Abstract

An aerosol formulation containing 7.5 mg of R-salbutamol sulfate was developed. The aerosol was nebulized with an air-jet nebulizer, and further assessed according to the new European Medicines Agency (EMA) guidelines. A breath simulator was used for studies of delivery rate and total amount of the active ingredient at volume of 3 mL. A next generation impactor (NGI) with a cooler was used for analysis of the particle size and in vitro lung deposition rate of the active ingredient at 5 °C. The anti-asthmatic efficacy of the aerosol formulation was assessed in guinea pigs with asthma evoked by intravenous injection of histamine compared with racemic salbutamol. Our results show that this aerosol formulation of R-salbutamol sulfate met all the requirements of the new EMA guidelines for nebulizer. The efficacy of a half-dose of R-salbutamol equaled that of a normal dose of racemic salbutamol.

KEY WORDS: R-salbutamol, Nebulizer, NGI, Particle size, Dose uniformity, Guinea pigs, Asthma

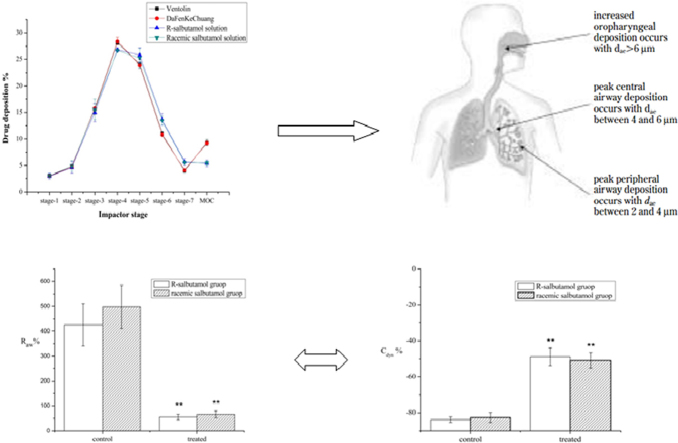

Graphical abstract

Drug particles will deposit in different stages of NGI which simulate the lower respiratory tract structure approximately. Also alleviation of airway hyperreactivity by inhaling R-salbutamol sulfate solution was validated both in airway resistance and in dynamic compliance of lung compared with racemic salbutamol.

1. Introduction

Acute severe asthma remains a serious and debilitating disease affecting billions of people, and the prevalence of asthma is increasing1,2. In China there are about 30 million asthmatics and 1/3 of the asthma patients are children. China is among the countries with the highest asthma mortality in the world3.

Use of bronchodilators, such as short acting β2-adrenoceptor agonists (SABA), is recommended as the first line treatment for an asthma attack by the guidelines of GINA (Global Initiative for Asthma) launched by the World Health Organization in 19954, and is also recommended by Medical Association of China5. Salbutamol sulfate, a SABA bronchodilator, has been one of the most common prescription drugs in China as well as in the world for several decades6,7.

Salbutamol is a chiral drug consisting of an R-enantiomer (the eutomer) and an S-enantiomer (the distomer). Studies have shown that the S-enantiomer of salbutamol is not only ineffective in treating asthma, but also toxic. The S-enantiomer can increase airway hyperreactivity and augment airways smooth muscle contractility in response to allergens8–10. These adverse effects are likely due to its pro-inflammatory effects 11,12 and to increases in the amount of histamine released from mast cells13,14. Pharmacokinetic experiments have shown that the bioavailability of the S-enantiomer is significantly higher than that of R-enantiomer after inhalation. The half-life of S-salbutamol, as indicated by elimination constants, was significantly longer than that of R-salbutamol after the racemate was inhaled, and this phenomenon was also found in oral administration, which was due to the enantioselectivity of sulphotransferase15. Repeated administrations of racemic salbutamol will result in successive increases in the S/R ratio as steady state is approached16. For patients with severe asthma, the long-term effects of inhaling racemic salbutamol can cause adverse effects, including nervousness, tremor and chest pain17. In controlled trials R-salbutamol caused a slightly lower incidence of nervousness than racemic salbutamol and smaller increases in heart rate18. S-isoprenaline and S-terbutaline, which are also used for the treatment of asthma, were also shown to evoke airway hyperresponsiveness8.

Due to the different pharmacological effects of enantiomers, the US FDA issued a long awaited policy statement concerning the development of stereoisomeric drugs in 1992. These drugs are also known as chiral drugs19. Switching from racemic drugs to single enantiomer drugs has been a trend in pharmaceutical innovation in recent years20. The FDA approved R-salbutamol hydrochloride inhalation solution in 1999 and R-salbutamol tartrate MDI in 2005 for asthma. However, none of these R-enantiomer formulations was approved for marketing in China. Until recently, salbutamol has been marketed as a racemic mixture rather than a pure enantiomer formulation in China. It is of great significance to develop R-salbutamol for the unmet medical need in China.

Inhalation therapy is widely employed to deliver drugs to treat respiratory diseases 21 and is accepted as the first-line therapy for the treatment of pediatric asthma22. A nebulizer provides a convenient way for the pulmonary delivery of drugs, especially for the elderly and children. Nebulizers of racemic salbutamol are widely prescribed for asthma in China. In 2007, the EMA introduced regulatory guidance on nebulizers23. The guidelines require determination of the deposition rate and the use of a breath simulator for determination of the active substance delivery rate and total amount of active substance delivered. The two-glass impactor has been used to evaluate the particle size distribution for inhalers for the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2010 edition), which can determine the dose of fine particle drug with aerodynamic diameter size less than 6.4 μm but cannot yield aerodynamic distribution24. The Chinese Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) likely will soon introduce similar guidelines to improve the standards of inhalers. This has imposed great challenges for developing new nebulizers that will meet these new standards. It is also important to validate the efficacy of R-salbutamol in comparison with racemic salbutamol, particularly given that there are some debates on the advantages of R-salbutamol25.

In this study, we have developed an aerosol formulation of the optically pure enantiomer of R-salbutamol sulfate. This aerosol formulation was assessed according to the new EMA and EPAG (European Pharmaceutical Aerosol Group) guidelines for nebulizer delivery of drugs. A breath simulator and next generation impactor were used for studies on the delivery rate and total amount of the active ingredient, as well as the particle or droplet size distribution. The anti-asthmatic efficacy of the aerosol formulation was also assessed in vivo compared to racemic salbutamol sulfate formulations currently available in China.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Hartley guinea pigs of either sex weighing 200±50 g were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Guangdong and housed in acrylic cages with food and water ad libitum under a 12-h light/dark cycle. All animals used for the studies were tested by inhaling histamine 24 h before the experiment. Animals which had a low response to histamine challenge were not used for this study. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Animal Welfare in the School of Bioscience and Bioengineering, South China University of Technology (Guangzhou, China).

2.2. Reagents

Ventolin and DaFenKeChuang inhalation solutions were purchased from a registered pharmacy in Guangzhou. Racemic salbutamol sulfate was purchased from Yabang Pharmaceutical limited company and the quality met the requirements of Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2010 edition). R-Salbutamol sulfate was provided by Key-Pharma Biomedical Inc., Dongguan, China. The salbutamol sulfate used as reference was purchased from National Institutes for Food and Drug Control of China. Histamine was obtained from Sigma. Sodium dihydrogen phosphate, ethylcarbamate and methanol were bought from commercial sources.

2.3. Instruments

Shimadzu high performance liquid chromatography (LC-20A) was used for the quantitative analysis of salbutamol. The nebulizer (Pari Turbo boy) used in this research was obtained from PARI Respiratory Equipment Inc. The particle size distribution was determined with the next generation impactor, which was manufactured by MSP Company in USA. A breath simulator model (BRS 2000, Copley scientific company) was used to determine dose delivery rate and total active substance delivered. Physiological parameters determined for the in vivo experiments included tidal volume, intrathoracic pressure, and flow rate; respiratory frequency and heart rate were recorded with a Power Lab Data Acquisition System by AD instruments Inc.

2.4. Chromatographic conditions

The chromatographic column used for analysis was an Agilent ODS column (150 mm×4.6 mm, 5 μm). Mobile phase was composed of 0.08 mol/L sodium dihydrogen phosphate solution (adjusted pH value to 3.10±0.05 with phosphoric acid) – methanol (85:15, v/v). The temperature during analysis was kept at 40 °C, and the detection wavelength was set at 276 nm.

2.5. Standard solution

The reference salbutamol sulfate bulk material was used for standard solutions. The solvent is composed of 15% methanol and 85% water (v/v).

2.6. Particle size distribution

NGI was operated at 15 L/min using a high capacity pump after cooling for 90 min at 5 °C according to the specifications of Chapter 2.9.44 in the EP (European Pharmacopoeia). All tests used an LC Plus nebulizer which was filled with 3 mL inhalation solution and operated as specified in the instruction manual to deliver aerosol for 10 min into the impactor circuit. The pump was kept running for an additional 10 s after each 10 min test in order to wash out the remaining liquid in the nozzle. The impactor was then dismantled and the samples were washed with ultra-pure water. The water was then removed to a volumetric flask. The flask was filled with methanol proportionally and the final ratio of water and methanol was 85:15.

2.7. Dose uniformity

For the dose-uniformity study, the operation was performed using the BRS 2000 according to the specifications of Chapter 2.9.44 in the EP. A standard sinusoidal adult pattern (500 mL tidal volume, 15 breaths/min, inhalation/exhalation ratio=1) was selected for the testing along with an LC Plus nebulizer filled with 3 mL of inhalation solution. The test time for delivery rate determination was 60 s but the total active substance was determined for 10 min, which was to make sure the 3 mL solution was atomized completely. It was necessary to change to a fresh filter during this process to prevent filter saturation. The filter and holder were washed after each test with ultra-pure water to remove the active ingredient. Methanol was then added to bring the final ratio of water to methanol to 85:15.

2.8. In vivo study

Guinea pigs (n=16) were anaesthetized with urethane (1.25 g/kg, intraperitoneal injection) and then intubated with a tracheal cannula. The jugular vein was cannulated to administer histamine. The animal was placed within a body plethysmograph (a 45 cm×11 cm×15 cm plastic box) in supine position. A 10-min stabilization was allowed in order to record baseline values including tidal volume, flow rate and intrathoracic pressure. An asthmatic response was evoked with histamine (15 μg/mL, 0.5 mL, intravenous injection) at 1 mL/min by syringe pump after inhalation of saline (3 mL in cup for 30 s). The changes in Raw (airway resistance) and Cdyn (dynamic compliance of lung) after the histamine challenge were expressed as percent of the baseline in either the R-salbutamol or racemic salbutamol group. The same animal was then allowed an additional 10 min for stabilization, after which a second histamine challenge was given (15 μg/mL 0.5 mL, intravenous injection) after the inhalation of either the aerosol of R-salbutamol (0.2 mg/mL, 30 s ) or racemic salbutamol (0.4 mg/mL, 30 s). The peak changes in Raw and Cdyn after histamine challenges were compared with the baseline values before the histamine challenge, and expressed as percent of the baseline (%). The percent changed from baseline (%) in Raw and Cdyn after being treated with saline (control), R-salbutamol or racemic salbutamol was then compared to determine the anti-asthmatic effects.

2.9. Analytical methods and statistics

2.9.1. Size distribution and dose uniformity

All the samples from NGI and BRS2000 were analyzed quantitatively by HPLC according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where m is the content of salbutamol for unknown samples (μg); A is the peak area of unknown samples; and V is the volume of unknown samples (mL). Copley Inhaler Testing Data Analysis (CITDA, UK) software was used for analyzing the size distribution.

2.9.2. Pulmonary function

Pulmonary function was characterized with two indexes: Raw and Cdyn, which were calculated from the parameters recorded using the following equations26,27:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where ΔPR is the intrathoracic pressure (cmH2O); ΔV is the flow rate (derivation of tidal volume, cmH2O/s); and VT is the tidal volume (cmH2O).

The percent changed from baseline (%) in Raw and Cdyn after treatment with saline (control), R-salbutamol or R,S-salbutamol was calculated using the following equations:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where R1 is the maximum value of Raw after challenge; R0 is the mean of Raw before challenge; C1 is the minimum value of Cdyn after challenge; and C0 is the mean of Cdyn before challenge.

Comparisons were made between groups using t-test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The aerosol formulation

Salbutamol sulfate has proved to have better chemical and physical stability than salbutamol while in racemic form28. Research on the decomposition of salbutamol sulfate in aqueous solution indicates that the maximum stability of salbutamol in aqueous solution occurred at an acidic pH29,30. Pharmaceutical requirements for an inhalation solution need to be considered carefully. Benzalkonium chloride, for example, has been classified to class I acute inhalation toxicity, and showed strong inflammatory and irritant activity on the lungs 6 h after inhalation, including increased patterns of IL-6 and IgE production31. Drug descriptions for levalbuterol HCl inhalation solution also conformed to the above requirements. Commercial products of racemic salbutamol at home and abroad were in the sulfate form. A hygroscopicity test was carried out using the two preparations of R-salbutamol API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) under 25±1 °C and 80±2% (relative humidity) conditions. The hygroscopicity of R-salbutamol sulfate was less than that of R-salbutamol hydrochloride, which was preferred in further formulations. According to prescription optimization, mainly on the control of pH, the final composition for R-salbutamol consisted of R-salbutamol 7.5 mg (or racemic salbutamol 7.5 mg) and saline 0.9%, with diluted H2SO4 to adjust the pH to 3.5. The final aerosol concentration for R-salbutamol or racemic salbutamol was 2.5 mg/mL. Both preparations were sterile, clear, colorless, and preservative-free solutions.

3.2. Evaluation of the analytical methods

Standard solutions with various concentrations of salbutamol were prepared and analyzed by HPLC. The area of UV absorption at each concentration was calculated. The correlation between the concentration and area of absorption was determined using linear regression. The lineal equation was y=9803.3x−3.2442 and the correlation coefficient was R2=1, where y is the concentration of R-salbutamol sulfate in solution (μg/mL) and x is the peak area of absorbance. The result indicates a high correlation between the concentration of salbutamol and area of absorbance as measured by HPLC.

3.3. Particle size distribution

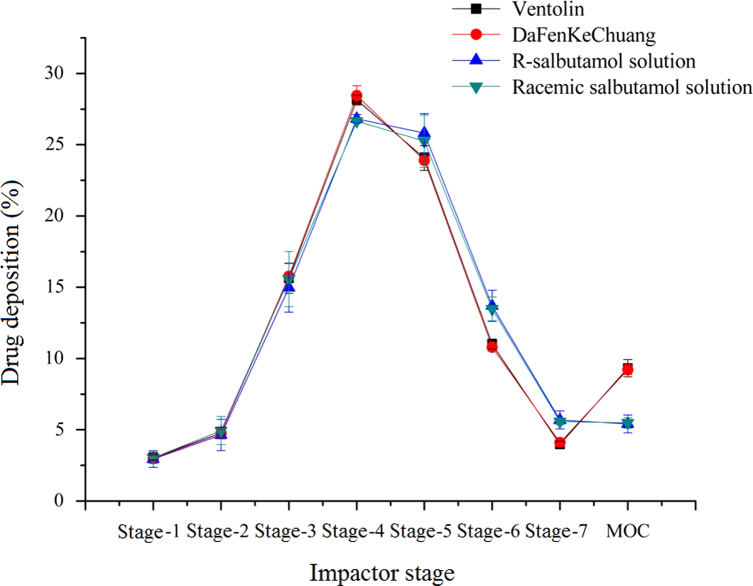

Generally, drug particles from a nebulizer will deposit in different parts in lungs according to their size: those drug particles will gradually deposit in primary bronchi, bronchi, terminal bronchi and alveoli in accordance with the particle size from large to small32,33. It is more valuable to determine the detailed deposition rate for inhalers with a cascade impactor, such as Anderson cascade impactor and Multistage liquid impinger and NGI. The aerosol particle size distribution (APSD) profiles of four aerosol solutions from stage-1 to MOC (micro-orifice collector) are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Drug deposition rate for four aerosol solutions in different stages. Data are expressed as mean±SD, n=3.

For particle size distribution, two major indexes can be generated with CITDA software according to the curve of drug deposition in different stages: FPF% (fine particle fraction, <5 μm) and MMAD (mass median aerodynamic diameter). FPF% represented the particle amount in which the diameter was less than or equal to 5 μm. Particles with this size were considered to be respirable34,35. MMAD is the diameter around which the mass of aerosol is equally divided. Both of these indices were used to evaluate the lung deposition rate in vitro in this study. These two indices were used to evaluate R-salbutamol aerosol, compared to racemic salbutamol and another commercial aerosol containing racemic salbutamol as the active ingredient. Results are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences (P>0.05) found in either the MMAD or FPF% between R-salbutamol and the other aerosol formulations. The GSD values, which reflect the collection efficiency of the impactor, showed no significant difference between groups (P>0.05).

Table 1.

Particle size distribution under cooling condition for four aerosol solutions.

| Sample | MMAD (μm) | FPF% | GSD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ventolin | 3.39±0.10 | 71.96±1.80 | 1.92±0.01 |

| DaFenKeChuang | 3.41±0.04 | 71.78±0.46 | 1.91±0.03 |

| R-Salbutamol | 3.28±0.20 | 72.81±4.10 | 1.95±0.03 |

| Racemic salbutamol | 3.32±0.18 | 71.97±3.47 | 1.96±0.03 |

Cooling condition: 5 °C.

Data are expressed as mean±SD, n=3.

3.4. The dose uniformity of delivery of R-salbutamol

The delivery rate and total amount of R-salbutamol delivered were evaluated following the specifications of preparations for nebulization as described in the EP. The breath simulator was connected with the nebulizer using an adult pattern to test. The amount of R-salbutamol inhaled into BRS 2000 was quantified with HPLC compared to racemic salbutamol and other commercial aerosols with racemic salbutamol as the active ingredient. The results are shown in Table 2. The concentration of the active ingredient in all aerosol solutions tested was 2.5 mg/mL. No significant difference was found between groups (P>0.05).

Table 2.

Dose uniformity for four inhalation solution.

| Sample | Active ingredient delivery rate (μg/s) | Total active ingredient delivered (mg) |

|---|---|---|

| Ventolin | 2.710±0.329 | 1.814±0.050 |

| DaFenKeChuang | 2.719±0.287 | 1.830±0.099 |

| R-Salbutamol | 2.704±0.232 | 1.851±0.357 |

| Racemin salbutamol | 2.727±0.072 | 1.777±0.125 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD, n=3.

The nebulizer user manual specifies that the solution volume in the cup should be between 2 and 8 mL. The solution in the cup would decrease gradually as it is atomized, which causes the aerosol to be mixed with more air when the volume is less than 2 mL. A dose-uniformity test can give us more information about the amount of active ingredient delivered. The active substance delivery rate was about 2.7 μg/s for those formulations. Total active substance delivered in 10 min was less than 2 mg in our results, while the solution volume was 3 mL at first, containing 7.5 mg active substance. The total active substance inhaled onto filters of BRS 2000 was 1.814, 1.830, 1.851 and 1.777 mg (mean value) for Ventolin, DaFenKeChuang, R-salbutamol solution and racemic salbutamol solution, respectively, which amounted to 24.19%, 24.40%, 24.67% and 23.69% of the total active substance in the cup. All recovery rates were less than 25%, indicating that the respiratory parameters and nebulizer greatly influenced the active substance inhaled.

Such a test might be indicative of fugitive droplet emission from nebulizers, which is a concern in some countries, after the SARS outbreaks that occurred in China during 2003. Other results from other patterns (children or neonate) can give some guidance for clinical applications because the efficacy of inhalers depended on patient compliance, formulation and device. The dose uniformity might be taken as a degree of reference for the patient's respiratory status.

Until recently, all inhalers in China were required only to evaluate the particles size distribution. The CFDA has not issued related guidance for the nebulizer. Results in other labs have proved that the particle size distribution of nebulizer, when determined by the impactor method, was greatly affected by the temperature36,37. It is of great importance to consider the control of temperature for nebulizer when the Chinese pharmacopoeia is revised and published in 2015. The further development of instruments for dose uniformity test is also needed.

3.5. The anti-asthmatic effect of inhaled R-salbutamol aerosol in vivo

Data analysis for in vitro studies has shown that the in-home formulation of R-salbutamol sulfate did not show any significant difference in particle size distribution and dose uniformity in comparison to the racemic formulation.

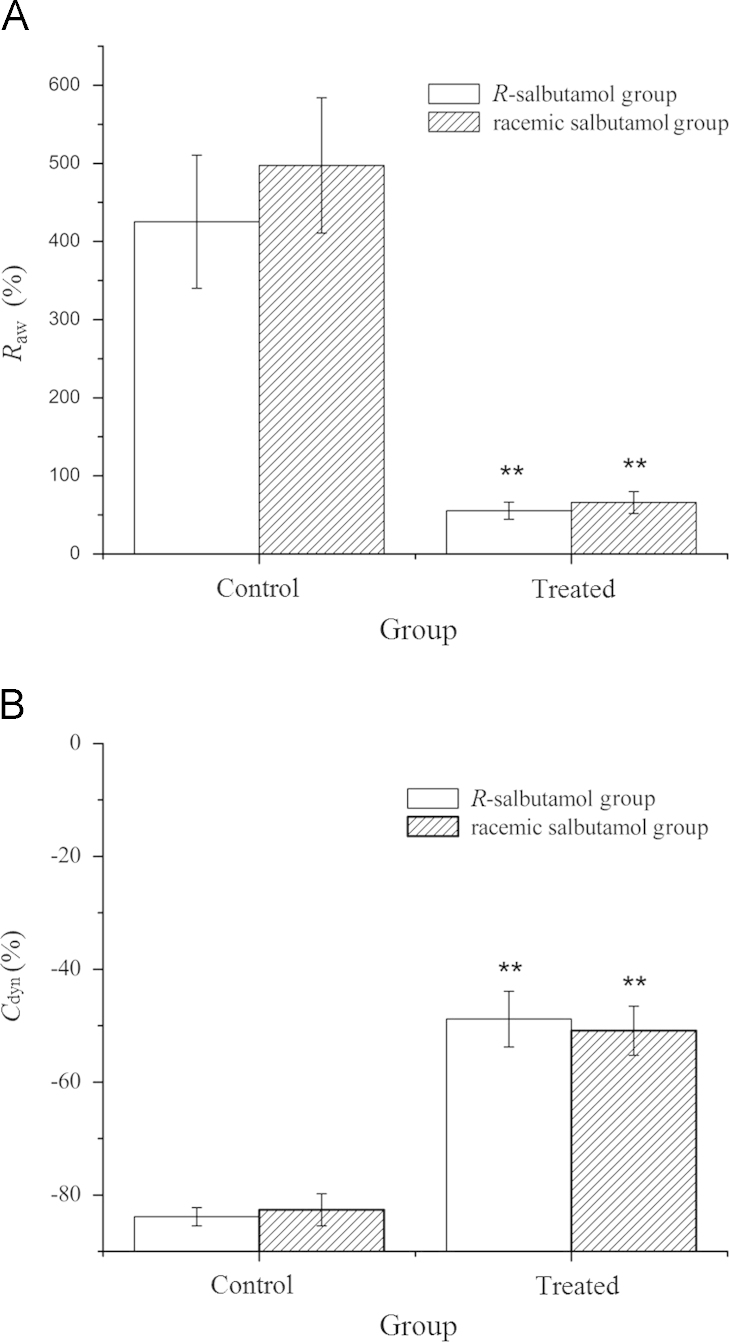

The anti-asthmatic effect of aerosol R-salbutamol was studied in guinea pigs with histamine-evoked asthma. There was a great asthmatic response evoked by histamine (15 μg/mL, 0.5 mL) indicated by an increase in airway resistance and decrease in dynamic compliance. The peak Raw and Cdyn during asthma response was 425.37±85.25% and −83.85±1.63%, respectively, compared with that of baseline values. However, when the animal was pretreated with inhaled R-salbutamol aerosol (0.2 mg/mL, 30 s), the increase of the peak Raw was 55.23±11.03% during histamine-evoked asthma, which was greatly diminished compared to no-drug treated; the peak Cdyn was −48.82±4.95%, which was also increased significantly (P<0.01). This indicated that the inhalation of R-salbutamol can significantly prevent asthma.

A similar test was conducted by giving a double dose of racemic salbutamol aerosol before the histamine challenge. The asthmatic responses were recorded and compared with the R-salbutamol group. The peak increase in Raw and peak decrease in Cdyn were 497.30±86.71% and −82.62±2.85%, respectively, from baseline value in control. However, the changes in Raw (65.87±14.05%) and Cdyn (−50.89±4.34%) from treated were greatly reduced after inhalation of racemic salbutamol (P<0.01). The above results indicated that the anti-asthmatic effects for a half-dose of R-salbutamol aerosol were similar to the effects of a full dose of racemic salbutamol aerosol when given by inhalation in guinea pigs. There was no statistical difference in the changes in either Raw or Cdyn between R-salbutamol and racemic salbutamol groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Effect of inhaling R-salbutamol and racemic salbutamol on Raw (A) and Cdyn (B). The animals were divided into two groups (each group has eight guinea pigs, 4 males and 4 females): I, inhaling saline (control) following R-salbutamol (0.2 mg/mL, 30 s) and II, inhaling saline (control) following racemic salbutamol (0.4 mg/mL, 30 s). The data are expressed as mean±SE, n=8. **P<0.01 vs. control group.

Results in our pharmacodynamic experiments proved that the efficacy of R-salbutamol was equivalent in comparison to racemic salbutamol when the concentration of solution was 0.2 and 0.4 mg/mL, respectively. The bronchodilatory effect of R-salbutamol and racemic salbutamol was compared in patients with asthma. These results support the concept that S-salbutamol might have detrimental effects on pulmonary function.

The improvement in FEV1 (Forced expiratory volume in one second, Characterization of the vital capacity) was similar for R-salbutamol (0.63 mg) and racemic salbutamol (2.5 mg) and greater than R-salbutamol at 1.25 mg38. Absorption from the gut was not determined in this study. The distribution of sulfotransferase, which metabolizes salbutamol, was very different between lung and gut.

After inhaling R-salbutamol, double absorption peaks on the plasma concentration versus time curves were observed in the majority of dogs, which was thought to be due to the result of combined gut and lung adsorption of R-salbutamol39. However, if subjects were co-administered oral activated charcoal which can prevent absorption from the gut, the plasma concentration-time profiles of R-salbutamol and S-salbutamol after inhalation showed the same trend with intravenous administration40. These indicated that a significant proportion of an inhaled dose was swallowed and then underwent the enantioselective presystemic metabolism observed following an oral dose, while no evidence of enantioselective metabolism of R-salbutamol in the lungs was found after inhaling racemic salbutamol40. Adverse effects of S-salbutamol may not be immediately obvious. Subjects in Nelson's research were not administered any materials, which can prevent the adsorption of gut. When they were treated by means of nebulization, part of the drug aerosol would be absorbed from the gut, and most of R-salbutamol would be metabolized more quickly than S-salbutamol, which causes the accumulation of S-enantiomer in humans after 28 days. This also explained why the efficacy of R-salbutamol 0.63 mg was similar with racemic salbutamol 2.5 mg, but no evaluation was carried out in vitro to compare the particle distribution and dose uniformity for the formulations used in this research.

The animal model used in these experiments completely avoids the influence of gut adsorption, as the aerosol was inhaled through tracheal intubation. Both airway resistance and dynamic compliance of lung were evaluated according to this approach. This method can be appropriate for the evaluation of β2-adrenoceptor agonists on the improvement of asthma between the single enantiomer and racemic mixture when no significant difference was found in in vitro experiments. While the anti-asthma effect was tested in an acute episode of the asthma model, further research remains to be carried out to validate the adverse effects of R-salbutamol sulfate and racemic salbutamol sulfate after long-term inhalation.

4. Conclusions

Our results show that this aerosol formulation R-salbutamol sulfate met all the requirements of the new EMA guidelines for nebulizer use. The R-salbutamol aerosol formulation showed the same potent anti-asthmatic effects as the racemic salbutamol formulation although at half the dose. It avoided the use of S-salbutamol, which has been shown to result in adverse effects. Therefore, this aerosol formulation of R-salbutamol sulfate may have therapeutic advantages in the control of asthma in comparison to aerosol formulations of racemic salbutamol sulfate which are currently commercially available in China.

Acknowledgments

We thank Key-Pharma Biomedical Inc. Dongguan, China, for the technical and financial support on this project. The study was supported by grant 10C26214404752 from small and mid-sized enterprise technology innovation fund management center of Science and Technology Department.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

References

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, Zahran HS, King M, Johnson CA., et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. 2012. Available from: 〈http:/www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db94.htm〉.

- 2.Lin JT, Su N, Liu GL, Yin KS, Zhou X, Shen HH, etal. The impact of concomitant allergic rhinitis on asthma control: a cross-sectional nation wide survey in China. J Asthma 2013 October 4. Available from: 10.3109/02770903.2013.840789 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Chen Z.H., Wang P.L., Shen H.H. Asthma research in China: a five-year review. Respirology. 2013;18 Suppl 3:S10–S19. doi: 10.1111/resp.12196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y.Z. Prevention and treatment of childhood asthma in China. World J Pediatr. 2005;1:85–87. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong J.G. Global initiative for asthma 2006. J Appl Clin Pediatr. 2007;22:1278–1280. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones B.P., Paul A. Management of acute asthma in the pediatric patient: an evidence-based review. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2013;10:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X.F., Hong J.G. Management of severe asthma exacerbation in children. World J Pediatr. 2011;7:293–301. doi: 10.1007/s12519-011-0325-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzoni L., Naef R., Chapman I.D., Morely J. Hyperresponsiveness of the airways following exposure of guinea-pigs to racemic mixtures and distomers of β2-selective sympathomimetics. Pulm Pharmacol. 1994;7:367–376. doi: 10.1006/pulp.1994.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Templeton A.G., Chapman I.D., Chilvers E.R., Morley J., Handley D.A. Effects of S-salbutamol on human isolated bronchus. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 1998;11:1–6. doi: 10.1006/pupt.1998.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal D.K., Ariyarathna K., Kelbe P.W. (S)-Albuterol activates pro-constrictory and pro-inflammatory pathways in human bronchial smooth muscle cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ameredes B.T., Calhoun W.J. Modulation of GM-CSF release by enantiomers of β-agonists in human airway smooth muscle. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chorley B.N., Li Y.H., Fang S.J., Park J.A., Adler K.B. (R)-albuterol elicits antiinflammatory effects in human airway epithelial cells via iNOS. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34:119–127. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0338OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho S.H., Hartleroad J.Y., Oh C.K. (S)-Albuterol increases the production of histamine and IL-4 in mast cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2001;124:478–484. doi: 10.1159/000053783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nigo Y.I., Yamashita M., Hirahara K., Shinnakasu R.M., Kimura M. Regulation of allergic airway inflammation through Toll-like receptor 4-mediated modification of mast cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2286–2291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510685103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walle U.K., Pesola G.R., Walle T. Stereoselective sulphate conjugation of salbutamol in humans: comparison of hepatic, intestinal and platelet activity. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;35:413–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmekel B., Rydberg I., Norlander B., Sjosward K.N., Ahlner J., Andersson R.G. Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of S-salbutamol after administration of the racemate in healthy volunteers. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:1230–1235. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13f04.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein D.A., Tan Y.K., Soldin S.J. Pharmacokinetics and absolute bioavailability of salbutamol in healthy adult volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;32:631–634. doi: 10.1007/BF02456001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeNicola L.K., Gayle M.O., Blake K.V. Drug therapy approaches in the treatment of acute severe asthma in hospitalised children. Paediatr Drugs. 2001;3:509–537. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200103070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomaszewski J., Rumore M.M. Stereoisomeric drugs: FDA's policy statement and the impact on drug development. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 1994;20:119–139. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tucker G.T. Chiral switches. The Lancet. 2000;355:1085–1087. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02047-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gradon L.R., Sosnowski T.R. Formation of particles for dry powder inhalers. Adv Powder Technol. 2013;3:509–537. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krebs S.E., Flood R.G., Peter J.R., Gerard J.M. Evaluation of a high-dose continuous albuterol protocol for treatment of pediatric asthma in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29:191–196. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182809b48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dennis J., Berg E., Sandell D., Kreher C., Karlssin M., Lamb P. European Pharmaceutical Aerosol Group (EPAG) nebulizer sub-team: assessment of proposed European Pharmacopoeial (Ph. Eur.) monograph Preparations for Nebulization. J Aerosol Med. 2007;20:40. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan C.X., Jiang W.M., Chen G.L., Wang L.D., Chen G., Shao H. Critical evaluation of determination methods of the particle size dry powder inhaler: a comparison of three impactors. Chin J Pharm Anal. 2011;31:1296–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asmus M.J., Hendeles L. Levalbuterol nebulizer solution: is it worth five times the cost of albuterol? Pharmacotherapy. 2000;20:123–129. doi: 10.1592/phco.20.3.123.34776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vargas M.H., Sommer B., Bazán-Perkins B., Montano L.M. Airway responsiveness measured by barometric plethysmography in guinea pigs. Vet Res Commun. 2010;34:589–596. doi: 10.1007/s11259-010-9430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Begin R., Renzetti A.D., Bigler A.H., Wantanabe S. Flow and age dependence of airway closure and dynamic compliance. J Appl Physiol. 1975;38:199–207. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.38.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tzou T.Z., Pachuta R.R., Coy R.B., Robert K.S. Drug form selection in albuterol-containing metered-dose inhaler formulations and its impact on chemical and physical stability. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86:1352–1357. doi: 10.1021/js970225g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mälkki L., Tammilehto S. Decomposition of salbutamol in aqueous solutions. I. The effect of pH, temperature and drug concentration. Int J Pharm. 1990;63:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mälkki-Laine L., Purra K., Kähkönen K., Thammilehto S. Decomposition of salbutamol in aqueous solutions. II. The effect of buffer species, pH, buffer concentration and antioxidants. Int J Pharm. 1995;117:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Świercz R., Hałatek T., Wąsowicz W., Kur B., Grzelinska Z., Majchere K.W. Pulmonary irritation after inhalation exposure to benzalkonium chloride in rats. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2008;21:157–163. doi: 10.2478/v10001-008-0020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell J.P., Nagel M.W. Particle size analysis of aerosols from medicinal inhalers. KONA. 2004;22:32–65. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shekunov B.Y., Chattopadhyay P., Tong H.H., Chow A.H. Particle size analysis in pharmaceutics: principles, methods and applications. Pharm Res. 2007;24:203–227. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loffert D.T., Ikle D., Nelson H.S. A comparison of commercial jet nebulizers. Chest. 1994;6:788–792. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.6.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hess D., Fisher D., Williams P., Pooler S., Kacmarek R.M. Medication nebulizer performance effects of diluent volume, nebulizer flow, and nebulizer brand. Chest. 1996;110:98–505. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.2.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou Y., Ahuja A., Irvin C.M., Kracko D.A., Mcdonald J.D., Cheng Y.S. Medical nebulizer performance: effects of cascade impactor temperature. Respir care. 2005;50:1077–1082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dennis J., Berg E., Sandell D., Ali A., Lamb P., Tservistas M. Cooling the NGI-an approach to size a nebulised aerosol more accurately. Pharmeur Sci Notes. 2008;1:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson H.S., Bensch G., Pleskow W.W., DiSantostefano R., DgGraw S., Reasner D.S. Improved bronchodilation with levalbuterol compared with racemic albuterol in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102:943–952. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(98)70332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auclair B., Wainer I.W., Fried K., Koch P., Jerussi T.P., Ducharme M.P. A population analysis of nebulized (R)-albuterol in dogs using a novel mixed gut-lung absorption PK-PD model. Pharm Res. 2000;17:1228–1235. doi: 10.1023/a:1026466730347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ward J.K., Dow J., Dallow N., Eynott P., Milleri S., Ventresca G.P. Enantiomeric disposition of inhaled, intravenous and oral racemic-salbutamol in man–no evidence of enantioselective lung metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49:15–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00102.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]