This study raises important questions regarding optimal communication with patients about costs. Survey data show that patients, regardless of financial distress, do not want their treatments selected based upon cost considerations. Better patient educational tools are needed to help increase cost awareness and awareness of value. To master this mode of discourse and to help ease patients’ financial toxicity, oncologists will need to master a new set of data and develop new skills. This new knowledge and proficiency are as vital to good oncology care as all other clinical acumen.

Keywords: Cost of illness, Attitudes, Choice behavior, Neoplasms

Abstract

Background and Purpose.

The cost of illness in cancer care and the subsequent distress has attracted scrutiny. Guidelines recommend enhanced discussion of costs, assuming this will reduce both stress and costs. Little is known about patient attitudes about cost considerations influencing treatment decisions.

Methods.

A convenience-sample survey of patients currently receiving radiation and/or intravenous chemotherapy at an outpatient cancer center was performed. Assessments included prevalence and extent of financial burden, level of financial distress, attitudes about using costs to influence treatment decisions, and frequency or desirability of cost discussions with oncologists.

Results.

A total of 132 participants (94%) responded. Overall, 47% reported high financial stress, 30.8% felt well informed about costs prior to treatment, and 71% rarely spoke to their oncologists about cost. More than 71% of patients did not want either society’s or personal costs to influence treatment, and this result did not change based on degree of financial stress. Even when asked to assume that lower cost regimens were equally effective, only 28% would definitely want the lower cost regimen. Patients did not believe it was the oncologist’s duty to perform cost discussions.

Conclusion.

Even insured patients have a high degree of financial distress. Most, including those with the highest levels of distress, did not speak often with oncologists about costs and were strongly adverse to having cost considerations influence choice of regimen. The findings suggest that patients are not cost sensitive with regard to treatment decisions. Oncologists will require improved tools to have meaningful cost discussion, as recommended by the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Implications for Practice:

This study raises important questions regarding optimal communication with patients about costs. If patients are not cost sensitive regarding treatment decisions, they will not be full partners in the desire to reduce financial burden and financial distress by lowering costs. Better patient educational tools are needed to help increase not just cost awareness but also awareness of value. To master this mode of discourse and to help ease patients’ financial toxicity, oncologists will need to master a new set of data and develop new skills. This new knowledge and proficiency are as vital to good oncology care as all other clinical acumen.

Introduction

Increased attention is being paid to cancer care cost of illness, with regard to both society at large [1, 2] and the impact on individual patients’ financial wellness [3, 4]. Several overlapping or related terms have been used to describe the financial impacts of cost of illness on individual patients with cancer. Financial burden can be described as the impact that cancer has on personal financial wellness due to loss of family income and/or increased outlay of out-of-pocket medical and nonmedical expenditures [3]. Financial stress or distress conveys the extent of worry, anxiety, or anguish about financial decline, either anticipated or actually experienced. Such distress is correlated with poor patient satisfaction [3], higher rates of depression [5], and noncompliance [6, 7]. Financial toxicity is a newer term [8] analogous to the physical harm of treatment-related organ toxicity. It reflects recognition that there is a financial harm related to rendered treatments. Integral to this idea is that financial toxicity might be modified by choosing tests, procedures, and therapies with more consideration of a patient’s financial burden [8].

In recognition of these issues, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has urged earlier and more complete communication about costs between physicians and patients and has prepared resources to help with this dialogue [9, 10].

Less is known about patient attitudes regarding financial burden, distress, and toxicity and different methods to ameliorate it. Patients desire communication and education about care costs [11], but surveys suggest that less than 20% actually communicate with their oncologists about treatment costs [12, 13]. Moreover, even with a documented desire to communicate about costs of care, many questions about the best way to communicate remain unanswered. We sought to gain a greater understanding of what patients think about the issue of costs in relation to their own cancer care. We specifically sought to understand whether patients think that their oncologists should do the educating and communicating about costs of care. We also sought to understand whether patients think that costs, either their own or those of society at large, should be weighed in making treatment decisions. The answers to these questions are important to find optimal approaches to ameliorate the multiple dimensions of adverse financial effects.

Methods

Cancer patients in one of two treatment areas, the infusion clinic or the radiation oncology clinic at a regional multispecialty cancer center, were recruited by convenience sampling to complete a 30-question survey written in the English language that assessed patient attitudes about the financial burden of cancer care (supplemental online Appendix). The survey used both validated scales and novel items created specifically for this study. The areas of assessment included demographic characteristics, the financial burden of patients’ cancer care, the level of financial distress, and attitudes about willingness to consider the cost of care in treatment decisions. The institutional review board approved this study and the survey questions.

Measures

Participant Characteristics

Participants indicated the type of cancer with which they were diagnosed, when they were diagnosed (month and year), and the types of treatment they had or were receiving. Participants also reported their age, gender, marital status, household income, and health insurance types.

Financial Distress/Toxicity

The Personal Financial Wellness Scale is an 8-item validated scale that assesses participants’ perceptions about their personal financial situation [14, 15]. It has been used but not normalized with cancer patients [16]. Each item used a 10-point scale, and mean scores were computed that ranged from 1, indicating overwhelming financial distress, to 10, indicating no financial distress (α = .97). Recommended cut points were also used to categorize participants as having high distress (scores <4.4), average distress (scores 4.5–6.4), or low distress (scores >6.5).

A dichotomous item assessed whether participants had changed their spending habits (e.g., reduced leisure activity spending) as a result of the cost of their care. An additional item asked participants to assess the extent to which they agreed with the statement, “I believe that being sick has/will hurt me financially,” using a 5-point scale that ranged from 1, indicating strongly disagree, to 5, indicating strongly agree. A similar item was used by Head and Faul in their socioeconomic well-being scale for persons with cancer [17].

Patient-Doctor Communication

Participants provided a response using a 5-point scale ranging from 1, indicating rarely, to 5, indicating very frequently, to describe how often they talked with their oncologist about the cost of care. In response to a follow-up question, they indicated their top reason for not discussing the cost of care, choosing from a list that included six options: “I don’t think that’s her/his job,” “There is not enough time during clinic visits”, “I don’t want my doctor to think less of me,” “I don’t want my doctor to change therapies because of cost issues,” or “I don’t think the doctors are concerned about this aspect of care.”

Participants also indicated on a 5-point scale how well-informed they were about the cost of care at the start of their cancer treatment and whether they believed that information on personal financial costs of cancer should come from their oncologist.

Attitudes About Cost of Care

Three items assessed patients’ attitudes about considering the cost of care in treatment decisions, using a 5-point scale. These items were developed especially for this study, initially by a multidisciplinary group of experienced clinicians consisting of oncology physicians, nurses, social workers, and current patient advisers not currently under treatment. The survey was modified after the first eight patients provided feedback. These questions read as follows: “My personal financial situation should be a major factor in deciding among treatment options,” “Overall costs to society should be a major factor in deciding among treatment options,” and “If there were more than one treatment plan that were roughly the same in terms of effectiveness, I would want my doctor to prescribe the less costly one for me.”

Data Analysis Strategy

All reported analyses were conducted in Stata version 13 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, http://www.stata.com). We examined the prevalence of financial distress and then used generalized linear models specifying robust standard errors to test whether participant characteristics and facets of patient-doctor communication were associated with the level of financial distress. For dichotomous outcome variables, a Poisson distribution with a log link was specified. We tested the associations between financial distress and patient attitudes about considering the cost of care using the same analytic approach.

Results

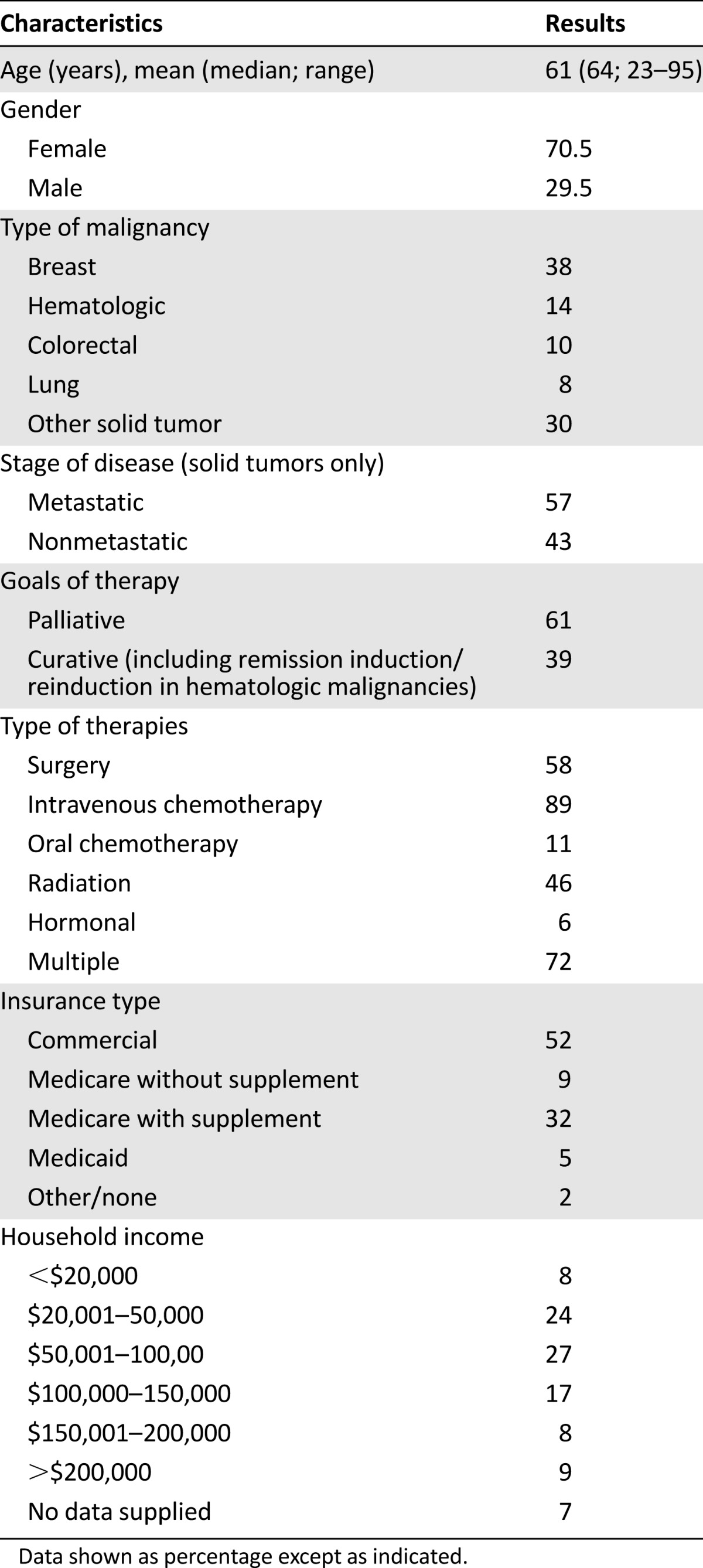

A total of 140 patients were approached, and 132 patients provided completed surveys (94%), including 8 that were completed several days after the survey was provided. Table 1 contains the demographics and characteristics of the 132 respondents. Not all patients answered every question. Most (73%) had been originally diagnosed with cancer in the previous year. Nearly all participants had some form of health insurance. Mean and median out-of-pocket costs were $938 and $250 monthly, respectively (range: $0–25,000).

Table 1.

Patient demographics (N = 132)

Extent of Financial Burden and Prevalence of Financial Distress and Toxicity

The average financial distress score was 5.11 (standard deviation 2.77), which reflects just slightly more distress than the general population, the mean score of which has been reported as 5.7 [15]. Nearly half of participants (47%) reported high levels of financial distress, as measured by the Personal Financial Wellness Scale. Consistent with this result, 50.4% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that being sick had hurt them financially, and 52.3% had changed their spending habits as a result of their treatment costs. A smaller proportion, 6.1%, had reduced medication adherence because of costs. One-quarter (25.8%) increased their debt, 22.0% became delinquent on personal bills, and 1.5% declared bankruptcy. Men were marginally more likely than women to agree that being sick had hurt them financially (b = 0.48; p = .085; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.068 to 1.04). Those with higher incomes were less likely to agree with that statement (b = −0.35; p < .001; 95% CI: −0.53 to −0.18). Marital status, insurance type, treatment type, and age were not associated with the perception that being sick had hurt them financially (p > .10 for all).

Prevalence of Feeling Well Informed and Discussing Costs With Oncologists

A minority of participants (30.8%) felt well informed about the costs of their cancer care prior to receiving treatment; however, most participants (73.1%) rarely talked to their primary oncologist about their own cost of care. Although men talked to their oncologist more frequently than women (p = .012), they were not more likely to feel well informed about costs than women. Indeed, there were no differences in feeling well informed with regard to age, gender, type of treatment, or income (p > .20 for all).

Controlling for gender and income, those who did feel well informed were less likely to report that the cost of care had hurt them financially (b = −0.19; p = .027; 95% CI: −0.36 to −0.021). Informed participants also had higher financial wellness scores (i.e., less financial distress; b = 0.38; p = .028; 95% CI: 0.041–0.73). Consequently, although few participants felt informed, those participants who did report feeling informed about their costs of care were less likely to report high levels of financial distress.

Patient Preferences for Discussing Cost of Care With an Oncologist

Only 20% of participants agreed that they should receive information about the costs of their care from their oncologist. The likelihood of agreeing with this item was not associated with participant characteristics, such as gender, age, marital status, income, and treatment regimen (p > .20 for all).

In addition, the belief that it was “not the oncologist’s job” was the top cited reason for not discussing the cost of care with their oncologist; however, patients with lower financial wellness were more likely to cite alternative reasons, such as concern about the doctor thinking less of them or concern that their doctor might alter their treatment regimen (risk ratio = 1.36; p = .005; 95% CI: 1.10–1.68). Other participant characteristics were not associated with any particular reason for not discussing costs.

Patient Attitudes About Modifying Treatment Regimens Based on Costs

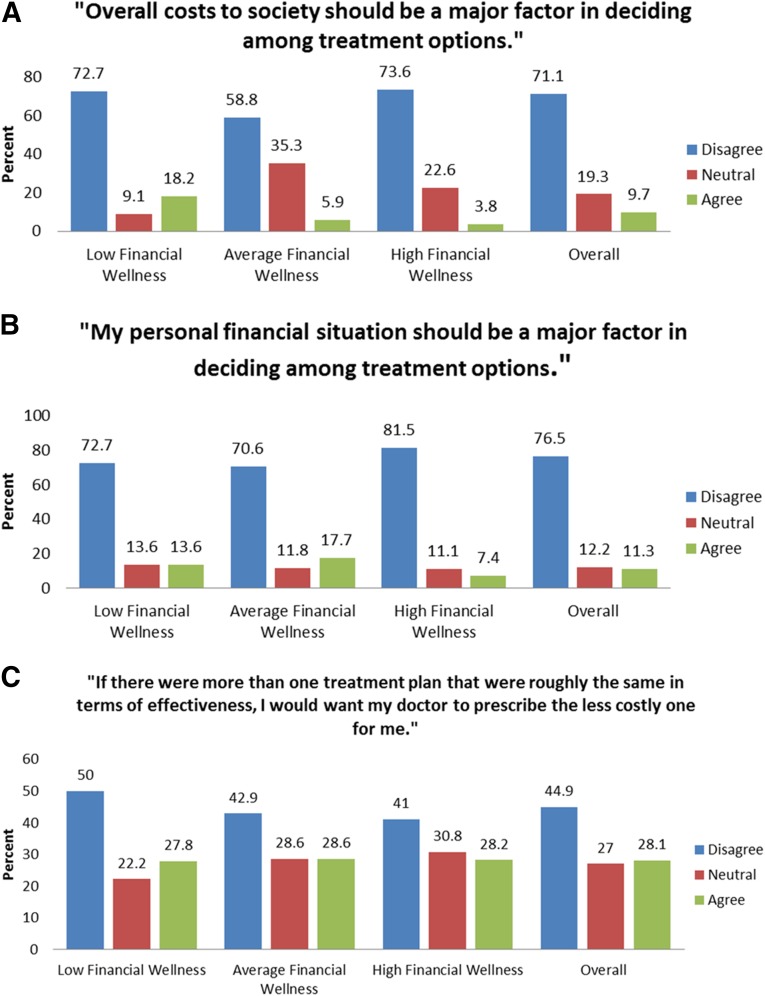

Figure 1 shows patient attitudes about modifying treatment based on costs stratified by degree of financial wellness.

Figure 1.

Patient attitudes regarding modifying treatment regimens based on overall costs to society (A), personal financial situation (B), and cost of treatment plan (C).

Few participants wanted their own personal financial situation (11%) or costs to society (10%) to be factors in deciding among treatment options. Financial wellness status was not associated with the likelihood of wanting one’s own personal financial situation to be a factor in treatment decisions (p = .22); however, lower financial wellness was associated with a lower likelihood of wanting costs to society to be a factor in treatment decisions (b = −0.11; p = .018; 95% CI: −0.20 to −0.019). Even when told to assume that lower-cost regimens were of equal effectiveness, only 28% of patients would want a lower-cost regimen to be prescribed.

Participants’ responses on the three questions about modifying regimens based on costs were highly correlated (r > .35 and p < .001 for all), suggesting consistency in their beliefs that the cost of care should not be considered, regardless of whether these costs are to themselves, to society, or considerations when deciding between two effective treatment regimens.

Discussion

That cancer care is associated with high financial burden for patients is not a new observation; however, the reframing of high out-of-pocket costs and the resulting distress of patients as a side effect or toxicity of cancer care [8, 18, 19] is a more recent and much-welcomed realization. The prevalence of this problem has been documented in different clinical settings, including some outside the U.S. [20, 21]. Our results on the prevalence and severity of financial distress and the use of cost-coping strategies among this insured population are similar to data gathered by previous surveys in different clinical populations. Zafar et al. [22] reported on an insured population, three quarters of which had requested drug copay assistance. They reported that 42% of patients noted “significant or catastrophic” financial burden, 46% cut back on other spending, and a similar percentage were forced to reduce savings to pay out-of-pocket expenses. Bestvina et al. [12] found that 27% of patients used one or more types of medication nonadherence to reduce costs.

Our findings on patient attitudes about costs indicate that patients do not desire to have treatment costs—either society’s or their own—influence treatment decisions. This preference holds true regardless of the degree of financial distress (Fig. 1). Even when cheaper alternatives were described as equally efficacious, only one patient in four desired the lower-cost therapy, and this proportion was unaffected by patients’ levels of financial distress. Even those with higher levels of financial distress reported a strong and pervasive desire not to have costs considered in choosing therapies.

To our knowledge, only one other study has addressed the issue of patient attitudes about treatment regimen selection based on personal or societal costs. Our results are similar to those of Bullock et al. [23], who found that a minority (34%) agreed or strongly agreed that personal out-of-pocket costs should be considered in treatment decisions, and even fewer (24%) felt the same way about societal cost burden. These findings indicate that patients, even financially distressed patients, are not cost sensitive in their approach to treatment decisions.

It is unclear why such attitudes exist even among those who have a high level of financial distress. There may be a bias among patients toward newer and more expensive therapies. The same phenomenon exists for many consumer products and luxury goods, for which consumers infer information about the value of a product or service from its cost. In addition, advertising, both of cancer treatment programs and of cancer medications, may play a role in reinforcing this bias [24]. Another bias may exist in the belief that there is a single best therapy that exists for the condition that is desirable regardless of cost, an assertion that is only sometimes true. Patients may prefer expensive newer therapies if they anticipate suffering regret if their cancer worsens after lower-cost therapy.

Our findings also confirm the low frequency of cost discussions reported by patients. Although 47% of oncologists indicated that they “always or frequently” discuss costs [24], patient surveys indicate this happens less than 25% of the time [11, 23, 25, 26].

In contrast to other work [11, 23] we found that patients were willing to have cost communication with other people in other roles and do not necessarily desire it with their physicians, most often because the patients do not think it is the doctor’s job to do so. Among patients with low financial wellness, an interesting feature of avoidance is the fear that the doctor will think poorly of them or that the regimen might be modified to their detriment.

These findings place in new light the expert ASCO guideline statement on cancer costs [11] and other recommendations including financial counseling as an integral part of cancer care [27]. Whether or not patients desire this dialogue with their physicians, the finding that patients may not be cost-sensitive in their treatment decisions means that ameliorating financial toxicity through better pretreatment cost disclosure and shared decision making may be harder than envisioned. These data behoove the oncology community to develop and test better tools that explain the complex interactions of cost and clinically meaningful outcomes. In addition, more research is critical to understand what factors influence patient attitudes and beliefs about clinical benefit and cost.

Our study is limited by the fact that it was an English language tool only and was completed exclusively by outpatients undergoing active therapy. Patients who were on oral therapy only or those who had completed active treatment were not approached; therefore, some patients may not have been experiencing the full financial impact of care at the time of the survey. In addition, we did not follow patients longitudinally to see if financial distress changed over time or if it correlated with duration of active therapy. Others have shown that financial burden can be long lasting [28, 29]. As such, this work and other research like it should be viewed as a “snapshot” of patient attitudes. Patients at different points in their treatment plan or life expectancy might offer different opinions. A convenience sample will identify a blend of such factors. In addition, most patients completed the survey in a single setting during a clinic visit, so they may have estimated—perhaps imprecisely—their out-of-pocket costs from memory rather than based them on personal financial records. Finally, responses to surveys are known to be influenced by subtle alterations in the order of questions or the ranking of responses [30], and this may account for some of the differences between our results with regard to lack of interest in discussing cost with oncologists and the results of other studies.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the nurses of the DeCesaris Cancer Institute for their interest in this research and excellent patient care.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Blair Irwin, Gretchen Kimmick, Ivy Altomare et al. Patient Experience and Attitudes Toward Addressing the Cost of Breast Cancer Care. The Oncologist 2014;19:1135–1140.

Implications for Practice: The 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology cost of cancer care guidance statement recommends that physicians and patients should communicate about costs as a means of decreasing overall spending and minimizing patients’ financial burden. This study suggests that the impact of costs of breast cancer care can be profound and that patients want to discuss direct out-of-pocket costs with their oncologists in the clinic. This study also finds that patient-physician communication about the societal costs of cancer care is not widely accepted by patients. Whether such discussions should occur or will have any role in controlling health care spending remains to be determined.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Barry R. Meisenberg, Ashley Varner, Stephen Ebner, Erika Siegrist, David Weng

Provision of study material or patients: Barry R. Meisenberg, Erin Ellis, Stephen Ebner, Erika Siegrist, David Weng

Collection and/or assembly of data: Barry R. Meisenberg, Ashley Varner, Erin Ellis, Stephen Ebner, John Moxley, Erika Siegrist, David Weng

Data analysis and interpretation: Barry R. Meisenberg, Ashley Varner, Erin Ellis, Stephen Ebner, John Moxley, Erika Siegrist, David Weng

Manuscript writing: Barry R. Meisenberg, Ashley Varner, Erin Ellis, John Moxley, Erika Siegrist, David Weng

Final approval of manuscript: Barry R. Meisenberg, Ashley Varner, Erin Ellis, Stephen Ebner, John Moxley, Erika Siegrist, David Weng

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2060–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1013826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuehn BM. Economist: It’s time for tough choices on US health costs. JAMA. 2014;311:2469–2470. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chino F, Peppercorn J, Taylor DH, Jr, et al. Self-reported financial burden and satisfaction with care among patients with cancer. The Oncologist. 2014;19:414–420. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley CJ. Financial hardship: A consequence of survivorship? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1579–1580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharp L, Carsin A-E, Timmons A. Associations between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:745–755. doi: 10.1002/pon.3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, et al. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:306–311. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.9123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zullig LL, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. Financial distress, use of cost-coping strategies, and adherence to prescription medication among patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:60s–63s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ubel PA, Abernethy AP, Zafar SY. Full disclosure--out-of-pocket costs as side effects. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1484–1486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Financial considerations. Available at http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/financial-considerations. Accessed December 8, 2014.

- 11.Kaser E, Shaw J, Marven M, et al. Communication about high-cost drugs in oncology--the patient view. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1910–1914. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:162–167. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irwin B, Kimmick G, Altomare I, et al. Patient experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of breast cancer care. The Oncologist. 2014;19:1135–1140. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, et al. InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: Development, administration, and score interpretation. J Financial Counseling Plann. 2006;17:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen RB. Assessing financial wellness via computer-assisted telephone interviews. J Financial Counseling Plann. 2010;21:16–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Souza JA, Wong Y-N. Financial distress in cancer patients. J Med Pers. 2013;11:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s12682-013-0152-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Head BA, Faul AC. Development and validation of a scale to measure socioeconomic well-being in persons with cancer. J Support Oncol. 2008;6:183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: A new name for a growing problem. Oncology (Williston Park) 2013;27:80–81, 149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120:3245–3253. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Longo CJ, Fitch M, Deber RB, et al. Financial and family burden associated with cancer treatment in Ontario, Canada. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:1077–1085. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kodama Y, Morozumi R, Matsumura T, et al. Increased financial burden among patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia receiving imatinib in Japan: A retrospective survey. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:152–161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. The Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, et al. Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e50–e58. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vater LB, Donohue JM, Arnold R, et al. What are cancer centers advertising to the public?: A content analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:813–820. doi: 10.7326/M14-0500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumann PJ, Palmer JA, Nadler E, et al. Cancer therapy costs influence treatment: A national survey of oncologists. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:196–202. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly RJ, Forde PM, Bagheri A, et al. Measuring the impact of chemotherapy cost discussions between patients and providers at the time of prescribing. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(suppl 31):257a. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shankaran V, Ramsey S. Addressing the financial burden of cancer treatment. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:273–274. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al. Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: Experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1269–1276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, Guy GP, Jr, et al. Medical costs and productivity losses of cancer survivors--United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:505–510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwarz N. Self-reports: How the questions shape the answers. Am Psychol. 1999;54:93–105. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.