Abstract

Objective

Examine factors implicated in gestational weight gain (GWG) in low-income overweight and obese women.

Design

Qualitative study.

Setting

Community-based perinatal center.

Participants

8 focus groups with women (Black=48%, White non-Hispanic=41%, Hispanic=10%) in the first half of (n=12) and last half of pregnancy (n=10), or post-partum (n=7); 2 with obstetrician-gynecologists (OB-GYNs) (n=9).

Phenomenon of Interest

Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating and GWG within different levels of the Social Ecological Model (SEM), e.g. intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, etc.

Analysis

Coding guide was based on the SEM. Transcripts were coded by 3 researchers for common themes. Thematic saturation was reached.

Results

At an intrapersonal level, knowledge/skills and cravings were the most common barriers. At an interpersonal level, family and friends were most influential. At an organizational level, the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program and clinics were influential. At the community level, lack of transportation was most frequently discussed. At a policy level, complex policies and social stigma surrounding WIC were barriers. There was consensus that ideal intervention approaches would include peer-facilitated support groups with information from experts. OB-GYNs felt uncomfortable counseling patients about GWG due to time constraints, other priorities, and lack of training.

Conclusions and Implications

There are multi-level public health opportunities to promote healthy GWG. Better communication between nutrition specialists and OB-GYNs is needed.

Keywords: gestational weight gain, Overweight, Obesity

INTRODUCTION

Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is a public health concern. Sixty percent of overweight (BMI 25–29) and 45% of obese (BMI ≥30) women gain weight during pregnancy in excess of the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) recommendations.1,2 Current suggestions for total weight gain are 28–40 lb. for BMI<18.5, 25–35 lb. for BMI 18.5–24.9, 15–25 lb. for BMI 25.0–29.9, and 11–20 lb. for BMI ≥30.0.2 Women who gain excess gestational weight have increased risk of postpartum weight retention and developing diabetes and cardiovascular disease, have increased risk for cancer and mortality, and transmit risk to their offspring.3–7 Excess gestational weight gain (GWG) increases the risk of complications for newborns, including neonatal seizures, meconium aspiration syndrome, low Apgar scores, and large-for-gestational age (LGA), along with risks for overweight/obesity and adverse cardio-metabolic profile in childhood.8–11 Overweight and obese pregnant women experience higher rates of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, fetal macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, cesarean delivery, and intrauterine fetal death compared to their normal weight counterparts.12,13 When the risks of obesity and excess GWG are coupled, it leads to an escalating cycle of alarming risks for future generations.14

Low-income women are more likely to be affected by obesity than higher income women.15 Non-Hispanic blacks in the United States have the highest age-adjusted obesity rates in the nation.16 Overweight, non-Hispanic black women are at the highest risk for lifelong postpartum weight retention, so there is an urgent need for effective, socially and culturally appropriate interventions targeting these groups.17

Prenatal care provides a unique window of opportunity for obesity prevention and intervention.18 Unfortunately, information from physicians about GWG is often insufficient and inaccurate.19–21 In a prospective cohort study of low-income, urban women, strong predictors of excess GWG included both receiving clinician advice discordant with IOM guidelines and having a high BMI early on in pregnancy.22 The IOM’s 2009 report on weight gain during pregnancy outlined several recommendations for action, including routine reporting of GWG by racial/ethnic group and socioeconomic status. Data on GWG in diverse populations was identified as a major research gap that needs to be addressed.2 Despite this, little research has been done to identify facilitators and barriers to healthy nutrition and weight gain in diverse pregnant populations, especially low-income, minority overweight and obese women.

The findings of a qualitative study examining facilitators and barriers to healthy eating and healthy GWG among low-income, overweight and obese, pregnant and postpartum women, and obstetricians-gynecologists (OB-GYNs) from a community-based perinatal clinic in Madison, WI are described. This formative research is designed to inform culturally and socially appropriate interventions to increase healthy diet and lifestyle behaviors, prevent excess gestational weight gain, and reduce adverse perinatal and long-term health outcomes among women and children.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

English-speaking mothers (n=29) and OB-GYNs (n=9) were recruited from a community-based perinatal center in Madison, WI, which provides comprehensive low and high risk obstetrical services to predominantly low-income, minority women. Participating mothers were identified through chart review of pregnancy status. Inclusion criteria included: pregnant or 6 weeks to 1 year postpartum, prenatal intake body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25, 18 years or older, English speaking, and eligible for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), a federally funded nutrition program for participants whose gross income falls below 185% of the US poverty income guidelines. Women were categorized as first half of pregnancy (under 26 weeks gestation, n=12), second half of pregnancy (26 weeks gestation to term, n=10), or postpartum (6 weeks post-delivery to one year postpartum, n=7). Participating OB-GYNs were clinicians from the same clinic. Participants were recruited by one of the coauthors (AMS) who was an OB-GYN in the clinic prior to the commencement of the study.

Procedures

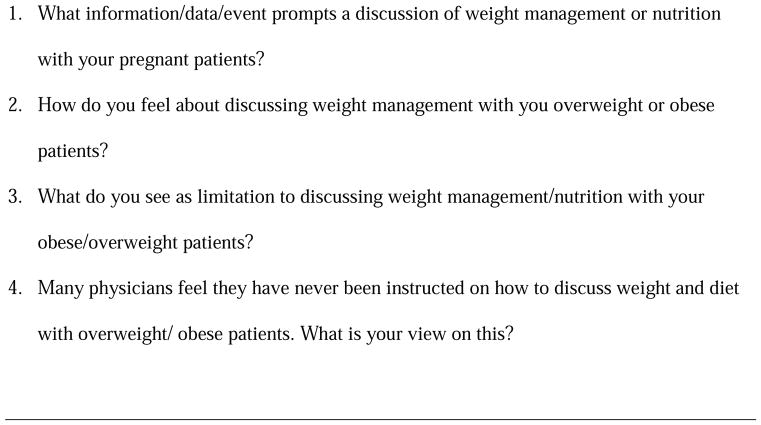

A study advisory committee, comprised of community members (women/mothers of similar background, race, and ethnicity to study participants), study investigators, OB/GYNs, and Wisconsin Department of Health officials, guided the development of focus group questions based on the Social Ecological Model (SEM).23 The SEM has been adopted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to address many public health problems, from domestic violence prevention to breast feeding promotion. This model employs a multi-level approach to prevention that addresses intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational/institutional, community, and societal/policy level influences on health behaviors.23 Thus, focus group questions were designed to elicit barriers and facilitators of healthy GWG across multiple levels of the SEM. The focus group questions are listed in Figure 1 (for women) and Figure 2 (for OB-GYNs).

Figure 1.

Focus Group Questions for Mothers

Figure 2.

Focus Group Questions for Physicians

Focus groups were facilitated by trained members from the advisory committee with similar race and ethnicity (Hispanic, black, or white) to the majority of focus group participants in each session. Facilitators were trained by an expert consultant.24–26 Ten focus group discussions (8 with community women, 2 with OB-GYNs), each lasting 90 minutes, were conducted at the cooperating obstetrics and gynecology clinic. Focus groups ranged in size from 3–5 people per group and were mostly mixed race and ethnicity with the exception of one all black group and one all non-Hispanic white group. The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent. OB-GYN participants received a gift card, and mother participants received either a new infant car seat or gift basket or gift card of equivalent value at study completion.

Data Analysis

Focus group audiotapes were transcribed verbatim and checked for errors. Researchers developed themes for an initial coding guide based on the interview guide and responses to focus group questions. A mixed methods approach to content analysis using both conventional (codes derived during analysis) and directed (initial coding scheme based on the SEM) content analysis was used.27 The coding guide was organized into six categories based on the SEM: 1) Intrapersonal, 2) Interpersonal, 3) Organizational/Institutional, 4) Community, 5) Policy/Society, and 6) OB-GYN. Transcripts were reviewed and coded by three researchers for common themes. A fourth researcher experienced in qualitative analyses reviewed code to ensure accurate coding. Investigators agreed that thematic saturation was reached, as no new themes were identified after completion of ten focus group sessions.

RESULTS

Table 1 outlines the characteristics of focus group participating mothers (n=29). The majority of women were either African American (n=14) or non-Hispanic white (n=12) and multiparous (n=20). All women qualified for WIC and were defined as low-income. Barriers and facilitators of healthy GWG were categorized according to the SEM. The OB-GYN participants (n=9) included mostly women (n=8) who were white (n=7), Native American (n=1), and mixed race (n=1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Focus Group Participants (n=29)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black | 14 (48) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 12 (41) |

| Hispanic | 3 (10) |

| Parity | |

| Primiparous | 9 (31) |

| Multiparous | 20 (69) |

| Pregnancy Status | |

| Under 26 weeks gestation | 12 (41) |

| 26 or more weeks gestation | 10 (34) |

| Postpartum (delivery to one year) | 7 (24) |

Intrapersonal

All women believed that intrapersonal factors either encouraged or discouraged GWG. Several themes emerged as intrapersonal barriers to healthy GWG, including: physiology (hunger, cravings, and aversions), financial factors, time constraints, and lack of knowledge or skills. Cravings and lack of knowledge or skills were the most commonly discussed. Facilitators that emerged for healthy GWG included: physiology (food aversions), adequate knowledge or skills, and past experience.

Barriers

For the majority of women, a prominent barrier to making healthy food choices during pregnancy was cravings for readily accessible, unhealthy foods, often in the context of consuming food to reduce stress or cope with depression. As one woman stated, “I think what makes it hard is you have cravings. Because no matter how much you try to eat the proper foods that you need to eat and the things that’s good for you, it’s that craving that you want, you want, you want.” Another woman mentioned, “You’re depressed so you’re not eating good. You know when you’re depressed you just don’t give a crap. You’re just like, ‘Whatever, it doesn’t matter anyway; I’m going to get fat anyway.’ … maybe some stress management and some counseling would have helped…to maybe eat better, because I think if you’re feeling better, you eat better.”

Most women discussed financial constraints as a barrier to healthy eating and preventing excess GWG, including insufficient income, the cost of healthy foods, and a fear of not being able to support a child. For example, “we get very limited assistance and we are taking anything we can get. I have become quite the little coupon clipper and watching the sales. We tend to go more for the carbohydrates because the stuff is less expensive” and “Eighty percent of the fear you get when you first find out you’re pregnant is how am I going to do this? How am I going to afford it?”

More than half of women described a lack of time to prepare healthy meals or engage in physical activity, as well as a lack of healthy cooking knowledge or skills. As stated by one woman, “(I eat) stuff that’s at a gas station or fast food, and it’s probably like, if I had more time or I was at home, I would cook or … grab something that was better.” Women’s personal beliefs and a lack of knowledge and skills also promoted weight gain, such as, “when you’re pregnant, you just think you can eat whatever you want.” A lack of knowledge and skills was discussed, such as “the most hard thing is cooking for me, like cooking it right and actually not using all the oil or the butter or adding cheese and everything to it. That’s my problem of eating right. It was the way I was always taught to just deep-fry everything.”

Facilitators

Women discussed food aversions (which led them to not want to eat), previous experiences or personal beliefs, and attitudes towards dietary choices as factors that prevented excess GWG. Additionally, personal motivation to achieve healthy pregnancy and newborn outcomes, described using terms such as “willpower” and “maternal instinct,” and a personal desire to lose weight postpartum were described as facilitators of healthy GWG. For example, “because I have to come back to my regular size when the baby comes out. That’s constantly on my mind, like don’t overdo it because you want your figure back … I’m constantly just dwelling on that.” Another woman stated, “I don’t eat right every time, but I try…because of the baby,…I don’t like eating vegetables, but I do it anyway.”

Previous pregnancy experience was another important factor in preventing excess GWG. Many mothers described trying to eat healthy so they did not gain as much weight as they had gained with their first pregnancy. As one women stated, “When I was with my first (child), I didn’t care. I know I ate anything anytime of the day, and I gained like 60 pounds. And with this one, I’ve been watching what I eat. I’ve been trying more fresh fruits and vegetables.”

Interpersonal

Women in this study reported receiving pregnancy-related nutritional advice from veteran mothers in their social networks, including their mothers, female neighbors, grandmothers, sisters, friends, cousins, and aunts. Healthcare and adjunct providers such as nurses, dietitians, social workers, and WIC staff were also named as important sources of information. Women nearly consistently indicated that their OB-GYNs provided some counseling about diet, nutrition, or GWG, though the extent and accuracy of such counseling could not be uniformly assessed. Women were more likely to trust and be persuaded by their OB-GYN’s advice or information provided by WIC than by advice from other sources, though many reported receiving minimal or conflicting information from different sources.

Barriers

Women discussed their children hindering them from buying healthy foods and asking for unhealthy foods when grocery shopping as barriers to consuming healthier foods. As one woman acknowledged, “my kids are always asking for things that aren’t healthy.” Additionally, interpersonal stressors at home and work were frequently identified as barriers. Sociocultural, family, and ethnic norms favoring overeating and high-fat, high-calorie food preparation were also identified as barriers to healthy eating. For example, “it’s the only time you get the special permission to be able to eat like a horse, and nobody looks at you funny, nobody says nothing to you about it.” Similarly, “it would have made it easier to eat healthier if I had good values instilled as a child.”

Facilitators

Many women discussed that having other children in the household was a facilitator to healthy eating and being active: “having a one year old, I want him to be healthy too, and he loves fruit and vegetables. So when I was pregnant, we ate together the same healthy stuff,” and “before all I did was just sit and watch TV and eat all the time. And now, with my kids being older and soccer practice, I’m doing this, doing that, and it just helps me move around.”

Women were most likely to listen to their primary care giver for advice on healthy eating and GWG. For example, “my doctor, she was really, really helpful. It was nice that she was a woman because she understands. She would… try to give me better ways of eating or exercising.” Being weighed and keeping track of weight gain (i.e. accountability to others) was a motivator for healthy GWG: “going to my checkups and getting weighed. That helped me.”

Organizational/Institutional

The majority of women found that information obtained from WIC, the perinatal clinic, churches, and the YMCA, were conflicting regarding healthy eating. Many women perceived the advice from organizations to be helpful; others did not change their behavior based on the advice or did not trust the advice. For example, “WIC pamphlets usually go in the garbage.” As opposed to, “my doctor and WIC, they told me soda is bad for me, and I’d catch diabetes, so I stopped drinking soda. They told me to water my juice down, so I do a lot of what they tell me.” However, many women mentioned that they received different information from their OB-GYN versus WIC, “sometimes they [WIC] have their views on things are much different than your doctor’s views.” When they received no advice about healthy GWG from their OB-GYN, they assumed that it was not that important and were left to come up with their own ideas about healthy GWG.

Community

Women perceived many community-level barriers to healthy GWG. Despite prompting, there was no discussion regarding community facilitators to healthy GWG.

Barriers

Transportation was a barrier for grocery shopping; women lived too far to walk to grocery stores: “you have to pay someone $10 or $15 to take you to the grocery store or a cab, and that’s expensive.” Often, convenience stores or pharmacies were identified as the only places where women could access food, which was noted as more expensive: “you blow your food stamps running back and forth to gas stations.”

The convenience of fast food restaurants also made healthy eating difficult. One woman stated, “well, you’re huge, pregnant, can barely get around, and you’ve got to stand up there and cook up something good, when it’s just as easy to go through the drive-through at Burger King, and get that same, filling effect, but not so nutritional.” Similarly, “It’s just food on the go,…you have kids at home that are always ‘McDonald’s, McDonald’s’. And it’s hard to eat when you have so much influence of bad foods around you. But when I lived in the country, it wasn’t so…in the city you’ve got…fast food (at) every corner.”

Policy/Society

At the policy/society level, complexity of policies and social stigma were barriers, while media was perceived as a potential facilitator.

Barriers

Complexity of WIC policies was a barrier because of rules and restrictions on allowed food. For example, “hoops, jumping through hoops (referring to all the rules).” Social stigma was also identified as a barrier. Some women felt frustrated and embarrassed with WIC vouchers, for example, “the whole process…has always been very (pause), I mean my blood pressure will go up. My face will get hot…because you get in line and then you, and because of all the new changes, grocery stores haven’t caught up with it yet. So then you stand there, literally sometimes for…”

Facilitators

The availability of health information via multiple media sources, such as books, internet, and TV, was an important facilitator to engaging in healthy behaviors. For example, “…starting with the book they give you at your first visit…using that as a reference book throughout my pregnancy and afterwards. I kept going back.” Additionally, the WIC policies for buying healthy foods enabled many women to eat healthier than they otherwise would have.

Interventions to encourage healthy gestational weight gain

Community participants discussed how best to support healthy eating and healthy GWG. Women suggested having peer-facilitated group classes that involved exercise and cooking, sharing personal stories and experiences, and including guest experts to provide information in a non-threatening and fun way. Women discussed information that should be part of group classes, including: how the baby grows, nutrition, labor and delivery, money management, single parenting, and wellbeing after delivery. Most women felt that “getting each other’s self-experiences helps a lot,” and “a group class (would be helpful), because you learn from others and people learn from you.” While the group support approach was generally supported, there was hesitation expressed by some women who indicated they would feel uncomfortable sharing personal details in a group environment. The women felt that having one-on-one sessions, in addition to the group sessions, would be helpful. Most women identified that having the opportunity to discuss their challenges and successes during the focus groups for this research study was really helpful. For example, “we can sit and discuss what we need to discuss and get the help that we need, and feel good about yourself when you leave.” The women felt that having a comfortable setting with a group of women led by an experienced mother (peer) would be ideal. Additionally, it would have to be at a day/time that was convenient with child care provided. Lastly, women discussed a desire for stress management and emotional support during the group sessions which would help women to engage in healthier behaviors.

Obstetrician-Gynecologists

Most OB-GYNs felt uncomfortable counseling patients about GWG during pregnancy. One primary reason was because they didn’t feel adequately trained to do so: “We have no training in this…I can speak generally about high fiber, low fat diets and trying to avoid, you know, processed carbohydrates…after that, like I stop.” Another physician noted, “in med school, we got extensive training in smoking cessation…How to interview them, how to talk to them, and the different stages they go through, who’s ready, who’s not…but nothing on obesity.” Additionally, OB-GYNs explained they did not have time or felt other more pressing issues had to take priority. Specifically, one OB-GYN stated, “… you’re talking about…you’re a smoker and you’re overweight, and you’re on methadone… There’s a long list…you’re triaging to more survival like issues.” Another OB-GYN put it this way, “it’s hard to get them to focus on living healthy, when they’re just trying to live.” OB-GYNs also indicated that they hesitated to make recommendations about healthy eating and physical activity because they (the OB-GYNs) perceived barriers for their patients in achieving these behaviors. One OB-GYN said, “I can talk about this until I’m blue in the face…and as much as they want to…do this with me, there’s just no feasible way they can do that and still feed their family or themselves,” and another OB-GYN said, “something that keeps me from…talking to them about (exercising is) because they can’t afford to go to a gym.” Most OB-GYNs did feel comfortable referring patients to dietitians, but they did not know what the dietitian told the patients, and therefore could not reinforce what the dietitian had said when they next saw the patient. As one OB-GYN put it, “we need to have communication between nutritionists and the physician team.”

DISCUSSION

This qualitative investigation identified multi-level factors that affect healthy eating and GWG among low-income overweight and obese women. Additionally, OB-GYNs discussed challenges and opportunities for counseling about GWG. Findings suggest that there are public health opportunities to promote healthy GWG and that a multi-level approach is warranted.

Our findings identified several barriers to healthy GWG that have also been suggested by previous research, including the powerful effect of family members and cultural and social norms promoting the desirability of large babies and the need to “eat for two,” 28 the challenge of coping with food cravings during pregnancy,29,30 and poor food environments, including ubiquitous fast food and unhealthy foods, and lack of transportation.29 Our findings also corroborate previous reports that a desire to return to a thinner pre-pregnancy weight is a strong motivating factor and may reduce risk for excess GWG,31,32 that women are motivated to eat healthy for the sake of their babies,32 and that personal experience with excess GWG and postpartum weight retention during a prior pregnancy is a salient motivator of healthy GWG. 28

Findings also identified areas of opportunity for intervention. Lack of knowledge and skills surrounding healthy nutrition and food preparation was a commonly cited barrier to healthy GWG. Pregnancy information from media was a facilitator to healthy GWG. This suggests opportunities to use various media modalities to reach women with information to assist healthy eating and healthy GWG. On the other hand, women’s reliance on multiple sources of health information underscores the challenge of ensuring that women are using high-quality information from credible sources.

Consistent with previous studies,19,32 we found that many women receive inadequate or conflicting information about pregnancy nutrition and GWG from health care providers. Most women reported that they trusted their OB-GYN’s advice the most. However, in the absence of advice about healthy GWG from their OB-GYN, many women assumed that it was not that important and were left to come up with their own ideas about healthy GWG. Likewise, when receiving conflicting advice from their OB-GYN, WIC nutritionist, mother, best friend, and the internet, women struggled to figure out which approach made sense for them. Due to this conflicting advice combined with prevalent myths and misconceptions (e.g. “eating for two”), cultural and social norms, and individual variability between women and within a woman across different pregnancies, many women described a trial and error approach to healthy eating and GWG. This points to a need for coordination across multiple sectors, so that advice is consistent and a universal part of prenatal care. It also points to a need for broader education to shape cultural norms and media messages surrounding healthy eating and GWG in pregnancy.

OB-GYNs discussed a lack of time and training to counsel patients on weight control during a typical office visit. Thus, referring patients to a weight control specialist is advisable, but better communication between the specialist and the OB-GYN would most likely strengthen the impact of that intervention. This is especially true given that most of the women in the focus groups gave the most credence to advice from OB-GYNs. Indeed, it was noted that if an OB-GYN did not mention nutrition or physical activity, appropriate GWG, or follow-up on a referral to a weight-control specialist, patients did not perceive it as important. Our findings are corroborated by previous research suggesting that information from health care providers about GWG is often inaccurate and insufficient.19–21 Thus, interventions that target physicians are important to decrease excessive GWG among low-income overweight and obese women.

The current study was novel in its attempt to solicit women’s suggestions about how to help women like themselves achieve healthy GWG. There was consensus that ideal intervention approaches would include peer-facilitated support groups with information from experts in pregnancy on a variety of topics, e.g. food preparation, nutrition, exercise, stress management, social support, and finances. While peer-led support groups were generally agreed upon as an ideal approach, a small number of focus group participants indicated discomfort with the idea of sharing personal information with others. Therefore, the group approach may best be used as an option, with traditional one-on-one care still offered for those women who prefer it. The desired approach is reminiscent of group prenatal care models such as CenteringPregnancy33–35 which has been shown to decrease excessive gestational weight gain.36 Future research should continue to examine whether this model of care is associated with healthy GWG. Additionally, given that WIC was noted by participants as being influential, and facilitated group discussions have been successfully implemented in WIC programs 37, this efficient, low-cost approach should be considered. Facilitating this approach in a manner that includes two-way communication with OBY-GYNs is likely to have greater impact.

One strength of the current study is the in-depth nature of information provided by participants, including responses that spanned all levels of the SEM. We were therefore able to identify lesser-known and infrequently examined barriers and facilitators to healthy eating and GWG, such as food cravings and aversions, mental health, relationships, family/work stressors, community organizations such as WIC, and health clinics. Another strength is that participants made concrete recommendations for future programs that they would deem desirable and feasible within the constraints of their lives and communities. Collaboration with community members, obstetricians, and Department of Health Officials to develop focus group questions, conduct focus groups, and analyze results ensured that our findings would be useful to current and future stakeholders.

The current study included some limitations. Because there was a relatively small number of low-income, overweight and obese women included (n=29) who were recruited through one perinatal clinic serving a low-income, high risk population in Madison, WI, results may have limited generalizability. However, within this context, community participants did represent a mix of race and ethnicity, as well as women from rural and urban locations. The use of mixed race groups may have been a weakness of the study design if focus group participants would have felt more comfortable sharing personal information if they perceived other women in the group to be more like them. However, observers noticed that characteristics other than race and ethnicity seemed to influence amount of sharing (e.g. similar life experiences related to relationships and children seemed to encourage sharing between women of different races and ethnicities). Follow-up questions, themes, and conclusions were derived through an interactive process with participants so there was some variation in information available between groups. In reviewing transcribed audiotapes and categorizing responses by level of the SEM, results may be limited by the inferential and iterative nature of the data review process.

In conclusion, this study suggests that public health opportunities to promote healthy GWG are possible via multi-level approaches. Women identified an intervention approach using peer-led support groups with appropriate expert input to combat excess GWG. OB-GYNs are encouraged to partner with nutrition specialists, using two-way communication to enhance follow-up with patients.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Health practitioners should consider a peer-led, group-care model involving input from professionals in the areas of physical activity, nutrition, personal finance, child development, and stress management for low-income pregnant women who are overweight or obese. This model could include a CenteringPregnancy approach or facilitated group discussions which have both been shown to be efficacious. Additional research should investigate the efficacy of such care compared to more traditional models. Health care providers could improve care within existing models by implementing improved referral systems that include follow-up communication between providers and back to the patient.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The work also was supported, in part, by awards T32HD049302 and K12HD055894 from the Eunice Kennedy Schriver National Institute of Child Health And Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Funding for this project was also provided by the UW School of Medicine and Public Health from the Wisconsin Partnership Program. The authors would like to thank the women and physicians who participated in focus groups and made this work possible. We would also like to thank our research assistants: Shari Barlow, Abby Panozzo, Kristin Prewitt.

Footnotes

Work Conducted At: University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Madison, WI

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Cynthie K. Anderson, Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Madison, WI.

Tanis J. Walch, Assistant Professor, University of North Dakota, Department of Kinesiology & Public Health Education, Grand Forks, ND.

Sara M. Lindberg, Assistant Scientist, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Center for Women’s Health and Health Disparities Research, Madison, WI.

Aubrey M. Smith, Prevea Health, Sheboygan, WI.

Steven R. Lindheim, Professor, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Director, Reproductive Endocrine Infertility, Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio.

Leah D. Whigham, Executive Director, Paso del Norte Institute for Healthy Living, El Paso, TX.

References

- 1.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Bish CL, D’Angelo D. Gestational weight gain by body mass index among US women delivering live births, 2004–2005: fueling future obesity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:271, e 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington D.C: National Academy Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hochner H, Friedlander Y, Calderon-Margalit R, Meiner V, Sagy Y, Avgil-Tsadok M, Burger A, Savitsky B, Siscovick DS, Manor O. Associations of maternal prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with adult offspring cardiometabolic risk factors: the Jerusalem Perinatal Family Follow-up Study. Circulation. 2012;125:1381–1389. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.070060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drake AJ, Reynolds RM. Impact of maternal obesity on offspring obesity and cardiometabolic disease risk. Reproduction. 2010;140:387–398. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommer C, Mørkrid K, Jenum AK, Sletner L, Mosdøl A, Birkeland KI. Weight gain, total fat gain and regional fat gain during pregnancy and the association with gestational diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Int J Obes. 2014;38:76–81. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McClure CK, Catov JM, Ness R, Bodnar LM. Associations between gestational weight gain and BMI, abdominal adiposity, and traditional measures of cardiometabolic risk in mothers 8 y postpartum. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:1218–25. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.055772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rong K, Yu K, Han X, Szeto IM, Qin X, Wang J, Ning Y, Wang P, Ma D. Pre-pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2014 Nov 20;:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014002523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hedderson MM, Weiss NS, Sacks DA, et al. Pregnancy weight gain and risk of neonatal complications: macrosomia, hypoglycemia, and hyperbilirubinemia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;108:1153–1161. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000242568.75785.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stotland NE, Cheng YW, Hopkins LM, Caughey AB. Gestational weight gain and adverse neonatal outcome among term infants. Obstet & Gynecol. 2006;108:635–643. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000228960.16678.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tie HT, Xia YY, Zeng YS, Zhang Y, Dai CL, Guo JJ, Zhao Y. Risk of childhood overweight or obesity associated with excessive weight gain during pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;289:247–57. doi: 10.1007/s00404-013-3053-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaillard R, Steegers EA, Franco OH, Hofman A, Jaddoe VW. Maternal weight gain in different periods of pregnancy and childhood cardio-metabolic outcomes. The Generation R Study. Int J Obes. 2014 Oct 7; doi: 10.1038/ijo.2014.175. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muktabhant B, Lumbiganon P, Ngamjarus C, Dowswell T. Interventions for preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD007145:1–121. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007145.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists. Obesity in pregnancy. ACOG Committee Opinion No.549. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;121:213–217. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000425667.10377.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cnattingius S, Villamor E, Lagerros YT, Wikström AK, Granath F. High birth weight and obesity-a vicious circle across generations. Int J Obes. 2012;36:1320–1324. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogden CL, Lamb MM, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Obesity and socioeconomic status in adults: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS data brief no 50. Hyattsville, MD: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrams B, Heggeseth B, Rehkopf D, Davis E. Parity and body mass index in US women: A prospective 25-year study. Obesity. 2013;21:1514–1518. doi: 10.1002/oby.20503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelan S. Pregnancy: a “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:135.e131–135.e138. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stengel MR, Kraschnewski JL, Hwang SW, Kjerulff KH, Chuang CH. “What my doctor didn’t tell me”: examining health care provider advice to overweight and obese pregnant women on gestational weight gain and physical activity. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22:e535–e540. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phelan S, Phipps MG, Abrams B, Darroch F, Schaffner A, Wing RR. Practitioner advice and gestational weight gain. J Womens Health. 2011;20:585–91. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stotland NE, Haas JS, Brawarsky P, Jackson RA, Fuentes-Afflick E, Escobar GJ. Body mass index, provider advice, and target gestational weight gain. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:633–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000152349.84025.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herring SJ, Nelson DB, Davey A, et al. Determinants of excessive gestational weight gain in urban, low-income women. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22:439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krueger RA. Developing questions for focus groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krueger RA, King JA. Involving community members in focus groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herring S, Henry T, Klotz A, Foster G, Whitaker R. Perceptions of Low-Income African-American Mothers About Excessive Gestational Weight Gain. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1837–1843. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0930-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodrich K, Cregger M, Wilcox S, Liu J. A Qualitative Study of Factors Affecting Pregnancy Weight Gain in African American Women. Matern Child Health J. 2013 Apr 01;17:432–440. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1011-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orloff NC, Hormes JM. Pickles and ice cream! Food cravings in pregnancy: hypotheses, preliminary evidence, and directions for future research. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1076. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehta U, Siega-Riz A, Herring A. Effect of Body Image on Pregnancy Weight Gain. Matern Child Health J. 2011 Apr 01;15:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0578-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiles R. The views of women of above average weight about appropriate weight gain in pregnancy. Midwifery. 1998 Dec;14:254–260. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(98)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shakespear K, Waite PJ, Gast J. A comparison of health behaviors of women in centering pregnancy and traditional prenatal care. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14:202–208. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reid J. Centering Pregnancy®: A Model for Group Prenatal Care. Nurs Womens Health. 2007;11:382–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-486X.2007.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lathrop B. A Systematic Review Comparing Group Prenatal Care to Traditional Prenatal Care. Nurs Womens Health. 2013;17:118–130. doi: 10.1111/1751-486X.12020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanner-Smith EE, Steinka-Fry KT, Gesell SB. Comparative effectiveness of group and individual prenatal care on gestational weight gain. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:1711–20. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1413-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abusabha R, Peacock J, Achterberg C. How to make nutrition education more meaningful through facilitated group discussions. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:72–76. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00019-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]