Abstract

OBJECT

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a common complication of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH). The time period of greatest risk for developing DVT after aSAH is not currently known. aSAH induces a prothrombotic state, which may contribute to DVT formation. Using repeated ultrasound screening, the hypothesis that patients would be at greatest risk for developing DVT in the subacute post-rupture period was tested.

METHODS

One hundred ninety-eight patients with aSAH admitted to the Oregon Health & Science University Neurosciences Intensive Care Unit between April 2008 and March 2012 were included in a retrospective analysis. Ultrasound screening was performed every 5.2 ± 3.3 days between admission and discharge. The chi-square test was used to compare DVT incidence during different time periods of interest. Patient baseline characteristics as well as stroke severity and hospital complications were evaluated in univariate and multivariate analyses.

RESULTS

Forty-two (21%) of 198 patients were diagnosed with DVT, and 3 (2%) of 198 patients were symptomatic. Twenty-nine (69%) of the 42 cases of DVT were first detected between Days 3 and 14, compared with 3 cases (7%) detected between Days 0 and 3 and 10 cases (24%) detected after Day 14 (p < 0.05). The postrupture 5-day window of highest risk for DVT development was between Days 5 and 9 (40%, p < 0.05). In the multivariate analysis, length of hospital stay and use of mechanical prophylaxis alone were significantly associated with DVT formation.

CONCLUSIONS

DVT formation most commonly occurs in the first 2 weeks following aSAH, with detection in this cohort peaking between Days 5 and 9. Chemoprophylaxis is associated with a significantly lower incidence of DVT.

Keywords: aneurysm, subarachnoid hemorrhage, deep vein thrombosis, vascular disorders

Venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.19 Among all neurosurgical patients, the estimated incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) ranges broadly from 0% to 34%.13 DVT is a common complication of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) associated with increased death and disability. 1,3,5,11,14–16 Two recent retrospective studies used screening ultrasound to estimate the incidence of DVT in aSAH to be 24%14 and 9.7%.15 A large retrospective review of nearly 16,000 patients from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database found that the incidence of DVT was 3.5% and the incidence of DVT and pulmonary embolism was 4.4%.10

Methods of DVT prophylaxis in aSAH include mechanical therapy, such as the use of sequential compression devices (SCDs), and pharmacological therapy, using unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, and/or other anticoagulants.17 Pharmacological therapy is thought to be more effective at preventing DVT but may increase risk of intra- and extracranial bleeding complications.2

The natural history of DVT formation after aSAH remains poorly understood despite its contribution to morbidity and mortality. Patients with aSAH may be at higher risk for DVT due to immobility. Aneurysmal hemorrhage also induces a prothrombotic state, which may contribute to DVT formation.6,12 Importantly, the time period of greatest risk for developing DVT after aSAH is not known. As a result, optimal timing of DVT prophylaxis and duration of therapy are uncertain.4,17

This study retrospectively examines a cohort of consecutive aSAH admissions to the Oregon Health & Science University Neurosciences Intensive Care Unit over a 4-year period between 2008 and 2012. During this time, pharmacological DVT prophylaxis was not routinely used, in favor of mechanical prophylaxis with SCDs combined with frequent repeated ultrasound screening (every 5 days on average).

We hypothesized that the highest risk of DVT development would occur in the subacute period following rupture. To approximate this, we determined the number of DVTs detected during a time period with the highest risk of vasospasm (3–14 days), which would combine a period of significant patient immobility with the potential of prothrombotic activity due to the aSAH disease process. We compared the DVTs detected during this time with those detected in the acute (0–3 days) and chronic (> 14 days) periods. The time period at risk for developing DVT was defined as the number of days between the last known normal ultrasound examination (or onset of bleed) and DVT detection. From this, we estimated the percent risk of developing DVT per hospital day. Finally, we performed multivariate regression analysis to determine which patient- and stroke-dependent variables were significantly associated with DVT formation.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for a retrospective chart review. A total of 268 patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage were identified from the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Department of Neurosurgery database from April 2008 to March 2012. Of these, 217 patients underwent at least 1 lower-extremity Doppler ultrasonography screening during their hospitalization, and 198 patients had documented aneurysmal rupture. Per OHSU protocol, sequential ultrasound imaging was used to follow DVT development after aSAH. Chart review was performed to determine whether each patient developed a lower-extremity DVT during the hospitalization and at what time point it was diagnosed. A total of 598 ultrasound scans were performed on the 198 patients included in the study, for an average of approximately 3 ultrasounds per patient, and the average interval between ultrasound screenings was 5.2 days. The screening frequency was variable and depended on the protocol in place at the time and on the preferences of the attending neurointensivist. Additional demographic and clinical features of each patient were recorded including age, sex, length of hospital stay, severity of bleed (Hunt and Hess grade and Fisher scores), location of the aneurysm, the mechanism by which the aneurysm was secured (surgical vs endovascular), whether an external ventricular drain (EVD) was needed, and whether a patient became ambulatory at any point during the hospitalization. Descriptive statistics (median and interquartile range [IQR] for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were used to describe clinical data by group assignment. Group comparisons regarding categorical variables were performed using Fisher’s exact and chi-square tests, and ordinal comparisons were made with the Mann-Whitney test. Multivariate analysis was performed using linear regression. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (IBM Corp.). Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Graphs were created with Microsoft Office 2007 (Microsoft Corp.).

Results

Incidence of DVT

Table 1 shows a comparison between the characteristics of patients in the DVT and non-DVT groups. DVT was detected in 42 (21%) of 198 patients (3 of whom were symptomatic), compared with 156 (79%) of 198 without DVT. There was no significant difference in sex or the mean age between the 2 groups at the time of rupture. Other factors that were not significant in the initial univariate analysis included development of vasospasm, aneurysm location, type of intervention performed, and the mean number of days to ambulation. Univariate analyses of the Hunt and Hess grade and Fisher scores were performed using a Mann-Whitney U rank-order test. Patients who developed DVT were more likely to be using mechanical prophylaxis alone, were more likely to have EVD placement, had a longer mean length of stay, were less likely to be ambulatory at discharge, and had an overall worse discharge outcome.

TABLE 1. Grouped characteristics between patients diagnosed with DVT on ultrasound screening (n = 42) and patients without DVT (n = 156).

| Characteristic | w/ DVT (n = 42) | w/o DVT (n = 156) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 59.0 ± 13.6 | 55.2 ± 12.7 |

| Median (IQR) | 57.5 (50–67) | 53.0 (47–63) |

| Male, n (%) | 17 (40.4) | 49 (31.4) |

| Hunt & Hess score, median (IQR)* |

3.5 (2–4) | 3.0 (2–4) |

| Fisher score, median (IQR)* | 4.0 (3–4) | 4.0 (3–4) |

| Venous thrombosis | ||

| Prophylaxis, n (%) | ||

| SCDs only† | 41 (97.6) | 122 (78.2) |

| Chemoprophylaxis† | 1 (2.4) | 34 (21.8) |

| Symptomatic, n (%) | 3 (7.1) | NA |

| Ultrasound frequency, days | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 5.2 ± 3.3 | 5.0 ± 2.1 |

| Median (± SD) | 4.5 (3–6) | 4.5 (3.5–6) |

| aSAH management & treat- ment |

||

| Vasospasm, n (%) | ||

| Angiographically diagnosed | 20 (47.6) | 82 (52.6) |

| Treated w/ IA therapy | 12 (28.6) | 50 (32.1) |

| Location, n (%) | ||

| Anterior | 23 (54.8) | 105 (67.3) |

| Posterior | 19 (45.2) | 51 (32.7) |

| Intervention, n (%) | ||

| Surgical | 29 (69.0) | 125 (80.1) |

| Endovascular | 10 (23.8) | 29 (18.6) |

| None | 3 (7.1) | 2 (1.3) |

| EVD placement† | 33 (78.6) | 93 (59.6) |

| Clinical outcome | ||

| Length of stay, days | ||

| Mean (± SD)† | 22.3 ± 12.0 | 17.0 ± 8.8 |

| Median (± SD) | 20.0 (15–27) | 15.0 (12–20) |

| Time to ambulation, days | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 9.5 ± 6.1 | 7.5 ± 6.9 |

| Median (± SD) | 8.5 (5–15) | 5.0 (3–11) |

| Ambulatory at discharge, n (%)† |

22 (52.4) | 115 (73.7) |

| Discharge location, n (%)† | ||

| Home | 12 (28.6) | 86 (55.1) |

| Intermediate care | 20 (47.6) | 52 (33.3) |

| Hospice | 2 (4.8) | 4 (2.6) |

| Dead, n (%) | 8 (19.0) | 14 (9.0) |

IA = intraarterial; NA = not applicable.

Scores between groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for nonparametric, ordinal variables.

Significant characteristics in univariate analysis (p < 0.05).

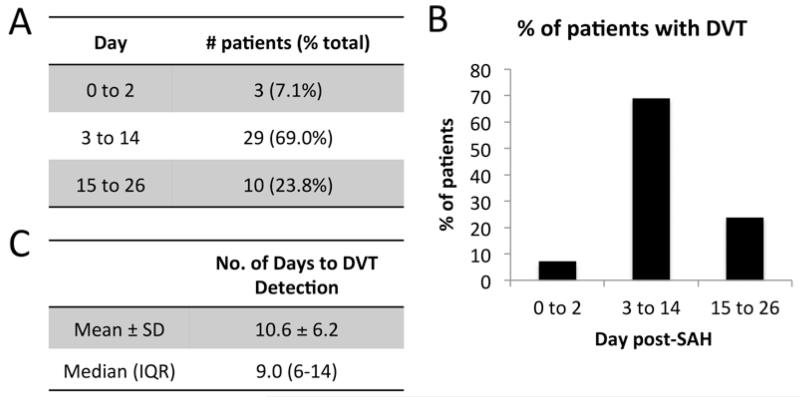

We tested the primary hypothesis by determining the number of DVTs that were detected in the subacute time period corresponding to the highest risk for vasospasm (Fig. 1A and B). Twenty-nine (69%) of 42 patients were diagnosed with DVT between Days 3 and 14. This frequency of DVT diagnosis was significantly greater than the 3 cases (7%) diagnosed at Days 0–3 and the 10 cases (24%) diagnosed after Day 14 (p < 0.05). For patients diagnosed with DVT, the mean and median number of days for DVT detection was 10.6 ± 6.3 and 9 (IQR 6–14), respectively (Fig. 1C).

FIG. 1.

Day of DVT detection grouped by acute (Days 0–2), subacute (Days 3–14), and chronic (after Day 14). Number (A) and percentage (B) of patients detected in each group. Number of days from hospital admission to DVT detection (C).

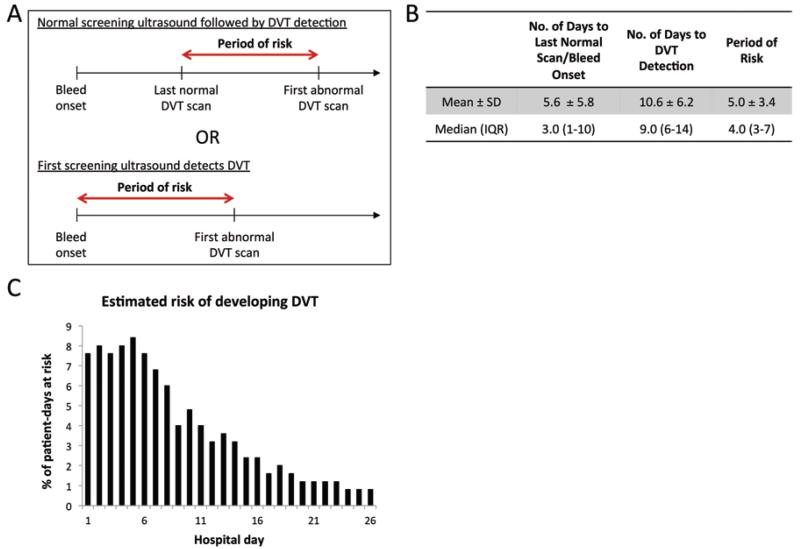

Although DVTs were detected at a high rate between Days 3 and 14, the day of detection may not accurately represent the day of DVT formation. In fact, DVT formation may have occurred at any time between the prior normal DVT scan (or day of hospital admission) and the day the DVT was ultimately detected by ultrasonography. To account for this variability, we calculated the period of risk, defined as the time period between the last normal DVT scan and the first abnormal DVT scan (Fig. 2A). If the DVT was diagnosed at the first ultrasound screening, the period of risk began from the day of admission to the day of that first ultrasound examination.

FIG. 2.

Period of risk for DVT formation. A: Schematic overview showing the periods of risk. B: Number of days from hospital admission to the last normal scan/bleed onset and DVT detection, with the difference between these being the period of risk. C: Bar graph showing the estimated risk for developing DVT for any given post-admission day. Figure is available in color online only.

The mean period of risk was 5.0 ± 3.4 days (median 4 days, IQR 3–7 days) (Fig. 2B). To calculate an estimated risk of developing DVT by day, we first determined the total number of patient-days at risk in our cohort. This is the number of days at risk for each individual patient, summed for all 198 patients. Then, for each hospital day after admission, the number of patients with DVT who were at risk on that day were tallied. Dividing this number by the total number of patient-days at risk yields the percent of risk for any given day during the hospitalization (Fig. 2C). We found that the highest risk occurred in the first week after rupture, with approximately 7%–8% risk of DVT development per day. After Day 8, the risk fell to less than 5% per day, and after Day 14, risk fell to less than 3% per day.

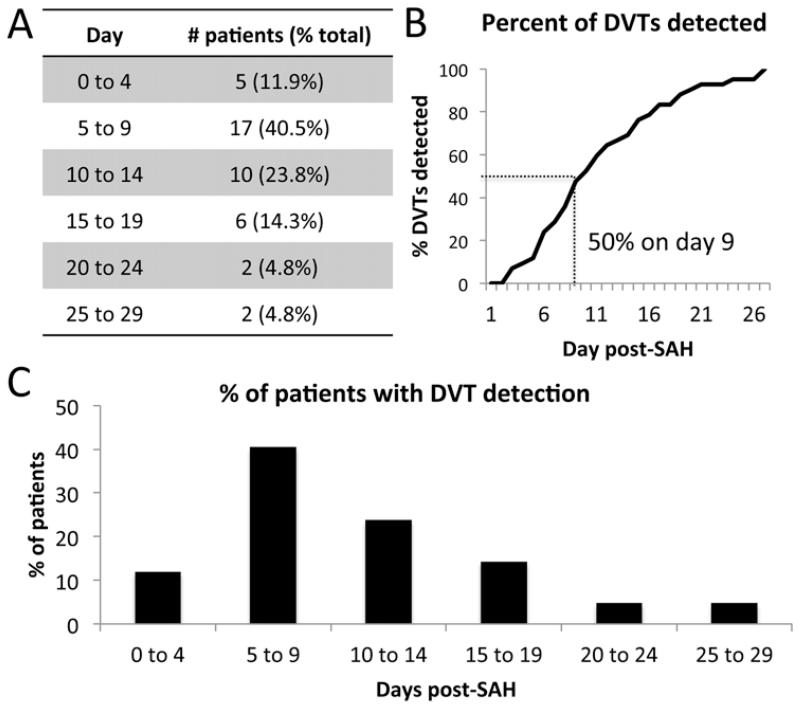

To obtain a more precise understanding of DVT formation in our cohort, we sought a smaller bin size to group DVTs by detection date. A large bin size, as used in Fig. 1, with 3 categories (acute, subacute, and chronic), sacrifices time resolution; too small a bin size, however, may lead to error because of the time difference between DVT formation and detection. We chose a bin size of 5 days, equal to the average period of risk, because the time between when the DVT actually occurred and when it was detected would be smaller than the average period of risk. Forty percent of DVTs were detected in the hospital Days 5–9 period, a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared with 24% at 10–14 days, 14% at 15–19 days, 12% at 0–4 days, and 10% after Day 20 (Fig. 3A and C). The data, plotted as cumulative percentage in Fig. 3B, show that 50% of DVTs in this cohort were detected by hospital Day 9.

FIG. 3.

Day of DVT detection grouped by the mean period of risk. Number (A) and percent (C) of patients detected in each group. Line graph (B) showing the cumulative percentage distribution of DVTs detected by hospital day.

Risks for DVT Formation

Multivariate analysis was performed to determine the individual contribution of risks to DVT development (Table 2). Nonsignificant contributors in the multivariate analysis included age, sex, vasospasm, aneurysm location, and type of intervention. In contrast, DVT development was significantly associated with increased length of hospital stay and use of mechanical prophylaxis only. Two attributes which were significant in the univariate analysis, EVD placement and ambulatory status during hospitalization, proved to be nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis.

Table 2. Results of multivariate regression analysis, with presence or absence of DVT as the dependent variable and the listed characteristics as independent variables.

| Characteristic | OR | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Length of stay | 1.357 | 0.000 |

| Age | 1.095 | 0.224 |

| Sex | 0.906 | 0.152 |

| DVT prophylaxis (SCDs alone vs chemoprophylaxis) | 0.771 | 0.000 |

| Vasospasm | 0.938 | 0.405 |

| Aneurysm location (anterior vs posterior) | 0.894 | 0.119 |

| Aneurysm intervention (coiled vs clipped) | 1.006 | 0.928 |

| EVD placement | 1.004 | 0.952 |

| Ambulatory during hospitalization | 1.111 | 0.144 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study that attempts to identify the time period of greatest risk for DVT development after aSAH. More than two-thirds of the DVTs in this cohort were discovered between postrupture Days 3 and 14. In our targeted analysis based on the frequency of repeated ultrasound screening, 40% of DVTs were detected between hospital Days 5 and 9. This suggests that DVT development occurs in a unimodal distribution, with highest risk peaking around Day 7. In the multivariate analysis, the only factors significantly associated with DVT were length of hospitalization and use of DVT prophylaxis. Two characteristics that were significant in the univariate analysis, EVD placement and ambulatory status during hospitalization, became nonsignificant in the multivariate analysis.

Several factors were found to not have a significant impact in DVT development. Importantly, the clinical severity, measured by Hunt and Hess grade and Fisher scores, and open surgical intervention did not independently increase the likelihood of developing DVT. Angiographic vasospasm also was not associated with DVT, suggesting that the relationship between DVT development and the time period highest for vasospasm may be coincidental.

Overall, the number of DVTs detected in this cohort (21%) is comparable to older studies of DVT in aSAH14 as well as general neurosurgical cohorts,7 but higher than reported in other, more recent studies.11,15 Thirty-six of the 198 patients received pharmacological prophylaxis, and within that subgroup, the incidence of DVT was only 2.7% (1 of 36). The rate of symptomatic embolism, at 1.7%, is also comparable to past studies (although it represents only 3 cases). The discrepancy in reported rates of DVT is likely multifactorial. First, increased awareness of DVT complications may be leading to increased use of pharmacological prophylaxis and combination mechanical-pharmacological prophylaxis,5 which in turn may be decreasing the overall number of DVTs. The majority of patients in this study did not receive chemoprophylaxis, a practice which is becoming increasingly less common in the neurointensive care unit setting. Second, more sophisticated protocols for DVT prophylaxis, like weight-based dosing for heparin and more widespread use of enoxaparin and fondaparinux, may be contributing to the lower incidence of DVTs. Finally, variability in ultrasound screening frequency between studies may lead to differences in the numbers of asymptomatic DVTs detected.

The time course of venous thromboembolism in all hospitalized patients is not generally well understood and may depend on the underlying disease. The International Multicenter Trial, studying patients over 40 years of age “undergoing a variety of elective major surgical procedures,” found that 39% of DVTs occurred in patients without prophylaxis between the day of operation to the 2nd day, while 52% occurred between the 3rd and 6th days, and only 9% occurred after the 7th day. The comparison heparin arm had significantly fewer DVTs (7% vs 25% in the control arm), but a similar percentage breakdown (36%, 45%, and 19%, respectively).8 In a recent study comparing 2 types of orthopedic procedures, knee replacement was found to have a median of 7 days to occurrence of venous thromboembolism compared with 17 days in patients with hip replacement.18 It is also suggested that the location of DVT development is dependent on the type of surgery or injury suffered by the patient, for example pelvic vein thromboses in pelvic surgery, and that location plays a role in determining the likelihood of developing symptomatic pulmonary embolism.9 Together these data indicate that DVT development is a complex, heterogeneous process influenced by specific diseases as well as preexisting and acquired patient characteristics such as medical comorbidities and mobility during hospitalization.

One significant limitation of this study is the possibility that some patients may have entered the hospital with a preexisting DVT. These patients would have DVT detected on the initial screening ultrasound. Because only 7% of the patients (3 of 42) had documented DVT in the first 3 days of the hospitalization, it is likely that the number of patients who entered the hospital with DVT is low. An ideal study of the natural history of DVT formation would require screening at admission and daily afterward, a protocol that would be neither cost-effective nor likely to be beneficial toward clinical outcome. A second limitation is that the number of patients in this cohort is relatively small and limited to the experience of a single institution; it is unclear whether these results are generalizable across different neurointensive care unit environments.

Conclusions

In summary, these data provide the first evidence of the timing of DVT formation in aSAH. Our data suggest that DVT development occurs in a unimodal distribution, in the subacute period after aneurysmal rupture, peaking between postrupture Days 5 and 9. This observation should be prospectively validated with a rigorous screening protocol. Additional investigation is needed to determine whether targeted pharmacological prophylaxis and/or ultrasound screening around this time may be helpful to improve clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

DISCLOSURE This study was supported by the OHSU Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery. Dr. Hinson reports receiving support from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, award number 5K12HL108974-03, for the project described. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

ABBREVIATIONS

- aSAH

aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- DVT

deep vein thrombosis

- EVD

external ventricular drain

- IQR

interquartile range

- SCD

sequential compression device

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Liang. Acquisition of data: Liang, Su, Liu, Dogan. Analysis and interpretation of data: Liang, Su. Drafting the article: Liang, Hinson. Critically revising the article: Liang, Hinson. Reviewed submitted version of manuscript: Liang, Hinson. Approved the final version of the manuscript on behalf of all authors: Liang. Statistical analysis: Liang, Su. Administrative/technical/material support: Liang, Su. Study supervision: Liang.

References

- 1.Black PM, Baker MF, Snook CP. Experience with external pneumatic calf compression in neurology and neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:440–444. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Browd SR, Ragel BT, Davis GE, Scott AM, Skalabrin EJ, Couldwell WT. Prophylaxis for deep venous thrombosis in neurosurgery: a review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;17(4):E1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2004.17.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerrato D, Ariano C, Fiacchino F. Deep vein thrombosis and low-dose heparin prophylaxis in neurosurgical patients. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:378–381. doi: 10.3171/jns.1978.49.3.0378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diringer MN, Bleck TP, Claude Hemphill J, III, Menon D, Shutter L, Vespa P, et al. Critical care management of patients following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: recommendations from the Neurocritical Care Society’s Multidisciplinary Consensus Conference. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:211–240. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henwood PC, Kennedy TM, Thomson L, Galanis T, Tzanis GL, Merli GJ, et al. The incidence of deep vein thrombosis detected by routine surveillance ultrasound in neurosurgery patients receiving dual modality prophylaxis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;32:209–214. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0583-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirashima Y, Nakamura S, Endo S, Kuwayama N, Naruse Y, Takaku A. Elevation of platelet activating factor, inflammatory cytokines, and coagulation factors in the internal jugular vein of patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurochem Res. 1997;22:1249–1255. doi: 10.1023/a:1021985030331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iorio A, Agnelli G. Low-molecular-weight and unfractionated heparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism in neurosurgery: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2327–2332. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.15.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakkar VV, Corrigan TP, Fossard DP, Sutherland I, Shelton MG, Thirlwall J, et al. Prevention of fatal postoperative pulmonary embolism by low doses of heparin. An international multicentre trial. Lancet. 1975;2:45–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kearon C. Natural history of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I22–I30. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078464.82671.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kshettry VR, Rosenbaum BP, Seicean A, Kelly ML, Schiltz NK, Weil RJ. Incidence and risk factors associated with in-hospital venous thromboembolism after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21:282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel AP, Koltz MT, Sansur CA, Gulati M, Hamilton DK. An analysis of deep vein thrombosis in 1277 consecutive neurosurgical patients undergoing routine weekly ultrasonography. J Neurosurg. 2013;118:505–509. doi: 10.3171/2012.11.JNS121243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peltonen S, Juvela S, Kaste M, Lassila R. Hemostasis and fibrinolysis activation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:207–214. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.2.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raslan AM, Fields JD, Bhardwaj A. Prophylaxis for venous thrombo-embolism in neurocritical care: a critical appraisal. Neurocrit Care. 2010;12:297–309. doi: 10.1007/s12028-009-9316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ray WZ, Strom RG, Blackburn SL, Ashley WW, Jr, Sicard GA, Rich KM. Incidence of deep venous thrombosis after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:1010–1014. doi: 10.3171/2008.9.JNS08107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serrone JC, Wash EM, Hartings JA, Andaluz N, Zuccarello M. Venous thromboembolism in subarachnoid hemorrhage. World Neurosurg. 2013;80:859–863. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swann KW, Black PM, Baker MF. Management of symptomatic deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism on a neurosurgical service. J Neurosurg. 1986;64:563–567. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.4.0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vespa P. Deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:295–297. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White RH, Romano PS, Zhou H, Rodrigo J, Bargar W. Incidence and time course of thromboembolic outcomes following total hip or knee arthroplasty. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1525–1531. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.14.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White RH. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003;107(23 Suppl 1):I4–I8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078468.11849.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]