Abstract

Cells respond to mechanical stimulation by activation of specific signaling pathways and genes that allow the cell to adapt to its dynamic physical environment. How cells sense the various mechanical inputs and translate them into biochemical signals remains an area of active investigation. Recent reports suggest that the cell nucleus may be directly implicated in this cellular mechanotransduction process. In this chapter, we discuss how forces applied to the cell surface and cytoplasm induce changes in nuclear structure and organization, which could directly affect gene expression, while also highlighting the complex interplay between nuclear structural proteins and transcriptional regulators that may further modulate mechanotransduction signaling. Taken together, these findings paint a picture of the nucleus as a central hub in cellular mechanotransduction—both structurally and biochemically—with important implications in physiology and disease.

Keywords: mechanics, forces, signaling, lamins, LINC complex

Introduction

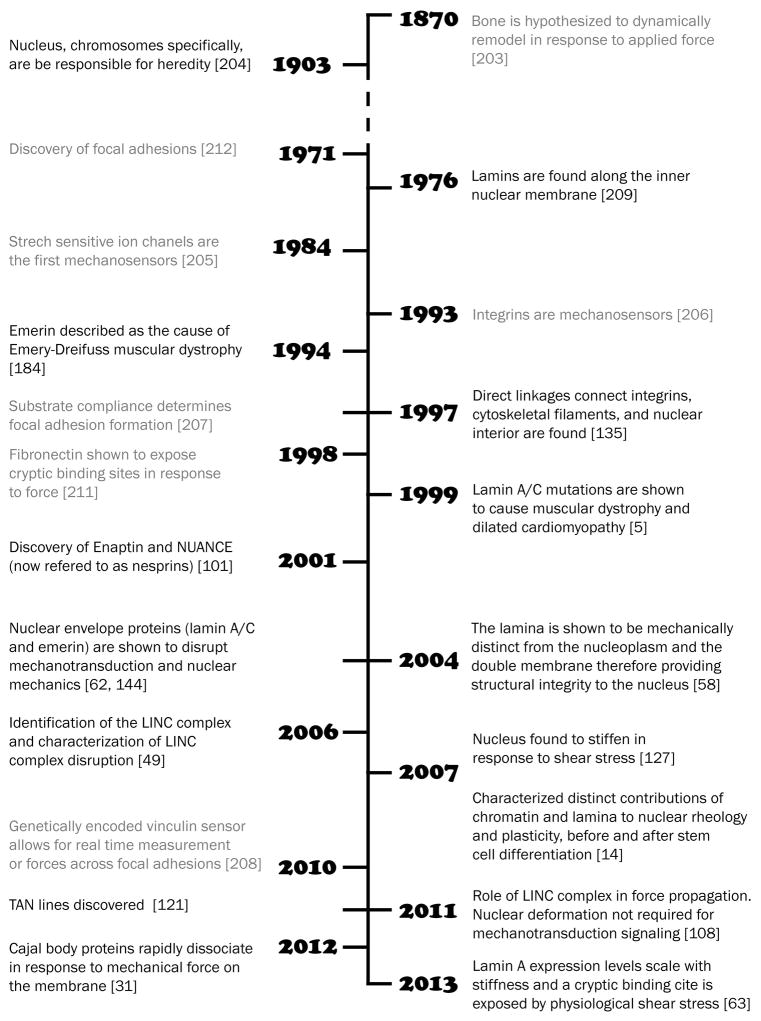

The nucleus, often considered the “brain” of the cell, contains the cell’s vast genome. The nucleus is primarily responsible for regulating gene expression, which in turn controls the instructions for protein synthesis. This transcriptional and translational mechanism enables cells to respond to mechanical, and other, stimuli. Initiating the appropriate mechano-response necessitates the nucleus correctly interpreting the type, duration, and magnitude of the signals it receives. These signals can be biochemical, stemming from signaling cascades that started at the cell membrane and cytoskeleton, or they can be mechanical, reaching the nucleus through direct force transmission. Highlighting the importance of the nucleus in mechanotransduction is the fact that defects in the function of the nucleus can result in misregulated expression of mechanosensitive genes, even if the rest of the cell is functioning properly. Thanks to groundbreaking research conducted over the past three decades, much is known about how integrins and focal adhesions respond to substrate stiffness, strain, and other mechanical stimuli, as discussed in detail in the previous chapters. For the nucleus, such insights are only beginning to emerge. It is now evident that the nucleus plays a vital role in cellular mechanotransduction, even though many questions still surround its specific function(s). Specifically, is the nucleus merely a puppet to the surrounding cytoplasm, relaying biochemical signals into changes in gene expression? Or does the “brain of the cell” have a mind of its own when it comes to sensing mechanical inputs? These questions make up the two main hypotheses regarding the role of the nucleus, and its associated proteins and structures, in cellular mechanoresponse.1 The first scenario is that the nucleus has the primary role of transcriptional regulation in response to biochemical signals coming from the rest of the cell, with little direct involvement in the actual sensing of mechanical forces. In the second scenario, the nucleus is the final element in a cellular Rube Goldberg machine that consists of a chain of structural, force propagating elements which induce nuclear deformations that directly translate into gene expression instructions. Distinguishing between these two scenarios is a major question in mechanobiology, and the answer likely lies somewhere in between these extremes.

Before investigating the role of the nucleus in mechanotransduction, we need to define the components and processes of the cellular mechanoresponse. A transducer, by definition, is a device that converts one form of energy into another. There are numerous transducers that we interact with in everyday life; for instance, a loud speaker transduces electrical energy into sound waves, and an electric motor transduces electricity into mechanical energy, i.e. motion. In the context of the cell, we will refer to the specific structure (protein or other molecule) that transduces mechanical signals into biochemical signals as the ‘mechanotransducer’, or, to avoid any confusion, the ‘mechanosensor’. While technically mechanotransduction only describes the immediate process of converting a mechanical signal into a biochemical signal, the term ‘mechanotransduction’ is often also understood to include the downstream biochemical signaling from a mechanosensor. Furthermore, in the literature, ‘mechanotransduction’ is also used to describe any cellular change in response to a mechanical stimuli, for example, the alignment of endothelial cells in response to fluid shear stress, or the adaptation of bone density to microgravity or physical activity. In this chapter, we use the term ‘mechanotransduction signaling’ to include both the initial mechanosensing event as well as the biochemical signaling downstream of the mechanosensor. Complementary to the intracellular propagation of biochemical signals is the process of propagating physical forces through the cell; we will call the structures involved in this process ‘mechanotransmitters’. Importantly, based on the definition used here, a given protein could be involved in mechanotransduction signaling without itself being a mechanosensor.

Historically, research in mechanotransduction has attempted to find the cellular mechanosensor; it is now becoming apparent that there are numerous mechanosensors in the cell, ranging from stretch sensitive channels in the plasma membrane to cytoplasmic proteins that undergo conformational changes in response to force.2 Several recent studies support the idea of the nucleus being one such cellular mechanosensor, as discussed in detail below. At the same time, it is important to recognize that even if the nucleus may not directly sense mechanical stimuli, it certainly has a key role in regulating the cellular mechanoresponse via both physical force transmission and processing biochemical signals.

Although the specific function of the nucleus in cellular mechanotransduction is still incompletely understood, it is well established that mutations in numerous nuclear envelope proteins cause both defects in mechanotransduction signaling and force transmission.3,4 These mutations can cause muscular dystrophy, dilated cardiomyopathy, partial familial lipodystrophy, cancer, and the accelerated aging disease Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, among others. Many of these diseases are caused by mutations in a nuclear envelope protein, lamin A/C, which is encoded by the LMNA gene. To date, more than 450 disease-causing mutations have been discovered in the LMNA gene alone, with the vast majority of mutations affecting striated muscle, i.e., mechanically stressed tissues (http://www.umd.be/LMNA). In the case of the LMNA gene, the specific effects of subtle differences between these mutations on the resulting disease are fascinating. For instance, changing a single amino acid in lamin A/C at position 528 from threonine to lysine causes muscular dystrophy, while changing the identical amino acid position to methionine results in lipodystrophy symptoms5,6. Equally interesting is the fact that similar disease phenotypes can often be caused by mutations in one of multiple proteins (e.g., mutations in either lamins, emerin, nesprins, or the cytoskeletal protein dystrophin all cause muscular dystrophy). This suggests that these proteins are all involved in similar cellular functions, e.g., force transmission, mechanical stability, or mechanotransduction, and highlights the importance of intact force transmission and mechanotransduction pathways in cellular function. An improved understanding of the role of the nucleus in mechanotransduction would not only lead to better insights into normal cell biology but may also pave the way for novel therapies for the many diseases caused by mutations in nuclear (envelope) proteins.

Overview of Nuclear Structure and Organization

As the age old maxim goes, structure imparts function. Like a mechanic fixing a car without understanding how the engine is built and connected to the rest of the car, trying to decipher the role of the nucleus in mechanotransduction and disease necessitates an understanding of nuclear structure and its connection to the cytoskeleton. Given the relevance to human disease, we restrict our discussion to mammalian cells. In eukaryotic cells, the nucleus not only houses the genome, but also transcriptional machinery, thus allowing it to act as the central processing center of incoming signals. The nucleus is typically the largest cellular organelle. It is separated from the surrounding cytoplasm by two lipid membranes and the underlying nuclear lamina meshwork which provides structural support. Together the membranes, lamina, and associated proteins make up the nuclear envelope, which also mechanically connects the cytoskeleton to the nuclear interior.7 As the nucleus is substantially stiffer than the surrounding cytoplasm, the mechanical properties of the nucleus significantly contribute to the overall cell deformability and the transmission of forces across the cell. In the following, we provide a brief description of the structural and mechanical components of the cell nucleus, from the nuclear interior to the outer nuclear membrane and the proteins linking the nucleus to the cytoskeleton. These sections will illustrate that the nucleus is connected to the cellular environment by a continuous physical chain via the cytoskeleton, focal adhesions, and cell-cell junctions (Fig. 1). Consequently, forces from the extracellular matrix, neighboring cells, and the cytoskeleton can be transmitted directly to the nucleus, where they can induce substantial structural changes 8.

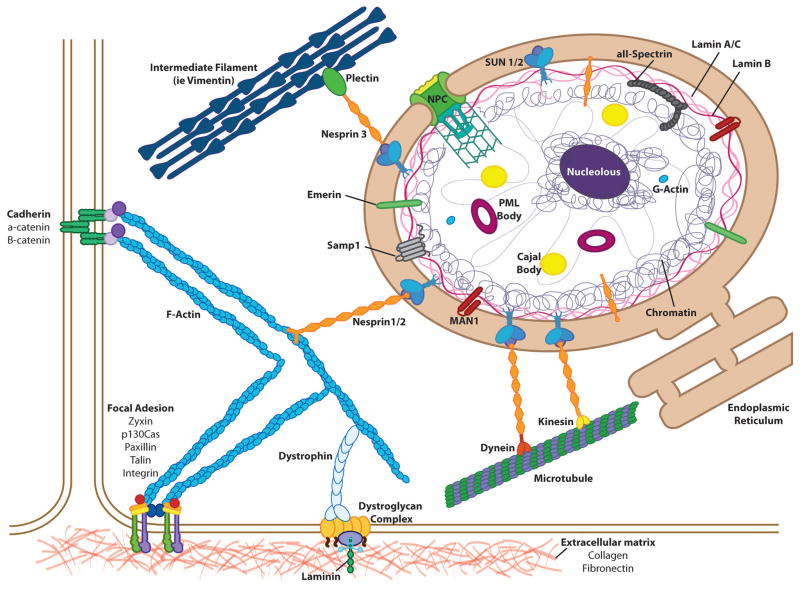

Figure 1. Cellular connectivity.

The genome is connected to the extracellular environment through an array of proteins. The nucleoplasm houses the chromatin, and subnuclear bodies (nucleolus, Cajal bodies, and PML bodies). The chromatin associates with the nuclear lamina along the inner nuclear membrane, where it also interacts with LEM domain proteins. Reaching across the luminal space, SUN proteins on the inner nuclear membrane bind to the KASH domains of nesprins to form the LINC complexes that link the nuclear interior to the cytoskeleton filaments (actin, intermediate filaments, and microtubules), often through intermediary linker proteins such as plectin, dynein, or kinesin. The cytoskeletal filaments connect to cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions, completing the physical connection from genome to extracellular environment.

Chromatin and chromosome territories

Long, contiguous DNA polymers are packaged into discrete units called chromosomes, which are made of chromatin, a fibrous combination of DNA and DNA-binding proteins. The most prominent of these proteins are histones; histone polypeptides facilitate the efficient packing of two meters of human DNA into a ≈10 μm-diameter nucleus.9 This stunning packaging is achieved by winding the DNA like thread around a histone spool. Histones H2A and H2B, and H3 and H4, unite as heterodimers to form octamer “beads” that are—together with the wound DNA—called nucleosomes. The odd-histone out, histone H1, helps link nucleosomes together and stabilize higher-order structures. Histones are well suited to transmit signals directly to the genome through a plethora of covalent biochemical modifications such as acetylation, phosphorylation, methylation, poly-ADP-ribosylation, ubiquination, and SUMOylation which affect the structure and transcriptional activity of chromatin without altering the DNA sequence.10,11 Broadly speaking, chromatin exists in two states, (1) the more transcriptionally active, more loosely organized euchromatin, which typically localizes to central regions of the nucleus, and (2) the transcriptionally inactive, more densely packed heterochromatin, which inhabits the nuclear periphery and the area surrounding nucleoli.12 DNA-binding dyes such as DAPI or Hoechst stain compact heterochromatin darker than its euchromatic counterpart. Euchromatin and heterochromatin can also be easily distinguished in transmission electron micrographs.9

The differences in chromatin compaction have important implications for deformation under force. Studies on isolated nuclei have shown that the nuclear interior, chromatin in particular, substantially contributes to the mechanical property of the nucleus.13 Both condensed and non-condensed chromatin behave as complex viscoelastic fluids but demonstrate plastic changes after ≈10 seconds of stress in micropipette aspiration experiments.14 In addition, condensed chromatin is substantially less deformable than non-condensed chromatin,14 suggesting that the higher packing density limits further compaction. Importantly, the nucleoplasm is ≈2-to 10-times stiffer than the cytoplasm and resists further compression after being compacted more than 60%.15,16,17 The “compression limit” is one contributor to chromatin’s, and especially heterochromatin’s, ability to bear up to 50% of the load applied to the nucleus,14,18 and may become highly relevant when cells must deform during migration through tight interstitial spaces19. These findings illustrate the interrelation between chromatin and nuclear mechanics, and may hint at mechanisms by which force induced changes in chromatin structure could contribute to nuclear mechanosensing.

Recent technological advancements have enabled stunning views of the non-random chromosome organization (chromosome territories) within the interphase nucleus. For example, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques with multiple fluorescent probes have been used to construct a probability model of chromosome territories. Using FISH, Cremer et al. showed that chromosomes have preferential locations that do not become intermingled.20 Intriguingly, these territories appear to be relatively stable throughout mitosis.21 This non-random orientation could enable specific directional forces, such as shear stress, to consistently impact the same chromatin region. For instance, it has been shown that cytoskeletal filaments in endothelial cells stiffen in regions exposed to high levels of localized shear22. It is conceivable that these forces could then propagate to specific nuclear territories and potentially influence gene expression.

While the nuclear interior is primarily occupied by chromatin, is also contains other distinct structures such as nucleoli and Cajal bodies, as well as structural proteins such as lamins, actin, myosin, titin, and spectrin23,24 which will be discussed in the following.

Subnuclear structures and nuclear bodies

Interest in subnuclear organization stems from the desire to uncover links between structural changes and alterations in gene expression and cell signaling. The most prominent subnuclear structures are nucleoli, which appear as dark spots in the nuclear interior by phase contrast light microscopy. Nucleoli are dynamic nuclear bodies primarily responsible for ribosome biogenesis. They are the largest subnuclear compartments and are functionally separate from the rest of the nucleus. When the nucleus is subjected to mechanical stress, nucleoli also undergo plastic deformations.14

In addition to nucleoli, the majority of mammalian nuclei contain 5 to 30 protein-based compartments called promyelocytic leukaemia nuclear bodies (PML-NBs), which play a role in transcription, DNA damage repair, and nuclear response to viral infection.25–27 PML-NBs show dynamic changes in number and size when cells are exposed to various stresses, such as heat shock and heavy metal exposure. However, their response to mechanical stress has not been well characterized.28,29 This could yield interesting results given the specific interactions between PML-NBs and certain chromosomal loci.26 In addition, a highly dynamic class of PML-NBs moves in an ATP-dependent fashion and may utilize nuclear actin and myosin in order to rapidly traverse the nucleus, further linking PML-NBs to mechanoresponsive elements.27,30

Cajal Bodies (CBs) are 0.5 – 1 μm diameter subnuclear domains which feature two major multi protein-mRNA complexes characterized by Survival of Motor Neuron (SMN) and coilin.31,32 Their main function is to assemble and modify ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) important in pre-mRNA splicing, telomere formation and histone mRNA processing.33 The number of these structures is a function of both cell type and cell cycle. CBs are more frequently seen in cells with high transcriptional demands (e.g., neurons, skeletal muscle cells, cancer cells), while in others cell types they may not be visible at all (skin epidermal cells, cardiac and smooth muscle cells).32,34,35 Like PML-NBs, CBs are highly stress-responsive to viral infection and radiation, among others. Linking to the genome, CBs associate dynamically with chromatin and they are mobile structures with their interactions and localization being influenced by phosphorylation.33,36 As discussed in detail later, recent findings suggest that mechanical forces transmitted across the nuclear envelope may also affect CB structure and function.31

The nucleoskeleton

For decades, researchers have sought to characterize the putative nucleoskeleton as either an active framework, a passive framework, or an artifact.23,37 The existence of simple, cell-free technologies to replicate and transcribe DNA proves that many of the quintessential functions of the nucleus can be carried out without higher order structures (i.e. nucleoskeletal elements). At the same time, a nucleoskeletal framework or scaffold could help organize chromosome territories as well as position the transcriptional machinery and regulatory complexes. Relating back to mechanosensing, a dynamic, well-networked nucleoskeleton has the potential to directly couple extracellular forces to the genome. A prominent class of nucleoskeletal proteins are lamins, which exist as both a solid-like meshwork at the periphery and may form stable structures with transcription factors and other molecules in the interior.38 Lamins and their interaction partners will be discussed in detail later.

In addition to specialized nuclear proteins, recent findings suggest that many proteins traditionally found in the cytoskeleton, such as spectrin II-alpha, titin, 4.1R, myosin, and actin, have roles in the nucleus as well.39,40 The organization of these proteins in the nucleus remains uncertain – they may form a structural scaffold throughout the nuclear interior, or they may form a peripheral network supporting the nuclear envelope.24 Spectrin II-alpha and titin are cross-linking proteins known for their large size and elasticity. Consistent with these characteristics, nuclei that lack spectrin II-alpha have difficulty recovering from swelling and stretching.40 Beyond its mechanical function, spectrin II-alpha is also important for DNA repair,41 demonstrating how structural and regulatory roles often overlap in the nucleus.12,40 Titin, normally found in muscle sarcomeres, has been shown to also interact with lamins both in vitro and in vivo. Structurally, loss of titin results in large nuclear blebs.42

One particularly important player that is beginning to emerge in this context is nuclear actin. The presence of actin in the nucleus, a once hotly-contested subject, is now widely accepted.30,43 Actin exists as either monomeric G-actin or polymeric F-actin and is ubiquitously-expressed in virtually all eukaryotic cells. In the nucleus, monomeric actin is highly active throughout transcription and has many interaction partners, including RNA polymerase I-III and certain transcription factors.30 Exciting new fluorescent probes can now distinguish between monomeric (RPEL1 motif-probes) and filamentous (Lifeact-NLS and Utr230-based probes) nuclear actin in living cells, showing distinct localization patterns and kinetics of these molecules.30,44 Immunofluorescence studies indicate that Utr230-actin reporters distribute throughout the interchromatin space and neither colocalize with chromatin remodelers, nor with traditional actin-associated proteins such as myosin I.44 The main purpose of filamentous nuclear actin could then be to contribute viscoelasticity, or a stabilizing meshwork, to the nuclear interior, similar to what is seen in Xenopus laevis oocytes.45 Regardless of its structural role, F-actin assembly by formins or other actin nucleators30 can control gene expression by freeing G-actin from the transcription factor MKL1 and enabling it to activate serum response factor (SRF) target genes, or alternatively, through modulating histone-acetyltransferases.30 The role of nuclear actin in signaling will be discussed in more detail later. In general, nuclear actin and the nucleoskeleton are no longer considered artifacts; however, the ways by which mechanical force affects nucleoskeletal proteins and their functions remains incompletely understood.12,23

Lamins, the nuclear lamina, and nuclear mechanics

Lamins and their associated proteins form a dense meshwork (nuclear lamina) along the inner nuclear membrane. The lamina interacts with inner nuclear membrane proteins, nuclear pore complexes, and the nuclear interior. Lamins are type V intermediate filaments that can be grouped into two classes: (1) A-type lamins, which are generated by alternatively splicing of the LMNA gene into lamin A and C and some less abundant isoforms, and (2) B-type lamins, which are encoded by the LMNB1 and LMNB2 genes, which produce lamin B1 and B2/B3, respectively.38 While A-type lamins and lamins B1 and B2 are expressed in almost all somatic cells, lamin B3 expression is restricted to germ cells. Lamin A and B-type lamins undergo extensive posttranslational processing at the C-terminus, including farnesylation and endoproteolytic cleavage. B-type lamins remain permanently farnesylated and thus attached to the inner nuclear membrane, even during mitosis.46 In contrast, lamin A undergoes an additional modification, where the protein Zmpste24 removes the farnesylated tail, resulting in mature lamin A. Lamin C, which has a distinct C-terminus, does not undergo the same processing and is not farnesylated.10 Mature lamin A and lamin C, which lack the hydrophobic farnesyl tail, can be found both in the nucleoplasm and the nuclear lamina.47

Lamins, which have a half-life of ≈13 hours, assemble into stable filaments.48 They form parallel dimers through coiled-coil interaction of their central rod domains.38 The dimers associate head-to-tail and then laterally assemble in an anti-parallel fashion into non-polar filaments with a final diameter of about 10 nm. In transmission electron micrographs of mammalian cells, the nuclear lamina is visible as a 25–50 nm thick dense protein layer underneath the inner nuclear membrane.17,49 The higher order structure of lamins in somatic cells is not completely understood due to the tight association of the lamina with chromatin, which makes high resolution imaging challenging.50 However, Xenopus oocytes do not pose the same challenges; electron micrographs in these cells show a lamin structure composed of a square lattice of ≈10-nm thick cross-linked filaments.50,51 Because of this, lateral interactions between dimers and proto-filaments are thought to be critical for maintaining the correct higher order structure. Based on mathematical modeling, correct coiling direction of the heptads appears to be important to allow for “unzipping” and subsequent attachment to adjacent strand.52 Mutations could result in increased or decreased stability due to incorrect assembly and/or binding.53 It is important to note that these ideas await experimental confirmation. Intriguingly, although different lamin isoforms can all interact and form heteropolymers in vitro, they typically segregate into homopolymers and form distinct, but overlapping, networks in vivo.54–57

Although there are still some questions about the filament and structural assembly of the lamina in vivo, the importance of nuclear lamins in contributing to nuclear stiffness and stability has been unequivocally established. Based on micropipette aspiration experiments on isolated Xenopus oocyte nuclei, which can be osmotically swollen to separate the chromatin from the nuclear lamin, the lamin network has an elastic modulus of ≈25 mN/m.58 For comparison, the plasma membrane of neutrophils has an elastic modulus of ≈0.03 mN/m and chondrocyte and endothelial cell membranes have a modulus of ≈0.5 mN/m.59 Using a variety of experimental approaches, the stiffness of the nucleus has been determined to be 2- to 10-times stiffer than the surrounding cytoplasm, depending on the particular cell-type and measurement method.16,60,61 When comparing the lysis strain of the nuclear envelope (i.e., the the nuclear lamina and the nuclear membranes) with that of a simple double lipid membrane to distinguish the contribution of the nuclear lamina, the lysis strain of the nuclear envelope was 12-fold higher than that of the standard double membrane system, highlighting the stabilizing impact of the nuclear lamina.58 Similarly, when a fluorescent dye is injected into the nucleus of living cells, cells that lack lamins A/C show dramatically increased rates of nuclear rupture compare to wild-type cells.62

Given this important role of lamins in conferring structural integrity to the nucleus, what is the contribution of the different types of lamins to nuclear mechanics? While B-type lamins are nearly ubiquitously and uniformly expressed among different cell-types and tissues, lamin A/C expression is highly tissue-specific. For instance, muscle cells and other mesenchymal cells typically are among the highest in A-type lamin expression levels.63,64 A recent study found that the ratios of A-type to B-type lamins in different tissues closely correlates with the tissue stiffness suggesting a mechanosensitive regulation of lamin levels,63 which could help protect the nucleus from mechanical stress by increasing mechanical stability.62 In cells that express both A-type and B-type lamins, lamins A and C are the major contributors to nuclear stability, with B-type lamins having a smaller role in overall nuclear stiffness.65 Nonetheless, there may be some functional redundancy between lamins regarding mechanical properties. For instance, introducing lamin B into lamin A-null cells can partially rescue mechanical defects.55,66 Furthermore, B-type lamins are important for nuclear anchoring to the cytoskeleton, particularly during neuronal migration/development in the brain, as these cells lack A-type lamins.67–70

Similarly, embryonic stem cells do not express A-type lamins until they begin to differentiate. Once they decrease their stemness, their nuclear stiffness increases up to 6-fold compared to the undifferentiated state. This is most likely due to the increased levels of lamins A/C in the new lineage and possibly changes in chromatin configuration.14,64 A few specialized differentiated cells, notably neutrophils and neurons, hardly express any A-type lamins even after differentiation.69,71 The lack of A-type lamins in embryonic stem cells, neutrophils, and neurons may facilitate migration, enabling these cells to travel through dense tissues and interstitial spaces during development and inflammation.72 For example, the decrease in lamin A/C levels along with the concomitant increase in expression of lamin B receptor (LBR) during granulopoiesis promotes the distinct highly lobulated nuclear shape of mature neutrophils.15 In addition, the low levels of lamin A result in a highly deformable nucleus allowing neutrophils to easily squeeze through small spaces.15 Similarly, regulation of lamin A/C levels may also regulate trafficking and lineage maturation of other hematopoietic cells types.73

In addition to changes in lamin expression, posttranslational modifications of lamins may further affect nuclear mechanics. Lamins are phosphorylated during mitosis, causing them to become soluble and disperse into the cytoplasm47,74. Because farnesylation and phosphorylation of lamins changes their solubility, interaction, and localization, these posttranslational modification may also offer cells a way to dynamically adjust their nuclear stiffness in response to mechanical stimuli.63

Lamin binding proteins

Beyond their direct structural role, lamins bind many different proteins, including transcriptional regulator, histones, and several inner nuclear membrane proteins (Fig. 2). Lamin binding partners include LBR, nesprins, SUN proteins, and members of the LEM-domain protein family, which comprises LAP2, Emerin, and MAN1 proteins.75,76 In the absence of lamins, many of the lamin binding proteins become mislocalized. This has severe consequences for force propagation across the nuclear envelope (see below) and mechanotransduction signaling. The LEM-domain proteins share a conserved ~40 amino acid sequence that allows them to bind BAF (Barrier to Autointegration Factor), a protein with roles in nuclear organization and DNA bridging.77,78 BAF helps to recruit lamin A and stabilize emerin at the nuclear envelope in addition to maintaining heterochromatin.79,80 The LEM-domain proteins have additional binding partners that could affect mechanotransduction signaling. Broadly, LAP2, emerin, and MAN1 all interact with GCL, a transcriptional repressor. Emerin is particularly interesting in this regard because it competitively binds BAF and GCL.81 Mutations in LEM domain proteins can cause changes in downstream BAF signaling, but can also disrupt additional signaling pathways such as TGF-β and Wnt signaling, as will be discussed in detail later.82,83

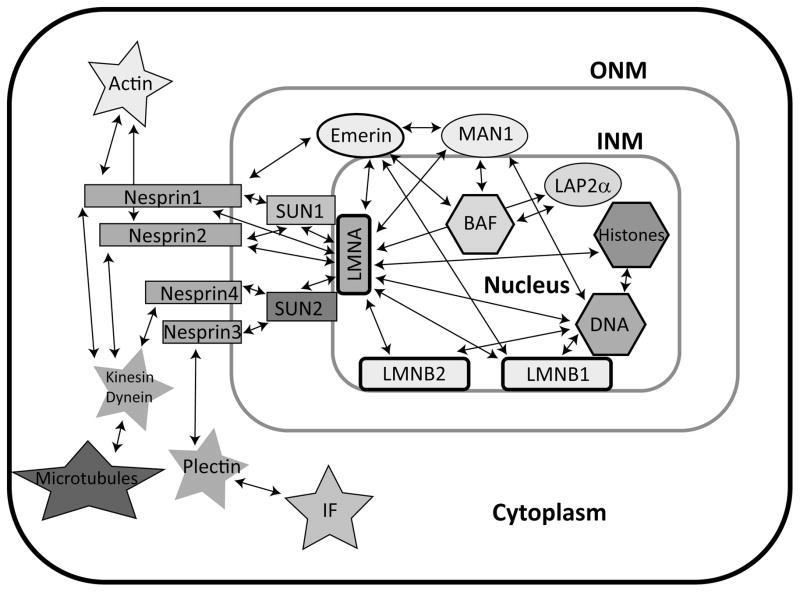

Figure 2. Nuclear envelope protein binding partners.

Lamins associate with numerous proteins/structures in the nuclear interior and the nuclear membranes, thereby modulating intracellular force propagation and mechanotransduction signaling. Many of the lamin binding proteins also bind to each other, creating a complex network of interactions. Red = cytoskeletal elements; orange = LINC complex proteins; purple = lamins; green = LEM domain proteins; blue = chromatin associated elements.

Lamins can also directly connect to the genome by binding DNA and histones.76,84 The areas of the genome that are bound to the nuclear lamina are called Lamina-Associated Domains (LADs) and are often transcriptionally repressed heterochromatin. In addition, lamins also directly bind to numerous transcriptional factors such as extracellular-signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), retinoblastoma protein pRb (RB1), Fos, sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 (SREBP1) and MOK2, among others.84–87 Of note is that phosphorylated Rb, one proposed regulator of lamin expression, can also directly bind lamins (together with LAP2α), suggesting a potential feedback loop. Some of these factors, such as ERK1/2 and c-Fos, have well established roles in mechanotransduction signaling and will be discussed in more detail later. For a detailed discussion of lamin binding partners and their function, we refer to a recent review by Simon and Wilson.10

Nuclear membranes and nuclear pore complexes

Adjacent to the nuclear lamina and forming a barrier to the surrounding cytoplasm are the inner nuclear membrane and the outer nuclear membrane. The latter is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a large intracellular membrane system. The space enclosed by the inner and outer nuclear membranes is the ≈30–50 nm wide luminal or perinuclear space. Proteins in the inner nuclear membrane can interact with, and be retained, by the underlying lamina and nuclear interior. In the absence of these interactions, as in the case of lamin A/C-deficient cells, the inner nuclear membrane proteins can diffuse into the outer nuclear membrane at the nuclear pores, where the membranes converge, and then further into the ER. Similarly, proteins in the outer nuclear membrane are often retained there by their interaction with inner nuclear membrane proteins and can be mislocalized to the ER if this interaction is lost.88 At least 74 membrane proteins specific to the nuclear envelope have been identified to date, conferring a variety of often tissue-specific functions from import and export, chromatin anchoring and regulation, and nucleo-cytoskeletal coupling.89,90

Nuclear pores help to regulate the active transport of large molecules (larger than ≈40 kDa) into and out of the nucleus. Ions and small molecules can passively diffuse through the membranes or the nuclear pores. Nuclear pore complexes are highly structured, symmetric channels that are regularly spaced along the nuclear envelope. This spatial regulation is likely due to interactions with the nuclear lamina, because loss of lamins can result in clustering of nuclear pore complexes.91 Nuclear pore complex components interact with a larger number of proteins at the nuclear envelope (e.g., lamins, SUN proteins) and the nuclear interior.92,93 Recent evidence suggests that proteins typically associated with the nuclear pore complex proteins can also be found deep inside the nuclear interior, where they may play a role in transcriptional regulation.11,12

LINC complexes

The lamina is connected to the cytoskeleton by the Linker of Nucleoskeleton and Cytoskeleton (LINC) complex, which spans both the inner and outer nuclear membrane to transmit forces across the nuclear envelope (Fig. 1). LINC complex consists of SUN proteins at the inner nuclear membrane and KASH-domain proteins at the outer nuclear membrane. The LINC complex proteins are highly conserved across organisms and their vertebrate names are a combination of the names originally given in C. elegans, D. melanogaster, and S. pombe. The SUN (Sad-1/UNC-84) proteins bind to the lamina and the SUN domain occupies the perinuclearspace. There are two SUN proteins in somatic cells, SUN1 and SUN2, which have distinct but overlapping functions.94 Three additional SUN proteins, SUN3–5, are only expressed in male germline cells.95 All SUN proteins are composed of an N-terminal nucleoplasmic domain, a transmembrane domain, and a luminal coiled-coil rod domain that ends in a trimeric, SUN-domain head.96 The main difference between SUN1 and -2 and the germline SUN proteins is the length of the rod domain.96

The trimeric C-terminal of the SUN proteins binds up to three KASH (Klarsicht/ANC-1/Syne homology) peptides, which make up the luminal C-terminus (and the transmembrane domain) of the aptly named KASH-domain proteins. The first four KASH-domain family members are referred to as nesprins (nuclear envelope spectrin repeat proteins), each consisting of several isoforms resulting from alternative splicing or initiation.97 Historically, nesprin-1 and -2 were named Enaptin and NUANCE, respectively. Some nesprins were also referred to as SYNEs (synaptic nuclear envelope proteins), because of their presence in myonuclei at neuromuscular junctions.98 A fifth family member, KASH5, is germ cell specific and lacks the name-sake spectrin repeats of nesprins.99 Nesprins-1, -2, and -3 are generally widely expressed, and at least one nesprin isoform is found in all cell-types.100 In contrast, nesprin-4 expression is specific to secretory epithelial cells. On the cytoplasmic side, nesprins can interact with all major cytoskeletal structures. The largest isoforms of nesprin-1 and -2 directly bind to actin and nesprins-1 and -2 also bind to kinesin and dynein; nesprin-3 engages intermediate filaments via plectin; nesprin-4 connects to the microtubule network via kinesin-1 (Fig 1).101–104 The large, “giant”, nesprin isoforms are found on the outer nuclear membrane, while smaller nesprin isoforms like nesprin-1α and nesprin-2β also localize to the inner nuclear membrane and bind lamins.103,105,106

The integrity of the LINC complex and cytoskeletal filaments is needed to support intracellular force transmission to the nucleus. LINC complex disruption causes changes in both the nuclear and cytoskeletal morphology, including loss of the actin and vimentin network surrounding the nucleus.107,108 Depletion of LINC complex components, or expression of dominant negative nesprin constructs, results in altered nuclear cross-sectional area and an increase in nuclear height. This is presumably due to loss of cytoskeletal tension or compression acting on the nucleus.109 In additional to changes in nuclear morphology, down regulation of nesprin-1 also increases focal adhesion strength, potentially in an attempt to balance the forces normally distributed to the nucleus. In addition to these findings, many other groups have demonstrated the effect of the LINC complex on nuclear morphology based on substrate stiffness, 2-D versus 3-D microenvironment, and under strain.110–114

In many ways, the LINC complexes appear analogous to the focal adhesion complexes at the plasma membrane, which help transmit forces from the cellular environment to the cytoskeleton and are also involved in mechanosensing.115 Comparing the current view of the simple LINC complex structure with the complex structure and interaction of focal adhesion complexes and the many associated proteins, it becomes apparent that there is still much work that needs to done to better understand nucleo-cytoskeletal coupling. As of now, there are a few other proteins that are known to help control the interaction between nesprins and SUN-proteins. Samp1 was recently identified as a LINC complex-associated protein that interacts with SUN1 and aids in nuclear positioning.116,117 Torsin-A appears to be another potential regulator of SUN-nesprin interaction,118 but much remains to be uncovered about how binding between SUN-proteins and nesprins is controlled. Furthermore, there are still many questions regarding the formation, maintenance, and regulation of LINC complexes, especially in response to mechanical stimuli. For example, does the same principle of concurrent inside-out and outside-in signaling that governs cell adhesion also apply to the LINC complex? And which other proteins could be involved in such regulation or potential mechanosensing?

Mechanically induced changes in nuclear structure

While the above section paints a picture of the static nuclear structure, mechanosensing and mechanotransduction are active processes. It is now well established that forces from the extracellular environment and the cytoskeleton are transmitted to the nucleus, where they can result in (intranuclear) deformations. Physiologically, such forces can result from fluid shear stress, tissue compression, cell migration and tissue strain. Cell generated traction forces, responding to the stiffness of the underlying substrate, also affects nuclear morphology. To probe specific interactions and intracellular force transmission, more targeted, but also more invasive, experimental techniques have been developed and applied to a variety of cellular systems (Fig 3). These experiments firmly illustrate how the nuclear structure and morphology reflects changes in the extracellular and intracellular mechanical environment, and how changing the structure and composition of the nuclear envelope can significantly affect the intracellular force propagation.

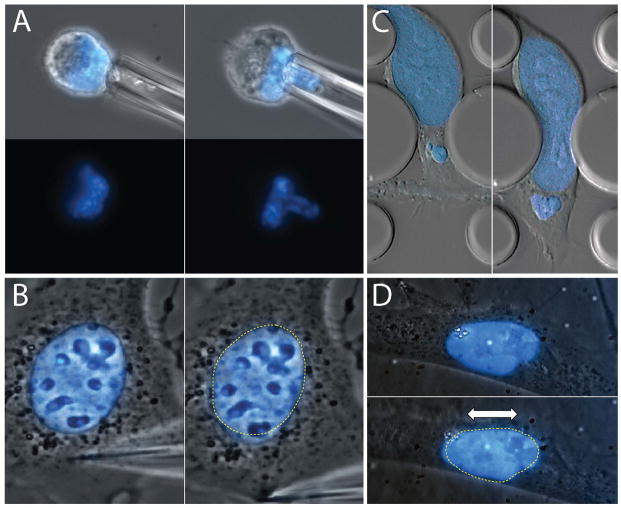

Figure 3. Mechanically induced formation of the nucleus.

Examples of biophysical assays to probe nuclear mechanics and nucleo-cytoskeletal coupling. Images show overlay of phase contrast images with fluorescent signal (blue) from Hoechst 33342 labeled nuclei. A) Micropipette aspiration assay to probe nuclear deformability. Images of mouse embryo fibroblast with fluorescently labeled nuclei before (left) and during (right) micropipette aspiration. Bottom: Corresponding fluorescence images alone, illustrating large nuclear deformation during aspiration into the micropipette tip. B) Microneedle manipulation of a mouse embryo fibroblast to assess force transmission between the cytoskeleton and nucleus. A microneedle is inserted into the cytoplasm and moved away from the nucleus, resulting in large nuclear deformations. Left, initial position; right, induced nuclear and cytoskeletal deformation after microneedle movement. Dotted line indicates initial nuclear outline. C) Migration of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell through microfluidic constrictions channels. The nucleus must undergo substantial deformation as the cell passes through the ≈3 μm × 5 μm opening. Left, nucleus before entering constriction; right, nucleus inside the constriction. D) Nuclear deformation of human skin fibroblast subjected to ≈20% uniaxial substrate strain. Top, cell before strain application; bottom, cell and nuclear deformation during strain application. Dotted line indicates nuclear outline before strain application.

Nuclear deformation during cell migration

As previously discussed, the nucleus is the largest organelle and resists deformation more than the surrounding cytoplasm. Because of this, the rate of nuclear deformation may constitute a limiting factor in cell migration through narrow constrictions.15,19,119 In cells migrating through dense collagen matrices, large nuclear deformations and protrusions can be observed as the cell/nucleus squeezes through openings as small as ≈3 μm in diameter19,72. The limit of nuclear compressibility appears to be ≈10% of the initial nuclear diameter as migration halts when trying to navigate smaller constrictions.19 Some specialized cells, such as neutrophils, may have evolved highly lobulated nucleui with very low levels of lamins to mitigate this limitation15. Ongoing research is aimed at further establishing the role of nuclear mechanics in 3-D cell migration, including the contributions of lamin levels, which are altered in many cancers. However, changes in the nuclear envelope composition not only affect nuclear deformability, but can also disrupt force transmission between the nucleus and cytoskeleton (and possibly signaling pathways). This manifests in decreased overall cell migration speeds and lack of persistence in lamin A/C-null and –mutant cells.112,120. Nuclear deformation and positioning has been extensively studied on cells migrating on 2-D substrates, particularly in response to stiffness. At the nuclear envelope, protein arrays consisting of SUN2 and nesprin-2G bind dorsal actin cables to form so called transmembrane actin-associated nuclear (TAN) lines, which allows the cell to use retrograde actin flow to reposition the nucleus for migration.121 Highlighting the importance of intact connections between the cytoskeleton and the nucleus, depleting either lamins, emerin, nesprin-1, nesprin-2, nesprin-3, SUN, or plectin all result in an increased distance between the nucleus and the centrosome, along with inhibited cell polarization and migration.120,122–125

Nuclear deformation under shear stress

Vascular endothelial cells experience constant fluid shear stress. This consistent force results in the alignment of cells in the flow direction.22,126 Importantly, fluid shear stress application for 24 hours also causes endothelial cell nuclei to flatten, lengthen, and increase up to 50% in stiffness.127 What is fascinating is that these changes persist even after nuclei are isolated, suggesting that stable nuclear reorganization or remodeling occurred.127 Some of these changes may be facilitated by reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton, as related to the magnitude of shear stress. The cytoskeletal reorganization and resulting irreversible deformations require the presence of nesprins-2 and/or -3, highlighting again the importance of LINC complexes.123,128 Beyond the gross nuclear level, shear stress application also affects subnuclear structures; after a half hour of force application, rDNA upstream of polymerase I showed directionally enhanced diffusion, on the same time scale as cytoskeletal remodeling.129

Nuclear deformation under compression

Cells of mesenchymal origin frequently experience compressive forces, for example, in cartilage and during muscle contraction. Compression of chondrocytes results in large changes in nuclear shape and height (but not volume);130 associated changes in cellular osmolarity could further affect nuclear structure and chromatin organization.131 In response to compressive forces, mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking lamin A/C deform isotropically, while wild-type cells exhibit anisotropic deformations.132 Because isolated nuclei deform isotropically, it is hypothesized that the anisotropic deformation observed in the wild-type cells is due to cytoskeleton linkages, which are disrupted in the lamin A/C-deficient cells. Importantly, lamin A/C-deficient cells show less resistance to compression and more frequent nuclear rupture133, again illustrating the importance of A-type lamins in stabilizing the nucleus.

Nuclear deformation under strain application

In cells subjected to strain, e.g., by stretching the underlying substrate or an entire tissue, the nucleus undergoes substantial deformations. In human and mouse embryo fibroblasts plated on flexible silicone membrane, nuclear deformation accounts for up to 30% of the applied membrane strain, with depletion of lamins A/C resulting in significant increases in nuclear strain.62,65 Similar results can be observed in intact muscle tissue subjected to uniaxial stretch.53 Elongated and fragmented nuclei have been observed in muscle tissues of lamin A/C-deficient mice and in patients with lamin A/C and emerin mutations suggesting that the mechanical stress experienced in muscle cells can cause dramatic changes and defects in nuclear structure53,62,106. Importantly, disruption of the LINC complex using dominant negative nesprin or SUN-protein mutations or nesprin knock down/out can almost completely abolish strain-induced nuclear deformation or alignment,108,109,113 stressing the importance of intact nucleo-cytoskeletal coupling to transmit forces from the cytoskeleton to the nucleus.

Substrate stiffness and patterning

Cells fine tune their cytoskeletal tension to match the stiffness of the underlying substrate, a process which may have a profound effect on the forces experienced by the nucleus. On stiffer substrates, the nucleus flattens due to increased actomyosin-generated contractile forces that are transmitted to the nucleus via the LINC complex.110 In lamin A/C-mutant cells, growing the cells on softer hydrogels can help minimize nuclear rupture and distortion by reducing the forces acting on the nucleus.111 The cellular details by which the actin cytoskeleton dictates changes in nuclear shape is still incompletely understood, with competing ideas of whether apical actin cables or basal actin stress fibers have a stronger influence on nuclear morphology.111,134 Substrate patterning also effects cell spreading and the cytoskeletal organization.

Micromanipulation

Before the implementation of powerful micromanipulation tools, such as microneedle manipulation,135 it was unknown whether forces at the cell membrane could lead to subnuclear remodeling. By harpooning cells with a glass microneedle and exerting a pulling force on their cytoskeleton or on beads attached to the plasma membrane, Maniotis et al.135 demonstrated the structural coupling between the cell surface and the nucleus via the actin cytoskeleton. Using a refined version of the technique coupled with detailed nuclear and cytoskeletal displacement mapping, Lombardi and colleagues proved that an intact LINC complex is required for this intracellular force transmission.93

Potential mechanisms for direct nuclear mechanosensing

The way the nucleus mechanically responds to various physical stimuli has been well characterized (see above section), yet few studies have provided molecular details directly linking force-induced deformations to specific transcriptional changes. Thus, we return to our original question: can the nucleus act as a mechanosenor? So far, the pursuit within the field of mechanobiology to identify force transducers has primarily focused on stretch-activated ion channels, cell adhesion complexes, and the cortical cytoskeleton. Nonetheless, a number of exciting recent findings have called attention to the nuclear interior and nuclear envelope as potential sites of cellular mechanosensing.

Distinguishing the exclusive role of the nucleus in mechanosensing can be difficult given the myriad of biochemical signals originating from the cytoplasm that are processed in the nucleus. Researchers have been applying two alternative approaches to address this problem, each with its own advantages and limitations. One way to overcome this challenge is by experimenting on isolated nuclei, which allows direct control over the forces exerted on the nucleus and eliminates confounding effects from cytoplasmic signaling, but may not accurately recapitulate the physiological forces and biochemical environment of the nucleus in living cells. The other approach is to conduct experiments on intact cells at high temporal resolution, with the assumption that mechanical forces are transmitted significantly faster (milliseconds vs. seconds and minutes) to the nucleus than biochemical signals,8 so that the earliest observed changes represent direct forced-induced events in the nucleus rather than downstream responses to cytoplasmic signals.

Following the former experimental approach, Swift et al.63 employed a cysteine-shotgun mass spectrometry approach (CS-MS) to assess structural changes in isolated nuclei exposed to controlled shear stress. In CS-MS, fluorescently or otherwise labeled tags can bind to cryptic cysteine residues that are buried deep within the protein structure and become exposed when the protein partially unfolds under the applied force. The CS-MS technique is a high throughput means to characterize and quantify the modifications (e.g. phosphorylation) of endogenous proteins by comparing their mass-to-charge ratios under different conditions. The CS-MS shear rheometer assay identified a cryptic site (Cys522) in the Ig-domain of lamin A that is responsive to shear stress on the order of 1 Pa. This structural change might alter the association of the Ig-domain with its interaction partners, which include actin, DNA, LAP2α and nesprin-2,38, thus acting as a molecular mechanosensor. In an attempt to recapitulate the Ig-domain unfolding in living cells, mesenchymal stem cells were grown on substrates of varying stiffness, which induces increasing cytoskeletal tension, and then analyzed by CS-MS. However, under these conditions, there was no evidence of Cys522 exposure suggesting that intracellular forces were either too weak to induce unfolding of the Ig-domain under physiological conditions, or that the cells adapted to the altered mechanical environment by strengthening the nuclear lamina and preventing protein unfolding.63 Interestingly, cells grown on stiffer substrates showed reduced phosphorylation and altered nuclear distribution of lamin;63 however, the underlying molecular mechanism and whether this phenomenon can be directly induced mechanically remain unclear.

Another recent report of direct nuclear mechanosensing probed deeper into the heart of the nucleus to study nuclear body dynamics in response to oscillatory stress exerted at the cell membrane. Wang and colleagues31 measured fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) ratio changes between two fluorescently-conjugated cajal body (CB) proteins as an indicator of physical association between the two proteins. Force application beyond a physiologically relevant stress threshold caused rapid and irreversible dissociation between SMN and coilin within the CB of HeLa nuclei.31 The effect required an intact F-actin–LINC complex–lamin A/C network and was sensitive to changes in substrate stiffness, suggesting that a certain cytoskeletal tension is required to transmit forces to the nucleus and induce nuclear deformations.111 As the observed changes occurred rapidly (< 1 second), the SMN-coilin dissociation was proposed to occur independent of intermediate biochemical cascades. Since CBs interact directly with chromatin, the findings support the idea that force induced dissociation of nuclear proteins can alter gene expression, but follow-up studies will be required to detect functional consequences and whether long-term transcriptional changes occur.

Following a similar strategy, Iyer et al. visualized force-induced changes in chromatin structure in HeLa cells subjected to mechanical forces via magnetic particles on the plasma membrane136. They observed a decrease in the anisotropy of the fluorescence signal of GFP-labeled histone, interpreted as chromatin decondensation, that occurred on the order of seconds, followed by slower changes in the nuclear cross-sectional area (tens of seconds) and translocation of the transcription factor MKL1 to the nucleus (minutes).

Further evidence for mechanically induced changes in the nuclear interior was provided by the Dahl group, which studied nuclear body dynamics in the context of shear and compression forces. Using fluorescent-tagged upstream binding factor-1 (UBF-1) and fibrillarin to track subnuclear movements, they discovered force magnitude- and duration-dependent changes in UBF1-GFP and fibrillarin-GFP displacement.129 While the increased subnuclear movement could be indicative of mechanically induced genome reorganization, the fact that many of the changes only occurred after 30 minutes does not exclude the possibility that these changes primarily reflect a response to cytoskeletal reorganization, prompting further investigation.

Although the above findings support a direct mechanism whereby chromatin and other subnuclear structures can sense and respond to mechanical forces exerted at the cell membrane, another recent study makes it clear that nuclear deformation is not required for cellular mechanotransduction. Using dominant negative nesprin and SUN-protein constructs to disrupt force transmission between the cytoskeleton and the nucleus, Lombardi and colleagues found that despite abolishing mechanically induced nuclear deformation, expression of the mechanosensitive genes Egr-1, Iex-1, Pai-1, and vinculin was indistinguishable from control cells.108 These findings suggest that at least for the investigated genes, alternative mechanosensing mechanisms in the cytoplasm that are then biochemically transmitted to the nucleus may be sufficient for transcriptional activation.

Mechanotransduction signaling in the nucleus

When force is exerted on a cell, it is propagated through the various intracellular structural scaffolds. Along the way, the force causes mechanosensitive proteins to change conformation, resulting in exposure of cryptic binding sites, phosphorylation of specific residues, and/or altered binding affinities and interaction partners. Ultimately, many of the mechanically induced signaling pathways converge on the nucleus and involve the import/export of transcription factors, their interaction with co-factors, and changes in chromatin organization (Fig 4.).137 Recent findings suggest that many of the involved pathways directly or indirectly interact with nuclear (envelope) proteins, as discussed in detail below. Consequently, the role of the nucleus in mechanotransduction is not limited to direct mechanosensing; it also includes the modulation of biochemical signals arriving at the nucleus.

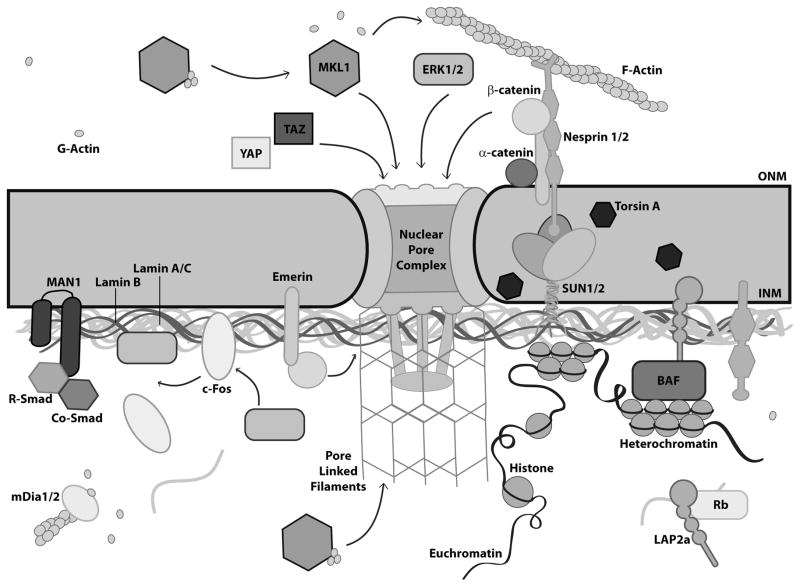

Figure 4. Nuclear envelope connectivity and signaling.

Schematic overview of signaling pathways (MLK1/SRF, MAPK and ERK1/2, YAP/TAZ, TGF-β, and Wnt) associated with nuclear envelope proteins.

MAPK/ERK/Fos

One of the most prevalent and best characterized responses to mechanical stress is the phosphorylation of proteins, which leads to changes in their binding affinities and often triggers further downstream signaling. The mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway mediates cellular reactions to stress and growth factors by regulating differentiation, apoptosis and inflammation.138 There are multiple distinct MAP kinases, including ERK1/2, p38, JNK, and ERK3-5. The first three constitute particularly important branches of the MAPK pathway in cellular mechanotransduction.2 Intriguingly, recent findings have implicated lamins A/C and emerin in causing impaired MAPK signaling resulting in cardiac and skeletal muscle disease. Patient samples carrying different LMNA mutations responsible for dilated cardiomyopathy have an increase in phosphorylated ERK and JNK in the nucleus.139. Cardiomyocytes from mouse models that have either a lamin A/C mutation (Lmna H222P) or lack emerin also have enhanced ERK1/2 signaling.140,141 Surprisingly, emerin and lamin mutations appear to have somewhat different effects. While the Lmna H222P mutation affects the JNK branch, loss of emerin does not.89,90 Both, however, have similar effects on the ERK1/2 branch. In addition, p38 phosphorylation is shown to be increased in cardiac tissue samples from laminopathy patients142,143 Lastly, lamin A/C- and emerin-deficient fibroblasts subjected to cyclic strain respond with decreased expression of the mechanosensitive genes egr-1 and iex-1, which are downstream targets of the MAPK pathway.62,144

At least some of the effects of lamin mutations on MAPK signaling may be attributed to the direct interaction of lamin A/C with c-Fos; when ERK1/2 enters the nucleus, it displace c-Fos by binding to lamins and becomes transcriptionally active (Fig. 4).145 Although this mechanism had not been definitively confirmed, there are multiple reports supporting it. For instance, cells with mutated lamins have normal activation of ERK1/2 in the cytoplasm but decreased expression of downstream genes.62,146,147

Wnt signaling

Wnt signaling is important for multiple developmental processes such as axis patterning, as well as differentiation, proliferation and migration.148 Wnt has been shown to be modulated by mechanical forces in bone cell differentiation.149 There are three Wnt pathways, the canonical Wnt pathway, which involves translocation of the transcriptional co-activator β-catenin from the cytoplasm and cell-cell adhesions to the nucleus, and two non-canonical pathways. Importantly, β-catenins can directly interact with several nuclear envelope proteins. At the nuclear envelope, emerin is responsible for nuclear export of β-catenin, so cells lacking emerin or lamins A/C show enhanced growth and proliferation due to β-catenin accumulation in the nucleus (Fig 4.).83 Furthermore, nesprin-2 can interact with α-catenin, together with emerin and β-catenin.150 Recently, it has been proposed that nesprin-2, α-catenin, emerin and β-catenin form a complex that recruits β-catenin to the perinuclear region and facilitates its nuclear import, as β-catenin lacks a nuclear localization sequence.151 This mechanism could explain why depletion of nesprin-2 reduces levels of nucleoplasmic β-catenin150. Other potential effects of altered Wnt signaling include impaired fibronectin and Col11A1 synthesis, which could affect cellular mechanosensing at the plasma membrane152.

TGF-β and Smad signaling

Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) stimulates cell proliferation, extracellular matrix synthesis and degradation, as well as aspects of embryogenesis and wound healing.151,153 TGF-β expression levels have been shown to directly correlate with mechanical loading in tendons and to be activated downstream of integrin-mediated contraction in myofibroblasts.154,155 Binding of TGF-β to its receptor on the plasma membrane induces formation of a receptor ligand complex and activation of the cytoplasmic receptor kinase domain, which results in phosphorylation of Smads, transcription factors that translocate from the cytoplasm into the nucleus, where they activate transcription of TGF-β target genes. There are three different kinds of Smads; regulating Smads (R-Smads), Co-Smads, and inhibitory Smads. The nuclear envelope LEM domain protein MAN1 binds R-smads in a manner that also regulates BMP and activin signaling in addition to TGF-β.156 R-Smads bound to Co-Smads are transcriptionally active and enter the nucleus. MAN1 breaks this complex apart by selectively binding to R-Smads, promoting nuclear export of the Smads and resulting in attenuation of TGF-β signaling (Fig 4.).157 In addition to MAN1, lamin A/C regulates TGF-β signaling by modulating the phosphorylation of Smads in a mechanism that involves lamin-bound PP2, a nuclear phosphatase.158,159 The role of lamins A/C and emerin in modulating Smad activity may be particularly relevant for muscle tissue, because TGF-β1 stimulates satellite cell differentiation. Disruption of this pathway by lamin or emerin mutation may contribute to impaired muscle regeneration.

MKL1/SRF Signaling

The serum response factor (SRF) transcription factor and its co-factor, megakaryocytic acute leukemia (MKL1, also known as MAL or myocardin-related transcription factor-A (MRTF-A)), control a large number of genes involved in growth factor response, cytoskeletal remodeling (e.g., vinculin, actin, and actin binding proteins), and muscle-specific functions such as myoblast fusion and differentiation.160 The MKL1/SRF pathway is highly sensitive to changes in actin dynamics.161 MKL1 is normally sequestered in the cytoplasm through interactions with G-actin’s three RPEL motifs. This prevents importin dimers from binding with a bipartite NLS signal in the regulatory domain of MKL1.160,162 Serum- or mechanically induced polymerization of actin releases G-actin from MKL1 and allows the translocation of MKL1 to the nucleus, where it, together with SRF, activates SRF/MKL1 target genes (Fig 4). Recent studies illustrate the importance of this pathway in diseases affecting mechanically-stressed tissues, particularly cardiac and skeletal muscle. For example, MKL regulates the fibrotic repair gene program in injured cardiac tissue following myocardial infarction,163 and SRF-null mice develop severe cardiac defects213.

A recent study revealed a novel mechanism by which nuclear envelope proteins can affect actin dynamics and MKL1/SRF signaling.164 Lamin A/C mutations are shown to displace emerin from the inner nuclear membrane, thereby leading to disturbed actin polymerization and impaired nuclear import and increased nuclear export of MKL1. This causes decreased nuclear localization of MKL1 and reduced expression of MKL1/target genes in vitro and in vivo.164 This effect was attributed to the ability of emerin to bind and polymerize actin,165 but it remains unclear to what extent emerin at the inner nuclear membrane and its effect on nuclear actin, versus emerin on the outer nuclear membrane and its effect on cytoskeletal actin166 contributes to this mechanism.

Taken together, these findings shine a growing spotlight on the largely uncharted territory of nuclear actin structure and function. A recent study demonstrated the ability of the formins mDia1 and mDia2 to drive nuclear actin polymerization and to induce MKL1/SRF activity.167 While formins were previously known to aid actin filament assembly in the cytoplasm, this study first documented a role of formins in the nucleus, suggesting that formins (and emerin) could play an important role in controlling nuclear actin polymerization and in modulating MKL1/SRF activity. Considering the complex feedback loop whereby changes in actin dynamics and activation of MKL1/SRF signaling results in increased expression of SRF, actin, and actin-modulating proteins, it becomes challenging to conclude whether cytoplasmic events drive nuclear signaling or the other way around. Furthermore, several other signaling pathways converge with MKL1/SRF signaling. For example, Smad3 can bind MKL1 and prevent it from binding to SRF. On the other hand, β-catenin binds both Smad3 and MKL1, but without disrupting the MKL1/SRF complex.168 Regardless of the many remaining questions, the SRF pathway has already immerged as an important signaling pathway linking nuclear and cytoskeletal structure with gene regulation. Disturbed MKL1/SRF signaling may in part explain the altered mechano-sensitivity as well as the tissue-specific phenotypes in diseases caused by mutations in lamins A/C and emerin.

YAP/TAZ signaling

Recent findings indicate that the YAP/TAZ pathway, traditionally considered to be a component of the Hippo pathway, can operate independently to mediate the cellular response to mechanical cues.169,170 YAP/TAZ activation is particularly sensitive to substrate stiffness and cytoskeletal tension, resulting in an increased presence of YAP/TAZ in the nucleus when cells are grown on stiffer substrates that promote cell spreading.169,170 Unlike the SRF pathway discussed above, YAP/TAZ shows nuclear accumulation in response to cell spreading, whereas SRF shows a decrease in activity169. In addition, SRF is responsive to F-/G-actin ratios, but this metric has no effect on YAP/TAZ activity. While lamin A/C overexpression decreases YAP1 levels and nuclear localization, the exact interplay between lamins and YAP/TAZ signaling remains unresolved. Interestingly, expression of YAP1 and its binding partners did not scale with the stiffness of the corresponding tissue63.

Interaction of Retinoblastoma protein, lamins A/C and LAP2α

Retinoblastoma protein (Rb) is part of the E2F pathway and helps to regulate cell cycle progression and differentiation.171 Nuclear accumulation of Rb is present in proliferating cells. LAP2α and lamin A/C bind to RB and halt cell cycle progression; when LAP2α is depleted, cells continue to proliferate, preventing differentiation of stem cells.172,173 Similarly, lamin A/C has been shown to play a role in cell cycle regulation; lamin A/C null cells show decreased proliferation with impacts in tissue regeneration.174 This defect is rescued by LAP2α knockdown.174 Recently, Rb has been proposed to act as a potential regulator of lamin expression levels, but the mechanistic details remain to be determined.63

Phosphorylation of nuclear envelope proteins

In addition to modulating localization and activity of many transcriptional regulators, several nuclear envelope proteins themselves may be substrates of signaling pathways. Emerin has at least six known phosphorylation sites, four of which are regulated by the Src, Abl, and Her2 kinases, which in turn regulate emerin’s ability to bind BAF.175,176 The Her2 pathway is particularly interesting, as it has important implications for breast cancer and cardiac muscle function. Approximately a quarter of human breast tumors have up-regulated Her2 expression,177 but the role of emerin signaling has yet to be studied. Illustrating the role of Her signaling on muscle function, mice without Her2 develop cardiomyopathy and other symptoms such as lack of coordination and muscle wasting similar to muscular dystrophies.175 Lmo7, another emerin-interacting protein, can regulate breast cancer cell migration by modulating GTPase/RhoA activity.178 Lmo7 shuttles between focal adhesions and the nuclear envelope, where emerin binding inhibits its activity.178 At the focal adhesions, Lmo7 specifically binds to p130Cas, a known mechanosensitive protein.179 Of note, emerin also interacts with proteins in the MAPK and Wnt pathways. With so many interactions, one question that emerges is how emerin regulates its myriad of binding partners. It has been hypothesized that emerin exists in multiple types of protein complexes at once, allowing it to have a designated complex for various signaling pathways; many of these interactions may be regulated by emerin phosphorylation.180 Other LEM domain proteins similarly show altered interaction upon phosphorylation. In MAN1, phosphorylation of three different residues interrupts binding to BAF;137,181 changing the phosphorylation state of LAP2α affects its binding to chromatin but not to the nuclear envelope.182 For lamins and other nuclear envelope proteins, which can also undergo various posttranslational modifications, the functional consequences and prevalence of such modifications outside of their role in mitosis are only beginning to emerge and are likely to produce exciting new insights.10,63

Functional consequences of impaired mechanotransduction and disease

As illustrated by the above sections, proper mechanosensing and mechanotransduction signaling is essential for numerous cellular functions. Both the external mechanical input, as well as the integrity of the internal connectivity, can affect nuclear morphology, mechanosensing, and transcription. Mutations in nuclear envelope proteins and disturbed expression of nuclear proteins can thus have severe functional consequences, resulting in a variety of human diseases. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how mechanical forces affect the cell, both the structurally and by rerouting its signaling pathways. This is especially true for mechanically active tissue such as skeletal and cardiac muscle which is primarily affected in many of the pathologies resulting from defects in nuclear (envelope) proteins. Beyond the immediate effects of disturbed protein function, the mechanical microenvironment is implicated in several other diseases, such as cancer, where changes in the mechanical environment are thought to contribute to the disease progression, or vascular disease, where plaques often form at sites of perturbed fluid shear stress.2 An improved understanding of the underlying disease mechanisms is critical for developing therapeutic approaches. In particular, it is important to distinguish which of the following scenarios constitutes the primary disease driver: (1) changes in the mechanical environment, in which cellular mechanotransduction signaling functions normally but responds to an altered input; (2) physical defects in cellular structure, resulting in altered force transmission, mechanosensing, and/or direct physical damage in response to mechanical stress; or (3) altered mechanotransduction signaling. Only the third scenario is readily amenable to pharmaceutical intervention with small molecules to restore normal signaling.

In the following, we highlight some of the diseases that can be caused by mutations in nuclear envelope proteins such as lamins A/C and emerin as examples of how defects in nuclear envelope proteins can affect cellular mechanics and mechanotransduction. What is particularly perplexing about the large number of diseases resulting from mutations in nuclear envelope proteins is that although the implicated proteins are almost ubiquitously expressed throughout the body, many of the diseases primarily affect skeletal and cardiac muscle and tendons. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain these tissue-specific effects. One hypothesis is the ‘structural hypothesis’ – loss of protein function causes nuclear fragility, rupture and death. This mechanism helps to explain the progressive nature of many of the laminopathies, especially in mechanically stressed tissues. Another hypothesis is that of disturbed gene regulation – mutations in nuclear envelope proteins affect their (tissue-specific) binding partners and lead to altered gene expression. Another, related hypothesis is that the mutations alter the ability for stem cells to differentiate and decrease their self-renewal capacity, thereby causing defects in the maintenance and repair of tissues.183 Importantly, these hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, and the specific disease mechanism probably lies at an intersection of these propositions.

Muscular Dystrophy

The discovery that mutations in the nuclear envelope protein emerin cause Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy was one of the main motivators for studying nuclear structure and mechanics.184 To date, the nuclear envelope proteins lamin A/C, emerin, nesprin1/2, and SUN1 have all been linked to Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy.5,106,184 Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy presents with early contractures, humero-peroneal weakness, and cardiac conduction defects, although overall the disease is less severe than Duchenne muscular dystrophy, which is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene.185 Muscle biopsies from patients with Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy often show highly fragmented nuclei83. Another signature of muscular dystrophy is the mislocalization of the nucleus in muscle fibers, with cells lacking lamins or nesprins showing loss of myonuclei from the neuromuscular junction, suggestive of defects in anchoring of the nucleus to the cytoskeleton.175,186,187 Impaired nucleo-cytoskeletal coupling and disrupted force transmission between the cytoskeleton and nucleus has also been reported in fibroblasts expressing lamin A/C mutations responsible for muscular dystrophies.53,188 A detailed analysis comparing a large set of lamin A/C mutations found that mutations that cause striated muscle disease often lead to impaired lamin assembly, reduced nuclear stability, and impaired nucleo-cytoskeletal coupling, while mutations that cause familial partial lipodystrophy have no effect on nuclear stability.53 Importantly, cells lacking lamins A/C or emerin have severe defects in several mechanotransduction pathways in vitro and in vivo, including failure to adequately activate expression of the mechanosensitive genes Egr-1 and Iex-162,65,189 and in the translocation of MKL1 to the nucleus.164,165 However, it remains to be established whether the defects in mechanotransduction signaling are caused by altered nuclear mechanics and impaired force transmission to the nucleus or primarily represent disturbed interactions between lamins/emerin and binding partners involved in transcriptional regulation. Regardless of the mechanism, the impaired mechanotransduction signaling may not only weaken muscle adaptation to mechanical stress189 but could also affect appropriate stem cell differentiation, as lineage commitment is strongly modulated by cells sensing their mechanical environment190.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

While dilated cardiomyopathy is often associated with muscular dystrophy, some lamin A/C mutations also cause cardiomyopathies without affecting skeletal muscle.3 Dilated cardiomyopathy is characterized by progressive weakening of the heart muscles, thinning of the left ventricle wall, and insufficient pumping that typically leads to heart failure.191 Dilated cardiomyopathy is the most prevalent disease caused by mutations in LMNA but can also be caused by mutations in emerin, nesprin-1 and -2, LUMA, an inner nuclear membrane protein that binds emerin, and LAP2α.3,192 Many of the disease mechanisms may mirror those for muscular dystrophy described above, and it remains unclear why/how some mutations specifically affect cardiac but not skeletal muscle. Possible explanations include cell-type specific differences in (mechanotransduction) signaling pathways or the fact that skeletal muscle has a higher potential for repair and regeneration compared to cardiac tissue. Recently, animal studies have produced promising evidence that blocking hyperactive MAPK signaling can significantly delaying the development of cardiomyopathy and prolong survival in mice expressing lamin or emerin mutations.142,143,193–195

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is a premature aging disease that results from the build-up of progerin, a mutant form of lamin A with a 50 amino acid deletion in the tail domain that leads to permanent farnesylation and membrane accumulation.196 Children with HGPS appear normal at birth, but soon begin to present with stunted growth, thinned skin, hair loss, atherosclerosis and cardiac defects; patients typically die from heart attacks and strokes in their early teens.197,198 HGPS cells have stiffer nuclei and are more prone to mechanically induced damage when stretched or squeezed through narrow constrictions.129,199,200 In addition to increased sensitivity to mechanical stress, cells from HGPS patients display impaired proliferation in response to strain, altered extracellular matrix synthesis, and disturbed Wnt signaling, which may provide a mechanism explaining the predominance of vascular disease in HGPS.152,199 Currently, clinical trials aimed at blocking accumulation of progerin at the nuclear envelope by treatment with farnesylatransferase inhibitors, statins, and bisphosphonates are ongoing and have provided some encouraging findings, but it remains to be seen whether the beneficial results can be attributed to the drugs’ effects on lamin farnesylation or other molecular targets.201

Open questions and future research directions

Moving forward, there are several key areas that need to be addressed regarding the role of the nucleus in mechanotransduction. First, a more thorough understanding of the proteins involved in LINC complexes is needed to better understand intracellular force transmission. Further work is needed in identifying LINC-complex associated proteins as well as in determining interaction partners with structural and signaling molecules at the nuclear envelope. For example, how is the SUN/nesprin interaction dynamically regulated to allow controlled engagement of nucleo-cytoskeletal connections without ‘locking up’ the nucleus? The recent discoveries of Samp1 and Torsin A as potential mediators116,118 are likely just the tip of the iceberg. Considering that close to 100 unique nuclear membrane proteins have been identified to date and only a minuscule subset of these proteins have been functionally characterized, it is likely that additional proteins contribute to mechanical coupling and/or signal processing at the nuclear envelope.202 Combining this research with CS-MS, which labels mechanically sensitive cysteine residues in proteins, will have the potential to reveal novel nuclear mechanosensitive proteins. A better understanding of the mechanical coupling between the nucleus and the cytoskeleton may also explain which cytoskeletal structures and connections are primarily responsible for mediating nuclear shape and morphology, for example, during cell migration or when cells are subjected to mechanical force or grown on substrates with varying shapes or stiffness.

The elephant in the room, and probably one of the biggest questions in mechanobiology, is whether mechanically induced nuclear deformations alone can result in a consistent, dose responsive change in gene expression, i.e., whether the nucleus (or part of it) can serve as a cellular mechanosensor. To answer this question, single cell assays will be useful in matching precise measurements of (sub-)nuclear deformation with reliable readouts for mechanically induced gene expression. These may include both DNA and RNA FISH technologies to assess intranuclear localization of specific genes and could be complemented by emerging technologies to visualize transcriptional activity in living cells.9 To avoid confounding factors from cytoplasmic mechanotransduction signals, these experiments should be complemented by assays involving isolated nuclei subjected to mechanical stimulation. However, finding suitable conditions that recapitulate both the mechanical as well as biochemical environment of the nucleus in isolation may prove challenging.