Abstract

Objectives

This study examined the family experience of critical care after pediatric traumatic brain injury in order to develop a model of specific factors associated with family-centered care.

Design

Qualitative methods with semi-structured interviews were utilized.

Setting

Two level 1 trauma centers.

Participants

Fifteen mothers of children who had an acute hospital stay after TBI within the last 5 years were interviewed about their experience of critical care and discharge planning. Participants who were primarily English, Spanish or Cantonese speaking were included.

Interventions

None

Measurements and Main Results

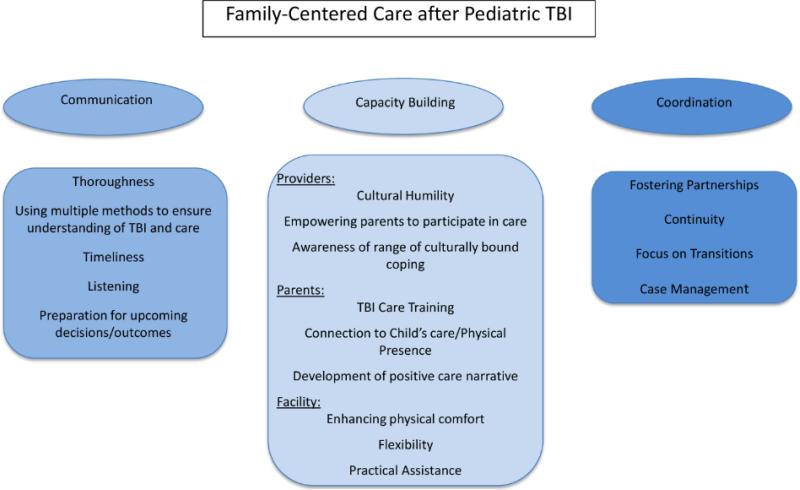

Content analysis was used to code the transcribed interviews and develop the family-centered care model. Three major themes emerged: 1) thorough, timely, compassionate communication, 2) capacity building for families, providers and facilities, and 3) coordination of care transitions. Participants reported valuing detailed, frequent communication that set realistic expectations and prepared them for decision-making and outcomes. Areas for capacity building included strategies to increase provider cultural humility, parent participation in care and institutional flexibility. Coordinated care transitions, including continuity of information and maintenance of partnerships with families and care teams were highlighted. Participants who were not primarily English speaking reported particular difficulty with communication, cultural understanding and coordinated transitions.

Conclusions

This study presents a family-centered traumatic brain injury care model based on family perspectives. In addition to communication and coordination strategies, the model offers methods to address cultural and structural barriers to meeting the needs of non-English speaking families. Given the stress experienced by families of children with TBI, careful consideration of the model themes identified here may assist in improving overall quality of care to families of hospitalized children with traumatic brain injury.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, family-centered care, pediatrics, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Previous studies have linked patient and family-centered care (FCC) to improved patient outcomes (1-4), family satisfaction (5) and staff satisfaction (6). Components of FCC include shared decision making and collaboration with family, assessing family coping, building on family strengths, consistent and honest communication, cultural and spiritual support, open visitation, confidentiality, presence of family at resuscitation and rounds and palliative care as appropriate (7-9). Despite recommendations for use of FCC by the Institute of Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Critical Care Medicine among others, institutions and providers struggle to implement the principles, leaving families feeling marginalized from care (10). Racial/ethnic and language disparities have been documented in FCC delivery for children with special health care needs (11). Conflicts between providers and families are pervasive in medical settings (12, 13) and impact FCC (13). Difficulties with use of FCC may be in part due to the general nature of the guidelines. Therefore, identifying specific FCC practices tailored to different patient and family populations may be an important step towards better integration and adaptation of the guidelines to family needs. Previous studies have identified family needs and coping after TBI (14-16). However, specific factors associated with quality FCC in the acute care setting for diverse families of children with traumatic brain injury (TBI) have not been identified.

This study explored the family experience of critical care after pediatric TBI in order to identify specific factors and barriers associated with high quality, FCC unique to this population and to develop a model of FCC specifically for families of children hospitalized with TBI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting and Participants

We recruited participants from two level 1 trauma center hospitals; one participant received initial care at a third level 1 trauma center and received follow up care at one of the recruiting sites. Each hospital had some general FCC policies in place, including inclusion of family in decision-making and presence of family at resuscitation. Purposive sampling was used (17). Potential participants from one site were identified through the Brain Injury Alliance of Washington and from the outpatient pediatric TBI clinic at the hospital. They were then approached by a research coordinator about possible interest in the study. Potential participants from the second site were identified from the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit database and contacted by a research coordinator about possible interest in the study. Participants were mothers of children <18 years old who had an acute hospital stay for treatment of TBI within the last 5 years. At each of the sites, mothers of patients were consistently the primary caregivers to the injured child and were available for the interviews. The mothers interviewed had ample interactions with hospital staff and were well positioned to speak about the hospital stay and subsequent care of the child.

We aimed to include families from different racial/ethnic backgrounds as well as families with different primary language preferences. The study was reviewed by the University of Washington Human Subject Division and found to be exempt. The Institutional Review Boards at the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-University of California Medical Center reviewed and approved the study.

Interviews

An in-depth interview guide was created using a multi-step process (18). First, a literature review was conducted to identify initial concepts of interest and areas of inquiry. Next, one investigator (GR) interviewed acute care staff at one recruiting site to assist in prioritization of areas of inquiry and to identify additional areas of interest based on their experiences. Finally, the investigator team met as a group to discuss and prioritize the areas of inquiry based on the report from the staff interviews, the literature review and their own experiences. We aimed to include questions that provided participants the opportunity to speak about both positive and potentially negative experiences. Towards this aim, we included some targeted questions about topics the providers and investigator team thought were relevant as well as open-ended questions that allowed for story telling and elaboration from participants. After the first two interviews were completed, the guide was revised for clarity and conciseness. The final interview guide explored 6 main topics (see Table 1 for a select sample of questions): 1) overall quality of care, 2) impressions of treatment team, 3) communication, 4) coping, 5) discharge planning and transition home, and 6) rehabilitation.

Table 1.

Interview guide sample questions

| Topic | Sample interview questions |

|---|---|

| Quality of care | Tell me about the healthcare your child received. Do you feel there were ever significant delays in the delivery of your child's care? |

| Impressions of treatment team | What did your child's treatment team do well? What could be improved? |

| Communication | Tell me about a time when your child's doctors gave you information about your child's condition. What was that like? Was there anything you disliked or found frustrating about your communications with your child's healthcare team? |

| Coping | Tell me what it was like for you, as a parent, to be with your child in the hospital. What were some coping strategies you used during your child's hospital stay? |

| Discharge planning/transition home | How did the transition home go for you? Was there anything that surprised you? Is there any specific information or training that would have been useful to you before your child was discharged from the hospital? |

| Rehabilitation | Has your child received regular follow-up care since he/she was discharged from the hospital? |

A pre-screening call was completed with each participant approximately 24-72 hours prior to the interview in order to prompt reflection on the acute care period and allow the establishment of a relationship with the participant prior to formal interview. Five basic questions were asked about family composition and events surrounding their child's TBI and initial care. Each interview was then conducted by one investigator (MM) with the assistance of two other investigators (GR and AR) for some interviews. AR provided interpretation services for the Spanish-speaking participants. Phone interpretation was used for the Cantonese-speaking participant. Individual interviews were conducted with the majority of participants either in person, by phone or using videoconferencing and lasted between approximately 35 and 70 minutes. One focus group was conducted with three participants to accommodate schedules and lasted approximately 2.5 hours. An interpreter (AR) was utilized for the focus group. Because of the starting and stopping of dialogue required when using an interpreter, the format and participation in the focus group was similar to that of the individual interviews. Each participant answered the interview questions in turn and participants did not interact significantly or build upon each other's responses. Therefore, we coded and analyzed the focus group data in the same manner as the individual interviews. All interviews were transcribed verbatim with identifying information removed.

Analysis

Content analysis was the primary analytic approach used in this study (19). Researchers used inductive category development and deductive category application for creating the proposed model (19-20). Two investigators (MM and GR) read and coded the first four interviews to develop the data-driven initial codebook. Basic codes were identified and then categorized and defined within the 6 a priori defined topics of inquiry. Then, codes were sorted by the investigator team into content categories and themes. The team met and agreed upon categories and themes that were included in the codebook. Subsequent interviews were coded using the codebook, and as new codes arose they were added to the codebook through an iterative process of inter-coder reliability checking (21). After completion of all coding, broader themes were identified through counting the occurrences of each code and the number of participants that referred to the concept in the code. Expert knowledge from the interdisciplinary team was considered in interpreting codes and emerging themes. Data saturation was achieved when no new codes or categories emerged from the interviews; at this point it was determined that the sample size of 15 participants was sufficient (22). Subsequently, a preliminary model of FCC was developed. Finally, all interviews and codes were reviewed together and the model was agreed upon by investigator group (19). Model themes are described and illustrative quotes provided.

RESULTS

Family and Patient Characteristics

All of the participants were mothers of children who were treated in the acute care setting for TBI. At interview, the median time since injury was 8 months (range <1month to 40 months). Twelve (80%) children had Medicaid/CCS insurance for their child; 3 (20%) had private insurance. Eight (53%) participants identified as Hispanic, were primarily Spanish speaking and required an interpreter for interviews; 1 (7%) participant identified as Asian, was primarily Cantonese speaking and required an interpreter for the interview. These families were considered to have limited English proficiency (LEP). Three (20%) participants identified as Black or African American; 1 (7%) identified as White; 2 (13%) identified as multiracial. The median age at time of injury of the child with TBI was 8 years old (range 8 months-17 years). Median hospital length of stay was 4 days (range 1-105 days). In terms of injury severity, 20% were in severe TBI range based on ICU admission GCS <8, 20% were in moderate TBI range (GCS 9-12) and 60% were in mild TBI range. ICU median length of stay was 2 days (range 1-26). 40% were intubated, 20% had intracranial pressure monitoring and 13% had a gastrostomy procedure. All children of the participants survived the TBI. All of the children were injured accidentally. Three of the families mentioned involvement with child protective services related to the injury, but none of the injuries were intentional and all of the children were living at home with the parent at time of interview. Seven of the parents reported their child was doing well at home, and the remainder of the parents reported some ongoing needs, deficits or slow recovery. All of the parents reported spending ample time at the bedside during their child's hospital stay; each had sufficient opportunity to interact and communicate with staff.

Themes

Through expressions of both positive and negative experiences, key themes associated with perceived FCC were identified. These themes were 1) effective communication, 2) capacity building for families and providers, and 3) coordination of care. Several factors within each theme illuminate the specific characteristics or activities associated with a positive family experience of care. A model of all the themes and factors identified in this study is presented in Figure 1.

Fig 1.

Family-Centered Care Model for Critical Care after Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Theme 1: Effective Communication

Five factors were associated with effective communication in acute care settings: 1) thoroughness, 2) the use of multiple methods to ensure understanding of TBI and patient care, 3) timeliness, 4) listening, and 5) preparation for decisions and outcomes. These factors are discussed in detail below. When families spoke about communication, they referred to direct conversations, indirect communication, witnessed communication between providers and nonverbal communication. Participant quotes highlighting these factors are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effective communication techniques: select themes and illustrative quotes

| Effective communication techniques | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Thoroughness | [translated from Spanish] “...Well, they were saying almost everything. If they were gonna...do something they would always tell me what were they gonna do, how it was gonna happen...they would always tell me everything...it was good because they would say everything they were gonna do for my baby.” |

| Use of multiple methods to ensure understanding | “...the surgeon...he was my favorite person because he knew what he needed to do to save my son but he wasn't my favorite person of explaining things, only because he – it was like there was no middle ground like he either dumbed it down really, really, really, really like...you're dumb...you don't understand anything or he was talking in...medical terms.” |

| Timeliness | “Yeah, we were just kind of waiting. Not really sure when that person [the doctor] would arrive...we had no idea when we were gonna see anyone and we actually didn't know if we would see a doctor that night ...that was probably the toughest thing, was just waiting and waiting and waiting and not knowing when we would see [the doctor].” |

| Listening | “...[the doctor was] just so calm...his voice was just very calm...he wasn't rushing, he wasn't talking really quickly...[he answered] every question, even if we felt like it was dumb...[he was] giving us the time of day and not...ever treating us like we were-just another number.” |

| Preparation for decisions and outcomes | “...my son was not normal. They had told me from the time that we entered the hospital and the trauma team, from the time that we left that he would be fully normal and that in six weeks, he could go back to swimming. He could go back to, you know, as soon as that bone healed, that he would be a normal kid again. He would be his normal self.” |

Thorough communication

Parents were interested in hearing details about their child's injury and care plan. Overwhelmingly, parents expressed a desire for frequent communication and updates. Frequent updates served the purpose of involving families in their child's care plan, decreasing anxiety about procedures and prognosis and also signaled to parents that staff were attentive and aware of their child's needs.

Use of multiple methods to ensure understanding of TBI and care

Ensuring understanding by using multiple methods of communication emerged as an important construct from the stories families told about times when this was done and times when they were left without a clear understanding of their child's care or expected outcome. Families who were not primarily English speaking, who had LEP, were particularly disadvantaged in this area because professional interpreters were not always used and written information was not always translated.

Timeliness

Timing of care or communication was a theme in all of the interviews. Parents expressed a desire for frequent updates and timely communication when there was a status change or new critical information.

Listening

Participants expressed a desire to be listened to by providers. Many parents wanted support from staff and a sense that the providers cared about their child. The positive communication experiences were times when providers took time to engage with families and demonstrate empathy and respect for the family's experience.

Preparation for decisions and outcomes

Orienting families to what to expect in the care setting and beyond was very important to participants. Some families expressed that preparation for outcomes decreased anxiety and distress.

Theme 2: Capacity Building

Key focus areas to begin strengthening or building capacity were identified. Participants highlighted areas to consider capacity building within providers and parents and for the facility. Specific capacity building recommendations and illustrative quotes are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Capacity building: select themes and illustrative quotes

| Capacity building | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Providers | |

| Cultural humility | When asked about what was done to explain things about her child's condition, a parent with LEP said, [translated from Spanish] “They gave [me] some handouts that explained what was-what she had... No [the form was not translated]...the paper was in English but [my] dad is the one who knows more English and he's the one who understood it.” |

| Parent with LEP at end of research interview for this study: [translated from Spanish] “When there's a hematoma and a hemorrhage, what are the consequences in the future?” | |

| Family with LEP was asked to consent to incorrect surgical procedure on child's leg; family was concerned because they had not been previously told about a leg injury. Instead of dialogue and explanation about the procedure and potential error, the family was required to investigate the error. [translated from Spanish] “So [we]walked in...to the room...[we] were asking our daughter: ‘Can you please move your...leg? Lift ‘em up, move them, just to make sure that she was-that there was no problems with her legs...[I] would have liked somebody to go and apologize and explain it a little bit more. But the way [I] see it is that the doctors are just there to do what they're supposed to do. Like, for example, the doctors...they're just there to go do the surgeries. Not for anything else...” | |

| English speaking parent describing her experience with the treatment team: “I wouldn't change a thing. They communicated with me very openly, very honestly. Um, I know that sometimes doctors don't wanna get, um, too involved on a personal level. But they comforted me, and I could feel the sympathy and the empathy from them throughout the whole experience. Um, it was educational, as well. They didn't just say: ‘This is-, well, what we're gonna do.’ They explained why; they explained the pros and cons; they explained what the outcome could be, would be or should be. They explained – they just kept me informed every step of the way.” | |

| Another English-speaking parent describing communication with her child's doctor: “You know...he was walking in like a friend and he was like: ‘Hey, you guys, I know you've been having a really long day...and I just-I just want you guys to know...we've been looking all over her charts’-and-[he]...very thoroughly went through what they each had done...just totally...answering every question, even if we felt like it was dumb...he even said...’You're not bad parents...You know, this happens.” | |

| Empowering parents to participate in care | “...I didn't realize that they were actually expecting me to do the [diaper] changing while I was in the room...I didn't mind doing it but I didn't know.” |

| Awareness of culturally bound coping | “...having family be there to support [you] and we have a big family...I'm [an] extremely spiritual individual and so I prayed a lot...but also just having the ability to ask questions and know specifically what's going on with your child and what the next step is very important.” |

| Parents | |

| TBI care training | “They came and trained me and other family members [on tube feedings]...I was really uncomfortable with changing her shirt because of her bone being out...So the therapist came in and helped me get comfortable doing that...and they told me...that touching it wouldn't hurt...” |

| Connection to child's care | “...we were separated...I expected us to be reunited in the ER after he was stabilized...but there's only one parent allowed and me and my husband just kept thinking that what if something would have happened to him, and we were both separated. Like both of us should have been able to be there the whole time...” |

| Facility | |

| Enhancing physical comfort | “And I was sleepin’ all bundled in a little chair on the side of her for like a week. I didn't even never go home.” |

| Flexibility | [translated from Spanish]...[I felt] kind of sad because they [the family] all wanted to be there at the same time. But there was one time that a nurse, she was a good nurse, because she let [my] sisters and nieces be there with [the patient]...it was a little bit frustrating.” |

| Practical assistance | “Having to pay for parking every day and knowing how long families are there for, I thought it was crazy...I just thought that that whole parking thing added more stress.” |

Providers

Cultural humility is a concept taken from medical education paradigms and has been defined as “a process that requires humility in how physicians bring into check the power imbalances that exist in the dynamics of physician-patient communication by using patient-focused interviewing and care (23).” In our study, we identified this as a key strategy for provider capacity building based on differences in frequency and type of communication and overall quality care that were noted between English-speaking families and families with LEP. For example, some families with LEP reported receiving information they could not understand due to language barriers. Some also discussed not being told directly about their child's condition, but rather having information given to other family members and then relayed to them via that family member. There were also language-related issues with consent processes, with one family being asked to consent to the wrong procedure and another being told she had no choice but to consent to a procedure. None of the English-speaking families mentioned problems or issues related to consent procedures. Some of the differences noted were more subtle but equally important. For instance, several English-speaking families reported feeling empathy and compassion from the providers; none of the families with LEP reported this. This does not necessarily mean providers felt less empathy for families with LEP, but likely it was not communicated in a way that families were able to interpret. While parents with LEP were equally confident as the English-speaking parents that they had received detailed information about their child's injury, they were generally less able to describe details of medical information given to them and expressed limited understanding of residual sequelae from their child's injury. See example quotes in Table 4 that demonstrate the contrast between the English-speaking families’ experiences and the experiences of the families with LEP.

Table 4.

Coordination: select themes and illustrative quotes

| Coordination | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Fostering partnerships | “I think it would have been nice. As a parent, I think I would have felt better if the person releasing him would have been the same person who did the surgery. Not just some person who came in and had never seen him [the patient] before...” |

| Continuity | “...they [the medical team] came in and we had a little meeting and they made it seem like everything was going’ good...It was, but then the surgeon comes in like half hour later and gives us bad news. But the bad news was from the day before...then...[another doctor] came to apologize to us and he said that he actually did feel a little bit hopeful...it was after that that we made a complaint.” |

| Focus on Transitions | “I'm not sure I really knew what to expect...You don't know what's going to happen with them or how they're going to progress. But also, as a teenager, he was...15 at the time. There was a big transition with his emotional and mental state of mind. It's like for the fact that he was missing out with friends. He was missing out at school. He was stuck at home. He...went through a lot of depression so we had to get him counseling. So that was a little unexpected.” |

| Case Management | “I really feel like the care coordinators really tried to help you in every avenue that they could. They had a social worker there. They had a counselor there. They had a school teacher...the traumatic brain injury association [case manager] was very helpful as well. That was essential to be honest with you, having them there to help get him back into school and to communicate with the counselor and the teachers was essential because we were unaware of what we would be up against...” |

Tied to the concept of cultural humility is the need for increasing awareness of the scope of culturally bound coping. Coping is inherently intertwined with culture. While there were similarities in the strategies families used to cope, there were also differences. Parents expressed a sense of shock and a sense of feeling overwhelmed that required extra sensitivity, extra explanations and extra care for their well-being. Families with LEP have the additional challenge of being unable to understand communication directly from providers. Some parents reported utilizing family support and wanting family at the hospital with them. Other parents spoke about the importance of their spiritual faith as a coping strategy. Some English-speaking parents talked about the importance of asking questions and receiving updates about their child's care as a coping strategy, further highlighting the need to enhance the communication experience for families with LEP. All of the parents wanted to be physically near their child during the hospital stay.

Parents universally described the importance of participating in their child's care. However, parents were unsure about how to do this or when it might be appropriate, demonstrating the need for clinicians to assist and empower parents to participate in care.

Parents

In terms of capacity building for parents, participants expressed a desire for TBI-specific care training and being physically connected to their child's care. Parents describe confusion about how to appropriately care for their child at times, which extended from hospital to home.

Facility

Parents expressed discomfort in the setting related to limited space for sleeping and limited space for family. Enhancing the physical comfort of the environment was a key area for facility capacity building. Parents also expressed a desire for flexibility around hospital rules regulating time spent in child's room. Finally, families had financial hardships and practical difficulties managing their child's time in the acute care setting.

Theme 3: Coordination

The final domain associated with quality FCC was coordination. Families identified four factors related to coordination: fostering partnerships, continuity of care, focus on transitions and case management. Coordination factors and associated quotes from parents are presented in Table 4.

Fostering partnerships

The importance of partnerships between the family and team and also between the various care teams working with the family was highlighted. Families desired a sense of congruity between themselves and between the many care teams.

Continuity

Parents desired continuity of information being provided to them by different team members and providers from the various care teams assisting their child as well as continuity between teams and units in the hospital. When this wasn't done, it was extremely difficult for family members and trust in the team was lost.

Transitions

A focus on transitions was especially salient in the participant interviews. The transitions from the acute care setting to rehabilitation to home posed challenges for parents whether their child was doing extremely well or had significant rehabilitation challenges. If the child was well, some parents found it difficult to allow the child to return to their normal activities for fear of re-injury. If the child was struggling to regain skills, the emotional challenge of watching the recovery was noted.

Case management

Families reported difficulty with coordinating appointments, figuring out various insurance qualifications for different providers and difficulty transitioning back to school and sometimes work.

DISCUSSION

In this study, three major themes associated with high quality, FCC for families of children with TBI were identified: 1) thorough, timely and compassionate communication, 2) capacity building for families and providers, and 3) coordination of care transitions. Our findings align with other non-TBI specific research on provider-family interactions in the acute care setting (7-9) and with other studies that identified family needs and coping strategies after TBI (14-16). The model of FCC in critical care developed here adds new and specific insights into three major themes that are particularly salient for diverse families of children with TBI. Innovative ways to implement and test this model, such as using web-based prompts to staff, should be explored further in future studies (24).

Previous studies have reported the importance of communication in the ICU setting for family mental health (25) and for assisting family members to increase their knowledge of patients’ condition (26). In this study, parents reported valuing detailed, frequent and understandable communication that set realistic expectations and prepared them for decision-making and outcomes. The use of multiple communication methods was highlighted as an important strategy to improve communication. Despite the busy trauma center environment, our data suggest that listening to families’ questions as well as communicating that each patient is a unique individual are key provider behaviors that can lead to a positive family experience. In particular for families with LEP, use of professional interpreters, translated material and incorporating ways to provide them with the same frequency of updates as English-speaking families are warranted. This can be particularly challenging for providers who do not speak the families’ primary language because it takes extra time to find an interpreter. Quick consults or updates given to English speaking families in between trips to the operating room or done quickly before the end of the shift are often not provided to families with LEP. The differences in communication to English-speaking families versus families with LEP noted in this study call for a serious examination of how barriers to communication can be overcome to reduce disparities in health care provision to children with TBI.

Recommendations from previous studies to address racial/ethnic and language disparities in FCC included increasing provider time with families and using a team approach (11) as well as an explicit focus on meeting the language needs of families with LEP (27). In the present study, areas identified for capacity building included methods to increase provider cultural humility, parent participation in care and institutional flexibility. Increasing cultural humility and incorporating this into practice may be beneficial for improving provider-patient interactions and overall patient care. Maintaining an open and non-judgmental stance to the variety of coping strategies in use emerged as a critical piece of quality care for families. For example, the extra sensitivity requested by families may be particularly important for families with LEP who are dealing not only with the traumatic experience of an injured child in the acute care setting but with the additional challenge of having difficulty understanding communication from providers.

Empowering parents with knowledge and skills to participate in care was another important aspect of FCC identified. Parents universally identified participation in their child's care as a salient area for capacity building. The complicated care required after TBI requires special training and attention from staff. With regard to facility capacity building, data suggested that rules should be clearly explained to families so that they understand the rationale, and then when appropriate, flexibility is warranted given the stressful nature of the acute care experience. In addition, interviews suggested that assistance with parking, food vouchers, financial aid, insurance and billing concerns would prove extremely helpful for families.

Finally, coordinated care transitions were highlighted as important, especially maintenance of partnerships with families and new care teams and continuity of information. Children recovering from TBI often require ongoing rehabilitation and coordinating these efforts is challenging for families. Case management assistance would be a valuable tool for families during the acute care period, during transition periods and upon arrival home.

Limitations

There are several study limitations. Study data are based on parents’ recall of the acute care experience and the range of time after TBI was large, leading to the potential for recall bias. Because families were interviewed at different time points from the date of their child's injury, it is possible that parents whose acute care experience was more recent were more likely to accurately report information about their child's care. In addition, only mothers of patients volunteered to participate in the study; additional measures to include fathers in future studies are warranted. However, despite these limitations, we were able to derive themes and new FCC model that may be helpful in improving the quality of care provided to families after TBI.

CONCLUSION

In this in-depth qualitative study, we present a family-centered TBI critical care model based on family perspectives. In addition to communication and coordination strategies, the model presents methods to address cultural and structural barriers to meeting the needs of families with LEP. Given the stress experienced by families of children with TBI, careful consideration of the factors associated with the three major themes identified here may assist in improving overall quality of care to families of hospitalized children with TBI. Future research to test the model in acute care settings is warranted.

ACKOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Ms. Harriet Saxe for her coordination of the study and the researchers at the Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center for their feedback on the model development.

Source of Funding: Supported by the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R01NS072308 PI:Vavilala) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (KL2TR000421 to Dr. Moore; PI: Nora Disis). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors report no conflicts of interest or financial relationships relevant to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centered approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(4):CD003267. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollack MM, Koch MA. Association of outcomes with organizational characteristics of neonatal intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1620–1629. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000063302.76602.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, et al. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1877–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ammentorp J, Mainz J, Sabroe S. Parents’ priorities and satisfaction with acute pediatric care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(2):127–131. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemmelgarn AL, Dukes D. Emergency room culture and the emotional support component of family-centered care. Child Health Care. 2001;30(2):93–110. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient-and Family-Centered Care: Patient-and family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2012;129:394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Hospital Care Family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2003;112:691–696. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, et al. Family satisfaction with care in the intensive care unit: Results of a multiple center study. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1413–1418. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coker TR, Rodriguex MA, Flores G. Family-centered care for US children with special health care needs: Who gets is it and why? Pediatrics. 2010;124:1159–1167. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long AC, Curtis JR. The epidemic of physician-family conflict in the ICU and what we should do about it. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):461–462. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a525b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fassier T, Azoulay E. Conflicts and communication gaps in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010;16:654–665. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834044f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aitken ME, Mele N, Barrett KW. Recovery of injured children: parent perspectives on family needs. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roscigno CI, Swanson KM. Parents’ experiences following children's moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: a clash of cultures. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:1413–1426. doi: 10.1177/1049732311410988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bond AE, Draeger CR, Mandleco B, Donnelly M. Needs of family members of patients with severe traumatic brain injury: Implications for evidence-based practice. Critical Care Nurse. 2003;23:63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gubrium JF, Holstein JA. Handbook of interview research: Context & method. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Available at http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1089/2385.

- 21.Cavanagh S. Content analysis: concepts, methods and applications. Nurse Researcher. 1997;4(3):5–16. doi: 10.7748/nr.4.3.5.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn MS, Reilly MC, Johnston AM, Hoopes RD, Abraham MR. Development and dissemination of potentially better practices for the provision of family-centered care in neonatology: the family-centered care map. Pediatrics. 2006;118:S95–S107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0913F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rusinova K, Kukal J, Simek J, Cerny V. Limited family members/staff communication in intensive care units in the Czech and Slovak republics considerably increases anxiety in patients’ relatives-the DEPRESS study. BMC Psyciatry. 2014;27:14–21. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peigne V, Chaize M, Falissard B, et al. Important questions asked by family members of intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:1365–1371. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182120b68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngui EM, Flores G. Satisfaction with care and ease of using health care services among parents with children with special health care needs: the roles of race/ethnicity, insurance, language and adequacy of family-centered care. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1184–1196. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]