Abstract

A significant challenge in the design and development of biomaterial scaffolds is to incorporate mechanical and biochemical cues to direct organized tissue growth. In this study, we investigated the effect of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) loaded, crosslinked fibrin (EDCn-HGF) microthread scaffolds on skeletal muscle regeneration in a mouse model of volumetric muscle loss (VML). The rapid, sustained release of HGF significantly enhanced the force production of muscle tissue 60 days after injury, recovering more than 200% of the force output relative to measurements recorded immediately after injury. HGF delivery increased the number of differentiating myoblasts 14 days after injury, and supported an enhanced angiogenic response. The architectural morphology of microthread scaffolds supported the ingrowth of nascent myofibers into the wound site, in contrast to fibrin gel implants which did not support functional regeneration. Together, these data suggest that EDCn-HGF microthreads recapitulate several of the regenerative cues lost in VML injuries, promote remodeling of functional muscle tissue, and enhance the functional regeneration of skeletal muscle. Further, by strategically incorporating specific biochemical factors and precisely tuning the structural and mechanical properties of fibrin microthreads, we have developed a powerful platform technology that may enhance regeneration in other axially aligned tissues.

Keywords: tissue engineering, muscle regeneration, fibrin, microthreads, hepatocyte growth factor

1. INTRODUCTION

Volumetric muscle loss (VML) typically results from traumatic incidents such as those presented from combat missions, where soft tissue extremity injuries are present in 54% of cases, with 53% of these injuries involving soft tissue damage [1, 2]. These injuries lead to a devastating loss of musculoskeletal function because of the complete removal of large amounts of tissue, including its native basement membrane [3]. While skeletal muscle has innate repair mechanisms that are largely directed by the native architecture of the basement membrane, it is unable to compensate for large-scale injuries due to the destruction of this regenerative template and growth factor reservoir. The current standard of care for a large-scale skeletal muscle injury is an autologous tissue transfer from an uninjured site [4]. This challenging surgical procedure yields limited restoration of muscle function and can result in complications such as donor site morbidity, infection, and graft failure secondary to tissue necrosis [4, 5]. While muscle flaps may be a suitable treatment, as many as 10% of muscle flap surgeries develop complete graft failure, demonstrating the need for an alternative treatment [5, 6]. As such, there is a significant need to develop an off-the-shelf, biomimetic scaffold that directs functional skeletal muscle tissue regeneration within large defect sites.

Skeletal muscle regeneration is mediated by local progenitor cells known as satellite cells (SCs), which reside between the sarcolemma and basal lamina of muscle fibers [7, 8]. In small muscle wounds such as those from exercise, the basal lamina rapidly releases hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) to stimulate the activation and recruitment of SCs to the wound site [9–12]. Importantly, SC reentry into the cell cycle has been reported to be mediated solely by HGF [13, 14]. This immediate, rapid release of HGF occurs in the first 48–72 hours of injury, and is important to gather enough progenitor cells to repair large defects [12, 15]. However, prolonged HGF signaling will inhibit skeletal muscle regeneration, demonstrating that careful attention must be paid to the time scale that HGF is released into a VML defect [12, 16].

Acellular scaffolds engineered to direct the regeneration of VML injuries can be tuned via multiple design criteria to facilitate the recruitment of SCs to the injury site and create organized nascent myofibers. A simple method to increase the number of SCs at the injury site is to design scaffolding materials that enable the control release of inductive growth factors upon implantation. Recent studies focus on the revascularization of the tissue [17], or rely on the growth factors present in decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM) materials to direct regeneration [18, 19], but they do not address the role of SCs in directing skeletal muscle regeneration. HGF has been used in several studies to enhance the survival of implanted myoblasts, resulting in improved engraftment [20, 21]. A separate study incorporated HGF into gelatin scaffolds, and while there was an increase in regenerating myofibers, no functional analyses were performed [22]. While some of these studies report improvements in mechanical function [23], many studies using acellular ECM materials report that long term remodeling, between 3–6 months, is necessary for ECM scaffold-mediated functional recovery [24, 25]. These data suggest that the addition of an exogenous factor capable of stimulating rapid SC recruitment may facilitate functional recovery at earlier time points, as this would recapitulate regenerative cues missing in VML injuries and expedite the remodeling of the defect site.

An additional limitation of previous acellular strategies is that regenerating myofibers are often not parallel to the native myofibers, limiting the functional efficiency of the newly formed tissue [26–28]. This disorganized regeneration may be a result of the randomly aligned protein networks present in both decellularized ECM and the polymerization process involved in the formation of alginate or gelatin scaffolds. To guide the organized creation of myofibers within an injury site, we developed biomimetic biopolymer microthreads by extruding polymerized solutions of fibrinogen and thrombin into microthread patterns. These aligned fibrin microthread scaffolds have an architectural morphology that is similar to native skeletal muscle tissue and they direct cell alignment along the longitudinal axis of the microthread structure [29]. Results of initial implantation studies investigating the use of fibrin microthreads in a mouse model of VML showed that fibrin microthreads stimulate skeletal muscle regeneration, but noted that a decreased rate of degradation of the microthreads might enhance the microthread-mediated regenerative response [30]. To increase the persistence of microthreads in vivo, we developed a crosslinking strategy using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) that attenuates the in vitro degradation of fibrin microthreads (EDCn microthreads) without adversely affecting cell attachment, proliferation, or viability, suggesting that these crosslinked materials might be ideal for skeletal muscle regeneration [31].

This study investigated the ability of HGF loaded carbodiimide crosslinked microthreads to enhance regeneration of functional tissue in a mouse VML model. HGF was adsorbed onto EDCn fibrin microthreads (EDCn-HGF) to mimic its in vivo release kinetics after injury. We hypothesize that EDCn-HGF microthreads will increase the functional recovery of VML injuries in the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle by increasing the number of SCs directed to the injury site. We also examined the impact of HGF delivery on blood vessel formation to determine the ability of these novel scaffolds to promote vascularization of the injury site. The ultimate goal of this modular approach to tissue engineering is to incorporate therapeutic target molecules into morphologically relevant scaffold materials to recapitulate the temporal sequence of regenerative cues essential to enhancing muscle regeneration rather than volume loss or scar formation.

2. MATERIALS and METHODS

2.1. Microthread Preparation

2.1.1. Microthread Extrusion

Fibrin microthreads were co-extruded from solutions of fibrinogen and thrombin using extrusion techniques described previously [29, 31]. Briefly, fibrinogen from bovine plasma (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; F8630) was dissolved in HEPES (N-[2-Hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulfonic acid]) buffered saline (HBS, 20 mM HEPES, 0.9% NaCl; pH 7.4) at 70 mg/mL and stored at −20 °C until use. Thrombin from bovine plasma (Sigma; T4648) was dissolved in HBS at 40 U/mL and stored at −20 °C until use.

To fabricate microthreads, fibrinogen and thrombin solutions were thawed and warmed to room temperature, and thrombin was mixed with a 40 mM CaCl2 (Sigma) solution to form a working solution of 6 U/mL. Equal volumes of fibrinogen and thrombin/CaCl2 solutions were loaded into 1 mL syringes which were inserted into a blending applicator tip (Micromedics Inc., St. Paul, MN; SA-3670). The solutions were combined in the blending applicator and extruded through polyethylene tubing (BD, Sparks, MD) with an inner diameter of 0.86 mm into a bath of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) in a Teflon coated pan at a rate of 0.225 mL/min using a dual syringe pump. After 10 minutes, 25.4 cm amorphous fibrin microthreads were removed from the buffer solution and stretched to form three-19-cm microthreads and air dried under the tension of their own weight. Dry threads were placed in aluminum foil and stored in a desiccator until use.

2.1.2. Fibrin Microthread Crosslinking

Fibrin microthreads were crosslinked using techniques described previously [31]. Briefly, to create microthreads crosslinked in a neutral pH buffer (EDCn), microthreads were hydrated in monosodium phosphate buffer (100 mM NaH2PO4, Sigma, pH 7.4) for 30 minutes and then crosslinked monosodium phosphate or neutral buffer containing 16 mM N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, Sigma) and 28 mM 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC, Sigma) for 2 hours at room temperature. After crosslinking, the buffered EDC/NHS solution was aspirated and the microthreads were rinsed three times in a de-ionized (DI) water bath, air dried, sterilized with ethylene oxide, and stored in a desiccator until use.

2.1.3. Adsorption of HGF to Microthreads

Three uncrosslinked (UNX) or EDCn microthreads were attached onto polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, inner diameter 0.75 in., Dow Corning, Midland, MI) rings, sterilized with 70% ethanol for 90 minutes, rinsed with DI water three times, and air dried in a laminar flow hood overnight. Sterile microthread-PDMS constructs were hydrated in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) and the PDMS surfaces were blocked with 0.25% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma) for 1 hour. These solutions were aspirated and replaced with 1 mL of 40 ng/mL or 100 ng/mL of HGF (Peprotech, Rockyhill, NJ) in DPBS and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. The microthreads were rinsed three times in DPBS, twice in L-15 (Mediatech, Inc., Manassus, VA) and immediately used for implantations.

2.2. Cell Culture and Release of Active HGF from Microthreads

Immortalized mouse myoblasts (C2C12, ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio of high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and Ham’s F12 (Gibco) supplemented with 4 mM L-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, HyClone, Logan, UT). Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and maintained at a density below 70% confluence using standard cell culture techniques. Routine cell passage was conducted using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (CellGro, Manassas, VA).

To quantify the release of active HGF as a function of time, HGF-loaded microthreads (0, 40, or 100 ng/mL HGF) were attached to PDMS rings (3 threads per ring), and they were incubated in 1 mL of serum-free medium (SFM, 1:1 v/v high glucose DMEM/F-12) for a period of 96 hours. After 24, 48, or 96 hours, two 0.5 mL aliquots of conditioned-SFM (C-SFM) were removed and incubated on C2C12 myoblasts to determine the ability of the C-SFM to induce myoblast proliferation. Myoblasts were seeded in 24 well plates at a density of 10,000 cell/well and incubated in SFM for 4 hours prior to incubation with C-SFM to maintain a uniform cell population for each experiment. As negative or positive controls, myoblasts were cultured in SFM containing either 0 or 5 ng/mL of soluble HGF, respectively. Each experimental condition was run in triplicate. After an incubation time of 4 hours in C-SFM, cells were fixed with ice cold methanol, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma), immunostained with a primary antibody against Ki67 (1:400, rabbit polyclonal, D3B5; Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) and an Alexafluor 568 secondary (1:200, goat anti-rabbit, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), then counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (1:6000, Molecular Probes). To determine the percentage of proliferating cells, five images were taken of each well with a Zeiss inverted microscope and the number of Ki67 positive nuclei were normalized to the total number of nuclei counted in each image.

2.3. Animals and Surgical Procedures

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Female nude severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID) hairless outbred mice (Strain SHO, aged 7–8 weeks; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized with an i.p. injection of ketamine/xylazine (50/5 mg/kg), and all surgical procedures were performed under a stereo microscope as previously described [30]. The skin flap and fascia covering the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle was retracted and pre-injury contractile force values were measured. A critical sized defect was created in the central region of the muscle by resecting approximately 30 mg (4 × 2 × 2 mm) of tissue. The severity of each injury was assessed by measuring the force produced by single electrical impulses (twitch force) compared to pre-injury values measured immediately after tissue resection. Additional tissue was resected until the force reduction reached 50% for each animal, without significantly increasing defect dimensions. After the formation of the injury, one of five treatments were implanted into the injury site: no intervention, fibrin gel, UNX microthreads, EDCn microthreads, or EDCn-HGF microthreads. Fibrin gel implants were created by dropwise addition of sterile-filtered fibrinogen (70 mg/mL) into the injury site until it was full followed by a single drop of sterile-filtered thrombin (6 U/mL). Fibrin gels served as a material control to the injury site to uncouple the role of the fibrin microthread architecture from the bulk fibrin biomaterial for inducing organized, functional muscle regeneration. On average, 8–15 microthreads were used to completely fill the injury site. After implantation, microthreads were secured in the wound site using sequential drops of sterile fibrinogen and thrombin solutions. The muscle was kept hydrated during the procedure using sterile saline. The skin flap was replaced over the wound and secured with 8-0 SecurosOrb suture with TG140-8 needles (Cat No. 008170; Securos, Fiskdale, MA). Animals were allowed to recover under a heat lamp, administered 0.05 mg/kg buprenorphine every 12 hours for 72 hours for post-op care, and were allowed to move freely in individual cages. A total of 3 animals per treatment were used for analysis at 14 days post-injury, and 6 animals per treatment for analysis at 60 days post-injury. At the indicated times, animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. The body weight of each animal was recorded before surgery and before euthanization, and no significant changes in weight were noted at any time point (Table 1).

Table 1.

Animal weight and the dimensions of the injury site at 14 and 60 days post-injury.

| No Intervention | Fibrin Gel | UNX Microthreads | EDCn Microthreads | EDCn-HGF Microthreads | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 Days | 60 Days | 14 Days | 60 Days | 14 Days | 60 Days | 14 Days | 60 Days | 14 Days | 60 Days | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Sample Size (n) | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Body weight at surgery (g) | 25.2 ± 0.5 | 25.2 ± 0.5 | 24.9 ± 0.6 | 24.9 ± 0.6 | 24.7 ± 0.4 | 24.7 ± 0.4 | 24.3 ± 0.6 | 24.3 ± 0.6 | 24.0 ± 0.7 | 24.0 ± 0.7 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Body weight at sacrifice (g) | 26.3 ± 1.2 | 27.0 ± 1.1 | 24.3 ± 0.7 | 27.0 ± 0.7 | 24.7 ± 0.3 | 27.3 ± 0.8 | 25.3 ± 0.9 | 27.3 ± 0.8 | 25.7 ± 0.7 | 26.2 ± 0.9 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Defect Length (mm) | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.2* | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.2* | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2* |

|

| ||||||||||

| Defect Width (mm) | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.07 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 0.7 ± 0.06 | 0.3 ± 0.04* | 0.7 ± 0.11 | 0.2 ± 0.02* | 0.5 ± 0.10 | 0.2 ± 0.05* |

indicate significance with 14 day post-injury measurements as determined by Student’s t-test (p<0.05).

2.4. Contractile Force Measurements

To measure the muscle strength recovered by the implants, the contractile force evaluated for animals before injury (baseline), after injury, and at the time of sacrifice in situ, as previously described [30]. Briefly, the knee joint was anchored using a custom clamping system fixed to the floor of the stereomicroscope stand. A silk ligature was secured in the cleft between digits 1 and 3 of the mouse paw and was anchored to a force transducer (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) on the other end. The exposed TA muscle was stimulated using 2 custom needle electrodes placed on the proximal surface of the muscle. Electrical stimulation was applied at 4 V with a 4 ms pulse duration at 500 ms intervals and the resultant twitch forces (g) were recorded at a rate of 200 Hz using a BioPac MP-100 (BIOPAC Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA) and accompanying software (Acknowledge™, BIOPAC Systems, Inc.). Maximum force produced at tetanus was measured by reducing the pulse intervals to 20 ms. The twitch force and maximum force at tetanus were measured for the contralateral leg 60 days post-injury before euthanization for histological and immunohistochemical analysis. To account for variation in the amount of regeneration between animals, the isometric twitch force was normalized to the corresponding force measurement taken after the creation of the injury. At least fifteen contraction measurements per animal per time point were made.

2.5. Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis

Animals were euthanized at either 14 or 60 days post-injury and the TA muscle was exposed and dissected longitudinally away from the tibia leaving both ends affixed. The shape of the muscle as well as the gross morphology of the wound site was recorded, and the approximate wound site was marked with a histology pen. The whole lower leg was placed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 1 hr, after which the TA muscle was removed from the rest of the lower leg and fixed for an additional 2 hr at room temperature. Tissue was rinsed in PBS three times, bisected with a razor blade along the center of the wound site, and stored in 70% ethanol until processing and paraffin embedding. Muscle sections were embedded to visualize a lateral top-down view of the coronal plane of the muscle, revealing regeneration events as a function of tissue width. Serial 5 μm sections were cut, mounted on Superfrost Plus slides (VWR, West Chester, PA), and used for histological and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses. Slides stained with Masson’s trichrome to histologically characterize the tissue and determine the amount of fibrosis. Masson’s trichrome stains cytoplasm (muscle) and fibrin structures in red, collagen and connective tissue in blue, and nuclei in black, and staining was prepared using at least two sections 50 μm apart per animal using standard procedures.

Serial 5 μm sections were stained to visualize myogenin positive nuclei (myotubes) and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM; CD-31; blood vessels), respectively. For all staining, sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a series of graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was conducted in a pressure cooker for 20 min using a citrate-based antigen retrieval solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA; H-3300). The samples were allowed to cool to room temperature and rinsed with PBS. Each section was incubated for 30 min in a blocking solution of 2.5% horse serum in a humidified chamber. Sections were stained separately using antibodies targeting myogenin (Abcam; ab1835) at a 1:100 dilution or PECAM (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; ab28364) at a dilution of 1:50 in PBS/0.05% Tween for 45 min at room temperature. After 2 rinses of PBS/Tween, slides were incubated in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min to inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity. The slides were rinsed twice in PBS and incubated in the appropriate Impress horseradish peroxidase-based secondary antibody (anti-mouse IgG (Vector; MP7402) for myogenin, anti-rabbit IgG for PECAM (Vector; MP7401)) for 30 min at room temperature. An Impact DAB kit (Vector; SK-4105) was used to develop positive staining due to the presence of the Impress secondary antibody. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through graded alcohols and xylenes, and cover-slipped for analysis. Histology and IHC images were observed on a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Nikon, Inc., Melville, NY) coupled with a RT Color Spot camera (Spot Diagnostics, Sterling Heights, MI) with matching software. Quantitative histologic analyses were performed in a double-blinded fashion.

2.6. Estimation of Wound Size

To approximate the change in the wound size over time, the defect width and length were measured from multiple images that were acquired from slides stained with Masson’s trichrome with a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope using a 10X objective and stitched together using Adobe Photoshop CD5.1 (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Images were imported into ImageJ (NIH) and the length and width of the defect region were measured.

2.7. Collagen Quantification

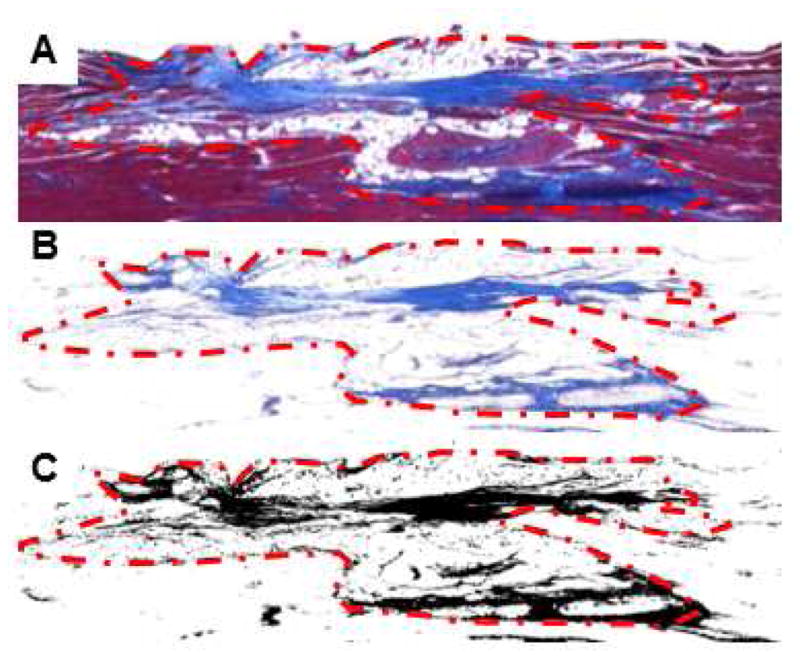

Collagen quantification was performed digitally by analyzing the entire defect site of Masson’s trichrome stained tissue sections (Figure 1A). Collagen pixel red green blue (RGB) values were recorded at 4–6 points in each of 15 images to obtain an average pixel RGB value to identify collagen content in Masson’s trichrome images. All the blue pixels per image were selected using this average RGB value using the Select > Color Range function with a “fuzziness” value of 92 in Photoshop (Figure 1B). The fuzziness value was empirically selected by averaging the same value for 15 randomly selected images, and functions as a threshold value to include varying RGB values of collagen. The resulting image was imported into ImageJ, thresholded, and analyzed for percent area of black pixels (i.e. collagen content) normalized to the total area per image comprised of muscle tissue (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Analysis of the percent collagen content within VML defect sites 60 days post-injury. (A) Composite images from the injury site were stained with Masson’s trichrome, and then (B) the blue pixels were selected in imaging software. (C) These images were thresholded to analyze for the percent area of collagen pixels.

2.8. Statistical Analyses

The data are reported as mean ± standard error. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Holm-Sidak pairwise multiple comparison test for post-hoc analysis using SigmaPlot 11.0 software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA). Where indicated, a paired Student’s t-test was performed. For all analyses, differences between conditions were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Rapid, Sustained Release of HGF Restores Mechanical Function after VML Injuries

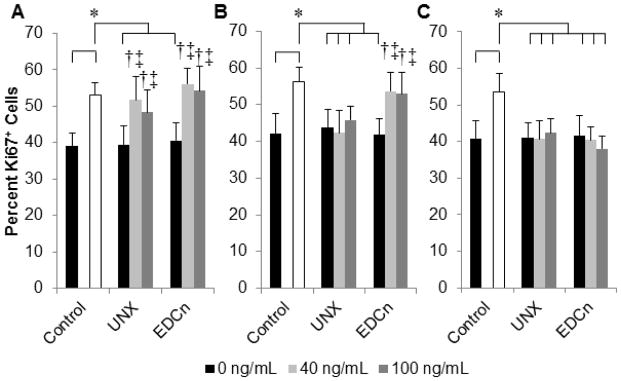

To quantitatively evaluate the temporal release activity of HGF from microthreads, myoblasts were incubated in serum-free medium conditioned with HGF-adsorbed microthreads (C-SFM) and cells were assayed for increases in proliferation by measuring Ki67 expression. The percent of Ki67 positive myoblasts significantly increased when the cells were cultured in SFM conditioned with HGF coated EDCn or HGF coated UNX microthreads for 24 hours (Figure 2A). This response is comparable to the response observed when cells were cultured in the presence of 5 ng/mL of soluble HGF, which is in the range of HGF concentrations found in the literature to maximally stimulate proliferation in myoblast populations [32]. HGF coated EDCn microthread C-SFM from 48 hr incubations also stimulated myoblast proliferation (Figure 2B); however, by 96 hrs C-SFM did not appear to significantly affect myoblast proliferation (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Characterization of the temporal release of active HGF from fibrin microthreads. Percentage of proliferative, Ki67 positive, C2C12 myoblasts is increased by serum free medium (SFM) conditioned with HGF-loaded fibrin microthreads, as a function of HGF concentration and time. Cell proliferation rates are compared to control SFM (0 ng/mL, black bars) and SFM supplemented with 5 ng/mL HGF (positive control, white bar). Conditioned media from (A) 0–24hrs, (B) 24–48 hrs, and (C) 72–96 hrs were analyzed. † indicate statistical significance with the negative control, ‡ indicate statistical significance with the 0 ng/mL of the same thread treatment group, and * represent statistical significance with the indicated groups as determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis (p>0.05, n≥2).

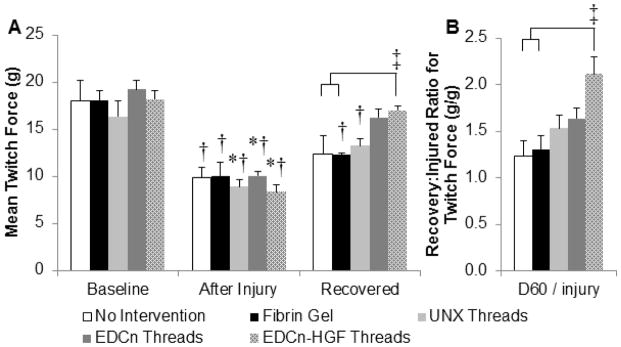

To quantify the amount of functional recovery in mice from acellular fibrin microthread implants, each critically-sized injury was created such that there was a 50% reduction in isometric twitch force from pre-injured, baseline values (Figure 3A). All microthread implants supported significantly higher twitch (Figure 3A) and tetanic (Table 2) forces 60 days post-injury than those generated immediately after injury. The recovered twitch forces from EDCn-HGF microthread implants were significantly stronger than untreated control or fibrin gel implant groups, and the absolute value of both the twitch and tetanic forces measured 60 days post-injury are similar to the healthy, baseline force values. The recovered forces resulting from fibrin gel or UNX microthread implants were significantly lower than their original baseline values. To account for possible variations in injured force measurements between animals, the recovered force of each animal was normalized to its own after injury measurement. This shows a percent recovery based upon the injured values, where any ratio above 1 (100%) would indicate an increase in the force output from injured values. There was an approximate 150% increase in force production from injured values for UNX and EDCn microthread implant treatments, and there was an increase of over 200% in both the twitch force production and the force at tetanus of animals that received EDCn-HGF microthread implants (Figure 3B). A summary of the results from all of the force measurements is presented in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Isometric twitch force of TA muscles before and after the creation of VML defects. (A) The isometric twitch force of TA muscles before injury, immediately after injury, and 60 days post-injury (recovered). (B) The amount of functional recovery normalized for the increase in regeneration in each individual animal. * indicates significant difference from recovered twitch forces, † indicate significant difference from baseline twitch forces, and brackets and ‡ indicate significant differences with indicated groups as determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis (p<0.05, n=6).

Table 2.

Summary of the functional characteristics TA muscles before and immediately after the generation of a VML defect, and 60 days post-injury.

| No Intervention | Fibrin Gel | UNX Microthreads | EDCn Microthreads | EDCn-HGF Microthreads | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Sample Size (n) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

|

| |||||

| Body weight at surgery (g) | 25.2 ± 0.5 | 24.9 ± 0.6 | 24.7 ± 0.4 | 24.3 ± 0.6 | 24.0 ± 0.7 |

|

| |||||

| Body weight at sacrifice (g) | 27.0 ± 1.1 | 27.0 ± 0.7 | 27.3 ± 0.8 | 27.3 ± 0.8 | 26.2 ± 0.9 |

| Isometric twitch force | |||||

| Baseline (g) | 18.1 ± 2.2† | 18.3 ± 0.9† | 16.3 ± 1.6† | 19.2 ± 1.0† | 18.2 ± 0.9† |

|

| |||||

| After Injury (g) | 9.9 ± 1.1 | 10.2 ± 1.4 | 8.9 ± 0.7 * | 10.0 ± 0.5 * | 8.3 ± 0.7 * |

|

| |||||

| Recovered (g) | 12.4 ± 2.0a | 12.3 ± 0.2†a | 13.3 ± 0.8† | 16.2 ± 0.9 | 17.0 ± 0.5 |

|

| |||||

| Contralateral (g) | 17.8 ± 1.2 | 18.7 ± 0.8 | 18.4 ± 0.5 | 19.4 ± 1.4 | 18.7 ± 0.8 |

|

| |||||

| Recovery/After injury (g/g) | 1.23 ± 0.18a | 1.30 ± 0.15a | 1.53 ± 0.14 | 1.64 ± 0.11 | 2.11 ± 0.19 |

|

| |||||

| Recovery/Contralateral (g/g) | 0.70 ± 0.11 | 0.66 ± 0.02a | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.85 ± 0.06 | 0.91 ± 0.03 |

|

| |||||

| Recovery/Body weight (g/g body wt) | 0.45 ± 0.06ab | 0.46 ± 0.01a | 0.48 ± 0.02a | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 0.65 ± 0.03 |

| Force at tetanic contraction | |||||

| Baseline (g) | 35.5 ± 4.6† | 37.5 ± 3.0† | 37.3 ± 2.4† | 36.8 ± 2.0† | 36.0 ± 3.5† |

|

| |||||

| After Injury (g) | 24.7 ± 2.7 | 22.9 ± 1.1 * | 21.7 ± 1.5 * | 23.6 ± 2.1 * | 18.4 ± 1.8 * |

|

| |||||

| Recovered (g) | 28.3 ± 4.2 | 29.4 ± 1.0† | 32.2 ± 2.0 | 34.7 ± 2.3 | 35.6 ± 1.0 |

|

| |||||

| Contralateral (g) | 38.8 ± 2.7 | 39.2 ± 1.1 | 35.7 ± 2.6 | 36.1 ± 3.5 | 36.0 ± 1.1 |

|

| |||||

| Recovery/After injury (g/g) | 1.11 ± 0.10a | 1.30 ± 0.08a | 1.54 ± 0.18 | 1.51 ± 0.13 | 2.03 ± 0.21 |

|

| |||||

| Recovery/Contralateral (g/g) | 0.72 ± 0.09a | 0.75 ± 0.02 | 0.93 ± 0.09 | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 0.99 ± 0.03 |

|

| |||||

| Recovery/Body weight (g/g body wt) | 1.03 ± 0.13 | 1.09 ± 0.04 | 1.19 ± 0.09 | 1.27 ± 0.06 | 1.37 ± 0.06 |

indicate significance with recovered forces (60 days post-injury),

indicate significance with baseline forces,

indicate significance with EDCn-HGF microthread implants, and

indicate significance with EDCn microthread implants as determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis (p<0.05).

3.2. HGF Loaded EDCn Microthreads Enhance Skeletal Muscle Regeneration

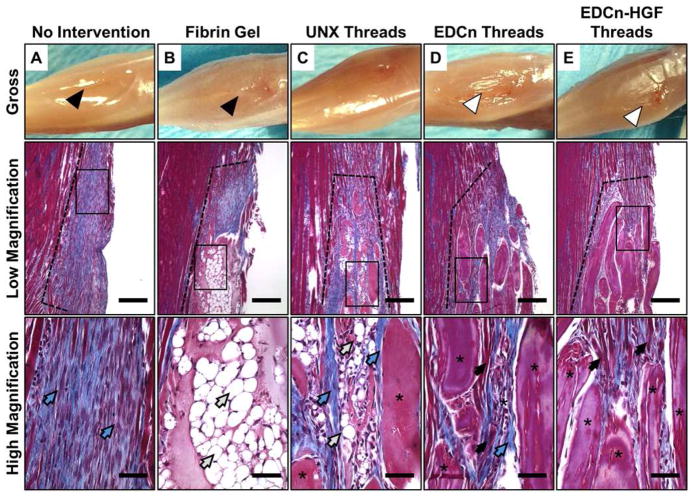

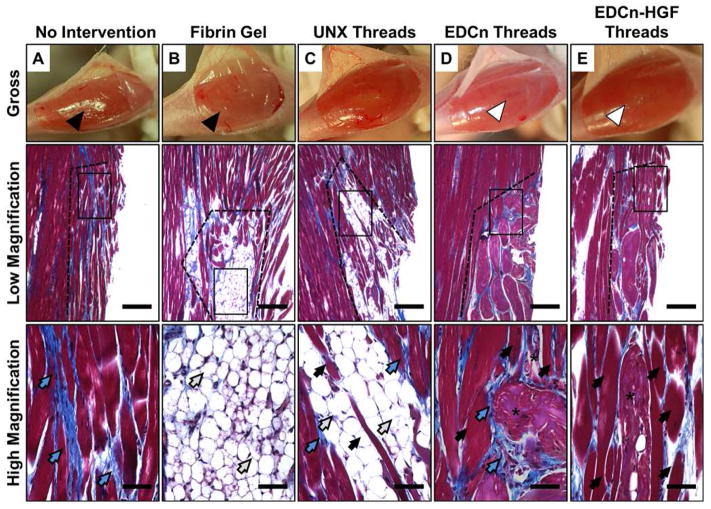

To investigate the role of fibrin microthreads in directing new tissue ingrowth and remodeling, we analyzed variations in skeletal muscle regeneration and organization as a function of time after implantation. Histological analyses of tissue morphology in the muscle defects 14 days post-injury showed the integration of the host tissue with each of the implants (Figure 4). EDCn (Figure 4D) and EDCn-HGF (Figure 4E) microthread implant groups exhibited a smooth, convex surface with no evidence of muscle loss as well as excellent tissue integration. Several myofibers (black arrows) were observed around, and between, discrete microthreads. EDCn-HGF microthread implants supported larger amounts of tissue ingrowth than EDCn microthread implants, and had less collagen deposition (blue arrows) at this time point. While there was more myoblast ingrowth into UNX microthread implants than fibrin gel implants 14 days post-injury, there was also adipocyte infiltration (white arrows) into the microthread structures, and collagen-like connective tissue was deposited around the microthread implants (Figure 4C). Untreated controls showed the most collagen fiber deposition, with few infiltrating myoblasts (Figure 4A). Fibrin gel implants persisted 14 days post-injury, and displayed poor integration with the host tissue. There was a paucity of myoblast infiltration or myofiber formation within the implant, but there were a large number of infiltrating adipocytes within the fibrin gel matrix (Figure 4B). Interestingly, there was evidence of a significant reduction in the muscle volume as early as 14 days post-injury in untreated and fibrin gel implant groups as shown by a loss of the convex shape of the surface of the muscle (Figure 4A–B).

Figure 4.

Morphology of the distal end of VML defect sites 14 days post-injury. Photographs showing the gross morphology as well as low (40X) and high (400X) magnification of Masson’s trichrome images of the coronal plane of VML defects with (A) no intervention, (B) fibrin gel implants, or (C) UNX, (D) EDCn, or (E) EDCn-HGF microthread implants. All defect sites are indicated by the black dotted line, and are surrounded by healthy muscle tissue. Black arrows indicate muscle growth, blue arrows indicate connective tissue and collagen, white arrows indicate adipose tissue, and asterisks indicate microthreads within the defect. Scale = 200 μm (low magnification) and 50 μm (high magnification).

EDCn-HGF and EDCn microthreads persisted through 60 days post-injury (asterisks) with minimal adipose infiltration (Figure 5D–E). Myofibers were observed in direct contact with EDCn-HGF microthreads, and this new tissue seems to be organized in plane with the surrounding healthy tissue (Figure 5E). Further, myofibers completely surrounded several EDCn-HGF microthreads aligned with the surrounding tissue, showing a remarkable amount of tissue ingrowth (Figure 5E). While both fibrin gel and UNX microthread implants supported extensive adipocyte infiltration (Figure 5B–C), UNX microthreads also remodeled into a combination of dense scar tissue and small myofibers that were visible within the fatty tissue (Figure 5C); however, these myofibers did not appear to be aligned with the surrounding healthy tissue. Sixty days post-injury, the loss of muscle volume persisted in untreated and fibrin gel implant groups (Figure 5A–B). Untreated injury sites remodeled to form disorganized myofibers that were surrounded by interstitial scar tissue (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Morphology of the distal end of VML defect sites 60 days post-injury. Photographs showing the gross morphology as well as low (40X) and high (400X) magnification of Masson’s trichrome images of the coronal plane of VML defects with (A) no intervention, (B) fibrin gel implants, or (C) UNX, (D) EDCn, or (E) EDCn-HGF microthread implants. All defect sites are indicated by the black dotted line, and are surrounded by healthy muscle tissue. Black arrows indicate muscle growth, blue arrows indicate connective tissue and collagen, white arrows indicate adipose tissue, and asterisks indicate microthreads within the defect. Scale = 200 μm (low magnification) and 50 μm (high magnification).

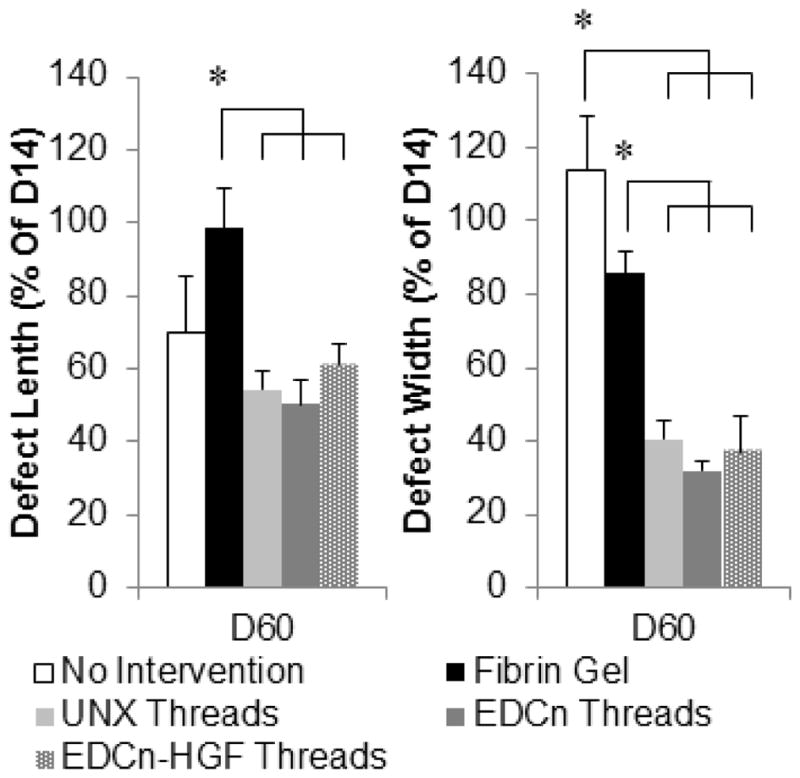

3.3. Fibrin Microthreads Reduce the Defect Size over Time, but do not Affect Collagen Deposition

To correlate our functional recovery results with the histological analyses, we quantified the changes in the length and width of the injury site as a function of time. The dimensions of injury sites from microthread implant groups (UNX, EDCn, and EDCn-HGF microthreads) were qualitatively larger than the respective injury sites for untreated and fibrin gel implant groups 14 days post-injury; however, all of the measurements were similar 60 days post-injury. Both dimensions of microthread implant injury sites significantly decreased from 14 to 60 days post-injury (Table 1). Measurements taken 60 days post-injury were normalized against taken 14 days post-injury to determine the reduction in each dimension over time. Interestingly, the decrease of the defect length for each microthread implant was significantly higher than that for fibrin gel implants (Figure 6). Similarly, the percent of defect width remaining from 14 days post-injury for each microthread group was significantly lower than the percent change for both the untreated and fibrin gel implant groups. These data suggest that microthread implant groups are facilitating an increase in tissue ingrowth and remodeling.

Figure 6.

Change in muscle defect length and width from 14 to 60 days post-injury. * indicate significance with indicated groups as determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis (p<0.05, n=6).

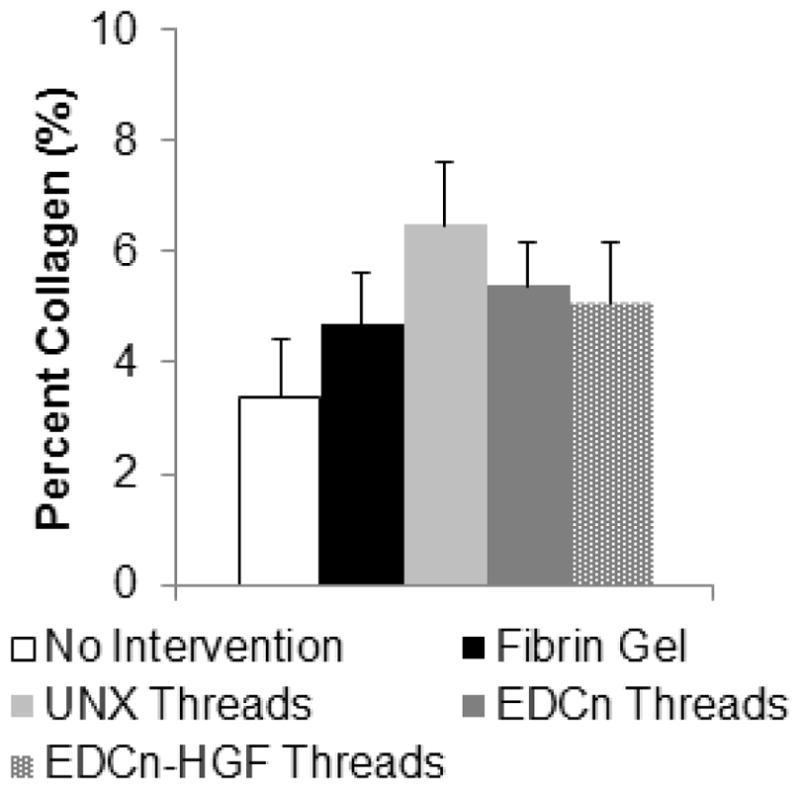

To determine the amount of scarring from VML injuries, we used digital image analyses of Masson’s trichrome stained sections to measure the percent of collagen tissue present in the defect site at 60 days post-injury (Figure 1A–C). There was not a significant increase in the percent of collagen tissue present in the defect site; however, there was no statistical significance between these measurements (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Percent collagen content within VML defect sites 60 days post-injury. No significant differences detected by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis (p<0.05, n=6).

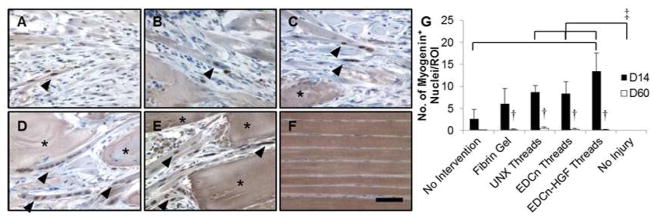

3.4. HGF Delivery Increases Number of Differentiating Myoblasts

To determine the number of nascent myofibers forming within the VML defect, tissue sections were immunostained for myogenin at 14 and 60 days post-injury. Myogenin positive nuclei were found in all implant groups 14 days post-injury, however, the number of multinucleated myofibers increased with the presence of microthread implants (Figure 8). Myofibers were located immediately adjacent to several crosslinked microthreads, indicating that these scaffold materials guided myoblast ingrowth into defect sites (Figure 8D–E). Further, the myofibers adjacent to crosslinked microthreads appeared to have more nuclei per multinucleated cell, suggesting an increase in the maturity of these nascent myofibers. As expected, no positive nuclei were observed in uninjured tissue (Figure 8F). All microthread implants 14 days post-injury supported significantly more myogenin positive nuclei than uninjured tissue, and EDCn-HGF microthreads supported significantly more myogenin positive nuclei than untreated controls (Figure 8G). The number of myogenin positive nuclei in the implant groups significantly decreased from 14 to 60 days post-injury (Figure 8G). In fact, little to no myogenin positive nuclei were identified 60 days post-injury for any treatment group, suggesting that myoblasts were no longer fusing into myotubes and that the differentiation phase of skeletal muscle regeneration had resolved at this time.

Figure 8.

IHC staining of myogenin positive nuclei in VML defects 14 days post-injury. IHC staining for myogenin with a hemotoxylin counterstain of VML defects with (A) no intervention, (B) fibrin gel, (C) UNX microthreads, (D) EDCn microthreads, (E) EDCn-HGF microthreads, or (F) uninjured muscle. Asterisks indicate microthreads and black arrowheads denote representative myogenin positive nuclei. Scale = 50 μm. (G) Quantification of the number of myogenin positive nuclei in VML defects. ‡ and brackets indicate significant differences between indicated groups as determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis, † denote significance with D14 values as determined by Student’s t-test (p<0.05, n=3 for D14, n=6 for D60).

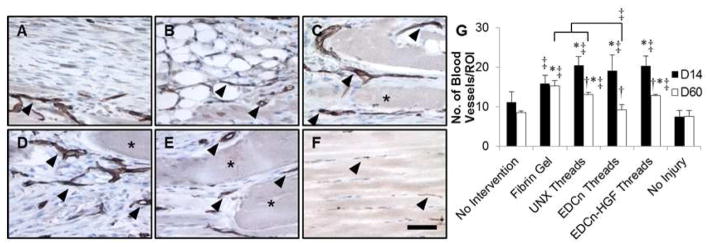

3.5. HGF Induces Sustained Angiogenesis in VML Defects

To determine ability of EDCn-HGF microthreads to support blood vessel infiltration into injury site, tissue sections were immunostained for PECAM (CD31). PECAM is a protein found on the surface of endothelial cells, and it is used to identify blood vessels within a defect site. Blood vessels were located in all defect sites 14 days post-injury (Figure 9) except untreated controls, where the connective tissue within the injury site appeared to be avascular (Figure 9A). Blood vessels formed a capillary network around adipocytes that infiltrated the fibrin gel and UNX microthread implants (Figure 9B–C). Interestingly, while there was no evidence of adipogenic infiltration into EDCn and EDCn-HGF microthread implants, blood vessels were identified between and adjacent to EDCn-HGF microthreads within the injury site (Figure 9D–E). Significantly more blood vessels formed in microthread implant injury sites than untreated and uninjured tissues 14 days post-injury. The fibrin gel implant group had significantly higher numbers of blood vessels in the injury site than uninjured controls (Figure 9G). Sixty days post-injury, there were fewer blood vessels present than 14 days post-injury in all defect sites. All microthread implants had significantly fewer blood vessels present in the defect site at 60 days post-injury with respect to 14 days post injury (Figure 9G). Importantly, the number of blood vessels remained elevated for EDCn-HGF microthread implant groups with respect to the untreated and uninjured control groups, suggesting that a sustained increase in the vascularization of these tissues may have facilitated tissue regeneration (Figure 9G). An elevated number of blood vessels remained within the wound sites of fibrin gel, and the UNX microthread implant groups, likely due to the dense capillary network required for adipose tissue.

Figure 9.

IHC staining of PECAM in VML defects 14 days post-injury. IHC staining for PECAM with a hemotoxylin counterstain of VML defects with (A) no intervention, (B) fibrin gel, (C) UNX microthreads, (D) EDCn microthreads, (E) EDCn-HGF microthreads, or (F) uninjured muscle. Asterisks indicate microthreads and black arrowheads denote representative blood vessels. Scale = 50 μm. (G) Quantification of the number of PECAM positive blood vessels in VML defects. ‡ and brackets indicate significant differences between indicated groups as determined by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak post hoc analysis, † denote significance with D14 values as determined by Student’s t-test (p<0.05, n=3 for D14, n=6 for D60).

4. DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to investigate the ability of EDCn-HGF microthreads to enhance functional regeneration in a mouse model of VML. EDCn-HGF microthreads significantly increased the force production of regenerated skeletal muscle tissue VML injuries sites to values that were comparable to pre-injury baseline forces, likely as a result of increased SC recruitment. VML injuries typically result from traumatic incidents, often requiring immediate surgical intervention to stabilize patients. Acellular scaffold materials are promising solutions for these indications, because they are readily available for implantation, while cell based skeletal muscle units can take several weeks to months to prepare, slowing the time to surgical intervention [33, 34]. At present, acellular scaffolds, such as decellularized ECM and gelatin gels, have not demonstrated an ability to stimulate functional improvement in VML injuries [22, 26, 35]. This could be a result of the preparation of decellularized ECM materials, since reagents used in the decellularization process can dramatically alter the bioactivity of proteins or growth factors in the biomatrix [36, 37]. Our approach to the design and fabrication of scaffolding materials is a “bottom-up” approach, where materials are systematically added to a scaffold to direct specific regenerative cell functions. For the first time, we describe a process to adsorb HGF to the surface of fibrin microthreads. Our results indicate that the combination of an EDC-crosslinked microthread with rapid delivery of HGF to the injury site will direct significant tissue regeneration, and functional recovery of TA muscle defects.

All microthread implant groups increased the force production of the TA muscle by at least 150% from force measurements made immediately after injury. EDCn and EDCn-HGF microthread implants were the only treatment groups that consistently supported enough functional remodeling to produce forces comparable to baseline values measured before the induction of the VML injury. Further, EDCn-HGF microthreads increased the force production of TA muscles 200% with respect to injured values. The promotion of significant functional recovery within 2 months post-injury supports our hypothesis that HGF delivery to VML injury sites will enhance the functional recovery of VML injuries. Our findings differ from the results of studies conducted with scaffold materials that were unable to produce any functional recovery within this time scale [26, 35, 38, 39]. Other studies indicate that acellular decellularized ECM materials promote functional recovery approximately 6 months post-injury, although it was not clear whether this delay in functional recovery was a result of the difference in the animal model and the resultant injury site being two- to three-fold larger than the one presented in this study [19, 24, 25, 40]. However, similarly sized injuries to the one presented in this study also did not report significant functional recovery within 2 months post-injury [18, 35]. We attribute the successful functional regeneration of muscle tissue to the synergistic effects of the morphologic structure of our scaffolds, as well as the rapid delivery of HGF to the injury site.

One of the most critical functions of scaffolds in skeletal muscle regeneration is that they must direct myoblast differentiation in the same plane as the adjacent healthy skeletal muscle tissue. Fibrin microthreads have been shown to direct cell alignment along the length of the fibers [29], and we extended their in vitro lifetime to direct long term tissue regeneration [31]. Remarkably, myofibers were observed in direct contact with EDCn and EDCn-HGF microthreads, in some cases completely surrounding EDCn-HGF microthreads. This finding supports our hypothesis that microthreads with increased resistance to proteolytic degradation would enhance skeletal muscle tissue regeneration. These new myofibers were all aligned with the healthy tissue, suggesting that they are responsible for the functional improvements observed in this study. However, it cannot be ruled out that some degree of the functional recovery could be due to hypertrophic compensation from non-injured tissue adjacent to the injury site, perhaps mediated by HGF release from the EDCn fibrin microthreads. We were surprised to observe the persistence of EDCn microthreads in the wound site 60 days post-injury. Others have indicated that long-term remodeling may be advantageous for the recovery of VML injuries with acellular implants [24]. Future studies will elucidate the degradation time of EDCn microthreads in skeletal muscle and define the results of long-term remodeling due to these materials.

The delivery of HGF had a remarkable effect on the functional regeneration of our model of VML. In native tissue, HGF is released from the ECM of muscle injuries to recruit and activate SCs, which proliferate within the injury site and eventually differentiate into myoblasts and myofibers, regenerating the injured tissue. We identified significantly more myogenin positive nuclei in the injury site of EDCn-HGF microthread implants than untreated or uninjured controls. These nascent myofibers were in direct contact with EDCn and EDCn-HGF microthreads, suggesting that the HGF-mediated recruitment by EDCn-HGF implants occurred before 14 days. This is consistent with our in vitro data for the HGF release profile measured from EDCn microthreads, showing that active release of HGF occurs for 2–4 days. Interestingly, active release only occurred on UNX threads within the first day, suggesting that this material would not serve as an appropriate HGF delivery vehicle for functional regeneration in vivo. We hypothesize that our HGF loading strategy on EDCn microthreads increased the amount of SCs present in the injury site at an earlier time similar to the native recruitment of SCs to muscle injuries [22, 41]. This earlier recruitment would facilitate a subsequent increase in the number of differentiating myoblasts, explaining the significant increase in myogenin positive nuclei observed in EDCn-HGF microthread implants 14 days post-injury. The characterization of SCs within the implantation site at earlier time points, such as 4 days, will be the subject of future studies.

An unexpected finding in this study was that UNX microthread and fibrin gel implants invoked a robust infiltration of adipocytes. This response is characteristic of a clinical pathology known as fatty degeneration, and has been observed in a variety of muscle wounds including rotator cuff tears [42–44]. Adipogenic infiltration has been observed in several other models of VML, showing that the environment presented by acellular scaffolds might encourage this pathological condition [24, 25, 45]. While the origin of the adipocytes remains in question, some reports suggest they might arise from a population of pericytes, progenitor cells residing in skeletal muscle that are found in close proximity to blood vessels [42, 46]. Mesenchymal progenitors expressing platelet derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα) were also found to contribute to adipose formation in skeletal muscle; however, the environment of healthy skeletal muscle tissue was able to reverse this adipogenesis [47, 48]. Interestingly, adipocytes were only found within the structure of the fibrin gel and UNX microthreads 14 days post-injury. This suggests that the unique biochemical and mechanical environment within the uncrosslinked fibrin may be facilitating the recruitment of adipocytes. While this might seem to suggest that recruited SCs would be transdifferentiating into adipocytes on UNX microthreads, recent studies demonstrate that SCs are committed to the myogenic lineage and do not spontaneously transdifferentiate [49]. An alternate hypothesis is that the mechanical and biochemical environment within these fibrin matrices is recruiting adipogenic cells, although the source of these progenitor cells is equivocal. In contrast, EDCn microthreads, which have stiffness values that are twofold greater than UNX microthreads [31], and are comparable to contracting muscle [50], do not appear to recruit adipogenic cells. It is possible that in this model of VML, fatty infiltration is mediated by a stiffness mismatch between the implanted material and skeletal muscle tissue; however, the mechanisms behind the cause and development of fatty infiltration or fatty degeneration are not known at this time. Future studies involving UNX microthread and fibrin gel implants may be able to create a model for fatty infiltration or fatty degeneration in muscle tissue to answer these mechanistic questions.

Rather than remodel into a massive scar, we observed a distinct loss of muscle volume from our gross morphologic assessments of the shape of the TA muscle, secondary to a VML injury. Interestingly, while there was a significant amount of interstitial collagen present in untreated controls, there were no significant differences in the total amount of collagen present in the entire wound site of any treatment group. This loss of volume is typical of VML injuries, and has been seen in clinical cases of VML, validating our animal model and wound size [51–53]. Importantly, only untreated and fibrin gel implant groups resulted in this loss of volume despite the generation of similarly sized injuries. The dimensions of the injury sites with microthread implants were twice as large as their corresponding measurements in untreated and fibrin gel implant groups, corroborating our gross morphological observations. This suggests that fibrin microthreads stabilize the injury site and serve as a space filling material to prevent the loss of muscle volume, which can occur in as little as 14 days. Recent human clinical trials treating VML defects with decellularized ECM suggest that space-filling materials encourage endogenous remodeling to recover tissue loss [51]. Taken together, the reduction in the injury size along with an increase in functional recovery and regenerated muscular tissue suggests EDCn-HGF microthreads are directing the growth of new muscle tissue. Future studies will assess the ability of EDCn-HGF loaded microthreads to restore muscle volume and function in existing VML injuries and will examine the volume and weight of each TA muscle to more quantitatively determine tissue loss and recovery.

5. Conclusions

In summary, HGF-loaded EDCn microthreads improve the functional regeneration of skeletal muscle in a critically-sized injury, supporting significant functional regeneration of the TA muscle that approximates baseline values. In contrast, UNX microthreads appear to promote an adipogenic response. Finally, the release of HGF from EDCn-HGF microthreads significantly increased the number of differentiating myoblasts 14 days after injury and supported an enhanced angiogenic response at both 14 and 60 days after injury.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jason Forte, Jen Molignano, and Amanda Clement for their assistance with the collectio n of the force data during the surgical procedures. This research was funded in part by US Army (W81XWH-11-1-0631, G.D.P. and R.L.P.), NIH R01-HL115282 (G.D.P.), and NIH F31-DE023281 (J.M.G.).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

G.D.P. discloses that he is a co-founder and has an equity interest in Vitathreads L.L.C., a company that has licensed intellectual property associated with fibrin microthreads.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Owens BD, Kragh JF, Jr, Macaitis J, Svoboda SJ, Wenke JC. Characterization of extremity wounds in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. J Orthop Trauma. 2007;21:254–7. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31802f78fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owens BD, Kragh JF, Jr, Wenke JC, Macaitis J, Wade CE, Holcomb JB. Combat wounds in operation Iraqi Freedom and operation Enduring Freedom. J Trauma. 2008;64:295–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318163b875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heemskerk J, Kitslaar P. Acute compartment syndrome of the lower leg: retrospective study on prevalence, technique, and outcome of fasciotomies. World J Surg. 2003;27:744–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-6691-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckardt A, Fokas K. Microsurgical reconstruction in the head and neck region: an 18-year experience with 500 consecutive cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2003;31:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(03)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi B, Copelli C, Ferrari S, Ferri A, Sesenna E. Free flaps: outcomes and complications in head and neck reconstructions. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2009;37:438–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Floriano R, Peral B, Alvarez R, Verrier A. O.327 Microvascular free flaps in head and neck reconstruction. Report of 71 cases. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 2006;34:90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zammit PS, Partridge TA, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. The skeletal muscle satellite cell: the stem cell that came in from the cold. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1177–91. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6R6995.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan JE, Partridge TA. Muscle satellite cells. The International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2003;35:1151–6. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tatsumi R, Hattori A, Ikeuchi Y, Anderson JE, Allen RE. Release of hepatocyte growth factor from mechanically stretched skeletal muscle satellite cells and role of pH and nitric oxide. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2909–18. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tatsumi R, Liu X, Pulido A, Morales M, Sakata T, Dial S, et al. Satellite cell activation in stretched skeletal muscle and the role of nitric oxide and hepatocyte growth factor. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2006;290:C1487–94. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00513.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tatsumi R, Sheehan SM, Iwasaki H, Hattori A, Allen RE. Mechanical stretch induces activation of skeletal muscle satellite cells in vitro. Experimental cell research. 2001;267:107–14. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gal-Levi R, Leshem Y, Aoki S, Nakamura T, Halevy O. Hepatocyte growth factor plays a dual role in regulating skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation and differentiation. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1998;1402:39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(97)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatsumi R, Allen RE. Active hepatocyte growth factor is present in skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. Muscle & nerve. 2004;30:654–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.20114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatsumi R, Anderson JE, Nevoret CJ, Halevy O, Allen RE. HGF/SF is present in normal adult skeletal muscle and is capable of activating satellite cells. Dev Biol. 1998;194:114–28. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi S, Aso H, Watanabe K, Nara H, Rose MT, Ohwada S, et al. Sequence of IGF-I, IGF-II, and HGF expression in regenerating skeletal muscle. Histochemistry and cell biology. 2004;122:427–34. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0704-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller KJ, Thaloor D, Matteson S, Pavlath GK. Hepatocyte growth factor affects satellite cell activation and differentiation in regenerating skeletal muscle. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2000;278:174–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.1.C174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borselli C, Storrie H, Benesch-Lee F, Shvartsman D, Cezar C, Lichtman JW, et al. Functional muscle regeneration with combined delivery of angiogenesis and myogenesis factors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:3287–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903875106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sicari BM, Agrawal V, Siu BF, Medberry CJ, Dearth CL, Turner NJ, et al. A murine model of volumetric muscle loss and a regenerative medicine approach for tissue replacement. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:1941–8. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corona BT, Wu X, Ward CL, McDaniel JS, Rathbone CR, Walters TJ. The promotion of a functional fibrosis in skeletal muscle with volumetric muscle loss injury following the transplantation of muscle-ECM. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3324–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill E, Boontheekul T, Mooney DJ. Regulating activation of transplanted cells controls tissue regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:2494–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506004103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill E, Boontheekul T, Mooney DJ. Designing scaffolds to enhance transplanted myoblast survival and migration. Tissue engineering. 2006;12:1295–304. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ju YM, Atala A, Yoo JJ, Lee SJ. In situ regeneration of skeletal muscle tissue through host cell recruitment. Acta biomaterialia. 2014;10:4332–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen XK, Walters TJ. Muscle-derived decellularised extracellular matrix improves functional recovery in a rat latissimus dorsi muscle defect model. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery: JPRAS. 2013;66:1750–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valentin JE, Turner NJ, Gilbert TW, Badylak SF. Functional skeletal muscle formation with a biologic scaffold. Biomaterials. 2010;31:7475–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corona BT, Ward CL, Baker HB, Walters TJ, Christ GJ. Implantation of in vitro tissue engineered muscle repair constructs and bladder acellular matrices partially restore in vivo skeletal muscle function in a rat model of volumetric muscle loss injury. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:705–15. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merritt EK, Hammers DW, Tierney M, Suggs LJ, Walters TJ, Farrar RP. Functional assessment of skeletal muscle regeneration utilizing homologous extracellular matrix as scaffolding. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1395–405. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf MT, Daly KA, Brennan-Pierce EP, Johnson SA, Carruthers CA, D’Amore A, et al. A hydrogel derived from decellularized dermal extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 2012;33:7028–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolf MT, Daly KA, Reing JE, Badylak SF. Biologic scaffold composed of skeletal muscle extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2916–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornwell KG, Pins GD. Discrete crosslinked fibrin microthread scaffolds for tissue regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82:104–12. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Page RL, Malcuit C, Vilner L, Vojtic I, Shaw S, Hedblom E, et al. Restoration of skeletal muscle defects with adult human cells delivered on fibrin microthreads. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2629–40. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grasman JM, Page RL, Dominko T, Pins GD. Crosslinking strategies facilitate tunable structural properties of fibrin microthreads. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012;8:4020–30. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamada M, Tatsumi R, Yamanouchi K, Hosoyama T, Shiratsuchi S, Sato A, et al. High concentrations of HGF inhibit skeletal muscle satellite cell proliferation in vitro by inducing expression of myostatin: a possible mechanism for reestablishing satellite cell quiescence in vivo. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2010;298:C465–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00449.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mertens JP, Sugg KB, Lee JD, Larkin LM. Engineering muscle constructs for the creation of functional engineered musculoskeletal tissue. Regenerative medicine. 2014;9:89–100. doi: 10.2217/rme.13.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VanDusen KW, Syverud BC, Williams ML, Lee JD, Larkin LM. Engineered skeletal muscle units for repair of volumetric muscle loss in the tibialis anterior muscle of a rat. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:2920–30. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machingal MA, Corona BT, Walters TJ, Kesireddy V, Koval CN, Dannahower A, et al. A tissue-engineered muscle repair construct for functional restoration of an irrecoverable muscle injury in a murine model. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2291–303. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faulk DM, Carruthers CA, Warner HJ, Kramer CR, Reing JE, Zhang L, et al. The effect of detergents on the basement membrane complex of a biologic scaffold material. Acta biomaterialia. 2014;10:183–93. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuchiya T, Balestrini JL, Mendez J, Calle EA, Zhao L, Niklason LE. Influence of pH on extracellular matrix preservation during lung decellularization. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2014;20:1028–36. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2013.0492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merritt EK, Cannon MV, Hammers DW, Le LN, Gokhale R, Sarathy A, et al. Repair of traumatic skeletal muscle injury with bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells seeded on extracellular matrix. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2871–81. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gamba PG, Conconi MT, Lo Piccolo R, Zara G, Spinazzi R, Parnigotto PP. Experimental abdominal wall defect repaired with acellular matrix. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:327–31. doi: 10.1007/s00383-002-0849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conconi MT, De Coppi P, Bellini S, Zara G, Sabatti M, Marzaro M, et al. Homologous muscle acellular matrix seeded with autologous myoblasts as a tissue-engineering approach to abdominal wall-defect repair. Biomaterials. 2005;26:2567–74. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Mathew SJ, Hutcheson DA, Kardon G. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development. 2011;138:3625–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Mintz A, et al. Role of pericytes in skeletal muscle regeneration and fat accumulation. Stem Cells Dev. 2013;22:2298–314. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Itoigawa Y, Kishimoto KN, Sano H, Kaneko K, Itoi E. Molecular mechanism of fatty degeneration in rotator cuff muscle with tendon rupture. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:861–6. doi: 10.1002/jor.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim HM, Galatz LM, Lim C, Havlioglu N, Thomopoulos S. The effect of tear size and nerve injury on rotator cuff muscle fatty degeneration in a rodent animal model. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery/American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons [et al] 2012;21:847–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kin S, Hagiwara A, Nakase Y, Kuriu Y, Nakashima S, Yoshikawa T, et al. Regeneration of skeletal muscle using in situ tissue engineering on an acellular collagen sponge scaffold in a rabbit model. Asaio J. 2007;53:506–13. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3180d09d81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joe AW, Yi L, Natarajan A, Le Grand F, So L, Wang J, et al. Muscle injury activates resident fibro/adipogenic progenitors that facilitate myogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:153–63. doi: 10.1038/ncb2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Uezumi A, Fukada S, Yamamoto N, Takeda S, Tsuchida K. Mesenchymal progenitors distinct from satellite cells contribute to ectopic fat cell formation in skeletal muscle. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:143–52. doi: 10.1038/ncb2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wosczyna MN, Biswas AA, Cogswell CA, Goldhamer DJ. Multipotent progenitors resident in the skeletal muscle interstitium exhibit robust BMP-dependent osteogenic activity and mediate heterotopic ossification. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1004–17. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Starkey JD, Yamamoto M, Yamamoto S, Goldhamer DJ. Skeletal muscle satellite cells are committed to myogenesis and do not spontaneously adopt nonmyogenic fates. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:33–46. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.956995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caiozzo VJ. Plasticity of skeletal muscle phenotype: mechanical consequences. Muscle & nerve. 2002;26:740–68. doi: 10.1002/mus.10271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sicari BM, Rubin JP, Dearth CL, Wolf MT, Ambrosio F, Boninger M, et al. An acellular biologic scaffold promotes skeletal muscle formation in mice and humans with volumetric muscle loss. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:234ra58. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mase VJ, Jr, Hsu JR, Wolf SE, Wenke JC, Baer DG, Owens J, et al. Clinical application of an acellular biologic scaffold for surgical repair of a large, traumatic quadriceps femoris muscle defect. Orthopedics. 2010;33:511. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20100526-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garg K, Ward CL, Hurtgen BJ, Wilken JM, Stinner DJ, Wenke JC, et al. Volumetric muscle loss: Persistent functional deficits beyond frank loss of tissue. J Orthop Res. 2014 doi: 10.1002/jor.22730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]