Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease that disproportionately affects African Americans and other minorities in the USA. Public health attention to SLE has been predominantly epidemiological. To better understand the effects of this cumulative disadvantage and ultimately improve the delivery of care, specifically in the context of SLE, we propose that more research attention to the social determinants of SLE is warranted and more transdisciplinary approaches are necessary to appropriately address identified social determinants of SLE. Further, we suggest drawing from the chronic care model (CCM) for an understanding of how community-level factors may exacerbate disparities explored within social determinant frameworks or facilitate better delivery of care for SLE patients. Grounded in social determinants of health (SDH) frameworks and the CCM, this paper presents issues relative to accessibility to suggest that more transdisciplinary research focused on the role of place could improve care for SLE patients, particularly the most vulnerable patients. It is our hope that this paper will serve as a springboard for future studies to more effectively connect social determinants of health with the chronic care model and thus more comprehensively address adverse health trajectories in SLE and other chronic conditions.

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic inflammatory rheumatic disease that is characterized by autoantibody production and multiple organ system involvement, including a high prevalence of polyarthritis [1–4]. In the United States, over the past four decades, SLE incidence has increased and claims one of the highest mortality rates among rheumatic diseases [5, 6]. SLE incidence, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality are all much higher among minorities than whites in the United States. SLE incidence rates among African American women are 3 to 4 times higher than white women, while men have much lower rates than women in general [7], and Hispanics, Asians, and Native Americans are also more likely to develop lupus than non-Hispanic Whites [8, 9]. The overall spectrum of SLE clinical presentation is similar across different ethnic groups, but there appears to be some differences in the autoantibody profile, frequency of certain specific disease complications, and the severity and overall prognosis of the condition [10]. For example, there is cumulative evidence that lupus nephritis (LN)/renal disease is more prevalent in African and Hispanic Americans, as well as Chinese and other Asians [10–13]. It has also been shown that poverty negatively impacts disease outcomes for minority SLE patients [14–21]. Additionally, SLE patients often endure high degrees of psychological symptoms including anxiety, depression, mood disorders, and decreased health-related quality of life [12, 22–28]. These trends may be more pronounced in African and Hispanic Americans, who have been historically exposed to a unique set of risk factors that lead to a pattern of cumulative disadvantage over time [29–41].

Public health attention to SLE has been predominantly epidemiological [6], documenting mortality and morbidity of SLE and potential effects of environmental exposures [42–45]. SLE research has not traditionally embraced models around the social determinants of health and chronic care simultaneously. To better understand the effects of this cumulative disadvantage and ultimately improve the delivery of care, specifically in the context of SLE, we propose that such approaches are necessary to improve care for SLE patients, particularly for those at highest risk. Further, we suggest drawing from the chronic care model (CCM) for an understanding of how community-level factors may exacerbate disparities explored within social determinant frameworks or facilitate better delivery of care for SLE patients.

Grounded in SDH frameworks and the CCM, this paper presents issues relative to accessibility to suggest that more transdisciplinary research focused on the role of place could improve care for SLE patients, particularly the most vulnerable patients. An approach that comprehensively examines both community- and individual-level social determinants contributing to negative impacts of SLE could improve clinical knowledge (e.g., recruitment for interventions, clinical trials) and assist in improving care for those disproportionately impacted by SLE (e.g., racial and ethnic minorities).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Determinants of Health Framework

Originally coined by Whitehead and Dahlgren [46], the social determinants of health (SDH) framework takes into account the social, environmental, and economic conditions that impact individual health outcomes (see Table 1). This model considers the roles of both macro- and microlevel factors in population health [46–48].

Table 1.

Whitehead and Dahlgren's social determinants of health framework components.

| Components | Examples |

|---|---|

| (1) General socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions | Proximity to industrialized, toxic facilities |

| (2) Living and working conditions | Agriculture and food production; education; work environment; unemployment; water and sanitation; health care services; housing |

| (3) Social and community networks | Social capital networks; civic organizations |

| (4) Individual lifestyle factors | Smoking behavior; sexual risk factors |

| (5) Age, sex, and constitutional factors | Biological determinants |

Expanding on Whitehead and Dahlgren's model, Robinson's SDH framework considers the importance of community and race/ethnicity to individual health outcomes [49]. The model adheres to principles and guided activities related to surveillance, research, and program and policy development, such as (a) heterogeneity, diversity, and inclusivity; (b) a participatory approach; (c) development of trust; (d) community, race, and ethnicity; (e) community competence, development, and prevention; and (f) comprehensiveness [49]. Application of this model to SLE patients, therefore, requires activities that are aimed at not only understanding community influences but also producing activities that are participatory in addressing the needs of SLE patients.

2.2. Chronic Care Model

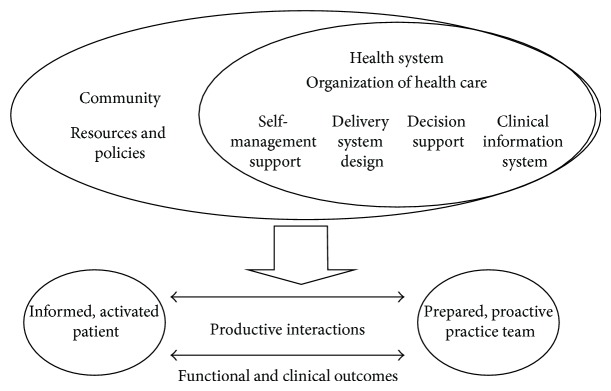

Complementing an SDH framework, Wagner's chronic care model [50, 51] (CCM) is a widely accepted model for understanding how to best organize the delivery of care to improve patient health outcomes, through six interrelated system changes that aim to make care more patient-centered and oriented around evidence-based practices (see Figure 1). The main aim of the CCM is to transform daily care for patients with chronic illnesses from acute/ambulatory treatments to more proactive approaches, with increased attention to primary care and delivery of care. Adaptation of this model results in a variety of approaches, such as effective team care and planned interactions, self-management support bolstered by more effective use of community resources, integrated decision support, and patient registries and other supportive information technology [51]. The model supports improvements in care delivery that consider community resources and maximize usage of these resources. The model has been applied in various populations and has been effective in treating and caring for the chronically ill [52–55].

Figure 1.

Chronic care model.

One such strategy has been the implementation of self-management techniques for rheumatic, particularly SLE, patients. Over the past 25 years, research has demonstrated the effectiveness of arthritis self-management education delivered by small-group, home study, computer, and Internet modalities [36, 56–72]. Such programs have demonstrated significant improvements in health distress, self-reported global health, and activity limitation, with trends toward improvement in self-efficacy and mental stress management [41, 56, 73–77]. Consequently, numerous national agencies have recommended arthritis self-management education to complement medical care [25, 43–47]. However, a study utilizing CDSMP reported that less than 50% of a closed eligible population participated, even when Internet and small-group programs were offered repeatedly over many years [36, 62, 65, 71, 78–82]. Understanding travel impediments and other social determinants of SLE could begin to fill such gaps.

Drawing from the CCM for an understanding of how community-level factors may exacerbate disparities or facilitate better delivery of care for SLE patients within SDH frameworks is based on a paradigm shift from the current model of dealing with acute care [83] issues to a system that is prevention based [84–92]. The premise of the CCM is that quality care for the chronically ill is not delivered in isolation and can be enhanced by community resources, self management support, delivery system redesign, decision support, clinical information systems, and organizational support working in tandem to enhance patient-provider interactions (see Figure 1) [92].

2.3. Accessibility/Travel

Examinations of health-related travel and accessibility draw our discussion of connecting SDH frameworks and the CCM together. We reviewed scientific literature that has examined travel as a potential barrier to accessing care to assess trends, discrepancies, strengths, and limitations of current attention to social determinants impacting the lives of SLE patients.

Accessibility to care is an important component in understanding the influence of social determinants of health, and it has been addressed in health service policy research for several years [93, 94]. Considering travel, which influences patient access to healthcare, is critical to fully understand accessibility. This line of research can be extremely useful when considering the geographical availability of rheumatologists and corresponding patient needs. Research with SLE patients has suggested that economic consequences and costs of illness can negatively impact disease activity/damage and SLE patients' ability to successfully manage their disease [17, 95]. Many studies have documented racial disparities among SLE patients, but there has been little in-depth research on the social dimensions that shape these disparities, particularly with regard to travel impediments that might influence accessibility [96–108].

We were able to identify one study that specifically addressed health-related travel among SLE patients. Gillis and colleagues (2007) evaluated the association between Medicaid insurance and distance traveled by patients to treating physicians and health care utilization for SLE patients [109]. Using residential address information and primary SLE provider address information, researchers calculated the distance between the two locations for each participant, using MapQuest. They found that Medicaid patients, particularly those under the care of a rheumatologist, traveled longer distances to their primary SLE providers [109]. Medicaid patients were also more likely to be seen by a general practitioner or in the emergency room (ER) for SLE complications; travel impediments to accessing rheumatologists could have contributed to this statistic [109]. This research suggests that understanding health system infrastructure and community resources is a plausible step toward improving accessibility, potentially ensuring improved care for SLE patients, and decreasing health care costs associated with ER overuse.

In our own work, a validated psychosocial stress intervention was piloted among a cohort of African American SLE patients participating in an SLE database project at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). During the course of the Balancing Lupus Experiences with Stress Strategies (BLESS) study, it became apparent that travel issues were preventing the full participation of the MUSC cohort. During followup phone calls for this project, many participants relayed that they could not participate in all aspects of the intervention because of complications related to travel. Some identified having to utilize Medicaid supported travel that required prior scheduling well in advance, but even this type of transportation was not completely reliable. Others identified having to travel long distances, which required advance planning because of reliance on family members or friends to assist with transport (unpublished observations). This information contributed to our knowledge concerning nonadherence and substantiated a need for further investigation of these issues. Specifically, this knowledge provided a foundation to investigate whether travel burden contributed to stress that may also impact the effectiveness of disease self-management programs. In that subsequent investigation, we identified four major areas of concern with respect to travel burden in accessing their rheumatologists: general travel issues; competing priorities; social/economic support challenges; and challenges surrounding general health (unpublished observations).

All of these findings emphasize the importance of exploring the specific factors that limit and motivate the participation of a vulnerable disease population in critical healthcare and research activities.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, this review of SDH frameworks, the CCM, and the case of accessibility and travel issues in the context of SLE reveal that much more work can be done to improve care for SLE patients. Transdisciplinary approaches and research efforts could bring together several innovative methods for better addressing the complex issues faced by SLE patients. Further investigation of exactly how current approaches have been limited and the implications for disease manifestations and treatment are warranted to guide future SLE research. This would help to assess the appropriateness of focusing more broadly on “upstream” influences as a way to improve quality of life for SLE patients by exploring instances where focusing on upstream influences has improved care outcomes. Thus, we would more comprehensively elucidate the need for population health approaches rooted in the social determinants of health framework while setting the stage for connecting it to a biomedical framework that is widely accepted among physicians and medical researchers. By this, we can suggest not only continuing traditional models of biomedical research but also producing extrapolations regarding how broad social influences impact the lives of SLE patients.

Our review suggests that more research is needed to expand the scope of barriers of SLE to include social determinants such as accessibility and health-related travel. GIS research methods should be used in future research to begin to fill this knowledge gap. Thus, drawing from geography research methods and theories, researchers attempting to better understand place-related disparities could benefit greatly from transdisciplinary intervention activities that include research areas that explore the impact of travel on SLE patients, especially considering the geographic coverage of clinical trials studying SLE. It is our hope that this paper will serve as a springboard for future studies to more effectively connect social determinants of health with the chronic care model and thus more comprehensively address adverse health trajectories in SLE and other chronic conditions.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this article.

References

- 1.Ward M. M., Pyun E., Studenski S. Causes of death in systemic lupus erythematosus: long-term followup of an inception cohort. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1995;38(10):1492–1499. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trager J., Ward M. M. Mortality and causes of death in systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2001;13(5):345–351. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urowitz M. B., Gladman D. D., Abu-Shakra M., Farewell V. T. Mortality studies in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a single center. III: improved survival over 24 years. Journal of Rheumatology. 1997;24(6):1061–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urowitz M. B., Feletar M., Bruce I. N., Ibañez D., Gladman D. D. Prolonged remission in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Rheumatology. 2005;32(8):1467–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uramoto K. M., Michet C. J., Jr., Thumboo J., Sunku J., O'Fallon W. M., Gabriel S. E. Trends in the incidence and mortality of systemic lupus erythematosus, 1950–1992. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1999;42(1):46–50. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<46::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel S. E., Michaud K. Epidemiological studies in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and comorbidity of the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2009;11(3, article 229) doi: 10.1186/ar2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demas K. L., Costenbader K. H. Disparities in lupus care and outcomes. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 2009;21(2):102–109. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328323daad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alarcón G. S., Beasley T. M., Roseman J. M., et al. Ethnic disparities in health and disease: the need to account for ancestral admixture when estimating the genetic contribution to both (LUMINA XXVI) Lupus. 2005;14(10):867–868. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2184xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oates J. C., Levesque M. C., Hobbs M. R., et al. Nitric oxide synthase 2 promoter polymorphisms and systemic lupus erythematosus in African-Americans. Journal of Rheumatology. 2003;30(1):60–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cooper G. S., Parks C. G., Treadwell E. L., et al. Differences by race, sex and age in the clinical and immunologic features of recently diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus patients in the southeastern United States. Lupus. 2002;11(3):161–167. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu161oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alarcón G. S., McGwin G., Jr., Petri M., et al. Time to renal disease and end-stage renal disease in PROFILE: a multiethnic lupus cohort. PLoS Medicine. 2006;3(10):1949–1956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030396.e396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petri M. Lupus in Baltimore: evidence-based “clinical pearls” from the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. Lupus. 2005;14(12):970–973. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2230xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bastian H. M., Roseman J. M., McGwin G., Jr., et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XII. Risk factors for lupus nephritis after diagnosis. Lupus. 2002;11(3):152–160. doi: 10.1191/0961203302lu158oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alarcon G. S., McGwin G., Jr., Bastian H. M., et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. VIII. Predictors of early mortality in the LUMINA cohort. Arthritis Care and Research. 2001;45(3):191–202. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)45:2<191::AID-ANR173>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yazdany J., Gillis J. Z., Trupin L., et al. Association of socioeconomic and demographic factors with utilization of rheumatology subspecialty care in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care and Research. 2007;57(4):593–600. doi: 10.1002/art.22674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duvdevany I., Cohen M., Minsker-Valtzer A., Lorber M. Psychological correlates of adherence to self-care, disease activity and functioning in persons with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2011;20(1):14–22. doi: 10.1177/0961203310378667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu T. Y., Tam L. S., Li E. K. Cost-of-illness studies in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Arthritis Care and Research. 2011;63(5):751–760. doi: 10.1002/acr.20410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mau W., Listing J., Huscher D., et al. Employment across chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases and comparison with the general population. Journal of Rheumatology. 2005;32(4):721–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke A. E., Esdaile J. M., Bloch D. A., Lacaille D., Danoff D. S., Fries J. F. A Canadian study of the total medical costs for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and the predictors of costs. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1993;36(11):1548–1559. doi: 10.1002/art.1780361109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Partridge A. J., Karlson E. W., Daltroy L. H., et al. Risk factors for early work disability in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a multicenter study. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1997;40(12):2199–2206. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell R., Jr., Cooper G. S., Gilkeson G. S. The impact of systemic lupus erythematosus on employment. Journal of Rheumatology. 2009;36(11):2470–2475. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoll T., Gordon C., Seifert B., et al. Consistency and validity of patient administered assessment of quality of life by the MOS SF-36; Its association with disease activity and damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Rheumatology. 1997;24(8):1608–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobkin P. L., Fortin P. R., Joseph L., Esdaile J. M., Danoff D. S., Clarke A. E. Psychosocial contributors to mental and physical health in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care and Research. 1998;11(1):23–31. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zak M., Pedersen F. K. Juvenile chronic arthritis into adulthood: a long-term follow-up study. Rheumatology. 2000;39(2):198–204. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruperto N., Buratti S., Duarte-Salazar C., et al. Health-related quality of life in juvenile-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and its relationship to disease activity and damage. Arthritis Care and Research. 2004;51(3):458–464. doi: 10.1002/art.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gutiérrez-Suárez R., Pistorio A., Cespedes Cruz A., et al. Health-related quality of life of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis coming from 3 different geographic areas. The PRINTO multinational quality of life cohort study. Rheumatology. 2007;46(2):314–320. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toloza S. M. A., Jolly M., Alarcón G. S. Quality-of-life measurements in multiethnic patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: cross-cultural issues. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2010;12(4):237–249. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnado A., Wheless L., Meyer A. K., Gilkeson G. S., Kamen D. L. Quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) compared with related controls within a unique African American population. Lupus. 2012;21(5):563–569. doi: 10.1177/0961203311426154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams D. R. The health of men: structured Inequalities and opportunities. The American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(5):724–731. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt S. B., Williams D. R., Calvin R., Henderson F. C., Walker E. R., Winters K. Racism and cardiovascular disease in African Americans. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2003;325(6):315–331. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carroll G. Mundane extreme environmental stress and African American families: a case for recognizing different realities. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1998;29(2):271–284. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hertzman C., Wiens M. Child development and long-term outcomes: a population health perspective and summary of successful interventions. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43(7):1083–1095. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams D. R., Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cattell V. Poor people, poor places, and poor health: the mediating role of social networks and social capital. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52(10):1501–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Donnell M. Health-promotion behaviors that promote self-healing. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2004;10(supplement 1):S49–S60. doi: 10.1089/1075553042245809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaab J., Sonderegger L., Scherrer S., Ehlert U. Psychoneuroendocrine effects of cognitive-behavioral stress management in a naturalistic setting: a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(4):428–438. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greco C. M., Rudy T. E., Manzi S. Effects of a stress-reduction program on psychological function, pain, and physical function of systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care and Research. 2004;51(4):625–634. doi: 10.1002/art.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dobkin P. L., da Costa D., Joseph L., et al. Counterbalancing patient demands with evidence: results from a Pan-Canadian randomized clinical trial of brief supportive-expressive group psychotherapy for women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24(2):88–99. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2402_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bijlani R. L., Vempati R. P., Yadav R. K., et al. A brief but comprehensive lifestyle education program based on yoga reduces risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2005;11(2):267–274. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coalition T. W. L. Spring Luncheon. Buffalo, NY, USA: State University of New York at Buffalo; 2005. Sisters! Understand your heart, body, and environment. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lorig K., Ritter P. L., Plant K. A disease-specific self-help program compared with a generalized chronic disease self-help program for arthritis patients. Arthritis Care and Research. 2005;53(6):950–957. doi: 10.1002/art.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayes M. D. Epidemiologic studies of environmental agents and systemic autoimmune diseases. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1999;107(5):743–748. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s5743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper G. S., Parks C. G. Occupational and environmental exposures as risk factors for systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Rheumatology Reports. 2004;6(5):367–374. doi: 10.1007/s11926-004-0011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarzi-Puttini P., Atzeni F., Iaccarino L., Doria A. Environment and systemic lupus erythematosus: an overview. Autoimmunity. 2005;38(7):465–472. doi: 10.1080/08916930500285394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper G. S., Wither J., Bernatsky S., et al. Occupational and environmental exposures and risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: silica, sunlight, solvents. Rheumatology. 2010;49(11):2172–2180. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whitehead M., Dahlgren G. What can be done about inequalities in health? The Lancet. 1991;338(8774):1059–1063. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91911-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Whitehead M., Dahlgren G., Evans T. Equity and health sector reforms: can low-income countries escape the medical poverty trap? The Lancet. 2001;358(9284):833–836. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05975-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McIntyre D., Thiede M., Dahlgren G., Whitehead M. What are the economic consequences for households of illness and of paying for health care in low- and middle-income country contexts? Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(4):858–865. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson R. G. Community development model for public health applications: overview of a model to eliminate population disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6(3):338–346. doi: 10.1177/1524839905276036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner E. H., Austin B. T., Davis C., Hindmarsh M., Schaefer J., Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coleman K., Austin B. T., Brach C., Wagner E. H. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Toole T. P., Buckel L., Bourgault C., et al. Applying the chronic care model to homeless veterans: effect of a population approach to primary care on utilization and clinical outcomes. The American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(12):2493–2499. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.179416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lovell M., Myers K., Forbes T. L., Dresser G., Weiss E. Peripheral arterial disease: application of the chronic care model. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2011;29(4):147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jvn.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sack C., Phan V. A., Grafton R., et al. A chronic care model significantly decreases costs and healthcare utilisation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2012;6(3):302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Drewes H. W., Steuten L. M. G., Lemmens L. C., et al. The effectiveness of chronic care management for heart failure: meta-regression analyses to explain the heterogeneity in outcomes. Health Services Research. 2012;47(5):1926–1959. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lorig K., Lubeck D., Kraines R. G. Outcomes of self-help education for patients with arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1985;28(6):680–685. doi: 10.1002/art.1780280612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lorig K. R., Ritter P. L., Laurent D. D., Fries J. F. Long-term randomized controlled trials of tailored-print and small-group arthritis self-management interventions. Medical Care. 2004;42(4):346–354. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000118709.74348.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lorig K. R., Ritter P. L., Laurent D. D., Plant K. The internet-based arthritis self-management program: a one-year randomized trial for patients with arthritis or fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care and Research. 2008;59(7):1009–1017. doi: 10.1002/art.23817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goeppinger J., Arthur M. W., Baglioni A. J., Jr., Brunk S. E., Brunner C. M. A reexamination of the effectiveness of self-care education for persons with arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1989;32(6):706–716. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greco C. M., Rudy T. E., Manzi S. Effects of a stress-reduction program on psychological function, pain, and physical function of systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care and Research. 2004;51(4):625–634. doi: 10.1002/art.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fries J. F., Carey C., Mcshane D. J. Patient education in arthritis: randomized controlled trial of a mail-delivered program. Journal of Rheumatology. 1997;24(7):1378–1383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Austin J. S., Maisiak R. S., Macrina D. M., Heck L. W. Health outcome improvements in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus using two telephone counseling interventions. Arthritis Care and Research. 1996;9(5):391–399. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199610)9:5<391::aid-anr1790090508>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carter E. L., Nunlee-Bland G., Callender C. A patient-centric, provider-assisted diabetes telehealth self-management intervention for urban minorities. Perspectives in Health Information Management. 2011;8, article 1b [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Derose S. F., Nakahiro R. K., Ziel F. H. Automated messaging to improve compliance with diabetes test monitoring. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2009;15(7):425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edworthy S. M., Dobkin P. L., Clarke A. E., et al. Group psychotherapy reduces illness intrusiveness in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Rheumatology. 2003;30(5):1011–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franklin V. L., Waller A., Pagliari C., Greene S. A. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabetic Medicine. 2006;23(12):1332–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hanauer D. A., Wentzell K., Laffel N., Laffel L. M. Computerized automated reminder diabetes system (CARDS): E-mail and SMS cell phone text messaging reminders to support diabetes management. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics. 2009;11(2):99–106. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Juzang I., Fortune T., Black S., Wright E., Bull S. A pilot programme using mobile phones for HIV prevention. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2011;17(3):150–153. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.091107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maisiak R., Austin J. S., West S. G., Heck L. The effect of person-centered counseling on the psychological status of persons with systemic lupus erythematosus or rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Care and Research. 1996;9(1):60–66. doi: 10.1002/art.1790090111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Brien G., Lazebnik R. Telephone call reminders and attendance in an adolescent clinic. Pediatrics. 1998;101(6, article E6) doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pena-Robichaux V., Kvedar J. C., Watson A. J. Text messages as a reminder aid and educational tool in adults and adolescents with atopic dermatitis: a pilot study. Dermatology Research and Practice. 2010;2010:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2010/894258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bijlani R. L., Vempati R. P., Yadav R. K., et al. A brief but comprehensive lifestyle education program based on yoga reduces risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2005;11(2):267–274. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barlow J. H., Turner A. P., Wright C. C. A randomized controlled study of the arthritis self-management programme in the UK. Health Education Research. 2000;15(6):665–680. doi: 10.1093/her/15.6.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brady T. J., Kruger J., Helmick C. G., Callahan L. F., Boutaugh M. L. Intervention programs for arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. Health Education and Behavior. 2003;30(1):44–63. doi: 10.1177/1090198102239258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lorig K., Holman H. Arthritis self-management studies: a twelve-year review. Health Education Quarterly. 1993;20(1):17–28. doi: 10.1177/109019819302000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lorig K. R., Mazonson P. D., Holman H. R. Evidence suggesting that health education for self-management in patients with chronic arthritis has sustained health benefits while reducing health care costs. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1993;36(4):439–446. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kruger J. M. S., Helmick C. G., Callahan L. F., Haddix A. C. Cost-effectiveness of the arthritis self-help course. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158(11):1245–1249. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.11.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hochberg M. C., Altman R. D., Brandt K. D., et al. Guidelines for the medical management of osteoarthritis. Part II. Osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1995;38(11):1541–1546. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goeppinger J., Armstrong B., Schwartz T., Ensley D., Brady T. J. Self-management education for persons with arthritis: managing comorbidity and eliminating health disparities. Arthritis Care and Research. 2007;57(6):1081–1088. doi: 10.1002/art.22896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Haupt M., Millen S., Jänner M., Falagan D., Fischer-Betz R., Schneider M. Improvement of coping abilities in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2005;64(11):1618–1623. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.029926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.De Abreu M. M., Gafni A., Ferraz M. B. Development and testing of a decision board to help clinicians present treatment options to lupus nephritis patients in Brazil. Arthritis Care and Research. 2009;61(1):37–45. doi: 10.1002/art.24368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bruce B., Lorig K., Laurent D. Participation in patient self-management programs. Arthritis Care and Research. 2007;57(5):851–854. doi: 10.1002/art.22776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Louis-Jacques J., Samples C. Caring for teens with chronic illness: risky business? Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2011;23(4):367–372. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283481101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wagner E. H., Austin B. T., Von Korff M. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Managed Care Quarterly. 1996;4(2):12–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wagner E. H., Austin B. T., Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74(4):511–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bodenheimer T., Lorig K., Holman H., Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bodenheimer T., Wagner E. H., Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(14):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bodenheimer T., Wagner E. H., Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, Part 2. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288(15):1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wagner E. H. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. British Medical Journal. 2000;320(7234):569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wagner E. H., Glasgow R. E., Davis C., et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement. 2001;27(2):63–80. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(01)27007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wagner E. H., Grothaus L. C., Sandhu N., et al. Chronic care clinics for diabetes in primary care: a system-wide randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(4):695–700. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Glasgow R. E., Orleans C. T., Wagner E. H. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Milbank Quarterly. 2001;79(4):579–612. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Penchansky R., Thomas J. W. The concept of access. Definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Medical Care. 1981;19(2):127–140. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Guagliardo M. F. Spatial accessibility of primary care: concepts, methods and challenges. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2004;3, article 3 doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Alarcon G. S., McGwin G., Jr., Bartolucci A. A., et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. IX. Differences in damage accrual. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2001;44(12):2797–2806. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2797::aid-art467>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mullins C. D., Blatt L., Gbarayor C. M., Yang H.-W. K., Baquet C. Health disparities: a barrier to high-quality care. The American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2005;62(18):1873–1882. doi: 10.2146/ajhp050064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Loftin W. A., Barnett S. K., Bunn P. S., Sullivan P. Recruitment and retention of rural African Americans in diabetes research: lessons learned. Diabetes Educator. 2005;31(2):251–259. doi: 10.1177/0145721705275517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shaya F. T., Gbarayor C. M., Huiwen Keri Yang H. K. Y., Agyeman-Duah M., Saunders E. A perspective on African American participation in clinical trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2007;28(2):213–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Powers B. J., King J. L., Ali R., et al. The cholesterol, hypertension, and glucose education (CHANGE) study for African Americans with diabetes: study design and methodology. The American Heart Journal. 2009;158(3):342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tang T. S., Funnell M. M., Brown M. B., Kurlander J. E. Self-management support in “real-world” settings: an empowerment-based intervention. Patient Education and Counseling. 2010;79(2):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Blackwell C. S., Foster K. A., Isom S., et al. Healthy living partnerships to prevent diabetes: recruitment and baseline characteristics. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2011;32(1):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gadegbeku C. A., Stillman P. K., Huffman M. D., Jackson J. S., Kusek J. W., Jamerson K. A. Factors associated with enrollment of African Americans into a clinical trial: results from the African American study of kidney disease and hypertension. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2008;29(6):837–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mosley-Williams A., Lumley M. A., Gillis M., Leisen J., Guice D. Barriers to treatment adherence among African American and white women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care and Research. 2002;47(6):630–638. doi: 10.1002/art.10790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Uribe A. G., Alarcón G. S., Sanchez M. L., et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XVIII. Factors predictive of poor compliance with study visits. Arthritis Care and Research. 2004;51(2):258–263. doi: 10.1002/art.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mirotznik J., Ginzler E., Zagon G., Baptiste A. Using the health belief model to explain clinic appointment-keeping for the management of a chronic disease condition. Journal of Community Health. 1998;23(3):195–210. doi: 10.1023/A:1018768431574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gladman D. D., Koh D.-R., Urowitz M. B., Farewell V. T. Lost-to-follow-up study in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Lupus. 2000;9(5):363–367. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Petri M., Perez-Gutthann S., Longenecker J. C., Hochberg M. Morbidity of systemic lupus erythematosus: role of race and socioeconomic status. Pediatric Nephrology. 1991;4(4):p. 406. doi: 10.1007/BF00869752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jones P. K., Jones S. L., Katz J. A randomized trial to improve compliance in urinary tract infection patients in the emergency department. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 1990;19(1):16–20. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)82133-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gillis J. Z., Yazdany J., Trupin L., et al. Medicaid and access to care among persons with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care and Research. 2007;57(4):601–607. doi: 10.1002/art.22671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]