.H., Goparaju C.M., Hsu J.T., Liang P.H., Chen X. Purification and characterization of human prolyl dipeptidase DPP8 in Sf9 insect cells. Protein Expr Purif. 2004;35:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deacon C.F. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a comparative review. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbott C.A., Yu D.M., Woollatt E., Sutherland G.R., Mccaughan G.W., Gorrell M.D. Cloning, expression and chromosomal localization of a novel human dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP) IV homolog, DPP8. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:6140–6150. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen C., Wagtmann N. Identification and characterization of human DPP9, a novel homologue of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Gene. 2002;299:185–193. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott C.A., Yu D.M., McCaughan G.W., Gorrell M.D. Postproline-cleaving peptidases having DP IV like enzyme activity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;477:103–109. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46826-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajami K., Abbott C.A., Obradovic M., Gysbers V., Kahne T., McCaughan G.W. Structural requirements for catalysis, expression, and dimerization in the CD26/DPIV gene family. Biochemistry. 2003;42:694–701. doi: 10.1021/bi026846s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lankas G.R., Leiting B., Roy R.S., Eiermann G.J., Beconi M.G., Biftu T. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: potential importance of selectivity over dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9. Diabetes. 2005;54:2988–2994. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.10.2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bjelke J.R., Christensen J., Nielsen P.F., Branner S., Kanstrup A.B., Wagtmann N. Dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9: specificity and molecular characterization compared with dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J Biochem. 2006;396:391–399. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajami K., Abbott C.A., McCaughan G.W., Gorrell M.D. Dipeptidyl peptidase 9 has two forms, a broad tissue distribution, cytoplasmic localization and DPIV-like peptidase activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1679:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burkey B.F., Hoffmann P.K., Hassiepen U., Trappe J., Juedes M., Foley J.E. Adverse effects of dipeptidyl peptidases 8 and 9 inhibition in rodents revisited. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:1057–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee H.J., Chen Y.S., Chou C.Y., Chien C.H., Lin C.H., Chang G.G. Investigation of the dimer interface and substrate specificity of prolyl dipeptidase DPP8. J Bio Chem. 2006;281:38653–38662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi S.Y., Riviere P.J., Trojnar J., Junien J.L., Akinsanya K.O. Cloning and characterization of dipeptidyl peptidase 10, a new member of an emerging subgroup of serine proteases. J Biochem. 2003;373:179–189. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajami K., Pitman M.R., Wilson C.H., Paek J., Menz R.I., Starr E.A. Stromal cell-derived factors 1α and 1β, inflammatory protein-10 and interferon-inducible T cell chemo-attractant are novel substrates of dipeptidyl peptidase 8. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbott C.A., McCaughan G.W., Gorrell M.D. Two highly conserved glutamic acid residues in the predicted L propeller domain of dipeptidyl peptidase IV are required for its enzyme activity. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:278–284. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01166-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]