Abstract

Objective

Delayed enteral nutrition (EN), defined as EN started ≥ 48 hours after admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) is associated with an inability to achieve full EN and worse outcomes in critically ill children. We reviewed nutritional practices in 6 medical-surgical PICUs and determined risk factors associated with delayed EN in critically ill children.

Design

Retrospective cross-sectional study using medical records as source of data

Setting

Six medical-surgical PICUs in northeastern United States

Patients

Children < 21 years old admitted to the PICU for ≥ 72 hours excluding those awaiting or recovering from abdominal surgery.

Measurements/Main Results

A total of 444 children with a median age of 4.0 years were included in the study. EN was started at a median time of 20 hours after admission to the PICU. There was no significant difference in time to start EN among the PICUs. Of those included, 88 (19.8%) children had delayed EN. Risk factors associated with delayed EN were: non-invasive (odds ratio [OR]: 3.37; 95% CI: 1.69-6.72) and invasive positive pressure ventilation (OR: 2.06; 95% CI: 1.15-3.69), severity of illness, (OR for every 0.1 increase in Pediatric Index of Mortality 2 score: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.14-1.71) as well as procedures (OR 3.33; 95% CI: 1.67-6.64) and; gastrointestinal disturbances (OR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.14-3.68) within 48 hours after admission to the PICU. Delayed EN was associated with failure to reach full EN while in the PICU (OR 4.09; 95% CI: 1.97-8.53). Nutrition consults were obtained in less than half of the cases and none of the PICUs employed tools to assure the adequacy of energy and protein nutrition.

Conclusions

Institutions in this study initiated EN for a high percentage of patients by 48 hours of admission. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation was most strongly associated with delay EN. A better understanding of these risk factors and assessments of nutritional requirements should be explored in future prospective studies.

Keywords: nutrition, enteral nutrition, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV), vasopressors, procedures, gastrointestinal

Introduction

Providing adequate nutrition to critically ill children is both crucial and challenging. Critically ill children have fewer energy reserves and more variable protein and energy requirements than critically ill adults (1, 2). During a time of profoundly altered metabolism, the afflicted child must satisfy not just current nutritional needs, but also the demands of somatic and neurological development. Malnutrition, which is commonly noted in children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), persists throughout the hospitalization, and has been associated with a complicated PICU course and increased mortality (2-4). Suboptimal nutrition during this period can exacerbate these problems (1).

Enteral nutrition (EN) is the preferred route in children with an intact gut. Compared with parenteral nutrition, EN may be easier to initiate, less costly and associated with lower risk of infection (5, 6). In addition, EN has been associated with improved nutritional indices and clinical outcomes including a nearly 4-fold decrease in mortality in critically ill, mechanically ventilated children (3, 7, 8).

Early EN, though variably defined by investigators, promotes the achievement of energy and protein nutrition goals and is associated with improved survival in children in the PICU (9-12). In a multicenter retrospective study of 5105 critically ill children, 40% of them had EN delayed beyond 48 hours after admission to the PICU. Those who received early EN had nearly double the rate of survival from the PICU compared with those for whom EN was delayed (10). Morbidity and mortality benefits from early EN have been also been shown across a range of critical illness, including those with severe burn and traumatic brain injury (11, 13, 14). As a result, greater scrutiny is warranted for factors that interfere with both the advancement and initiation of EN.

Much of the current literature relates to barriers to achieving caloric goals for EN in the PICU. These barriers can be divided into patient characteristics (e.g. severity of illness, diagnosis and gastrointestinal intolerance) and treatment factors (e.g. use of neuromuscular blockers, vasoactive medications, mechanical ventilation and procedures) (15-17). Little is known about obstacles to the initiation of EN although it is probable that they would be similar to those associated with the inability to achieve nutritional goals. Since many of the obstacles to achieving nutritional goals may be modifiable, it is possible that barriers to initiation of EN may be modifiable as well (12, 16, 18). The aim of this study was to determine the factors associated with delayed EN in critically ill children.

Subjects and Methods

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of nutritional practices across 6 PICUs in northeastern United States: Baystate Children's Hospital, Connecticut Children's Medical Center (CCMC), Maria Fareri Children's Hospital (MFCH), University of Massachusetts Memorial Children's Medical Center, Women and Children's Hospital of Buffalo and Yale-New Haven Children's Hospital (YNHCH) in 4 discontinuous months in 2011 to capture the seasonal variation of diagnoses in critically ill children. All participating PICUs admit medical-surgical children while 3 of them also care for post-operative cardiac children (CCMC, MFCH and YNHCH). When combined, the 6 PICUs represent an annual admission rate of nearly 6,000 children and a total of 91 beds. The Institutional Review Board of each institution approved the study and granted waivers of consent.

Subjects

The study included all children <21years old who were admitted to the participating PICUs for ≥72 hours. This period was selected to exclude children with low severity of illness or those who were moribund on admission. Children who were admitted for abdominal surgery were excluded as they are typically not fed during the initial days before and after the surgery. We identified eligible subjects using cost-accounting databases maintained at each participating institutions. Each patient's medical records were reviewed to confirm eligibility.

Data Collection

All data were collected from the patient's medical records. We abstracted the patient's age, weight, z score of weight for age, gender, severity of illness expressed as pediatric index of mortality 2 (PIM 2) score and diagnosis on admission. At 48 hours after admission, we recorded whether the patient was receiving respiratory support (none, non-invasive or invasive positive pressure ventilation), neuromuscular blockade, vasopressors or fluid restriction, and whether procedures, gastrointestinal disturbances or nutrition consult had occurred. From admission, the following times were calculated: start of EN, achievement of full EN, nutrition consult (a registered hospital dietician), and discharge from the PICU. If performed, we collected data on studies used to assess the adequacy of nutrition (e.g., nitrogen balance calculation, indirect calorimetry, albumin, and prealbumin), urinalysis, and daily energy and protein intake calculation.

These data points were defined as follows:

Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) — bi-level (BiPAP) or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) ventilation via mask or nasal prongs, or high flow nasal cannula (HFNC)

Invasive positive pressure ventilation — respiratory support with mechanical ventilator via endotracheal tube or tracheostomy

Vasopressors — dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine or phenylephrine

Fluid restriction — intravenous fluids maintained at less than full maintenance

Procedures — included, but were not limited to endotracheal intubation, placement of a Central venous catheter or chest tube, surgical or radiologic interventions

Gastrointestinal disturbances — “excessive” gastric residual volumes as arbitrarily defined in each PICU, vomiting, abdominal distension, constipation and diarrhea

Early EN – enteral nutrition begun by 48 hours of admission with the intent to advance feeds regardless of mode of delivery (i.e., oral, nasogastric, nasojeujunal or via gastrostomy)

Full EN — 100% of the volume prescribed by the nutrition or care team

Statistical Analysis

We divided the children into 2 groups based on the time to start EN. EN was started <48 hours from PICU admission in children in the early EN group and ≥48 hours in those in the delayed EN group. Continuous, categorical and time to event data were compared using Mann-Whitney U, chi-square and log-rank tests, respectively. We performed logistic regression with backward elimination at a threshold of p>0.10 to identify potential risk factors for delayed EN. Based on prior literature and discussion among investigators, we hypothesized a priori that age, severity of illness, cardiac surgery, traumatic brain injury, cancer, higher levels of respiratory support, use of vasopressors, fluid restriction, procedures, gastrointestinal disturbances, or absence of nutritional consultation may be associated with delayed EN (18, 19).

We conservatively estimated that 40% of the children in the PICU would have delayed EN (1, 7, 16). We would need a minimum of 300 children to have sufficient statistical power for the regression model. This sample size would provide us with 10 children with delayed EN for each covariate in the model. Data is presented as median (inter-quartile range [IQR]) and counts (percentage), where appropriate. Magnitudes of association are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). All statistical analyses were evaluated at a 2-tailed level of significance of 0.05 and were performed using Stata 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

During the 4 study months, there were 444 children who fulfilled our eligibility criteria (Table 1). The median age was 4.0 years (IQR: 0.5-11.9 years) and 58.3% of them were males. The median PIM 2 score was 0.011 (IQR: 0.004-0.035). The most common diagnoses were respiratory (45.1%), neurologic (16.7%) and cardiovascular (12.4%).

Table 1. Characteristics of Children Included in this Study.

| All Children (n=444) | Early Enteral Nutrition (n=356) | Delayed Enteral Nutrition (n=88) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site of admission (% of total/by site) | 0.53 | |||

| PICU A | 60 (13.5) | 45 (12.6/75) | 15 (17.1/25) | |

| PICU B | 81 (18.2) | 62 (17.4/76) | 19 (21.6/24) | |

| PICU C | 64 (14.4) | 50 (14.0/78) | 14 (15.9/22) | |

| PICU D | 97 (21.9) | 83 (23.3/86) | 14 (15.9/14) | |

| PICU E | 22 (5.0) | 17 (4.8/77) | 5 (5.7/23) | |

| PICU F | 120 (27.0) | 99 (27.8/83) | 21 (23.9/17) | |

|

| ||||

| Age in years | 4.0 (0.5-11.9) | 4.1 (0.5-12.3) | 4.2 (0.8-11.1) | 0.73 |

|

| ||||

| Weight in kg | 15.0 (6.5-35.8) | 15.0 (6.5-35.1) | 17.2 (7.9-40.9) | 0.57 |

|

| ||||

| z-score of weight for age | -0.4 (-1.9−1.0) | -0.3 (-2.0−1.0) | -0.5 (-1.6−0.8) | 0.96 |

|

| ||||

| Male | 259 (58.3) | 205 (57.6) | 54 (61.4) | 0.52 |

|

| ||||

| PIM2 score | 0.011 (0.004-0.035) | 0.010 (0.004-0.031) | 0.015 (0.008-0.068) | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Diagnosis on admission | 0.02 | |||

| Trauma/Surgical | 21 (4.7) | 13 (3.7) | 8 (9.1) | |

| Cardiovascular | 55 (12.4) | 42 (11.8) | 13 (14.8) | |

| Respiratory | 200 (45.1) | 165 (46.4) | 35 (39.8) | |

| Neurologic | 74 (16.7) | 63 (17.7) | 11 (12.5) | |

| Toxic/Metabolic | 42 (9.5) | 28 (7.9) | 14 (15.9) | |

| Hematologic/Oncologic | 21 (4.7) | 20 (5.6) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Others | 31 (7.0) | 25 (7.0) | 6 (6.8) | |

|

| ||||

| Respiratory support | <0.001 | |||

| None | 222 (50.0) | 196 (55.1) | 26 (29.6) | |

| Non-invasive | 68 (15.3) | 48 (13.5) | 20 (22.7) | |

| Invasive | 154 (34.7) | 112 (31.5) | 42 (47.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Neuromuscular blockade | 44 (9.9) | 29 (8.2) | 15 (17.1) | 0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Vasopressors | 37 (8.3) | 23 (6.5) | 14 (15.9) | 0.004 |

|

| ||||

| Fluid restriction | 29 (6.5) | 22 (6.2) | 7 (8.0) | 0.55 |

|

| ||||

| Procedures | 154 (34.7) | 114 (32.0) | 40 (45.5) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Gastrointestinal disturbance | 138 (31.1) | 104 (29.2) | 34 (38.6) | 0.09 |

|

| ||||

| Nutrition consult | 217 (48.9) | 174 (48.9) | 43 (48.9) | 1.00 |

|

| ||||

| Full enteral nutrition while in the PICU | 401 (90.3) | 332 (93.3) | 69 (78.4) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Full enteral nutrition within 5 days in the PICU | 377 (84.9) | 325 (91.3) | 52 (59.1) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Length of stay in the PICU in days | 6.0 (3.8-10.1) | 5.8 (3.8-10.0) | 6.4 (3.9-10.5) | 0.72 |

Comparisons were made between early vs. delayed enteral nutrition. Data presented as counts (percentage) for categorical variables or median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. PICU – pediatric intensive care unit; PIM2 – pediatric index of mortality 2

Nutrition services were consulted for 48.9% of the children. The consults occurred at a median of 39 hours (IQR: 20-67 hours) after admission to the PICU. Multiple tools, including the World Health Organization, Seashore and Schofield equations and Dietary Reference Intakes, Mifflin-St. Jeor and Ireton-Jones formulas, were used to estimate energy requirements. Daily energy calculation occurred in 57.0% of children. Serum albumin was measured in 41.0% of the children, whereas prealbumin was assessed in only 3.8% of the children. None of the PICUs used indirect calorimetry to measure resting energy expenditure nor calculated protein balance. Only one of 6 PICUs had a formal nutrition protocol in place and only one had a clearly defined and enforced policy on gastric residual volumes and one PICU proscribed its measurement.

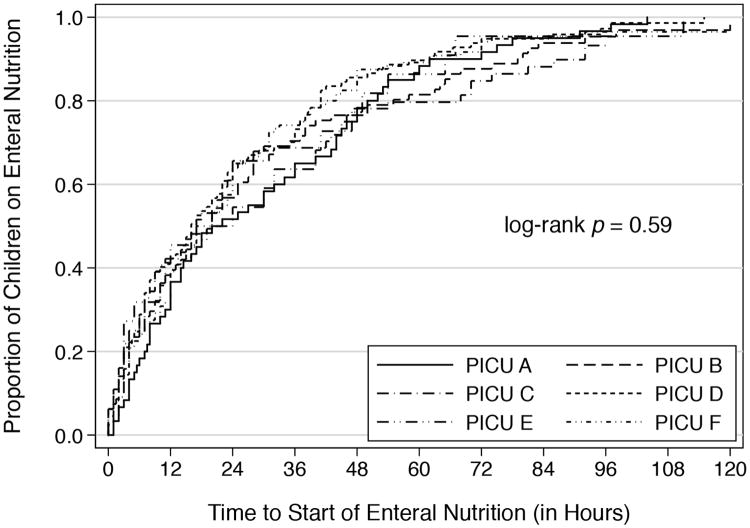

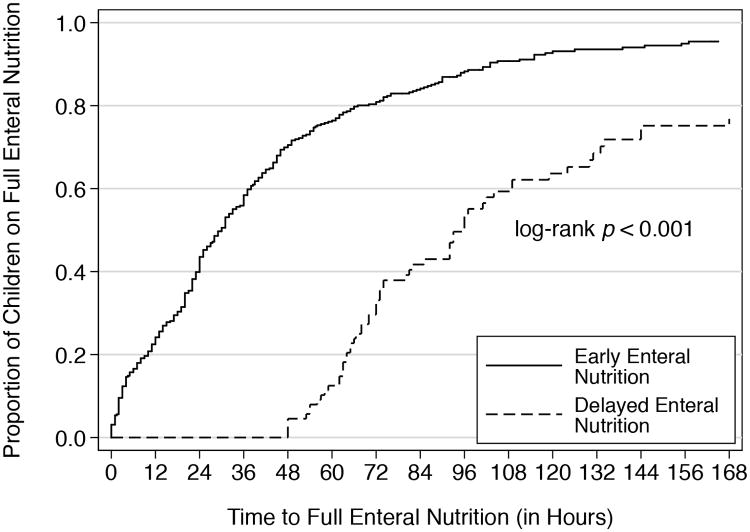

EN was started at a median time of 20 hours (IQR: 6-42 hours) after admission to the PICU (Figure 1). There was no significant difference in the time to start EN among the 6 PICUs (p=0.59). A total of 356 (80.2%) and 88 (19.8%) children were included in the early and delayed EN groups, respectively (Table 1). In the unadjusted analyses, children with delayed EN were more severely ill than those who had early EN. The distribution of diagnoses on admission was also different between groups with trauma (p= 0.03) and toxic ingestion (p= 0.02) more common in the delayed EN group. At 48 hours after admission, children with delayed EN had higher levels of respiratory support, were more likely to be receiving neuromuscular blockade or vasopressors, and more likely to have had a procedure. The median times to full EN in the early and delayed EN groups were 30 hours (IQR: 13-56 hours) and 96 hours (IQR: 67-144 hours), respectively (p<0.001) (Figure 2). While in the PICU, 93.3% of children with early EN and 78.4% with delayed EN received full EN (p<0.001). Compared with the delayed EN group, the OR of achieving full EN in the early group was 3.81 (95% CI 1.98-7.34). The association remained significant after adjusting for severity of illness, length of stay in the PICU and site (OR: 4:09; 95% CI: 1.97-8,53). The lengths of stay in the PICU were similar between the 2 groups.

Figure 1. Time to Start Enteral Nutrition (in hours).

Figure 2. Time to Full Enteral Nutrition (in hours).

The level of respiratory support at 48 hours was associated with delayed EN. Compared with no support, the OR of delayed EN in children with NPPV and invasive positive pressure ventilation were 3.37 (95% CI: 1.69-6.72) and 2.06 (95% CI: 1.15-3.69), respectively. Other factors associated with delayed EN were severity of illness (OR for every 0.1 increase in PIM2 score: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.14-1.71), procedures (OR: 3.33; 95% CI: 1.67-6.64) and gastrointestinal disturbances (OR 2.05; 95% CI: 1.14-3.68) within 48 hours of admission to the PICU (Table 2). Neuromuscular blockade at 48 hours, which was significant in the unadjusted analysis but was not pre-specified, was not associated with delayed EN in the full model (OR 1.35; 95% CI: 0.56-3.23) and was eliminated.

Table 2. Multivariable analysis showing the risk factors associated with delayed enteral nutrition.

| Full Model | Final Model* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value |

| Site of admission | 0.62 | |||||

| PICU A | Referent | |||||

| PICU B | 1.80 | 0.74-4.39 | 0.20 | |||

| PICU C | 0.91 | 0.37-2.23 | 0.83 | |||

| PICU D | 0.92 | 0.37-2.30 | 0.86 | |||

| PICU E | 0.81 | 0.21-3.08 | 0.76 | |||

| PICU F | 1.10 | 0.47-2.60 | 0.83 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.01 | 0.97-1.05 | 0.58 | |||

|

| ||||||

| PIM2 score (per 0.1 increase) | 1.33 | 1.07-1.65 | 0.01 | 1.39 | 1.14-1.71 | 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Cardiac surgery | 1.61 | 0.47-5.45 | 0.45 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Traumatic brain injury | 2.33 | 0.81-6.73 | 0.12 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Cancer | 0.55 | 0.18-1.69 | 0.30 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Respiratory support at 48 hours | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||||

| None | Referent | Referent | ||||

| Non-invasive | 4.32 | 2.02-9.20 | <0.001 | 3.37 | 1.69-6.72 | 0.001 |

| Invasive | 2.21 | 1.15-4.27 | 0.02 | 2.06 | 1.15-3.69 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Vasopressor at 48 hours | 1.20 | 0.50-2.85 | 0.68 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Fluid restriction | 1.18 | 0.41-3.39 | 0.76 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Procedures | 1.74 | 0.99-3.08 | 0.06 | 3.33 | 1.67-6.64 | 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Gastrointestinal disturbance | 1.94 | 1.13-3.32 | 0.02 | 2.05 | 1.14-3.68 | 0.02 |

| Nutrition consult at 48 hours | 0.72 | 0.41-1.26 | 0.25 | |||

Risk factors for final model were selected using backward stepwise selection at a threshold p<0.10. PICU – pediatric intensive care unit; PIM2 – pediatric index of mortality 2

Discussion

This study presents a snapshot of current nutritional practices in 6 medical-surgical PICUs in northeastern United States. We found that higher levels of respiratory support, increased severity of illness, procedures, and gastrointestinal disturbances were associated with delayed EN. NPPV has not been previously associated with delayed EN. Our review of PICU management at the participating institutions also revealed a broad commitment to early EN, but there was significant variance in practice when compared with current consensus guidelines and recent research.

A total of 80.2% of our patients received early EN. This level was higher than anticipated, but a wide range has been described (1, 10, 12, 17). Consistent with previous reports, early EN increased the odds of reaching goals feeds in our cohort (20). Yet even more important than this advantage may be the association that has been described between early EN and clinical outcomes such as mortality (10, 11). Since there are few absolute contraindications to its use, it is reasonable to examine perceived obstacles to initiating EN in critically ill children.

Prior investigation has associated invasive mechanical ventilation with both the promotion and delay of EN, yet the influence of NPPV in this context has not been evaluated (10, 17). The practice has been safely performed in very low birth weight premature infants but there is limited data on its safety when used in older children (21). This is an issue of growing relevance as the use of NPPV is increasingly employed as definitive, rather than “bridging” therapy. Our results are more consistent with the historic reluctance to enterally feed critically ill children on NPPV than attitudes expressed recently by pediatric intensivists. Of 81 intensivists surveyed, 91% did not view NPPV as a contraindication to starting EN (22). If one assumes similar advantages from EN in children on NPPV compared with other critically ill children, attention should be paid to the discordance between attitude and practice. Future efforts could more clearly define the risks of EN, such as aspiration, in children on NPPV and explore methods (e.g. post-pyloric feeding tubes) to attenuate them (23, 24).

Severity of illness was associated with delayed EN in our study, suggesting that EN was often withheld from the “sickest” patients. It is interesting that this risk factor is not consistently described as a threat to achieving full EN (12, 18). In fact, PICU caregivers have acknowledged a greater reluctance to start EN for patients who are “too ill” than those frankly “hemodynamically unstable” (25). This attitude is reflected in our study in which severity of illness, but not vasopressor use, was associated with delayed EN. Interestingly, severity of illness scores have not been shown to predict the safety and tolerance of EN and there is no recognized risk of mortality above which EN is contraindicated (26, 27). In addition, observational studies have described the safety and benefits of EN in children on vasopressors and threats posed by these agents may be related to the particular vasopressor/s or doses employed (28-30)

The performance of procedures is frequently described as delaying EN. Many of these procedures may be unavoidable in the course of providing care. Nonetheless, anticipating or grouping these interruptions may lead to a more rapid, predictable initiation or advancement of EN (17, 18).

Gastrointestinal disturbances represent a range of perturbations, the severity and clinical relevance of which is highly variable and largely speculative. For example, lack of agreement as to what constitutes significant residual volumes or abdominal distension has made it difficult to assess the true impact each has on EN. Recently published protocols defining these common disturbances could promote a more consistent--and testable--approach to managing EN (16, 17, 31).. It is worth noting that even in extreme cases (very low birth weight, premature infants at risk for necrotizing enterocolitis), the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) recommends the initiation of EN by 48 hours (32).

Early EN was widely practiced at our institutions even in the absence of nutrition consults for nearly half of the patients and formal feeding protocols in only 1 of the 6 PICUs, both of which have been shown to encourage EN (17, 31). The heterogeneity of tools used to estimate energy requirements among the PICUs is consistent with the variability noted in the literature (33, 34). This variability may be related to the lack of superiority of any one of these tools over the others in estimating actual energy requirements in critically ill children (17, 35). In recognition of this limitation, ASPEN recommends the judicious use of indirect calorimetry (36). This tool was used in approximately 17% of PICUs surveyed in Europe, but none in our group. Prealbumin, a marker for adequate nutrition, was rarely measured. Finally, none of the PICUs in our study measured protein balance in spite of mounting data supporting the importance protein metabolism in the management of critically ill children (1, 9, 16, 37).

The main strength of our study is that it was conducted in settings where most critically ill children in the US receive their care (i.e., medical-surgical PICUs with less than 20 beds), and with a group of children whose breadth of diagnosis is similar to that described in other reports (31, 38). In addition, the severity of illness as represented by a rate of mechanical ventilation of 35% at 48 hours is comparable to that described in other PICU nutrition studies (10). By excluding children who were admitted to the PICU for <72 hours, our patient population is likely representative of children who would most benefit from EN; i.e., those who died soon after admission and those who were relatively well, were eliminated.

There were a number of limitations to acknowledge. Our study is retrospective and relied on the interpretation of medical records as the source of data. Although we provided definitions for data collection, clinicians may have documented differently across the 6 PICUs. It is also not possible to discern the providers' rationale and intent regarding the initiation or delay of EN. Based on prior studies, we anticipated the frequency of delayed EN to be approximately 40%, which was double that of our study. Sample size estimates based on this assumption may have led us to miss other important risk factors for delayed EN. This study was not designed to look at clinical outcomes such as mortality or PICU length of stay. Interestingly, early EN was associated with longer PICU stays in a recent study (10). We did not distinguish between enteral and post-pyloric feeds. This prevented us from analyzing the association between mode of delivery of EN and delay in its initiation. We censored the observations upon discharge from the PICU after which children may have achieved full EN rapidly. However, this is unlikely based on the data we presented.

In conclusion, the 6 medical-surgical PICUs participating in this study demonstrated a consistent commitment to providing early EN. Increased levels of respiratory support, severity of illness, procedures and gastrointestinal disturbances were associated with delayed EN. These risk factors could be more clearly defined and possibly modified by future prospective studies. Finally, we have described deficiencies and areas in which our PICUs could more accurately determine and satisfy nutritional needs.

Acknowledgments

William Bortcosh, MD and Nirupama Krishnamurthi, MBBS, MPH for research assistance.

Sources of funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CTSA Grants Numbers UL1 TR000142 and KL2 TR000140) and American Heart Association (Award Number 14CRP20490002) to Dr. Faustino.

Footnotes

The other authors do not have any real or perceived conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Michael F. Canarie, Department of Pediatrics, Yale University School of Medicine, P.O. Box 208064, New Haven, CT 06520-8064, 203-785-4561.

Suzanne Barry, Email: suzanne.barry@nemours.org, Department of Pediatric Critical Care, Nemours, AI duPont Hospital for Children, 1600 Rockland Rd, Wilmington, DE 19803, 302-651-4200.

Christopher L. Carroll, Email: ccarroll@connecticutchildrens.org, Department of Pediatrics, Connecticut Children's Medical Center, 282 Washington Street, Hartford, CT 06106, 860-545-9850.

Amanda Hassinger, Email: albrooks@buffalo.edu, Department of Pediatrics, Women and Children's Hospital of Buffalo, 219 Bryant Street, Buffalo, NY 14222, 716-878-1859.

Sarah Kandil, Email: Sarah.kandil@yale.edu, Department of Pediatrics, Yale University School of Medicine, P.O. Box 208064, New Haven, CT 06520-8064, Tel: 203-785-4561.

Simon Li, Email: Lis@wcmc.com, Marie Fareri Children's Medical Center, 100 Woods Rd. Valhalla, NY 10595, 914-493-7513.

Matthew Pinto, Email: pintom@wcmc.com, Marie Fareri Children's Medical Center, 100 Woods Rd., Valhalla, NY 10595, 914-493-7513.

Stacey Lynn Valentine, Email: Stacey.valentine@umassmemorial.org, Department of Pediatrics, University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester MA 01566; Department of Anesthesia, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Division of Critical Care Boston Children's Hospital 300 Longwood Ave, Boston MA 02115.

E. Vincent S. Faustino, Email: vince.faustino@yale.edu, Department of Pediatrics, Yale University School of Medicine, P.O. Box 208064, New Haven, CT 06520, 203-785-4561.

References

- 1.Hulst JM, van Goudoever JB, Zimmermann LJ, et al. The effect of cumulative energy and protein deficiency on anthropometric parameters in a pediatric ICU population. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:1381–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollack MM, Ruttimann UE, Wiley JS. Nutritional depletions in critically ill children: associations with physiologic instability and increased quantity of care. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 1985;9:309–313. doi: 10.1177/0148607185009003309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briassoulis G, Zavras N, Hatzis T. Malnutrition, nutritional indices, and early enteral feeding in critically ill children. Nutrition. 2001;17:548–557. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(01)00578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leite HP, Isatugo MK, Sawaki L, et al. Anthropometric nutritional assessment of critically ill hospitalized children. Rev Paul Med. 1993;111:309–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joosten K, de Betue C. Adequate enteral feeding in the pediatric intensive care unit may be associated with fewer nosocomial infections and deaths. Evid Based Med. 2013;18:151–152. doi: 10.1136/eb-2012-100974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pritchard C, Duffy S, Edington J, et al. Enteral nutrition and oral nutrition supplements: a review of the economics literature. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2006;30:52–59. doi: 10.1177/014860710603000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Cahill N, et al. Nutritional practices and their relationship to clinical outcomes in critically ill children--an international multicenter cohort study. Critical Care Medicine. 2012;40:2204–2211. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e18a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurgueira GL, Leite HP, Taddei JA, et al. Outcomes in a pediatric intensive care unit before and after the implementation of a nutrition support team. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2005;29:176–185. doi: 10.1177/0148607105029003176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Zurakowski D, et al. Adequate enteral protein intake is inversely associated with 60-d mortality in critically ill children: a multicenter, prospective, cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015 May 13; doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.104893. as. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikhailov TA, Kuhn EM, Manzi J, et al. Early Enteral Nutrition Is Associated With Lower Mortality in Critically Ill Children. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2014;38:1673–1684. doi: 10.1177/0148607113517903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khorasani EN, Mansouri F. Effect of early enteral nutrition on morbidity and mortality in children with burns. Burns. 2010;36:1067–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keehn A, O'Brien C, Mazurak V, et al. Epidemiology of Interruptions to Nutrition Support in Critically Ill Children in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2015;39:211–217. doi: 10.1177/0148607113513800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vavilala MS, Kernic MA, Wang J, et al. Acute care clinical indicators associated with discharge outcomes in children with severe traumatic brain injury. Critical Care Medicine. 2014;42:2258–2266. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taha AA, Badr L, Westlake C, et al. Effect of early nutritional support on intensive care unit length of stay and neurological status at discharge in children with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;43:291–297. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e318234e9b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Menezes FS, Leite HP, Nogueira PC. What are the factors that influence the attainment of satisfactory energy intake in pediatric intensive care unit patients receiving enteral or parenteral nutrition? Nutrition. 2013;29:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Neef M, Geukers VG, Dral A, et al. Nutritional goals, prescription and delivery in a pediatric intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton S, McAleer DM, Ariagno K, et al. A stepwise enteral nutrition algorithm for critically ill children helps achieve nutrient delivery goals. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:583–589. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta NM, McAleer D, Hamilton S, et al. Challenges to optimal enteral nutrition in a multidisciplinary pediatric intensive care unit. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2010;34:38–45. doi: 10.1177/0148607109348065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulst JM, Joosten KF, Tibboel D, et al. Causes and consequences of inadequate substrate supply to pediatric ICU patients. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:297–303. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000222115.91783.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez EE, Bechard LJ, Mehta NM. Nutrition algorithms and bedside nutrient delivery practices in pediatric intensive care units: an international multicenter cohort study. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:360–367. doi: 10.1177/0884533614530762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amendolia B, Fisher K, Wittmann-Price RA, et al. Feeding tolerance in preterm infants on noninvasive respiratory support. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2014;28:300–304. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leong AY, Cartwright KR, Guerra GG, et al. A Canadian survey of perceived barriers to initiation and continuation of enteral feeding in PICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:e49–55. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chellis MJ, Sanders SV, Dean JM, et al. Bedside transpyloric tube placement in the pediatric intensive care unit. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 1996;20:88–90. doi: 10.1177/014860719602000188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meert KL, Daphtary KM, Metheny NA. Gastric vs small-bowel feeding in critically ill children receiving mechanical ventilation: a randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2004;126:872–878. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tume L, Carter B, Latten L. A UK and Irish survey of enteral nutrition practices in paediatric intensive care units. Br J Nutr. 2013;109:1304–1322. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512003042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez C, Lopez-Herce J, Mencia S, et al. Clinical severity scores do not predict tolerance to enteral nutrition in critically ill children. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:191–194. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508159049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briassoulis GC, Zavras NJ, Hatzis MT. Effectiveness and safety of a protocol for promotion of early intragastric feeding in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001;2:113–121. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panchal AK, Manzi J, Connolly S, et al. Safety of Enteral Feedings in Critically Ill Children Receiving Vasoactive Agents. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0148607114546533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Herce J, Mencia S, Sanchez C, et al. Postpyloric enteral nutrition in the critically ill child with shock: a prospective observational study. [Accessed September 1, 2014];Nutr J. 2008 doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-7-6. Available at: http://www.jpen.sagepub.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Nygren A, Thoren A, Ricksten SE. Effects of norepinephrine alone and norepinephrine plus dopamine on human intestinal mucosal perfusion. Intensive Care Medicine. 2003;29:1322–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Betue CT, van Steenselen WN, Hulst JM, et al. Achieving energy goals at day 4 after admission in critically ill children; predictive for outcome? Clin Nutr. 2015;34:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fallon EM, Nehra D, Potemkin AK, et al. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: nutrition support of neonatal patients at risk for necrotizing enterocolitis. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2012;36:506–523. doi: 10.1177/0148607112449651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Framson CM, LeLeiko NS, Dallal GE, et al. Energy expenditure in critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2007;8:264–267. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000262802.81164.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vazquez Martinez JL, Martinez-Romillo PD, Diez Sebastian J, et al. Predicted versus measured energy expenditure by continuous, online indirect calorimetry in ventilated, critically ill children during the early postinjury period. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:19–27. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000102224.98095.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Oliveira Iglesias SB, Leite HP, Santana e Meneses JF, et al. Enteral nutrition in critically ill children: are prescription and delivery according to their energy requirements? Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22:233–239. doi: 10.1177/0115426507022002233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mehta NM, Compher C. A.S.P.E.N. Clinical Guidelines: nutrition support of the critically ill child. JPEN Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2009;33:260–276. doi: 10.1177/0148607109333114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bechard LJ, Parrott JS, Mehta NM. Systematic review of the influence of energy and protein intake on protein balance in critically ill children. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2012;161:333–339 e331. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faustino EV, Hanson S, Spinella PC, et al. A multinational study of thromboprophylaxis practice in critically ill children. Critical Care Medicine. 2014;42:1232–1240. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]