Abstract

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a receptor tyrosine kinase critical in tumor growth and a major target for anti-cancer drug development. However, so far there is no effective system to monitor its activities in vivo. Here we report a novel approach to monitor EGFR activation based on the bi-fragment luciferase reconstitution system. The EGFR receptor and its interacting partner proteins (EGFR, Grb2, and Shc) were fused to N-terminal and C-terminal fragments of the firefly luciferase. After establishing tumor xenograft from cells transduced with the reporter genes, we show that the activation of EGFR and its downstream factors could be quantified though optical imaging of reconstituted luciferase. Changes in EGFR activation could be visualized following radiotherapy or EGFR inhibitor treatment. Rapid and sustained radiation-induced EGFR activation and inhibitor-mediated signal suppression were observed in the same xenograft tumors over a period of weeks. Our data therefore suggests a new methodology where activities of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) can be imaged and quantified optically in mice. This approach should be generally applicable to study biological regulation of RTKs as well as to develop and evaluate novel RTK-targeted therapeutics.

Introduction

The use of bioluminescent firefly luciferase to genetically label cells and proteins has greatly advanced biomedical research. For example, by use of commercially available optical imaging devices, it is now possible to image a few hundred to a few thousand luciferase-expressing tumor cells anywhere in mice (1–3). This capability has made it possible to track the fate of small numbers of tumor cells over the course of days, weeks, or even months, greatly facilitating the studies of tumor development and tumor metastases. As this can be accomplished in the same animals over the course of the experiments, the savings in animal costs and increases in experimental reproducibility are considerable. In addition, biological insights that were otherwise unavailable were often gained from non-invasive imaging studies. For these reasons, there is a surge in interest in developing novel luciferase-based assays that can image ever more sophisticated biological processes, especially in vivo in live animals (4–6).

In this study, we attempt to image the activities of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor by use of the bioluminescent imaging approach. The EGF family of proteins is one of the most important in regulating mammalian cellular growth and proliferation(7). They also play crucial roles in tumor development and tumor response to therapy (8–10). However so far there is no effective system where the in vivo activation of EGFR can be monitored effectively. This is because EGFR activation leads to complicated cascades of molecular events with no specific transcriptional activation of any downstream genes that are amenable for constructing the commonly used promoter-based luciferase reporter systems. However, it is now recognized that ligand binding to EGFR leads the dimerization of the EGFR and activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) activities of EGFR(10). This in turn leads to the activation and association with of downstream factors such as the Shc and Grb2.

We reasoned that the use of the bi-fragment luciferase re-constitution system(4, 11–16), which was shown to be able to image interacting protein pairs in tissue culture and in live animals(11, 14, 17), will allow us to assess EGFR activities through monitoring the re-constitution of the luciferase activities brought about by the interaction of activated EGFR with its downstream protein partners. Our results show this approach provides a powerful tool to study the biological regulation of EGFR activity in vivo as well as to develop/evaluate novel therapeutics targeting the EGFR pathway.

Materials and Methods

Construction of the reporter plasmids

Full-length genes (EGFR, Grb2, and Shc) required to construct the reporters were obtained through different channels. The full length sequences coding for human EGF receptor (Gene Bank accession# X00588) and the adaptor protein Grb2 (accession# BC000631) were cloned through RT-PCR from cDNA derived from HCT116 cells, respectively. In using PCR to amplify these genes, the stop codons were removed while the native Kozak sequences were preserved. PCR was also used to amplify the human p52Shc (accession# BC014158) cDNA from a plasmid generously provided by Dr. Alexander Sorkin (Departments of Pharmacology, University of Colorado Health Science Center, Aurora, CO). In all three cases, restriction enzyme sites were engineered into the primer to facilitate subsequent fusion with the luciferase moieties. Before cloning into the expression vectors pLNCX/pLPCX, the PCR-amplified genes were verified through sequencing. The N-terminal (NLuc, aa2-416) and C-terminal (CLuc, aa398-550) halves of the luciferase gene were generated by PCR from pGL3 (Promega,) by use of 5′ primers containing the (Gly4/Ser)3 flexible linker and restriction enzyme sites EcoRI, MluI, XhoI and 3′ primers with stop codon and restriction enzyme sites EcoRI and XhoI (supplementary Figure S1). The fusion genes EGFR-NLuc and Grb2-Nluc were then created (through restriction enzyme digestions and ligations, please see Supplementary Data section for more details on the cloning strategy) and subcloned into retrovirus vector pLPCX (Clontech) in proper order while fused EGFR-CLuc and Shc-Cluc genes were ligated into retrovirus vector pLNCX (Clontech) downstream of the CMV promoter. pLPCX contains the puromycin resistance gene and pLNCX confers resistance to G418 for selection of stable integration of the transgenes in target cells. The primers used for cloning the plasmids are provided in the Supplementary Data section.

Transduction of the reporter into tumor cells

Stable transfectants of the non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma cell line H322 (kindly provided by Barbara A. Helfrich of Dept of Medicine, UCHSC, Aurora, CO) were established by serial infections of retroviruses containing the reporter genes. Three transduced cell lines were derived as a result. These include cell lines that contain the binary reporters EGFR/EGFR-luc (EGFR-Nluc+EGFR-CLuc), EGFR/Shc-luc(EGFR-Nluc+Shc-Cluc) and Grb2/Shc-luc(Grb2-Nluc+Shc-Cluc). More details on establishing reporter-transduced cells are provided in the Supplementary Data section.

Imaging of the reporter in vitro

Stably transfected EGFR/Shc-Cluc and Grb2/Shc-Cluc cells (5 ×104 cells per well in 250μl of complete growth RPMI1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS) were seeded into 48-well plates. When they grew to 80% confluence, growth media were replaced with media containing no serum to starve the cells for 14–16 hours. Subsequently, cells were treated with EGF (Cell Signal Technology, Beverly, MA) at 20ng/ml EGF in RPMI1640 medium at 37°C for 15min. After incubation with EGF, the media were replaced to luciferin-containing media (125μl of 150 μg/ml lucifercin in DMEM medium without sodium pyruvate, luciferin was obtained commercially from Xenogen, Alameda, CA). Photon output for each well was measured 10 min after addition of luciferin with the Xenogen IVIS200 optical imaging system.

For EGFR inhibitor (Gefitinib or Erbitux) assays, cells were treated with inhibitor after 14–16hr serum starvation and before EGF induction. For Gefitinib treatment, cells were treated at 37°C for 8 hours. For Erbitux treatment, cells exposed at 37°C for 15min. EGF was then added to the cells at 20 ng/ml for 15 minutes. Subsequently, lucifercin was added and photon output for each well was measured 10 min later in IVIS200.

Western blot analysis

Standard protocols for western blot analysis were followed. Detailed protocols as well as antibody information are provided in the Supplementary Data section.

Imaging the reporter in vivo

To image EGFR activity in tumors, H322 cells transduced with the reporters were subcutaneous injected into 4–6 weeks old female athymic nude mice, which were obtained from NCI (Bethesda, MD) and maintained in accordance with University of Colorado Health Sciences Center institutional IACUC guidelines. About 5×106 reporter-bearing H322 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) into mice in 50μl of matrigel dissolved in PBS solution in the legs. When tumors reached 5–6 mm in diameter, mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups.

In some groups, animals were treated with X-rays (1x or 3x 6Gy radiation). In addition, the drug gefitinib was administered to some groups at 50mg/kg i.p daily for 10 days. In cases of combined X-ray and gefitinib group, the drug was administered 1 day before irradiation. Luciferase activities in the mice were then imaged at various time points 10 min after i.p. injection of 200 μl of 15 mg/ml luciferin in H2O.

Statistical Method

Student’s t test was used where necessary. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Design of a bi-fragment luciferase reconstitution system for non-invasive observation of EGFR activation

We set out to develop a novel system to examine EGFR activation in vivo non-invasively. To achieve this goal, a bi-fragment luciferase reconstitution scheme was used. We took advantage of the fact that EGFR activation necessitates 1) dimerization of EGFR on the surface of cells; 2) activation of the kinase activities of EGFR and the subsequent phosphorylation of its downstream partners such as Shc. This leads to the physical association of EGFR and Shc, and the adaptor protein Grb2.

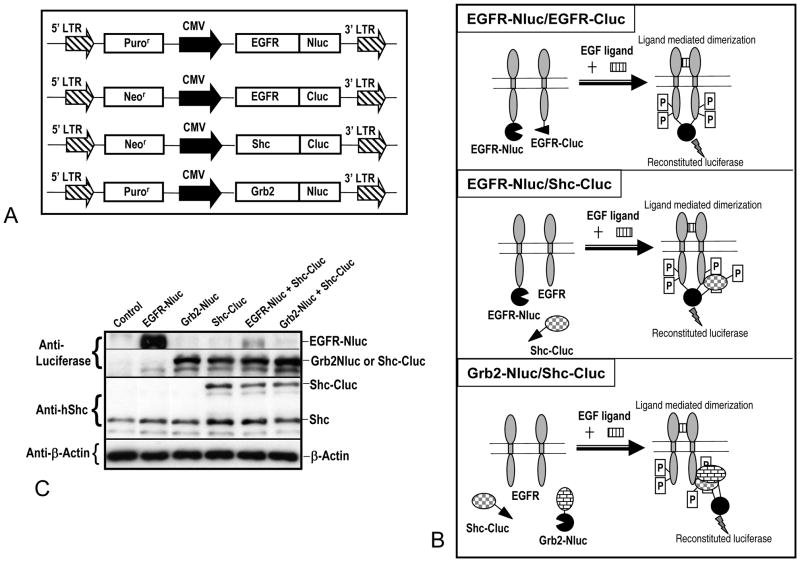

We designed a system where EGFR and its interaction partners Shc and Grb2 were fused to either N-terminal or C-terminal fragments of the firefly luciferase (Figure 1A). We reasoned that in cells stably transduced with these reporters, activation of the EGFR would lead to the physical interaction of EGFR with its partner proteins (EGFR itself, Shc, or Grb2), which could potentially reconstitute the active luciferase enzyme that could be imaged optically (Figure 1B). A set of chimeric genes with EGFR, Grb2, Shc fused with either N- or C- terminal luciferase fragments were (Figure 1A) transduced into a human non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma (NSCLC) line H322. The expressions of the recombinant proteins were then examined through western blotting and clear evidence for the presence of both endogenous and recombinant proteins were observed (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Structure of a bi-fragment luciferase reconstitution system for detecting EGFR pathway activation.

A) Structures of various fusion reporter proteins between EGFR pathway proteins (EGFR, Shc, Grb2) and the fragments of firefly luciferase (Nluc, Cluc represents the N- and C- terminal halves of the firefly luciferase gene). The retroviral vector pLPCX and pLNCX were used to carry the reporter genes (with resistance genes for puromycin and neomycin, respectively).

B) Graphic illustration of the principles of EGFR activity reporters used in this study. Three different versions of the reporters were shown.

C) Western blot analyses of the expression of endogenous and recombinant EGFR pathway proteins after transduction of one or both components of the reporter system into the human lung cancer line H322.

Validation of EGF-induced reporter gene activation in tissue culture

We next measured luciferase activities in H322 cells stably transduced with pairs of recombinant reporter genes in the presence or absence of EGF. After initial screening, we found that EGF addition induced no increase in luciferase signals in cells transduced with EGFR/EGFR-luc fragments (data not shown), indicating no reconstitution under these circumstances, which perhaps reflected the unfavorable spatial conditions for the luciferase moieties to reconstitute when the EGFR receptors dimerize. On the other hand, cells transduced with EGFR/Shc-luc fragments or Grb2/Shc-luc fragments showed robust EGF-mediated induction of luciferase signals, indicating reconstitution of the enzyme accompanied by EGFR activation (Figure 2A&B). The functional relevance of the reporter system was then examined through optical imaging and western blotting. It is clear that EGF induced activation of both EGFR/Shc-luc and Grb2/Shc-luc reporters were correlated with phosphorylation/activation of the endogenous or recombinant EGFR and Shc in cells (Figure 2C).

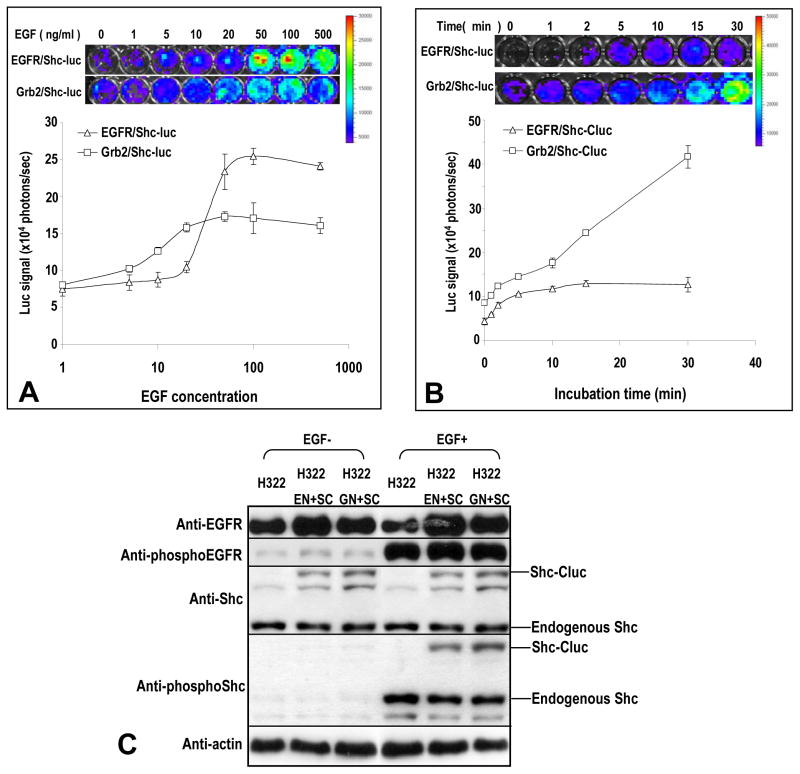

Figure 2. In vitro characterization of the kinetics of EGF-induced activation of the bi-fragment luciferase reporter.

A) The dose response curve for the EGFR/Shc-luc reporter and the Grb2/Shc-luc reporter. The top panel shows representative images of reporter-transduced cells (in 48-well plates) treated with different concentrations of EGF at 37°C 15 minutes and then imaged in the IVIS200 instrument while the lower panel shows the quantitative dose response of the reporter activation after EGF addition. The error bars represent standard deviations derived from 3–5 data points.

B) The time course of reporter activation for the same EGFR reporters. The top panel shows representative images of reporter-transduced cells treated with 20 ng/ml of EGF for various lengths of time and imaged in the IVIS200 instrument for reconstituted luciferase gene activities. The lower panel shows the time course of reporter activation. The error bars represent standard deviations derived from 3–5 data points.

C) Western blot analyses of EGF-mediated activation of endogenous and recombinant EGFR and downstream factors. Cell transduced with various recombinant reporter genes were incubated with EGF (20 ng/ml for 15 minutes) and than lysed. Antibodies against total and phosphorylated EGFR and Shc proteins were used to analyze total as well activated forms of these proteins in western blots. EN+SC represents EGFR-Nluc+Shc-Cluc while GN+SC represents Grb2-Nluc+Shc-Cluc. The phosphorylations of the proteins correlated well with optical imaging of the reporter cells (shown in A & B).

A careful examination showed that the two reporter combinations showed different kinetics after EGF treatment. In dose response studies, after 15 minutes’ incubation, the EGFR/Shc-luc reporter showed a slower dose response at lower EGF concentrations but also reached a higher plateau. In contrast, the Grb2/Shc-luc reporter showed relatively faster EGF dose response but reached a lower plateau (Figure 2A). In time course studies, EGFR/Shc-luc showed earlier induction but reached a lower plateau (at 2.5 fold over control) 15 minutes after EGF addition(Figure 2B), while Grb2/Shc-luc had slower induction but continued to rise (above 5 fold induction over control) 30 minutes after EGF addition. In addition, western blot analyses indicate that the activation of reporter genes correlated well with phosphorylation of endogenous and recombinant EGFR and Shc proteins (Figure 2C).

An important point to note is the impressive ability the new reporter system to detect the different kinetics of EGF-mediated induction between EGFR/Shc and Grb2/Shc. This has not been possible in the past with western blot-based approaches. It clearly demonstrates the power of our molecular imaging approach for EGFR activity.

Evaluating the efficacy of known EGFR inhibitors in vitro

The utility of the reporter system was further evaluated in testing the efficacy of known EGFR inhibitors in tissue culture cells. Gefitinib has been shown to be a potent and specific small molecule inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase activities of EGFR(18). As shown in Figure 3A, significant (p<0.05, Student’s t test) inhibition of EGF-induced activation of both EGFR/Shc-luc and Grb2/EGFR-luc reporters was observed in H322 cells beginning at gefitinib concentration 0.25 μM. Another EGFR inhibitor, the monoclonal antibody erbitux(19), also exhibited potency in inhibiting the activation of the reporters, significantly down-regulating the reporter activities at concentrations of 1 nM or more. Western blot analysis of cell lysates indicated that the activities of the reporters correlated well with the phosphorylation status of the EGFR, Shc proteins as well as the presence of the inhibitors (Figure 3C).

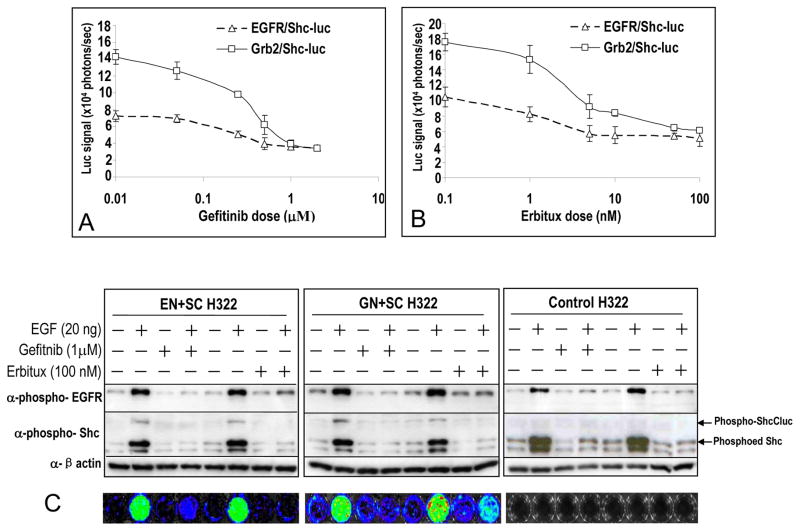

Figure 3. Quantitative imaging of the effect of EGFR inhibitors on the EGFR reporter activities.

A) Effective suppression of both EGFR/Shc-luc and Grb2/Shc-luc reporters by the small molecule EGFR kinase inhibitor gefitinib. Cell transduced with the reporters were incubated with EGF (at 20 ng/ml) and various concentrations of the inhibitors. After 15 minutes of incubation, the cells were imaged for luciferase activities. The error bars represent standard deviations of 3–5 triplicate data points.

B) Effective suppression of the both EGFR/Shc-luc and Grb2/Shc-luc reporters by the monoclonal antibody EGFR inhibitor Erbitux (cetuximab). The error bars represent standard deviations of 3–5 triplicate data points.

C) Western blot analyses of the effect of EGFR inhibitors (gefinib or erbitux) on EGF-induced activation of EGFR and its downstream protein Shc. The phosporylation status of the proteins, which indicated the activation status, was closely correlated with the addition of the inhibitors and the reconstitution of luciferase activities (A&B).

Validation of the EGFR activity reporters in xenogfraft tumors undergoing radiotherapy

Our data in vitro suggest that the bi-fragment reconstitution system is capable of quantifying EGFR activation. The real test of the utility of the bi-fragment reconstitution system, however, is whether it is able report the in vivo activities of EGFR.

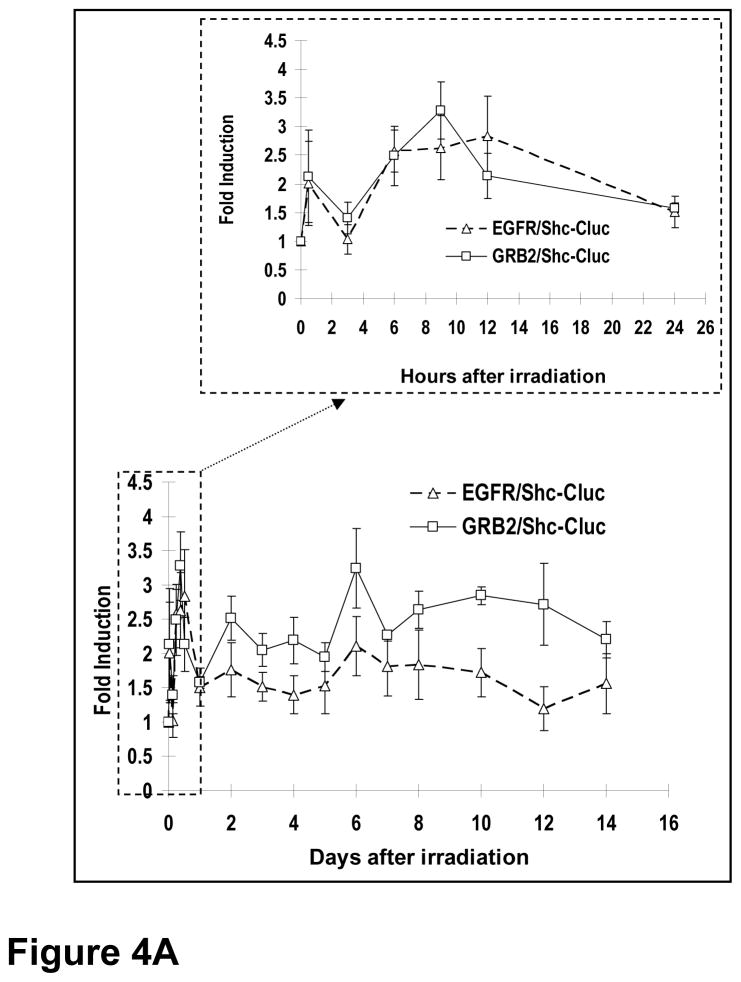

In order to assess the properties of the EGFR reporter systems in vivo, we established xenograft tumors of H322 lung cancer line with the EGFR/Shc-luc reporter and the Grb2/Shc-luc reporter, respectively. When these tumors reached 5–7 mm in diameters, they were irradiated and the EGFR activities were followed in the irradiated tumors. Our results showed that ionizing radiation induced a very rapid activation of EGFR activities (~2 fold above background) within 1 hour of irradiation in the tumors (Figure 4A). This was true of both reporter systems. The reporter activities rapidly dropped to background levels and then quickly climbed even higher levels (~3 fold above background) at 3 hrs after irradiation. For EGFR/Shc-luc, after the initial surge in the first day (p<0.02 at 30 minutes, 3, 6, 9, and 12 hrs), the level dropped to lower but still significantly above control levels at day 2 (p<0.05). Interestingly, another peak was observed at day 6(p<0.04), following which persistently higher EGFR activity levels were seen until day 10. This pattern of “twin-peak” activation was also observed for the Grb2/Shc-luc reporter, which showed even higher levels of induction (p<0.05 for all time points in day 1, except at 3hrs, and days 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 & 10). These results were generally consistent with published reports indicating that radiation induced activation of the EGFR pathway (20, 21). However, the kinetics of activation is different from the earlier studies due to the fact that different irradiation and observation schedules were used in the earlier studies.

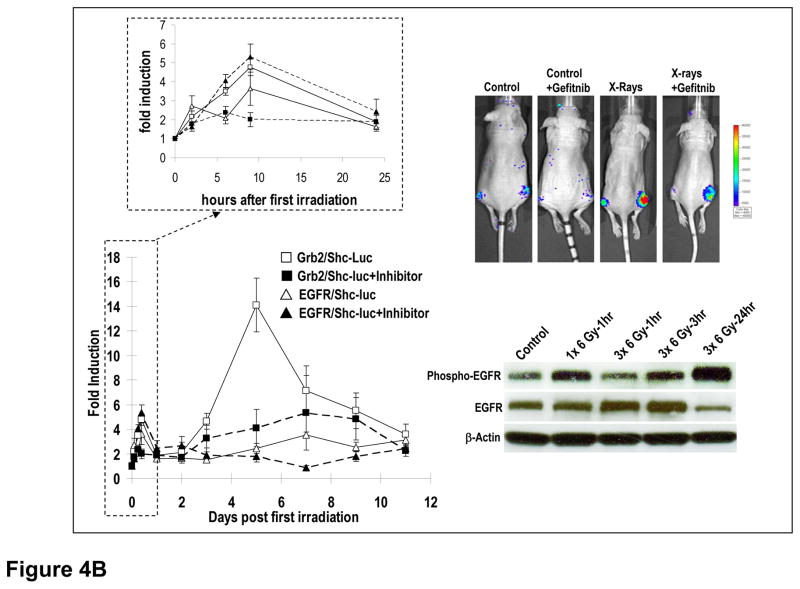

Figure 4. In vivo imaging of EGFR activation during radiotherapy.

A) Radiotherapy induced activation of EGFR/Shc-luc (broken lines) and Grb2/Shc-luc (solid lines) reporters in H322 xenograft tumors. After reporter-transduced H322 lung tumor cell (5×106) implantation (subcutaneous) and tumor formation (with diameters around 5–7 mm), the tumors were irradiated with X-rays (6 Gy). The activities of the EGFR were then imaged. Shown were data obtained during the two weeks after radiotherapy. Data of the first 24 hours after radiotherapy were plotted in a separate graph (top panel) to show more details of activation during this period. The error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM, n=4).

B) The effect of the small molecule EGFR inhibitor gefitinib on radiotherapy-induced activation of the EGFR receptors. When reporter-transduced H322 tumors were 5–7 mm in diameter, the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib were administered on a daily basis for 10 days. Radiation (3×6 Gy) was then administered every other day starting one day after drug administration (days 0, 2, 4 on the top panel). Quantitative imaging of EGFR activation was carried out and the data plotted (Left panels). Top left panel shows data from the 1st 24 hours in more details. The error bars represent SEM (n=3–5). Top right panel shows representative images of mice with the reporter-transduced tumors after various treatments. Lower right panel shows a western blot autoradiograph of total EGFR, activated (phosphor-EGFR), and β-actin levels in tumors obtained (from sacrificed mice) from at different times points after they were irradiated in vivo.

In order to simulate multi-fraction radiotherapy in the clinic, additional experiments were carried out where the tumors were given 3 doses of radiation (Figure 4B, left panels). Similar to the single dose radiation, the multi-fraction radiation induced significant increases in EGFR activities. For EGFR/Shc-Luc, the induction is significantly different form controls at all time points observed (p<0.03 compared to control levels). For Grb2/Shc-luc, multi-fraction radiation caused even more pronounced increases (.e.g. up to 14 fold increase on day 5, p<0.03 compared to control levels). The increase in EGFR activation induced by additional exposures to radiation were also confirmed by western blot analysis of EGFR phosphorylation in irradiated tumors (Figure 4B, lower right panel) and cells (Supplementary Figure S3). One interesting aspect of the in vivo western data is the changes in total EGFR levels, which are not completely concordant with phosphorylated EGFR levels. Total EGFR levels showed an increase at 1 hrs and 3 hrs after the 3rd fraction of radiation but a decrease 24 hrs after the 3rd fraction despite a very significant increase in phosphorylated EGFR levels (Figure 4B, lower right panel). This is in contrast to the tissue cultured cells, did not show any total EGFR fluctuations after multiple radiation exposures despite an increase in phosphorylated EGFR (Figure S3, Supplementary Data).

In addition, the differences between the EGFR/Shc-luc and Grb2/Shc-luc reporters were also amplified with the multi-fraction radiations, particularly at later time points. The exact mechanisms underlying the differences between the two reporters are not known. However, they probably reflected the fact that the activity of EGFR/Shc-Luc reporter is linear with interaction between EGF and the EGFR-luc containing EGFR dimers while the activity of the Grb2/Shc-luc reporter is the catalytic results of activated endogenous and exogenous EGFR. They clearly indicated the more sensitive nature of our reporter system when compared with traditional western blot or ELISA-based approach for detecting EGFR activities.

Our results also indicated that gefitinib could inhibit Grb2/Shc-luc reporter activation in vivo very effectively both at earlier times (right after the first radiation dose) and at later times during therapy (e.g. p<0.04 on day 5, the day the induced Grb2/Shc-luc peaked, Figure 4B). In contrast, the EGFR/Shc-luc reporter was not inhibited effectively right after the first radiation therapy dose. However, its second peak of activation (day 7) was inhibited significantly (p<0.02). Currently we do not have a plausible explanation for the lack of EGFR/Shc-luc activities in the first 24 hrs.

In summary, both in vitro and in vivo results support the feasibility of our new luciferase based reporter system for non-invasive imaging of EGFR activities.

Discussion

The ability to “see” a biological process in action is always sought after in biomedical research. The advent of sensitive optical imaging system makes it possible to visualize and quantify luminescence and fluorescence in vivo in rodents. This capability, in combination with the availability of natural or artificially “improved” fluorescent proteins (i.e. EGFP) or luminescent proteins (e.g. fire fly luciferase) greatly expanded the horizons of molecular imaging in small animals by making it possible to genetically engineer various reporter systems. Our results with artificially engineered EGFR activity reporters provide an important example of the power of the luciferase-based optical imaging reporter in studying sophisticated signal transduction pathways and drug action.

Labeling of individual cell types/proteins to study their trafficking/distribution in vivo or the evaluation of in vivo promoter activities have been the most common usage for luciferase molecular imaging. While many of these studies have greatly advanced our understanding of in vivo biology of the cells/proteins of interest with regard to their regulation at the transcriptional, translational, or post-translational levels, the approach is limited to cases where the study subjects are whole cells, gene promoters, or proteins with physiological variations in post-translational stabilities. For many biological processes, especially ones involving enzymatic activities, the imaging approaches are not well developed. One example where luciferase imaging was used to study in vivo enzymatic activity was the successful engineering of a luciferase-based caspase activity reporter(22, 23). In another example a modified luciferin substrate was used to detect caspase activities(24).

Our study deals with the activity of the EGF receptor activities. EGFR is an archetypical member of the receptor tyrosine kinase family. Numerous members of the RTK family play crucial roles in various biological processes. The interest in EGFR and related receptors (i.e. Her2/neu) is especially strong because the roles they play in tumor biology and in anti-cancer drug development(10, 25). To date, there are some reports of attempts to image EGFR. Some deal only with the distribution of the receptor protein rather than its biological activities(26). This type of studies usually involve the use of labeled antibodies or ligands that are specific for EGFR(27, 28). EGFR extracellular domain dimerization has been imaged in at the cellular level through reconstitution of the lacZ enzyme(29, 30). However, this strategy does not address the kinase activity of the EGFR protein and is not suitable for imaging in live animals. There are also reports that used the FRET strategies and fluorescent protein pairs to detect EGFR activation(31–34). Again this strategy is not suitable for small animal imaging.

Our study uses the bi-fragment luciferase re-constitution assay to image kinase activity of EGFR through quantification of the interaction between activated EGFR and its downstream partners. It is a novel system that has not previously been reported. The success of this strategy demonstrates a powerful approach for studying the in vivo regulation of the EGFR receptors. In addition, it is generally applicable for studying other member of the RTK family because many of these use similar kinase cascades. Examples of these include the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), the insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGFR), and TGF-β receptor (TGFβR), etc. The availability of a non-invasive and quantitative imaging system should greatly facilitate the study of the biology of these RTKs under normal (i.e. physiological, developmental) and pathological (i.e. cancer) conditions. It should also facilitate the development and evaluation of novel therapeutics based on these RTKs.

Finally, our data derived from monitoring EGFR reporter activities during radiotherapy illustrated how the optical imaging reporters could be used to monitor in vivo signal transduction pathways in the course of therapy. For example, the observation of radiation-induced “twin-peak” pattern of activation over the course of a week in the same tumors could only be achieved with a non-invasive imaging system. Such radiation-induced EGFR activation may provide an explanation as to why combined administration of EGFR inhibitors with radiotherapy has potent anti-tumor efficacy in a number of malignancies in human patients (9, 35).

In summary, we have developed a novel bi-fragment luciferase reconstitution-based molecular imaging system to study EGFR. Our method should set a precedent for studying other RTKs by use of the molecular imaging approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Helfrich of Dept of Medicine, Univ. of Colorado Health Sciences Center for providing the H322 cell line. We also want to thank Dr. Alexander Sorkin of Dept. of Pharmacology, University of Colorado Health Sciences Center for providing the Shc52-encoding plasmid. This study was supported in part by grant EB001882 from US National Institute of Bioimaging and Bioengineering, grant CA81512 from the US National Cancer Institute, a grant from the Komen Foundation for Breast Cancer Research to C-Y. Li. This study is also supported by a National Basic Research Project of China (2004CB518804 to Q. Huang), National Science Foundation of China (NSFC) for Outstanding Young Investigators (30325043 to Q. Huang, and 30428015 to C-Y. Li).

References

- 1.Sweeney TJ, Mailander V, Tucker AA, et al. Visualizing the kinetics of tumor-cell clearance in living animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(21):12044–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cao YA, Wagers AJ, Beilhack A, et al. Shifting foci of hematopoiesis during reconstitution from single stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(1):221–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2637010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Negrin RS, Contag CH. In vivo imaging using bioluminescence: a tool for probing graft-versus-host disease. Nature reviews. 2006;6(6):484–90. doi: 10.1038/nri1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villalobos V, Naik S, Piwnica-Worms D. Current state of imaging protein-protein interactions in vivo with genetically encoded reporters. Annual review of biomedical engineering. 2007;9:321–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.152044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross S, Piwnica-Worms D. Spying on cancer: molecular imaging in vivo with genetically encoded reporters. Cancer cell. 2005;7(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillies RJ. In vivo molecular imaging. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2002;39:231–8. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Citri A, Yarden Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(7):505–16. doi: 10.1038/nrm1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacouture ME. Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(10):803–12. doi: 10.1038/nrc1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nyati MK, Morgan MA, Feng FY, Lawrence TS. Integration of EGFR inhibitors with radiochemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(11):876–85. doi: 10.1038/nrc1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(5):341–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulmurugan R, Umezawa Y, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive imaging of protein-protein interactions in living subjects by using reporter protein complementation and reconstitution strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(24):15608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242594299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massoud TF, Paulmurugan R, De A, Ray P, Gambhir SS. Reporter gene imaging of protein-protein interactions in living subjects. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2007;18(1):31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SB, Ozawa T, Watanabe S, Umezawa Y. High-throughput sensing and noninvasive imaging of protein nuclear transport by using reconstitution of split Renilla luciferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(32):11542–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401722101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luker KE, Smith MC, Luker GD, Gammon ST, Piwnica-Worms H, Piwnica-Worms D. Kinetics of regulated protein-protein interactions revealed with firefly luciferase complementation imaging in cells and living animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(33):12288–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massoud TF, Paulmurugan R, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of homodimeric protein-protein interactions in living subjects. Faseb J. 2004;18(10):1105–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1128fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray P, Pimenta H, Paulmurugan R, et al. Noninvasive quantitative imaging of protein-protein interactions in living subjects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(5):3105–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052710999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulmurugan R, Massoud TF, Huang J, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging of drug-modulated protein-protein interactions in living subjects. Cancer research. 2004;64(6):2113–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herbst RS, Fukuoka M, Baselga J. Gefitinib--a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(12):956–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg RM. Cetuximab. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;(Suppl):S10–1. doi: 10.1038/nrd1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt-Ullrich RK, Mikkelsen RB, Dent P, et al. Radiation-induced proliferation of the human A431 squamous carcinoma cells is dependent on EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation. Oncogene. 1997;15(10):1191–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagan M, Yacoub A, Dent P. Ionizing radiation causes a dose-dependent release of transforming growth factor alpha in vitro from irradiated xenografts and during palliative treatment of hormone-refractory prostate carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(17):5724–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laxman B, Hall DE, Bhojani MS, et al. Noninvasive real-time imaging of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):16551–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252644499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KC, Hamstra DA, Bhojani MS, Khan AP, Ross BD, Rehemtulla A. Noninvasive molecular imaging sheds light on the synergy between 5-fluorouracil and TRAIL/Apo2L for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(6):1839–46. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu JJ, Wang W, Dicker DT, El-Deiry WS. Bioluminescent imaging of TRAIL-induced apoptosis through detection of caspase activation following cleavage of DEVD-aminoluciferin. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4(8):885–92. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.8.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cells assemble and align gold nanorods conjugated to antibodies to produce highly enhanced, sharp, and polarized surface Raman spectra: a potential cancer diagnostic marker. Nano letters. 2007;7(6):1591–7. doi: 10.1021/nl070472c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arwert E, Hingtgen S, Figueiredo JL, et al. Visualizing the dynamics of EGFR activity and antiglioma therapies in vivo. Cancer research. 2007;67(15):7335–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Remy S, Reilly RM, Sheldon K, Gariepy J. A new radioligand for the epidermal growth factor receptor: 111In labeled human epidermal growth factor derivatized with a bifunctional metal-chelating peptide. Bioconjugate chemistry. 1995;6(6):683–90. doi: 10.1021/bc00036a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sako Y, Minoghchi S, Yanagida T. Single-molecule imaging of EGFR signalling on the surface of living cells. Nature cell biology. 2000;2(3):168–72. doi: 10.1038/35004044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blakely BT, Rossi FM, Tillotson B, Palmer M, Estelles A, Blau HM. Epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization monitored in live cells. Nature biotechnology. 2000;18(2):218–22. doi: 10.1038/72686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wehrman TS, Raab WJ, Casipit CL, Doyonnas R, Pomerantz JH, Blau HM. A system for quantifying dynamic protein interactions defines a role for Herceptin in modulating ErbB2 interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(50):19063–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605218103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verveer PJ, Wouters FS, Reynolds AR, Bastiaens PI. Quantitative imaging of lateral ErbB1 receptor signal propagation in the plasma membrane. Science (New York, NY. 2000;290(5496):1567–70. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5496.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ting AY, Kain KH, Klemke RL, Tsien RY. Genetically encoded fluorescent reporters of protein tyrosine kinase activities in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(26):15003–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211564598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorkin A, McClure M, Huang F, Carter R. Interaction of EGF receptor and grb2 in living cells visualized by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy. Curr Biol. 2000;10(21):1395–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang X, Sorkin A. Coordinated traffic of Grb2 and Ras during epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis visualized in living cells. Molecular biology of the cell. 2002;13(5):1522–35. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-11-0552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;354(6):567–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.