Abstract

BACKGROUND

Alcohol brief intervention (BI) in primary care (PC) is effective, but remains underutilized in spite of multiple efforts to increase provider-initiated BI. An alternative approach to promote BI is to prompt patients to initiate alcohol-related discussions. Little is known about the role of patients in BI delivery.

OBJECTIVE

To determine the characteristics of PC patients who reported initiating BI with their providers, and to evaluate the association between initiator (patient vs. provider) and drinking following a BI.

METHODS

In the context of clinical trial, patients (N=267) who received BI during a PC visit reported on the manner in which the BI was initiated, readiness to change, demographics, and recent history of alcohol consumption. Drinking was assessed again at 6-months following the BI.

RESULTS

Fifty percent of patients receiving a BI reported initiating the discussion of drinking themselves. Compared with those who reported a provider-initiated discussion, self-initiators were significantly younger (43.7 vs. 47.1, p=.03), more likely to meet DSM criteria for current major depression (24% vs. 14%, p=.04), and more likely to report a history of alcohol withdrawal symptoms (68% vs. 52%, p<.01). Baseline readiness to change, baseline consumption rates, and current DSM-IV alcohol dependence were not different between groups. In the two-to-three weeks following BI, self-initiators reported greater decreases in drinks per week (5.7 vs. 2.4, p=.02), and drinking days per week (1.0 vs. 0.3, p=.002). At six month follow up, self-initiators showed significantly greater reductions in weekly drinking compared to those whose provider initiated the BI (p=.002).

CONCLUSIONS

Patient- and provider-initiated BI occurred with equal frequency, and patient-initiated BIs were associated with greater reductions in alcohol use. Future efforts to increase the BI rate in PC should include a focus on prompting patients to initiate alcohol-related discussions.

Keywords: primary care, brief intervention, physician-patient relations, alcohol consumption, patient activation, alcohol misuse, physician-patient communication

1. Introduction

There is ample evidence of the efficacy and effectiveness of alcohol screening and brief intervention (BI) in primary care (Bertholet et al., 2005; Kaner et al., 2007; O'Donnell et al., 2014), which prompted the 2013 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation that healthcare providers proactively screen their adult patients for alcohol misuse (Moyer, 2013). In spite of this evidence, numerous studies have documented the underutilization of BI, and many have attempted to address this problem by encouraging providers to do more screening and intervention as part of routine primary care (Aalto et al., 2003; Babor et al., 2005; Aspy et al., 2008; Onders et al., 2014). These studies have reported some success, particularly for large health systems such as the Veterans Administration (Lapham et al., 2012); however, the typical effect of these implementation efforts on provider BI rates is modest and short-lived (Beich et al., 2002; Babor et al., 2005; Nilsen et al., 2006; Rose et al., 2008).

The limited success of provider-targeted interventions to promote BI suggests that new approaches to increase BI uptake are needed. There is evidence that when a patient identifies a medical concern, it is more likely to be addressed and resolved than when it is identified by their health care clinician (Maly et al., 1999; Enguidanos et al., 2011). Thus, patients could be cued to raise concerns about their drinking themselves, for example with posters or brochures in the clinic waiting and exam rooms. It is not clear to what extent patients initiate BI in routine practice.

Information about what actually transpires during an office visit – either in an efficacy trial or in routine practice – can be ascertained using post-visit questionnaires or interviews of patients and providers. These interviews may include provider checklists of topics addressed during the visit or counseling modules completed (e.g., (Aalto et al., 2002; Aira et al., 2003, 2004); direct observation of sessions (Seppa et al., 2004; Makoul et al., 2006; McCormick et al., 2006; Bertakis & Azari, 2007; Gaume et al., 2008; Allamani et al., 2009), or review of records (e.g., Aira, 2004). Such studies consistently demonstrate that providers do not routinely ask about alcohol (e.g., Aalto et al., 2002), and rarely do so using standardized questionnaires (Seppa et al., 2004). They spend a small amount of time discussing alcohol (Bertakis & Azari, 2007), and are unlikely to complete all the counseling steps for BI (Seppa et al., 2004; McCormick et al., 2006; Chossis et al., 2007; Moriarty et al., 2012). Of most relevance to this study, direct observation research has documented cases in which patients disclose unhealthy alcohol use to the provider without prompting, but their disclosures are rarely followed up in a therapeutic manner by the provider (e.g., McCormick et al., 2006).

What these qualitative studies of BI delivery have not reported is the frequency with which the topic of unhealthy drinking, when raised, is initiated by the patient instead of by the provider. This paper presents secondary analyses of data obtained from patients who had received BI from their provider and subsequently enrolled in a 6-month randomized trial that evaluated the efficacy of alcohol self-monitoring using a 4-group design (Helzer et al., 2008). It poses three primary research questions: (1) How often do patients who received a BI and consented to participate in a trial report initiating a discussion of drinking with their provider vs. the provider initiating; (2) Are there characteristics, such as readiness to change, that differentiate self-initiators from patients whose providers initiated the BI, and (3) Is there an association between patient initiation of BI and change in alcohol drinking following the BI? Because these data were obtained only from those who had received BI as part of a research trial, they do not allow us to determine how often a patient in general practice brings up their drinking, asks for help, or how often such initiations result in BI. Neither participants nor providers could be randomly assigned to either initiate or not initiate the BI, so causality cannot be tested. However, examination of the sample in terms of who raised the topic of heavy drinking has implications for future effectiveness trials. Importantly, if we find evidence that patients do indeed raise the issue and we can characterize those patients, then we may be able to generate hypotheses about patient-focused prompts that might be developed and tested to activate patients to initiate BI.

2. Methods

2.1 Study Start-Up

As previously mentioned, the data presented in this manuscript were obtained in the context of a clinical trial that tested the efficacy of four different strategies for post-BI self-monitoring of alcohol consumption following a physician-delivered BI. Participants were followed for 6 months after they had received a BI from a primary care provider. In preparation for the trial, the research team conducted on-site training in the principles of BI to all clinic providers associated with the study (N=112), according to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism training manual (NIAAA, 1997). The four steps of a BI include: (1) ask about alcohol use; (2) assess for alcohol-related problems; (3) advise appropriate action (i.e., abstain or cut down), and (4) monitor patient progress. We distributed the accompanying brief intervention booklet “The Physicians’ Guide to Helping Patients with Alcohol Problems” (NIAAA, 1995).

During recruitment, we prominently displayed professionally-made posters in every waiting room and examination room that encouraged patients who were “concerned about (their) drinking” to discuss their concerns with the provider. Each poster had a pocket containing copies of the NIAAA patient education pamphlet, “How to Cut Down on your Drinking” (NIAAA, 1996). The goal of these posters was to: 1) encourage patients to raise concerns about their drinking with their providers, and 2) indicate that providers were open for such a discussion. Our logic was that patient initiation would contradict the common provider perception that patients would be offended by alcohol screening (CASA, 2000), and would convey to the provider that the patient welcomed such a discussion.

Throughout the trial, we undertook a number of methods to encourage, incentivize, and remind providers to conduct BI and refer patients to the study (Rose et al., 2010). Briefly, these strategies included the following: pre-recruitment workshops and individual BI trainings for providers; screening of patients for at risk drinking; on-chart notification to providers of patients who met at-risk drinking criteria; thank you notes to providers for each patient referred to the study; notification to providers when their referred patients enrolled in the study, and monthly feedback reports to providers and clinic staff at each site showing the number of referrals they had made to the study. Provider training “booster sessions” on BI were offered throughout the recruitment period.

2.2 Recruitment Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited from April, 2000 to July, 2003 from 15 clinics providing primary care in Chittenden County, VT (population ca. 150,000). Clinics specialized in primary care internal medicine (N=11), family practice (N=3), and gynecology (N=1). Most participating clinics (N=9) were affiliated with the university health care system; the remaining six were private clinics providing medical services to the same general community.

In the context of a routine office visit, primary care providers conducted BI with their patients when indicated according to their clinical judgment. With their patients’ permission, providers referred these patients to the study. Our research assistant contacted referred patients to obtain informed consent and schedule a baseline assessment at the research center. The assessments were scheduled as soon after the BI as the patient’s schedule allowed (mean = 18 days).

To be eligible, patients must have reported an average alcohol consumption in the 3-months preceding the BI that exceeded NIAAA recommended guidelines for low risk drinking. Participants were included if they exceeded the recommended maximums of 14 drinks per week for men and 7 per week for women, and/or exceeded 4 drinks per day (men) or 3 drinks per day (women) at least once in each of the past three months. Exclusion criteria for the study included: 1) current (past year) diagnosis of substance dependence other than alcohol, nicotine or marijuana based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (APA; 1994); 2) current DSM-IV diagnosis of any psychotic illness; 3) for patients taking antidepressant medication, any change in agent or dosage in the past 3 months; 4) plans to move out of the area within six months; or 5) lack of daily access to a telephone.

2.3 Study Design

Eligible patients were randomized to one of four treatment conditions: three experimental treatment arms involved calling an automated interactive voice response (IVR) telephone system daily to report alcohol use along with other variables such as mood and stress levels. One experimental group was assigned to daily IVR calls, a second group called the IVR daily and received monthly feedback about their drinking, and the third IVR group received feedback plus financial incentive for maintaining a daily call rate above 90%. The fourth group was a control condition in which participants were not assigned to the IVR. Participants returned to the research center for assessments at 3 and 6 months post-randomization. The IVR intervention and the full study procedures are detailed in Helzer et al. (2008). All procedures were approved by the University of Vermont Human Subjects Committee.

2.4 Overview and Timing of Assessments

Participants visited the research center on three occasions: a baseline assessment, and follow-up assessments at 3- and 6-months. The baseline assessment included diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV diagnoses and alcohol consumption, an evaluation of BI initiation, and readiness to change. The follow-up interviews assessed alcohol consumption in the past 90 days.

2.5 Measurements

2.5.1 Alcohol use

At each assessment, we administered the Timeline Followback (TLFB; Sobell et al., 1992). The TLFB has established reliability (Sobell et al., 1979; Sobell et al., 1986; Sobell et al., 1988) and validity compared to collateral reports and biological samples via breathalyzer (Polich, 1982; Maisto et al., 1985). The baseline TLFB asked subjects to report the number of standard drinks consumed on each of the preceding 90 days, which covered the time period before the BI (mean = 71 days), as well as the period between the BI and our baseline assessment (mean = 18 days). Although it is unconventional to use the TLFB to ascertain both pre-BI and post-BI drinking in a single administration, it was necessary in this case because referral to the study was not made until after the BI and there was no opportunity to ascertain pre-BI drinking before the BI occurred. Research assistants identified the date of the PCP visit as an anchor point during the TLFB administration.

The 3- and 6-month follow-up TLFB assessments covered the time period since the previous assessment, which was approximately 90 days. Data from the TLFB were used to construct our primary outcome variables: number of drinks per week, number of drinking days per week, and number of drinks per drinking day. Thus, outcomes at 3 and 6 months reflect the average drinking across the approximately 90 days prior to each assessment.

2.5.2 DSM-IV Diagnoses

The Composite International Diagnostic Interview- Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM) (Cottler et al., 1989) was administered to each potential participant at the baseline assessment after the TLFB administration to assess for Substance Use Disorders based on DSM-IV criteria (APA, 1994). The CIDI-SAM has been shown to provide reliable and valid diagnoses for adults and adolescents when administered by lay interviewers (Cottler et al., 1989). The major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and psychotic disorder sections of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (Robins et al., 1981) were administered to determine presence of major depression and psychotic disorders. The DIS has also been shown to have reliability and validity when administered by lay interviewers (Robins et al., 1982).

2.5.3 BI initiation

To minimize recall and social desirability bias, the assessment of who initiated the BI occurred within the context of the CIDI-SAM, which was administered after the TLFB. The following question was inserted into the alcohol section of the CIDI-SAM regarding occasions when the respondent talked to a doctor about drinking: “When you saw your provider, who initiated the conversation about drinking?” The available response options were: “patient” (i.e. self), “provider”, and “don’t know.”

2.5.4 Readiness to Change

At the baseline assessment we administered the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (RTCQ), a 12-item questionnaire based on Prochaska and DiClemente’s (1983) stages-of-change model, for assignment of harmful and hazardous drinkers to Precontemplation, Contemplation, and Action stages. Reliability and predictive validity of the instrument were demonstrated by Heather et al. (1993) and Rollnick et al. (1992).

2.5 Statistical Methods

Baseline comparisons between self- and provider-initiators on demographic and clinical characteristics were performed using t-tests for continuous measures and chi square tests for categorical variables. Repeated measures analyses of variance were used to examine changes in alcohol consumption outcomes across the two groups over time. The first set of repeated measures analyses compared changes in drinking from the pre-BI time period to the time between the BI and randomization (post-BI). The subsequent repeated measures analysis examined longer term outcome to 6-months in the subset of participants with available data (n=219). Because participants in the trial were randomized to one of four treatment conditions, treatment condition and its interaction with initiation group and assessment time were included in the model as additional factors. Additionally, chi square tests were used to compare the two initiation groups on the availability of longer term follow-up data, and to determine if the two initiation groups were appropriately balanced across treatment conditions. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software Version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was determined based on α=.05.

3. Results

3.1 Sample Characteristics

Participants were interviewed 18.4 ± 10.8 (mean ± SD) days after their brief intervention. At that baseline assessment, 130 subjects (47%) responded that their provider initiated the in-office discussion of alcohol use; 137 (50%) reported that they had brought up the subject of alcohol themselves, and 9 patients (3%) indicated that they did not know who initiated the BI. Subsequent analyses are limited to the 267 participants who reported knowing who initiated the discussion.

Demographic characteristics and baseline drinking data are presented in Table 1. At baseline, subjects reported they drank a mean of 29.3 ± 20.2 drinks per week and 5.3 ± 3.3 drinks per drinking day in the period prior to their BI. Seventy percent of the sample met criteria for current alcohol dependence on the baseline CIDI-SAM (administered post-BI).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Overall | Self Initiated |

Physician Initiated |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (n=267) | (n=137) | (n=130) | p-value |

| Age (years) | 45.3 ± 12.8 | 43.7 ± 12.0 | 47.1 ± 13.5 | .03 |

| Education (years) | 14.8 ± 2.7 | 14.9 ± 2.6 | 14.9 ± 2.8 | .78 |

| % Male | 62 | 60 | 64 | .50 |

| % Caucasian | 96 | 97 | 95 | .47 |

| % Married | 55 | 58 | 53 | .45 |

| % Employed full-time | 77 | 80 | 73 | .21 |

| % Ever depressed | 54 | 56 | 52 | .56 |

| % Currently depressed | 19 | 24 | 14 | .04 |

| Age of first regular alcohol use (years) | 19.4 ± 5.8 | 19.8 ± 6.3 | 18.9 ± 5.2 | .19 |

| % History of legal problems due to drinking | 35 | 38 | 32 | .33 |

| % Smoked cigarettes past 7 days | 31 | 34 | 28 | .32 |

| Number of drinks per week | 29.3 ± 20.2 | 29.6 ± 20.7 | 29.0 ± 0.2 | .83 |

| Number of drinking days per week | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 1.7 | .84 |

| Number of drinks per drinking day | 5.3 ± 3.3 | 5.4 ± 3.4 | 5.1 ± 2.8 | .35 |

| % Drinking within NIAAA guidelines | 8 | 6 | 10 | .21 |

| % Reporting withdrawal symptoms | 60 | 68 | 52 | <.01 |

| % Current DSM-IV Alcohol Dependence | 70 | 72 | 68 | .50 |

Note: Values represent mean ± SD, unless otherwise specified. Statistical significance is based on t-tests for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical variables (α = .05).

There were no significant differences between those who reported that the BI was self-initiated vs. provider-initiated on gender, years of education, race, employment status, or the percentage of subjects who reported legal problems associated with their alcohol consumption (Table 1). The two initiation groups also did not differ on the percentage with current alcohol dependence or any measures of pre-BI drinking (i.e. weekly consumption, number of drinking days, and drinks per drinking day). However, self-initiators were younger (43.7 vs. 47.1, t265 = 2.18, p=.03), more likely to report being currently depressed (24% vs. 14%, X21= 4.08, p=.04), and report alcohol withdrawal symptoms (68% vs. 52%, X21= 7.43, p < .01).

3.2 Readiness to Change

Provider- and self-initiators were similar on Readiness to Change (X22 = 1.8 p=.40), with the following distributions of patients in Precontemplation (self 26%, provider 24%), Contemplation (self 42%, provider 37%), and Action (self 31%, provider 39%) stages.

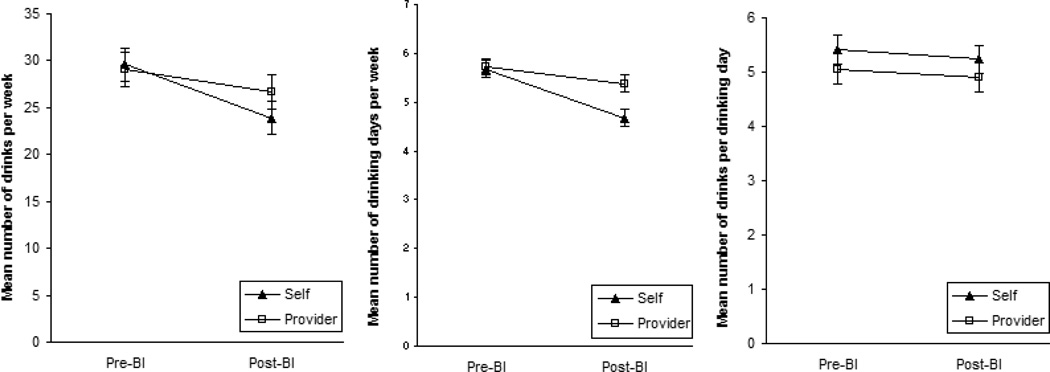

3.3 Consumption changes at initial Post BI assessment

Timeline follow-back reports were used to compare subjects’ consumption levels prior to their BI (71.4 ± 11.0 days) with levels reported for the days after their BI (18.4 ± 10.8 days), as assessed at baseline. Subjects who reported self-initiating had over twice as large a reduction on average than those who indicated that the provider initiated the BI (5.7 vs. 2.4 drinks per week; F1,265 = 5.5, p=.02; Figure 1). Self-initiators also experienced a significantly greater reduction in drinking days per week (1.00 vs. 0.34; F1,265 = 10.2, p=.002). The decrease in average number of drinks per drinking day was not dependent on who initiated the discussion (F1,251 = 0.1, p=.86).

Figure 1.

Comparisons of the self- versus provider-initiated groups on three measures of consumption prior to and two weeks following the brief intervention.

3.4 Six-Month Follow Up

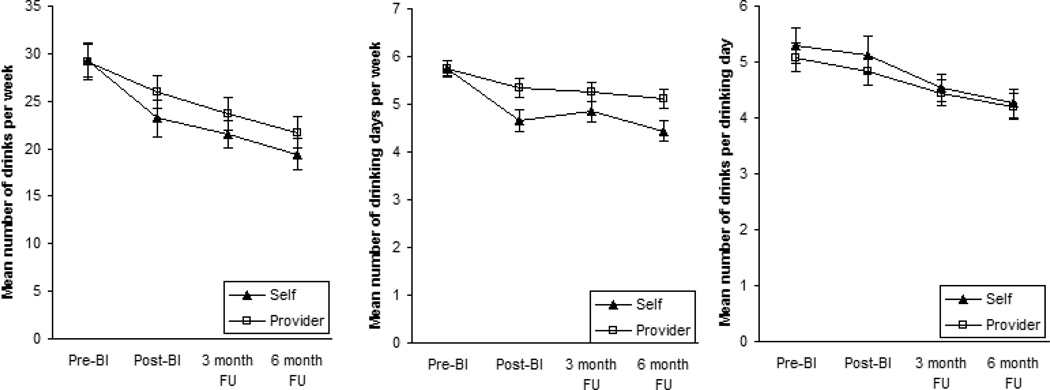

Most participants (82%, n=219) completed additional TLFBs scheduled for 3- and 6-months after their BI. The percent of subjects with available follow-up data did not differ across the two initiation groups (80%, n=110 for self-initiators and 84%, n=109 for provider-initiators, X21=0.6, p=.45). In addition, the two initation groups did not differ significantly with respect to the experimental conditions to which subjects were randomized (X23 = 4.13, p=.24). Furthermore, there was no evidence that differences in temporal changes between initiation groups were dependent on treatment condition (F9,632=0.96, p=.47; F9,632=1.15, p=.32; and F9,609=0.95, p=.48 for drinks per week, drinking days per week and drinks per drinking day, respectively).

There was no evidence that reductions observed in drinks per week out to six months after receiving the brief intervention were significantly different between the two initiation groups (F3,632=1.93, p =.12; Figure 2). By six months, participants who reported self-initiating reduced their weekly consumption by 4.4 drinks (18.8%) compared to 3.3 drinks per week (13.5%) for provider-initiators.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of the self- versus provider-initiated groups on three measures of consumption prior to and six months following the brief intervention.

However, in drinking days per week measured at the 6-month assessment, self-initiators continued to experience a significantly greater reduction compared to those with whom the provider had initiated the discussion (F3,632=5.1, p=.002). The mean decrease for self-initiators was 1.4 days (24%) compared to 0.6 days (10.3%) for provider-initiators. For number of drinks per drinking day, there was no evidence changes were dependent upon who initiated the discussion (F3,609=0.6, p=.58) with mean changes of 0.5 and 0.4 drinks per drinking day for self and provider initiators, respectively.

4. Discussion

Our findings have important implications in a number of areas. Primarily, they show that in the context of patient-directed cues in exam rooms and waiting rooms, patients often initiate conversations with their doctors about drinking. In other words, BI is not necessarily an exclusively provider-initiated process.

Secondly, our findings showed that patients who initiated the discussion were similar on most baseline characteristics to those who reported that their provider initiated, with a few exceptions. Self-initiators were younger and more likely to report symptoms of major depression and alcohol withdrawal (see Table 1). We suspect that patients with more clinical symptoms might have had greater impetus to seek relief, thereby taking initiative to seek advice. Regarding patient age, previous studies have shown a negative association between age and odds of receiving a BI (Bertakis & Azari, 2007; Kaner et al., 2001; Korthuis et al., 2008). Why BIs were more likely to be initiated by younger patients in our study is not known, but we can speculate that it may have to do with older patients tending to have more pressing physical health issues to discuss, and longer existing relationships with their physicians. Anecdotally, providers in our studies have shared 1) that they are reluctant to raise the topic of drinking with patients on the first visit (thereby leaving room for the patient to bring up the topic), and 2) that they may not prioritize behavioral health screening with established patients because they (often erroneously) assume that the patient’s alcohol consumption and other lifestyle habits had remained stable over time.

Thirdly, results showed short-term drinking outcomes were superior for self-initiated BIs compared with provider-initiated. This initial measurement of the BI effect occurred prior to randomization so it did not have the potential to be confounded by experimental condition. Self-initiators continued to show greater reductions in drinking frequency through 6 months, compared with provider-initiators.

Finally, our results illustrate the potential for a different approach to promoting BI in primary care settings. To date, efforts to trigger more BIs in the primary care setting have been directed toward providers. This study suggests that focusing attention on patient initiation, e.g., by using prominent patient directed posters, brochures, or other possible tools in examination and waiting rooms, may be as fruitful and deserves further study.

4.1 Limitations

The sample used in this study was highly selective and thus the generalizability of results my be limited. Specifically, the sample consisted of patients who not only received a BI from their provider, but were also referred to the trial by the provder and opted to enroll in the trial. We know that the BI and referral practices of the providers in this study were variable (Rose et al., 2010), and enrollment in a research trial often introduces selection bias (Taylor et al., 1982). We suspect that selection bias accounts for the large proportion (70%) of patients with alcohol dependence in this sample, in that patients with alcohol dependence in these clinics were more likely to have: a) been identified by their provider as needing intervention, b) been referred to the research study by their provider, and/or c) accepted the invitation to the trial. Thus, the results allow us to conclude that, among patients who received a BI from a provider, were referred to a research trial, and subsequently consented to participate in a trial, half reported having initiated the conversation about alcohol with their provider. Implications of the study for broader, more general populations of primary care patients are unclear, but we suspect that patients who accepted the study invitation and followed through with it may represent a motivated sub-sample of individuals. Thus, the rate of self-initiation among those who declined participation may have been lower than we observed in this sample.

This study classified patients into self- or provider-initiators based on patient self-report. While this assessment method has been used in other studies (e.g., Aalto et al., 2002), it introduces recall bias. A future study could increase validity by also asking providers their impressions of who initiated the discussion, or by videotaping patient encounters and making objective observations. Such methods would contribute to our understanding of how often patient-initiated BI occurs, by whom, and under what circumstances it results in provider intervention rather than a missed BI opportunity (McCormick et al., 2006; Moriarty et al., 2012).

Our use of a single TLFB administration to ascertain drinking during two distinct time periods is unconventional. This procedure was necessary because our baseline assessment occurred only after a BI and study referral by a provider. We recognize that responses could be biased based on social desirability; however, because the baseline assessment occurred prior to randomization, any bias would likely have been present with all participants and thus would not have distorted our findings regarding BI initiation. Furthermore, social desirability may have been offset by the fact that the baseline assessment was separated from the PCP visit by more than two weeks, thereby decoupling the interview from the BI itself. In order to minimize social desirability influences on patients’ reports of drinking based on who initiated the BI, we assessed baseline drinking first, then asked about initiation. However, this may have created a different kind of social desirability bias whereby those who had made the largest changes in their drinking may have been more likely to recall that they initiated even if their provider had been the one to do so.

4.2 Directions for Future Research

Future research is needed to more definitively determine the causes and effects of patient initiation. This report is based on post-hoc analysis of data from a trial that was not designed specifically to answer questions about BI self-initiation, and it remains unclear whether self-initiation per se affected the observed outcomes or whether some unmeasured factor influenced both the initiation and the behavior change. Furthermore, it is not known how or if the self-initiation may have influenced the quality of the BI.

Whether or not prompting patients to initiate BI would actually increase its efficacy in addition to its frequency is likewise unknown. Our use of examining-room posters to prompt patient BI self-initiation was designed to increase the frequency of BI; however we have no empirical evidence of the effect of such patient-focused materials. A future randomized controlled trial examining the rate of patient and provider initiation in rooms with posters vs. rooms without them would help clarify the clinical utility of the posters we used. A useful extension of our research could involve an exit questionnaire designed to ascertain how many heavy drinkers saw the poster, whether it prompted them to initiate, or whether they believed the prompt to self-initiate was moot; i.e., they would have raised the issue even without seeing the poster. A provider interview could elucidate how many of the providers had recognized the need and had planned to do BI even if the patient had not raised the issue. Finally, it may be worthwhile to focus on varying the content of the posters to determine whether certain designs would provoke more initiations. For example, posters could feature one or more of the following: NIAAA limits for healthy drinking, common health conditions associated with excessive consumption, advantages to low-risk drinking, or normative comparisons. Conversely, less detailed posters might prove to be more effective.

While not an aim of the study, we acknowledge that provider-level factors may have affected the results. Existing literature examining the association between provider factors (such as demographic characteristics, practice-related variables, and alcohol consumption) and their self-reported use of alcohol-related health promotion activities is small and of mixed quality, and has yielded mixed findings (Bakhshi & While, 2014). Across studies, provider variables tended to explain only small amounts of variance in provider BI (e.g., Aalto & Seppa, 2007). More research is needed in order to understand the possible influences of provider, patient, practice, and relationship factors on BI delivery at all, and BI initiation in particular. If such relationships exist, they could be leveraged to promote more frequent BI.

4.3 Conclusion

The underutilization of BI is widely acknowledged, but more sophisticated efforts to increase utilization such as provider training (Aalto et al., 2003), academic detailing (Richmond et al., 1998; Hansen et al., 1999; Funk et al., 2005), and office systems modifications (Saitz et al., 2000; Babor et al., 2005) have had mixed or inconclusive results. Primary care providers do not have sufficient time to offer the many forms of behavioral intervention that have been recommended (Yarnall et al., 2003) because they must clearly attend to the complaint(s) that occasioned the visit. Given average visit times of about 15 minutes, there may be only “one minute for prevention” in the typical office visit (Stange et al., 2002). However, if patients raise their own concerns about drinking, drinking should become a part of the problem list for that visit or may prompt a subsequent visit devoted to this issue. Patient initiation also may help overcome any provider uncertainty about the propriety of such discussion or patient receptivity to it.

This is the first study of its kind to consider the frequency and characteristics of patients initiating their own BI. Our results indicate that in the presence of cues and in the context of a clinical trial recruitment protocol, approximately half of the patients who received brief intervention from a primary care provider reported initiating that discussion. Furthermore, patient-initiated brief interventions yielded reductions in consumption comparable to provider-initiated encounters in the same study, and comparable to what has been reported in the existing BI literature.

According to the present findings, future efforts to increase the use of BI in primary care may more fruitfully target patients in addition to providers. This study identifies specific research questions that can be examined in a systematic manner using controlled methodological approaches to further develop implications of prompting patients to initiate BI.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants R01AA011954 and R01AA014270 to John E. Helzer and R01AA018658 to Gail L. Rose from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

References

- Aalto M, Pekuri P, Seppa K. Primary health care professionals' activity in intervening in patients' alcohol drinking during a 3-year brief intervention implementation project. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aalto M, Pekuri P, Seppa K. Primary health care professionals' activity in intervening in patients' alcohol drinking: A patient perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aalto M, Seppa K. Primary health care physicians' definitions on when to advise a patient about weekly and binge drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1321–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aira M, Kauhanen J, Larivaara P, Rautio P. Differences in brief interventions on excessive drinking and smoking by primary care physicians: Qualitative study. Prev Med. 2004;38:473–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aira M, Kauhanen J, Larivaara P, Rautio P. Factors influencing inquiry about patients' alcohol consumption by primary health care physicians: Qualitative semi-structured interview study. Fam Pract. 2003;20:270–275. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allamani A, Pili I, Cesario S, Centurioni A, Fusi G. Client/general medical practitioner interaction during brief intervention for hazardous drinkers: A pilot study. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:775–793. doi: 10.1080/10826080802483860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington D.C.: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Aspy CB, Mold JW, Thompson DM, et al. Integrating screening and interventions for unhealthy behaviors into primary care practices. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:S373–S380. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TE, Higgins-Biddle J, Dauser D, Higgins P, Burleson JA. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in primary care settings: Implementation models and predictors. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:361–368. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhshi S, While AE. Health professionals' alcohol-related professional practices and the relationship between their personal alcohol attitudes and behavior and professional practices: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2014;11:218–248. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110100218. doi: DOI 10.3390/ijerph110100218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beich A, Gannik D, Malterud K. Screening and brief intervention for excessive alcohol use: Qualitative interview study of the experiences of general practitioners. British Medical Journal. 2002;325:870–872B. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7369.870. doi: DOI 10.1136/bmj.325.7369.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient gender and physician practice style. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:859–868. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, Burnand B. Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:986–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.9.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASA. Missed opportunity: Casa national survey of primary care physicians and patients on substance abuse. New York: Columbia University; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chossis I, Lane C, Gache P, et al. Effect of training on primary care residents' performance in brief alcohol intervention: A randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1144–1149. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0240-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The reliability of the cidi-sam: A comprehensive substance abuse interview. Br J Addict. 1989;84:801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enguidanos S, Coulourides Kogan A, Keefe B, Geron SM, Katz L. Patient-centered approach to building problem solving skills among older primary care patients: Problems identified and resolved. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2011;54:276–291. doi: 10.1080/01634372.2011.552939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk M, Wutzke S, Kaner E, et al. A multicountry controlled trial of strategies to promote dissemination and implementation of brief alcohol intervention in primary health care: Findings of a world health organization collaborative study. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:379–388. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Daeppen JB. Brief alcohol interventions: Do counsellors' and patients' communication characteristics predict change? Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:62–69. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen LJ, Olivarius N, Beich A, Barfod S. Encouraging gps to undertake screening and a brief intervention in order to reduce problem drinking: A randomized controlled trial. Fam Pract. 1999;16:551–557. doi: 10.1093/fampra/16.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Rollnick S, Bell A. Predictive validity of the readiness to change questionnaire. Addiction. 1993;88:1667–1677. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Rose GL, Badger GJ, et al. Using interactive voice response to enhance brief alcohol intervention in primary care settings. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:251–258. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD004148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004148.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaner EFS, Heather N, Brodie J, Lock CA, McAvoy BR. Patient and practitioner characteristics predict brief alcohol intervention in primary care. British Journal of General Practice. 2001;51:822–827. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis PT, Josephs JS, Fleishman JA, et al. Substance abuse treatment in human immunodeficiency virus: The role of patient-provider discussions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapham GT, Achtmeyer CE, Williams EC, Hawkins EJ, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA. Increased documented brief alcohol interventions with a performance measure and electronic decision support. Med Care. 2012;50:179–187. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Sanders B. Effects of outpatient treatment for problem drinkers. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1985;11:131–149. doi: 10.3109/00952998509016855. doi: Doi 10.3109/00952998509016855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoul G, Dhurandhar A, Goel MS, Scholtens D, Rubin AS. Communication about behavioral health risks: A study of videotaped encounters in 2 internal medicine practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:698–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maly RC, Bourque LB, Engelhardt RF. A randomized controlled trial of facilitating information giving to patients with chronic medical conditions - effects on outcomes of care. Journal of Family Practice. 1999;48:356–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick KA, Cochran NE, Back AL, Merrill JO, Williams EC, Bradley KA. How primary care providers talk to patients about alcohol: A qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:966–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty HJ, Stubbe MH, Chen L, et al. Challenges to alcohol and other drug discussions in the general practice consultation. Fam Pract. 2012;29:213–222. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer VA. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. How to cut down on your drinking. Washington, D.C.: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. The physicians' guide to helping patients with alcohol problems. Washington, D.C.: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- NIAAA. Training physicians in techniques for alcohol screening and brief intervention. Washington, D.C.: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P, Aalto M, Bendtsen P, Seppa K. Effectiveness of strategies to implement brief alcohol intervention in primary healthcare - a systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care. 2006;24:5–15. doi: 10.1080/02813430500475282. doi: Doi 10.1080/02813430500475282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell A, Anderson P, Newbury-Birch D, et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: A systematic review of reviews. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49:66–78. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onders R, Spillane J, Reilley B, Leston J. Use of electronic clinical reminders to increase preventive screenings in a primary care setting: Blueprint from a successful process in kodiak, alaska. J Prim Care Community Health. 2014;5:50–54. doi: 10.1177/2150131913496116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polich JM. The validity of self-reports in alcoholism research. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:123–132. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90037-5. doi: Doi 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Diclemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking - toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. doi: Doi 10.1037/0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond RL, K GN, Kehoe L, Calfas G, Mendelsohn CP, Wodak A. Effect of training on general practitioners' use of a brief intervention for excessive drinkers. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22:206–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National-institute-of-mental-health diagnostic interview schedule - its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Ratcliff KS, Seyfried W. Validity of the diagnostic interview schedule, .2. Dsm-iii diagnoses. Psychological Medicine. 1982;12:855–870. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700049151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold R, Hall W. Development of a short 'readiness to change' questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. Br J Addict. 1992;87:743–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose GL, Plante DA, Thomas CS, Denton LJ, Helzer JE. Utility of prompting physicians for brief alcohol consumption intervention. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:936–950. doi: 10.3109/10826080903534434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose HL, Miller PM, Nemeth LS, et al. Alcohol screening and brief counseling in a primary care hypertensive population: A quality improvement intervention. Addiction. 2008;103:1271–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R, Sullivan LM, Samet JH. Training community-based clinicians in screening and brief intervention for substance abuse problems: Translating evidence into practice. Subst Abus. 2000;21:21–31. doi: 10.1080/08897070009511415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppa K, Aalto M, Raevaara L, Perakyla A. A brief intervention for risky drinking--analysis of videotaped consultations in primary health care. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2004;23:167–170. doi: 10.1080/09595230410001704145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Cooper AM. Reliability of alcohol abusers self-reports of drinking behavior. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1979;17:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. doi: Doi 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method - assessing normal drinkers reports of recent drinking and a comparative-evaluation across several populations. British Journal of Addiction. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Toneatto T, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Johnson L. Alcohol abusers perceptions of the accuracy of their self-reports of drinking - implications for treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1992;17:507–511. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90011-j. doi: Doi 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90011-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Klajner F, Pavan D, Basian E. The reliability of a timeline method for assessing normal drinker college-students recent drinking history - utility for alcohol research. Addictive Behaviors. 1986;11:149–161. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90040-7. doi: Doi 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange KC, Woolf SH, Gjeltema K. One minute for prevention: The power of leveraging to fulfill the promise of health behavior counseling. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:320–323. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WC, Obitz FW, Reich JW. Experimental bias resulting from using volunteers in alcoholism research. J Stud Alcohol. 1982;43:240–251. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: Is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]