Abstract

The federal 340B program gives participating hospitals and other medical providers deep discounts on outpatient drugs. Named for a section of the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992, the program’s original intent was to help low-income and uninsured patients. But the program has come under scrutiny by critics who contend that some hospitals exploit the drug discounts to generate profits instead of either investing in programs for the poor or passing the discounts along to patients and insurers. We examined whether the program is expanding in ways that could maximize hospitals’ ability to generate profits from the 340B drug discounts. We matched data for 960 hospitals and 3,964 affiliated clinics registered with the 340B program in 2012 with the socioeconomic characteristics of their communities from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. We found that hospital-affiliated clinics that registered for the 340B program in 2004 or later served communities that were wealthier and had higher rates of health insurance compared to communities served by hospitals and clinics that registered for the program before 2004. Our findings support the criticism that the 340B program is being converted from one that serves vulnerable patient populations to one that enriches hospitals and their affiliated clinics.

Section 340B of the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992 was intended to give assistance to low-income and uninsured patients.1 The 340B program gives registered “340B entities” such as hospitals and other medical care providers—including federally qualified health centers and state AIDS Drug Assistance Programs—access to deep discounts on outpatient drugs similar to those offered through the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, which was created by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990.

Participation in the 340B program has increased substantially in recent years. In 2011 there were 16,500 340B entity sites that were affiliated with approximately 3,200 unique 340B entities. That is roughly double the number of sites reported in 2001.1

As the number of sites qualifying for the 340B discounts has grown, the program has come under increased scrutiny. Critics contend that this growth is largely driven by hospitals seeking to exploit the availability of 340B drug discounts to generate profits.

340B hospitals can generate profits by prescribing drugs to patients who have private insurance or Medicare.2 Other participating medical providers are required to pass along the discounts to patients and to provide annual reports about their service to vulnerable populations to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), which oversees the 340B program. However, 340B hospitals are not required to pass along their discounts to patients or insurers or to demonstrate their investments in outpatient programs for the poor. Consequently, these providers can generate 340B profits by pocketing the difference between the discounted price that they paid for the drugs and the higher reimbursement paid by insurers and patients.

“Hospitals can elect to sell all of their 340B drugs to only fully insured patients while not passing any of the deeply discounted prices to the most vulnerable, the uninsured. This is contrary to the purpose of the 340B program since much of the benefit of the discounted drugs flows to the covered entity rather than to the vulnerable patients that the program was designed to help,” Sen. Charles Grassley (R-IA) wrote in a 2013 letter to Mary Wakefield, administrator of HRSA.3

In 2012 one 340B entity, Duke University Hospital, reported five-year profits of $282 million accrued through its outpatient departments and affiliated clinics as a result of its participation in the 340B program.4 Another report suggested that profits generated through the prescribing of a single medical oncologist who practices at an outpatient clinic affiliated with a 340B hospital could reach $1 million per year, when the oncologist administered drugs obtained at 340B discounted prices to treat fully insured patients.5

It is logical to assume that as 340B hospitals consider the pros and cons of expansion, the potential profit might lead them to expand into areas that serve more affluent and better insured patients, even if this is counter to the 340B program’s goals of improving care and access for low-income and uninsured patients. Strategic behavior by these hospitals could take one of three forms: A hospital could decide to provide outpatient service to new communities where patients have higher incomes and greater access to insurance, compared to communities served by the hospital in earlier years; to pursue affiliations with outpatient clinics or open outpatient clinics in such new communities; or both. The wide implementation of these strategies would enhance the profitability of participating 340B hospitals without advancing the core goals of the program.

We conducted an empirical analysis to determine whether the expansion of the 340B program has been associated with a shift away from its core focus on low-income and underinsured communities and toward communities whose residents generally have higher incomes and greater access to insurance. Specifically, we focused on 340B hospitals that also participated in Medicare’s disproportionate-share hospital (DSH) program. This program provides hospitals with increased payments for services based on a formula that takes into account the proportion of low-income and uninsured patients treated as inpatients at those facilities.

If, compared to previously registered 340B hospitals, newly registered hospitals served similar or more vulnerable communities, newly affiliated clinics cared for similar or more vulnerable communities, or both, that would be evidence that the program’s expansions have been consistent with Congress’s original intent.

Study Data And Methods

This is an observational study that used nationally representative data on 340B program participants matched to data from the US Census Bureau6 on communities’ socioeconomic characteristics. We employed a cross-sectional inter-temporal design. This allowed us to assess the 2012 socioeconomic characteristics of the communities served by 340B hospital entities that received DSH payments (which we refer to below as 340B DSH hospitals) and their affiliated clinics in relation to the year when these providers first registered for the 340B program. The study design also allowed us to determine if expansions of the program at the level of the hospital, affiliated clinic, or both were trending toward serving more affluent communities of patients instead of the low-income populations that the program was intended to help.

Using a single year to assess the socioeconomic characteristics of all of the communities in our study has strengths and limitations. Specifically, the cross-sectional analytic approach ensures that our results are not an artifact of the passing of time or of shifting socioeconomic characteristics in particular communities. The approach also takes advantage of a specific program requirement: Every year, each 340B entity must be recertified for the program. For a hospital participating in Medicare’s DSH program, certification requires that the current patient population served by its inpatient service meet 340B program requirements based on data reported in the hospital’s Medicare cost reports. Hospitals that do not meet these requirements annually are terminated from the program, along with their affiliated clinics.

However, using area-level measures of a community’s socioeconomic characteristics limited our ability to determine the makeup of the population that a 340B entity serves. This limitation is a classic form of mismeasurement: It weakened our ability to detect the patterns of 340B program registrations and clinic affiliations that we hypothesized existed over time, without introducing directional bias.

The online Appendix7 provides details about the data sources that we employed, our outcome variable definitions, the empirical methods that we used, and the sensitivity analyses that we performed.

Study Results

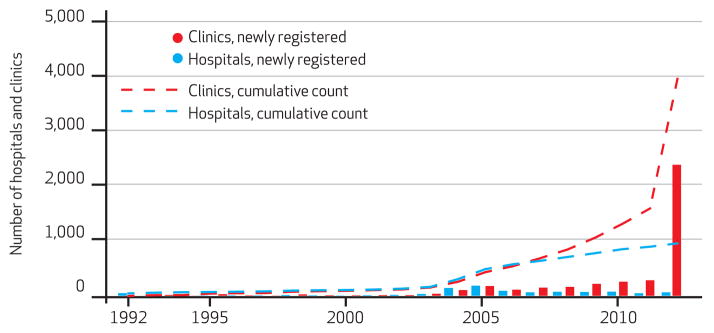

In 2012 there were 960 340B DSH hospitals (Exhibit 1). The number of newly registered 340B DSH hospitals has steadily increased since the 340B program’s inception in 1992. However, the number began to increase at a higher rate starting in 2003. In 2012 there were 3,964 out-patient clinics affiliated with the 340B DSH hospitals. The number of clinics newly registered with the 340B program has increased exponentially since 1993, numbering 3,964 in 2012. In 2007 the number of affiliated clinics in the program (689) surpassed the number of DSH hospitals in the program (641).

Exhibit 1.

Numbers Of Disproportionate-Share Hospitals And Their Affiliated Outpatient Clinics In The 340B Program, 1992–2012

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 340B provider list maintained by the Office of Pharmacy Affairs in the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Fifty-three percent of 340B DSH hospitals (510 out of 960) had at least one affiliated clinic in 2012 (data not shown). On average, these 510 hospitals had nine affiliated clinics each (median: 4; range: 1–140).

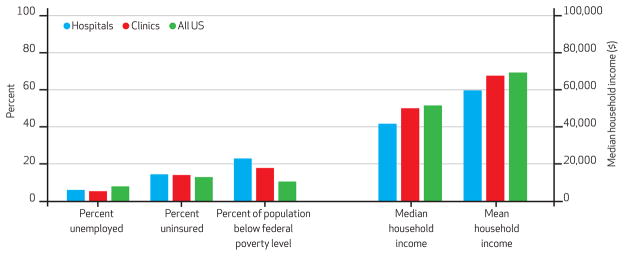

In 2012 health uninsurance rates were lower (p < 0.0001) in communities with affiliated clinics, compared to communities with 340B DSH hospitals (Exhibit 2). Communities with 340B DSH hospitals had significantly higher poverty rates and lower unemployment and mean and median household incomes, compared to national averages (p < 0.01). The socioeconomic characteristics of communities with affiliated clinics were significantly more similar to national averages (p < 0.01). The differences between communities with 340B DSH hospitals and those with affiliated clinics were also significant (p < 0.01).

Exhibit 2.

Socioeconomic Characteristics Of Communities Served By 340B Disproportionate-Share Hospitals And Served By Hospital-Affiliated Outpatient Clinics Compared To Communities In All US ZIP Code Tabulation Areas

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 340B provider list maintained by the Office of Pharmacy Affairs in the Health Resources and Service Administration; US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey demographic and housing estimates, 2012; and US Census Bureau’s Small Area Health Insurance Program, August 2013. NOTES Percent unemployed, uninsured, and below federal poverty level relate to the left-hand y axis. Household income relates to the right-hand y axis.

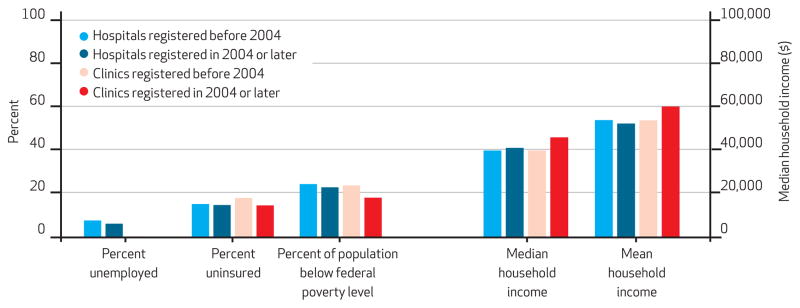

Generally, DSH hospitals that registered for the 340B program in 2004 or later served communities with fewer low-income people (p < 0.05), compared to DSH hospitals that registered before 2004 (Exhibit 3). Communities with hospitals that registered before 2004 and those with hospitals that registered in later years did not differ significantly in terms of uninsurance rates or mean and median household incomes. Clinics affiliated with 340B entities that registered for the 340B program in 2004 or later served wealthier communities with higher levels of insurance (p < 0.01), compared to clinics that registered before 2004.

Exhibit 3.

Socioeconomic Characteristics Of Communities Served By Disproportionate-Share Hospitals And By Hospital-Affiliated Outpatient Clinics, By Time Of Registration For The 340B Program

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 340B provider list maintained by the Office of Pharmacy Affairs in the Health Resources and Service Administration; US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey demographic and housing estimates, 2012; and US Census Bureau’s Small Area Health Insurance Program, August 2013. NOTES Percent unemployed, uninsured, and below federal poverty level relate to the left-hand y axis. Household income relates to the right-hand y axis. Communities with clinics that registered for the 340B program both before 2004 and later had unemployment rates of less than 1 percent.

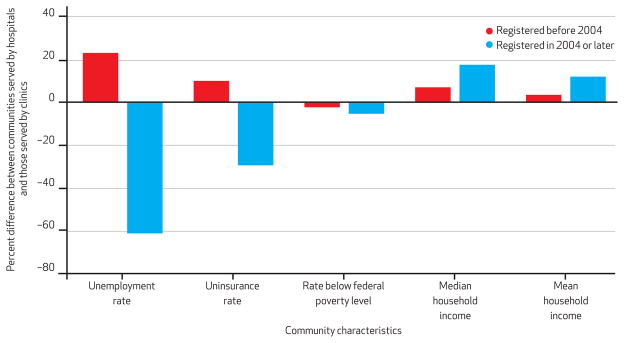

Furthermore, when we compared communities served by hospitals and those served by clinics, we found that facilities registering in 2004 or later differed from those registering before 2004 (Exhibit 4). Relative to communities served by hospitals registering in the later time period, communities served by clinics had lower rates of uninsurance, for example, but the opposite was true with facilities registering in the earlier time period. In general, hospitals that registered in 2003 or before had clinics that served significantly poorer communities than their parent institutions, compared to facilities that registered after 2004 (p < 0.01).

Exhibit 4.

Socioeconomic Characteristics Of Communities Served By Hospital-Affiliated Clinics In Comparison To Characteristics Of Communities Served By Disproportionate-Share Hospitals, By Time Of Registration For The 340B Program

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 340B provider list maintained by the Office of Pharmacy Affairs in the Health Resources and Service Administration; US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey demographic and housing estimates, 2012; and US Census Bureau’s Small Area Health Insurance Program, August 2013. NOTES The figure shows how communities served by clinics compared to those served by hospitals. For example, the unemployment rate in communities served by clinics that registered before 2004 was 23 percent greater than the unemployment rate in communities served by hospitals that registered before 2004. In contrast, the rate in communities served by clinics that registered later was 61 percent less than the rate in communities served by hospitals that registered later.

These findings were robust in regressions that employed continuous time measures and alternative years as the cutoff point. Notably, differences with clinics’ parent 340B hospitals in terms of socioeconomic characteristics of the communities served were increasingly stark for clinics that joined the 340B program in 2011 and 2012, compared to those that joined before 2004 (p < 0.01; for percentage differences in community socioeconomic characteristics between affiliated clinics and DSH hospitals by year of 340B registration, see Appendix Exhibit A1).7

In addition, our results were robust in regressions that used the Primary Care Service Area as an alternative geographic unit of analysis (results available upon request from the corresponding author). Our findings were also consistent with an additional comparison of variables reported on each 340B hospital’s 2012 Medicare cost report, which HRSA uses to determine the hospitals’ registration and annual certification for the 340B program (for a comparison of hospital characteristics reported on Medicare cost reports from hospitals that qualified for the 340B program before 2004 and those that qualified later, see Appendix Exhibit A2).7

Discussion

The primary purpose of the 340B program was to give assistance to low-income and uninsured patients.1 Since its inception, the program has experienced expansions. However, we observed significant growth in the number of newly registered 340B DSH hospitals and exponential growth in the number of outpatient clinics affiliated with them since 2004.

We focused on whether these expansions have been associated with a shift away from the program’s core focus on low-income and uninsured populations. We found that 340B DSH hospitals serve communities that are poorer and have higher uninsurance rates than the average US community. However, beginning around 2004, newly registered 340B DSH hospitals have tended to be in higher-income communities, compared to hospitals that joined the 340B program earlier.

We also found that, compared to 340B DSH hospitals, their affiliated clinics tended to serve communities with socioeconomic characteristics that were more similar to the average US community: The clinics served communities with lower poverty rates and higher mean and median income levels than their 340B DSH hospital parents did. These results suggest that the expansions among 340B DSH hospitals run counter to the program’s original intention.

Our findings are consistent with recent complaints by stakeholders and media reports suggesting that the 340B program is being converted from one that serves vulnerable communities to one that enriches participating hospitals and the clinics affiliated with them.3–5 Other recent analyses have suggested that hospitals receiving DSH payments are shifting some specialty care from the inpatient to the outpatient setting, where drug discounts gained from participation in the 340B program may generate increased profits.8–10

Our results are consistent with another examination of the recent geographical patterns of merger and acquisition activities occurring between hospitals and clinics in twelve US communities. Emily Carrier and coauthors report that hospitals are increasingly pursuing targeted, geographic service expansion to “capture” well-insured patients.11 An important future empirical analysis would examine whether 340B DSH hospitals are pursuing such activities at a different rate, are targeting different patient populations, or both, compared to hospitals that do not participate in the 340B program.

More broadly, our findings suggest that gaining access to 340B drug discounts may act as one motivating rationale for the affiliations and mergers among hospitals and outpatient physician practices that are becoming increasingly common in the United States.12–14 There are likely multiple reasons for such mergers, acquisitions, and affiliations that linked hospitals and out-patient clinics during this period.

From the hospitals’ perspective,15 the goals of these activities may include improving payer mix, becoming better able to compete with other hospitals, and avoiding competition from specialist-owned ambulatory surgery centers;16 cooperating on quality improvement measures;17 and increasing leverage with health plans.18 Physicians may also wish to pursue these relationships to improve their working hours or referral patterns and to reduce significant financial risks.

In this context, the potential for profit derived from 340B drug purchases should be most concentrated among specialty outpatient practices—including those in oncology, neurology, and ophthalmology—that heavily use costly prescription drugs to care for their patients. It is beyond the scope of our analysis to test this hypothesis empirically. However, we surveyed the trade literature on documented shifts in care and in merger and acquisition activities among out-patient specialty care providers. We found evidence that supported the hypothesis for oncologists.19–22 A 2012 report by Elaine Towle and coauthors suggests that the share of physician-owned private practices in oncology declined 10 percentage points between 2010 and 2011, while merger and acquisition activities between community oncology practices and hospitals increased substantially.22

Conclusion

Few data are available to systematically assess the impact that the expansion of 340B-qualified hospitals may be having on medical care spending, access, and quality. Most previous literature on these effects has drawn on news reports or government audits that featured selected institutions.23 In previous work we argued that these expansions are likely raising chemotherapy spending and prices for patients and insurers, and providing limited gain to the poor and uninsured.2 The pursuit of timely, transparent, and national assessments of whether and how the activities of 340B hospitals and their affiliated clinics are benefiting the populations originally targeted by the Veterans Health Care Act is an important policy goal.

Acknowledgments

Rena Conti received support from the National Cancer Institute (Grant No. K07-CA138906). The opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and not that of the University of Chicago, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, or the National Cancer Institute. The authors thank Ernst R. Berndt for comments and Geoffrey Schnorr and Ali Bonakdar Tehrani for expert research assistance.

Contributor Information

Rena M. Conti, Email: rconti@uchicago.edu, Assistant professor of health policy and economics in the Departments of Pediatrics and Health Studies at the University of Chicago, in Illinois

Peter B. Bach, Director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, in New York City

NOTES

- 1.Government Accountability Office. Drug pricing: manufacturer discounts in the 340B program offer benefits, but federal oversight needs improvement [Internet] Washington (DC): GAO; 2011. Sep, [cited 2014 Aug 28]. Available from: http://gao.gov/assets/330/323702.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conti RM, Bach PB. Cost consequences of the 340B drug discount program. JAMA. 2013;309(19):1995–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grassley CE. Letter to Mary K. Wakefield [Internet] Washington (DC): Senate Committee on the Judiciary; 2013. Mar 27, [cited 2014 Aug 28]. Available from: http://www.grassley.senate.gov/sites/default/files/about/upload/2013-03-27-CEG-to-HRSA-340B-Oversight-3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander A, Garloch K, Neff J. Nonprofit hospitals thrive on profits. Charlotte Observer. 2012 Apr 21; [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollack A. Dispute develops over discount drug program. New York Times. 2013 Feb 12; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Census Bureau. American Fact-Finder: community facts [Internet] Washington (DC): Census Bureau; [cited 2014 Aug 28]. Available from: http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. [Google Scholar]

- 7.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 8.Garloch K, Alexander A. Oncologists struggle to stay independent. Charlotte Observer. 2012 Sep 22; [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitch K, Pyenson B. Site of service cost differences for Medicare patients receiving chemotherapy [Internet] Seattle (WA): Milliman; 2011. Oct 19, [cited 2014 Aug 28]. Available from: http://publications.milliman.com/publications/health-published/pdfs/site-of-service-cost-differences.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moran Company. Results of analyses for chemotherapy administration utilization and chemotherapy drug utilization, 2005–2011 for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries [Internet] Arlington (VA): Moran Company; 2013. May 29, [cited 2014 Aug 28]. Available from: http://glacialblog.com/userfiles/76/Moran_Site_Shift_Study_P1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrier ER, Dowling M, Berenson RA. Hospitals’ geographic expansion in quest of well-insured patients: will the outcome be better care, more cost, or both? Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(4):827. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker LC, Bundorf MK, Kessler DP. Vertical integration: hospital ownership of physician practices is associated with higher prices and spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(5):756–63. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutler DM, Scott Morton F. Hospitals, market share, and consolidation. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1964–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Welch WP, Cuellar AE, Stearns SC, Bindman AB. Proportion of physicians in large group practices continued to grow in 2009–11. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(9):1659–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casalino LP, November EA, Berenson RA, Pham HH. Hospital-physician relations: two tracks and the decline of the voluntary medical staff model. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27(5):1305–14. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kocher R, Sahni NR. Hospitals’ race to employ physicians—the logic behind a money-losing proposition. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1790–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1101959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berenson RA, Ginsburg PB, May JH. Hospital-physicians relations: cooperation, competition, or separation? Health Affairs (Millwood) 2007;26(1):w31–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuellar AE, Gertler PJ. Strategic integration of hospitals and physicians. J Health Econ. 2006;25(1):1–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levinson DR. Review of selected physician practices’ procedures for tracking drug administration costs and ability to purchase cancer drugs at or below Medicare reimbursement rates [Internet] Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General; 2007. Jul, [cited 2014 Aug 28]. (Report No. A-09-05-00066). Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oas/reports/region9/90500066.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barr TR, Towle EL. Oncology practice trends from the National Practice Benchmark, 2005 through 2010. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(5):286–90. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barr TR, Towle EL. Oncology practice trends from the National Practice Benchmark. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(5):292–7. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Towle EL, Barr TR, Senese JL. National Oncology Practice Benchmark, 2012 report on 2011 data. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(6):51s–70s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castellon YM, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Masatsugu M, Contreras R. The impact of patient assistance programs and the 340B Drug Pricing Program on medicaton cost. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(2):146–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]