Abstract

Less than 10% of corneal allografts undergo rejection even though HLA matching is not performed. However, second corneal transplants experience a three-fold increase in rejection, which is not due to prior sensitization to histocompatibility antigens shared by the first and second transplants since corneal grafts are selected at random without histocompatibility matching. Using a mouse model of penetrating keratoplasty we found that 50% of the initial corneal transplants survived, yet 100% of the subsequent corneal allografts (unrelated to the first graft) placed in the opposite eye underwent rejection. The severing of corneal nerves that occurs during surgery induced substance P (SP) secretion in both eyes, which disabled T regulatory cells that are required for allograft survival. Administration of an SP antagonist restored immune privilege and promoted graft survival. Thus, corneal surgery produces a sympathetic response that permanently abolishes immune privilege of subsequent corneal allografts, even those placed in the opposite eye and expressing a completely different array of foreign histocompatibility antigens from the first corneal graft.

Keywords: Cornea, Immune Privilege, Keratoplasty, Nerves, T regs

Introduction

The cornea is the most frequently transplanted tissue in humans and enjoys a success rate that exceeds all other forms of solid organ transplantation (1, 2). Over 40,000 corneal transplants are performed each year in the United States, but less than 10% will undergo rejection, even though HLA matching is not routinely performed and topical corticosteroids are the only immunosuppressive agents used (3). However, rejection rises three-fold in hosts receiving second corneal transplants(4). This escalated rejection is probably not the result of prior sensitization to histocompatibility antigens shared by the first and second transplants since corneal grafts are routinely selected at random without histocompatibility matching. Instead, rejection of second corneal allografts is due to the loss of ocular immune privilege.

The cornea is endowed with multiple anatomical, physiological, and immunoregulatory properties that contribute to its immune privilege and the high success rate of corneal transplants (1, 5, 6). Corneal transplants are grafted into graft beds that lack both blood and lymph vessels, thereby blocking the afferent arm of the immune response (7–9). The cornea is also decorated with cell membrane molecules, including FasL and PD-L1, which induce apoptosis of infiltrating lymphocytes and block the efferent arm of the immune response(10–13). A growing body of evidence indicates that the immune privilege of orthotopic corneal allografts is intimately associated with their ability to induce CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+T regulatory cells (Tregs)(14–16)that suppresses the alloimmune response through a process that requires glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor family-related protein (GITR)(15–17), TGF-β1 (16), and CTLA-4(16). The close correlation between corneal allograft rejection and the absence of Tregs prompted us to test the hypothesis that the heightened incidence of corneal allograft rejection in patients receiving a second corneal transplant is due to a perturbation in Treg function.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult female BALB/c (H-2d) and C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). A/J (H-2a), C3H/HEJ (H-2k) and SP−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the UT Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Animals cared for in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision.

Corneal Transplantation

Full thickness C57BL/6, C3H, A/J, or BALB/c corneas were transplanted onto the eyes of BALB/c mice as previously described. Corneal grafts were examined 2–3 times a week for opacity, neovascularization and edema. Graft opacity was scored using a scale of 0–4 as previously described (18). Median survival times (MST) were used to determine statistical significance between groups.

Intrastromal Suturing and Corneal Surface Trephining

A 2.0 mm circular trephine was used to incise the cornea by applying slight pressure while twisting four to five times over the corneal surface, through the epithelial layer and the upper two-thirds of the stromal layer. A vascularized graft bed was produced placing three interrupted sutures (11-0 nylon, 50-μm diameter needle; Sharpoint, Vanguard, Houston, TX) through the central cornea 2 weeks prior to corneal transplantation (19).

Corneal Nerve Imaging

Trephined eyes of BALB/c mice were assessed for the presence and integrity of corneal nerves. Enucleated eyes from mice were treated with Dispase II for 2 hours at room temperature then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, permeablized and blocked in 1% BSA in PBS and 0.2% Triton X-100 for 2 hours at room temperature. Corneas were incubated with rabbit anti-mouse β III tubulin primary antibody (TUJ1) IgG (Covance, Richmond, CA), washed in PBS, corneas, and incubated with Propidium Iodide and secondary antibody (Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG, Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA) for 2.5 hours at room temperature.

Spantide II Treatment

72 μg of Spantide II (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was given intraperitoneally either the day before the left eye was trephined, or the day before the right eye received a C57BL/6 corneal allograft. Treatment was administered once daily, until termination of the experiment.

Quantitative Real time PCR (q-RT-PCR)

The anterior tissue, cornea and iris, of the trephined or unmanipulated contralateral eye from 3 donors were excised and placed on ice in 700 μl cRPMI. The tissue was homogenized and total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNEasy Isolation Kit. Real-time PCR was performed using the RT2 First Strand and RT2 SYBR Green kits with pre-formulated primers for Tac1, Pomc, VIP, Calca, Sst, and GAPDH (SA Biosciences, Frederick, MD). The results were analyzed by the comparative threshold cycle method and normalized with GAPDH as an internal control.

Neuropeptide Protein quantification by Enyzme Immunoassay

The anterior tissue (cornea and iris) of the trephined and unmanipulated eyes from 4 donors were excised, sonicated, and the lysates were centrifuged. Supernatants evaluated by EIA for Substance P (SP; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), α-MSH, VIP, Somatostatin, and CGRP (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals) (20).

Substance P Injection

A single intravenous (i.v.) or subconjunctival injection of SP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered to BALB/c mice prior to their receiving C57BL/6 corneal allografts.

Local Adoptive Transfer Assay

The LAT assay to test the suppression of CD4+CD25+ Tregs was performed(21). CD4+CD25+ putative T regulatory cells (Tregs) were incubated with BALB/c APC pulsed with cornea donor’s splenocytes and responder CD4+ T cells from corneal allograft rejectors in a 1:1:1 ratio. Left and right ear pinnae of naïve BALB/c mice were injected with 20 μl (1 × 106) of the mixed-cell population. The opposite ear was injected with HBSS as a negative control. Ear swelling was measured 24 hr later to measure DTH.

Flow Cytometry

CD4+CD25+ T regs were isolated from the spleens of BALB/c mice 21 days post transplantation using T reg isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) and were labeled with CFSE (16). CD4+ T cells from naïve BALB/c mice were co-cultured for 72 hr with CD4+CD25+ T regs in the presence of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA)(16). CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25+ T regs were isolated by flow cytometry and interrogated for expression of Foxp3, CTLA-4, GITR, and TGFβ1 using the following monoclonal antibodies: APC conjugated rat anti–mouse CD25 (BD Biosciences), APC conjugated hamster anti-mouse CTLA-4 (eBioscience), APC conjugated rat anti-mouse GITR (eBioscience), APC conjugated rat anti-mouse Foxp3 (eBioscience), APC conjugated streptavidin (eBioscience), and biotinylated anti-TGF-β1 antibody (R&D systems). Flow cytometric analyses were performed on a FACSCalibur with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis

The log-rank test was used analyze the differences in the tempo of corneal graft rejection using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Comparisons yielding p < 0.05 were considered significantly different. Student’s t-test was used to analyze results from LAT assays.

Results

Penetrating keratoplasty in one eye abolishes immune privilege in the opposite eye

We tested the hypothesis that a first corneal allograft abolishes immune privilege of subsequent grafts from unrelated donors. C3H/Hej (H-2k) or A/J (H-2a) corneal allografts or BALB/c syngeneic corneal grafts were grafted orthotopically to the right eyes of BALB/c (H-2d) mice. Sixty day later allografts were removed and replaced with C57BL/6 corneal allografts. All C57BL/6 grafts placed into previously grafted eyes underwent rejection (MST = 7)(Figure 1A). Moreover, 100% of C57BL/6 grafts transplanted into eyes that previously had healthy BALB/c syngeneic grafts underwent rejection (MST=15.5)(Figure 1B). By contrast, only 50% of C57BL/6 corneal allografts underwent rejection in hosts that had not received previous corneal grafts. This abolition of immune privilege also occurred in the contralateral eye. That is, mice that received corneal allografts in the right eye rejected 90–100% of allografts transplanted into the left eye (MST = 12.5 and 16 respectively)(Figure 1C and 1D). Importantly, BALB/c syngrafts never underwent rejection, even in eyes that had previously rejected a corneal allograft (Figure 1B). Thus, hosts that previously received a corneal transplant had a heightened incidence of rejection of C57BL/6 allografts compared to mice that received C57BL/6 allografts as the primary transplant. These results demonstrate that the transplantation procedure itself robs the contralateral eye of its immune privilege and provokes rejection of subsequent corneal allografts. We have termed this condition in which a perturbation of the ocular surface in one eye alters immune privilege in the opposite eye, sympathetic loss of immune privilege (SLIP).

Figure 1. Corneal transplantation in one eye abolishes immune privilege in the opposite eye.

A) C3H/Hej (H-2k) or A/J (H-2a) corneal allografts were transplanted to the right eyes of BALB/c (H-2d) mice. Sixty days later the rejected grafts were removed and replaced with C57BL/6 (H-2b) corneal allografts. C57BL/6 corneal allografts in previous recipients of C3H/Hej corneal allografts (median survival time, MST= 7; N= 18) or A/J corneal allografts (MST =16; N= 8). C57BL/6 corneal allografts rejection in naïve BALB/c hosts (MST = 46; P < 0.001; N= 10) B) C57BL/6 corneal allografts were rejected in 100% of the hosts that had been previously grafted with a syngeneic BALB/c cornea graft (MST = 15.5; N= 15). Rejection of C57BL/6 corneal allografts in naïve hosts (MST = 46; P< 0.001; N=10). BALB/c syngeneic corneal grafts were not rejected by hosts that had been previously grafted with syngeneic BALB/c grafts (N= 12). C) C57BL/6 corneal allografts underwent rejection in hosts grafted in the right eyes with either C3H/HeJ (MST = 12.5; N= 12) or A/J (MST = 16; N=7) corneal allografts (P <0.001). D) Syngeneic BALB/c corneal grafts into right eyes first; BALB/c grafts or C57BL/6 corneal allografts grafted to the left eyes 60 days later. 90% of the C57BL/6 corneal allografts were rejected (MST = 20; N=8), which was significantly swifter than the rejection of C57BL/6 corneal allografts in naïve hosts (MST = 46; N= 10; P< 0.032). None of the syngeneic BALB/c corneal grafts underwent rejection (N= 9). All experiments were performed at least twice with similar results.

Circular corneal incision in one eye robs the other eye of its immune privilege

Orthotopic corneal transplantation involves preparing the graft bed using circular incisions and suturing the graft into place. We examined the effect of each of these procedures on immune privilege in the opposite eye. BALB/c mice were treated by: a) placing three sutures in the cornea; b) placing an “X” shaped incision in the cornea; or c) making a circular incision in the cornea. Fourteen days later, C57BL/6 corneal allografts were placed into the manipulated eye or the opposite eye. As previously shown (8), corneas treated with sutures became heavily vascularized and 100% of corneal allografts placed into these eyes underwent rejection (MST = 18) (Figure 2A). By contrast, sutures did not affect rejection of corneal allografts transplanted onto the opposite eye, which displayed the same acceptance rate as naïve mice (MST = 34 and MST =33; P.0.05) (Figure 2A; P>0.05). Likewise, an “X” incision in one eye did not affect the fate of corneal allografts placed into the opposite eye. Only 60% of the grafts underwent rejection, which was the same as naïve hosts (Figure 2B). By contrast, shallow circular corneal incisions (i.e., trephining) placed in one eye abolished immune privilege in the opposite eye and resulted in 100% graft rejection (MST = 18) (Figure 2C). Surgery-induced abolition of immune privilege was immediate and long-lived, as mice subjected to trephining in one eye and transplanted with corneal allografts in the opposite eye 100 days later rejected 90% of their allografts (MST = 22) (Figure 2D). Trephining also abolished an existing state of immune privilege. That is, trephining the left eyes of mice that had long-standing corneal allografts in the right eye, resulted in 100% rejection of the previously clear grafts (Figure 2E–2G).

Figure 2. Circular corneal incision in one eye robs the other eye of its immune privilege.

A) Sutures were inserted into the corneas in right eyes of BALB/c mice before applying C57BL/6 corneal allografts into either eye. 100% of the corneal allograft rejection in pre-sutured eyes (MST =18; N=10); 60% rejection in opposite eye of sutures (MST = 34; N=10), P<0.001. Corneal allograft rejection in naïve BALB/c mice= 50%; MST = 33; N= 10; P>0.05. B) “X” shaped incision in left eye prior to applying C57LBL/6 corneal allografts into the right eye. Rejection in “X” shaped corneal incision group: MST = 36; N= 10. Naïve group: MST = 34; N=10; P>0.05). C) 360° corneal incisions 14 days prior to grafting. Corneal allografts opposite eye of the 360° corneal incision: MST = 18; N= 19; corneal allografts placed into the same eye as 360° corneal incisions: MST =25; N=18; P<0.03; D) 360° corneal incisions in left eyes 60 days (MST = 22; N= 9) and 100 days (MST = 22; N = 10) prior to application of C57BL/6 corneal allografts in the right eyes. P>0.05. Naive controls: MST = 34; N = 10 and MST = 34.5; P<0.05 compared to both corneal incisions groups. E) 360° corneal incisions were made in the left eyes of BALB/c mice with clear C57BL/6 corneal allografts that had been in place in the right eyes for 30 days; F) clear C57BL/6 corneal allograft on right eye of a BALB/c mouse 30 days after transplantation and one day before trephining the left eye. G) Same graft shown in Figure F, but 22 days after making circular incisions in the opposite eye. All experiments were performed at least twice with similar results.

Circular corneal incisions induce substance P expression in the opposite eye, which abolishes immune privilege of subsequent corneal allografts

The cornea is the most densely innervated tissue in the body with approximately 300 times as many sensory nerves as the skin (22). Accordingly, we examined the integrity of corneal nerves following the placement of either circular incisions or “X” shaped incisions. Although normal corneas contained a dense network of nerves (Figures 3A and 3D), circular incisions produced a swift dissipation of corneal nerves (Figures 3B and 3E). By contrast, “X” shaped incisions produced a modest diminution of corneal nerves that was significantly less severe than that produced by circular incisions (Figures 3C and 3F).

Figure 3. Effect of circular corneal incisions on corneal nerves.

A) Cornea from a normal BALB/c mouse; B) cornea collected from a BALB/c mouse 96 hr after being scored with shallow360° incisions created by a 2.0 mm trephine. Arrows indicate site of circular corneal incision. C) Cornea collected 96 hr after being scored with an “X” shaped incision. Corneal nerves were stained with rabbit anti-mouse β tubulin III primary antibody (TUJ1) IgG (Covance, Richmond, CA) and were viewed by confocal microscopy. “C” indicates center of cornea. D) normal cornea. E) Cornea with circular incision (stained with India ink). F) Cornea with “X-shaped” incision (stained with Evan’s blue).

Four neuropeptides have been implicated in either the maintenance or the abrogation of immune privilege in the anterior chamber (AC) of the eye: a) substance P (SP); b) α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH); c) vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP); and d) calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)(5). α-MSH, VIP, and CGRP are known to suppress delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) and contribute to immune privilege in the AC of the eye (23–25). By contrast, SP abrogates immune privilege in the AC (26). We examined the effect of circular corneal incisions on neuropeptide release in the operated eye and the contralateral un-manipulated eye. Circular incisions induced a steep upregulation of SP, CGRP, and VIP and a down regulation of α-MSH in the opposite eye (Figures 4A–4D). This resulted in a >270% increase in SP levels in both the trephined eye (not shown) and the contralateral un-manipulated eye (Figure 4A). The surgery-induced abrogation of immune privilege could be recapitulated with a single subconjunctival injection of one picogram of SP in either eye (MST =19) (Figure 4E). Moreover, a single i.v. injection of one pg of SP abolished immune privilege for 100 days resulting in 100% graft rejection (MST = 19.5) (Figure 4F). Intravenous injection of as little as 0.1 pg of SP ablated immune privilege and led to 90% graft rejection (Figure 4G). Administration of the SP receptor antagonist, Spantide II, to mice subjected to trephining restored immune privilege and resulted in 60% graft acceptance compared to 90% rejection that occurred in trephined mice that were not treated with Spantide II (Figure 4H). Although α-MSH is closely associated with immune privilege in the anterior chamber and was elevated in mice subjected to circular corneal incisions, neither subconjunctival nor i.p. injection of α-MSH enhanced corneal allograft survival in either trephined hosts or naïve hosts (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Circular corneal incisions induce SP expression in the opposite eye, which abolishes immune privilege of corneal allografts in both eyes.

360° incisions were made in the right eyes of BALB/c mice and EIAs were used to quantify: A) SP, B) α-MSH, C) VIP, and D) CGRP expression in the anterior tissue of the left eye. Horizontal line represents baseline expression of each neuropeptide in eyes of normal mice. E) SP (1.0 pg) was injected subconjunctivally into right eyes of BALB/c mice one day before placing a C57BL/6 corneal allograft onto either the right or left eye (N= 15; MST = 19.5; P = 0.02 and N = 8 ; MST = 17; P = 0.02, respectively) in each group); F) SP (1.0 pg) was injected i.v. into BALB/c mice either 1 or 100 days prior to their receiving C57BL/6 corneal allografts (N= 15; MST = 18.5 and N = 9; MST = 28, respectively); SP groups vs untreated (N = 10; MST = 34) P = 0.04. G) SP (0.1 or 1.0 pg) was injected i.v. into BALB/c mice one day prior to the application of C57BL/6 corneal allografts. N = 10 for 0.1 pg group; N= 9 for 0.01 pg group. P= 0.001. H) 360° corneal incisions (trephine) were made in the left eyes of BALB/c mice. Sixty days later mice Spantide II (72 μg/day; i.p. N = 8 MST = 23) treatment was initiated and mice were grafted with C57BL/6 corneal allografts 24 hr after Spantide treatment was initiated. Mice received Spantide II for 60 consecutive days. Spantide II group vs. other two groups. (60 day trephine N = 10; MST = 19; P = 0.017 .Naïve recipients N = 10; MST = 34 P > 0.05). All experiments were performed at least twice with similar results.

Figure 5.

Effect of exogenous α-MSH on corneal allograft survival. A) 360° incisions (trephine) were made in the right eyes of BALB/c mice on day 0 and α-MSH (2 μg; i.p.) was injected on days -1 and every 3 days thereafter for 15 days. C57BL/6 corneal allografts were transplanted to the left eyes on day 0 (N =12) The right eyes of other BALB/c mice received 360° incisions and C57BL/6 corneal allografts were transplanted to the left eyes one day later, but the mice were not treated with α-MSH (N= 19). P>0.05. B) BALB/c mice were either untreated (N= 10) or treated with α-MSH (2μg; i.p.)(N = 12) beginning on day -1 and continuing every 3 days thereafter for 15 days. This experiment was performed twice with similar results.

Blockade of SP prevents the loss of immune privilege in hosts subjected to circular corneal incisions but does not enhance immune privilege in naïve hosts

The observation that Spantide II treatment restored immune privilege that was lost by severing corneal nerves suggested that perhaps blocking SP would enhance immune privilege in mice with intact corneal nerves or create immune privilege in mouse strains that do not express immune privilege of corneal allografts. Accordingly, naive BALB/c mice were treated with Spantide II prior to and after receiving C57BL/6 corneal allografts. However, administration of Spantide II did not enhance corneal allograft survival in naïve BALB/c mice (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Blockade of SP does not enhance immune privilege of first-time corneal allografts.

A) C57BL/6 corneal allografts were transplanted to BALB/c mice that were either treated with Spantide II or were injected with vehicle (untreated). Spantide II was administered i.p. at a dose of 36 μg/day beginning one day prior to the creation of circular incision and continued until day 60 post transplantation. N= 10; MST = 34 for untreated group; N= 8; MST = 30 for Spantide II treated group. P >0.05. B) BALB/c corneal allografts were transplanted to either C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice; N=20 or SP−/− (SP KO) mice; N=9. P>0.05. These experiments were performed twice with similar results.

Although C57BL/6 corneal allografts enjoy immune privilege when transplanted to BALB/c mice, BALB/c corneal allografts do not experience immune privilege in the C57BL/6 host, as shown by the 90% incidence of rejection that routinely occurs in BALB/c corneal allografts transplanted to C57BL/6 hosts (27). Accordingly, we tested the hypothesis that the C57BL/6 mouse might have elevated baseline levels of SP that prevent the establishment of immune privilege. However, 100% of the BALB/c corneal allografts transplanted to either SP KO mice (C57BL/6 background) or C57BL/6 wild-type mice underwent rejection (Figure 6B). Thus, blockade of SP does not enhance immune privilege in BALB/c hosts or promote immune privilege in C57BL/6 mice.

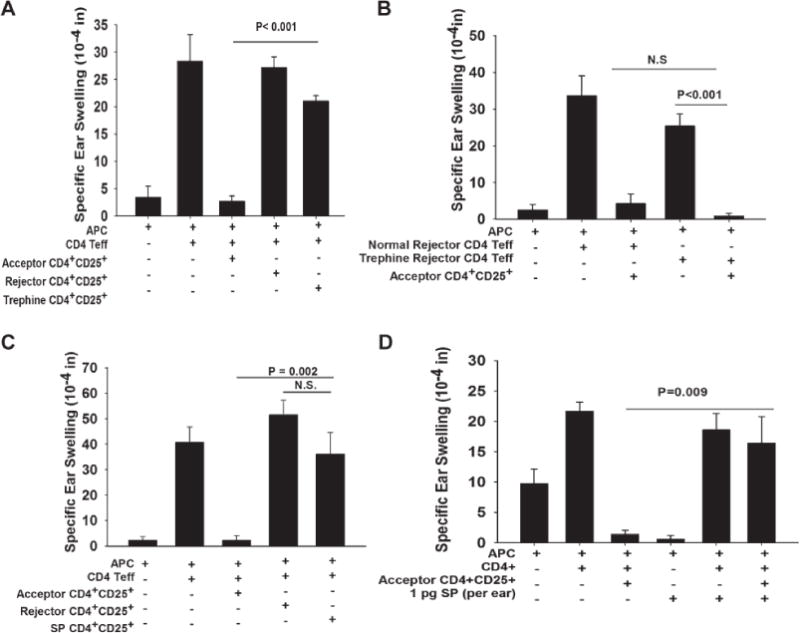

Immune privilege of corneal allografts relies on CD4+CD25+ T regs that suppress DTH to donor alloantigens (14, 16). The effect of SP on corneal allograft-induced Tregs was tested in a local adoptive transfer (LAT) of DTH assay in which CD4+CD25+ T cells from mice with long-standing corneal allografts were mixed with CD4+ DTH effector T cells from graft rejectors and APC’s pulsed with C57BL/6 alloantigens, which were then injected into the ears of naïve mice. CD4+CD25+ putative T regs from mice with surviving corneal allografts suppressed anti-C57BL/6 DTH responses, while CD4+CD25+ T cells from mice treated with a circular corneal incision prior to receiving a corneal allograft in the other eye failed to suppress DTH (Figure 7A). However, CD4+ effector T cells from mice receiving circular incisions and grafted were susceptible to T reg suppression (Figure 7B) indicating that the loss of immune privilege was due to a failure to generate T regs rather than generating CD4+ T cells that were refractory to T regs (Figure 7B). As shown earlier, the loss of T reg function could be mimicked by either subconjunctival or i.v. injection of SP, which resulted in >90% allograft rejection (Figures 4E – 4G), and a failure to develop functional CD4+CD25+ T cells (Figure7C). SP prevented the generation of T regs in grafted mice and blocked the function of CD4+CD25+T regs, as addition of SP to LAT assay injections abolished the suppressive activity of CD4+CD25+T regs (Figure 7D). SP acted on Tregs and did not simply enhance ear swelling responses by CD4+ T effector cells (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. SP induced by the severing of corneal nerves prevents the generation of T regs in corneal grafted hosts.

A) CD4+ CD25+ T cells from BALB/c mice that had accepted C57BL/6 corneal allografts, rejector mice, or BALB/c mice that had been treated with circular incisions and that rejected C57BL/6 corneal allografts on the contralateral eye were tested for suppressive activity in a conventional LAT assay. B) CD4+ T cells were isolated from untreated BALB/c mice or mice subjected to 360° corneal incisions (trephine) fourteen days prior to receiving C57BL/6 corneal allografts on the opposite eye and were tested in a LAT assay using CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells from graft acceptor mice. C) CD4+ CD25+ T cells were isolated from untreated BALB/c mice or mice injected subconjunctivally with SP (1.0 pg) one day prior to corneal transplantation in the other eye. CD4+CD25+ T cells from untreated graft acceptor mice, untreated graft rejector mice, and SP-treated mice (100% graft rejection) and were tested in a LAT assay. D) CD4+ CD25+ T cells were isolated from naïve BALB/c mice that had surviving C57BL/6 corneal allografts on day 30 and used in a LAT assay. SP (1.0 pg) was co-injected into the ears along with the other cells to determine if T reg suppression would be abolished. All experiments were performed twice with similar results. N=5 mice/group.

Foxp3, CTLA-4, GITR, and TGF-β1 are necessary for the suppressive function of corneal allograft-induced T regs (16, 17). CD4+CD25+ T cells from mice subjected to trephining prior to corneal transplantation did not display a significant change in Foxp3, CTLA-4, or TGF-β1 expression compared to mice not subjected to trephining (Figure 8A and B). However, GITR expression was reduced by >75% in the CD4+CD25+ T cells in mice subjected to trephining prior to corneal transplantation.

Figure 8. Effect of circular corneal incisions on the expression of CTLA-4, GITR, TGF-β1, and Foxp3 in CD4+CD25 T cells.

A) FACS profile for T reg markers. B) % of cells expressing T reg markers. 360° corneal incisions (trephine) were made in the left eyes of BALB/c mice on day 0 and C57BL/6 corneal allografts were transplanted to the right eye 14 days later. Untreated mice that did not reject their corneal allografts by day 21 were deemed to be “acceptors”. CD4+CD25+ T cells were isolated from the spleens 21 days after transplantation and examined by flow cytometry for cell surface expression of CTLA-4, GITR, or TGF-β and cytoplasmic expression of Foxp3. These experiments were performed twice with similar results.

Discussion

In human subjects corneal allografts are performed without HLA typing and with topical application of corticosteroids serving as the only anti-rejection therapy. However, the immune privilege of corneal allografts erodes with the application of a second or third corneal transplant, leading to a 3-fold increase in rejection (4). This can occur even in patients whose first corneal transplant is clear at the time when the second corneal transplant is placed onto the opposite eye (28). It is widely assumed that the elevated risk for graft rejection in hosts who receive a second corneal transplant is because the patients have been sensitized to the histocompatibility antigens expressed on the first graft, which are believed to also be expressed on the second graft. However, in the United States corneal buttons used for grafting are routinely selected at random without HLA typing thereby making this an unlikely explanation. As shown here, the immune privilege of second corneal allografts is abolished in hosts that receive an initial corneal graft, even a syngeneic corneal graft, which does not display alloantigens or tissue-specific antigens that can sensitize the host. In these settings, second syngeneic corneal allografts remain clear and are accepted indefinitely, while unrelated corneal allografts are invariably rejected. The most plausible explanation for the heightened incidence of corneal allograft rejection in hosts receiving a second allograft is that the severing of corneal nerves that occurs during surgery elicits a sympathetic burst of SP in the opposite eye, which disables T regs that are necessary for the survival of subsequent corneal allografts, which in turn, results in a sympathetic loss of immune privilege. Although T regs employ multiple molecules to suppress alloimmune responses, CTLA-4, GITR, and TRG-β1 appear to be indispensible for corneal allograft survival (16, 17). The present results indicate that circular incisions and SP elicit a down-regulation of GITR expression on CD4+C25+ T regs in mice receiving corneal allografts. This is in keeping with previous reports regarding the role of GITR in corneal allograft survival (16, 17). GITRL is constitutively expressed on the cornea and in vitro exposure of naïve CD4+ T cells with GITRL+ corneas results in the generation of T regs (17). Moreover, long-standing corneal allografts contain Foxp3+, GITR+ CD4+CD25+ T cells. GITR is crucial for corneal allograft survival, as administration of anti-GITRL antibody results in 100% corneal graft rejection (17).

Although patients receiving second and third corneal transplants experience a 3-fold increase in the incidence of immune rejection, approximately 30% will succeed (4). This 30% acceptance of subsequent corneal transplants might be related to the liberal use of corticosteroids in corneal transplantation patients, especially those at high risk for rejection. In addition to their immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties, corticosteroids can also counter the untoward effects of SP. Corticosteroids down regulate tachykinin receptors and neuropeptide synthesis in neurons and immune cells (29) and also up-regulate the synthesis of neuropeptide-degrading enzymes (30), while decreasing the levels of SP in the tears (31).

Laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) is one of the most common surgical procedures performed in the U.S., with eight million LASIK surgeries occurring since its FDA approval in 1995. LASIK involves circumferential incisions similar to those performed in the present study and results in a steep reduction in corneal nerve density that can persist for 5 or more years (32). One might predict that patients who have received LASIK surgery represent a large pool at risk for corneal transplant rejection. However, the leading indications for receiving a corneal transplant are keratoconus, corneal opacification and interstitial keratitis, and repeat corneal transplants. Each of these conditions will disqualify a patient from undergoing LASIK surgery. Thus, one can only speculate as to whether LASIK patients have a heightened risk for corneal graft rejection.

Our findings also indicate that the severing of corneal nerves and the ensuing release of SP that occurs during the first corneal transplantation procedure does not affect the initial development of Tregs or the survival of the initial corneal transplant, but does block the subsequent generation and function of T regs that are necessary for the acceptance of second and third corneal allografts. This proposition is supported by results with SP KO mice, which did not display a heightened acceptance of first time corneal allografts. However, the release of SP pursuant to cornea nerve damage may explain the heightened rejection that occurs in patients who receive a second corneal transplant; including those patients whose first transplant displayed no evidence of rejection prior to the application of the second graft (4). This is analogous to punching a ticket when one boards a train. The ticket (Tregs) allows a one-time pass but is invalidated for subsequent trips (transplants).

The capacity of a single bolus injection of 1.0 pg of SP to abolish immune privilege of corneal allografts for at least 100 days is puzzling considering that the serum half-life of SP is less than two minutes (33). Moreover, serum levels of SP dissipate to baseline levels 5 hours after trephining the cornea (unpublished data). We speculate that SP permanently imprints a population of long-lived immune cells, such as memory T cells, that have the capacity to disable Tregs. Long term investigations are underway to test this hypothesis.

SP also contributes to the loss of ocular immune privilege in other settings. Antigens injected into the AC of the eye induce a form of immune tolerance called anterior chamber-associated immune deviation (ACAID), which is characterized by the generation of Tregs that suppresses DTH responses in an antigen-specific manner (5). However, simultaneous AC injection of antigen and SP prevents the induction of ACAID (26). It is noteworthy, that AC injection of alloantigens induces ACAID and reduces the incidence of immune rejection of subsequent corneal allografts (34–36). Two inflammatory diseases of the eye are known to increase the incidence and tempo of corneal allograft rejection, herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis (37) and allergic conjunctivitis (38, 39). Both HSV keratitis and allergic conjunctivitis are associated with increased levels of SP in the cornea and tears respectively and both are associated with a loss of immune privilege and corneal allograft rejection (40, 41).

It is widely believed that ocular immune privilege is an adaptation to minimize immune-mediated inflammation of ocular tissues that have little or no capacity for regeneration. We are attracted to the hypothesis that the extraordinary density of sensory nerves in the cornea is an adaptation to trigger avoidance responses to physical trauma that could damage the eye. Damaging corneal nerves would also transmit a “danger” signal in the form of SP that abolishes immune privilege and promotes protective immune responses to potentially life-threatening microbial agents that infect the ocular surface. The release of SP in both eyes in response to mechanical injury (e.g., damage or severing of corneal nerves) or viral infection in one eye would terminate immune privilege in both eyes and thereby allow the emergence of a protective immune response to infectious agents that might eventually affect both eyes. In the end we are reminded that ocular immune privilege most likely evolved to reduce immune-mediated injury to ocular tissues and preserve vision. Corneal transplants are beneficiaries of this adaptation but nonetheless, must obey the ground rules of immune privilege.

Acknowledgments

This work supported by NIH grants EY007641 and EY020799 and Research to Prevent Blindness. We thank Dr. Khrishen Cunnusamy for helpful advice on flow cytometry.

Abbreviations

- ACAID

anterior chamber-associated immune deviation

- α-MSH

α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related protein

- DTH

delayed-type hypersensitivity

- SLIP

sympathetic loss of immune privilege

- SP

substance P

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

Footnotes

Disclosure

This manuscript was not prepared or funded by a commercial organization. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

References

- 1.George AJ, Larkin DF. Corneal transplantation: the forgotten graft. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(5):678–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niederkorn JY. Corneal transplantation and immune privilege. Int Rev Immunol. 2013;32(1):57–67. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2012.737877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Group CCT. Effectiveness of histocompatibility matching in high-risk corneal transplantation. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1992;110:1392–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coster DJ, Williams KA. The impact of corneal allograft rejection on the long-term outcome of corneal transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1112–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niederkorn JY. See no evil, hear no evil, do no evil: the lessons of immune privilege. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(4):354–359. doi: 10.1038/ni1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niederkorn JY. High-risk corneal allografts and why they lose their immune privilege. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2010;10(5):493–497. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833dfa11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albuquerque RJ, Hayashi T, Cho WG, Kleinman ME, Dridi S, Takeda A, et al. Alternatively spliced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 is an essential endogenous inhibitor of lymphatic vessel growth. Nature medicine. 2009;15(9):1023–1030. doi: 10.1038/nm.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Hamrah P, Cursiefen C, Zhang Q, Pytowski B, Streilein JW, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 mediates induction of corneal alloimmunity. Nature medicine. 2004;10(8):813–815. doi: 10.1038/nm1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cursiefen C, Chen L, Borges LP, Jackson D, Cao J, Radziejewski C, et al. VEGF-A stimulates lymphangiogenesis and hemangiogenesis in inflammatory neovascularization via macrophage recruitment. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113(7):1040–1050. doi: 10.1172/JCI20465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hori J, Wang M, Miyashita M, Tanemoto K, Takahashi H, Takemori T, et al. B7-H1-induced apoptosis as a mechanism of immune privilege of corneal allografts. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):5928–5935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen L, Jin Y, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH, Dana MR. The function of donor versus recipient programmed death-ligand 1 in corneal allograft survival. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):3672–3679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stuart PM, Griffith TS, Usui N, Pepose J, Yu X, Ferguson TA. CD95 ligand (FasL)-induced apoptosis is necessary for corneal allograft survival. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;99(3):396–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI119173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamagami S, Kawashima H, Tsuru T, Yamagami H, Kayagaki N, Yagita H, et al. Role of Fas-Fas ligand interactions in the immunorejection of allogeneic mouse corneal transplants. Transplantation. 1997;64(8):1107–1111. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199710270-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chauhan SK, Saban DR, Lee HK, Dana R. Levels of Foxp3 in regulatory T cells reflect their functional status in transplantation. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):148–153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cunnusamy K, Chen PW, Niederkorn JY. IL-17 promotes immune privilege of corneal allografts. Journal of Immunology. 2010;185(8):4651–4658. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunnusamy K, Chen PW, Niederkorn JY. IL-17A-dependent CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells promote immune privilege of corneal allografts. J Immunol. 2011;186(12):6737–6745. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hori J, Taniguchi H, Wang M, Oshima M, Azuma M. GITR ligand-mediated local expansion of regulatory T cells and immune privilege of corneal allografts. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2010;51(12):6556–6565. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He YG, Mellon J, Niederkorn JY. The effect of oral immunization on corneal allograft survival. Transplantation. 1996;61(6):920–926. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199603270-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sano Y, Ksander BR, Streilein JW. Murine orthotopic corneal transplantation in high-risk eyes. Rejection is dictated primarily by weak rather than strong alloantigens. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1997;38(6):1130–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lighvani S, Huang X, Trivedi PP, Swanborg RH, Hazlett LD. Substance P regulates natural killer cell interferon-gamma production and resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(5):1567–1575. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashour HM, Niederkorn JY. Expansion of B cells is necessary for the induction of T-cell tolerance elicited through the anterior chamber of the eye. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2007;144(4):343–346. doi: 10.1159/000106461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozsa AJ, Beuerman RW. Density and organization of free nerve endings in the corneal epithelium of the rabbit. Pain. 1982;14(2):105–120. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(82)90092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asahina A, Hosoi J, Beissert S, Stratigos A, Granstein RD. Inhibition of the induction of delayed-type and contact hypersensitivity by calcitonin gene-related peptide. J Immunol. 1995;154(7):3056–3061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor AW, Streilein JW, Cousins SW. Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone suppresses antigen-stimulated T cell production of gamma-interferon. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1994;1(3):188–194. doi: 10.1159/000097167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor AW, Streilein JW, Cousins SW. Immunoreactive vasoactive intestinal peptide contributes to the immunosuppressive activity of normal aqueous humor. J Immunol. 1994;153(3):1080–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson TA, Fletcher S, Herndon J, Griffith TS. Neuropeptides modulate immune deviation induced via the anterior chamber of the eye. Journal of Immunology. 1995;155(4):1746–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegde S, Beauregard C, Mayhew E, Niederkorn JY. CD4(+) T-cell-mediated mechanisms of corneal allograft rejection: role of Fas-induced apoptosis. Transplantation. 2005;79(1):23–31. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000147196.79546.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams KA, Kelly TL, Lowe MT, Coster DJ. The influence of rejection episodes in recipients of bilateral corneal grafts. American journal of transplantation: official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2010;10(4):921–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adcock IM, Peters M, Gelder C, Shirasaki H, Brown CR, Barnes PJ. Increased tachykinin receptor gene expression in asthmatic lung and its modulation by steroids. J Mol Endocrinol. 1993;11(1):1–7. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0110001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graf K, Schaper C, Grafe M, Fleck E, Kunkel G. Glucocorticoids and protein kinase C regulate neutral endopeptidase 24.11 in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Basic Res Cardiol. 1998;93(1):11–17. doi: 10.1007/s003950050056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Callebaut I, Vandewalle E, Hox V, Bobic S, Jorissen M, Stalmans I, et al. Nasal corticosteroid treatment reduces substance P levels in tear fluid in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;109(2):141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Erie JC, McLaren JW, Hodge DO, Bourne WM. Recovery of corneal subbasal nerve density after PRK and LASIK. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(6):1059–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schaffalitzky De Muckadell OB, Aggestrup S, Stentoft P. Flushing and plasma substance P concentration during infusion of synthetic substance P in normal man. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 1986;21(4):498–502. doi: 10.3109/00365528609015169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niederkorn JY, Mellon J. Anterior chamber-associated immune deviation promotes corneal allograft survival. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1996;37(13):2700–2707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.She SC, Moticka EJ. Ability of intracamerally inoculated B- and T-cell enriched allogeneic lymphocytes to enhance corneal allograft survival. Int Ophthalmol. 1993;17(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00918860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.She SC, Steahly LP, Moticka EJ. Intracameral injection of allogeneic lymphocytes enhances corneal graft survival. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 1990;31(10):1950–1956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Easty D, Entwistle C, Funk A, Witcher J. Herpes simplex keratitis and keratoconus in the atopic patient. A clinical and immunological study. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1975;95(2):267–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beauregard C, Stevens C, Mayhew E, Niederkorn JY. Cutting edge: atopy promotes Th2 responses to alloantigens and increases the incidence and tempo of corneal allograft rejection. J Immunol. 2005;174(11):6577–6581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flynn TH, Ohbayashi M, Ikeda Y, Ono SJ, Larkin DF. Effect of allergic conjunctival inflammation on the allogeneic response to donor cornea. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2007;48(9):4044–4049. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sacchetti M, Micera A, Lambiase A, Speranza S, Mantelli F, Petrachi G, et al. Tear levels of neuropeptides increase after specific allergen challenge in allergic conjunctivitis. Mol Vis. 2011;17:47–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Twardy BS, Channappanavar R, Suvas S. Substance P in the corneal stroma regulates the severity of herpetic stromal keratitis lesions. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2011;52(12):8604–8613. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]