Abstract

Background

Family caregivers (FCGs) experience significant deteriorations in quality of life while caring for lung cancer patients. This study tested the effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention for FCGs of patients diagnosed with stage I–IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

FCGs who were identified by patients as the primary caregiver were enrolled in a prospective, quasi-experimental study whereby the usual care group was accrued first followed by the intervention group. FCGs in the intervention group were presented at interdisciplinary care meetings, and they also received four educational sessions organized in the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. The sessions included self-care plans to support the FCG’s own needs. Caregiver burden, caregiving skills preparedness, psychological distress, and FCG QOL were assessed at baseline and 12 weeks using validated measures.

Results

A total of 366 FCGs were included in the primary analysis. FCGs who received the interdisciplinary palliative care intervention had significantly better scores for social well-being (5.84 vs. 6.86; p<.001) and lower psychological distress (4.61 vs. 4.20; p=.010) at 12 weeks compared to FCGs in the usual care group. FCGs in the intervention group had significantly less caregiver burden compared to FCGs in the usual care group (p=.008).

Conclusions

An interdisciplinary approach to palliative care in lung cancer resulted in statistically significant improvements in the FCG’s social well-being, psychological distress, and less caregiver burden.

Introduction

A cancer diagnosis can profoundly impact the quality of life (QOL) for both patients and their family caregivers (FCGs). The cancer caregiving role is associated with physical and psychological burden, and this may be more pronounced with lung cancer.1 Numerous studies have documented cancer’s negative effect on FCGs, including increased psychological distress, family/social/spouse relationship disruptions, higher incidence of cardiac diseases, and substantial impact on the FCG’s economic well-being.2–6

Many FCGs of lung cancer patients report physical and mental health that is worse than population norms.7,8 In a qualitative study, Mosher and colleagues found that the most common FCG challenge included a profound sense of uncertainty about the future and the patient’s prognosis, managing the patient’s emotional reactions to lung cancer, and accomplishing practical tasks including coordinating the patient’s medical care.9 Distressed FCGs reported one or more negative economic or social changes since diagnosis, including reductions in social and leisure activity participation and reduced work hours.10 Many FCGs reported quitting work, losing their main source of family income, losing most or all of their savings, and making substantial lifestyle changes due to caregiving.10,11 Despite the high level of clinically meaningful psychological distress, the majority of FCGs did not access mental health or support services, even though many expressed interest in professional help for emotional and practical needs.12 Our previous research suggests that as the patient transitions through initial diagnosis and treatment, caregiver burden and psychological distress increases, while perceived caregiving skills preparedness and QOL decreased over time.13 Increased FCG psychological distress was associated with three factors, including ability to maintain QOL (self-care component), perception of caregiving preparedness and caregiving demands (FCG role component), and the emotional reaction to caregiving (FCG stress component).14

FCGs receive minimal attention within the current healthcare system, whose focus is primarily on the needs of patients. Evidence-based care models are needed to support FCGs in their caregiving role. The purpose of this National Cancer Institute-supported Program Project was to test the effectiveness of an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention in FCGs of patients diagnosed with stage I–IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The Program Project supported the simultaneous testing of the palliative care intervention in both patients and FCGs. This paper presents findings from the FCG project, as well as a comparative analysis of key patient and FCG outcomes (psychological distress and QOL). We hypothesized that FCGs who received the interdisciplinary palliative care intervention would experience improved QOL, lower psychological distress, reduced caregiver burden, and improved caregiving skills preparedness. We also hypothesized that the effect of the intervention on psychological distress and QOL will be different for patients and FCGs.

Materials and Methods

Study and Intervention Design

A two-group, prospective sequential, quasi-experimental design was used in which FCGs were enrolled into the usual care group first, followed by intervention group enrollment. This study design was selected, as opposed to a randomized design, to minimize the risk of usual care group contamination, resulting in potential confounding effects on outcomes. FCG enrollment was stratified based on matching patient’s disease stage (early versus late). Enrollment occurred between November 2009 to December 2010 for usual care, and between July 2011 and August 2014 for the intervention group. Data collection concluded in September 2014. The study was conducted at one NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center in Southern California, and all study procedures and protocols were approved by the institutional review board.

The study’s conceptual framework combines Adult Teaching Principles, the NCCN Guidelines for Distress Screening15, the IOM Report on Cancer Care for the Whole Patient16, the National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care17, and the Self-Care concept. The Adult Teaching Principles acknowledge the need for education to be responsive to the individual’s goals and preferences. The NCCN Guidelines on Distress Screening, the IOM report, and the NCP Guidelines provided standards of care and recognized that FCG’s needs are an integral component of quality psychosocial and palliative care. The self-care concept and evidence suggest that FCGs often forget to manage their own co-morbidities and have decreasing ability to cope with the stresses of caregiving.1 Therefore, FCG self-care support is essential to improving well-being.

The palliative care intervention consisted of three key components. Nurses completed a comprehensive baseline QOL assessment for both patients and FCGs. Assessment results were transferred to a personalized palliative care plan, with QOL issues categorized into the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. Guided by the palliative care plan, patients and FCGs were presented at weekly interdisciplinary care meetings. Nurses, palliative medicine clinicians, thoracic surgeons, medical oncologists, geriatric oncologist, pulmonologist, social worker, chaplain, dietitian, physical therapist, and key members of the research team attended the team meetings. Recommendations were made on how to support both patients and FCGs based on the assessments. These recommendations included symptom management and supportive care referrals for patients, and supportive care referrals (social work, chaplaincy) and available community resources for FCGs. Overall, 139 interdisciplinary care meetings were conducted between July 2011 and August 2014, with each case presentation lasting approximately 20 minutes.

FCGs also received four educational sessions, with content categorized by the four QOL domains (Table 1). Content for FCGs also included a personalized self-care plan with strategies to support FCG QOL. FCGs received a manual that contained all teaching content organized in the four QOL domains. The FCG teaching sessions averaged 28 minutes. FCGs and patients in the usual care group had access to all supportive and palliative care services while on study.

Table 1.

Family Caregiver Education Session Content

| PHYSICAL WELL BEING |

| Fatigue |

| Pain |

| Appetite |

| Dyspnea/Cough |

| Sleep |

| Nausea/Vomiting |

| Constipation/Diarrhea |

| Skin, Nail, Hair Changes |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL WELL BEING |

| Anxiety |

| Depression |

| Anger |

| Cognitive Changes |

| SOCIAL WELL BEING |

| Communication |

| Health Care Planning |

| Relationships |

| Social Support |

| Financial Burden |

| Sexuality |

| SPIRITUAL WELL BEING |

| Purpose/Meaning |

| Hope |

| Inner Strength |

| Redefining Self & Priorities |

| Uncertainty |

Subjects

Patients with stage I–IV NSCLC were invited by their treating physician to participate in the study. Once enrolled, patients were asked to identify an FCG to participate in the study. For this study, an FCG refers to either a family member or friend identified by the patient as the primary caregiver. Patients who did not have an FCG were allowed to enroll in the study. Written informed consents were obtained for both patients and FCGs. FCGs were eligible if they were 21-years or older and had a matching patient enrolled in either the Early or Late stage projects.

FCG and Patient Outcome Measures

FCG QOL was assessed using the FCG version of the City of Hope QOL Tool (COH-QOL-FCG). This 37-item instrument measures FCG QOL in the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well being domains. Items are rated on a 1–10 scale, with higher scores representing worse QOL. A 10% to 20% difference in scores for the tool is considered clinically meaningful. The test-retest reliability was .89 and internal consistency was .69.18 Caregiver burden was assessed using the Montgomery Caregiver Burden Scale. This 14-item tool measures the impact of caregiving on three dimensions of burden: objective, subjective demand, and subjective stress. Each item is scaled from 1–5, and higher scores represent higher burden. Internal consistency for the three dimensions ranges from .81 to .90.19,20 Caregiving skills preparedness was assessed using Archbold’s Caregiving Preparedness Scale. This eight-item scale, scored from 0 to 4, evaluates FCG’s comfort with the physical and emotional patient needs. Higher scores represent better preparedness. Internal consistency ranges from 0.88 to 0.93.21

Patient’s QOL and symptoms were assessed using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) tool. It contains 27 items that measures physical, social/family, emotional, and functional well-being. The additional lung cancer subscale (LCS) assesses disease-specific symptoms. All items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0=not at all; 4=very much). Higher scores indicate better QOL, and the total score ranges from 0 to 140.22 Spiritual well-being was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spirituality Subscale (FACIT-Sp-12). This is a 12-item, 5-point Likert scale that assesses sense of meaning, peace, and faith in illness. Total score ranges from 0 to 48, and a higher score indicates better spiritual well-being.23 The Distress Thermometer (DT) was used to assess patient and FCG psychological distress. The DT is an efficient, low-burden screening tool, using a scale of 0 to 10 (higher score=more distress).24

Study Procedures

Patients and FCGs completed baseline questionnaires at enrollment. For the usual care group, FCGs completed follow-up questionnaires at 7 and 12 weeks, while patients were reevaluated at 6 and 12 weeks. For the intervention group, FCGs received the intervention’s teaching component at 6 weeks following completion of patient teaching. This “delayed” design was used to prevent treatment effect contamination between patients and FCGs. Data collection for the intervention group were identical to the usual care group procedures. All patient and FCG data were collected during in-person encounters at outpatient clinics or through mailed questionnaires.

Statistical Analysis

Data processing included scanning demographic and outcome measures and importing tracking data from an Access database. Data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, v. 21 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). All results are based on an intention-to-treat analysis. Consented FCGs who completed their baseline measurement were included for analysis (N=366). After an accuracy audit, data were matched by ID, and missing data were imputed using the SPSS Missing Values Analysis (MVA) procedure and the Estimation and Maximization (EM) method. Missing data for FCGs whose patients died while on study (N=24) were not imputed, as they were discontinued from the study. Selected demographic data were compared by group (intervention vs. usual care) and by disease stage (stages I–III vs. IV), using contingency table analysis and the chi square statistic, or student’s t-test, depending on measurement level.

The study hypotheses for the four main outcomes (QOL, psychological distress, caregiver burden, and caregiving skills preparedness), were tested using factorial Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) controlling for baseline scores with disease stage as a blocking variable and group as the factor. The three caregiver burden subscales were also collapsed into high and low burden scores as established in the literature19,20, and analyzed using contingency tables with the chi square statistic. FCG data were then merged with patient data, resulting in a total of 354 matched pairs to test the comparative analysis of patient and FCG psychological distress and QOL. A factorial repeated measures ANCOVA was used for this test, controlling for baseline scores with group as between subjects factor and the two twelve-week scores (FCG and patient) as within subjects factor.

Results

Baseline FCG Characteristics

After accounting for attrition, a total of 157 FCGs in the usual care group and 197 FCGs in the intervention group who had baseline assessments were included in the primary outcome analysis (N=354). Overall, 354 matched pairs (N=153 pairs for usual care; N=191 pairs for intervention) were included in the analysis of patient and FCG outcomes.

We observed significant between-group differences in baseline FCG demographic characteristics for work hours and race/ethnicity (Table 2). No statistically significant differences were observed for any other demographic characteristics.

Table 2.

FCG Demographic Characteristics by Group and Disease Stage

|

|

|

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Usual Care N (%) |

Intervention N (%) |

p-Value | Stage I-III N (%) |

Stage IV N (%) |

p-Value |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 59 (36.2%) | 80 (39.4%) | .588 | 51 (32.5%) | 88 (42.1%) | .065 |

| Female | 104 (63.8%) | 123 (60.6%) | 106 (67.5%) | 121 (57.9%) | ||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Education Completed | ||||||

| Elementary School | 2 (1.2%) | 1 (0.5%) | .071 | 1 (0.6%) | (1.0%) | .252 |

| Secondary/High School | 61 (37.4%) | 55 (27.1%) | 57 (36.3%) | 59 (28.2%) | ||

| College | 100 (61.3%) | 147 (72.4%) | 99 (63.1%) | 148 (70.8%) | ||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Single | 16 (9.9%) | 31 (15.3%) | .308 | 18 (11.5%) | 29 (13.9%) | .756 |

| Separated, Divorced, Widowed | 13 (8.0%) | 16 (7.9%) | 12 (7.6%) | 17 (8.2%) | ||

| Married, Partnered | 133 (82.1%) | 156 (76.8%) | 127 (80.9%) | 162 (77.9%) | ||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Live Alone | ||||||

| Yes | 6 (3.7%) | 15 (7.4%) | .175 | 10 (6.4%) | 11(5.3%) | .657 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Employed | ||||||

| > 32 hours per week | 56 (34.4%) | 48 (23.6%) | .027 | 45 (28.7%) | 59 (28.2%) | 1.000 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 11 (6.7%) | 24 (11.8%) | .015 | 15 (9.6%) | 20 (9.6%) | .585 |

| NOT Hispanic/Latino | 145 (89.0%) | 178 (87.7%) | 140 (89.2%) | 183 (87.6%) | ||

| Unknown/Unreported | 7 (4.3%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (1.3%) | 6 (2.9%) | ||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Race | ||||||

| American Indian | 2 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | .001 | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.0%) | .042 |

| Asian | 25 (15.3%) | 16 (7.9%) | 13 (8.3%) | 28 (13.4%) | ||

| Black or African American | 7 (4.3%) | 5 (2.5%) | 6 (3.8%) | 6 (2.9%) | ||

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.6%) | 10 (4.9%) | 2 (1.3%) | 9 (4.3%) | ||

| White (Includes Latino) | 115 (70.6%) | 167 (82.3%) | 132 (84.1%) | 150 (71.8%) | ||

| Other | 13 (8.0%) | 5 (2.5%) | 4 (2.5%) | 14 (6.7%) | ||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Protestant | 68 (42.0%) | 81 (40.1%) | .171 | 77 (49.4%) | 72 (34.6%) | .088 |

| Catholic | 47 (29.0%) | 56 (27.7%) | 34 (21.8%) | 69 (33.2%) | ||

| Jewish | 5 (3.1%) | 16 (7.9%) | 12 (7.7%) | 9 (4.3%) | ||

| Muslim | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Buddhist | 7 (4.3%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 7 (3.4%) | ||

| Mormon/LDS | 2 (1.2%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1.9%) | ||

| Jehovah’s Witness | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.0%) | ||

| Seventh Day Adventist | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Other/None | 30 (18.5%) | 44 (21.8%) | 31 (19.9%) | 43 (20.7%) | ||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Income | ||||||

| </= $50K | 39 (23.9%) | 39 (19.2%) | .543 | 33 (21.0%) | 45 (21.5%) | .639 |

| > $50K | 92 (56.4%) | 123 (60.6%) | 96 (61.1%) | 119 (56.9%) | ||

| Declined to state | 32 (19.6%) | 41 (20.2%) | 28 (17.8%) | 45 (21.5%) | ||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Classification of Smoking History | ||||||

| Current Smoker | 14 (8.6%) | 15 (7.4%) | .829 | 13 (8.3%) | 16 (7.7%) | .194 |

| Former Smoker | 63 (38.7%) | 75 (36.9%) | 67 (42.7%) | 71 (34.0%) | ||

| Non-Smoker | 86 (52.8%) | 113 (55.7%) | 77 (49.0%) | 132 (58.4%) | ||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Surgery in past three months | 13 (8.0%) | 18 (8.9%) | .851 | 8 (11.3%) | 5 (5.4%) | .244 |

|

| ||||||

| Pack Years M(SD) | 26.45 (28.11) | 21.78 (28.49) | .126 | 27.15 (25.72) | 26.24 (23.33) | .814 |

|

| ||||||

| Age M(SD) | 57.23 (13.16) | 57.54 (14.31) | .834 | 57.23 (13.16) | 57.54 (14.31) | .834 |

|

| ||||||

| Total # of chronic illnesses M(SD) | 1.36 (1.56) | 1.40 (1.60) | .773 | 1.36 (1.56) | 1.40 (1.60) | .773 |

|

|

|

|

||||

Quality of Life and Psychological Distress

Multivariate analysis of QOL and psychological distress revealed that FCGs in the intervention group had significantly improved QOL in the social well-being domain compared to the usual care group, regardless of disease stage (Table 3). The intervention group had significantly lower psychological distress compared to the usual care group, regardless of disease stage. For spiritual well-being, FCGs in the usual care group had significantly higher QOL compared to FCGs in the intervention group, regardless of disease stage.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis of FCG Psychological Distress and QOL, by Group and Disease Stage

| Outcome | Usual Care (N=157)

|

Intervention (N=197)

|

p-Value

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x̄ | SD | x̄a | x̄ | SD | x̄a | Main1 | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Psychological Distress (Range=0–10; higher=more distress) | Early, I–III | 4.87 | 2.87 | 4.90 | 4.15 | 2.26 | 4.00 | .010 |

| Late, IV | 4.40 | 2.89 | 4.54 | 4.25 | 2.43 | 4.23 | ||

| Total | 4.61 | 2.88 | 4.20 | 2.36 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Physical QOL2 | Early, I–III | 7.07 | 1.76 | 7.08 | 7.27 | 1.88 | 7.07 | .886 |

| Late, IV | 7.06 | 1.78 | 7.22 | 7.26 | 1.62 | 7.27 | ||

| Total | 7.06 | 1.76 | 7.26 | 1.73 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Psychological QOL2 | Early, I–III | 5.38 | 1.69 | 5.43 | 5.79 | 1.28 | 5.39 | .803 |

| Late, IV | 5.13 | 1.57 | 5.35 | 5.34 | 1.43 | 5.44 | ||

| Total | 5.24 | 1.62 | 5.53 | 1.38 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Social QOL2 | Early, I–III | 5.84 | 1.98 | 5.81 | 6.86 | 1.48 | 6.50 | <.001 |

| Late, IV | 6.13 | 1.80 | 6.21 | 6.20 | 1.82 | 6.44 | ||

| Total | 6.00 | 1.89 | 6.48 | 1.71 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Spiritual QOL2 | Early, I–III | 6.67 | 1.79 | 6.56 | 6.55 | 1.41 | 6.39 | .043 |

| Late, IV | 6.43 | 1.81 | 6.53 | 6.14 | 1.70 | 6.25 | ||

| Total | 6.54 | 1.80 | 6.32 | 1.59 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Total QOL2 | Early, I–III | 5.97 | 1.48 | 5.98 | 6.40 | 1.13 | 6.08 | .484 |

| Late, IV | 5.90 | 1.38 | 6.07 | 5.97 | 1.34 | 6.09 | ||

| Total | 5.93 | 1.42 | 6.16 | 1.27 | ||||

Main Effect of Group

Adjusted means

Range = 0–10; higher scores = better QOL

Caregiver Burden and Skills Preparedness

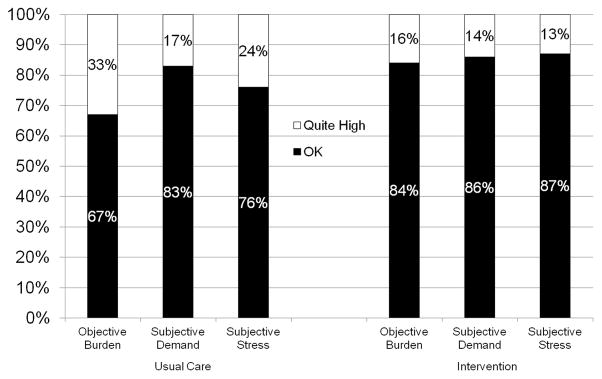

For caregiver burden subscale scores, we found that compared with FCGs in the usual care group, FCGs in the intervention group reported significantly fewer problems with objective burden, or the perceived disruption of the tangible aspects of a FCG’s life (33%; p<.001). The intervention group had significantly fewer FCGs with elevated subjective stress (13%) compared with the usual care group (24%; p=.008). There were no associations between groups for subjective demand, defined as the extent to which the FCG perceives care responsibilities to be overly demanding (p=.376). We did not observe any statistically significant differences between groups or by disease stage for caregiver skills preparedness (Table 4).

Table 4.

FCG Burden and Preparedness

| Outcome | Usual Care (N=157)

|

Intervention (N=197)

|

p-Value

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x̄ | SD | x̄a | x̄ | SD | x̄a | Main1 | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Caregiver Preparedness (Range = 1–5; higher scores = better prepared) | Early, I–III | 3.69 | 0.76 | 3.55 | 3.74 | 0.67 | 3.70 | .091 |

| Late, IV | 3.46 | 0.74 | 3.47 | 3.40 | 0.74 | 3.51 | ||

| Total | 3.56 | 0.76 | 3.55 | 0.73 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| CAREGIVER BURDEN | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Objective Burden2 (Range = 6–30) | Early, I–III | 22.04 | 4.66 | 22.22 | 20.93 | 3.24 | 21.14 | .069 |

| Late, IV | 21.50 | 3.93 | 21.39 | 21.37 | 2.92 | 21.18 | ||

| Total | 21.74 | 4.27 | 21.18 | 3.07 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Subjective Demand2 (Range = 4–20) | Early, I–III | 11.62 | 3.49 | 12.03 | 11.76 | 2.97 | 11.56 | .962 |

| Late, IV | 11.26 | 3.40 | 11.35 | 12.03 | 2.45 | 11.85 | ||

| Total | 11.43 | 3.44 | 11.91 | 2.68 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Subjective Stress2 (Range = 4–20) | Early, I–III | 13.80 | 3.26 | 14.02 | 13.00 | 2.69 | 13.02 | .116 |

| Late, IV | 13.60 | 2.90 | 13.49 | 13.72 | 2.48 | 13.66 | ||

| Total | 13.69 | 3.06 | 13.41 | 2.59 | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

Main Effect of Group

Adjusted means

Higher scores = more burden

Patient and FCG comparison

Post-hoc analysis of patient and FCG outcomes for QOL and psychological distress (Table 5) revealed that patient’s physical and social QOL was significantly higher than FCG QOL in the usual care group (p=.008 and p=.001). FCGs reported higher psychological QOL than patients, regardless of group assignment (p=.033 for usual care; p=.023 for intervention). Patients had significantly higher spiritual QOL than FCGs for the intervention group (p=.028). There were no statistically significant main or interaction effects for psychological distress.

Table 5.

Differences between Patient and FCG Distress and QOL1

| Outcome | Usual Care (N=153)

|

Intervention (N=191)

|

p-Value

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x̄ | SD | x̄a | x̄ | SD | x̄a | Main1 | Interaction2 | ||

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Psychological Distress | FCG | 4.58 | 2.98 | 4.69 | 4.20 | 2.39 | 4.12 | ||

| Pt | 3.09 | 2.70 | 3.15 | 2.29 | 2.19 | 2.25 | .154 | .317 | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Physical QOL | FCG | −.058 | 1.01 | −.016 | .050 | 1.00 | .016 | ||

| Pt | −.327 | 1.18 | −.246 | .135 | .83 | .070 | .286 | .015 | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Social QOL | FCG | −.146 | 1.05 | −.137 | .134 | 0.95 | .129 | ||

| Pt | .084 | .765 | .132 | .148 | .914 | .109 | .059 | .008 | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Psychological QOL | FCG | −.102 | 1.09 | .006 | .089 | .932 | .003 | ||

| Pt | −.183 | 0.98 | −.159 | .181 | 0.98 | .161 | .968 | <.001 | |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Spiritual QOL | FCG | .081 | 1.06 | .091 | −.046 | 0.94 | −.054 | ||

| Pt | −.083 | 0.03 | .002 | .156 | 0.99 | .087 | .670 | .018 | |

QOL transformed to Z scores because FCG and Pt QOL instruments were different, yet contained the same four components.

Main Effect of Group

Interaction between group and stage

Adjusted means

Discussion

Palliative care, as recommended by the IOM, consensus groups, and professional organizations including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), is an integral component of quality cancer care. Over the last decade, several RCTs have tested the effects of early palliative care for cancer patients, including patients with NSCLC. However, few high-profile trials tested the concurrent effects of early palliative care on FCGs, and most interventions were designed only for metastatic disease patients. To our knowledge, this is one of the first large comparative trials that targeted FCGs of patients with all disease stages, and where patients and their FCGs simultaneously participated in the intervention. This approach is recommended by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care25, and acknowledges that both the patient and family unit are affected by a cancer diagnosis. This study also adds to the growing evidence that palliative care integrated with disease-focused care benefits patients and FCGs across disease stages.

The intervention provided a replicable model for elements that should be included in FCG palliative care interventions, including comprehensive FCG QOL assessment, interdisciplinary care recommendations made concurrently for patients and FCGs as a unit, and support of FCG’s QOL needs through education sessions. The tailored approach to educational needs allowed for content delivery endorsed by each specific FCG as high priority. Finally, although self-care is considered an essential content area for interventions, a recent meta-analysis found that many published FCG interventions only included self-care as a secondary focus or as an afterthought.26 Our focus on FCG’s self-care needs as a key intervention component recognizes the importance of self-care in supporting FCG QOL.

Study results revealed that an interdisciplinary approach to palliative care for FCGs resulted in significant improvements in social QOL, psychological distress, and caregiver burden. Other studies have reported similar findings.27,28 We did not observe significant differences by group in FCG’s physical and psychological QOL, and caregiving preparedness. Studies have shown that increases in perceived preparedness may not be observed in the short-term, but over longer time periods.29,30 The short study follow-up (12 weeks) may have resulted in the lack of statistical significance for preparedness, even though the scores improved. Results for spiritual QOL revealed that FCGs in the usual care group reported significantly improved scores compared to the intervention group. In our comparative analysis of patients and FCGs, we also observed different intervention effect on psychological distress and QOL. Although this analysis cannot definitively determine why the intervention did not have a significant impact on spiritual QOL and had differential impact for patients and FCGs, a possible explanation may be an insufficiency in the intervention “dose” and content on supporting FCG’s spiritual QOL and other domains. The patient and FCG outcome variations may be explained by differences in trajectory of distress and QOL. Identification of the appropriate dosing of FCG interventions has been challenging, and future studies should aim to determine an ideal dosing for FCG interventions, and better understanding of the impact of concurrent palliative care on patient and FCG outcomes.26,31

Several study limitations warrant further discussion. The non-randomized design can result in temporal bias related to care pattern changes over time, and may potentially serve as a source of bias for intervention effect. However, the study was conducted in a relatively short period of time (2009–2014) so effects should be minimal. Second, study design did not allow for identifying specific intervention components that resulted in the observed FCG outcomes. This could potentially involve a tremendous amount of resources, a larger sample size, and study design that includes multiple treatment arms to deconstruct intervention components and treatment effects. The inclusion of stages I–III patients as “early” regardless of treatments received may have contributed to the lack of differences when comparing FCGs by patient’s disease stage. Finally, this was a single site trial, and findings may not be generalizable to other disease populations and settings.

In conclusion, this study supports recommendations from the IOM and others for quality cancer care through early, concurrent palliative care that includes FCGs from point of diagnosis to end of life. Future studies are needed to test the long-term effect of interventions on FCG QOL and resource utilizations, replicate the intervention in FCGs for other cancer diagnoses, and assess its generalizability in community settings.

Figure 1.

Caregiver Burden Subscales by Group*

*Percentage of FCGs in each of the subscales who answered “ok” or “quite high”

Acknowledgments

The research described was supported by grant P01 CA136396 (PI: Ferrell) from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or NIH.

References

- 1.Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Apr 10;30(11):1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y, van Ryn M, Jensen RE, Griffin JM, Potosky A, Rowland J. Effects of gender and depressive symptoms on quality of life among colorectal and lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psycho-oncology. 2014 May 16;24(1):95–105. doi: 10.1002/pon.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim Y, Spillers RL, Hall DL. Quality of life of family caregivers 5 years after a relative’s cancer diagnosis: follow-up of the national quality of life survey for caregivers. Psycho-oncology. 2012 Mar;21(3):273–281. doi: 10.1002/pon.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2010 Oct;19(10):1013–1025. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjovall K, Attner B, Lithman T, et al. Sick leave of spouses to cancer patients before and after diagnosis. Acta Oncologica. 2010 May;49(4):467–473. doi: 10.3109/02841861003652566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yabroff KR, Kim Y. Time costs associated with informal caregiving for cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009 Sep 15;115(18 Suppl):4362–4373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mosher CE, Bakas T, Champion VL. Physical health, mental health, and life changes among family caregivers of patients with lung cancer. Oncology nursing forum. 2013 Jan;40(1):53–61. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.53-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis J. The impact of lung cancer on patients and carers. Chronic respiratory disease. 2012 Feb;9(1):39–47. doi: 10.1177/1479972311433577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosher CE, Jaynes HA, Hanna N, Ostroff JS. Distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients: an examination of psychosocial and practical challenges. Support Care Cancer. 2013 Feb;21(2):431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1532-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosher CE, Champion VL, Azzoli CG, et al. Economic and social changes among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2013 Mar;21(3):819–826. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Houtven CH, Ramsey SD, Hornbrook MC, Atienza AA, van Ryn M. Economic burden for informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients. Oncologist. 2010;15(8):883–893. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosher CE, Champion VL, Hanna N, et al. Support service use and interest in support services among distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Psycho-oncology. 2013 Jul;22(7):1549–1556. doi: 10.1002/pon.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant M, Sun V, Fujinami R, et al. Family caregiver burden, skills preparedness, and quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology nursing forum. 2013 Jul;40(4):337–346. doi: 10.1188/13.ONF.337-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujinami R, Sun V, Zachariah F, Uman G, Grant M, Ferrell B. Family caregivers’ distress levels related to quality of life, burden, and preparedness. Psycho-oncology. 2014 May 1; doi: 10.1002/pon.3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Distress Screening. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Institute of Medicine. Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Consensus Project. [Accessed October 15, 2014];Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrell BR, Grant M, Chan J, Ahn C, Ferrell BA. The impact of cancer pain education on family caregivers of elderly patients. Oncology nursing forum. 1995 Sep;22(8):1211–1218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Montgomery R, Stull DB, EF Measurement and the analysis of burden. Research on Aging. 1985;7(1):137–152. doi: 10.1177/0164027585007001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montgomery R, Gonyea J, Hooyman N. Caregiving and the experience of subjective and objective burden. Family Relations. 1985;34(1):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in nursing & health. 1990 Dec;13(6):375–384. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, Tulsky DS, Kaplan E, Bonomi P. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995 Jun;12(3):199–220. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2002 Winter;24(1):49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graves KD, Arnold SM, Love CL, Kirsh KL, Moore PG, Passik SD. Distress screening in a multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic: prevalence and predictors of clinically significant distress. Lung Cancer. 2007 Feb;55(2):215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Consensus Project. [Accessed September 3, 2014];Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010 Sep-Oct;60(5):317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Badr H, Smith CB, Goldstein NE, Gomez JE, Redd WH. Dyadic psychosocial intervention for advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers: Results of a randomized pilot trial. Cancer. 2015 Jan 1;121(1):150–158. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudson P, Trauer T, Kelly B, et al. Reducing the psychological distress of family caregivers of home-based palliative care patients: short-term effects from a randomised controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2013 Sep;22(9):1987–1993. doi: 10.1002/pon.3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schumacher KL, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, Caparro M, Mutale F, Agrawal S. Effects of caregiving demand, mutuality, and preparedness on family caregiver outcomes during cancer treatment. Oncology nursing forum. 2008 Jan;35(1):49–56. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scherbring M. Effect of caregiver perception of preparedness on burden in an oncology population. Oncology nursing forum. 2002 Jul;29(6):E70–76. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.E70-E76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waldron EA, Janke EA, Bechtel CF, Ramirez M, Cohen A. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions to improve cancer caregiver quality of life. Psycho-oncology. 2013 Jun;22(6):1200–1207. doi: 10.1002/pon.3118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]