Abstract

The exocarp, or skin, of fleshy fruit is a specialized tissue that protects the fruit, attracts seed dispersing fruit eaters, and has large economical relevance for fruit quality. Development of the exocarp involves regulated activities of many genes. This research analyzed global gene expression in the exocarp of developing sweet cherry (Prunus avium L., ‘Regina’), a fruit crop species with little public genomic resources. A catalog of transcript models (contigs) representing expressed genes was constructed from de novo assembled short complementary DNA (cDNA) sequences generated from developing fruit between flowering and maturity at 14 time points. Expression levels in each sample were estimated for 34 695 contigs from numbers of reads mapping to each contig. Contigs were annotated functionally based on BLAST, gene ontology and InterProScan analyses. Coregulated genes were detected using partitional clustering of expression patterns. The results are discussed with emphasis on genes putatively involved in cuticle deposition, cell wall metabolism and sugar transport. The high temporal resolution of the expression patterns presented here reveals finely tuned developmental specialization of individual members of gene families. Moreover, the de novo assembled sweet cherry fruit transcriptome with 7760 full-length protein coding sequences and over 20 000 other, annotated cDNA sequences together with their developmental expression patterns is expected to accelerate molecular research on this important tree fruit crop.

Introduction

The exocarp, or skin, of fleshy fruit is a highly specialized tissue that forms the interface between the fruit flesh and the environment, and supports the mechanical integrity of the fruit. It is the outermost part of the fruit wall (pericarp), and typically comprises the epidermis and sub-epidermal cell layers.1 The exocarp protects the developing fruit against uncontrolled water loss or uptake, ultraviolet radiation, mechanical damage, pathogens and herbivores.2,3 Reflecting the diverse functions, cell walls in the exocarp are characterized through thickenings and other modifications, the most prominent one being the cuticle, or the cuticular membrane4 (CM). The cuticle is a complex layer of lipophilic materials such as cutin and waxes. It is localized in the outer periclinal and anticlinal cell walls of the epidermis, and in some fruit such as apple and tomato, may extend into the hypodermal cell walls. Furthermore, exocarp cells usually contain high levels of phenolic compounds, pigments, volatile esters and defense-related proteins.5 Several horticulturally relevant traits are also associated with the exocarp, such as color, resistance to pathogen infections and to fruit cracking. During ripening, the fruit becomes attractive to frugivores through changes in color, smell, flavor and texture. These changes also affect the exocarp. Further developmental changes affect the composition and load of the cuticle6–8 and the mechanical properties of the exocarp. For instance, the peel of tomato and grape berry stiffens towards maturity, which has been proposed to control fruit growth.9,10

The dynamic functions of the exocarp require a developmentally changing repertoire of biosynthetic activities and expressed genes. So far, global transcriptome studies of the whole fruit have uncovered a wealth of developmentally regulated genes in important fleshy fruit crops such as tomato,11 apple,12–14 grape berry,15,16 peach17,18 and date palm.19 Only a few studies on temporal changes of gene expression profiles in the developing exocarp have been published, and these have focused on tomato20–22 or grape berry.23 Other transcriptome analyses of the exocarp have concentrated on a single developmental stage (peach,24 grape berry,25 tomato,26 citrus27) or pooled developmental stages (pomegranate28).

Sweet cherry is an important fleshy, non-climacteric tree fruit crop grown in temperate regions worldwide. Like in other stone fruit such as the peach, the edible, fleshy part of the sweet cherry fruit consists of exocarp and mesocarp, while the endocarp develops to a hard shell enclosing the seed, together constituting the ‘stone’ or pit. So far, relatively little data on gene expression are available for sweet cherry fruit. This limits the ability to identify genes with important roles in developmental processes, which in turn limits breeding and production of superior fruit.

Recently, developmental and tissue-specific expression patterns were studied for 22 sweet cherry genes, 13 of which are potentially involved in cuticle formation and/or function in fruit.29 The present study is a comprehensive report of transcriptional changes that take place in the sweet cherry fruit exocarp over the developmental course from flowering to maturity. The objectives of this research were to (i) identify genes expressed in the sweet cherry exocarp; (ii) resolve temporal expression patterns of the exocarp-associated genes; and (iii) identify developmentally regulated processes characteristic to the exocarp on the basis of coregulated genes. Much of our past research has been on the development and function of fruit cuticles6,30,31 and fruit skin.32,33 In the present work, our particular interest was on genes involved in cuticle deposition. Other key processes we focused on included cell wall metabolism during fruit growth, maturation and softening; sugar transport; and transcriptional regulation. Together, the results reveal a complex chronology of simultaneous, consecutive and overlapping processes taking place in the developing sweet cherry exocarp.

Materials and methods

Sampling of fruit and determination of fresh mass, fruit surface area and fruit cuticle mass

Fruit from sweet cherry (Prunus avium L. ‘Regina’) trees grown in a commercial orchard in Gleidingen, Germany (09°84′E, 52°27′N), were used for all analyses. Flawless fruits, free of visible defects, were sampled, weighed and the fruit surface area calculated weekly as described previously.29 Cuticular membranes were isolated enzymatically; the mass of CM per unit surface area and per fruit and the CM thickness were determined as described previously.29

Total RNA extraction

Tissue samples for extraction of total RNA were collected weekly from full bloom to 94 days after full bloom (DAFB) (i.e., maturity) and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen within 10 min from removal of the fruit from the tree as described previously.29 Total RNA was isolated using the InviTrap Spin Plant RNA Mini Kit (Stratec Molecular GmbH, Berlin, Germany) with the lysis buffer RP.

Library preparation for RNA-Seq and sequencing

A total of 24 RNA samples isolated from following sweet cherry fruit tissues were used for transcriptome sequencing in one or two biological replicates as indicated in Figure 1c: whole ovaries (other floral organs removed) 3 DAFB; exocarp-enriched tissue (0.5–2 mm thin slices from the outermost pericarp) 10, 17, 24, 31, 38, 45, 52, 59, 66, 73, 80, 87 and 94 DAFB; mesocarp tissue 24 and 80 DAFB. The mesocarp samples served for detecting differential expression between exo- and mesocarp. Each biological replicate contained tissue from at least ten fruits collected from at least three trees.

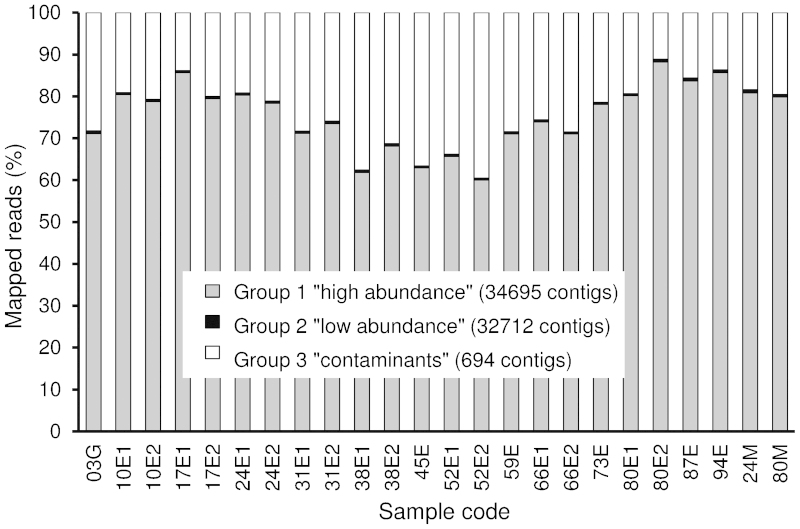

Figure 1.

Growth and development of the sweet cherry ‘Regina’ fruit analyzed in this study. (a) Fruit mass and surface area from flowering to maturity. Stage I, cell division and expansion; Stage II (gray shading), seed development and pit hardening; Stage III, cell expansion. Color change from green to red occurred between 59 and 66 DAFB (arrow). (b) Mass of CM per fruit and calculated rate of CM deposition. Data points in a and b show the average of 30 measurements; error bars represent s.e. (not visible if smaller than symbols). Time is given in DAFB. (c) Representative photos of the analyzed fruit and sample codes identifying the RNA-seq samples. The numbers in images indicate the developmental age of the fruit in DAFB. Sample codes contain information on fruit age in DAFB (3–94), tissue type (G, whole ovaries after removal of other floral organs; E, exocarp-enriched tissue; M, mesocarp only) and replicate number (1 or 2) if applicable. Photos not to scale.

Aliquots of total RNA were treated with DNase I (Fermentas, Schwerte, Germany), purified using MinElute RNA purification Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the integrity of the RNA was assessed using capillary electrophoresis (Bioanalyzer; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA); the RNA integrity numbers of the samples were 8.2–10. Directional complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries were prepared at the GenXPro GmbH (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). Briefly, total RNA samples were retreated with DNase (BaselineZero; Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI, USA); mRNA was captured using Dynabeads mRNA Purification Kit (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany) and decapped using tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (Epicentre Biotechnologies). RNA was fragmented using RNA fragmentation reagents (Ambion, Darmstadt, Germany). Fragment ends were repaired using T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB, Frankfurt am Main, Germany), and adapters RA3 and RA5 (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA; Supplementary Table S1) were ligated to 3′ and 5′ ends using truncated T4 RNA Ligase 2 (NEB) respective T4 RNA Ligase 1 (NEB). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen) and RTP primers (Illumina; Supplementary Table S1). The cDNA was amplified in 13–15 cycles of PCR using Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzymes, Schwerte, Germany) with RP1 and RPI1–24 primers with Index 1-24 (Illumina; Supplementary Table S1). Amplified cDNA libraries were separated via polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fragments of 200–250 bp were excised and eluted from the gel. Concentration of the cDNA was quantified using the RiboGreen assay kit (Invitrogen). Aliquots of four indexed cDNA samples each were pooled. The pools were spiked with 1% of PhiX174 DNA (Illumina) for sequencing quality control and the samples were sequenced using the Solexa/Illumina platform (HiSeq2000; Illumina Sequencing Kit TruSeq SBS v5) yielding 100 bp reads in the 5′ to 3′ direction of the mRNA. Base calling was done using the HiSeq Control Software packages v1.4.5, RTA v1.12.4, CASAVA v1.7.0 and OLB v1.9.0. Indexed reads were deconvoluted using a custom Perl script (GenXPro GmbH).

Pre-processing and de novo assembly of Illumina reads

The pre-processing and assembly pipelines are outlined below; details on hardware, operating systems, parameter settings and other specifics are given in Supplementary Method S1.

Deconvoluted reads were pre-processed locally. The quality of Illumina reads was assessed using the program FastQC 0.9.4 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Adapter sequences were removed from 5′ and 3′ ends using the program ea-utils.34 Poor quality bases at the 3′ end were removed using the tool FASTQ Quality Trimmer (FASTX-Toolkit; fastx-tools_0.0.13_binaries_Linux_2.6_amd64; http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/). Error correction of the remaining reads was done using Coral 1.335 and the standard Linux programs split and cat. To reduce data input for the de novo assembly, identical reads were merged using the FASTQ collapser of the FASTX-Toolkit and reads identical in sequence but different in length were merged using the program USEARCH 5.0.144.36

The pre-processed reads were assembled at the RRZN cluster system at the Leibniz Universität Hannover, Germany in a multistep process. Filtered reads were first assembled to contiguous sequences (contigs) using Velvet 1.1.0537 with k-mer sizes of 95–23 in increments of four and two different coverage cutoff setting (auto or 2); 38 assemblies in total. The contigs from Velvet assembly were cleaned of homopolymers, sequences of low complexity and adapter remnants using the program seqclean_x86_64 (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/software/). Twenty-two published (GenBank JU090712-JU090733), three unpublished sweet cherry contigs from the same assembly29 and the complete genome sequence of the phage phiX174 (GenBank J02482.1) were added to the Velvet contigs, which were then assembled via decremental clustering and assembly using the programs PAVE 3.038 and CAP339 in five rounds with decreasing stringency. Throughout the pre-processing, data were managed via the MySQL server.

Read mapping and BLAST searches

Transcript abundance was estimated by mapping the Illumina reads to the assembled contigs using the program Bowtie.40 To enable correct alignment of as many reads as possible the raw reads were trimmed to 65 bp by removing 5 bp from the 5′-end and 30 bp from the 3′-end of each read and one mismatch per mapped read was allowed. Reads that mapped to two or more contigs were randomly assigned to one contig. Contigs were first sorted in two groups based on contig length and number of mapped reads. Group 1, high abundance contigs of ≥200 bp length and total read count ≥30 per contig in each sample and ≥75 per contig in all 24 samples together; Group 2, low abundance contigs of <200 bp length or total read count per contig <30 reads/sample and <75 reads/all 24 samples. Homology analyses were performed using the BLAST program.41 To identify contigs likely originating from other sources than the sweet cherry mRNA, the high abundance contigs (Group 1) were aligned against Prunus persica chloroplast (NCBI RefSeq NC_014697.1), mitochondrial (NCBI RefSeq release 51, directory: mitochondrion), ribosomal RNA (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/rRNA/rRNA.tar), plant pathogen (ftp://ftp.plantbiology.msu.edu/pub/data/CPGR/all.plant_pathogen.wgs_and_complete_genome.fasta.gz), yeast (http://downloads.yeastgenome.org/sequence/S288C_reference/genome_releases/S288C_reference_genome_R64-1-1_20110203.tgz) and viral (NCBI RefSeq release 51, directory: viral) sequences. Contigs with highly significant BLASTN matches (e-value <10−100) in these searches were removed from Group 1 as a new Group 3. BLAST searches for Group 1 contigs were further performed in the PAVE platform. To identify highly similar sequences within the assembled contigs, each contig was used as query in a BLASTN search against all contigs with an e-value cutoff 10−100. BLASTX searches for significant hits with an e-value <10−15 were conducted against predicted peptides of peach (Peach v1.042), apple (Malus × domestica Genome v1.043), grape vine (Vitis vinifera 12X March 2010 release of the draft genome44), Arabidopsis (TAIR 10.045) and 25 previously assembled sweet cherry sequences29 (GenBank JU090712 to JU090733). Results of these BLAST analyses were also referred to as ‘PAVE hits’. The sequence data were downloaded from Phytozome v.8.046 except for the sweet cherry sequences. Contigs were estimated to contain a complete open reading frame based on the comparison with the predicted peptide sequence of its best PAVE hit. Group 1 contigs were additionally annotated based on the best hits (e-value <10−10) retrieved in a BLASTX search performed via the Blast2GO platform47 against the SwissProt database48 (as of August 2012). Contigs with no hits were further queried against the NCBI RefSeq and nr databases as of August 2012. Results of these BLAST analyses were also referred to as ‘B2G hits’.

InterProScan and gene ontology analyses

Contigs in group 1 were functionally annotated assigning InterPro matches49 and gene ontology (GO) terms via Blast2GO platform.47 InterPro scan was performed on the translated amino-acid sequences of the longest open reading frame (ORF) of each contig if ≥150 nucleotides in length. GO terms were extracted from the BLASTX matches (e-value <10−10, GO annotation threshold 55) against the Swiss-Prot database48 (as of August 2012). Contigs with no hits were further queried against the NCBI RefSeq and nr protein databases. Visualization and statistical analyses of the GO terms were performed using Blast2GO. Alternative GO annotation was conducted by extracting the GO terms assigned to the best P. persica and Arabidopsis hits (e-value <10−15) of each contig via the AgriGO platform.50

Determination of expression levels and clustering of co-expressed genes

Expression levels were estimated by calculating the numbers of expected fragments (reads) per kilobase of contig per million fragments mapped (FPKM).51 The data were visualized and analyzed using the Mayday workbench.52 Reproducibility of the FPKM values between two replicate samples was assessed from MA plots and by calculating the correlation between the FPKM values of all contigs in the two biological replicates. We made use of the replicate samples and removed from Group 1 all contigs that differed in their normalized FPKM values between any two replicates by 10% points or more. This filtered subset of 29 955 contigs was termed ‘Group 1F’ and used for most of the bio-informatic analyses. Clusters of co-expressed genes were identified using the neural gas and quality threshold clustering algorithms in Mayday workbench. Quality threshold cluster diameters were adapted to the data using the ‘search diameter for QT clustering’ option.

Estimating transcript levels using reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR

Reverse transcription-quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was carried out for selected genes as described earlier.29 Primer sequences are given in Supplementary Table S1.

GenBank accessions

The Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession GAJZ00000000 (contigs with predicted full-length ORFs were deposited) and the assembly name P.avium_v2.0. The version described in this paper is the first version, GAJZ01000000. The data are part of BioProject PRJNA73727.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the fruit, cDNA sequencing and de novo assembly of the sweet cherry transcriptome

Fruit growth exhibited three stages typical for stone fruit53 (Figure 1a). During Stage I—here, approximately from 0 to 30 DAFB—growth occurs by cell division and expansion in the entire pericarp. During Stage II (here, 31–45 DAFB) the endocarp (the innermost pericarp layer) and the seed develop, while the fruit mass and surface area remain essentially constant. Stage II was identified based on the second lag phase in the growth curve (Figure 1a) and on the beginning and completion of hardening of the endocarp (not shown). In Stage III (here, 52–94 DAFB) fruit mass and surface area increase rapidly, primarily due to the expansion of mesocarp cells. Here, maxima of surface area expansion rate occurred in Stage I at approximately 24 DAFB (39.0 mm2 day−1) and in Stage III at approximately 66 DAFB (60.0 mm2 day−1), as calculated from the data of surface area development in Figure 1a. As previously observed,6 cuticle mass per fruit increased rapidly during Stage I, the rate of CM deposition reaching a maximum of approximately 117 µg per fruit per day about 24 DAFB in the present study. Thereafter, the CM deposition rate steeply decreased in Stage II and further Stage III, averaging only 5.4 µg per fruit per day at 66 DAFB (Figure 1b), the time of the highest surface expansion rate.

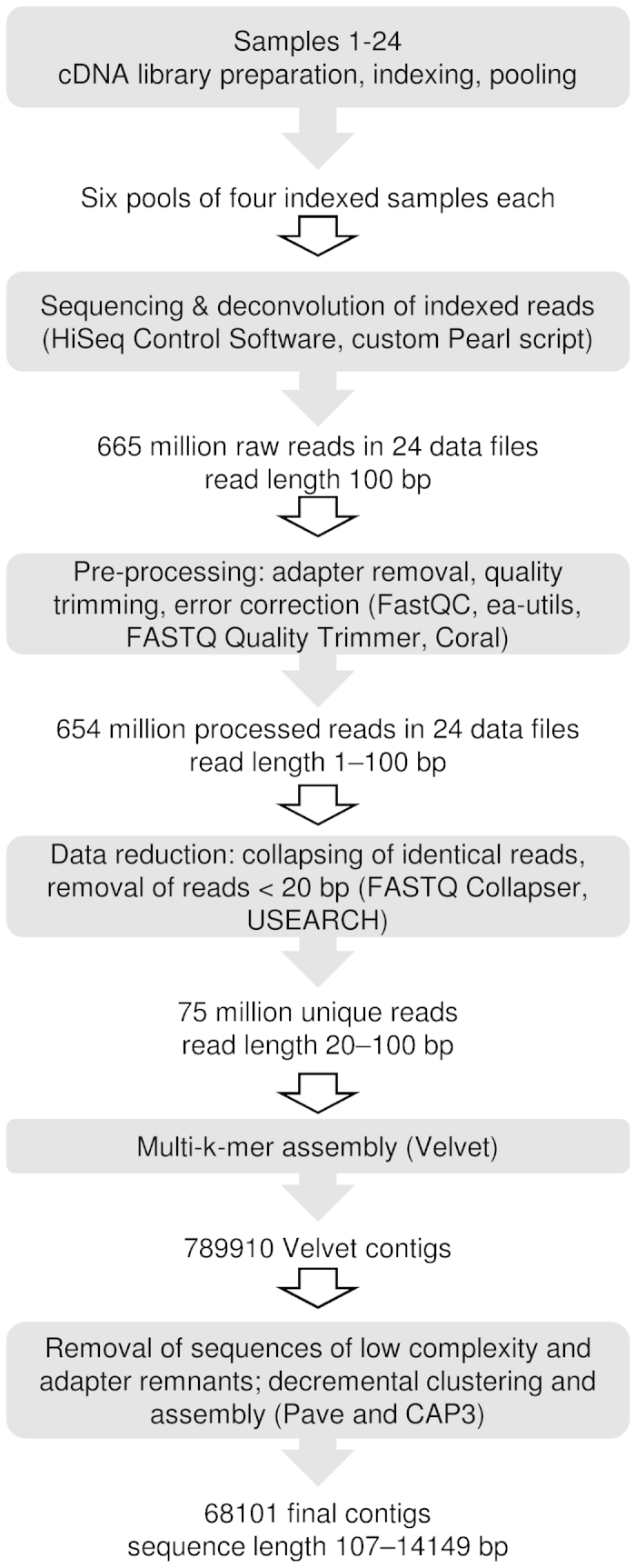

Tissue samples for RNA-seq analyses were collected in one or two biological replicates as indicated in Figure 1c. In total, cDNA generated from 24 individual samples representing 14 developmental time points was sequenced. The procedure and outcome of the sequencing, pre-processing, and assembly are outlined in Figure 2. Details on the pre-processing and assembly protocols, and the raw read and pre-processing results per sample are available as Supplementary Method S1, Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S1. Directional sequencing of 24 indexed samples in pools of four yielded a total of 665 million raw reads of 100 bp length each. After pre-processing and de novo assembly we obtained a final set of 68 101 assembled contigs of 107–14 149 bp length.

Figure 2.

Summary of the RNA-seq experiment, pre-processing of raw reads and de novo assembly of the sequence data. Details are given in section on ‘Material and methods’, Supplementary Method S1 and Supplementary Table S2.

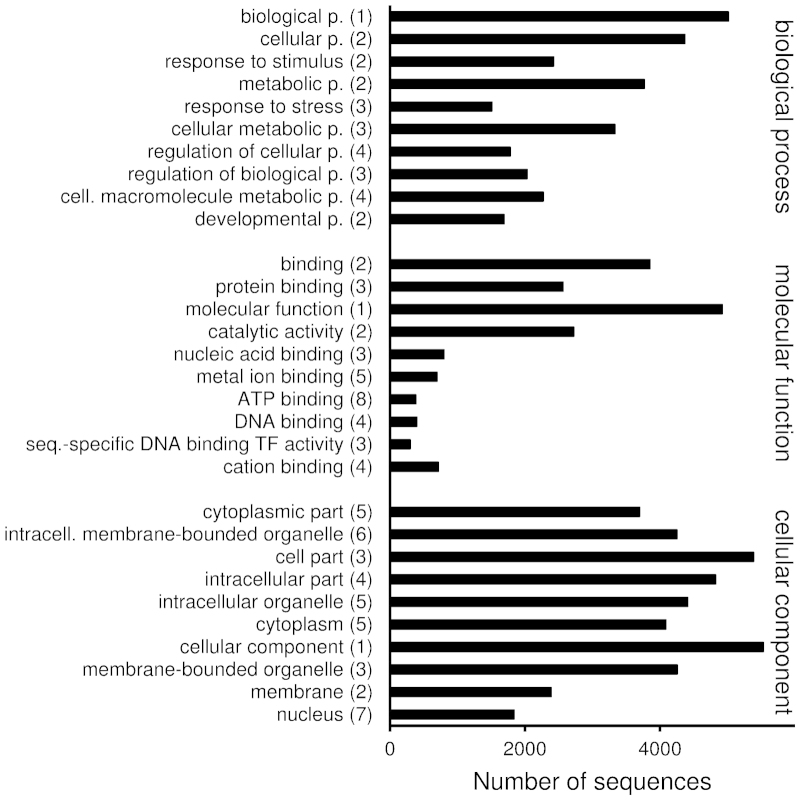

Mapping of trimmed reads to the de novo assembled contigs

To estimate the abundance of the mRNA represented by each contig in each sample, raw reads were trimmed to 65 nucleotides and remapped to the 68 101 contigs. Contigs were then separated into three groups based on the mapped read counts, results of BLASTn analyses and contig lengths. Group 1 (34 695 contigs or 51% of all contigs) consists of ‘high abundance’ contigs, or sequences represented by at least 30 reads per sample or 75 reads in all 24 samples; contigs shorter than 200 bp were excluded. Group 2 (32712 contigs or 48%) consists of ‘low-abundance’ contigs, or sequences with read counts below the set threshold of 30 reads per sample or 75 reads in all 24 samples. Group 3 (694 contigs or 1%) consists of probable contamination from viral, bacterial or other sources (data not shown). The assembled sequences in Groups 1 and 2 are available as Supplementary Data S1 and S2. The mapping results for all groups and samples are presented in Supplementary Table S3. For Group 1, the complete data on individual contigs including contig lengths, total read counts and BLAST results are available as Supplementary Table S4.

Table 1 summarizes statistics on contig length, GC content and other characteristics for Groups 1–3. Compared to other published plant transcriptomes that were assembled de novo from Illumina reads, the N50 value (1413 bp) and the average length (740 bp) of the Group 1 contigs are among the highest values reported.54 Considering that we used single reads instead of paired-end reads, this indicates that the chosen assembly strategy (pre-processing of the raw reads followed by multi-k-mer assembly using Velvet and super-assembly using CAP3) was successful. However, as with any de novo assembly, our assembly has its shortcomings. For instance, sometimes two or more contigs without a sequence overlap were most likely derived from a single transcript, as suggested by the alignment of the contigs to their shared best hit.

Table 1. Summary of all contigs. Contigs were assembled de novo from Illumina sequenced cDNA fragments generated from sweet cherry ‘Regina’ fruit sampled at different developmental stages. Group 1 and 3 were termed ‘high abundance’ and Group 2 ‘low abundance’ contigs, based on the number of mapped reads per contig; threshold 30 mapped reads per sample or 75 reads total in all 24 samples. Group 3 consists of contigs with BLASTn hits (e-value <1×−100) to bacterial, viral, rRNA or other sources as described in the section on ‘Materials and methods’.

| Total | Group 1 ‘high abundance’ | Group 2 ‘low abundance’ | Group 3 ‘contaminants’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of contigs | 68 101 | 34 695 | 32 712 | 694 |

| Number of bases in all contigs | 45 000 984 | 34 807 121 | 9 602 971 | 590 892 |

| Minimum contig length (bp) | 107 | 200 | 107 | 200 |

| Maximum contig length (bp) | 14 149 | 1 ,485 | 1482 | 14 149 |

| Median contig length (bp) | 370 | 740 | 261 | 436 |

| N50 contig length (bp)a | 1070 | 1413 | 291 | 1526 |

| Number of contigs ≥1 kb | 12 867 | 12 727 | 9 | 131 |

| Number of contigs ≥N50 | 11 874 | 7881 | 12 228 | 87 |

| GC content of the contigs (%) | 42.3 | 43.0 | 39.5 | 45.5 |

| Number of mapped readsb | 438 980 173 | 330 282 577 | 2 398 623 | 106 298 973 |

| Percentage of mapped reads | 66.0 | 49.6 | 0.4 | 16.0 |

50% of the bases in the contig set are in contigs longer/shorter than N50.

Raw reads were trimmed to 65 bp and mapped to contigs, one mismatch allowed.

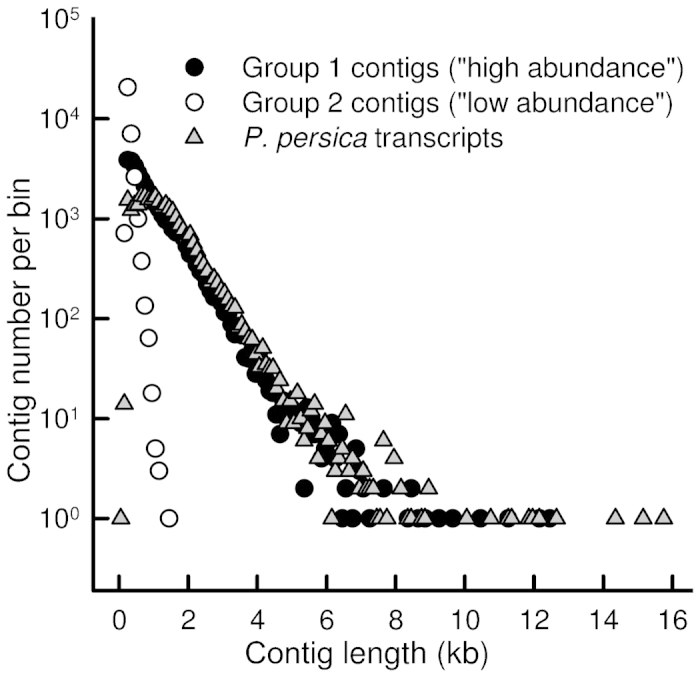

The length distribution of contigs in Group 1 was somewhat biased towards the contigs shorter than 600 bp, although a considerable number of the contigs were 2000 to 5000 bp long or longer (Figure 3 and Table 1). This length distribution is similar to that of the P. persica predicted transcripts (Figure 3). A total of 330 million reads (49.6% of all reads) mapped to Group 1 contigs, 99.8% of them being unique matches; 16.0% mapped to Group 3 and only 0.4% to Group 2 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S3). Averaging over the 24 samples, 75% (s.d. 8%) of the mappable reads mapped to Group 1 contigs, 24% (s.d. 8%) to Group 3 and 0.5% (s.d. 0.1%) to Group 2 (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Length distribution of assembled sweet cherry ‘Regina’ contigs in Group 1 (‘high abundance’, 34695 contigs, length 200–12 485 bp) and Group 2 (‘low abundance’, 32 712 contigs, 107–1482 bp). Length distribution of predicted transcripts in the P. persica genome (v.1.0) (28 702 sequences, 96–15 738 bp) is shown for reference. The x-values give the center of each bin; bin width is 100 bp, except for the first bin which is from 1 to 98 bp. Note logarithmic scale of the y-axis; bins with 0 sequences not shown.

Figure 4.

Distribution of the mapped reads between the contigs in Groups 1, 2 and 3 in each of the 24 RNA samples from sweet cherry ‘Regina’ fruit. For sample codes, see Figure 1.

Gene expression levels were estimated by calculating FPKM values (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads51), which normalize the raw read counts against the length of the contig and the total number of mappable reads in each sample. Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the FPKM values for all Group 1 contigs in two replicate samples, available for eight developmental stages, ranged from 0.900 (38 DAFB) to 0.996 (66 DAFB), meeting the proposed standard for RNA-seq experiments.55 MA plots, created in the Mayday workbench using the FPKM values analogous to the method proposed by Wang et al.,56 indicated only minor differences between replicates (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Annotation of the assembled contigs: BLAST searches, gene ontology analyses and InterProScan

To detect similarities between the sweet cherry contigs and proteins in other plants, two independent BLAST searches were performed. First, the contigs were aligned against sweet cherry, peach, apple, grape vine and Arabidopsis predicted peptides via the platform PAVE.38 The second round of BLAST searches were performed against the SwissProt, RefSeq and nr databases via the platform Blast2GO (B2G).47 The results of these BLAST searches against the two sets of databases are referred to as ‘PAVE hits’ and ‘B2G hits’, respectively. Results are shown for contigs that were detected at similar abundance levels in both biological replicates, where applicable. This subset of contigs covered 86% of all Group 1 contigs and was termed Group 1F (see also the section on ‘Materials and methods’). In Group 1F, 23 603 contigs (79%) had PAVE hits, while 74% of the contigs had B2G hits (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4). Notably, several contigs without significant hits to P. persica predicted peptides and complete ORFs sometimes had highly significant hits against the P. persica genomic sequence. Although potentially functional,57 such non-coding transcripts were not analyzed further.

Table 2. Annotation summary of all Group 1F contigs and of the Group 1F contigs containing a full-length ORF. Group 1F consists of Group 1 contigs differing less than 10% points in the relative expression levels between two biological replicates. Similarity searches were performed via the platform PAVE against P. persica, M. domestica, V. vinifera, A. thaliana and P. avium peptides and via Blast2GO (B2G) against Swiss-Prot, NCBI RefSeq and nr databases as described in the section on ‘Materials and methods’.

| All contigs |

Contigs with complete ORF |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| Total | 29 955 | 100 | 7628 | 100 |

| Has BLASTx hit(s) (PAVE)a | 23 603 | 79 | 7628 | 100 |

| Best hit to P. persica | 21 381 | 71 | 7350 | 96 |

| Best hit to M. domestica | 1845 | 6.2 | 221 | 2.9 |

| Best hit to V. vinifera | 263 | 0.9 | 21 | 0.3 |

| Best hit to A. thaliana | 70 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.03 |

| Best hit to P. avium | 44 | 0.1 | 34 | 0.4 |

| Has BLASTx hit(s) (B2G)b | 22 259 | 74 | 7581 | 99 |

| First hit to Swiss-Prot | 15 696 | 52 | 5849 | 77 |

| First hit to RefSeq | 5557 | 19 | 1554 | 20 |

| First hit to nr | 1006 | 3.3 | 178 | 2.3 |

| Has GO annotation (B2G) | 17 610 | 59 | 6,268 | 82 |

| GO biological process | 13 724 | 46 | 4,992 | 65 |

| GO cellular component | 14 492 | 48 | 5,528 | 72 |

| GO molecular function | 14 041 | 51 | 4,930 | 65 |

| InterProScan match | 21 459 | 72 | 7,407 | 97 |

e-value ≤1×10−15.

e-value ≤1×10−10.

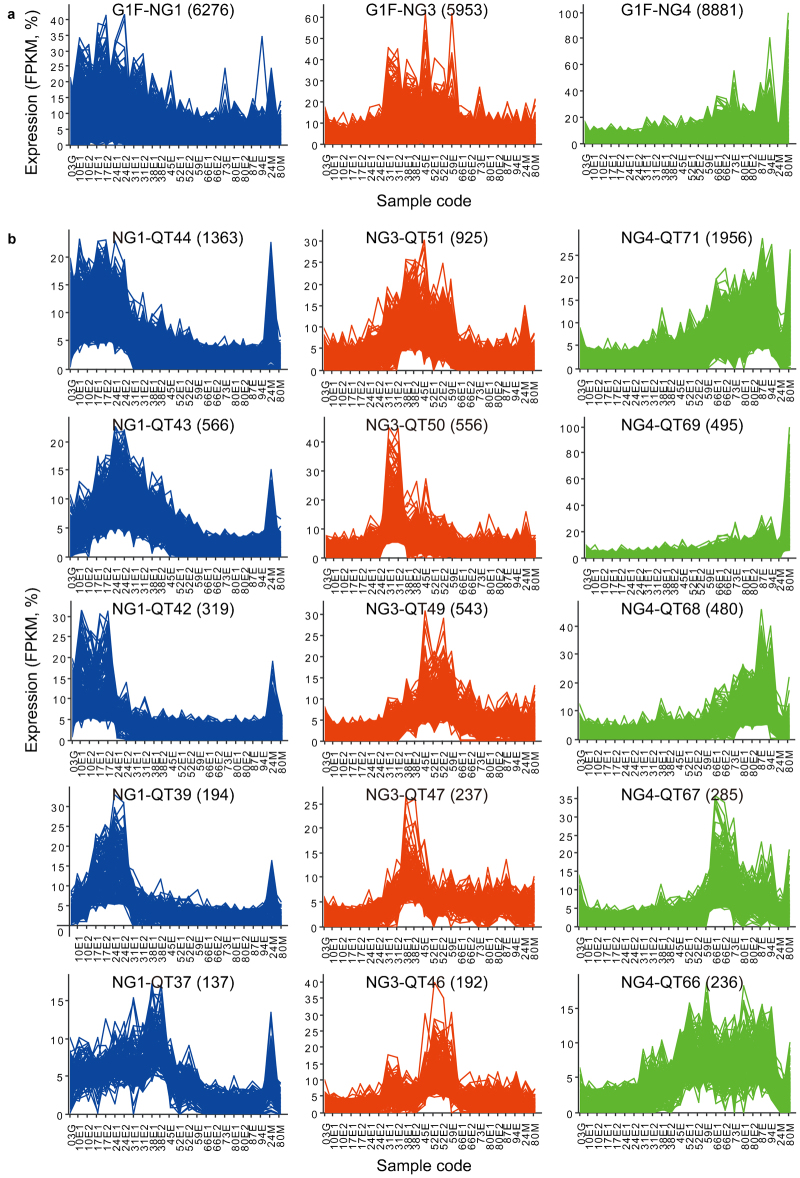

To estimate how well the assembled contigs represent expression of real genes and not just random sequences, a brief summary is given on the Group 1F contigs containing full-length ORFs. A full-length ORF was identified in 7628 contigs (25% of all), when the presence of a full-length ORF was predicted based on the alignment of the contig to its most similar PAVE hit: complete coverage from start to stop codon indicated a full-length ORF. More contigs are likely to be predicted to include full-length ORFs, if a different ORF finding procedure is applied. Here, the contigs with predicted full-length ORFs in Group 1F were 247–12 130 bp long (median 1563 bp; Supplementary Table S4). Ninety-six percent of them had best hits against P. persica, 77% had SwissProt hits, 97% had InterProScan matches and 82% had GO terms assigned (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S4). The InterProScan matches and GO terms assigned were largely consistent with each other and with the functions suggested by the best hits (Supplementary Table S4).The assigned GO terms covered a wide range of processes, functions and cellular compartments from ‘cell division’ (171 contigs) and ‘chloroplast’ (1042 contigs) to ‘transcription factor activity’ (300 contigs) and ‘response to stimulus’ (2424 contigs) (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 5.

GO terms of 7628 Group 1F contigs with predicted full-length open reading frames. GO terms in categories biological process, molecular function and cellular component were retrieved from combined graph analyses performed in Blast2GO platform (sequence filter 100, score alpha 0.6, node score filter 100). The GO terms are sorted in descending graph score order; numbers in parentheses indicate annotation levels.

Based on sequence comparison with 1521 predicted transcription factors of P. persica genome,58 1009 contigs representing transcription factors in Group 1F were identified, 410 of which contained a full-length ORF (Supplementary Table S4). Of the 58 transcription factor families in P. persica, 54 were represented in Group 1F, and full-length ORFs were identified from 50 families. Among the contigs with full-length ORF, the largest transcription factor family was bZIP (33 contigs, or 8.0% of the 410 predicted transcription factors). Assuming that the distribution of TFs in sweet cherry genome is similar to the one in peach genome, the bZIP family is over-represented in fruit (51 genes or 3.4% of all TFs in peach). In peach genome, the largest transcription factor family is bHLH (130 members or 8.5% of all transcription factors); in the sweet cherry fruit transcriptome, bHLH family ranks fourth (26 contigs or 6.3%). Other TF families with at least 20 contigs with predicted full-length ORFs in Group 1F were MYB (30), C2H2 (26), WRKY (24), ERF (22) and C3H (20).

Exocarp-specific transcripts are related to epidermis development and stress responses

To systematically identify exocarp-specific transcripts, contigs with normalized FPKM values in the mesocarp samples below 1% were considered as ‘exocarp-specific’. Normalized FPKM values per sample were calculated after setting the sum of FPKM values in all 24 samples to 100%. According to this criterion, 1162 contigs in Group 1F were exocarp-specific, 219 of which contained a full-length ORF (Supplementary Table S4). Gene ontology term enrichment analyses assigned several known epidermis-related processes and functions to the exocarp-specific contigs. For instance, in the category ‘biological process’, the most over-represented GO terms (false discovery rate <0.05) were ‘wax biosynthetic process, ‘cutin biosynthetic process’ and ‘response to salicylic acid stimulus’ (Table 3). Wax and cutin biosyntheses are essential for cuticle formation, whereas salicylic acid signaling plays a major role in pathogen defense. The specific, over-represented biological processes assigned to the exocarp-specific contigs may be summarized as follows: (i) epidermis development; (ii) responses to biotic and abiotic stresses; (iii) hormone responses; and (iv) secondary metabolism (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S6). In the category ‘molecular function’, the most specific GO terms assigned to the contigs with full-length ORF were ‘carboxylesterase’, ‘transcription factor’, ‘monooxygenase’, ‘fatty acid elongase’ and ‘polyol transmembrane transporter’ activities (Table 3 and Supplementary Table S6). In the category ‘cellular component’, the only over-represented GO term was ‘apoplast’. Collectively, the GO term enrichment analyses confirmed that our ‘exocarp-specific’ contigs with full-length ORFs realistically reflect genes with preferential or specific expression in the fruit skin. The GO term enrichment analysis was repeated on all 1162 exocarp-specific contigs identified in Group 1F (Supplementary Table S6). The results were in line with the results for the contigs with predicted full-length ORFs. Expectedly though, the number of over-represented GO terms were larger for the 1162 contigs (253) than for the 219 contigs (91) (Supplementary Table S6). The most specific over-represented GO terms not identified among the 219 full-length ORF contigs included ‘protein autophosphorylation’, ‘glucosinolate’,’ cyanide’ and ‘terpenoid biosynthetic’ processes.

Table 3. Over-represented GO terms in 219 Group 1F contigs with predicted full-length open reading frame and preferential expression in the exocarp (FPKM values in the mesocarp <1% of total FPKM values in all 24 samples). GO term enrichment was determined in a Fisher’s exact test and the result reduced to most specific terms; 20 most over-represented terms are shown. Complete results including contig identifiers available as Supplementary Table S6.

| GO term (category) | Nr. | FDR |

|---|---|---|

| Wax biosynthetic process (P) | 10 | 6.04×10−8 |

| Cutin biosynthetic process (P) | 7 | 4.03×10−7 |

| Response to salicylic acid stimulus (P) | 20 | 4.03×10−7 |

| Carboxylesterase activity (F) | 10 | 1.07×10−6 |

| Response to jasmonic acid stimulus (P) | 19 | 1.07×10−6 |

| Trichome morphogenesis (P) | 10 | 8.12×10−5 |

| Cinnamic acid biosynthetic process (P) | 6 | 8.12×10−5 |

| Response to wounding (P) | 17 | 5.42×10−4 |

| Response to UV-B (P) | 9 | 7.92×10−4 |

| Sequence-specific DNA binding TF activity (F) | 21 | 1.10×10−3 |

| Mucilage bios. p. involved in seed coat development (P) | 5 | 1.45×10−3 |

| Response to ethylene stimulus (P) | 13 | 2.35×10−3 |

| Flavonoid biosynthetic process (P) | 10 | 2.76×10−3 |

| Long-chain fatty acid transport (P) | 4 | 3.15×10−3 |

| Response to auxin stimulus (P) | 15 | 3.36×10−3 |

| Monooxygenase activity (F) | 10 | 4.27×10−3 |

| Apoplast (C) | 13 | 4.68×10−3 |

| Response to abscisic acid stimulus (P) | 21 | 8.27×10−3 |

| Defense response to fungus (P) | 12 | 9.46×10−3 |

| Very long-chain fatty acid metabolic process (P) | 5 | 9.46×10−3 |

Abbreviations: C, cellular component; F, molecular function; FDR, false discovery rate; FPKM, fragments (reads) per kilobase of contig per million fragments mapped; Nr, number of contigs annotated with the given GO term; P, biological process; TF, transcription factor; UV, ultraviolet.

Forty most abundant sweet cherry contigs and their expression patterns

Next, we examined the forty most highly represented contigs in the sweet cherry skin transcriptome (Table 4; details on the sequences in Supplementary Table S4). The most abundant contig by far was Pa_24402 with a FPKM sum of 523 781 over the 24 samples, or 4.2 million mapped reads total. Its best B2G hit was GenBank accession P50694, a glucan endo-1,3-β-glucosidase or thaumatin-like protein, the most abundant soluble protein in the ripe sweet cherry fruit.59 Five other ‘Top 40’ contigs also had B2G hits to published P. avium sequences: Pa_11846 (P. avium allergen 1), Pa_29501 (non-specific lipid transfer protein), Pa_00414 (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase 1), Pa_21625 (thaumatin-like protein) and Pa_03818 (anthocyanidin 3-O-glucosyltransferase). Altogether, based on the best hit descriptions, 11 of the 40 most abundant contigs represent proteins likely related to abiotic and biotic stresses, such as oxidative stress and responses to pathogens. Also, three further contigs described as putative transport proteins may also be associated with defense responses such as metallothionein-like proteins60 and lipid transport protein.61 The latter are predominantly expressed in surface tissues,61 including citrus and tomato fruit.26,27 While relevant in constitutive and acute stress responses, many stress defense proteins were proposed to have other, developmental functions as well. For instance, Pa_10497 is a tentative S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase proenzyme, the key enzyme in the biosynthesis of polyamines, essential for stress responses and growth.62 The other Top 40 transcripts encode cell wall structural proteins and expansins (eight contigs), proteins involved in protein biosynthesis or turnover (three contigs), enzymes of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway (two contigs) and proteins related to cytoskeleton, gluconeogenesis, photosynthesis or unknown functions (one contig each) (Table 4). Nine transcripts produced no hits in the BLASTx searches against SwissProt, RefSeq or nr databases with the applied settings. In addition to the above mentioned lipid transfer proteins, many of these Top 40 contigs from sweet cherry fruit were homologous to abundant transcripts in other fruits. For instance, abundant metallothionein expression was also reported in other fruits including banana63 and pineapple.64 Furthermore, several best hit descriptions were similar to the annotations of the most abundant transcripts in the peel transcriptome of pomegranate.28 Common best hit descriptions included metallothionein, tubulin, lipid transfer protein, catalase, cysteine protease and S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase.

Table 4. Forty most abundant mRNA sequences (contigs) in the transcriptome of developing sweet cherry ‘Regina’ fruit. Additional information about these sequences is given in Supplementary Table S4.

| Contig ID | Length (bp) | FPKM total | B2G best hit e-value | B2G best hit definition | Tentative function or process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pa_24402 | 537 | 523 781 | 1.3×10−135 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase; TLP; allergen Pru av 2 | Stress |

| Pa_20288 | 606 | 269 571 | 6.9×10−35 | Extensin-3 | Cell wall |

| Pa_49067 | 411 | 250 297 | 2.9×10−49 | Extensin-3 | Cell wall |

| Pa_47876b | 472 | 169 152 | 1.8×10−31 | Proline-rich extensin-like protein EPR1 | Cell wall |

| Pa_11846a | 690 | 160 873 | 3.6×10−112 | Major allergen Pru av 1 | Stress |

| Pa_25400 | 432 | 152 331 | No hit | Unknown | |

| Pa_47716 | 483 | 140 243 | 5.4×10−28 | Dehydrin COR47; cold-induced COR47 protein | Stress |

| Pa_29501a,b | 581 | 112 730 | 5.3×10−79 | Nonspecific lipid-transfer protein; allergen Pru av 3 | Transport |

| Pa_53685 | 298 | 109 269 | No hit | Unknown | |

| Pa_50270 | 369 | 104 741 | No hit | Unknown | |

| Pa_10726 | 820 | 99 920 | 8.1×10−42 | Protein E6 | Unknown |

| Pa_39995 | 357 | 94 862 | 1.8×10−27 | Phosphoprotein ECPP44 | Stress |

| Pa_49183 | 405 | 85 504 | no hit | Unknown | |

| Pa_13183 | 905 | 76 502 | 0 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | Gluconeogenesis |

| Pa_46196 | 679 | 75 477 | 4.2×10−107 | Probable xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase | Cell wall |

| Pa_21625 | 829 | 69 722 | 2.4×10−138 | Glucan endo-1,3-beta-glucosidase; TLP; allergen Pru av 2 | Stress |

| Pa_28260a | 537 | 65 818 | 1.2×10−21 | Conserved hypothetical protein | Unknown |

| Pa_11084 | 806 | 62 814 | 3.0×10−13 | Metallothionein-like protein type 3 | Transport |

| Pa_35173a | 469 | 62 774 | 4.0×10−14 | Arabinogalactan peptide 15 | Cell wall |

| Pa_21347a,b | 750 | 58 838 | 1.2×10−100 | Major allergen Pru ar 1 | Stress |

| Pa_21722 | 398 | 57 020 | 3.0×10−12 | Polygalacturonase inhibitor 1; PGIP-1 | Stress |

| Pa_06786 | 1089 | 55 517 | 0 | Leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase | Flavonoid bs. |

| Pa_11167b | 1090 | 54 012 | 4.5×10−59 | Extensin-1 | Cell wall |

| Pa_30361 | 338 | 53 527 | 1.6×10−47 | Chalcone synthase 2; Naringenin-chalcone synthase 2 | Flavonoid bs. |

| Pa_59559 | 240 | 48 770 | No hit | Unknown | |

| Pa_13457a | 894 | 48 742 | 2.1×10−18 | Major latex allergen Hev b 5 | Stress |

| Pa_44191 | 283 | 47 095 | No hit | Unknown | |

| Pa_54252 | 291 | 46 745 | No hit | Unknown | |

| Pa_16626 | 537 | 46 455 | 1.0×10−61 | Ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain | Photosynth. |

| Pa_11118 | 1257 | 44 566 | 1.4×10−151 | Catalase isozyme 1 | ROS detoxification |

| Pa_23720a | 638 | 41 644 | 7.9×10−17 | Universal stress protein A-like protein | Stress |

| Pa_05806 | 1627 | 41 123 | 0 | Polyubiquitin | Protein turn-over |

| Pa_18352 | 1480 | 37 174 | 2.7×10−104 | Cysteine proteinase RD21a | Protein turn-over |

| Pa_32379b | 348 | 36 122 | 6.6×10−55 | Glycine-rich cell wall structural protein; precursor | Cell wall |

| Pa_01373 | 771 | 35 506 | 4.0×10−62 | Probable xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase | Cell wall |

| Pa_21518a | 645 | 35 305 | 3.6×10−40 | Metallothionein-like protein type 2 | Transport |

| Pa_21558 | 303 | 35 275 | 1.8×10−29 | Tubulin alpha chain | Cytoskeleton |

| Pa_10497a | 1760 | 35 073 | 4.0×10−175 | S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase proenzyme | Stress |

| Pa_29840 | 342 | 34 516 | 1.3×10−43 | Elongation factor 1-alpha | Translation |

| Pa_44188 | 348 | 33 983 | No hit | Unknown |

Abbreviations: bs., biosynthesis; FPKM, fragments (reads) per kilobase of contig per million fragments mapped; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Contig was predicted to contain a full-length open reading frame.

Expression preferentially in exocarp (FPKM values in mesocarp 24 and 80 DAFB below 1% of the total sum of FPKM values in all samples).

Functions of the Top 40 contigs in sweet cherry transcriptome were further predicted by means of GO analyses. Of the 136 GO terms assigned to the Top 40 contigs, three cell wall-related terms were over-represented as compared to all Group 1F contigs (Supplementary Table S7). Other relevant GO terms in the category ‘cellular component’ were associated with vacuole, plasma membrane or plastid. In the category ‘biological process’, the most relevant GO terms included ‘response to stimulus’ and ‘developmental processes’, while in the category ‘molecular function’, the most relevant GO terms were ‘binding’ and ‘hydrolase activity’ (Supplementary Table S7).

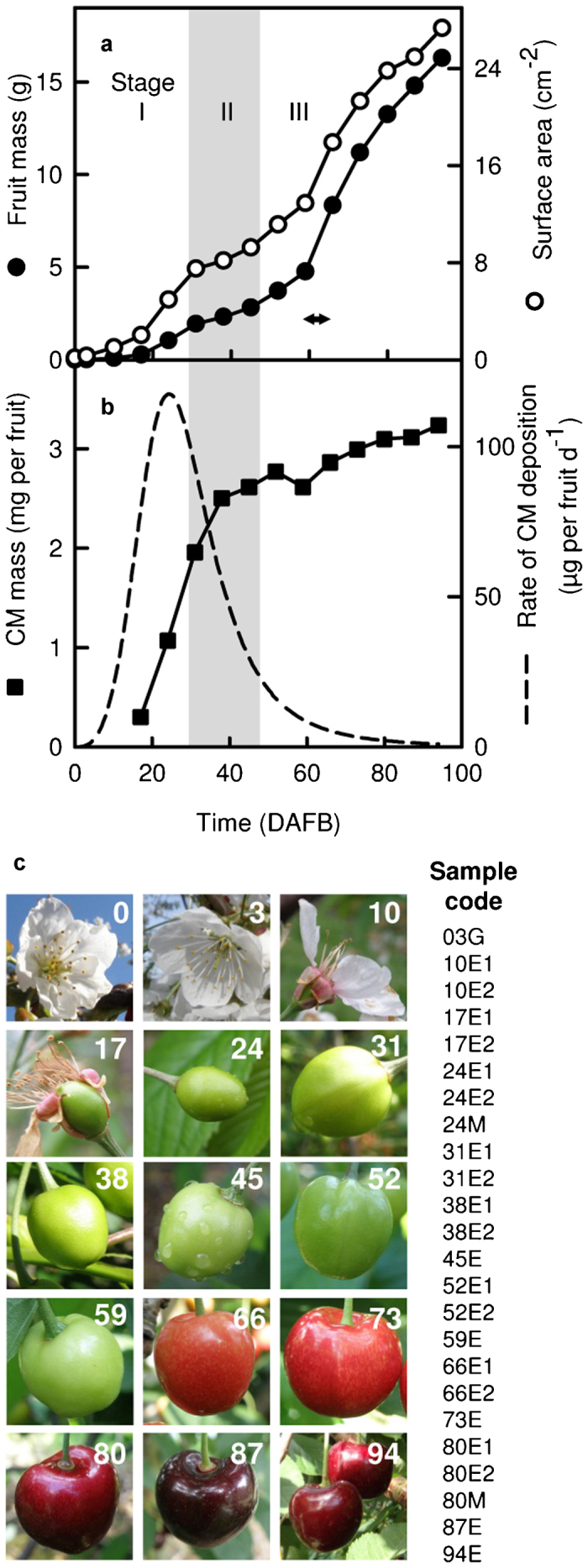

Global expression patterns in developing sweet cherry fruit: detection of five main patterns of gene expression

We identified expression patterns or clusters on the whole transcriptome scale and focused on the exocarp-specific genes within selected clusters. Two partitional clustering algorithms implemented in the Mayday workbench52 were used: The neural gas (NG) algorithm was applied to separate Group 1F contigs in five large clusters, followed by quality threshold (QT) clustering for more detailed expression patterns (see the section on ‘Materials and methods’). Neural gas clusters NG1 to NG5 contained 3053 to 8881 contigs each (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Each NG cluster had a characteristic average or centroid expression pattern: elevated expression during Stages I and II (NG1), in the ovary shortly after flowering (0–10 DAFB; NG2), during Stage II and early Stage III (NG3), from mid-Stage II to maturity (NG4) and mainly in the mesocarp (NG5) (Supplementary Fig. S3a and Fig. 6a). Several over-represented GO terms were detected in each NG cluster (Supplementary Table S8). For instance, in cluster NG2, the most specific, over-represented GO terms were related to translation, transcription and cell division. These functions are consistent with the high RNA levels in the tissue collected 3 and 10 DAFB (data not shown), reflecting the high cell division activity characteristic for this early stage of fruit development. Based on the GO analysis and the expression patterns, we expected to find the most exocarp-relevant contigs in clusters NG1, NG3 and NG4. Therefore, the following analyses concentrated on these three NG clusters. Only the GO terms in the category biological process will be considered below; the complete results are available in Supplementary Table S8.

Figure 6.

Selected expression patterns within the sweet cherry ‘Regina’ fruit skin transcriptome. (a) All 29 955 contigs in Group 1F (G1F) were first clustered in five clusters applying the NG algorithm on the normalized expression patterns. Clusters NG1, NG3 and NG4 are shown. (b) Each NG cluster was reclustered applying the QT clustering algorithm (cluster diameters adapted to data, minimum cluster size 20 contigs). Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of contigs in each cluster. Selected clusters are shown. Sample codes as in Figure 1. The complete set of cluster plots available as Supplementary Fig. S3.

Cluster NG1 contained 285 exocarp-specific contigs. Here, the most specific, over-represented terms were wax biosynthetic process, cutin biosynthetic process and fatty acid elongation. Other significantly over-represented, specific GO terms were (also) related to cuticle development, lipid metabolism, suberin biosynthetic process, responses to abiotic and biotic stimuli, cell-to-cell signaling and trichome differentiation. Suberin is typically present in endodermis and periderm, but not in the young fruit. Possibly, contigs annotated as related to suberin biosynthesis in fact participate in cutin biosynthesis, as suberin and cutin contain similar aliphatic monomers such as ω-hydroxy acids.65 Cluster NG3 contained 493 exocarp-specific contigs. The most specific, over-represented GO terms here were response to salicylic acid stimulus, anthocyanin accumulation in tissues in response to ultraviolet light and response to abscisic acid stimulus (Supplementary Table S8). Other over-represented GO terms included responses to biotic and abiotic factors, cell wall thickening and transmembrane transport, as well as terpenoid, polysaccharide and phenylpropane metabolism. In cluster NG4, the most specific, over-represented GO terms assigned to the 307 exocarp-specific contigs were response to salicylic acid stimulus, response to ethylene stimulus and response to bacterium. Other GO terms were related to protein autophosphorylation, response to biotic and abiotic factors, secondary metabolism and polyol transport.

To summarize these GO term enrichment results for the three NG clusters, the most typical, exocarp-specific processes during Stages I, II, and III of the sweet cherry fruit development were cuticle formation and deposition, response to abscisic acid (ABA) and response to ethylene stimuli, respectively. Throughout the development, the exocarp is specifically engaged in defense responses to various biotic and abiotic factors. The expression data support the view that constitutive expression of defense genes in the sweet cherry exocarp protects the developing fruit and contributes to developmentally regulated resistance to pathogens.66,67 The results are also consistent with the view that the defense-related proteins may have other developmental roles as well.68

Global expression patterns in developing sweet cherry fruit: identification of distinct patterns of coregulated genes

For fine resolution of expression patterns, the clusters NG1, NG3 and NG4 were subjected to QT clustering (minimum cluster size 20 contigs), resulting in 44, 51 and 71 QT clusters, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Selected QT clusters are shown in Figure 6b. Selected contigs are listed in Table 5 and their expression patterns are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3b. To estimate the reliability of the expression patterns obtained using RNA-seq, we additionally determined expression levels for selected contigs in Table 5 using RT-qPCR (Supplementary Fig. S4). For the seven contigs, representing transcripts putatively relevant for cuticle formation, the correlation coefficients between the expression levels determined using the two methods ranged from 0.94 to 0.99 (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Table 5. Selected contigs representing sweet cherry genes with predicted functions in cell wall modification, lipid metabolism, regulation of transcription, transport or other processes.

| Process or function | Contiga | Length (bp) | FPKM total | B2G best hit definition | Exob | Clusterc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_03454 | 2238d | 1440 | Endo-1,4-beta glucanase 10 | NG1-QT 44 | |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_06233 | 1789d | 170 | Polygalacturonase At1g48100 | NG1-QT 44 | |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_07062 | 1753d | 1622 | Probable pectate lyase 20 | NG1-QT 44 | |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_07115 | 848 | 4649 | Pectin methylesterase 3 | NG1-QT 44 | |

| Defense | Pa_11565 | 719d | 6818 | Snakin-1, precursor | NG1-QT 44 | |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_11433 | 2293d | 537 | Long chain acyl-CoA synthetase 1 | Exo | NG1-QT 44 |

| TF | Pa_22147 | 1828d | 521 | Transcription factor MYB76 | Exo | NG1-QT 44 |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_06731 | 1621d | 10 223 | Probable pectate lyase 5 | NG1-QT 43 | |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_00817 | 2053d | 2401 | Probable glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 8 | Exo | NG1-QT 43 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_01043 | 2508d | 2335 | Cytochrome P450 86A2 (ATT1) | Exo | NG1-QT 43 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_01742 | 2243d | 1935 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 10 | Exo | NG1-QT 43 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_01940 | 1555d | 4216 | GDSL esterase/lipase At2g04570 | Exo | NG1-QT 43 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_06204 | 2351d | 614 | Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 2 | Exo | NG1-QT 43 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_10336 | 1604 | 1524 | Protein HOTHEAD | Exo | NG1-QT 43 |

| TF | Pa_02691 | 991d | 8695 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor ERF023 | NG1-QT 43 | |

| TF | Pa_19618 | 1277d | 351 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor WIN1; SHN1 | Exo | NG1-QT 43 |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_10720 | 2015d | 784 | Endo-1,4-beta glucanase 11 | NG1-QT 39 | |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_00867 | 2120d | 2553 | BAHD acyltransferase DCR | Exo | NG1-QT 39 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_04572 | 1399d | 1908 | GDSL esterase/lipase; lithium tolerant lipase 1 | Exo | NG1-QT 39 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_14044 | 1946d | 447 | Putative aminoacrylate hydrolase RutD | Exo | NG1-QT 39 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_14662 | 1595d | 66 | Long-chain-alcohol O-fatty-acyltransferase WSD1 | Exo | NG1-QT 39 |

| TF | Pa_00973 | 1757d | 241 | AP2-like ethylene-responsive transcription factor | Exo | NG1-QT 39 |

| TF | Pa_23194 | 761 | 176 | Transcription factor WER; AtMYB66 | Exo | NG1-QT 39 |

| Transport | Pa_22556 | 1120d | 1708 | Uncharacterized GPI-anchored protein At1g27950 | Exo | NG1-QT 39 |

| TF | Pa_08841 | 1284d | 1090 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor SHINE 2 | Exo | NG1-QT 37 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_16669 | 1477d | 5943 | GDSL esterase/lipase At5g33370 | Exo | NG1-QT 36 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_22209 | 1638d | 645 | GDSL esterase/lipase At1g29670 | Exo | NG1-QT 36 |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_13423 | 887d | 25 363 | 21 kDa protein; pectin methylesterase inhibitor | NG1-QT 32 | |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_00478 | 2422d | 9571 | Protein WAX2 | Exo | NG1-QT 28 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_06166 | 2334d | 2920 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 6 | Exo | NG1-QT 28 |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_03006 | 2240d | 1688 | Probable pectate lyase 1 | NG1-QT 18 | |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_00883 | 2902d | 4084 | Endo-1,4-beta glucanase 6 | NG1-QT uncl. | |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_08907 | 2100d | 256 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 19 | Exo | NG1-QT uncl. |

| Hormone related | Pa_06858 | 1988 | 823 | ABA 8′-hydroxylase 4; Cytochrome P450 707A4 | NG3-QT 51 | |

| Transport | Pa_01687 | 2127d | 3767 | Polyol transporter 5; sugar-proton symporter PLT5 | Exo | NG3-QT 50 |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_03056 | 1375d | 766 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 33 | NG3-QT 46 | |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_04929 | 1898d | 6030 | Cytochrome P450 716B2; CYPA2 | Exo | NG3-QT 46 |

| TF | Pa_05584 | 2841 | 1563 | Homeobox-leucine zipper protein ANL2 | Exo | NG3-QT 38 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_05276 | 2709d | 884 | Protein WAX2 | Exo | NG3-QT 37 |

| Transport | Pa_06635 | 2918d | 701 | WBC11 | Exo | NG3-QT 37 |

| Transport | Pa_07137 | 2417d | 400 | ABC transporter G family member 15; AtWBC22 | Exo | NG3-QT uncl. |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_01792 | 2212d | 1802 | Pectin methylesterase 3 | NG4-QT 71 | |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_07321 | 1445 | 8058 | Xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein 28 | NG4-QT 71 | |

| TF | Pa_02092 | 2197d | 7361 | NAC domain containing protein 18 | NG4-QT 71 | |

| TF | Pa_06479 | 1790 | 6415 | Transcription factor MYB75 | NG4-QT 71 | |

| TF | Pa_00639 | 2490d | 9253 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor ERF071 | NG4-QT 70 | |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_09434 | 1516d | 6951 | Expansin A1 | NG4-QT 67 | |

| Cell wall modif. | Pa_14097 | 1560* | 10 667 | Probable pectate lyase 18 | NG4-QT 67 | |

| Other | Pa_02283 | 2605 | 2991 | CTP synthase 1 | NG4-QT 67 | |

| Transport | Pa_05395 | 1898d | 3094 | Polyol transporter 5; sugar-proton symporter PLT5 | Exo | NG4-QT 66 |

| Lipid metabolism | Pa_14729 | 1878* | 2560 | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 6 | Exo | NG4-QT uncl. |

Abbreviations: FPKM, fragments (reads) per kilobase of contig per million fragments mapped; uncl., unclustered.

See also Supplementary Table S4.

Exo, expression mostly in exocarp (FPKM values in mesocarp samples <1% of the total FPKM sum).

See Figure 6 and Supplementary Fig. S4.

Contig contains a complete open reading frame.

GO analysis detected over-represented GO terms assigned to the contigs in most of the large NG-QT clusters when compared to all Group 1F contigs. In cluster NG1-QT44 (Figure 6b), with expression maxima from 3 to 24 DAFB, over-represented GO terms were related to the cellular components chloroplast, ribosome and cell wall, and to the biological processes translation, protein-chromophore linkage and GDP-L-fucose biosynthetic process (Supplementary Table S8). Contigs homologous to cell wall modifying enzymes in this cluster included Pa_03454 (endo-1,4-β-glucanase), Pa_06233 (polygalacturonase), Pa_07062 (pectate lyase) and Pa_07115 (pectin methylesterase). Twenty-three of the 1363 contigs in cluster NG1-QT44 were exocarp-specific. Most of the over-represented GO terms associated with the exocarp-specific contigs were related to fatty acid metabolism. An example is the contig Pa_11433, whose best B2G hit was the long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase gene LACS1, involved in cutin and wax biosynthesis in Arabidopsis69 (Supplementary Table S4). Among the exocarp-specific contigs was also Pa_22147, a tentative MYB transcription factor gene with the highest similarity to the subgroup 9 of R2R3 MYB genes, known as regulators of epidermal cell differentiation and development.70 Its expression peaked at 10–17 DAFB. A similar temporal expression pattern has Pa_11565, a contig present in mesocarp at a very low level (FPKM value 24 DAFB in exocarp 10.3%±0.3%, in mesocarp 1.4% of total FPKM). Its best B2G hit was SNAKIN-1, a constitutive defense protein71 affecting cell division and cell wall composition in potato.68 A SNAKIN-1 homolog was also identified in developing tomato fruit, where it was 9.87-fold more abundant in the exocarp than in the mesocarp at the end of cell division stage.20

In cluster NG1-QT43, with average expression pattern similar to NG-QT44 but the expression maximum shifted to 24 DAFB (Figure 6b), the most specific, over-represented GO terms in the category biological process were folic acid metabolic process, photosynthesis and cutin biosynthetic process (Supplementary Table S8). An example of the photosynthesis-related genes in this cluster was the Top 40 contig Pa_16626, whose best B2G hit was ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase small chain. Cluster NG1-QT43 contained 56 exocarp-specific contigs. The most specific, over-represented GO terms assigned to the exocarp-specific contigs were related to lipid metabolism, in particular, cutin and wax biosyntheses (Supplementary Table S8). An example is the contig Pa_06204, which is a homolog of LACS2 in Arabidopsis and involved in the cutin biosynthesis in sweet cherry (Declercq, 2013, unpublished data). Other exocarp-specific contigs were also homologous to genes related to cuticle formation such as ATT1 (Pa_01043), HTH (Pa_10336), GPAT8 (Pa_00817), GDSL lipase (Pa_01940), KCS10 (Pa_01742) and the AP2/ERF family transcription factor WIN1 (Pa_19618) (Table 5). Most of these genes (except for the homologs of HTH and KCS10) were also among the ones identified previously as putatively involved in CM biogenesis in sweet cherry fruits, and their expression patterns here (Figure 6 and Supplementary Fig. S4B) were very similar to the ones reported.29 A highly abundant contig in this cluster was Pa_02691, an ERF transcription factor homolog. With FPKM values of 1451 (±39) in exocarp and 150 in mesocarp 24 DAFB, the sequence was much more abundant in the exocarp than in mesocarp, but it was not strictly exocarp-specific. In the functional category cell wall modifying enzymes, the contig Pa_06731, homologous to pectate lyase, was somewhat more expressed in the exocarp than in the mesocarp, with a maximum at 24 DAFB (exocarp, 1466±14 FPKM; mesocarp 852 FPKM). The corresponding pectate lyase may be involved in cell wall loosening and rearrangement during the rapid cell fruit growth occurring at this time. The finding is in line with the expression peak of the apple pectate lyase MdPL1 in growing apple.72 In our transcriptome, a total of eight contigs contained the pectate lyase/Amb allergen motif (IPR002022), four of which were predicted to represent full-length ORFs. Three of these contigs were in cluster NG1: The above mentioned Pa_07062 (NG1-QT44), Pa_06731, and, in cluster NG1-QT18, Pa_03006. The latter one had two prominent expression maxima, 24 and 66 DAFB, while the former ones were not expressed during Stage III. Interestingly, contig Pa_03006 was the best hit of a pectate lyase from sour cherry (PcPEL1, GenBank BG319625; 98% identity), which was highly expressed during the Stage III, and only slightly upregulated during Stage I in developing sour cherry.73

In cluster NG1-QT42, with expression maxima between 3 and 17 DAFB, the most specific, over-represented terms were related to ribosomes and translation. This is consistent with the high cell division activity characteristic for Stage I. Over-represented GO terms among the 29 exocarp-specific contigs of this cluster were carboxylesterase and tyrosine decarboxylase activities (Supplementary Table S8, Supplementary Table S4). All four sequences annotated with the GO term carboxylesterase activity were homologous to GDSL esterase/lipase and peaked 17 DAFB.

In cluster NG1-QT39 with expression maxima 17–24 DAFB the most specific, over-represented terms were hexose biosynthetic process, fatty acid biosynthetic process and Golgi apparatus. Among the 50 exocarp-specific contigs in this cluster was one specific, over-represented GO term: transferase activity, transferring acyl groups other than amino acyl group. The seven contigs annotated with this term included Pa_14662 (best B2G hit long-chain-alcohol O-fatty-acyltransferase WSD1, wax ester synthase/acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase) and Pa_00867 (best B2G hit BAHD acyltransferase DCR, DEFECTIVE IN CUTICULAR RIDGES), the former one possibly involved in wax and the latter one in cutin biosynthesis. Notable contigs in cluster NG1-QT39 further included two putative transcription factors (an AP2 family member, Pa_00973 and an MYB family member, Pa_23194, best B2G hit MYB66), a putative (hemi)cellulase (Pa_10720) and a lipid transport protein (Pa_22556, best BG2 hit uncharacterized GPI-anchored protein). The best PAVE hit of the latter contig was another assembled sweet cherry cDNA encoding a putative lipid transport protein, PaLTPG1 (GenBank JU090722), tentatively involved in cuticle deposition in sweet cherry fruit.29 Other exocarp-specific, putatively cuticle-related contigs in cluster NG1-QT39 included Pa_14044 and Pa_04572. The best BG2 hit of Pa_14044 was the putative aminoacrylate hydrolase RutD from Vitis vinifera, while the contig is also the best sweet cherry hit of the Arabidopsis protein BODYGUARD (BDG) (e-value 10×10−169, 61% amino-acid identity), an extracellular α/β superfamily hydrolase essential for cuticle formation.74 Pa_14044 was the only contig in the assembled sweet cherry fruit transcriptome to contain the multi domain PLN03087, ‘BODYGUARD 1 domain containing hydrolase’ (NCBI conserved domains search75). Contig Pa_04572, with the best B2G hit GDSL esterase/lipase LTL1, was the second best sweet cherry hit (e-value 10−157, 86% similarity) of the tomato CD1 protein, a GDSL lipase and putative cutin polymerase in tomato fruit epidermis.76,77 However, the best hit of tomato CD1 was Pa_16669 (e-value 10−159, 86% similarity), a member of cluster NG1-QT36 (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Cluster NG-QT36 also contained Pa_22209, another exocarp-specific GDSL lipase/esterase homolog with a full-length ORF.

In cluster NG1-QT37, over-represented GO terms were related to chloroplast. No over-represented GO terms were identified in the six exocarp-specific contigs of this cluster. A putatively cuticle-relevant, exocarp-specific contig in this cluster is Pa_08841 with the best B2G hit the ERF transcription factor SHINE2 from Arabidopsis, and the best PAVE hit the previously identified SHINE family transcription factor PaWINB, potentially involved in CM formation in the sweet cherry fruit.29 In total, we identified three contigs in the sweet cherry fruit transcriptome containing a full-length ORF, which most likely represent ERF family transcription factors from the SHINE clade, previously associated with regulation of cutin and wax deposition:78,79 Pa_08841, Pa_02691 and Pa_19618 (the latter two were in cluster NG-QT43). The recently characterized SlSHINE3,80 a regulator of cuticle development in tomato fruit and ortholog of Arabidopsis SHINE3 was most similar to Pa_08841 at the peptide level (69% positives, e-value 3×10−57) and to Pa_19618 at the nucleotide level (85% identity, e-value 3×10−32).

Smaller QT clusters in NG1 also contained several interesting contigs. For instance, potentially relevant for the cell wall architecture, Pa_13423 is a putative pectin methyl esterase inhibitor, highly abundant in the fruit with a maximum expression during 24–31 DAFB (NG1-QT32). A number of other contigs also shared high sequence similarity with pectin methyl esterase inhibitors, Pa_13423 being the most abundant one (total FPKM sum 25363). Indeed, its expression was much higher than that of any pectin methyl esterase homologs in the transcriptome. The unclustered contig Pa_00883 represents a putative (hemi)cellulase, present at a high level especially, while the rate of expansion growth was high (24 and 66 DAFB). Exocarp-specific contigs with probable relevance for wax biosynthesis included Pa_00478 (best hit WAX2, or CER1), Pa_06166 (3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 6) and the Top 40 contig Pa_29501 (non-specific lipid-transfer protein, allergen Pru av 3) in cluster NG1-QT28, and the unclustered contig Pa_08907 (3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 19). Contigs Pa_08907 and Pa_06166 were, together with Pa_01742 (NG1-QT43), the only three exocarp-specific contigs in Group 1F, which contained a full-length ORF and the InterPro motif very-long-chain 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (IPR012392), essential in wax biosynthesis. Pa_08907 was present at much lower levels than the other two but, interestingly, its expression peaked at equal levels during Stage I and during Stage III, while the two major KCS transcripts were abundant mainly during Stage I.

Based on the expression patterns, cluster NG1 was likely to contain most of the contigs with potential relevance to the process of our key interest, cuticle formation. Therefore, clusters NG3 and NG4 will be described in less detail than cluster NG1.

In the largest QT cluster of NG3 (NG3-QT51) the most specific, over-represented GO terms included photorespiration (or oxidative photosynthetic carbon pathway), terpene biosynthetic process and ABA 8′-hydroxylase activity. The most abundant contig with the latter GO term was Pa_06858, with an expression maximum from 38 to 45 DAFB. The contig is best hit of PacCYP707A2, the most abundant ABA 8′-hydroxylase transcript in the mesocarp of developing sweet cherry fruit.81 The expression patterns of the gene from Stage II to maturity in the exocarp of the cultivar Regina (this work) and in the mesocarp of cultivar Hongdeng81 were very similar. The consistent expression patterns underline the importance of this ABA degrading enzyme for the development of the sweet cherry fruit. Tightly regulated expression of genes in ABA turnover may account for the previously reported low and high ABA levels before and after onset of sweet cherry fruit ripening, respectively.81,82

The second largest QT cluster of NG3 (NG3-QT50) had a striking centroid expression pattern with maximum expression levels at the beginning of growth Stage II (31 DAFB). An exocarp-specific contig in this cluster, Pa_01687 (best B2G hit polyol transporter 5), with maximal expression from 31 to 45 DAFB (Supplementary Fig. S3b), might be useful as a molecular marker for Stage II. This contig is interesting for its putative function in sugar transport. Pa_01687 is the best hit of PcSOT2 (97% similarity, e-value 0.0), a sorbitol transporter from sour cherry fruit, also highly expressed during Stage II.83 Another putative sorbitol transporter sequence was nearly absent until 31 DAFB, but abundant thereafter to maturity (Pa_05395 in NG4-QT66). This developmental expression pattern is similar to the one of PcSOT1, the major sorbitol transporter accounting for sugar accumulation in maturing sour cherry.83 Like Pa_01687, the other major sorbitol transporter contig, Pa_05395 was exocarp specific (Supplementary Fig. S3b). The predicted peptide sequences of Pa_05395 and PcSOT1 were to 81% similar (e-value 0.0).

In the functional category cell wall metabolism, cluster NG3 includes contig Pa_03056 (NG3-QT46), homologous to a xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase protein, XTH33. The abundance of the contig increased sharply 45 DAFB, and stayed at a high level until 59 DAFB, after which it was detected at a very low level only (Supplementary Fig. S3b). The expression pattern suggests a specific role for the XTH gene in the cell wall rearrangements that preceed and accompany the increase in fruit growth rate (Figure 1a) and softening84 in Stage III. Exocarp-specific contigs with putative roles for cuticle formation in cluster NG3 included Pa_04929 (best hit cytochrome P450 716B2; with a total FPKM sum of 6030 a very highly abundant sequence), Pa_05584 (transhomeobox-leucine zipper protein ANL2), Pa_05276 (WAX2), Pa_06635 (ABC-transporter, WBC11) and Pa_07137 (ABC transporter). Pa_05584 was the best hit of the Arabidopsis HD-ZIP IV transcription factor gene ANL2 (ANHOCYANINLESS2), and of the tomato ANL2 homolog, CD2 (CUTIN DEFICIENT2). In Arabidopsis and tomato, these HD-ZIP IV factor are essential regulators of cutin, wax and anthocyanin levels.85–87 The expression pattern of Pa_05584 in sweet cherry fruit—exocarp-specific, high expression levels during stages II and III, lower but constant expression levels during Stage I—is consistent with roles in cuticular lipid and anthocyanin biosyntheses also for the sweet cherry fruit ANL2/CD2 homolog.

In cluster NG4, with expression maxima from mid-Stage II through Stage III, the largest cluster, QT71, contained 1956 contigs with mostly increasing expression levels from 31 DAFB to maturity and highest expression levels after 66 DAFB. Interesting sequences in this cluster included the putative cell wall related contigs Pa_01792 (best hit pectin methylesterase) and Pa_07321 (xyloglucan endotransglucosylase/hydrolase), tentatively active in the ripening associated softening of the fruit during Stage III.84 In this cluster, 79 contigs represent transcription factors, such as Pa_02092 (best B2G hit NAC domain containing protein) and Pa_06479 (best B2G hit MYB75). The former contig was highly abundant throughout Stage III, while the expression of the latter one increases sharply 66 DAFB and is at maximum from 80 to 87 DAFB. Pa_06479 is the most highly abundant MYB family transcription factor sequence in the sweet cherry fruit transcriptome (total FPKM sum 6415). The predicted peptide sequence is identical with GenBank ADY15304.1, defined as R2R3-MYB transcription factor from P. avium, and highly similar (85% similarity) with PavMYB10, another previously identified R2R3 MYB factor sequence from sweet cherry.88 PavMYB10 was identified as a main positive regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in the sweet cherry fruit.88,89 Consistent with such a function, the abundance of Pa_06479 increased with reddening of the fruit (Supplementary Fig. S3b and Figure 1a and 1c). The differences between the predicted amino acid sequences of Pa_06479 and PavMYB10 are similar to the differences in varying amino-acid residues among the MYB10 protein sequences from several rosaceous species.88

Cluster NG4-QT67, with centroid expression level elevated from 38 DAFB to maturity and an expression peak 66 DAFB, contains a putative pectate lyase, Pa_14097. With Pa_06731 (NG1-QT43), it is the most abundant pectate lyase transcript in the sweet cherry fruit transcriptome. It was the best hit of a ripening associated pectate lyase from apple (GenBank AY37687814) and the third best hit of the ripening associated pectate lyase PcPEL1 from sour cherry73 (best hit of PcPEL1 was Pa_03006, NG1-QT18; see above). Contig Pa_14097 was more expressed in the exocarp than in the mesocarp (80 DAFB exocarp, 1161±43 FPKM; mesocarp, 245 FPKM), suggesting that in sweet cherry fruit, this ripening associated pectate lyase is mostly relevant for the expansion growth of the exocarp cells. Altogether, the pectate lyase/Amb allergen motif (IPR002022) was identified in eight contigs, four of which were also predicted to contain a full-length ORF. Other contigs relevant for the cell wall architecture in cluster NG4-QT67 include Pa_09347 (best hit expansin) and Pa_44853 (probable rhamnose biosynthetic enzyme). Both contigs share with Pa_14097 the sharp peak in expression level 66 DAFB, consistent with functions in cell wall re-arrangements that enable the rapid expansion growth at this developmental stage.90 In addition to these cell wall-related contigs in cluster NG4-QT67, contig Pa_02283 (best hit cytidine triphosphate (CTP) synthase 1) also had a sharp expression peak 66 DAFB, with lower but still elevated expression from 73 to 87 DAFB. In eukaryotic cells, CTP is required for phospholipid biosynthesis and CTP synthase is the key enzyme in the process.91,92 A function of the putative CTP synthase encoded by Pa_02283 in phospholipid biosynthesis in sweet cherry fruit is consistent with a high demand for membrane lipids during the maximum rate of fruit surface expansion 66 DAFB.

Further contigs from cluster NG4 selected for Table 5 encode enzymes involved in cuticular lipid biosynthesis, transcription factors and a sugar transporter. The unclustered, exocarp specific contig Pa_14729 encodes a putative glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase (GPAT); its best B2G hit was GPAT6. The contig has two expression maxima, 17–24 DAFB and 66–87 DAFB. In Arabidopsis, GPAT6 functions in cutin biosynthesis in petals and sepals.93 The exocarp specific expression pattern with the peak during the highest rate of cuticle deposition (24 DAFB) in sweet cherry fruit is consistent with a function in the cutin biosynthetic pathway. Along these lines, the second maximum during Stage III is consistent with the low but detectable cuticle deposition rate at this late stage (Figure 1b) and with the increased amounts of the main cutin constituents, 9(10)-hydroxy-hexadecane-1,16-dioic acid and 9(10),16-dihydroxy-hexadecanoic acid, at maturity as compared to 22 DAFB.8

Conclusions

The sweet cherry fruit transcriptome database P.avium_v2.0 consists of a comprehensive set of assembled, annotated sequences representing genes that contribute to the fruit skin development and their detailed expression patterns over time (the sequences, annotation and expression data for all contigs are available as Supplementary Data S1 and Supplementary Table S4). The genome-wide analyses indicate tight developmental regulation of genes functioning in diverse processes such as transcriptional regulation, sugar transport, lipid metabolism and cell wall rearrangements. The high temporal resolution of the expression patterns presented here reveals finely tuned developmental specialization of different members of gene families. Moreover, the de novo assembled sweet cherry fruit transcriptome with 7760 full-length protein coding sequences and over 20 000 other, annotated cDNA sequences together with their developmental expression patterns are expected to accelerate molecular research on this important tree fruit crop with up to now only little genomic resources.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support (Grant AL1373_1-1) and Thorben Sprink for sampling of the fruit and isolation of RNA for the RNA-seq analyses.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Esau K. Anatomy of Seed Plants. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Baur P, Stulle K, Schönherr J, Uhlig B. [Absorption of radiation in the UV-B to blue light range by leave cuticles of selected crop plants].Gartenbauwissenschaft 1998; 63: 145–152. German [Google Scholar]

- Martin JT, Juniper BE. The Cuticles of Plants. Edinburgh: Edward Arnold Ltd, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Kerstiens G. Plant Cuticles—An Integrated Functional Approach. Oxford: BIOS Scientific Publishers, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lalel HJD, Singh Z, Tan SC. Distribution of aroma volatile compounds in different parts of mango fruit. J Hort Sci Biotechnol 2003; 78: 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Knoche M, Beyer M, Peschel S, Oparlakov B, Bukovac MJ. Changes in strain and deposition of cuticle in developing sweet cherry fruit. Physiol Plant 2004; 120: 667–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leide J, Hildebrandt U, Reussing K, Riederer M, Vogg G. The developmental pattern of tomato fruit wax accumulation and its impact on cuticular transpiration barrier properties: effects of a deficiency in a beta-ketoacyl-coenzyme A synthase (LeCER6). Plant Physiol 2007; 144: 1667–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peschel S, Franke R, Schreiber L, Knoche M. Composition of the cuticle of developing sweet cherry fruit. Phytochemistry 2007; 68: 1017–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DS, Davies WJ, Ho LC. Regulation of tomato fruit growth by epidermal cell wall enzymes. Plant Cell Environ 1998; 21: 589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Bargel H, Neinhuis C. Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) fruit growth and ripening as related to the biomechanical properties of fruit skin and isolated cuticle. J Exp Bot 2005; 56: 1049–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Tomato Genome Consortium. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature 2012; 485: 635–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Sugimoto N, Larson MD, Beaudry R, van Nocker S. Identification of genes with potential roles in apple fruit development and biochemistry through large-scale statistical analysis of expressed sequence tags. Plant Physiol 2006; 141: 811–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen BJ, Thodey K, Schaffer RJ et al. Global gene expression analysis of apple fruit development from the floral bud to ripe fruit. BMC Plant Biol 2008; 8: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa F, Alba R, Schouten H et al. Use of homologous and heterologous gene expression profiling tools to characterize transcription dynamics during apple fruit maturation and ripening. BMC Plant Biol 2010; 10: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva FG, Iandolino A, Al-Kayal F et al. Characterizing the grape transcriptome. Analysis of expressed sequence tags from multiple Vitis species and development of a compendium of gene expression during berry development. Plant Physiol 2005; 139: 574–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilati S, Perazzolli M, Malossini A et al. Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of grapevine berry ripening reveals a set of genes similarly modulated during three seasons and the occurrence of an oxidative burst at vèraison. BMC Genomics 2007; 8: 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trainotti L, Bonghi C, Ziliotto F et al. The use of microarray µPEACH1.0 to investigate transcriptome changes during transition from pre-climacteric to climacteric phase in peach fruit. Plant Sci 2006; 170: 606–613. [Google Scholar]

- Manganaris GA, Rasori A, Bassi D et al. Comparative transcript profiling of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) fruit development and on-tree ripening. Tree Genet Genomes 2011; 7: 609–616. [Google Scholar]

- Yin YX, Zhang XW, Fang YJ et al. High-throughput sequencing-based gene profiling on multi-staged fruit development of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera, L.). Plant Mol Biol 2012; 78: 617–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire-Chamley M, Petit J, Garcia V. Changes in transcriptional profiles are associated with early fruit tissue specialization in tomato. Plant Physiol 2005; 139: 750–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]