Abstract

Purpose of the Study:

Research shows that parents benefit psychologically from generativity—giving and caring for the next generation—but older adults’ perceptions on giving support to their children are rarely if ever explored in these studies. The current study examines the association between the support that aging parents give to one of their middle-aged offspring, their perception of this support as rewarding or stressful, and their levels of depressive symptoms.

Design and Methods:

The sample draws from The Family Exchanges Study and consisted of 337 older parents (mean age: 76) who were drawn from a larger study of middle-aged adults (i.e., target participants). Older parents reported tangible and nontangible forms of support given to the target middle-aged child and the extent to which they viewed providing such support as stressful and/or rewarding.

Results:

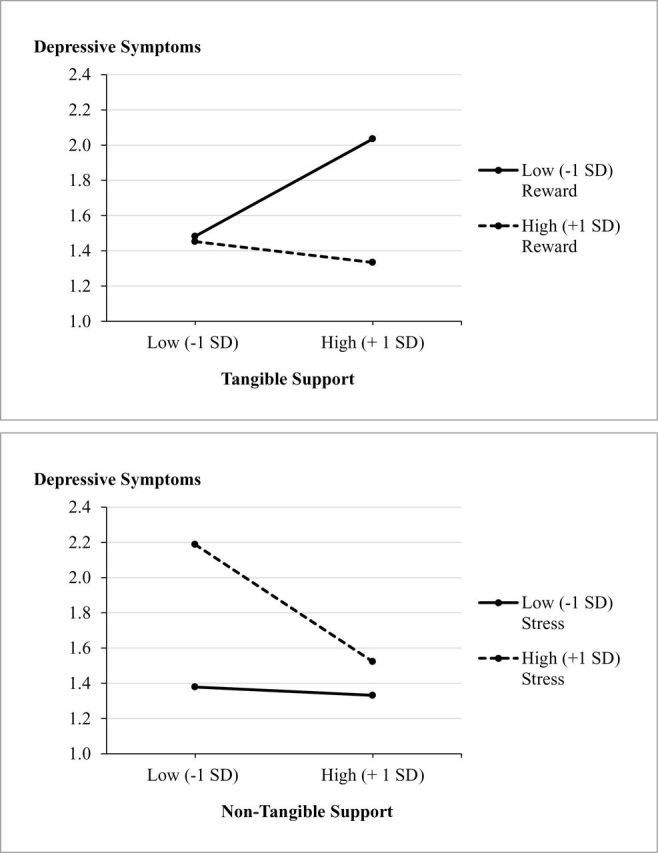

We found significant interactions between tangible support and feelings of reward and between nontangible support and feelings of stress in explaining parental depressive symptoms. Parents who found giving support to be highly rewarding had lower levels of depressive symptoms when giving high amounts of tangible support. Conversely, parents who view giving support to be highly stressful had higher levels of depressive symptoms when they gave low amounts of nontangible support.

Implications:

Findings suggest older parents’ perceptions of supporting their offspring may condition how generativity affects their mental health.

Key Words: Depression, Parent/child relationships, Quality of life, Generativity

Parents serve as a consistent source of support for their adult children, frequently providing advice, practical assistance, and financial transfers (Bucx, van Wel, & Knijn, 2012; Fingerman, Miller, Birditt, & Zarit, 2009). Although age may condition the types of support that parents give to their children (Bucx et al., 2012; Hartnett, Furstenberg, Fingerman, & Birditt, 2012), it seems that even when their children are grown, many parents continue providing various types of support. Yet, few studies have explored how giving different types of support to adult offspring impact aging parents’ depressive symptoms (Liang, Krause, & Bennett, 2001).

Several studies have found that adults regularly engage in and psychologically benefit from generativity. Generativity refers to a concern for establishing, guiding, and contributing to the welfare of future generations (An & Cooney, 2006) and is commonly manifested within the family through tangible support exchanges (Fingerman et al., 2009) and transmission of values (Pratt, Norris, Hebblethwaite, & Arnold, 2008) or outside of the family through volunteerism and societal engagement (Son & Wilson, 2011). However, it is enacted, generativity has many implications for health in later life. Greater perceptions of generativity are associated with fewer activities of daily living disabilities (Gruenewald, Liao, & Seeman, 2012). Other research shows that providing emotional support may also act as a double-edged sword: Contributing to the positive emotions of others is associated with fewer depressive symptoms, whereas listening to the problems and conflict of others is associated with an increase in depressive symptoms (Strazdins & Broom, 2007). Providing more types of support is associated with greater well-being for older adults, whereas providing support to a greater number of family members was negatively associated with well-being (Thomas, 2010).

Previous research has generally distinguished between instrumental and emotional support (A. S. Rossi & P. H. Rossi, 1990; B. A. Sarason, I. G. Sarason, & Pierce, 1990; Vaux, 1988) as having unique functions and serving distinct purposes. Providing emotional support predicts greater self-esteem and control beliefs among elderly adults with comorbid health conditions (Warner, Schuz, Wurm, Ziegelmann, & Tesch-Romer, 2010). Provision of practical support through volunteerism and civic engagement is associated with higher quality of life for older adults (Wheeler, Gorey, & Greenblatt, 1998). The psychological functions of giving each type of support have yet to be thoroughly explored in the context of family exchanges (Gutierrez, Tomas, Galiana, Sancho, & Cebria, 2013).

The purpose of this study is to examine how giving different types of support to adult offspring is associated with the mental health of aging parents and whether perceiving giving support as stressful or rewarding moderates the association between giving support and depressive symptoms. By examining these associations, we can better understand possible psychological implications and motivations of generativity in later life. We can also gain a sense of how different forms of support are associated with psychological well-being of older parents. By focusing on the giver, rather than the receiver of support, this study adds a unique perspective to research on generativity and for understanding associations between parental giving and mental health in late life.

Providing Support and Mental Health

Parents are perhaps the most obvious source of support for children when they are young, however as children mature into adults, parents remain an important support system, providing instrumental, financial, and emotional help (Bucx et al., 2012; Fingerman et al., 2009). These general patterns of support are enacted in many ways including household chores, transportation or shopping, giving information, discussion of important life decisions, visiting or sharing of leisure activities, assisting with personal care, giving advice, exchanging services, or providing financial assistance (Eggebeen, 1992; Lin, 2004; Silverstein, Gans, & Yang, 2006).

Taken as a whole, the existing literature concerning family support exchanges demonstrates many forms of support that can be conceptualized as tangible and nontangible support. Tangible support represents material, instrumental, or concrete support given or received by an individual. Nontangible support assesses a psychological and emotional form of support that is not measured through material transfers. Both forms of support remain important in our understanding of generativity and family support exchanges, however they are indeed distinct and examining how these forms of support differ may prove insightful to existing research.

Literature suggests that parents benefit psychologically from giving different types of support to their children, at least in cultures that place a high value on family and collectivism (Cruza-Guet, Spokane, Caskie, Brown, & Szapocznik, 2008). For example, Chen and Silverstein (2000) found that among older Chinese parents, providing personal support—such as housework or babysitting—to adult offspring was associated with better morale, whereas providing financial assistance had no effect on parent morale. In Western cultures, the experience of giving instrumental or financial support may be distinct from the experience of giving more nontangible, emotional types of support. In the United States, parents who provide financial and instrumental support to grown children may do so in response to their children’s needs (Fingerman et al., 2009) and may experience stress and negative emotions in doing so. By contrast, providing emotional support may occur in the context of loving relationships where those giving support may feel positive emotions as a result of the support they give to others. Thus, it is plausible that how one perceives the support exchange moderates the association between giving and mental health.

The present study sought to give insight into how aging parents’ perceptions of giving support to an adult child are associated with depressive symptoms. We examined how the experience of giving support as either rewarding or stressful moderated the potential impact that giving tangible and nontangible support has on depressive symptoms of older parents. Of course, in a cross-sectional study, patterns of association may be reversed, and people who are in better mental health may perceive less stress in providing support. Nonetheless, theory suggests that providing the support and conditions for providing support may have implications for mental health outcomes, and we tested this theory here. Further, we considered tangible and nontangible support as distinct types of support. We hypothesized that parents who perceive giving support to be highly rewarding would report lower levels of depressive symptoms when they gave high amounts of support. Likewise, we anticipated that parents who perceive giving as highly stressful would have higher levels of depressive symptoms when they are giving high amounts of support.

Methods

Sample

Data were utilized from The Family Exchanges Study (FES; Fingerman et al., 2009). FES recruited a target sample of 633 middle-aged adults (M = 50.60, SD = 4.99) who had at least one living adult child and at least one living parent in 2008. These participants were identified through phone lists from Genesys Corporation and random digit dialing from the Philadelphia Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area (PMSA) including urban, rural, and suburban areas in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Participants completed 1-hr long Computer Assisted Telephone Interviews (CATIs) regarding relationships with their grown offspring and living parents. These target participants provided the names and contact information of their living parents.

From the original sample of middle-aged adults, 280 (44%) had parents who agreed to be interviewed. In 223 cases, one parent was interviewed, and in 57 cases, both parents were interviewed, which yielded 337 dyads of parent and target offspring. This paper utilizes data from this sample of 337 older parents. The parent sample completed CATIs similar to the interviews completed by the target child. These interviews lasted 30min on average. Parents answered questions about each of their living children including the target child from the original sample. Questions focused on exchanges of support, beliefs about relationships with children, and other demographic information. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the parents interviewed for this study. Participant age ranged from 59 to 96 (M = 76.07, SD = 6.32). About 69.4% of participants were female and 30.6% were male. Parents answered many questions about each of their grown children, but they only provided ratings of the target child for a subset of questions regarding rewards and stress of providing support. Thus, this study focused on ties to the target child. The target children differed from other children with regard to gender and age; target children are more likely to include daughters (χ2 = 11.12, p < .01) and older children (t = −4.88, p < .001), compared to other children.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Parental Characteristics

| Characteristics | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 76.07 | 6.32 | 59–96 |

| Male, n (%) | 103 | 30.6 | — |

| Racial minority, n (%) | 119 | 35.5 | — |

| Married/remarried, n (%) | 159 | 47.2 | — |

| Number of adult children | 3.93 | 2.00 | 1–12 |

| Relationship quality with target childa | 4.51 | 0.74 | 2–5 |

| Years of education | 12.71 | 2.49 | 0–17 |

| Household income | 3.01 | 1.31 | 1–6 |

| 1. <$10,000, n (%) | 33 | 10.8 | — |

| 2. $10,001–$25,000, n (%) | 91 | 29.7 | — |

| 3. $25,001–$40,000, n (%) | 74 | 24.2 | — |

| 4. $40,001–$75,000, n (%) | 72 | 23.5 | — |

| 5. $75,001–$100,000, n (%) | 19 | 6.2 | — |

| 6. >$100,000, n (%) | 17 | 5.6 | — |

| Self-reported healtha | 3.08 | 1.12 | 1–5 |

| 1. Poor, n (%) | 24 | 7.1 | — |

| 2. Fair, n (%) | 90 | 26.7 | — |

| 3. Good, n (%) | 96 | 28.5 | — |

| 4. Very good, n (%) | 90 | 26.7 | — |

| 5. Excellent, n (%) | 37 | 11.0 | — |

Notes: N = 337.

a1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, and 5 = excellent.

Measures

Support Given to Adult Offspring.

The study used six items from the Intergenerational Support Scale (ISS; Fingerman et al., 2009), which measures how frequently parents report giving different types of support to each of their children: companionship, talking about daily events, emotional support, practical support, giving advice, and financial assistance. Participants rated how frequently they provided these types of support to their living adult children on an 8-point scale ranging from 1 (less than once a year or not at all) to 8 (daily).

For the purposes of this study, we grouped these items into two general types of support: tangible and nontangible support. As presented in Table 2, each type of support was examined separately before being categorized as either nontangible or tangible support. Tangible support was established by computing the mean of practical support and financial assistance (two items), which represents material or concrete support (i.e., fixing something around the house, running an errand, providing a ride, giving money, loaning money, and helping to purchase goods, services, insurance, or education). Nontangible support is the mean score of emotional support, companionship, talking about daily events, and advice (four items), which assesses a psychological and perhaps more subtle form of generativity (i.e., listening to concerns or being available when a child is upset, helping with a decision or providing suggestions about things they could do). The resulting measures of the two types of support are consistent with prior studies (e.g., A. H. Rossi & P. S. Rossi, 1990; Silverstein et al., 2006). The reliabilities of the support measures were 0.52 for tangible support and 0.75 for nontangible support.

Table 2.

Parent’s Report of Support Given to Target Child

| Total (N = 337) | Mother (n = 234) | Father (n = 103) | t | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||

| Tangible supporta | 2.69 | 1.60 | 2.72 | 1.65 | 2.62 | 1.48 | 0.52 |

| Practical support | 3.39 | 2.28 | 3.45 | 2.32 | 3.25 | 2.19 | 0.75 |

| Financial support | 2.01 | 1.53 | 2.02 | 1.57 | 1.99 | 1.45 | 0.17 |

| Nontangible supporta | 4.72 | 1.48 | 4.90 | 1.47 | 4.31 | 1.41 | 3.46** |

| Emotional support | 4.86 | 2.18 | 5.13 | 2.07 | 4.27 | 2.31 | 3.35** |

| Advice | 3.91 | 2.04 | 4.06 | 2.07 | 3.57 | 1.94 | 2.05* |

| Companionship | 4.42 | 1.80 | 4.56 | 1.81 | 4.10 | 1.74 | 2.18* |

| Talking about daily life | 5.71 | 1.77 | 5.89 | 1.74 | 5.31 | 1.80 | 2.80** |

| Giving is rewardingb | 4.29 | 0.89 | 4.34 | 0.81 | 4.16 | 1.04 | 1.80 |

| Giving is stressfulb | 1.59 | 1.09 | 1.59 | 1.11 | 1.59 | 1.04 | −0.19 |

Notes: a1 = less than once a year or not at all, 2 = once a year, 3 = a few times a year, 4 = monthly, 5 = a few times a month, 6 = weekly, 7 = a few times a week, and 8 = daily.

b1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = somewhat, 4 = quite a bit, and 5 = a great deal.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

Depressive Symptoms.

We assessed depressive symptoms of parents, using five items from the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), a 53-item self-report scale (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), which measures depressive symptoms commonly observed in everyday settings. Parents rated to what extent they felt lonely, blue, worthless, hopeless about the future, or had no interest in things, using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Individual depressive symptom scores were established by computing the mean score of these five items (α = 0.78).

Perceptions of Giving.

To account for parents’ perceptions of giving support, we included both a measure of stress and a measure of reward in our analysis. Parents rated: (a) how stressful they found giving support to the target child as well as (b) how rewarding they found giving support to the target child. The answers were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal).

Control Variables.

We controlled for three demographic characteristics of older parents associated with mental health or support exchanges: age, gender, and self-rated health. Amount of emotional support exchanged between parents and children has been found to decrease with parent’s chronological age (Keyes, 2002). We also controlled for parent gender (coded 1 for male and 0 for female) because previous research shows that mothers and fathers have very different relationships with their children (Burholt & Wenger, 1998). Because self-rated health has shown a strong association between mental health and physical health in old age (Efklides, Kalaitzidou, & Chankin, 2003; Kay & Bergman, 1966; Zubenko et al., 1997), we also included self-rated health for the past 12 months as a control variable. Self-rated health was rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent). On average, participants rated their health to be good (M = 3.07, SD = 1.12).

In addition to demographic variables, we controlled for the mean levels of tangible and nontangible support given to all children to ensure that results were not influenced by other relationships than the target child within the family. We also chose to control for the number of children so that family size did not condition the amount of support that a parent was able to give to the target child. Less positive relations with children have been found to be related to low levels of parent well-being (Ward, 2008). Also, the relational quality between the parent and the child may affect how parents provide support (Fingerman et al., 2009). Thus, we controlled for relational quality between the parent and their target child rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent) in the model.

Analysis Strategy

Multilevel regression models were conducted to predict the level of depressive symptoms of older parents, using the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS (Littell, Milliken, Stroup, & Wolfinger, 1996). The multilevel models take into account the nested nature of the data and handle correlated error in parents from the same families (n = 114).

The predictors included two types of support given to the target (i.e., tangible and nontangible) and two perceptions of giving support (i.e., giving is stressful and giving is rewarding). After centering variables, we also computed possible interactions between support given and perceptions of giving support. We did this to examine whether viewing support as stressful or rewarding moderates the association between the support that parents give and parental depressive symptoms. We present the significant interaction terms, trimming nonsignificant interaction terms. We controlled three parental characteristics (i.e., age, gender, and self-rated health), relationship quality with adult offspring, and three family characteristics (i.e., number of adult children, tangible support given to all children, and nontangible support given to all children) in the analyses.

Analyses focused on four research aims: (a) revealing the patterns of tangible and nontangible support that aging parents provide to their child, (b) examining how parents perceive giving support to the target child (as stressful or rewarding), (c) describing the association between giving support and depressive symptoms of older parents, and (d) understanding how perceptions of giving as either a stressful or rewarding experience influences the association between providing tangible and nontangible support and depressive symptoms.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

We first examined how frequently participants provided support to their offspring and how they perceived the support that they give to the target child (Table 2). The most frequent forms of support parents provided were talking about daily life (M = 5.71, SD = 1.77) and emotional support (M = 4.86, SD = 2.18). Parents reported providing practical support (M = 3.39, SD = 2.28) and financial support (M = 2.01, SD = 1.53) least frequently. When these individual forms of support were categorized into tangible and nontangible support, nontangible support was more frequently provided (M = 4.72, SD = 1.48) and tangible support was provided less often (M = 2.69, SD = 1.60).

Parents reported their perceptions of giving to the target child as either stressful or rewarding. As shown in Table 2, feelings of reward were relatively high (M = 4.29, SD = 0.89). In contrast, parents indicated a lower level of stress surrounding giving (M = 1.59, SD = 1.09).

Gender differences in the levels of support provided and perceptions of giving are also reported in Table 2. Overall, mothers reported giving nontangible support more frequently than fathers. However, giving tangible support and perceptions of giving did not differ by gender.

Regarding depressive symptoms among parents (data not shown in table), participants reported relatively low levels of depressive symptoms (M = 1.45, SD = 0.63). We did not find gender differences in the level of depressive symptoms.

Table 3 shows correlations of all predictor variables. Tangible support and nontangible support given to the target child were significantly positively correlated as was tangible and nontangible support given to all children. Other significant correlations include the correlation between stress and tangible support given to the target child and all children as well as reward and relational quality with the target child.

Table 3.

Correlations Among Predictor Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Tangible support given to target | — | |||||||||

| 2. Nontangible support given to target | 0.60*** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Reward | 0.01 | 0.15* | — | |||||||

| 4. Stress | 0.20*** | 0.06 | −0.13* | — | ||||||

| 5. Gender (1 = male) | −0.03 | −0.19** | −0.10 | 0.00 | — | |||||

| 6. Age | −0.19*** | −0.17** | −0.16** | −0.08 | 0.19*** | — | ||||

| 7. Self-reported health | 0.02 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 | — | |||

| 8. Number of adult children | −0.10 | −0.08 | 0.01 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.17** | — | ||

| 9. Relationship quality with target child | −0.05 | 0.13* | 0.32*** | −0.42*** | 0.13* | 0.14* | 0.22*** | −0.07 | — | |

| 10. Tangible support given to all children | 0.84*** | 0.52*** | 0.02 | 0.20*** | −0.04 | −0.19*** | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.08 | — |

| 11. Nontangible support given to all children | 0.52*** | 0.76*** | 0.09 | 0.06 | −0.18** | −0.12* | −0.09 | −0.04 | 0.05 | 0.68*** |

Notes: N = 337.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Multilevel Models for Depressive Symptoms

Multilevel regression examined the association between giving support and levels of parental depressive symptoms (Table 4). We found two significant interactions associated with depressive symptoms. First, the interaction of feelings of reward and giving tangible support was significant for depressive symptoms (B = −0.05, p < .05). To examine this interaction, we first categorized participants as feeling high stress or low stress and giving high nontangible or low nontangible by fixing them to +1 SD and −1 SD from their mean. After categorizing parents as feeling high or low reward and high or low tangible support, we found that parents who found giving support to be less rewarding showed higher levels of depressive symptoms when they are providing more tangible support (Figure 1). In contrast, greater tangible support was associated with lower depressive symptoms among people who found support highly rewarding.

Table 4.

Multilevel Regression Models for Parent Depressive Symptoms

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | B | SE | |

| Fixed effect | ||||

| Intercept | 1.46*** | 0.04 | 1.46*** | 0.04 |

| Support given to target child | ||||

| Tangible support | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Nontangible support | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Perception on giving support to target child | ||||

| Reward | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.04 |

| Stress | 0.13*** | 0.03 | 0.13*** | 0.03 |

| Interactions | ||||

| Tangible support × Reward | — | −0.05* | 0.02 | |

| Nontangible support × Stress | — | −0.05* | 0.02 | |

| Controls | ||||

| Gender (1 = male) | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.00 | 0.07 |

| Age | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Self-reported health | −0.14*** | 0.03 | −0.13*** | 0.03 |

| Number of adult children | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.00 | 0.02 |

| Relationship quality with target child | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.00 | 0.05 |

| Tangible support given to all children | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Nontangible support given to all children | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Random effect | ||||

| Intercept variance | 0.10* | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Residual variance | 0.25*** | 0.05 | 0.25*** | 0.05 |

| −2 Log-likelihood | 644.6 | 644.6 | ||

Notes: N = 337.

*p < .05. ***p < .001.

Figure 1.

Two interaction effects between perceptions regarding giving support to the target offspring (i.e., reward and stress) and types of support given (i.e., tangible and nontangible support) on depressive symptoms of older parents.

Second, we also found a significant interaction effect between stress and giving nontangible support on depressive symptoms (B = −0.05, p < .01). Parents who found giving support to be highly stressful had fewer depressive symptoms when they give more nontangible support. However, parents who reported lower levels of stress had higher levels of depressive symptoms when they are giving more nontangible support (Figure 1).

Two interactions were not significant including the interaction between stress and tangible support as well as the interaction between reward and nontangible support. Among the covariates, only self-reported health was significant, with better subjective health associated with fewer depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Perceptions of giving tangible and nontangible support to adult children may have psychological implications for aging parents. Giving may increase feelings of generativity, which leads to these effects on mental well-being. Although past research shows that giving support declines with age (Keyes, 2002), our data show that parents frequently provide both tangible and nontangible support to their grown children. Furthermore, a clear pattern of giving emerged from this sample: Parents reported providing nontangible support more frequently than tangible support. These results were somewhat intuitive because tangible forms of support (e.g., financial and practical assistance) are finite, whereas nontangible forms of support (e.g., emotional support and advice) are not necessarily limited by the material or physical resources available.

It is likely that the age of parents in our sample played a role in the types of help that they are able to provide their children. For example, older parents may be on a fixed income that may prevent them from providing frequent financial support to their adult children. Although we controlled for self-reported health, other physical limitations may prevent parents from providing practical assistance to their children; assisting with driving or household chores may not be possible for older parents. Conversely, older parents possess many life experiences that contribute to their ability to give nontangible support to their grown offspring. After experiencing many life events, older parents may feel inclined to share knowledge and advice with others, especially to their children.

The data also confirm that while parents provide different types of support to their grown offspring, this support is coupled with feelings of both stress and reward, albeit stress levels were low on average. The negative correlation between stress and reward (Table 3) suggests that parents may harbor specific attitudes pertaining to the support that they give. Although participants reported higher levels of reward than stress, our results do in fact indicate that providing support to adult offspring is interpreted and experienced in unique ways in different families. Although we were unable to measure levels of stress and reward for specific types of support, our analysis indicates that perception of giving as a whole is a valuable consideration for intergenerational family support exchange research.

Consistent with previous research on giving support to a loved one (Inagaki & Eisenberger, 2012), our results indicate that the provision of support may be beneficial to parents and may promote a sense of purpose or satisfaction from being able to continue helping one’s children, in effect, what Erikson described as generativity (Erickson, 1963). But giving support by itself was not sufficient. Rather, parents’ perceptions of giving and the type of support that they provide their offspring have a significant association with depressive symptom levels. The mental health implications associated with giving support to grown children take on a new and important meaning when analyzed within the context of how parents perceive the experience of giving.

Within our sample, viewing giving as a highly rewarding experience moderates the association between parent depressive symptoms and tangible support. When feelings of reward were high, parents who gave low amounts of tangible support had higher levels of depressive symptoms, whereas parents who gave high amounts of tangible support had lower levels of depressive symptoms. In contrast, parents who did not view giving as highly rewarding reported higher levels of depressive symptoms when they gave high amounts of tangible support. In both of these cases, we see that depressive symptoms are more frequent when the level of reward (low/high) a parent feels is inconsistent with the amount of tangible support that they actually give (low/high).

When examining interactions between stress, nontangible support, and depressive symptoms, we see different results. Parents who view giving as a highly stressful experience have the highest levels of depressive symptoms when giving low amounts of nontangible support to the target offspring. Although giving may be a stressful experience, the long-term implications for providing support seem to persist when a parent is giving nontangible support to their child. Perhaps providing low amounts of nontangible support indicates that there are few opportunities to make such contributions to a child’s life and fulfill parental duties. Interestingly, parents who view giving as highly stressful and gave high amounts of nontangible support had fewer depressive symptoms. These somewhat paradoxical findings are consistent with reports by Strazdins and Broom (2007) that giving emotional support can increase depressive symptoms, when the support is given in the context of problems or conflict. It is possible that parents who find giving nontangible support stressful and give high amounts of support are more engaged generally with their child and have opportunities to address both problems and positive issues in their child’s life, whereas parents giving a little support are drawn in only when there are problems.

Barriers to providing tangible and nontangible support are plentiful; providing tangible assistance may be outside the means of many elderly parents while some adult children may refuse or not welcome nontangible support from their elderly parents. Conversely, giving a lot of nontangible support even when it is stressful to do so is associated with fewer depressive symptoms than giving a little support. Further study is needed to determine factors that lead to feelings of stress in giving nontangible support and how the amount and type of support given affects well-being.

Implications and Conclusions

This study provides potential directions for future research concerning intergenerational relationships, familial support, and depressive symptoms in older parents. Specifically, our results indicate the potential to focus on the psychological perceptions of giving support. This study provides unique insight into the implications of generativity; older parents may provide support not only because their children benefit from receiving support, but also that it may fulfill feelings of parental obligation. Thus, it may be wise to consider the role that parental obligation plays in future studies pertaining to parental generativity.

These findings support the notion that social and behavioral factors may improve the mental health and quality of life of older adults (Glymour & Osypuk, 2012) and raise important questions concerning the role that support given by older adults plays outside of the family context. Results also suggest that depending on their perceptions of giving, older adults may benefit from making tangible or nontangible contributions to younger generations. Thus, future research concerning intergenerational support exchanges could be utilized in the planning and implementation of health promotion programming for older adults. One such program, Experience Corps, has proven to be quite successful in improving physical and cognitive activity in older adults as well as educational outcomes for children (Fried et al., 2004). A greater understanding of how intergenerational social relationships may impact mental health in late life is greatly needed in order to establish health promotion programming and interventions for this population.

Some limitations warrant comment. Limitations of giving support must be taken into consideration such as resources available to parents and the needs of offspring. These variables were not considered in the present analysis but should be considered in future research. Another limitation is that our data only capture the support exchange relationship between a parent and one of their adult children. Expanding analysis to focus on support exchanges between older parents and all of their children would reveal interesting insight into within and between family differences concerning generatively. Our analyses are limited, in that, reports are only provided by a parent which may bias our results in some respect. Thus, it would be useful to examine both children’s and parent’s reports of support exchanges and their perspectives of giving different types of support. Another limitation is the low rates of depressive symptoms among the parents in our sample. Although the skewed depressive symptom measure did not prove to be problematic in our analysis, it would be beneficial for the depressive symptoms measure to reflect a normal distribution. These limitations should inform future research with the ultimate goal of strengthening our understanding of intergenerational support exchanges.

Funding

This work was supported by grant R01 AG027769, “The psychology of intergenerational transfers” (PI: K. L. Fingerman, PhD) and grant K99/R00 AG029879, “Promoting well-being across adulthood: The role of conflict avoidance” (PI: K. S. Birditt, PhD) from the National Institute of Aging as well as a grant from the MacArthur Network on Transitions to Adulthood (Director: Frank F. Furstenberg, PhD). This research was also supported by grant 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

References

- An J. S., Cooney T. M. (2006). Psychological well-being in mid to late life: The role of generativity development and parent-child relationships across the lifespan. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 410–421. 10.1177/0165025406071489 [Google Scholar]

- Bucx F., van Wel F., Knijn T. (2012). Life course status and exchanges of support between young adults and parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 101–115. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00883.x [Google Scholar]

- Burholt V., Wenger G. C. (1998). Differences over time in older peoples’ relationships with children and siblings. Ageing and Society, 18, 537–562. 10.1017/S0144686X98007090 [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Silverstein M. (2000). Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents in China. Research on Aging, 22, 43–65. 10.1177/0164027500221003 [Google Scholar]

- Cruza-Guet M., Spokane A. R., Caskie G. I. L., Brown S. C., Szapocznik J. (2008). The relationship between social support and psychological distress among Hispanic elders in Miami, Florida. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 427–441. 10.1037/a0013501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. R., Melisaratos N. (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595–605. :10.1017/S0033291700048017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efklides A., Kalaitzidou M., Chankin G. (2003). Subjective quality of life in old age in Greece: The effect of demographic factors, emotional state, and adaptation to aging. European Psychologist, 8, 178–191. :10.1027//1016-9040.8.3.178 [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen D. J. (1992). Family structure and intergenerational exchanges. Research on Aging, 14, 427–447. 10.1177/0164027592144001 [Google Scholar]

- Erickson E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2nd ed.). New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L., Miller L. M., Birditt K. S., Zarit S. H. (2009). Giving to the good and the needy: Parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71, 1220–1233. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00665.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried L. P., Carlson M. C., Freedman M., Frick K. D., Glass T. A., Hill J. … Zeger S. (2004). A social model for health promotion for an aging population: Initial evidence on the experience corps model. Journal of Urban Health, 81, 64–78. 10.1093/jurban/jth094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour M. M., Osypuk T. L. (2012). Promoting health and improving survival into very old age. British Medical Journal, 345, 6452. 10.1136/bmj.e6452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald T. L., Liao D. H., Seeman T. E. (2012). Contributing to others, contributing to oneself: Perceptions of generativity and health in later life. The Journals of Gerontology, 67, 660–665. 10.1093/geronb/gbs034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M., Tomas J. M., Galiana L., Sancho P., Cebria M. A. (2013). Predicting life satisfaction of the Angolan elderly: A structural model. Aging and Mental Health, 17, 94–101. 10.1080/13607863.2012.702731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartnett C. S., Furstenberg F. F., Fingerman K. L., Birditt K. S. (2012). Parental support during young adulthood: Why does support decline with age? Journal of Family Issues. 34. 10.1177/0192513X12454657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki T. K., Eisenberger N. I. (2012). Neural correlates of giving support to a loved one. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74, 3–7. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182359335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay D. W. K., Bergman K. (1966). Physical disability and mental health in old age: A follow-up of a random sample of elderly people seen at home. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 10, 3–12. 10.1016/0022-3999(66)90128-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes C. L. M. (2002). The exchange of emotional support with age and its relationship with emotional well-being by age. The Journals of Gerontology, 57B, P518–P525. 10.1093/geronb/57.6.P518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J., Krause N. M., Bennett J. M. (2001). Social exchange and well-being. Psychology and Aging, 16, 511–523. 10.1037/0882-7974.16.3.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.-W. (2004). Intergenerational interdependence: Mid-life couples’ help exchange in a three-generational model. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 32, 275–290. 10.1177/1077727X03261175 [Google Scholar]

- Littell R. C., Milliken G. A., Stroup W. W., Wolfinger R. D. (1996). SAS system for mixed models. Cary, NC: SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt M. W., Norris J. E., Hebblethwaite S., Arnold M. L. (2008). Intergenerational transmission of values: Family generativity and adolescents’ narratives of parenting and grandparent value teaching. Journal of Personality, 76, 171–198. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00483.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi A. S., Rossi P. H. (1990). Of human bonding: Parent-child relations across the life course. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason B. R., Sarason I. G., Pierce G. R. (1990). Traditional views of social support and their impact on assessment. In Sarason B. R., Sarason I. G., Pierce G. R. (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp. 9–25). New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M., Gans D., Yang F. M. (2006). Intergenerational support to aging parents: The role of norms and needs. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 1068–1084. 10.1177/0192513X06288120 [Google Scholar]

- Son J., Wilson J. (2011). Generativity and volunteering. Sociological Forum, 26, 644–667. 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2011.01266.x [Google Scholar]

- Strazdins L., Broom D. H. (2007). The mental health costs and benefits of giving social support. Intergenerational Journal of Stress Management, 14, 370–384. 10.1037/1072-5245.14.4.370 [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. A. (2010). Is it better to give or receive? Social support and the well being of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 65B, 351–357. 10.1093/geronb/gbp113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaux A. (1988). Social support: Theory, research, and intervention. New York: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Ward R. A. (2008). Multiple parent-adult child relations and well-being in middle and later life. The Journals of Gerontology, 63B, S239–S247. 10.1093/geronb/63.4.S239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner L. M., Schuz B., Wurm S., Ziegelmann J. P., Tesch-Romer C. (2010). Giving and taking: Differential effects of providing, receiving and anticipating emotional support on quality of life in adults with multiple illnesses. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 660––670. 10.1177/1359105310368186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler J. A., Gorey K. M., Greenblatt B. (1998). The beneficial effects of volunteering for older volunteers and the people they serve: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 47, 69–79. 10.2190/VUMP-XCMF-FQYU-V0JH [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubenko G. S., Marino L. J., Sweet R. A., Rifai A. H., Mulsant B. H., Pasternak R. E. (1997). Medical comorbidity in elderly psychiatric inpatients. Biological Psychiatry, 41, 724–736. 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00337-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]