Abstract

Introduction

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (NCCCP) funds states, the District of Columbia, tribal organizations, territories, and jurisdictions across the USA develop and implement jurisdiction-specific comprehensive cancer control (CCC) plans. The objective of this study was to analyze NCCCP action plan data for incorporation and appropriateness of cancer survivorship-specific goals and objectives.

Methods

In August 2013, NCCCP action plans maintained within CDC’s Chronic Disease Management Information System (CDMIS) from years 2010 to 2013 were reviewed to assess the inclusion of cancer survivorship objectives. We used the CDMIS search engine to identify “survivorship” within each plan and calculated the proportion of programs that incorporate cancer survivorship-related content during the study period and in each individual year. Cancer survivorship objectives were then categorized by compatibility with nationally accepted, recommended strategies from the report A National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies (NAP).

Results

From 2010 to 2013, 94 % (n=65) of NCCCP action plans contained survivorship content in at least 1 year during the time period and 38 % (n=26) of all NCCCP action plans addressed cancer survivorship every year during the study period. Nearly 64 % (n=44) of NCCCP action plans included cancer survivorship objectives recommended in NAP.

Conclusion

Nearly all NCCCP action plans addressed cancer survivorship from 2010 to 2013, and most programs implemented recommended cancer survivorship efforts during the time period.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

NCCCP grantees can improve cancer survivorship support by incorporating recommended efforts within each year of their plans.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Cancer survivors, Comprehensive cancer control

Introduction

A cancer survivor is any person who has been diagnosed with cancer from the time of diagnosis throughout the person’s life [1, 2]. There are approximately 14 million cancer survivors in the USA, and the population is projected to exceed 18 million by 2022, primarily due to an aging population, improvements in treatment, and increases in early diagnoses [3]. Due to this large and growing population, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has dedicated a substantial amount of public health resources to improving the life of cancer survivors in the USA. In 2004, CDC developed a National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship: Advancing Public Health Strategies (NAP) [4], a publication cosponsored by Livestrong (formerly the Lance Armstrong Foundation). The NAP was developed to inform the general public, policymakers, survivors, providers, and others about ways that public health can address cancer survivorship. Objectives included in the NAP are to: “establish a solid base of applied research and scientific knowledge on the ongoing physical, psychological, social, spiritual, and economic issues facing cancer survivors” and “implement effective and proven programs and policies to address cancer survivorship more comprehensively” [4]. Since the development of NAP, CDC research efforts have focused on the long-term adverse physical, psychosocial, and financial effects from a cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment [2, 5–7]. For example, in 2012, CDC led the first state-based descriptive analysis of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data among cancer survivors, including demographic characteristics and health behaviors, as well as cancer treatment history and health insurance coverage of treatment [2]. The study revealed that a large proportion of cancer survivors has comorbid conditions, currently smoke, do not participate in any leisure time physical activity, and are obese. Furthermore, many are not receiving recommended preventive care, including cancer screening and influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations [2]. Our recent research identifies gaps in meeting the needs of cancer survivors that can be addressed through public health efforts and support.

CDC’s National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program (NCCCP) funds US states, the district of Columbia (DC), tribes and tribal organizations, selected territories, and associated Pacific Island Jurisdictions to develop and implement comprehensive cancer control (CCC) plans [8, 9], all of which include specific goals and objectives to reduce the burden of cancer. In 2010, the NCCCP established six program priorities, one of which is to address the needs of cancer survivors [10]. Programs submit action plans, reports, and other materials to CDC as part of standard reporting requirements. This information is used in part to evaluate program activities within key areas of interest. Cancer plans have previously been evaluated for interventions in radon, tobacco control, and gynecologic, colorectal, and liver cancers [10–14].

Since cancer survivorship is a program priority, CDC researchers conducted an evaluation of all program activities. To determine the extent to which the NCCCP currently addresses needs among cancer survivors, we undertook an evaluation of current survivorship activities. We also determined whether these activities are consistent with strategies provided in the NAP. Our analyses include action plans provided by all 50 states, the district of Columbia, and US territories and tribal jurisdictions funded by NCCCP. Since adequately addressing the needs of cancer survivors is an increasingly important public health area, we aim to identify opportunities in these plans that will help states, territories, tribes, and jurisdictions meet the needs of the growing cancer survivor population. This is the first assessment of cancer survivorship interventions found in NCCCP action plans.

Methods

In August 2013, NCCCP action plans for 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013 were obtained from each of the 50 US states, the district of Columbia, territories, tribes, and Pacific Island Jurisdictions (n=69) to assess inclusion of cancer survivorship objectives. For some analyses, years were combined to represent cancer survivorship activities conducted during NCCCP funding periods 2010–2011 and 2012–2013. Each CCC action plan is housed in CDC’s Chronic Disease Management Information System (CDMIS), which was developed to collect programmatic data from selected CDC chronic disease program awardees. NCCCP was an inaugural member of CDMIS, and the NCCCP module systematically captures data from all NCCCP awardees about staff, CCC coalition members, resources (e.g., leveraged financial resources, etc.), and planning tools (e.g., surveillance data sources and evaluation plans). Annual action plans that include objectives linked to overall 5-year project period objectives and describe programmatic work that form the basis for interim and annual progress reports are also included in CDMIS. Every year, action plans are entered into the web-based CDMIS, which we used to analyze all 69 CCC program action plans. Since cancer survivorship was established as a priority in 2010, each plan included updated information for 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013.

An action plan has four sections: project period objectives, annual objectives, annual activities, and annual products. Information in the plans related to objectives generally includes description, targets, baseline estimates, timeframe, and activities. CDMIS contains a search feature that was used to identify, abstract, and review cancer survivorship-related content. Preformed “survivorship” search options were available in the project period objectives, annual objectives, and annual activities sections of each action plan and were used to search content. In addition, free text keyword searches using the term survivorship were conducted in all four parts of the action plan. Several abstraction tools were created in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) through a function in the CDMIS database to collect and review data. Abstraction was done on plans from each calendar year (2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013).

After data abstraction, we applied dichotomous indicators “yes or no” to each of the program plans. We designated “yes” for programs that listed survivorship as a project period objective, annual objective, priority area, or smart statement. We further stratified results based on four core public health components based on recommendations from NAP [4]: 1) surveillance and applied research; 2) communication, education, and training; 3) programs, policies, and infrastructure; and 4) access to quality care and services. A specific activity could meet criteria for fulfilling more than one of the four components. Three of the most common activities per component were identified by reviewing the activities and documenting trends. A specific example of each common activity was randomly selected to share what CCC programs are conducting in the area of survivorship.

All plans were abstracted by one investigator, with review, categorization, and concurrence by others.

Results

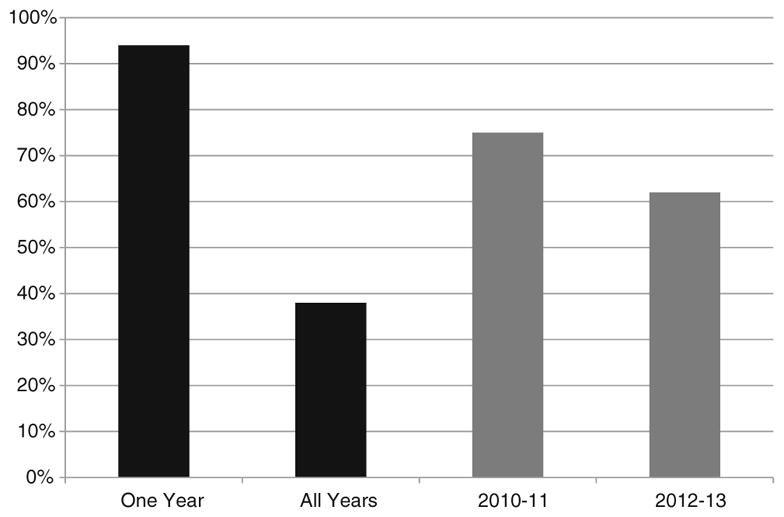

From 2010 to 2013, 94 % (n=65) of NCCCP grantees addressed cancer survivorship within their action plans (Fig. 1). Approximately 38 % (n=26) of NCCCP grantees addressed cancer survivorship during every year of the study period. A total of 75 % (n=52) of programs addressed survivorship during funding period 2010–2011, which decreased to 62 % (n=43) in funding period 2012–2013.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of grantees reporting survivorship activities in CDC’s National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program by year and funding period (2010–2013). One year=survivorship activities are incorporated in at least 1 year of the study period (2010, 2011, 2012, or 2013). All years= survivorship activities are incorporated in every year of the study period (2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013). 2010–2011 and 2012–2013 represent funding periods for National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program activities

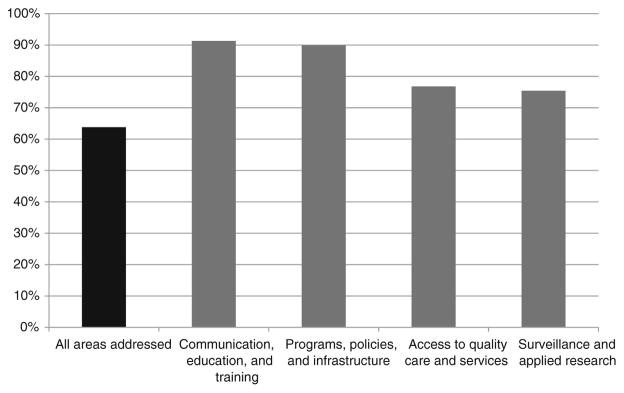

A total of 64 % (n=44) of all NCCCP action plans included recommended cancer survivorship objectives from the NAP (Fig. 2). The most commonly incorporated survivorship objective was providing “communication, education, and training” (91 %, n=63), followed by developing “programs, policies, and infrastructure” (90 %, n=62), ensuring “access to quality care and services” (77 %, n=53), and supporting “surveillance and applied research” (75 %, n=52).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of CDC National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program Grantees reporting cancer survivorship strategies consistent with the Cancer Survivorship National Action Plan, 2010–2013. The figure reflects programs that meet four core public health components used nationally to prioritize cancer survivorship needs and propose strategies within the National Action Plan for Cancer Survivorship [14]

Examples of specific activities implemented to meet survivorship goals varied by program (Table 1). Many programs incorporated continued the use of BRFSS data to meet the surveillance and applied research objective. Fact sheets, which explain a cancer diagnosis, were commonly used to meet communication, education, and training objectives. Some programs incorporated community resources, such as the YMCA’s Cancer Survivor Program, to meet programs, policies, and infrastructure goal. Finally, many programs incorporated the use of survivorship needs assessment to determine where resources are best allocated to ensure access to quality care and services.

Table 1.

Examples of survivorship activities in CDC’s National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program action plans

| Surveillance and applied research | Communication, education, and training | Programs, policies, and infrastructure | Access to quality care and services |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continue BRFSS cancer survivorship module and create a report based on results | Fact sheet on how to manage a cancer diagnosis | YMCA survivorship physical activity and nutrition project | Survivorship needs assessment report |

| Survey conducted of cancer patients and cancer center staff assessing barriers to receiving cancer treatment | Support group trainings on “people living through cancer” | Press release highlighting cancer survivorship data | Cancer survivorship resource guide to help patients, their families, and their loved ones find assistance and support |

| Survivorship aftercare plan utilization survey | Conference for cancer survivors, caregivers, and health professionals on: nutrition, spirituality, stress management, and participation in clinical trials | Survivorship committee sent welcome letters to 74 commission on cancer centers to inform them of the committee | Patient navigation toolkit for health professionals to provide individualized support, care coordination, and targeted services |

Discussion

The vast majority of NCCCP action plans implemented public health strategies to address cancer survivorship during the study period from 2010 to 2013. More than a third of programs implemented activities every year of the study period. Most programs used evidence-based strategies, as recommended by CDC and partners in the NAP, which provides recommendations to ensure effective cancer survivorship interventions, and helps to guide activities across public health agencies [4]. This study is the first evaluation of cancer survivorship activities included in NCCCP action plans. This analysis is especially timely given the recent release of the NCCCP priorities that include addressing the needs of survivors [10].

Prior to the release of the new NCCCP priorities in 2010, survivorship activities within the NCCCP were already expanding. A 2005 superficial review of NCCCP cancer plans found that many plans included specific objectives focusing on building infrastructure for providing services, outreach to identify survivors, and assessing quality of life needs among survivors [15]. CDC has also prioritized survivor needs in both its public health research and programmatic activities in recent years [7]. These include research projects that identify survivor health behaviors [7, 16, 17], receipt of appropriate care among survivors [18–20], and survivor psychosocial and supportive needs [21, 22]. Programmatic initiatives include the funding of several national organizations to provide culturally relevant and linguistically appropriate health education materials and health promotion opportunities to cancer survivors through a variety of dissemination activities [7].

Despite CDC’s investment and the NCCCP’s clear commitment to addressing cancer survivor needs, some areas remain for improvement. First, there is a slight decrease in the percentage of programs incorporating survivorship activities from 2010–2011 to 2012–2013. This decrease may be artifactual, as only the first 2 years of the current 5-year funding period was available for analysis, and programs may implement survivorship activities in greater numbers in subsequent years of the current funding period. The decrease may also reflect a shift towards achieving other NCCCP priorities. While we cannot comment on statistical significance of percentages at this time, NCCCP survivorship activities will continue to be monitored throughout the period to ensure there is no further decrease. Second, the implementation of more CDC-recommended cancer survivorship activities (found in NAP) can be improved. This is not necessarily a situation unique to the NCCCP, but exists in many organizations that prioritize survivorship interventions. For instance, while many programs exist to educate and assist survivors with their diagnosis, solid evidence for particular interventions are lacking in several cases [15], and it is unclear whether traditionally underserved populations that often have higher cancer incidence and death rates [23] are benefiting from these interventions. Recent results from a randomized controlled trial examining the American Cancer Society’s long-running “I Can Cope” (ICC) survivor resource and education program found that while low-income, minority cancer survivors appreciated the ICC sessions offered, their information needs were still consistent with those in the control group [24]. Also, survivorship care plans, which are written documents that often include a summary of cancer treatment and recommendations for surveillance, preventive care, wellness behaviors, and symptoms reported following treatment, are increasingly being recommended by cancer care quality improvement organizations in order to increase patient knowledge of their treatment and help them cope with physical and psychological stress [25]. However, a recent analysis in some American hospitals showed that the majority were not using survivor care plans, and when used, they were restricted to primarily breast and colorectal cancer survivors [25]. Additionally, the plans were rarely given to survivors themselves and their primary care providers [25]. Starting in 2015, the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer will require accredited programs to implement treatment summaries and survivorship care plans to help improve communication, quality, and coordination of care for cancer survivors [26]. Finally, many survivors report confusion when it comes to accessing health care. Cancer patient navigation (PN) is a process that provides individualized assistance to cancer patients, families, and caregivers to help overcome healthcare system barriers and facilitate timely access to quality health and psychosocial care from pre-diagnosis through all phases of the cancer experience [27]. Patient navigators (PNs) assist patients in overcoming barriers to cancer screening and treatment, offer peer counseling, provide linkages to financial and community resources, and provide culturally competent patient education, particularly among (but not limited to) the underserved [28–30]. PNs are increasingly being considered an important component to cancer care, and as such, the Commission on Cancer (CoC) is requiring CoC-accredited hospitals to include PN programs by 2015 [31]. While the use of PN may decrease the confusion that survivors face accessing health care, recognized standards and metrics for cancer survivor PN programs do not currently exist, which limits the ability for organizations such as the NCCCP to readily adopt PN programs. Specific and standard guidance for the implementation of PN programs, including training and certification needs for PNs, and measurements of effectiveness of PN programs would be beneficial to alleviate this issue.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. One strength is the use of an electronic reporting system to evaluate action plans from states, territories, and tribes affiliated with the NCCCP. Additionally, the action plan analysis utilized is an account of what was actually implemented and allowed us to look beyond the planning stages. While cancer plans convey the strategic direction of the program and coalition towards a public health issue (i.e., cancer survivorship), action plans provide currently implemented strategies, lessons learned, and other vital information to measure performance. Another strength is that the study examines whether objectives are in alignment with recommendations set forth in the NAP, an evidence-based source for addressing survivor needs. Limitations of the study include use of dichotomous indicators, which may not have provided a completely accurate picture of cancer survivorship in NCCCP plans. Another limitation inherent to these types of analyses is the wide range of interventions implemented at the program level. Some interventions are not mutually exclusive to recommended strategies, which may affect categorization of activities in this study. While we observe a decrease in proportion of programs that addressed cancer survivorship from 2010–2011 to 2012–2013, we do not have information to provide context for that finding. Also, all data is self-reported by programs and varies based on implementation methods utilized within each program. Finally, we present the current data from the first part of the current funding cycle (2012–2013): We are unable to assess specific program plans for survivorship activity in the near future.

Findings from this study will enhance monitoring of cancer survivorship activities by providing a baseline of interventions and recommendations currently implemented by programs. In addition, NCCCP conducts biennial surveys to evaluate all program activities, including those which support cancer survivors. The information gathered from these efforts will allow researchers to track progress and needs, as programs continue to support cancer survivors. Our study demonstrates that the vast majority of programs affiliated with the NCCCP have implemented survivorship activities in the last few years. This demonstrated commitment is necessary due to the expanding population of cancer survivors. Future directions for survivorship activities in the NCCCP include increasing the use of culturally appropriate and effective education resources, survivorship care plans, and patient navigation to increase the quality and duration of life among all cancer survivors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Cancer Prevention and Control.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Conflict of interest All authors have read and approved the manuscript, and there are no financial disclosures and conflicts of interests.

Contributor Information

J. Michael Underwood, Email: jmunderwood@cdc.gov, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, N.E., MS-F76, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA.

Naheed Lakhani, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, N.E., MS-F76, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA.

Elizabeth Rohan, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, N.E., MS-F76, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA.

Angela Moore, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, N.E., MS-F76, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA.

Sherri L. Stewart, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 4770 Buford Highway, N.E., MS-F76, Atlanta, GA 30333, USA

References

- 1.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. Committee on cancer survivorship: Improving care and quality of life. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2006. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Underwood JM, et al. Surveillance of demographic characteristics and health behaviors among adult cancer survivors—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2009. 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Moor JS, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2013;22(4):561–70. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A national action plan for cancer survivorship: advancing public health strategies. Atlanta (GA): US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabatino SA, et al. Receipt of cancer treatment summaries and follow-up instructions among adult cancer survivors: results from a national survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):32–43. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0242-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dulko D, et al. Oncology Nursing Forum. Onc Nurs Society; 2013. Barriers and facilitators to implementing cancer survivorship care plans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairley TL, et al. Addressing cancer survivorship through public health: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Women’s Health. 2009;18(10):1525–31. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. Centers for disease control and prevention; [Accessed February 25, 2014]. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/about.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Major A, Stewart SL. Celebrating 10 years of the national comprehensive cancer control program, 1998 to 2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(4):A133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart SL, et al. Gynecologic cancer prevention and control in the National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program: progress, current activities, and future directions. J Women’s Health. 2013;22(8):651–7. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neri A, Stewart SL, Angell W. Peer reviewed: radon control activities for lung cancer prevention in National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program plans, 2005–2011. Preventing chronic disease. 2013:10. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunne K, et al. Peer reviewed: an update on tobacco control initiatives in comprehensive cancer control plans. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2013:10. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White D. Evidence-based interventions and screening recommendations for colorectal cancer in comprehensive cancer control plans: a content analysis. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Momin B, Richardson L. An analysis of content in comprehensive cancer control plans that address chronic hepatitis B and C virus infections as major risk factors for liver cancer. J Community Health. 2012;37(4):912–6. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9507-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollack LA, et al. Cancer survivorship: a new challenge in comprehensive cancer control. Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16 (Suppl 1):51–9. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0452-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Underwood JM, et al. Persistent cigarette smoking and other tobacco use after a tobacco-related cancer diagnosis. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):333–44. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0230-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajotte EJ, et al. Community-based exercise program effectiveness and safety for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(2):219–28. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0213-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huntsman DG, Gilks CB. Surgical staging of early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(2):460–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Malley CD, et al. The implications of age and comorbidity on survival following epithelial ovarian cancer: summary and results from a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study. J Women’s Health. 2012;21(9):887–94. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton AS, et al. Regional, provider, and economic factors associated with the choice of active surveillance in the treatment of men with localized prostate cancer. JNCI Monographs. 2012;2012(45):213–20. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trivers KF, et al. Issues of ovarian cancer survivors in the USA: a literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2889–98. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1893-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roland KB, et al. A literature review of the social and psychological needs of ovarian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2013;22(11):2408–18. doi: 10.1002/pon.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2007 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin MY, et al. Meeting the information needs of lower income cancer survivors: results of a randomized control trial evaluating the American Cancer Society’s “I Can Cope”. Journal of health communication. 2014:1–19. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.821557. ahead-of-print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birken SA, et al. Following through: the consistency of survivorship care plan use in United States cancer programs. Journal of Cancer Education. 2014:p1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0628-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stricker CT, O’Brien M. Implementing the commission on cancer standards for survivorship care plans. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:15–22. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.S1.15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL. History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer. 2011;117(S15):3537–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients. Cancer. 2005;104(4):848–55. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Percac-Lima S, et al. A culturally tailored navigator program for colorectal cancer screening in a community health center: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):211–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0864-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells KJ, et al. Do community health worker interventions improve rates of screening mammography in the United States? A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(8):1580–98. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cancer, A.C.o.S.C.o. Cancer program standards 2012: ensuring patient-centered care. American College of Surgeons; 2011. [Google Scholar]