Indoor tanning increases the risk of skin cancer, particularly among frequent users and those initiating use at a young age.1,2 While previous research has demonstrated that indoor tanning is common among youth,3 to our knowledge, this study provides the first national estimates of indoor tanning trends among this population.

Methods

We used data from the 2009, 2011, and 2013 national Youth Risk Behavior Surveys, which used independent, nationally representative samples of public and private US high school students in grades 9 through 12 (http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm). Indoor tanning was defined as using an indoor tanning device (eg, sunlamp, sunbed, tanning booth, excluding a spray-on tan) at least once during the 12 months before each survey period. Frequent indoor tanning was defined as using an indoor tanning device 10 or more times during the same period. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey had a student sample size of 16 410 in 2009, 15 425 in 2011, and 13 583 in 2013; overall response rates were 71%, 71%, and 68%, respectively. Data were weighted to account for oversampling of black and Hispanic students and nonresponse. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey protocol was approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Institutional Review Board. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey is conducted in accordance with parental permission procedures in each locality.

We stratified our analyses by sex because of differences between sexes in indoor tanning behavior.3 Temporal changes were examined using logistic regression that controlled for age and race/ethnicity. Linear time variables were treated as continuous and were coded using orthogonal coefficients. Data were analyzed using SUDAAN, version 10.1 (RTI International).

Results

Among female high school students during 2013, a total of 20.2% engaged in indoor tanning and 10.3% engaged in frequent indoor tanning. Among male high school students, 5.3% engaged in indoor tanning and 2.0% engaged in frequent indoor tanning. Indoor tanning was most common among non-Hispanic white female students (Table).

Table.

Prevalence of Indoor Tanning Among US High School Students, National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2013

| Characteristic | Female

|

Male

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.a | Indoor Tanning, % (95% CI)b | Frequent Indoor Tanning, % (95% CI)c | No.a | Indoor Tanning, % (95% CI)b | Frequent Indoor Tanning, % (95% CI)c | |

| All races/ethnicities, y | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| All ages | 6168 | 20.2 (16.1–25.1) | 10.3 (7.9–13.3) | 6411 | 5.3 (4.4–6.3) | 2.0 (1.7–2.7) |

|

| ||||||

| ≤14 | 676 | 10.7 (7.2–15.6) | 4.3 (2.6–7.0) | 614 | 3.6 (2.2–5.9) | 0.9 (0.4–2.1) |

|

| ||||||

| 15 | 1467 | 13.7 (9.4–19.6) | 6.3 (4.1–9.5) | 1412 | 3.5 (2.7–4.6) | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) |

|

| ||||||

| 16 | 1450 | 21.3 (16.3–27.2) | 10.0 (7.1–13.8) | 1506 | 4.2 (3.2–5.5) | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) |

|

| ||||||

| 17 | 1579 | 25.3 (20.6–30.6) | 13.6 (10.6–17.3) | 1653 | 5.1 (3.7–6.9) | 2.1 (1.3–3.4) |

|

| ||||||

| ≥18 | 970 | 28.5 (22.0–36.2) | 16.9 (11.6–24.0) | 1188 | 10.6 (8.2–13.6) | 3.9 (2.5–6.3) |

|

| ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white, y | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| All ages | 2532 | 30.7 (25.7–36.2) | 16.9 (13.8–20.5) | 2755 | 6.1 (5.0–7.5) | 2.2 (1.4–3.4) |

|

| ||||||

| ≤14 | 251 | 15.1 (9.6–23.1) | 7.0 (4.2–11.5) | 211 | 2.6 (0.9–7.6) | d |

|

| ||||||

| 15 | 640 | 20.6 (14.2–28.8) | 9.5 (6.2–14.2) | 601 | 3.9 (2.7–5.5) | 1.1 (0.5–2.3) |

|

| ||||||

| 16 | 608 | 32.4 (26.0–39.5) | 16.1 (12.0–21.2) | 655 | 4.5 (3.0–6.6) | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) |

|

| ||||||

| 17 | 649 | 38.7 (33.4–44.3) | 22.1 (18.4–26.3) | 758 | 6.0 (4.2–8.5) | 2.8 (1.5–5.1) |

|

| ||||||

| ≥18 | 384 | 41.6 (32.8–50.8) | 28.4 (20.9–37.4) | 530 | 13.2 (9.8–17.4) | 4.5 (2.4–8.1) |

|

| ||||||

| Non-Hispanic blackd | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| All ages | 1333 | 2.5 (1.6–3.9) | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 1310 | 3.2 (2.1–4.7) | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) |

|

| ||||||

| Non-Hispanic otherd | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| All ages | 693 | 9.7 (6.8–13.6) | 2.7 (1.6–4.6) | 635 | 4.7 (3.2–6.8) | 2.2 (1.3–3.6) |

|

| ||||||

| Hispanicd,e | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| All ages | 1513 | 7.9 (5.1–11.8) | 2.3 (1.3–4.0) | 1561 | 4.4 (2.8–6.8) | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) |

Number of respondents (unweighted). Unknown and missing responses were excluded from the analysis. Percentages are weighted to account for oversampling of black and Hispanic students and nonresponse.

Indoor tanning is defined as using an indoor tanning device (eg, sunlamp, sunbed, tanning booth) at least once during the 12 months before the survey and does not include getting a spray-on tan.

Frequent indoor tanning is defined as using an indoor tanning device (eg, sunlamp, sunbed, tanning booth) at least 10 times during the 12 months before the survey and does not include getting a spray-on tan.

Data cannot be presented by age group because of small cell sizes.

Persons identified as Hispanic might be of any race.

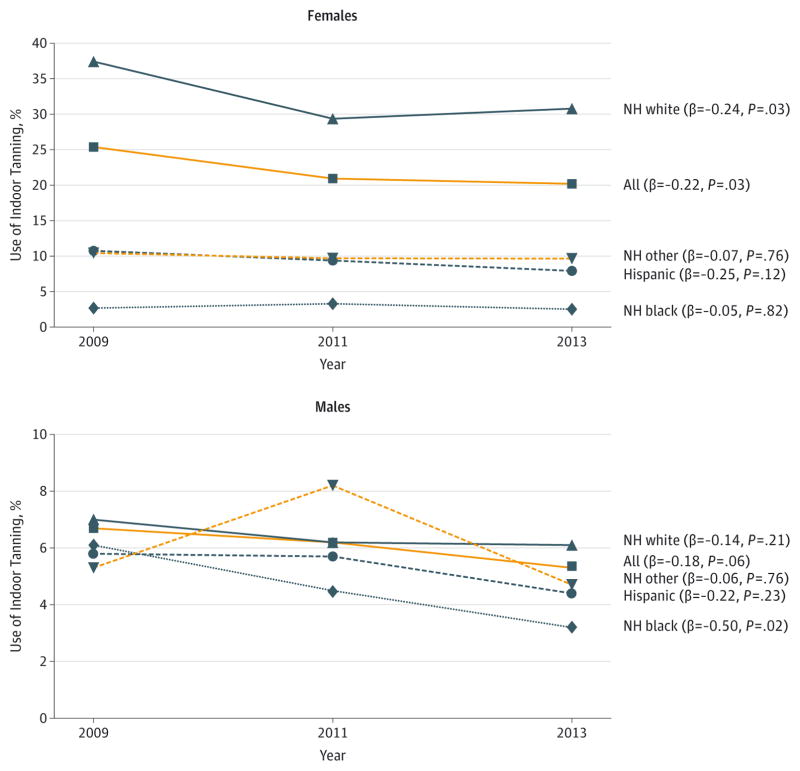

From 2009 to 2013, indoor tanning significantly decreased among female students (from 25.4% to 20.2%, β = −0.22, P = .03), non-Hispanic white female students (from 37.4% to 30.7%, β = −0.24, P = .03), and non-Hispanic black male students (from 6.1% to 3.2%,β = −0.50; P = .02)(Figure). Linear trends infrequent indoor tanning were not significant.

Figure. Trends in Indoor Tanning Among US High School Students, National Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2009–2013.

Indoor tanning is defined as using an indoor tanning device (eg, sunlamp, sunbed, tanning booth) at least once during the 12 months before the survey and does not include getting a spray-on tan. Changes in indoor tanning were examined using logistic regression analyses controlling for age (≤14, 15, 16, 17, and ≥18 years) and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic [NH] white, NH black, NH other, and Hispanic) among all races/ethnicities and ages in the race/ethnicity–specific analyses.

Discussion

These decreases in indoor tanning may be partly attributable to increased awareness of its harms. In 2009, the World Health Organization classified indoor tanning devices as carcinogenic to humans, and several studies have demonstrated that indoor tanning increases the risk of skin cancer.1,2,4 Furthermore, 40 states implemented new laws or strengthened existing laws between 2009 and 2013; of those, 11 states prohibited indoor tanning among those younger than 18 years.5 Evidence suggests that such laws are associated with lower rates of indoor tanning.6 In addition, a 10% excise tax on indoor tanning services was implemented in 2010, the effects of which are largely unknown.4

Despite these reductions, indoor tanning remains common among youth. The 2013 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey data suggest that an estimated 1.5 million female and 0.4 million male high school students engage in indoor tanning; most (1.6 million) are younger than 18 years. Early intervention is vital to prevent initiation and promote cessation of indoor tanning. The Surgeon General has highlighted the importance of reducing the harms from indoor tanning.4 Approaches include the US Food and Drug Administration reclassification of tanning devices from low to moderate risk and requiring a warning against the use of tanning devices by those younger than 18 years, limiting deceptive health and safety claims, and counseling fair-skinned individuals aged 10 to 24 years to avoid indoor tanning.4

Limitations of this study include its reliance on self-reported data, which are subject to bias. In addition, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey data are generalizable only to high school students and may not represent all persons in this age group. Despite these limitations, this study provides nationally representative estimates allowing for the evaluation of trends over time and progress toward protecting US youth from the harms of indoor tanning.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author Contributions: Dr Guy and Ms Berkowitz had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Guy, Berkowitz, Holman, Garnett, Watson.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Guy, Berkowitz, Everett Jones, Holman, Garnett.

Drafting of the manuscript: Guy, Berkowitz, Everett Jones, Garnett, Watson.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Guy, Berkowitz, Holman.

Statistical analysis: Guy, Berkowitz, Everett Jones.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Guy, Garnett, Watson.

Study supervision: Guy.

References

- 1.Colantonio S, Bracken MB, Beecker J. The association of indoor tanning and melanoma in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):847–857. e1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren MM, Han J, Qureshi AA, Linos E. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wehner MR, Chren MM, Nameth D, et al. International prevalence of indoor tanning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(4):390–400. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.6896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.AIM at Melanoma. [Accessed August 4, 2014];Ongoing legislation. http://www.aimatmelanoma.org/en/aim-for-a-cure/legislative-accomplishments-in-melanoma.html.

- 6.Guy GP, Jr, Berkowitz Z, Jones SE, et al. State indoor tanning laws and adolescent indoor tanning. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):e69–e74. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]