Abstract

The glomerulus is a highly specialized capillary tuft, which under pressure filters large amounts of water and small solutes into the urinary space, while retaining albumin and large proteins. The glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) is a highly specialized filtration interface between blood and urine that is highly permeable to small and midsized solutes in plasma but relatively impermeable to macromolecules such as albumin. The integrity of the GFB is maintained by molecular interplay between its 3 layers: the glomerular endothelium, the glomerular basement membrane and podocytes, which are highly specialized postmitotic pericytes forming the outer part of the GFB. Abnormalities of glomerular ultrafiltration lead to the loss of proteins in urine and progressive renal insufficiency, underlining the importance of the GFB. Indeed, albuminuria is strongly predictive of the course of chronic nephropathies especially that of diabetic nephropathy (DN), a leading cause of renal insufficiency. We found that high glucose concentrations promote autophagy flux in podocyte cultures and that the abundance of LC3B II in podocytes is high in diabetic mice. Deletion of Atg5 specifically in podocytes resulted in accelerated diabetes-induced podocytopathy with a leaky GFB and glomerulosclerosis. Strikingly, genetic alteration of autophagy on the other side of the GFB involving the endothelial-specific deletion of Atg5 also resulted in capillary rarefaction and accelerated DN. Thus autophagy is a key protective mechanism on both cellular layers of the GFB suggesting autophagy as a promising new therapeutic strategy for DN.

Keywords: autophagy, diabetic nephropathy, endothelial cells, podocytes, proteinuria, sclerosis

Abbreviations

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- CASP3

caspase 3, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase

- Cdh5

cadherin 5

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- DN

diabetic nephropathy

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- GBM

glomerular basement membrane

- GEC

glomerular endothelial cells

- GFB

glomerular filtration barrier

- MAP1LC3A/B/LC3A/B)

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 α/β

- MTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin

- Nphs2

nephrosis 2, podocin

- SQSTM1

sequestosome 1

- STZ

streptozotocin

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- TUBA

tubulin

- α

WT1, Wilms tumor 1

Introduction

Glomerular kidney diseases are a major public health issue. Indeed, these diseases are highly prevalent and are a major independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, especially in the context of metabolic syndrome. Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is a serious microvascular complication of diabetes and is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in industrialized countries.1 Next to mesangial extracellular matrix deposition and a thickening of basement membranes, progressive loss of podocytes and microvascular alterations appear to most closely correlate with the functional renal decline in DN.2-4 Progressive and irreversible microvascular damage and loss are observed in the diabetic kidney, and a decrease in the function and density of intrarenal microvessels has been reported in several studies.5-8 Furthermore, progressive podocyte injury, characterized by low microvessel density and number, hypertrophy, and foot process effacement, plays a central role in the development of DN in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.4,9-11 Despite the crucial importance of the kidney, both as therapeutic target and as determinant of the prognosis of patients with DN, little is known about the mechanisms underlying kidney damage associated with diabetes. In particular, few studies have investigated the endogenous factors that slow down or prevent the development of complications. Thus, it is important to better understand the pathogenesis of DN and to identify novel therapeutic target molecules.

Autophagy has recently emerged as an interesting potential novel target for the treatment of nondiabetic glomerular diseases.12,13 Autophagy is a highly regulated lysosomal protein degradation pathway that removes protein aggregates and damaged or excess organelles to maintain intracellular homeostasis and cell integrity.14-16 The formation of autophagosomes depends on several genes including Map1lc3B/LC3B, Becn1/Beclin 1, and other autophagy-related (Atg) genes.14 Dysregulation of autophagy is involved in the pathogenesis of a variety of metabolic and age-related diseases.17-23 The function of autophagy in the kidneys is currently under investigation and it has been shown to have a renoprotective effect in several animal models of aging and acute kidney injury, especially in glomeruli.12,24-26 Importantly, postmitotic podocytes exhibit high levels of basal autophagy as a key regulator of podocyte and glomerular maintenance.13

Additionally, a strong body of evidence supports the role for maintenance of endothelial function in diabetes to limit DN progression involving homeostasis of multiple systems 7,27-30 such as NOS3/eNOS (nitric oxide synthase 3 [endothelial cell]) activity, 31 glycocalyx production, 32,33 EDN/endothelin actions 34-38 and balanced VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) 33,39,40 and ANGPT/angiopoietin systems.41 Endothelial cells may also use autophagy as a coping mechanism to metabolic stress. However, there are currently no data on the role of endothelial autophagy in cardiovascular diseases.

Autophagy is regulated by the major nutrient-sensing pathways, including MTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and SIRT1 (sirtuin 1).14,42-46 Studies suggest that alteration of these nutrient-sensing pathways under diabetic conditions impairs the autophagic stress response, which may exacerbate organelle dysfunction and lead to the development of diabetic nephropathy.24 Autophagy can also be induced by high glucose levels in various cell types, partly through hyperglycemia-mediated reactive oxygen species production, and has protective effects in vitro.47-49 In fact, activation of MTOR was associated with an accelerated glomerular injury of DN- or puromycin models potentially suggesting an involvement of autophagy in these disease models 50,51

Nevertheless, the direct role of autophagy in diabetic nephropathy is not fully understood. Thus, the objective of this study was to investigate the precise involvement of podocyte and endothelial autophagy in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy in vivo.

Results

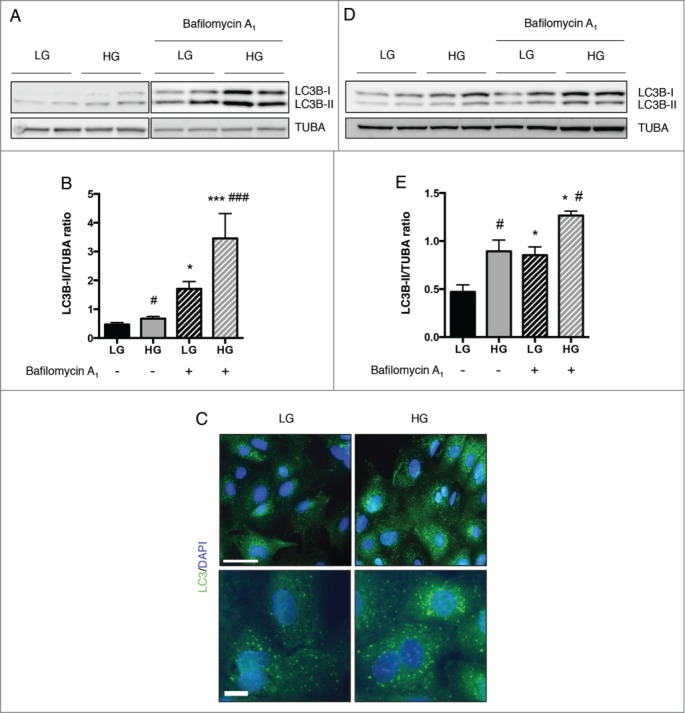

High glucose concentrations induce autophagy in primary podocytes in vitro

We first analyzed the effect of high glucose concentration on podocyte autophagy using a podocyte primary culture. Purity was verified by western blot and immunofluorescence analysis (Fig. S1A, B). Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3A/B (LC3A/B) was used as a marker of autophagy. LC3 is a soluble protein that is proteolytically modified by a C-terminal cleavage to generate a form (LC3-I) that is subsequently conjugated to phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to produce LC3–PE (or LC3-II), which is recruited to phagophore membranes. Meanwhile, the high conversion of LC3-I into LC3-II reflects either a high autophagic flux, or a blockade in autolysosomal degradation.52 Thus, autophagic flux can be measured by inferring LC3 turnover by western blot in the presence or absence of lysosomal degradation. The difference between the amount of LC3-II in the presence or absence of lysosomal inhibitors will allow to determine if the autophagic flux is increased or blocked; indeed, if the flux is occurring, the amount of LC3-II will be higher in the presence of the inhibitor. 53,54 The ratio of LC3B-II/α-tubulin (TUBA) was higher in primary podocytes treated for 24 h with high glucose concentrations (33 mM) than those treated with physiological glucose concentrations (5 mM), suggesting that hyperglycemia induces autophagy in primary podocytes (Fig. 1A, B). Addition of bafilomycin A1 (10 nM), which blocks lysosome acidification and prevents autophagosome degradation, further confirmed the accumulation of LC3B-II elicited by a high glucose concentration (Fig. 1A, B). We also isolated podocytes from GFP-LC3 mice and analyzed LC3 expression in cells treated for 24 h with low or high glucose concentrations. The number of GFP-LC3 puncta (LC3–PE associated with autophagosome membranes) was higher in podocytes treated with a high glucose concentration than in those treated with a low glucose concentration, thus confirming that high glucose induces autophagy in podocytes (Fig. 1C). We then analyzed the effect of hyperglycemia on SVI cells, a stable podocyte cell line, and found that high-glucose treatment for 48 h induces autophagy in SVI cells (Fig. 1D, E), thus confirming short-term effect of high-glucose as an inducer of autophagy in podocytes. On the other hand, LC3B-II expression was reduced in SVI podocytes when treated with high glucose for 15 days, thus showing a long-term repressive effect of high glucose on podocyte autophagy (Fig. S2). We also confirmed that hyperglycemia induces autophagy in glomeruli in vivo, and particularly in podocytes, by examining LC3 staining in an induced model of diabetes. Indeed, LC3 staining in podocytes was stronger in GFP-LC3 mice at 4 wk post-STZ injection, when mice were hyperglycemic but had not developed glomerular lesions, than in GFP-LC3 control mice. LC3 staining was also stronger at 4 wk post-STZ injection than at 1 wk post-STZ injection (Fig. S3A). At 8 wk post-STZ injection, when mice exhibited glomerular lesions, LC3 staining was decreased, supporting the hypothesis of a short-term induction followed by a long-term repression of the autophagic flux in glomeruli under hyperglycemia stimuli (Fig. S3A). To confirm that increased LC3 expression represents increased autophagic flux, we treated mice with chloroquine (50 mg/kg) for 4 d before sacrifice, in order to block lysosomal acidification and consequently autolysosome degradation. Western blot analysis revealed LC3B-II accumulation in glomeruli from mice at 4 wk post-STZ injection treated with chloroquine compared to control mice treated with chloroquine (Fig. S3B), thus confirming hyperglycemia-induced autophagic flux in glomeruli at 4 wk post-STZ injection. Finally, we also analyzed SQSTM1/p62 expression in glomeruli. We found that SQSTM1 almost exclusively colocalized with LC3 in autophagosomes in glomeruli from control mice and at 4 wk post-STZ injection, while SQSTM1 was accumulated in the cytoplasm of glomerular cells at 8 wk post-STZ injection (Fig. S4). These results confirmed an active autophagic flux in glomeruli in early stage diabetes.

Figure 1.

High glucose concentrations induce autophagy in podocytes. (A) Western blot analysis of the abundance of LC3B in primary podocytes treated with low glucose (LG, 5 mM D-glucose) or high glucose (HG, 33 mM D-glucose) concentrations for 24 h in the absence or presence of bafilomycin A1 (10 nM). (B) Quantification of western blot bands showing LC3B-II normalized to TUBA band intensity. Values are means ± SEM of at least 9 mice. * # P <0.05, *** ### P<0.001, * different conditions of bafilomycin A1 treatment, same glucose concentration, # same conditions of bafilomycin A1 treatment, different glucose concentration. (C) Representative images of the expression of LC3 assessed by immunofluorescence in primary podocytes treated with low glucose (LG, 5 mM D-glucose) or high glucose (HG, 33 mM D-glucose) concentrations for 24 h. Scale bar: 50 μm (upper panel) and 15 μm (lower panel). (D) Western blot analysis of the abundance of LC3B in SVI podocytes treated with low glucose (LG, 5 mM D-glucose) or high glucose (HG, 33 mM D-glucose) concentrations for 48 h in the absence or presence of bafilomycin A1 (100 nM, 4 h). (E) Quantification of western blot bands showing LC3B-II normalized to TUBA band intensity. Values are means ± SEM of 3 experiments. *#P < 0.05, * different conditions of bafilomycin A1 treatment, same glucose concentration, # same conditions of bafilomycin A1treatment, different glucose concentration.

Podocyte-specific Atg5 deficiency results in diabetes-induced podocytopathy, a leaky filtration barrier, and glomerulosclerosis

We sought to define the role of the autophagy pathway specifically in podocytes. We thus generated podocyte-specific Atg5 knockout mice by mating Atg5-floxed mice (Atg5lox/lox) 55 with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the podocin promoter Nphs2 (Table S1).56 We confirmed that Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice had normal kidney function and no glomerular histological lesions until 20 mo of age, as previously reported.13

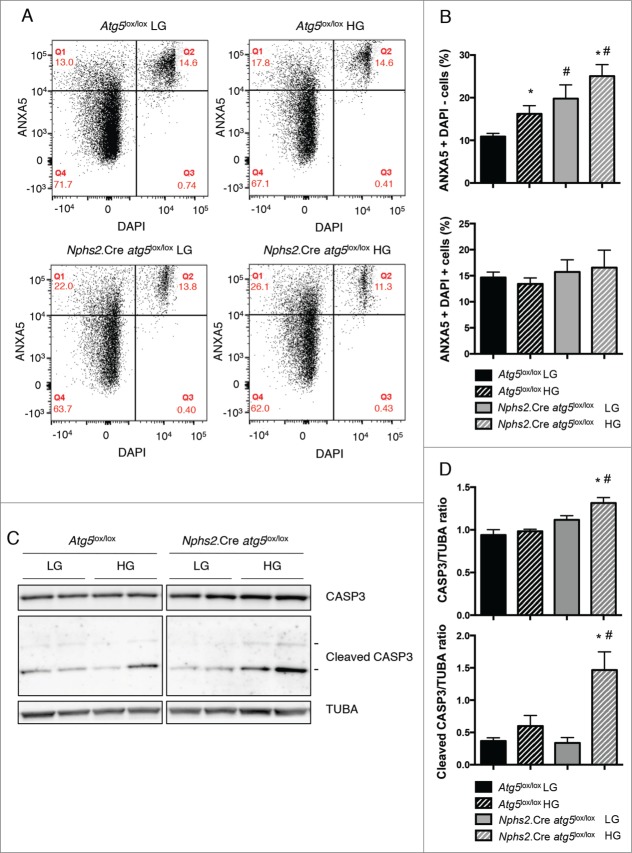

We first analyzed the effect of autophagy deficiency on podocyte cell apoptosis in vitro upon high glucose stimulation. We confirmed the deletion of Atg5 in primary podocytes by western blotting using an anti-ATG5 antibody. Furthermore, primary podocytes from Nphs2.Cre atg5lox/lox mice showed accumulation of LC3-I, SQSTM1, and ubiquitinated proteins, thus confirming efficient autophagy depletion in Atg5-deleted podocytes (Fig. S1C, D). Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that high glucose concentrations induced apoptosis in control primary podocytes (Fig. 2A, B). However, the proportion of apoptotic cells was higher in primary podocytes from Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice than in those from Atg5lox/lox control littermate mice, both at physiological and high glucose concentrations (Fig. 2A, B). We confirmed these results by western blot analysis, which showed a high abundance of cleaved CASP3 in primary podocytes from Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice treated with high glucose concentration (Fig. 2C, D). Thus, this suggests that autophagy protects podocytes from apoptosis induced by high glucose concentrations in vitro.

Figure 2.

For figure legend, see page 1134. Figure 2 (See previous page). Autophagy deficiency promotes apoptosis in podocytes under high glucose concentrations. (A) Representative flow cytometry results for primary podocytes from Atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice after treatment for 48 h with a low glucose (LG, 5 mM D-glucose) or a high glucose (HG, 33 mM D-glucose) concentration. The horizontal axis shows the fluorescence intensity of DAPI and the vertical axis shows that of ANXA5/annexin V-PE. (B) Quantification of the percentage of apoptotic (Q1: ANXA5-positive DAPI-negative) and necrotic (Q2: ANXA5-positive DAPI-positive) cells. Values are means ± SEM of at least 5 mice in 2 independent experiments. * # P <0.05, * same genotype, different glucose concentration, # different genotype, same glucose concentration. (C) Western blot analysis of the abundance of CASP3 and cleaved CASP3 in primary podocytes from Atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice after treatment for 48 h with a low glucose (LG, 5 mM D-glucose) or a high glucose (HG, 33 mM D-glucose) concentration. (D) Quantification of western blot bands showing CASP3 and cleaved CASP3 (17-KDa form) normalized to TUBA band intensity. Values are means ± SEM of 4 mice. * # P<0.05, * same genotype, different glucose concentration, # different genotype, same glucose concentration.

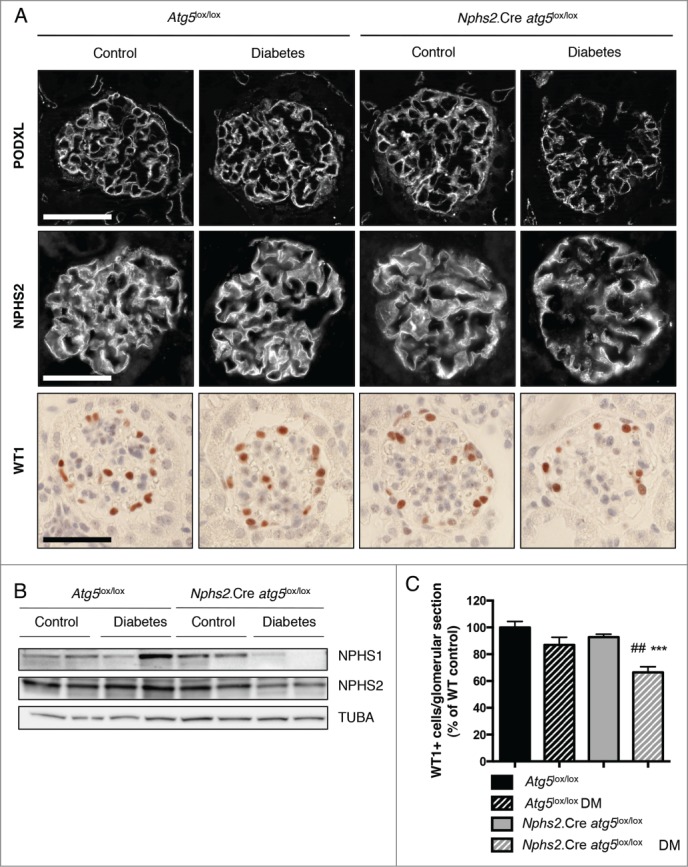

We then examined the role of the autophagy pathway in podocytes after the experimental induction of diabetes mellitus (DM). Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice were made diabetic by streptozotocin (STZ) injection. Ten wk after the induction of diabetes, mice presented typical polyuria and weight loss (data not shown). Diabetic mice developed features of mild DN, as shown by increased kidney-to-body weight ratio, increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels and microalbuminuria (Table 1). Importantly, kidney-to-body weight ratio and BUN levels were higher and microalbuminuria was more severe in Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice than in their control diabetic littermates (Table 1). We next sought to investigate the structure and number of podocytes in diabetic mice. Immunofluorescence showed that the abundance of PODXL/Podocalyxin and the slit diaphragm protein NPHS2 were lower in glomeruli from Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice than in those from nondiabetic Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice, thus demonstrating that podocyte structure is altered in Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice during diabetes. These alterations were specific to the diabetic condition of Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice because the pattern and intensity of PODXL and NPHS2 immunostaining were similar in control diabetic Atg5lox/lox mice and nondiabetic Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice (Fig. 3A). Western blot analysis of NPHS2 and NPHS1/Nephrin expression in isolated glomeruli further confirmed the alteration of podocyte structure in Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice during diabetes (Fig. 3B). We also examined podocyte density by immunohistochemical staining of WT1 (Wilms' tumor 1). The number of podocytes per glomerular section was significantly lower in Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice compared to diabetic and nondiabetic controls, demonstrating the progressive loss of autophagy deficient podocytes in a diabetic environment (Fig. 3A, C). In addition, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses revealed more pronounced glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickening and podocyte foot process broadening and effacement in Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic glomeruli, whereas few ultrastructural defects were found in podocytes from control diabetic mice (Fig. 4).

Table 1.

Nphs2.Cre atg5lox/lox animal phenotype

|

Atg5lox/lox |

Nphs2.Cre atg5lox/lox |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Control (n=11) | Diabetes (n=10) | Control (n=9) | Diabetes (n=15) |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 168.9 ± 12.1 | 484.7 ± 25.7a | 175.7 ± 11.2 | 492.8 ± 32.6a,b |

| Body weight (g) | 30.1 ± 1 | 25.2 ± 1.2a | 29.2 ± 0.9 | 25.1 ± 0.8a,b |

| Kidney to body weight ratio (%) | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 0.77 ± 0.04a | 0.65 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.03a,b,c |

| Urinary ALB to creatinine ratio (mg/mmol) | 0.73 ± 0.12 | 4.17 ± 1.45a | 2.27 ± 0.72 | 16.33 ± 4.86a,b,c |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 18.6 ± 1.3 | 23.9 ± 1.2a | 21.4 ± 0.9 | 29.2 ± 1.9a,b,c |

P < 0.05 vs. Atg5lox/lox control.

P < 0.05 vs. respective non DM.

P < 0.05 vs. Atg5lox/lox control DM.

Figure 3.

Autophagy deficiency specifically in podocytes promotes diabetes-induced podocyte loss. (A) Representative images of the expression of PODXL (upper panel) and NPHS2 (middle panel) by immunofluorescence in 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Representative images of the expression of WT1 (lower panel) by immunohistochemistry in 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Images are representative of at least 6 mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Western blot analysis of NPHS2 and NPHS1 expression in glomerular extracts from 20-week-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Protein concentrations were normalized to TUBA expression. (C) Quantification of the number of WT1-positive cells per glomerular section in 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Data were normalized to Atg5lox/lox control and represent means ± SEM of at least 6 mice. ##P <0.01, *** P<0.001, * same genotype, different treatment, # different genotype, same treatment.

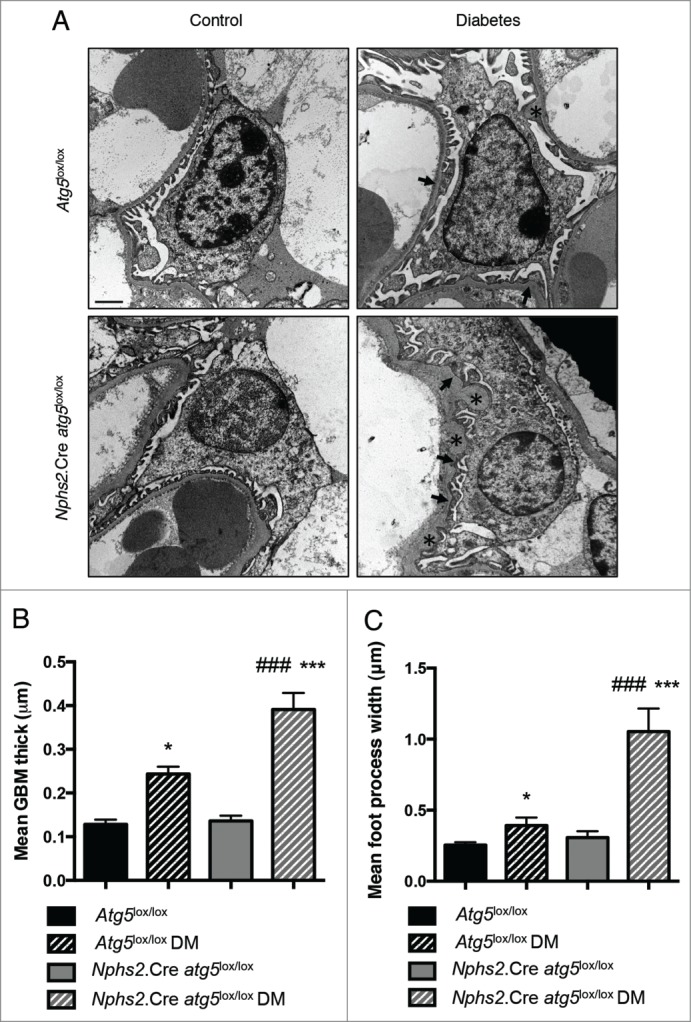

Figure 4.

Autophagy deficiency specifically in podocytes promotes diabetes-induced podocyte ultrastructural alterations. (A) Representative photomicrographs of transmission electron microscopy sections of podocytes from 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice showing GBM thickening (*) and foot process effacement (arrows) in Atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Scale bar: 1 μm. (B, C) Quantifications of mean GBM thickness and mean foot process width in podocytes from 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Data represent means ± SEM of 3 mice. *P <0.05, *** ### P<0.001, * same genotype, different treatment, # different genotype, same treatment.

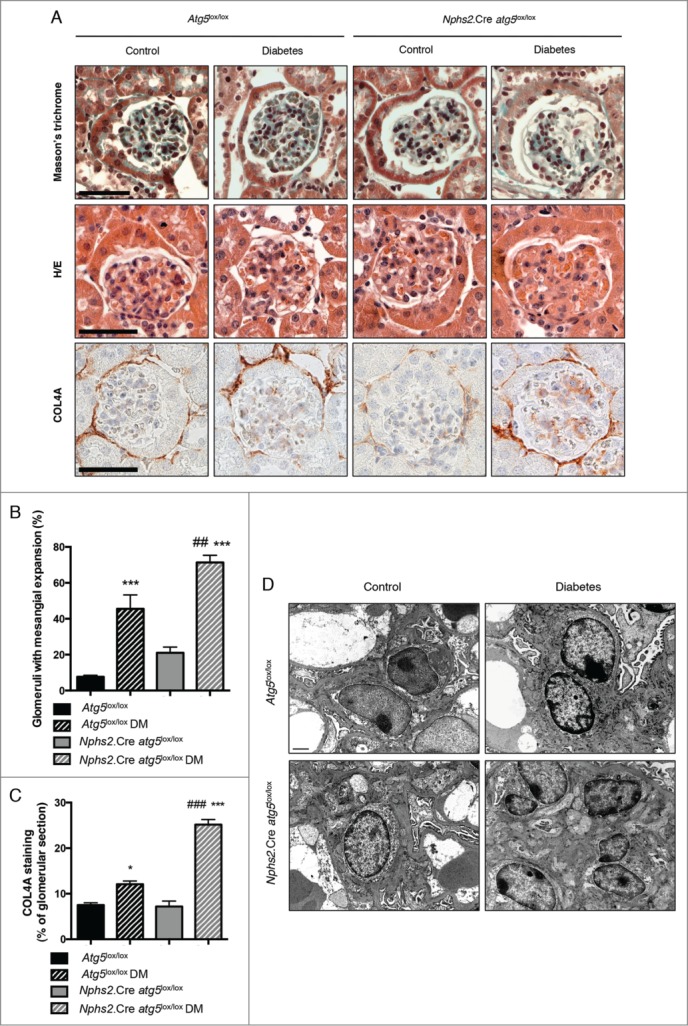

Interestingly, mesangial thickening and glomerulosclerosis was more severe in glomeruli from Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice than in glomeruli from their control diabetic littermates (Fig. 5A, B). Moreover, the deposition of COL4A (collagen, type IV, α) was higher in glomeruli from Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice (Fig. 5A, C). Finally, TEM ultrastructure analyses confirmed that substantial mesangial expansion and glomerular sclerosis was present in Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice only (Fig. 5D). Of note, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice and their control littermates (Atg5lox/lox) were on a pure C57BL6/J genetic background, which is known to be relatively resistant to DN. This may explain why only a small number of glomerular lesions were observed in the control diabetic mice.

Figure 5.

Deletion of Atg5 specifically in podocytes favors diabetes-induced glomerulosclerosis. (A) Representative images of hematoxylin/eosin stained sections (upper panel), Masson trichrome stained sections (middle panel) and COL4A immunohistochemistry (lower panel) of renal cortex from 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Images are representative of at least 6 mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of glomeruli with mesangial expansion in renal cortex from 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Data represent means ± SEM of at least 5 mice. ## P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001, * same genotype, different treatment, # different genotype, same treatment. (C) Quantification of the COL4A staining per glomerular section in 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Data represent means ±SEM of 3 (nondiabetic) or 4 (diabetic) mice. *P < 0.05, ***, ### P < 0.001, * same genotype, different treatment, # different genotype, same treatment. (D) Representative photomicrographs of transmission electron microscopy sections of mesangial cells from 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Scale bar: 1 μm.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that podocyte autophagy exerts protective effects in glomeruli during diabetes mellitus, maintaining podocyte integrity and limiting glomerular sclerosis.

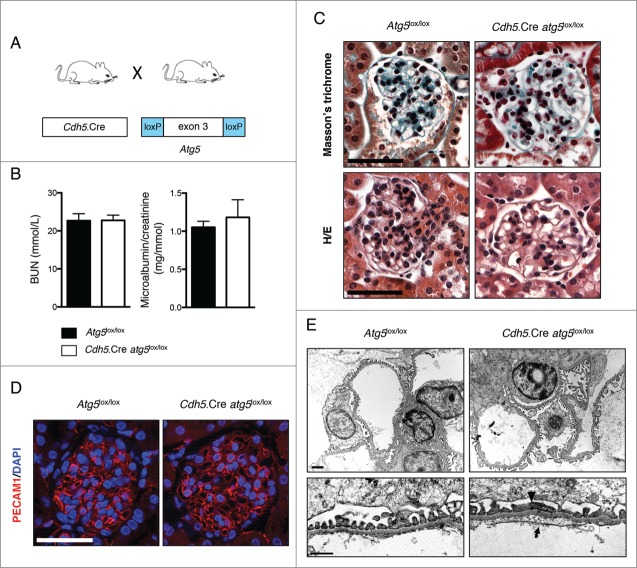

Endothelial-specific Atg5 deficiency results in mild alterations to the GFB at baseline

The maintenance of GFB integrity requires the proper function of podocytes and glomerular endothelial cells, which lie on either side of the GBM. Thus, we next investigated the role of autophagy in endothelial cells in our model. We first generated endothelial-specific Atg5 knockout mice by crossing Atg5-floxed mice (Atg5lox/lox) with the Cdh5.Cre strain (Table S1 and Fig. 6A).57 We also crossed the Cdh5.Cre strain with a ROSA26R-LacZ reporter line (Table S1) and found β-galactosidase staining in most, but not all (around 75%), of the glomerular endothelial cells and in interstitial capillaries in the kidneys of Cdh5.Cre ROSA26R-LacZ mice (Fig. S5A). Furthermore, Cdh5.Cre ROSA26R-Eyfp mice (Table S1) demonstrated costaining between YFP and PECAM1/CD31 (Fig. S5B) and CRE immunofluorescence also confirmed the selective expression of CRE recombinase in endothelial cells of the kidneys of Cdh5.Cre mice including in glomerular capillaries (Fig. S5C). Thus, efficient but not complete, endothelial-selective CRE recombination occurs in glomerular endothelial cells of Cdh5.Cre mice. Cdh5.Cre-Atg5lox/lox mice were born at a Mendelian ratio and were indiscernible from their Atg5lox/lox control littermates regarding weight, size, albuminuria and BUN levels, up to 20 wk of age (Fig. 6B, Table 2 and data not shown). In histological sections, glomeruli from Cdh5.Cre-Atg5lox/lox mice displayed slightly dilated capillaries from 10 wk of age (Figs. 6C, D and 7A, B). The intensity and pattern of PECAM1 immunofluorescence in 10-wk-old Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice was even, showing that capillary dilatation was not associated with marked endothelial defects (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, TEM analyses revealed discrete podocyte foot process effacements and loss of glomerular endothelial fenestrations associated with endothelial cytoplasmic thickening in around 60% of the glomerular capillary loops from Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice (Fig. 6E and Fig. S6A). These data indicate that the deletion of Atg5 specifically in vascular endothelial cells induces mild morphological lesions of the glomerular filtration barrier (GFB), not associated with functional defects of the GFB.

Figure 6.

Endothelial autophagy is not required for kidney development or function. (A) Schematic representation of the generation of mice with autophagy-deficient endothelial cells obtained by mating mice expressing the CRE recombinase under the VE-cadherin promoter (Cdh5.Cre mice) with mice expressing Atg5 alleles with loxP sites flanking exon 3 (Atg5lox/lox mice). (B) Renal function assessed by BUN levels and microalbuminuria/creatinine ratio in 10- to 14-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice. Values are means ± SEM of at least 7 mice. (C) Representative images of Masson trichrome (upper panel) and hematoxylin/eosin (lower panel) stained sections from 10- to 14-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. (D) Representative images of the expression of PECAM1 (red) by immunofluorescence in 10-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI stain (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. (E) Representative photomicrographs of transmission electron microscopy sections of glomeruli from 10-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice showing disappearance of endothelial fenestration (arrow) and podocyte foot process effacements (arrow-head) in Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice. Scale bar: 1 μm (upper panel) and 200 nm (lower panel).

Table 2.

Cdh5.Cre atg5lox/lox animal phenotype

|

Atg5lox/lox |

Cdh5.Cre atg5lox/lox |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Control (n=10) | Diabetes (n=11) | Control (n=10) | Diabetes (n=13) |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 165.3 ± 9.7 | 521.9 ± 30.5a | 150.6 ± 9.8 | 535.5 ± 16.1a,b |

| Body weight (g) | 29.7 ± 0.6 | 26.9 ± 1.3a | 28.2 ± 0.7 | 24.7 ± 0.7a,b |

| Kidney to body weight ratio (%) | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.02a | 0.69 ± 0.03 | 0.78 ± 0.02a,b |

| Urinary ALB to creatinine ratio (mg/mmol) | 0.81 ± 0.18 | 3.07 ± 0.36a | 1.32 ± 0.21 | 5.03 ± 1.27a,b,c |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 24.3 ± 0.9 | 29.5 ± 1.7a | 26.3 ± 1.5 | 35.2 ± 3.1a,b,c |

P < 0.05 vs. Atg5lox/lox control.

P < 0.05 vs. respective non DM.

P < 0.05 vs. Atg5lox/lox control DM.

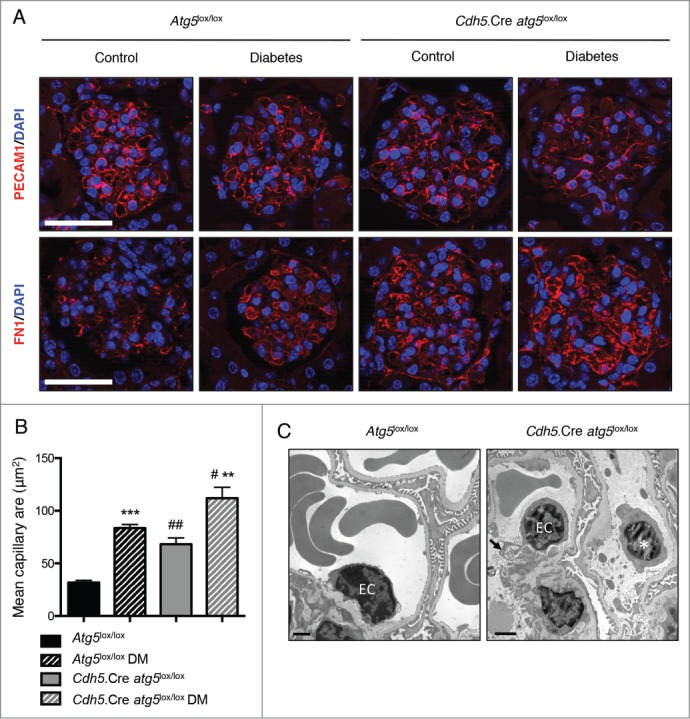

Figure 7.

Deletion of Atg5 specifically in endothelial cells favors the development of glomerular endothelial lesions during diabetes. (A) Representative images of the expression of PECAM1 (red, upper panel) and FN1 (red, lower panel) by immunofluorescence in 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Nuclei are counterstained with DAPI stain (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of the mean capillary area. Values are means ± SEM of 3 (nondiabetic) or 4 (diabetic) mice. # P <0.05, ** ## P<0.01, *** P<0.001, * same genotype, different treatment, # different genotype, same treatment. (C) Representative photomicrographs of transmission electron microscopy sections of glomeruli from 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control diabetic and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice showing cell detached in the lumen of the capillaries, most probably endothelial cells (*) and cytoplasmic vacuolization (arrows) in endothelial cells (EC) of Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Scale bar: 1 μm.

Endothelial-specific Atg5 deficiency results in diabetes-induced glomerular endothelial lesions

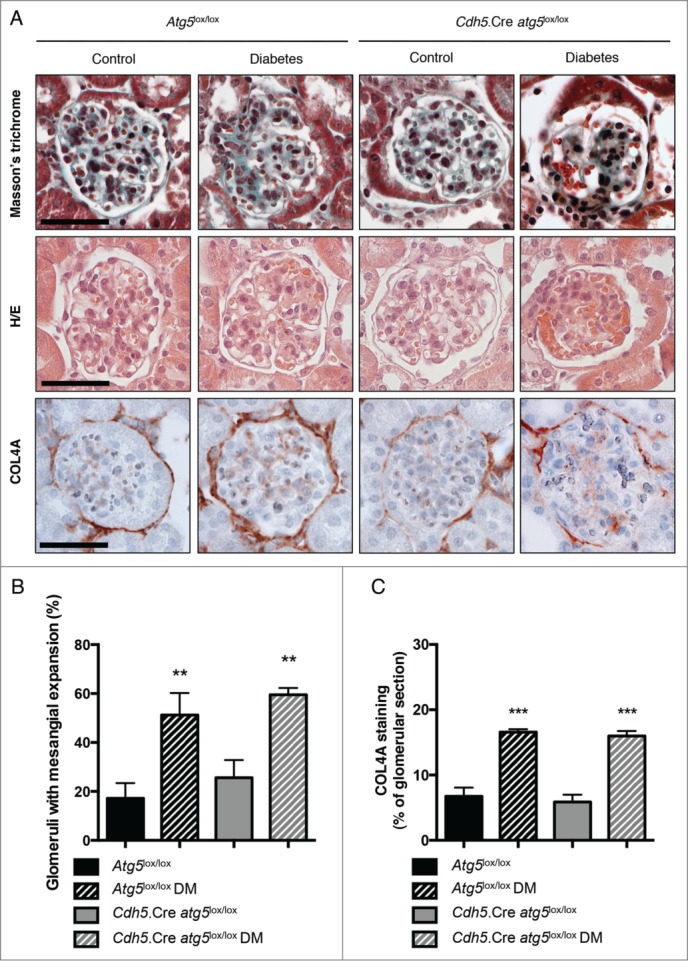

We then examined the role of the autophagy pathway in glomerular endothelial cells after the experimental induction of DM. Ten wk after the induction of diabetes by STZ injection, Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice and their control littermates presented polyuria, weight loss, and developed features of mild DN (Table 2 and data not shown). Importantly, microalbuminuria was more severe in Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice than in their control diabetic littermates (Table 2). Histological analyses showed that capillary mean area was increased in Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice when compared to their Atg5lox/lox control diabetic littermates (Figs. 7A, B and Fig. 8). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that PECAM1 staining was less intense and periluminal FN1/fibronectin staining was higher in glomeruli from Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice than in those of control diabetic mice. This indicates that glomerular capillaries are dilated and endothelial lesions are present in diabetic mice with endothelial cells deficient in autophagy (Fig. 7A). Ultrastructural analysis revealed glomerular endothelial cell cytoplasmic disorganization and vacuolization as well as detached cells, most probably endothelial cells, in the lumen of the capillaries, in glomeruli of Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice, further confirming endothelial injury in glomeruli from diabetic Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox mice (Fig. 7C and Fig. S6B). Histological analyses also revealed that mesangial thickening and glomerulosclerosis were similar between Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice and their control diabetic littermates (Fig. 8A, B). Likewise, COL4A deposition was similar in glomeruli from Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice and their control diabetic littermates (Fig. 8A, C).

Figure 8.

Deletion of Atg5 specifically in endothelial cells does not promote diabetes-induced glomerulosclerosis. (A) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin stained sections (upper panel), Masson trichrome stained sections (middle panel) and COL4A immunohistochemistry (lower panel) of renal cortex from 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Quantification of the percentage of glomeruli with mesangial expansion in renal cortex from 20-week-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Data represent means ± SEM of at least 5 mice. ** P < 0.01, * same genotype, different treatment. (C) Quantification of the COL4A staining per glomerular section in 20-wk-old Atg5lox/lox control, Atg5lox/lox control diabetic, Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox control and Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice. Data represent means ±SEM of 3 (nondiabetic) or 4 (diabetic) mice. *** P < 0.001, * same genotype, different treatment.

Finally, we investigated podocyte structure and number in diabetic mice. The intensity and pattern of PODXL and NPHS2 expression were different between glomeruli from Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic mice and those of their control littermates, whereas the podocyte density was similar (Fig. S7A, B). TEM observations revealed GBM thickening and podocyte foot process broadening and effacement in Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox diabetic glomeruli, whereas few ultrastructural defects were found in podocytes from control diabetic mice (Fig. S7C).

Overall, these results demonstrate that autophagy in endothelial cells exerts a protective effect on glomeruli during DM. Indeed, autophagy preserves both endothelial integrity and podocyte ultrastructure to maintain GFB homeostasis, which involves crosstalk between glomerular endothelial cells and surrounding podocytes.

Discussion

In this study, we highlight that autophagic flux underlies glomerular maintenance in response to DN in both cellular compartments of the GFB, podocytes and glomerular endothelial cells (GECs). Thus, our results indicate that autophagy protects glomeruli against injury in a diabetic context. These results shed light on the role of autophagy in DN and have important implications for limiting cell stress due to hyperglycemia.

Diabetes is the most common cause of ESRD in developed countries. Around 30% of patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes will develop proteinuria after 25 y of diabetes.58 Diabetic nephropathy is a slow progressive condition. Its clinical features are an increase in urinary albumin excretion in combination with rising blood pressure, both leading to a high risk of cardiovascular disease. A reduction in glomerular filtration rate occurs relatively late, around the same time as capillary rarefaction and sclerosis, and finally leads to ESRD. At the cellular level, both sides of the GFB, podocytes and GECs, are damaged in diabetic patients. Epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that intensive glycemic control significantly reduces the risk of developing microalbuminuria in type 1 and type 2 diabetes.59-61 The effect of glycemic control on the progression of microalbuminuria to ESRD is less clear.62-64 However, several studies have demonstrated that hyperglycemia has a deleterious effect on both podocytes and GECs.

In the present study, we investigated the importance of autophagy in podocytes and endothelial cells in the context of diabetes. Indeed, autophagy is likely to play an essential role in maintaining podocyte function, because these terminally differentiated cells display high rates of autophagy even in the absence of stress. 13,65-67

Because, endothelial dysfunction is associated with human diabetic nephropathy,68 we also sought to investigate, for the first time, the importance of endothelial autophagy in the maintenance of specialized glomerular microcirculation in normal and diabetic conditions.

Sustak et al. showed that high glucose levels lead to podocyte apoptosis in vitro, mediated through CASP3 activation.69 High glucose concentration (HG) also leads to podocyte hypertrophy through the upregulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1B/p27Kip1,70 and MTOR activation.50,71 Therefore, HG is expected to promote podocyte injury by perturbing cell cycle regulation, and promoting hypertrophy, dedifferentiation and apoptosis.

We first examined the effect of HG treatment in vitro and found that acute HG induces autophagy in primary cultured podocytes and stimulates apoptosis. These results are in line with those of a recent study showing that HG promotes the production of reactive oxygen species, which results in autophagy in a conditionally immortalized murine podocyte cell line.49 We then observed that long-term exposure to HG in vivo induces autophagy in podocytes. Furthermore, we found that autophagy deficiency in primary cultured podocytes under HG stimulation impaired cell survival. Similarly, indirect pharmacological autophagy inhibition in a conditionally immortalized murine podocyte cell line also induced apoptosis.72 Unlike this latter study, we used a genetic approach to study the effect of autophagy deficiency in primary podocytes in vitro and in vivo; therefore, our model is more physiologically relevant.

An important theme of this study was to target both cellular compartments of the GFB in the context of one disease. In fact, the results indicate that certain pathways act synergistically in both compartments, which identifies promising targets for novel treatment approaches.

In this respect, it is interesting that autophagy has protective properties in glomeruli during diabetes on both sides of the GFB. Furthermore, it appears interesting that the loss of autophagy in podocytes affects the ultrastructure and function of these cells but also that of nearby mesangial cells, which become sclerotic. These data underline the communication between podocytes and mesangial cells. In a similar manner, the loss of autophagy in endothelial cells alters the phenotype of GECs in addition to that of neighboring podocytes in diabetic conditions. Interestingly, crosstalk between endothelial cells and podocytes appears to involve a complex paracrine signaling network that is essential for glomerular development and homeostasis. This network is altered in disease and manifests as the abnormal excretion of albumin. However, it is unclear how autophagy may influence GEC-derived soluble factor(s) that signal to podocytes.

In the kidney, indirect evidence from experiments with well-known inducers of autophagy also suggest that autophagy has protective properties during the development of DN.24 Rapamycin, resveratrol, and caloric restriction induce autophagy in many cell types and organs. Although they affect many pathways besides autophagy, several studies have shown that these treatments have positive effects on inflammation, tubular injury, glomerulosclerosis, and podocyte injury in rodent models of DN.73-80 Interestingly, Wen et al. show that the treatment of diabetic mice with resveratrol impairs intraglomerular capillary rarefaction, suggesting that resveratrol attenuates diabetic nephropathy by modulating angiogenesis. We show that autophagy deficiency in endothelial cells leads to intraglomerular capillary rarefaction in diabetic animals, which suggests that resveratrol acts at least in part through this pathway. It is still unclear how autophagy in endothelial cells affects the permeability of the GFB to albumin in diabetic mice. There is a strong relationship between endothelial dysfunction and diabetic nephropathy in humans68,81 and vascular autophagy was recently shown to be important for NO production caused by the exposure of endothelial cells to shear stress in vitro.82 In addition, full NOS3 deficiency sensitizes mice to type I31 or type II DN.83,84 Furthermore, the −786C NOS3 gene variant is associated with a high urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio and a high risk of albuminuria in European American families.85 The low expression of NOS3 in mice, comparable to that associated with human NOS3 variants, promotes diabetic nephropathy independent of its effects on blood pressure.86 In summary, such a link between autophagy and endothelial function is consistent with our data. Little is known about the direct effects of HG on GECs and glomerular permselectivity. The permeability of GEC monolayers to bovine albumin is high after incubation with HG medium,87 and this may be linked to degradation of the glomerular endothelial glycocalyx.88,89 However, autophagy has not been reported to affect endothelial glycocalyx. Further studies will be needed to decipher the complex role of autophagy in endothelial function in vivo.

The new murine models of diabetic nephropathy that we developed in this study reveal the direct protective role of autophagy in glomeruli during the progression of DN and suggest that pharmacological induction of autophagy during diabetes has promising therapeutic potential to improve kidney function. This may also apply to other target organ damage and cardiovascular complications such as retinopathy, pancreas alteration, and diabetic heart disease in patients.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice with a podocyte-specific disruption of the Atg5 gene (Nphs2.Cre-atg5lox/lox) were generated by crossing Nphs2.Cre mice 56 with Atg5lox/lox mice.55 Mice with an endothelial-specific disruption of the Atg5 gene (Cdh5.Cre-atg5lox/lox) were generated by crossing Cdh5.Cre mice 57 with Atg5lox/lox mice.55 Mice were bred on pure C57BL/6J genetic background. Littermates Atg5lox/lox mice with no Cre gene were used as controls in all studies. GFP-LC3 mice were described previously.90

Characterization of Cdh5.Cre activity in glomerular endothelial cells in vivo was performed using 2 reporter mouse lines. The B6;129S4-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor/J strain91 in which Cre expression results in the removal of a loxP-flanked DNA segment that prevents expression of a lacZ gene. When crossed with a Cre transgenic strain, lacZ is expressed in cells/tissues where Cre is expressed. The B6.129X1-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(EYFP)Cos/J that have a loxP-flanked STOP sequence followed by the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein gene (EYFP) inserted into the Gt(ROSA)26Sor locus.92 When bred to mice expressing Cre recombinase, the STOP sequence is deleted and EYFP expression is observed in the Cre-expressing tissue(s) of the double-mutant offspring. These mutant mice were useful in monitoring the CDH5-cre expression in kidneys.

For the assessment of autophagic flux in glomeruli, mice were subjected to intraperitoneal injection with chloroquine diphosphate (50 mg/kg body weight; Sigma-Aldrich, C6628) every 24 h for 4 d.93 All mice were given free access to water and standard chow. Experiments were conducted according to French veterinary guidelines and those formulated by the European Commission for experimental animal use (L358–86/609EEC) and were approved by INSERM.

Induction of diabetes mellitus with streptozotocin (STZ)

Twelve-wk-old males were rendered diabetic by STZ (Sigma-Aldrich, S-0130) (100 mg/kg in sodium citrate buffer pH = 4.5) intraperitoneal injection on 2 consecutive d. Control mice received citrate buffer alone. Mice with fasting glycemia above 300 mg/dL were considered diabetic. Mice were killed 10 wk after the induction of diabetes.

Assessment of renal function and albuminuria

Urinary creatinine and BUN concentrations were quantified spectrophotometrically by colorimetric methods. Urinary albumin excretion was measured with a specific ELISA assay (Cusabio, CSB-E13878m).

Isolation of glomeruli and primary podocyte cultures

Decapsulated glomeruli were isolated as described previously.94,95 Briefly, freshly isolated renal cortex was mixed and digested by collagenase I (2 mg/mL; Gibco, 17100–017) in RPMI 1640 (Life Technologies, 61870–044). Tissues were then passed through 70 μm and 40 μm cell strainers (BD falcon, 352350 and 352340). Glomeruli, which adhere to the 40 μm cell strainer, were removed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Life Technologies, 10010023) + 0.5% BSA (Sigma Aldrich, A7906) injected under pressure, and were then washed twice in PBS. Freshly isolated glomeruli were plated in 6-well dishes in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, 15140–122) to allow podocytes to exit from glomeruli and grow. Each mouse was represented by one independent podocyte primary culture. Every experiment was reproduced at least 3 times using 3 different mice in order to obtain n = 3 independent primary podocyte cultures. Podocytes were detached and suspended in RIPA extraction buffer and frozen at −80°C for protein extraction or in RLT extraction buffer (Qiagen, 79216) and frozen at −80°C for total RNA extraction. In order to adjust various glucose concentrations, RPMI 1640 without glucose (Life Technologies 11879–020) was supplemented with D-glucose (Sigma Aldrich, G8644). Purity of culture of differentiated primary podocytes was verified as previously described.34

Histopathology and immunohistochemistry

Kidneys were immersed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4-μm thick) were stained with hematoxylin/eosin or Masson's trichrome and processed for histopathology or immunohistochemistry. For immunohistochemistry, paraffin-embedded sections were stained with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-WT1 (Abcam, ab89901, 1:100), goat anti-PODXL (R&D systems, BAF1556, 1:200), rabbit anti-FN1 (Millipore, AB2033, 1:100), rat anti-PECAM1 (Dianova, clone SZ31, 1:50), rabbit anti-COL4A (Abcam, ab19808, 1:100). WT1 and COL4A staining was revealed with Histofine® reagent (Nichirei Biosciences, 414141F). For NPHS2 immunofluorescence, fresh cryostat sections (4-μm thick) were immediately fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, 158127) then incubated with a goat anti-NPHS2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, G-20; 1:100). For GFP immunofluorescence, cells grown on Lab-Tek® chamber slides were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde then incubated with a rabbit anti-GFP antibody (Abcam, ab290; 1:1000). For immunofluorescence, the following secondary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-goat IgG AF594-conjugated antibody (A-11008), donkey anti-rabbit IgG AF488-conjugated antibody (A-21206), donkey anti-rat AF594-conjugated antibody (A-21209) (all from Invitrogen; 1:400). The nuclei were stained with DAPI. Photomicrographs were taken with an Axiophot Zeiss photomicroscope (Jena, Germany).

For LacZ staining, kidneys were fixed for 45 min at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. They were then extensively rinsed in PBS, and incubated at 4°C in PBS, 15% sucrose (Sigma Aldrich, S0389) for at least 24 h. Tissues were then embedded in PBS, 15% sucrose, 7.5% gelatin (Sigma Aldrich, 48723) and frozen at −80°C and stored at −20°C. Frozen sections (7 to 10 µm) were cut with a cryostat (Leica, CM1850) and stored at −20°C until use. After thawing and hydration in PBS, sections were stained at 37°C in X-gal coloration buffer: PBS containing 1 mg/ml X-gal (Euromedex, EU0012-D), 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide (Sigma Aldrich, P3289), 5 mM potassium ferricyanide (Sigma Aldrich, 702587), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.01% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich, X100). The color formation was stopped by washing in PBS, and slides were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Histopathology

ImageJ software (NIH) was used for assessment of capillary area, GBM thickness, foot process width and COL4A surface. Capillary area was measured randomly in 5 capillary loops per glomerulus in 5 different glomerular sections per animal for 4 different animals per condition. Capillary area was measured on immunofluorescence pictures for costaining of PODXL, PECAM1 and DAPI allowing to clearly identify capillary contours.

COL4A staining surface was quantified on 5 glomerular sections per mice in 3 nondiabetic and 4 diabetic mice and normalized to glomerular surface.

The proportion of pathologic glomeruli was evaluated by examination of at least 50 glomeruli per cortex section for each mouse, by an examiner (P.-L.T.) who was blinded to the experimental conditions. Mesangial expansion is defined as increase in extracellular material in the mesangium such that the width of the interspace exceeds 2 mesangial cell nuclei in at least 2 glomerular lobules.96

Electron microscopy

Small pieces of renal cortex were fixed in trump's fixative (EMS, 11750) and embedded in Araldite M (Sigma Aldrich, 10951). Ultrathin sections were counter-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a transmission electron microscope (JEM, JEOL 1011, Peabody, MA, USA).

Western blot analysis

Glomerular and podocyte lysates were prepared with RIPA extraction buffer. Equal amounts of proteins were loaded onto sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide electrophoresis gels for separation and transferred onto poly(vinylidenedifluoride) membranes. The membranes were blocked with milk and probed with different antibodies: rabbit anti-LC3B (Cell Signaling Technology, clone D11, 3868; 1:1000), rabbit anti-CASP3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9662; 1:1000), rabbit anti-cleaved CASP3 (Cell Signaling Technology, 9661; 1:1000), rabbit anti-ATG5 (Cell Signaling Technology, 2630; 1:1000), rabbit anti-ubiquitin (Cell Signaling Technology, 3936; 1:1000), guinea-pig anti-SQSTM1 (Progen, GP62-C, 1:10000), rabbit anti-NPHS2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 22298; 1:1000), rabbit anti-NPHS1 (Sigma Aldrich, PR52265; 1:1000), rabbit anti-GFP (Abcam ab290; 1:5000) and rat anti-TUBA/α-tubulin (Abcam, ab6160; 1:5000). The membranes were then probed with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, 7074 and 7076; 1:2000; Jackson Immunoresearch, 706-036-148; 1:1000) and the bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Clarity Western ECL substrate; Bio-Rad, 170–5061). An LAS-4000 imaging system (Fuji, LAS4000, Burlington, NJ, USA) was used to reveal bands and densitometric analysis was used for quantification.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were calculated with Graph Pad Prism (GraphPad software). Comparison between 2 groups was performed with a 2-tailed Student t test. Comparisons between multiple groups were performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank Professor Noboru Mizushima (Department of Physiology and Cell Biology, Tokyo Medical and Dental University) for the helpful development and sharing of the transgenic GFP-LC3 and Atg5 lox mouse strains. We thank the team at RIKEN BioResource Center for helping in obtaining these mice. We thank Elizabeth Huc, Emmanuel Salvado, Stacy Lecherbourg, and the ERI970 team for assistance in animal care and handling. We thank Véronique Oberweiss, Annette De Rueda, Martine Autran, Bruno Pillard, and Philippe Coudol for administrative support.

Funding

This study was supported by INSERM, Joint Transnational Call 2011 for “Integrated Research on Genomics and Pathophysiology of the Metabolic Syndrome and the Diseases arising from it” from l'Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) of France and the “VASCULOPHAGY” grant from the Fondation de France (P-LT). OL held a postdoctoral fellowship from Région Ile-de-France (CORDDIM) and the Société Francophone du Diabète (SFD). This study was also supported by the German Research Foundation DFG KFO 201 (to TBH), by the DFG (Heisenberg program and CRC 992 to TBH), by the European Research Council (ERC grant to TBH), and by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments (to TBH).

Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher's website.

References

- 1.Van Buren PN, Toto R. Current update in the management of diabetic nephropathy. Curr Diabetes Rev 2013; 9:62-77; PMID:23167665; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/157339913804143207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ziyadeh FN, Hoffman BB, Han DC, Iglesias-De La Cruz MC, Hong SW, Isono M, Chen S, McGowan TA, Sharma K. Long-term prevention of renal insufficiency, excess matrix gene expression, and glomerular mesangial matrix expansion by treatment with monoclonal antitransforming growth factor-beta antibody in db/db diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000; 97:8015-20; PMID:10859350; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.120055097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziyadeh FN, Mediators of diabetic renal disease: the case for tgf-Beta as the major mediator. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15 Suppl 1:S55-7; PMID:14684674; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/01.ASN.0000093460.24823.5B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Najafian B, Alpers CE, Fogo AB. Pathology of human diabetic nephropathy. Contrib Nephrol 2011; 170:36-47; PMID:21659756; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000324942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawagishi T, Matsuyoshi M, Emoto M, Taniwaki H, Kanda H, Okuno Y, Inaba M, Ishimura E, Nishizawa Y, Morii H. Impaired endothelium-dependent vascular responses of retinal and intrarenal arteries in patients with type 2 diabetes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999; 19:2509-16; PMID:10521381; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.ATV.19.10.2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishimura E, Nishizawa Y, Kawagishi T, Okuno Y, Kogawa K, Fukumoto S, Maekawa K, Hosoi M, Inaba M, Emoto M, et al.. Intrarenal hemodynamic abnormalities in diabetic nephropathy measured by duplex Doppler sonography. Kidney Int 1997; 51:1920-7; PMID:9186883; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ki.1997.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eleftheriadis T, Antoniadi G, Pissas G, Liakopoulos V, Stefanidis I. The renal endothelium in diabetic nephropathy. Ren Fail 2013; 35:592-9; PMID:23472883; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3109/0886022X.2013.773836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lindenmeyer MT, Kretzler M, Boucherot A, Berra S, Yasuda Y, Henger A, Eichinger F, Gaiser S, Schmid H, Rastaldi MP, et al.. Interstitial vascular rarefaction and reduced VEGF-A expression in human diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18:1765-76; PMID:17475821; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2006121304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stitt-Cavanagh E, MacLeod L, Kennedy C. The podocyte in diabetic kidney disease. ScientificWorldJournal 2009; 9:1127-39; PMID:19838599; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1100/tsw.2009.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziyadeh FN, Wolf G. Pathogenesis of the podocytopathy and proteinuria in diabetic glomerulopathy. Curr Diabetes Rev 2008; 4:39-45; PMID:18220694; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/157339908783502370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy GR, Kotlyarevska K, Ransom RF, Menon RK. The podocyte and diabetes mellitus: is the podocyte the key to the origins of diabetic nephropathy? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2008; 17:32-6; PMID:18090667; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282f2904d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huber TB, Edelstein CL, Hartleben B, Inoki K, Jiang M, Koya D, Kume S, Lieberthal W, Pallet N, Quiroga A, et al.. Emerging role of autophagy in kidney function, diseases and aging. Autophagy 2012; 8:1009-31; PMID:22692002; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.19821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartleben B, Godel M, Meyer-Schwesinger C, Liu S, Ulrich T, Kobler S, Wiech T, Grahammer F, Arnold SJ, Lindenmeyer MT, et al.. Autophagy influences glomerular disease susceptibility and maintains podocyte homeostasis in aging mice. J Clin Invest 2010; 120:1084-96; PMID:20200449; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI39492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boya P, Reggiori F, Codogno P. Emerging regulation and functions of autophagy. Nat Cell Biol 2013; 15:713-20; PMID:23817233; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B. Autophagy in human health and disease. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1845-6; PMID:23656658; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMra1205406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF. Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol 2010; 221:3-12; PMID:20225336; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/path.2697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shibata M, Lu T, Furuya T, Degterev A, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, MacDonald M, Yankner B, Yuan J. Regulation of intracellular accumulation of mutant Huntingtin by Beclin 1. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:14474-85; PMID:16522639; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M600364200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12:814-22; PMID:20811353; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb0910-814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh R, Xiang Y, Wang Y, Baikati K, Cuervo AM, Luu YK, Tang Y, Pessin JE, Schwartz GJ, Czaja MJ. Autophagy regulates adipose mass and differentiation in mice. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:3329-39; PMID:19855132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubinsztein DC, Marino G, Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell 2011; 146:682-95; PMID:21884931; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melendez A, Talloczy Z, Seaman M, Eskelinen EL, Hall DH, Levine B. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science 2003; 301:1387-91; PMID:12958363; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1087782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipinski MM, Zheng B, Lu T, Yan Z, Py BF, Ng A, Xavier RJ, Li C, Yankner BA, Scherzer CR, et al.. Genome-wide analysis reveals mechanisms modulating autophagy in normal brain aging and in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107:14164-9; PMID:20660724; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1009485107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia G, Cheng G, Agrawal DK. Autophagy of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerotic lesions. Autophagy 2007; 3:63-4; PMID:17172800; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.3427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kume S, Thomas MC, Koya D. Nutrient sensing, autophagy, and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 2012; 61:23-9; PMID:22187371; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/db11-0555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kume S, Uzu T, Maegawa H, Koya D. Autophagy: a novel therapeutic target for kidney diseases. Clin Exp Nephrol 2012; 16:827-32; PMID:22971965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10157-012-0695-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weide T, Huber TB. Implications of autophagy for glomerular aging and disease. Cell Tissue Res 2011; 343:467-73; PMID:21286756; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00441-010-1115-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deckert T, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen T, Kofoed-Enevoldsen A. Albuminuria reflects widespread vascular damage. The Steno hypothesis. Diabetologia 1989; 32:219-26; PMID:2668076; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00285287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rask-Madsen C, King GL. Vascular complications of diabetes: mechanisms of injury and protective factors. Cell Metab 2013; 17:20-33; PMID:23312281; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Advani A, Gilbert RE. The endothelium in diabetic nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 2012; 32:199-207; PMID:22617769; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goligorsky MS, Chen J, Brodsky S. Workshop: endothelial cell dysfunction leading to diabetic nephropathy : focus on nitric oxide. Hypertension 2001; 37:744-8; PMID:11230367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.HYP.37.2.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakagawa T, Sato W, Glushakova O, Heinig M, Clarke T, Campbell-Thompson M, Yuzawa Y, Atkinson MA, Johnson RJ, Croker B. Diabetic endothelial nitric oxide synthase knockout mice develop advanced diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18:539-50; PMID:17202420; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2006050459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieuwdorp M, Mooij HL, Kroon J, Atasever B, Spaan JA, Ince C, Holleman F, Diamant M, Heine RJ, Hoekstra JB, et al.. Endothelial glycocalyx damage coincides with microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2006; 55:1127-32; PMID:16567538; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oltean S, Qiu Y, Ferguson JK, Stevens M, Neal C, Russell A, Kaura A, Arkill KP, Harris K, Symonds C, et al.. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor-A165b Is Protective and Restores Endothelial Glycocalyx in Diabetic Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; PMID:25542969; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2014040350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenoir O, Milon M, Virsolvy A, Henique C, Schmitt A, Masse JM, Kotelevtsev Y, Yanagisawa M, Webb DJ, Richard S, et al.. Direct action of endothelin-1 on podocytes promotes diabetic glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 25:1050-62; PMID:24722437; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2013020195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarafidis PA, Lasaridis AN. Diabetic nephropathy: Endothelin antagonism for diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol 2010; 6:447-9; PMID:20664627; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrneph.2010.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding SS, Qiu C, Hess P, Xi JF, Zheng N, Clozel M. Chronic endothelin receptor blockade prevents both early hyperfiltration and late overt diabetic nephropathy in the rat. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2003; 42:48-54; PMID:12827026; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00005344-200307000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruno CM, Meli S, Marcinno M, Ierna D, Sciacca C, Neri S. Plasma endothelin-1 levels and albumin excretion rate in normotensive, microalbuminuric type 2 diabetic patients. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2002; 16:114-7; PMID:12144123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fukui M, Nakamura T, Ebihara I, Osada S, Tomino Y, Masaki T, Goto K, Furuichi Y, Koide H. Gene expression for endothelins and their receptors in glomeruli of diabetic rats. J Lab Clin Med 1993; 122:149-56; PMID:8340699 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hohenstein B, Hausknecht B, Boehmer K, Riess R, Brekken RA, Hugo CP. Local VEGF activity but not VEGF expression is tightly regulated during diabetic nephropathy in man. Kidney Int 2006; 69:1654-61; PMID:16541023; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.ki.5000294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu E, Morimoto M, Kitajima S, Koike T, Yu Y, Shiiki H, Nagata M, Watanabe T, Fan J. Increased Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Kidney Leads to Progressive Impairment of Glomerular Functions. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007; 18:2094-104; PMID:17554151; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2006010075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeansson M, Gawlik A, Anderson G, Li C, Kerjaschki D, Henkelman M, Quaggin SE. Angiopoietin-1 is essential in mouse vasculature during development and in response to injury. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:2278-89; PMID:21606590; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI46322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosokawa N, Hara T, Kaizuka T, Kishi C, Takamura A, Miura Y, Iemura S, Natsume T, Takehana K, Yamada N, et al.. Nutrient-dependent mTORC1 association with the ULK1-Atg13-FIP200 complex required for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 2009; 20:1981-91; PMID:19211835; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoyer-Hansen M, Jaattela M. AMP-activated protein kinase: a universal regulator of autophagy? Autophagy 2007; 3:381-3; PMID:17457036; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.4240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mack HI, Zheng B, Asara JM, Thomas SM. AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of ULK1 regulates ATG9 localization. Autophagy 2012; 8:1197-214; PMID:22932492; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.20586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee IH, Cao L, Mostoslavsky R, Lombard DB, Liu J, Bruns NE, Tsokos M, Alt FW, Finkel T. A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:3374-9; PMID:18296641; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0712145105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13:132-41; PMID:21258367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncb2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park EY, Park JB. High glucose-induced oxidative stress promotes autophagy through mitochondrial damage in rat notochordal cells. Int Orthop 2013; 37:2507-14; PMID:23907350; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00264-013-2037-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen H, Luo Z, Sun W, Zhang C, Sun H, Zhao N, Ding J, Wu M, Li Z, Wang H. Low glucose promotes CD133mAb-elicited cell death via inhibition of autophagy in hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 2013; 336:204-12; PMID:23652197; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma T, Zhu J, Chen X, Zha D, Singhal PC, Ding G. High glucose induces autophagy in podocytes. Exp Cell Res 2013; 319:779-89; PMID:23384600; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Godel M, Hartleben B, Herbach N, Liu S, Zschiedrich S, Lu S, Debreczeni-Mór A, Lindenmeyer MT, Rastaldi MP, Hartleben G, et al.. Role of mTOR in podocyte function and diabetic nephropathy in humans and mice. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:2197-209; PMID:21606591; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI44774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu L, Feng Z, Cui S, Hou K, Tang L, Zhou J, Cai G, Xie Y, Hong Q, Fu B, et al.. Rapamycin upregulates autophagy by inhibiting the mTOR-ULK1 pathway, resulting in reduced podocyte injury. PLoS One 2013; 8:e63799; PMID:23667674; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0063799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanida I, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and Autophagy. Methods Mol Biol 2008; 445:77-88; PMID:18425443; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-59745-157-4_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al.. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 2012; 8:445-544; PMID:22966490; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.19496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 2010; 140:313-26; PMID:20144757; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakahara Y, Suzuki-Migishima R, Yokoyama M, Mishima K, Saito I, Okano H, et al.. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 2006; 441:885-9; PMID:16625204; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature04724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moeller MJ, Sanden SK, Soofi A, Wiggins RC, Holzman LB. Podocyte-specific expression of cre recombinase in transgenic mice. Genesis 2003; 35:39-42; PMID:12481297; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/gene.10164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oberlin E, El Hafny B, Petit-Cocault L, Souyri M. Definitive human and mouse hematopoiesis originates from the embryonic endothelium: a new class of HSCs based on VE-cadherin expression. Int J Dev Biol 2010; 54:1165-73; PMID:20711993; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1387/ijdb.103121eo [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ritz E, Zeng XX, Rychlik I. Clinical manifestation and natural history of diabetic nephropathy. Contrib Nephrol 2011; 170:19-27; PMID:21659754; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000324939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pirart J. ; Diabetes mellitus and its degenerative complications: a prospective study of 4,400 patients observed between 1947 and 1973 (author's transl). Diabete Metab 1977; 3:97-107; PMID:892130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kilpatrick ES, Rigby AS, Atkin SL. A1C variability and the risk of microvascular complications in type 1 diabetes: data from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care 2008; 31:2198-202; PMID:18650371; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/dc08-0864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fioretto P, Bruseghin M, Berto I, Gallina P, Manzato E, Mussap M. Renal protection in diabetes: role of glycemic control. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:S86-9; PMID:16565255; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2005121343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bojestig M, Arnqvist HJ, Karlberg BE, Ludvigsson J. Glycemic control and prognosis in type I diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. Diabetes Care 1996; 19:313-7; PMID:8729152; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/diacare.19.4.313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Feldt-Rasmussen B, Mathiesen ER, Deckert T. Effect of two years of strict metabolic control on progression of incipient nephropathy in insulin-dependent diabetes. Lancet 1986; 2:1300-4; PMID:2878175; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91433-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Feldt-Rasmussen B. The development of nephropathy in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is associated with poor glycemic control. Transplant Proc 1994; 26:371-2; PMID:8171466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Asanuma K, Tanida I, Shirato I, Ueno T, Takahara H, Nishitani T, Kominami E, Tomino Y. MAP-LC3, a promising autophagosomal marker, is processed during the differentiation and recovery of podocytes from PAN nephrosis. FASEB J 2003; 17:1165-7; PMID:12709412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sato S, Adachi A, Sasaki Y, Dai W. Autophagy by podocytes in renal biopsy specimens. J Nihon Med Sch 2006; 73:52-3; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1272/jnms.73.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sato S, Kitamura H, Adachi A, Sasaki Y, Ghazizadeh M. Two types of autophagy in the podocytes in renal biopsy specimens: ultrastructural study. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol 2006; 38:167-74; PMID:17784646 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakagawa T, Tanabe K, Croker BP, Johnson RJ, Grant MB, Kosugi T, Li Q. Endothelial dysfunction as a potential contributor in diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol 2011; 7:36-44; PMID:21045790; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrneph.2010.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Susztak K, Raff AC, Schiffer M, Bottinger EP. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 2006; 55:225-33; PMID:16380497; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2337/diabetes.55.01.06.db05-0894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wolf G, Schanze A, Stahl RA, Shankland SJ, Amann K. p27(Kip1) Knockout mice are protected from diabetic nephropathy: evidence for p27(Kip1) haplotype insufficiency. Kidney Int 2005; 68:1583-9; PMID:16164635; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00570.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Inoki K, Mori H, Wang J, Suzuki T, Hong S, Yoshida S, Blattner SM, Ikenoue T, Rüegg MA, Hall MN, et al.. mTORC1 activation in podocytes is a critical step in the development of diabetic nephropathy in mice. J Clin Invest 2011; 121:2181-96; PMID:21606597; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI44771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fang L, Li X, Luo Y, He W, Dai C, Yang J. Autophagy inhibition induces podocyte apoptosis by activating the pro-apoptotic pathway of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Exp Cell Res 2014; 322:290-301; PMID:24424244; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kitada M, Takeda A, Nagai T, Ito H, Kanasaki K, Koya D. Dietary restriction ameliorates diabetic nephropathy through anti-inflammatory effects and regulation of the autophagy via restoration of Sirt1 in diabetic Wistar fatty (fa/fa) rats: a model of type 2 diabetes. Exp Diabetes Res 2011; 2011:908185; PMID:21949662; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2011/908185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mori H, Inoki K, Masutani K, Wakabayashi Y, Komai K, Nakagawa R, Guan KL, Yoshimura A. The mTOR pathway is highly activated in diabetic nephropathy and rapamycin has a strong therapeutic potential. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009; 384:471-5; PMID:19422788; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sakaguchi M, Isono M, Isshiki K, Sugimoto T, Koya D, Kashiwagi A. Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin attenuates renal hypertrophy in the early diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 340:296-301; PMID:16364254; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang Y, Wang J, Qin L, Shou Z, Zhao J, Wang H, Chen Y, Chen J. Rapamycin prevents early steps of the development of diabetic nephropathy in rats. Am J Nephrol 2007; 27:495-502; PMID:17671379; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000106782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wen X, Wu J, Wang F, Liu B, Huang C, Wei Y. Deconvoluting the role of reactive oxygen species and autophagy in human diseases. Free Radic Biol Med 2013; 65:402-10; PMID:23872397; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xu F, Wang Y, Cui W, Yuan H, Sun J, Wu M, Guo Q, Kong L, Wu H, Miao L, et al.. Resveratrol Prevention of Diabetic Nephropathy Is Associated with the Suppression of Renal Inflammation and Mesangial Cell Proliferation: Possible Roles of Akt/NF-kappaB Pathway. Int J Endocrinol 2014; 2014:289327; PMID:24672545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Palsamy P, Subramanian S. Resveratrol protects diabetic kidney by attenuating hyperglycemia-mediated oxidative stress and renal inflammatory cytokines via Nrf2-Keap1 signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1812:719-31; PMID:21439372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chang CC, Chang CY, Wu YT, Huang JP, Yen TH, Hung LM. Resveratrol retards progression of diabetic nephropathy through modulations of oxidative stress, proinflammatory cytokines, and AMP-activated protein kinase. J Biomed Sci 2011; 18:47; PMID:21699681; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1423-0127-18-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jawa A, Nachimuthu S, Pendergrass M, Asnani S, Fonseca V. Impaired vascular reactivity in African-American patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria or proteinuria despite angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:31-5; PMID:16219712; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/jc.2005-1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bharath LP, Mueller R, Li Y, Ruan T, Kunz D, Goodrich R, Mills T, Deeter L, Sargsyan A, Anandh Babu PV, et al.. Impairment of autophagy in endothelial cells prevents shear-stress-induced increases in nitric oxide bioavailability. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2014; 92:605-12; PMID:24941409; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1139/cjpp-2014-0017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kamijo H, Higuchi M, Hora K. Chronic inhibition of nitric oxide production aggravates diabetic nephropathy in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats. Nephron Physiol 2006; 104:p12-22; PMID:16691035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000093276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhao HJ, Wang S, Cheng H, Zhang MZ, Takahashi T, Fogo AB, Breyer MD, Harris RC. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency produces accelerated nephropathy in diabetic mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 17:2664-9; PMID:16971655; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2006070798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu Y, Burdon KP, Langefeld CD, Beck SR, Wagenknecht LE, Rich SS, Bowden DW, Freedman BI. T-786C polymorphism of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with albuminuria in the diabetes heart study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16:1085-90; PMID:15743995; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2004100817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang CH, Li F, Hiller S, Kim HS, Maeda N, Smithies O, Takahashi N. A modest decrease in endothelial NOS in mice comparable to that associated with human NOS3 variants exacerbates diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:2070-5; PMID:21245338; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1018766108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nitta K, Horiba N, Uchida K, Horita S, Hayashi T, Kawashima A, Yumura W, Nihei H. High glucose modulates albumin permeability across glomerular endothelial cells via a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai Shi 1995; 37:317-22; PMID:7666597 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Singh H, Brindle NP, Zammit VA. High glucose and elevated fatty acids suppress signaling by the endothelium protective ligand angiopoietin-1. Microvasc Res 2010; 79:121-7; PMID:20079751; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Singh SK, Jeansson M, Quaggin SE. New insights into the pathogenesis of cellular crescents. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2011; 20:258-62; PMID:21455064; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32834583ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol Biol Cell 2004; 15:1101-11; PMID:14699058; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 1999; 21:70-1; PMID:9916792; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/5007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol 2001; 1:4; PMID:11299042; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bhuiyan MS, Pattison JS, Osinska H, James J, Gulick J, McLendon PM, Hill JA, Sadoshima J, Robbins J. Enhanced autophagy ameliorates cardiac proteinopathy. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:5284-97; PMID:24177425; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI70877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schiwek D, Endlich N, Holzman L, Holthofer H, Kriz W, Endlich K. Stable expression of nephrin and localization to cell-cell contacts in novel murine podocyte cell lines. Kidney Int 2004; 66:91-101; PMID:15200416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00711.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bollee G, Flamant M, Schordan S, Fligny C, Rumpel E, Milon M, Schordan E, Sabaa N, Vandermeersch S, Galaup A, et al.. Epidermal growth factor receptor promotes glomerular injury and renal failure in rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nat Med 2011; 17:1242-50; PMID:21946538; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tervaert TW, Mooyaart AL, Amann K, Cohen AH, Cook HT, Drachenberg CB, Ferrario F, Fogo AB. Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 21:556-63; PMID:20167701; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2010010010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.