Abstract

B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (B-LPD) is generally characterized by the proliferation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-infected B lymphocytes. We here report the development of EBV-negative B-LPD associated with EBV-reactivation following antithymocyte globulin (ATG) therapy in a patient with aplastic anemia. The molecular autopsy study showed the sparse EBV-infected clonal T cells could be critically involved in the pathogenesis of EBV-negative oligoclonal B-LPD through cytokine amplification and escape from T-cell surveillances attributable to ATG-based immunosuppressive therapy, leading to an extremely rare B-cell-rich T-cell lymphoma. This report helps in elucidating the complex pathophysiology of intractable B-LPD refractory to rituximab.

Key words: Lymphoproliferative disorder, Epstein-Barr virus, molecular autopsy, anti-thymocyte globulin, aplastic anemia

Introduction

Lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) in association with the reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has frequently been reported in immunocompromised patients following antithymocyte globulin (ATG) therapy.1,2 EBV is a ubiquitous human -herpesvirus found in virtually all adult populations worldwide.3-5 EBV commonly remains latent in naïve B cells; however, in rare circumstances, it has also been shown to infect T cells and natural killer (NK) cells.4,5 Cytotoxic lymphocytes generally control EBV infection.6,7 EBV is often reactivated in patients with immune dysfunction,8,9 leading to LPD and lymphoma.2,5,8-10 LPD associated with EBV-reactivation is often characterized by the proliferation of EBV-infected lymphocytes.2,8,10

The rationale for use of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab in EBV-associated LPD rests on the frequent expression of the CD20 B-cell antigen. Indeed, patients with EBV-associated B-LPD have been treated with rituximab with variable efficacy.11,12 However, patients with a large tumor burden of the B-LPD or following ATG therapy for idiopathic aplastic anemia (AA) and stem cell transplantation have had a particularly bad response to antibody therapy including rituximab and a poor survival.1,2,12,13 Bone marrow failure and therapy-induced immunocompromized conditions are also occasionally life-threatening due to severe infection including EBV-reactivation, hemorrhage, or delayed transformation and major causes of death.1,2,14,15 We herein described a patient with AA who developed EBV-negative oligoclonal B-LPD in association with both reactivated clonal EBV and clonal T cells following ATG therapy. The findings of this study may shed new light on the pathophysiology of intractable LPD.

Case Report

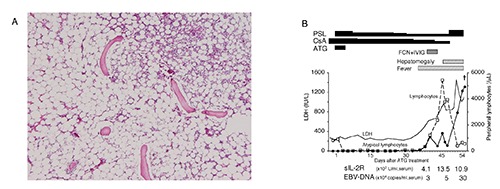

A 69-year-old woman with acquired AA was admitted for ATG-based immunosuppressive therapy. On admission, she did not exhibit any signs of lymphadenopathy or hepatomegaly. Laboratory tests are shown in Table 1. She had undergone total gastrectomy, partial pancreas head resection, and splenectomy for gastric cancer four years previously, and had been diagnosed with idiopathic AA based on findings such as hypoplastic fatty marrow (Figure 1A) with a normal karyotype in the absence of an abnormal infiltrate including lymphoid neoplasms, myelodysplasia, infections, or rheumatic diseases six months prior to her admission. She was treated initially with cicrosporin (CsA) and metenolone acetate, and subsequently with rabbit ATG, CsA, and prednisolone. The T-cell population of lymphocytes disappeared after the therapy (Figure 1B). She developed fever, hypoglycemia, and marked lymphocytosis with the reactivation of EBV and cytomegalovirus on day 54 after this treatment (Figure 1B). EBV-reactivation was confirmed by an increase in serum EBV-DNA (300×103 copies/mL) and the results of serological tests (positive for both IgG to the EBV capsid antigen and antibody to the EBV nuclear antigen). She also exhibited rapidly fatal complications associated with hepatomegaly, renal dysfunction, and an infection with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia prior to initiating treatment with rituximab (Table 1). Clinically, she was diagnosed with aggressive LPD and EBV-reactivation.

Table 1.

Laboratory data.

| Reference | On admission | 50th day | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocytes, μL | 3500-9800 | 2030 | 1790 |

| Neutrophils, μL | 1830-7250 | 1096 | 447 |

| Lymphocytes, μL | 1500-4000 | 812 | 411 |

| Atypical lymphocytes, μL | 0 | 0 | 877 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12-15 | 7.6 | 9.5 |

| Platelets, μL | 130,000-370,000 | 33,000 | 47,000 |

| Reticulocytes, μL | 8000-125,000 | 38,000 | 14,000 |

| Total protein, g/dL | 6.7-8.1 | 6.2 | 5.5 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.9-4.9 | 3.9 | 2.0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 7-38 | 17 | 651 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 4-44 | 19 | 129 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 106-220 | 268 | 1453 |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | |||

| Total | 0.2-1.2 | 0.6 | 9.9 |

| Direct | 0-0.2 | 0.1 | 8.1 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.43-0.72 | 1.38 | 2.21 |

| Amylase, U/L | 40-126 | 96 | 172 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | 0-0.3 | 0.07 | 23.02 |

| IL-2, U/mL | ≤0.8 | ND | 0.9 |

| IL-4, pg/mL | ≤6.0 | ND | 6.3 |

| IL-6, pg/mL | ≤4.0 | ND | 4130 |

| IL-10, pg/mL | ≤5 | ND | 8210 |

| IFNγ, U/mL | ≤0.1 | ND | 8.1 |

| TNFα, pg/mL | ≤5 | ND | 145 |

IFNγ, interferone ; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor ; ND, not determined.

Figure 1.

Severe aplastic anemia with aggressive LPD and EBV-reactivation. (A) Bone marrow biopsy showing markedly hypocellular marrow. (B) Immunosuppressive therapy, LPD, and EBV-proliferation. The T-cell population of lymphocytes disappeared after ATG therapy. PSL, prednisolone; CsA, ciclosporin; ATG, antithymocyte globulin; FCN, foscarnet; IVIG, intravenous injection of immunoglobulins; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; sIL-2R, soluble IL-2 receptor.

Results and Discussion

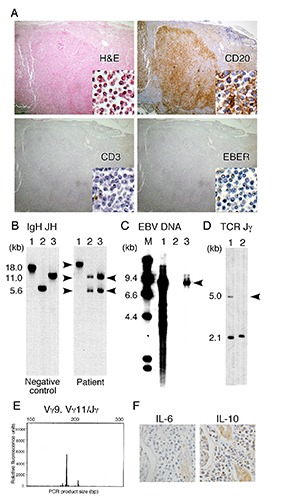

The present study gives a new insight into EBV-associated LPD through a rare AA patient undergoing ATG therapy and subsequently developing fatal LPD with autopsy analysis. Histological examinations revealed that lymphocytes densely infiltrated into the para-aortic lymph nodes (Figure 2A), liver, kidney, pancreas, and thyroid. Flow cytometry showed that most lymphocytes expressed pre-B-cell markers such as CD3-, CD7-, CD19+, CD20+, CD38+, and κ-chain+ (data not shown). Apparently, the LPD indicated EBV-associated B-LPD with EBV infection. However, of interest, the elaborate analyses showed that lymphocytes in the LPD lesions were oligoclonal when assessed by Southern blotting (Figure 2B) and the detection of two serum M-proteins (IgG and IgM). Predominant lymphocytes within the LPD lesions were also negative for EBER when limited by the presence of CD3- CD20+ B cells (inset right below for each panel in Figure 2A) and no major chromosomal abnormalities were detected (data not shown). Moreover, it did not affect the quantity of the two digested bands in Southern blotting for the IgH rearrangement (Figure 2B, lanes 2 and 3 of the patient) in spite of only a small minority of clonal EBV-positive cells. Thus, these results suggest that oligoclonally expanding EBV-negative B cells virtually occupied the LPD lesions.

Figure 2.

EBV-negative oligoclonal B-LPD, the clonal proliferation of T cells, and EBV following ATG therapy. (A) Histochemical staining of an abdominal lymph node (100×). Inset right below for each panel was a high magnification image (400×). H&E, staining with hematoxylin and eosin; EBER, FISH of EBV-encoded RNA. (B-D) Southern blot analysis of DNA extracted from LPD lesions. Blots were hybridized with the IGH gene probe JH (B), EBV-specific DNA probe Bam HIW (C), and TCR gene probe Jγ (D). Arrows indicate rearranged bands. In panel B, DNA was digested with the restriction enzymes Bam HI (lane 1), both Bam HI and Hind III (lane 2), and Hind III (lane 3). In panel C, DNA was digested with Bam HI: lanes 1 and 2, positive and negative controls for EBV, respectively; lane 3, LPD lesion. Lane M, DNA molecular weight markers. In panel D, DNA was digested with Hind III: lane 1, lymphocytes of a healthy control; lane 2, LPD lesion. The arrow indicates a missing 5-kb fragment (TCR rearrangement). (E) Capillary electrophoresis of PCR products from the LPD lesion exhibiting T-cell clonality when assessed by TCRγ rearrangement. (F) Immunohistochemical detection of IL-10 and IL-6 in the kidney showing the marked infiltration of B-cells.

We attempted to identify the cells that permitted EBV-reactivation. The EBV of LPD lesions were clonal (Figure 2C). EBV potentially infects lymphocytes such as naïve B cells, T cells, and NK cells.4,5 LPD lesions were occupied mostly by EBV-negative B cells and by a small population of CD3+ lymphocytes (Figure 2A). These findings suggested that EBV originated from CD3+ T cells. The sparse T cells of LPD lesions (Figure 2A) showed clonal proliferation when analyzed by Southern blotting (Figure 2D) and the PCR-based gene clonality assay of TCR genes (Figure 2E),16 suggesting the clonal expansion of T cells infected with EBV. ATG for AA may not allow the predominant proliferation of clonal T cells and the immune surveillance of T cells, being partly supported by outbreak of serious infections (Figure 1B). Moreover, to determine the association between clonal T cells with oligoclonal B-LPD, we measured various cytokines17-19 that promote B-cell proliferation. Interferon g, IL-6, IL-10, and tumor necrosis factor were markedly increased in the serum (Table 1) and were also detected in LPD lesions (Figure 2F). T cells can produce these cytokines.18,19 Therefore, it is conceivable that ATG suppressed cytotoxic T cells and allowed the development of B-LPD. The predominant B-cell proliferation may be associated with B-cell selection by the cytokine and cytotoxicity responses. Based on our results, we consider that EBV-infected clonal T cells were critically involved in the development of EBV-negative oligoclonal B-LPD.

Conclusions

The molecular autopsy study revealed that the sparse EBV-infected clonal T cells could be critically involved in the pathogenesis of EBV-negative oligoclonal B-LPD through cytokine amplification and escape from T-cell surveillances attributable to ATG-based immunosuppressive therapy, leading to an extremely rare B-cell-rich T-cell lymphoma. This report may be helpful in elucidating the complex pathophysiology of intractable B-LPD refractory to rituximab, although further studies are needed to draw a conclusion.

Funding Statement

Funding: this work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, the Ministry of Labor and Welfare of Japan, the Takeda Science Foundation, and SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Dorr V, Doolittle G, Woodroof J. First report of a B cell lymphoproliferative disorder arising in a patient treated with immune suppressants for severe aplastic anemia. Am J Hematol 1996;52:108-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peres E, Savasan S, Klein J, et al. High fatality rate of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorder occurring after bone marrow transplantation with rabbit antithymocyte globulin conditioning regimens. J Clin Microbiol 2005;43:3540-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein MA, Achong BG, Barr YM. Virus Particles in cultured lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s lymphoma. Lancet 1964;1:702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speck P, Haan KM, Longnecker R. Epstein-Barr virus entry into cells. Virology 2000;277:1-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rickinson AB, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr Virus. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2007. pp 2397-2446. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna R, Burrows SR. Role of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in Epstein-Barr virus-associated diseases. Ann Rev Microbiol 2000;54:19-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landais E, Saulquin X, Houssaint E. The human T cell immune response to Epstein-Barr virus. Int J Dev Biol 2005;49:285-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Esser JW, van der Holt B, Meijer E, et al. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) reactivation is a frequent event after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) and quantitatively predicts EBV-lymphoproliferative disease following T-cell--depleted SCT. Blood 2001;98:972-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheinberg P, Fischer SH, Li L, et al. Distinct EBV and CMV reactivation patterns following antibody-based immunosuppressive regimens in patients with severe aplastic anemia. Blood 2007;109:3219-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oyama T, Ichimura K, Suzuki R, et al. Senile EBV+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathologic study of 22 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 2003;27:16-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milpied N, Vasseur B, Parquet N, et al. Humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (Rituximab) in post transplant B-lymphoproliferative disorder: a retrospective analysis on 32 patients, Ann Oncol 2000;11:S113-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruhn B, Meerbach A, Hafer R, et al. Preemptive therapy with rituximab for prevention of Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2003;31:1023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benkerrou M, Jais JP, Leblond V, et al. Anti-B-cell monoclonal antibody treatment of severe posttransplant B-lymphoproliferative disorder: prognostic factors and long-term outcome. Blood 1998;92:3137-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young NS. Bone marrow failure syndromes. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawaguchi T, Nakakuma H. New insights into molecular pathogenesis of bone marrow failure in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Int J Hematol 2007;86:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langerak AW, Groenen PJ, Bruggemann M, et al. EuroClonality/BIOMED-2 guidelines for interpretation and reporting of Ig/TCR clonality testing in suspected lymphoproliferations. Leukemia 2012;26:2159-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart JP, Rooney CM. The interleukin-10 homolog encoded by Epstein-Barr virus enhances the reactivation of virus-specific cytotoxic T cell and HLA-unrestricted killer cell responses, Virology 1992;191:773-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taga H, Taga K, Wang F, et al. Human and viral interleukin-10 in acute Epstein-Barr virus-induced infectious mononucleosis. J Infect Dis 1995;171:1347-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinrichs C, Wendland S, Zimmermann H, et al. IL-6 and IL-10 in post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders development and maintenance: a longitudinal study of cytokine plasma levels and T-cell subsets in 38 patients undergoing treatment. Transplant Int 2011;24:892-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]