Abstract

Despite increasing need to boost the recruitment of underrepresented populations into cancer trials and biobanking research, few tools exist for facilitating dialogue between researchers and potential research participants during the recruitment process. In this paper, we describe the initial processes of a user-centered design cycle to create a standardized research communication tool prototype for enhancing research literacy among individuals from underrepresented populations considering enrollment in cancer research and biobanking studies. We present qualitative feedback and recommendations on the prototype's design and content from potential end users: five clinical trial recruiters and ten potential research participants recruited from an academic medical center. Participants were given the prototype (a set of laminated cards) and were asked to provide feedback about the tool's content, design elements, and word choices during semi-structured, in-person interviews. Results suggest that the prototype was well received by recruiters and patients alike. They favored the simplicity, lay language, and layout of the cards. They also noted areas for improvement, leading to card refinements that included: addressing additional topic areas, clarifying research processes, increasing the number of diverse images, and using alternative word choices. Our process for refining user interfaces and iterating content in early phases of design may inform future efforts to develop tools for use in clinical research or biobanking studies to increase research literacy.

Keywords: Biobanking, clinical trials, cancer research, minority and underrepresented populations, patient communication

Introduction

Cancer researchers are struggling to increase recruitment of underrepresented populations into clinical trials and biospecimen research. Limited diversity in study populations may result in fewer samples available to scientists, limited therapeutics for minority-specific tumor pathology, and unequal distribution of the benefits and risks of research [1, 2]. Patient barriers that have been the primary focus of research on clinical trials participation for underrepresented populations include lack of insurance coverage, high out-of-pocket expenses, fear, suspicion, concerns regarding negative side effects and invasive procedures, and lack of awareness about health research studies [3-7]. However, low research literacy, or limited understanding of research processes, may also be a key contributor [8]. Limited research literacy and unfamiliarity with research concepts may also result in individuals consenting to participate without comprehending the full procedures, risks, benefits, and alternatives of participating in research [9].

Data suggest that research participants only understand between 30% to 81% of the information presented to them and not all the concepts essential for true informed consent [10, 11]. Particularly difficult research concepts include: the experimental nature of trials, risks and benefits, alternatives to treatment, voluntarism, and randomization [10, 12, 13]. The length and language of consent forms may exacerbate comprehension challenges [14, 15] and many study participants may not be reading consent forms at all [16]. These challenges may disproportionately affect patients with lower education and literacy levels, many of whom are from underrepresented populations [16, 17]. Strategies are needed to address the reality that researchers often fail to deliver adequate study information to participants [9].

In response, we sought to develop a standardized research communication tool to facilitate dialogue between researchers and potential study participants that would promote research literacy. Developed in conjunction with 28 partner institutions associated with the Cancer Disparities Research Network, under the auspices of the Biobanking Management Program (BMaP) [18], this tool is intended to empower participants to make fully informed decisions when considering enrollment in cancer clinical trials and biobanking research initiatives. In this paper, we describe the initial processes of a user-centered design cycle for refining the design and content of this research communication tool.

Materials and Methods

Overview of design

User-centered design broadly describes design processes that fully explore the needs and perspectives of users and the intended uses of a product [19]. End-users are central to the development process. Most typically used in the design of computerized systems, where prototypes (more limited versions) can be produced and tested, user-centered design principles have contributed to the ubiquity of technology in our daily lives. In user-centered design cycles, thorough investigations of user needs are conducted at the very beginning of the design project, followed by collection of feedback leading to iterative refinement of products [19]. We elected to involve end-users in a similar participatory design process, since developing a communication tool – regardless of format – is inherently risky in that it may fail to address user needs and stakeholder demands despite best intentions. Ultimately, prototyping and testing throughout the design process enables refinements based on user feedback and enables iteration of designs before a tool is fully operational.

In the first phase of this study, we identified user needs, developed a communication tool prototype, and solicited initial feedback about the design and content from end users – clinical trial recruiters and potential research participants. This manuscript focuses on findings from phase one. Phase two is the cognitive and usability testing of the next iteration of the prototype specifically among medically underserved communities. The Institutional Review Board at Northwestern University approved all study protocols.

Identifying user needs

Initial impetus for a standardized research communication tool stemmed from the shared goals of the Cancer Disparities Research Network (CDRN) partner institutions, under the auspices of the Biobanking Management Program (BMaP) [18]. Funded by the National Cancer Institute's Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, BMaP seeks to improve minority and underrepresented populations’ participation in clinical trials and biobanking research. The regional network spans 15 states from the Midwest to the Northeast. According to a recent regional assessment, nearly half of CDRN biospecimen facilities have conducted community education and outreach to promote biospecimen collection, but only a few reported specific efforts to engage minority populations [18].

A series of meetings with CDRN stakeholders was held to identify gaps. Needs expressed by CDRN researchers, clinicians, pathologists, administrators, recruiters, and community health educators, along with a community education program [20] and an exhaustive literature review of research literacy among the general public overall and underrepresented populations in particular, resulted in the decision to develop a research communication tool [18]. Objectives were identified for the tool and included: (1) increasing research literacy among potential participants, and (2) facilitating dialogue between clinical trial recruiters and potential research participants. The tool was not intended to be a persuasive tool, but rather one for allaying fears and reducing barriers to participation. During this stage of the design process, several research concepts were identified for inclusion in the communication tool. These included: understanding of research, withdrawing from a study, collection of and access to personal health information, definition of human samples, length of sample storage, informed consent, meaning of a signature on the consent form, and randomization (Table 1) [10, 12, 13].

Table 1.

Communication tool prototype

| Section of tool | Topic/card title |

|---|---|

| Part 1: Basic research information | • What is clinical research?a • What is standard of care?b • How does this study relate to my care? • What is informed consent?a • What does my signature mean? • Why would I want to join? • What are the different types of clinical research?a • Why wouldn't I want to join? |

| Part 2: Trial specific information |

Biobanking information: • What are samples? • How are samples collected? • What is biospecimen banking? • What information is connected to my sample?a • How long are my samples stored? Clinical trial information: • What is a treatment group? a • What is a control group? • What is a placebo? • What is randomization? • Blinded/Double blinded studies b • Phases of clinical trials b Healthy participants in research: • If I am healthy why do I need to participate? |

| Part 3: Patient rights | • What are my rights as a research participant? b • Can I change my mind? • How is my identity protected? • Who has access to my information? • Are there any costs or payments for participating in the study?a • If I decide to join what happens next?a • Will I find out the results of the research? b |

revisions made to card

new card created following participant feedback

Development of a prototype

Once we identified the objectives of the tool and research concepts for inclusion, we opted for simple design solutions in the form of a paper prototype. Paper prototyping has long been used by designers for refining user interfaces and iterating content in early phases of design [21]. We presented research concepts in a set of 33 interchangeable laminated flashcards (each 8”×5”) organized into three parts with question-answer format subsections (Table 1). Part 1 introduced research concepts standard across studies. Part 2 presented research concepts specific to biobanking, clinical trials, or studies with healthy participants – use of these cards can be tailored to study protocol. Part 3 presented information about patient rights standard across studies. The tool also included cards for introduction, myths and truths, and multiple (conversation starter) prompts. We followed federal plain language guidelines throughout, used headings, bulleted lists, short sentences, and sections to break information into visually manageable and readable segments [22, 23]. Research terminology were described in lay language (4th - 10th grade reading levels per the Flesch-Kincaid readability metric) and supported by images. CDRN partners provided input on the tool's development throughout this phase of the design cycle.

Interviews with potential end users

Once we cemented a prototype, we solicited feedback from potential end users via semi-structured one-onone interviews with a purposive sample of patients and clinical trial recruiters from an urban academic medical center in the Greater Chicago area. Eligible patient participants were men and women 18 years of age or older who were referred by clinic staff and able to read and speak English, since the prototype was in English. Eligible clinical trial recruiters were employed at the academic medical center and actively recruiting for research studies. Both clinical trial recruiters and patients were recruited through email blasts, cancer center newsletters, and presentations at staff meetings.

After describing the study and providing participants with a study information sheet, we obtained verbal consent and asked participants to view the tool on their own. They were given a highlighter pen and were instructed to mark cards for which they had specific feedback. Afterwards, participants were asked open ended questions soliciting their overall impressions of the tool, opinions regarding the usefulness of the content, recommendations for additional content, likes and dislikes about the design elements (e.g., images, layout), and word choices. All interviews were conducted by the authors (ST, ER) at the urban academic medical center and lasted 30-45 minutes. Authors took detailed notes during the interviews. Notes were then analyzed for common themes using the constant comparative method [24]. Recommended modifications to the communication tool were consolidated and discussed among members of the research team to guide the next iteration of the communication tool.

Results

Participant characteristics

Five clinical trial recruiters and ten patients provided feedback on the prototype. Patients came from a range of racial/ethnic backgrounds (self-reported), research experiences (with/without prior research participation), and medical experiences (with/without a cancer diagnosis). Of the ten patient participants, nine were female, four were African American, two were Hispanic, and four were White. Half reported previous research participation, although none reported previous participation in biobanking research. Seven of the ten patients had a cancer diagnosis. Participants were between 18-61 years old and consistent with the patient population of our academic medical center, most patients had some college education. Recruiters had between 3-8 years of experience and reported involvement in recruitment efforts for a variety of study types and cancer topics.

Overall impressions and feedback

Overall, clinical trial recruiters and patient participants were receptive to the communication tool and believed it would be useful during the recruitment processes. They indicated that the cards were informative, easy to read, a good starting point for conversation, and explained research concepts in simple language. Several recruiters had described specific challenges when recruiting lower literacy individuals and felt that this tool would be particularly useful for patients who struggle with research misconceptions (e.g., concerns about not getting standard of care, being a “guinea pig”) and who are skeptical of research from the moment they are approached. In general, we had sought to provide balanced information (e.g., by bringing attention to the risks associated with research), but some patient participants suggested more blatantly weaving the immediate and long-term benefits of participating in research throughout the communication tool. Recruiters echoed these sentiments, noting that depending on the study, patients need to hear that there may be direct benefits as a result of participation. One patient suggested appealing to people's goodwill: “[Your] participation is benefiting someone else as well as yourself. Someone participated in research before to benefit you today and you can do it as well.”

Recommendations for additional research content

Both recruiters and patients recommended additional research content/topic areas as well as some alternative approaches to a topic.

Part 1: Basic research information

In this section of the tool, recruiters and patients suggested adding details to cards and/or creating cards for additional topic areas. Recruiters believed that more information than what was presented in the prototype was needed to convey that informed consent is required for participation. Based on that feedback, we added details to the next iteration of the tool to impart that an individual needs to provide verbal or written permission (consent) in order to participate in research. We emphasized the importance of understanding essential elements of the study prior to providing consent and also inserted information that patients should be given time to make a decision and the opportunity to take consent forms home to review. Patient participants on the other hand, expressed mostly concerns about not receiving treatment if assigned to the control group. In response, we created a “What is standard of care?” card in the next iteration of the tool.

Part 2: Trial specific information

Several areas for improvement were noted for this section of the prototype and its biobanking and clinical trials subsections. With regards to biobanking, recruiters pointed out gaps in information. These gaps were supported by the questions raised by patient participants about biobanking logistics. In response to the feedback, we added details about the length of sample storage, described how samples will be utilized for research, specified that samples are banked for a specific study or for future yet to be defined research, and clarified that once samples are coded, personal identifiers are removed and cannot be linked to individuals. The trial specific section initially contained information regarding healthy participants focused on biobanking in research, but participants recommended that we generalize the topic to describe how healthy patients might contribute to all clinical research.

The clinical trials section received many suggestions for improvement from potential end users. A patient who had participated in different phases of clinical research suggested that the tool should describe the risks and long-term effects associated with involvement in multiple phases. In response, a “Phases of clinical trials” card was added to familiarize participants with the safety, dosage, and risks generally attributed to each clinical trial phase. When patients were asked to provide feedback on the randomization process card, patients largely expressed their distrust of the randomization process. This reaction resulted in us modifying the next iteration of the tool with information that a computer randomly assigns participants, that consent forms specify chances of group assignment, that the participant and/or treating physician might not know the group assignment, and creating a “Blinded and Double Blinded” studies concept card.

Part 3: patients’ rights

Overall feedback in this section was positive, but recruiters felt it would be helpful if more details were added to this section that (1) reassured participants that their rights would not be compromised if they declined participation, (2) clarified how patient privacy information is safeguarded, and described the withdrawal process in greater depth. In response to this feedback, we created a “What are my rights as a research participant?” card underscoring that participants have the right to be treated with respect, ask for an interpreter, and receive materials in a preferred language. We also inserted new details about how personal identifiers are removed, that only “approved” research team members have access to patient information, and that published data does not include personal identifiers. Recruiter's recommendations for greater detail of the withdrawal process led to new verbiage that information about leaving a study is provided on the consent form and that for biobanking, samples may be used up to the point that a participant formally withdraws from a study.

Acceptability of design elements

Participants commented that the card size was appropriate, color borders were appealing, font size was easy on the eyes, and that the images contributed to a reader friendly layout. They noted that the images on cards did help to explain concepts, but many recommended that the pictures should be more diverse and representative of all populations – a suggestion we heeded in the next iteration of the tool.

Word choice

Interviews with potential end users and review of notations they marked on the cards themselves illuminated several terms that needed definitions or needed to be replaced. For example, the “What are the different types of clinical research?” card was not well-received (we had underlined and bolded words such as “epidemiological”). We subsequently de-emphasized the technical terms in the next iteration of the tool, choosing instead to draw attention to the explanation of the term, written with simple sentence structure and in plain language. User feedback about stigmas associated with particular word choices led to us replace “scientist” (which reminded patients of experiments) with the term “researcher” and “sick (which may allude to just acute or chronic illnesses) with the term “unhealthy.” Moreover, participants’ objection to the term “leftover samples” led to the use of “unused portions” in the next iteration of the tool to convey that nothing extra is taken from patients.

Discussion and conclusion

This study is among the first to describe the initial processes of a user-centered design cycle for refining the design and content of the research communication tool for increasing research literacy and facilitating dialogue between clinical trial recruiters and potential research participants. We identified user needs, developed a prototype, and solicited initial feedback from end users about the prototype's research content, design elements, and word choices. Feedback from a purposive sample of recruiters and patients suggests that the tool was well received. They favored the prototype tool's simplicity, lay language, and readability. Users also noted areas for improvement, leading to card refinements that included addressing additional topic areas, clarifying research processes, increasing the number of diverse images, and using alternative word choices.

Research has shown that visual multimedia modes of presenting information may be effective among populations with low literacy [25], but the positive feedback regarding the simplicity of our prototype provides support to the use of paper/flashcard formats. Unlike videos and related multimedia formats, cards may give recruiters the ability to quickly identify specific segments to present to participants during the recruitment process. Although we aimed to minimize the amount of text in the tool, we were surprised to find that users preferred more information in the tool, rather than less. As a result, the next iteration of the tool contained more text. This additional information could make the tool a more versatile resource for recruiters in their efforts to bridge communication gaps. However, we acknowledge that preference among patient participants for more information may in part reflect the audience we recruited (many were cancer patients with clinical trial experience). Feedback from those who have participated in clinical trials is valuable, since their opinions about research processes come from experience rather than the abstract.

Several limitations to this study should be noted. Foremost, our purposive sample of clinical trial recruiters and patients from a single urban academic medical center limits generalizability of our findings. In particular, our decision to solicit feedback from cancer patients at the academic medical center resulted in recruitment of patients with higher education level than anticipated. Second, our limited sample size did not allow us to disentangle feedback provided by different types of audiences, although there were some indications (data not presented) that participants with past research experience desired greater emphasis on study specific details and that those without prior research experience had fewer questions or suggestions to give.

Despite this study's limitations, we obtained invaluable feedback of the communication tool from potential end users. User-centered design principles enabled us to prototype a tool, receive feedback from potential end users, and quickly make substantial improvements to the next iteration. This process is critical for our objectives, given that many research and informed consent concepts are particularly difficult for people to understand [3, 10, 11]. This design process also illuminated additional research concepts in need of attention, such as standard of care, personal identifiers linked to samples, and distrust of the randomization process. We made modifications (ranging from additional cards to additional images and wording changes) to improve these areas of the tool. However, recruiters may still need to devote concerted attention to ensuring that potential participants understand particularly challenging research concepts. This will be more thoroughly investigated in a subsequent phase when we gather data on user experiences with the communication tool during patient-recruiter interactions. In addition, some research concepts may become more pertinent to later stages of the research process, so usability of this communication tool across various stages of research among enrolled participants is another promising avenue of study for promoting study retention and future participation in other research.

Increasing clinical trial and biobanking participation among underrepresented populations is a pressing need. A standardized research communication tool is poised to address communication challenges in the recruitment process by facilitating conversations between researchers and potential study participants. Next steps in this participatory, user-centered design process include cognitive and usability testing of the next iteration of the tool among diverse underrepresented communities and recruiters specializing in recruitment in these communities and translating the tool to other languages (e.g., Spanish). Future efficacy trials will be needed to investigate the communication tool's impact on research literacy and efficacy in facilitating discussions between recruiters and potential participants.

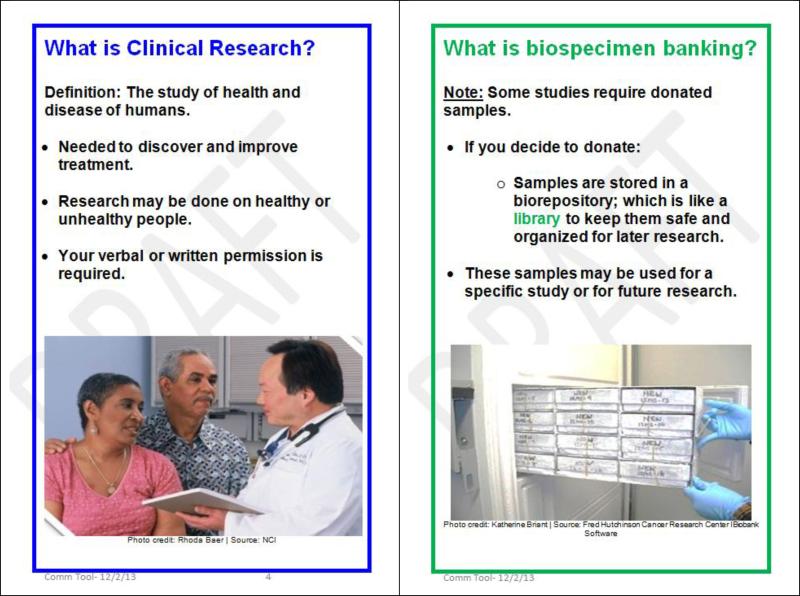

Figure 1.

Selected excerpts from the communication tool

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute's Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities Patient Navigation Research Grants (U01CA116874, 340CA1168875-04-53, 5U01 CA116875-05S4) and NUNEIGHBORS: A Social Science Partnership to Reduce Cancer Disparities (P20CA165592 (NU), CA165588 (NEIU), P20CA165592-02S1, P20CA165592-02S2).

The authors are grateful for the Principal Investigators, Biospecimen Core Facility Administrators and Directors, and research staff across CDRN who have provided guidance on the development of this communication tool. We especially want to thank the research participants and clinical trial recruiters who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Samantha Torres, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine 633 N. St Clair, Suite 1800 Chicago, IL 60611, USA.

Erika E. de la Riva, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago IL.

Laura S. Tom, Institute for Public Health & Medicine, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago IL.

Marla L. Clayman, Health & Social Development Program, American Institutes for Research, Chicago IL.

Chirisse Taylor, Las Vegas Minimally Invasive Surgery, Women's Pelvic Health Center, Las Vegas NV.

Xinqi Dong, Department of Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago IL.

Melissa A. Simon, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago IL.

References

- 1.Swanson GM, Bailar JC., 3rd Selection and description of cancer clinical trials participants--science or happenstance? Cancer. 2002;95(5):950–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haynes MA, Smedley BD, editors. The Unequal Burden of Cancer: An Assessment of NIH Research and Programs for Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved. The National Academies Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colon-Otero G, et al. Disparities in participation in cancer clinical trials in the United States : a symptom of a healthcare system in crisis. Cancer. 2008;112(3):447–54. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford JG, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford JG, et al. Knowledge and access to information on recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2005;(122):1–11. doi: 10.1037/e439572005-001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne MM, et al. Participation in Cancer Clinical Trials: Why Are Patients Not Participating? Med Decis Making. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0272989X13497264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivers D, et al. A systematic review of the factors influencing African Americans' participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(2):13–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simon CM, Kodish ED. Step into my zapatos, doc: understanding and reducing communication disparities in the multicultural informed consent setting. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48(1 Suppl):S123–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paasche-Orlow MK, Taylor HA, Brancati FL. Readability standards for informed-consent forms as compared with actual readability. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(8):721–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa021212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flory J, Emanuel E. Interventions to improve research participants' understanding in informed consent for research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2004;292(13):1593–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cortes DE, et al. How to achieve informed consent for research from Spanish-speaking individuals with low literacy: a qualitative report. J Health Commun. 2010;15(Suppl 2):172–82. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamariz L, et al. Improving the Informed Consent Process for Research Subjects with Low Literacy: A Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2133-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falagas ME, et al. Informed consent: how much and what do patients understand? Am J Surg. 2009;198(3):420–35. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jefford M, Moore R. Improvement of informed consent and the quality of consent documents. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(5):485–93. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jefford M, et al. Satisfaction with the decision to participate in cancer clinical trials is high, but understanding is a problem. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(3):371–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0829-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenzen B, Melby CE, Earles B. Using principles of health literacy to enhance the informed consent process. Aorn j. 2008;88(1):23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breese PE, et al. Education level, primary language, and comprehension of the informed consent process. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2007;2(4):69–79. doi: 10.1525/jer.2007.2.4.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simon MA, et al. Improving Diversity in Cancer Research Trials: The Story of the Cancer Disparities Research Network. J Cancer Educ. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0617-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abras C, Maloney-Krichmar D, Preeces J. Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2004. User-Centered Design. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill TG, et al. Evaluation of Cancer 101: an educational program for native settings. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(3):329–36. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0046-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyder C. Paper prototyping: The fast and easy way to design and refine user interfaces. Morgan Kaufmann Publishers; San Francisco, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Plain Language Action and Information Network Federal Plain Language Guidelines (Revision 1) 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CDC Clear Communication Index: A Tool for Developing and Assessing CDC Public Communication Products (User Guide) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Office of the Associate Director for Communication; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis Social Problems. 1965:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keselman A, et al. Developing informatics tools and strategies for consumer-centered health communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15(4):473–83. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]