Abstract

Background

Occupational asbestos exposure has been found to increase lung cancer risk in epidemiological studies.

Methods

We conducted an asbestos exposure-gene interaction analyses among several Caucasian populations who were current or ex-smokers. The discovery phase included 833 Caucasian cases and 739 Caucasian controls, and used a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with gene-asbestos interaction effects. The top ranked SNPs from the discovery phase were replicated within the International Lung and Cancer Consortium (ILCCO). First, in silico replication was conducted in those groups that had GWAS and asbestos exposure data, including 1,548 cases and 1,527 controls. This step was followed by de novo genotyping to replicate the results from the in silico replication, and included 1,539 cases and 1,761 controls. Multiple logistic regression was used to assess the SNP-asbestos exposure interaction effects on lung cancer risk.

Results

We observed significantly increased lung cancer risk among MIRLET7BHG (MIRLET7B host gene located at 22q13.31) polymorphisms rs13053856, rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 heterozygous and homozygous variant allele(s) carriers [p<5×10−7 by likelihood ratio test; df=1]. Among the heterozygous and homozygous variant allele(s) carriers of polymorphisms rs13053856, rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325, each unit increase in the natural log-transformed asbestos exposure score was associated with age-, sex-, smoking status- and center-adjusted ORs of 1.34 (95%CI=1.18–1.51), 1.24 (95%CI=1.14–1.35), 1.28 (95%CI=1.17–1.40), and 1.26 (95%CI=1.15–1.38), respectively for lung cancer risk.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that MIRLET7BHG polymorphisms may be important predictive markers for asbestos exposure-related lung cancer.

Impact

To our knowledge, our study is the first report using a systematic genome-wide analysis in combination with detailed asbestos exposure data and replication to evaluate asbestos-associated lung cancer risk.

Keywords: Lung cancer, asbestos exposure, genome-wide association study, polymorphism

Introduction

Asbestos is a group of fibrous minerals defined as having a length to diameter ratio larger than three to one and was widely used in many products due to its nature of high tensile strength, durability, and heat resistance. Asbestos fibers penetrate deep into the lung and result in a number of respiratory and pleural diseases including lung cancer (1). All forms of asbestos are carcinogenic in humans (2) and are now banned in 52 countries (3). However, asbestos use continues in many other countries (4). Furthermore, asbestos-related diseases are increasing in most areas of the world despite a decrease in world-wide asbestos use (5). Due to a latent period of 30–40 years, a continued global epidemic of asbestos-related diseases is expected (5–7). The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that 107,000 people worldwide die each year from asbestos-related diseases (8).

Lung cancer is the most common asbestos-induced neoplasm. It is estimated that 20,000 asbestos-related lung cancers and 10,000 cases of mesothelioma occur annually across the population of Western Europe, North America, and Asia (9). Epidemiologic studies of occupational cohorts (10, 11) and population-based case-control studies (12, 13) have consistently observed increased lung cancer risk associated with occupational asbestos exposure. Lung cancer incidence increases with increased duration to asbestos exposure (14). Asbestos exposure can induce lung cancer independently, or synergistically with smoking (14) and the interaction between asbestos and smoking has also been found to be approximately multiplicative (15). Adsorption of tobacco carcinogens (e.g., benzo(a)pyrene [BAP]) by asbestos fibers could enhance the carcinogenic potential of the fibers and is a possible mechanism for the observed interaction between asbestos and smoking exposure (16). In addition to exposure factors, genetic polymorphisms are also suspected contributors to cancer development. Some studies have examined interactions between past asbestos exposure and polymorphisms in genes by using either candidate genes approaches (17–21) or using whole-genome association approaches (22).

While these studies have provided some promising results, a systematic genome-wide analysis in combination with detailed asbestos exposure data and replication has yet to be performed to evaluate asbestos-associated lung cancer risk. Therefore, in collaboration with the International Lung and Cancer Consortium (ILCCO) members that have preexisting asbestos exposure measurements and genomic data, we conducted a two-phase approach - discovery and replication- to investigate asbestos exposure and gene-interaction effects in relation to lung cancer risk.

Materials and Methods

Study subjects

Our study included a discovery phase to identify the top associated SNPs and a two-stage approach to replicate the findings. The discovery phase was conducted by using a case-control study based at Mass General Hospital (MGH) in Boston, Massachusetts from 1992 to 2004. Details of the study were described previously (23). Briefly, eligible cases included any person over the age of 18 years with a diagnosis of primary lung cancer that was further confirmed by an MGH lung pathologist. Controls were recruited from the friends or spouses of cancer patients or the friends or spouses of other surgery patients in the same hospital. Potential controls were excluded from participation if they had a diagnosis of any cancer (other than non-melanoma skin cancer). Interviewer-administered questionnaires, a modified version of the standardized American Thoracic Society respiratory questionnaire (24), collected information on demographics, medical history, family history of cancer, smoking history, and a detailed work history, including job titles and tasks. Genome-wide genotype data were first generated using Illumina Human 610-Quad BeadChips and then imputed by MACH (25) against the 1000 Genome Project dataset (http://browser.1000genomes.org/index.html). The Institutional Review Board of MGH and the Human Subjects Committee of the Harvard School of Public Health approved the study.

To confirm the findings, we replicated the analyses in other lung cancer studies. The top ranked SNPs from the discovery phase were replicated within ILCCO with a two-stage replication approach. First, in silico replication was conducted in those groups that have GWAS and asbestos exposure data, including a study conducted at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) (26) and the Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial (CARET), a randomized chemoprevention trial of heavy smokers or asbestos-exposed workers at high risk of lung cancer (27). De novo genotyping was followed for the groups with detailed asbestos exposure information and available DNA samples, involving the ICARE (Investigation of occupational and environmental CAuses of REspiratory cancers) study, a multi-center, population-based case-control study conducted in France by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (INSERM).

The Texas Lung Study included current or former smoking cases of European ancestry and frequency matched ever-smoking controls from Houston, Texas. Cases were newly diagnosed, histologically-confirmed lung cancer patients from MDACC who had not previously received treatment other than surgery. The controls were frequency matched to cases by smoking status, age (with 5 year categories) and sex. Controls were healthy individuals recruited from Kelsey-Seybold Clinic, the largest physician group-practice plan in the Greater Houston area. Genotype data were obtained using Illumina HumanHap3000 v1.1 BeadChips and imputed by MACH (25) using the 1000 Genome Project dataset. Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained from MDACC and the Kelsey-Seybold Clinic.

The CARET study included heavy smokers and asbestos-exposed men who were current or former smokers. The details of the recruitment of the CARET study and the baseline characteristics of the asbestos-exposed subcohort were described previously in Omenn et al. (27) and Cullen et al. (28), respectively. In brief, asbestos-exposed men were eligible for enrollment during the years 1989–1993 if they were between 45 and 69 years of age, were current smokers or had quit smoking within the previous 15 years, and had documentation of exposure. Genotype data were measured by Illumina 379Duo and imputed by MACH using the 1000 Genome Project dataset. All participants signed consent forms that were reviewed by a committee on the protection of human subjects before baseline evaluation.

De novo replication involved lung cancer cases and controls from the ICARE study and were genotyped using OpenArray platform at the Channing Laboratory, Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA). Incident cases were histologically confirmed patients with a primary, malignant tumor and were identified in collaboration with cancer registries. The control participants with no history of previous respiratory cancer were randomly selected from the population of cancer registry areas and were frequency-matched to the cases by gender , age (four categories: less than 40 years, 40–54 years, 55–64 years, >65 years) and area of residence. Details of the study design and study population have been previously described (29). In-person interviews were conducted for all participants to collect baseline and exposure-related information, including lifetime smoking, alcohol-drinking, and a complete occupational history.

Asbestos exposure assessments

In the discovery phase, asbestos exposure was assessed among the participants at MGH in Boston, Massachusetts, using a previously described asbestos exposure index (30). Participants were first asked if they had “ever” been exposed to asbestos. If they answered “yes,” then further exposure information was collected. Individual-level exposure estimates (exposure scores) were calculated based on the source of exposure (both occupational and environmental sources of asbestos exposure), frequency (year-round, seasonal, occasional), and dates of asbestos exposure. Due to the changes in federal regulation of asbestos handling during specific time periods (i.e., pre-1965, 1965–1972, and post-1972), different weights were assigned based on the exposure time period. The weights were originally developed based on asbestos exposure in the New England building construction trades (30). Individuals who reported never being exposed to asbestos were assigned a total asbestos score of zero. A cumulative index (asbestos exposure index) was calculated for each subject by multiplying the number of years of exposure, the weight based on specific years of exposure, and the intensity factor (Supplementary Table 1).

In the in silico replication stage, the asbestos exposure assessment for the Texas Lung Study and CARET study were previously described in Schabath et al. (18) and Barnhart et al. (31), respectively. In brief, participant exposure to asbestos (ever exposure or non-exposure) in the Texas Lung Study was assessed with the following question, Have you handled, used, or been in contact with for at least 8h [hours] a week for a year or more?” In the CARET study, asbestos exposure was assessed based on a lifetime occupational history covering all jobs held for at least one month. Trained coders blinded to disease status coded occupations according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) of the International Labour Organization, 1968 revision, and branches of industry according to the French Nomenclature of Activities (Nomenclature d’activit’es Françaises: NAF) of the National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE), 1999 edition. The CARET study defined high-risk trades as asbestos insulators, sheet metal workers, plumbers/pipefitters, plasterboard workers, boilermakers, shipyard electricians, ship scalers, and ship fitters. Asbestos-related measurements were collected including years in a high-risk trade, years since last asbestos exposure, primary trade, presence of pleural plaques, and ILO grade (i.e., radiographs using ILO standard films to provide evidence for asbestosis in exposed men).

In the de novo replication stage, job exposure matrices (JEMs) were used to assess asbestos exposure in the ICARE study (32). In brief, occupations and industries were classified according to the International Standard Industry Classification (ISIC) and French Nomenclature of Activities, respectively. JEMs were developed using each job’s different historical period, as well as, the probability, frequency, and intensity of asbestos exposure. A cumulative index of exposure was calculated and represents the sum of the product of duration, probability, frequency, and intensity of each exposed job period.

Analytic strategy and SNP selection for replication

We restricted the analysis to current and ex-smoking Caucasians. The discovery phase included 833 Caucasian cases and 739 Caucasian controls from the Harvard Lung Cancer Study. Quality control for the SNP data was applied to the genetic data from all stages including the discovery and replication stages. SNPs were excluded from further analysis if: (1) p<1×10−6 for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium among controls; (2) the minor allele frequency (MAF) was <1%; and (3) the call rate was <90%.

The threshold for gene-environment interaction studies from GWAS was yet to be determined due to the few large studies with replication to assess a threshold standard (33). We used the discovery phase to prioritize SNPs to determine if interactions are considerable and worthy for further replication. The top associated SNPs were first identified by the discovery phase if the asbestos-gene interaction terms where p<5×10−5 as determined by likelihood-ratio tests (LRTs) and if the SNPs passed quality control. The identified top ranked SNPs were then replicated by a two-stage approach, including in silico replication among those groups that had both GWAS and asbestos exposure data and de novo genotyping among the groups with available DNA samples and with detailed asbestos exposure information. The asbestos-gene interaction terms p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant during the replication stage. The SNPs that were statistically significant during the in silico replication were then de novo genotyped. The in silico replication included a total of 1,548 cases and 1,527 controls (1,154 cases and 1,137 controls from the Texas Lung Study and 394 cases and 390 controls from the CARET study). Finally, de novo genotyping was conducted among 1,412 cases and 1,119 controls from the ICARE study.

The identified SNPs were subject to in silico functional predictions and annotations using UCSC Genome browser (34, 35), SNPinfo (36), SNPnexus (37, 38), RegulomeDB (39) and HaploReg (40)

Statistical analysis

Genotype frequencies among controls were tested for departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium by the Pearson χ2 test (df=1). The selected participants’ characteristics were evaluated using χ2 and t tests as appropriate. Likelihood-ratio tests were used to determine whether the asbestos-gene interaction terms departed from a multiplicative interaction model. Multiple logistic regression with additive genetic effect models were used to assess the associations between lung cancer risk and the interaction effects of asbestos exposure and genetic polymorphism using PLINK, version 1.07 (39). Descriptive statistics were analyzed using SAS® software version 9.3 (Cary, North Carolina) and R version 3.1.1 (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org/). The effects of asbestos exposures were evaluated by dichotomized exposure status (i.e., ever or never exposed) among the Texas Lung Study and by continuous asbestos exposure measurement scores among the Harvard Lung Cancer Study, the CARET study, and the ICARE study. Adjustment for several potential confounders such as age, sex, smoking status (current or quit within one year; ex-smoker), study center (random effects, including Harvard Lung Cancer Study, Texas Lung Study, CARET study, and the ICARE study) and population stratification were used in the mixed-effects multiple logistic regression models. The effects of population stratification were adjusted by including the first four principal components from the EIGENSTRAT (40) analysis among the groups with genome-wide data available (i.e., the Harvard Lung Cancer Study, the Texas Lung Study, and the CARET study). Pooled data was created among the groups with continuous asbestos exposure measurement scores (i.e., the Harvard Lung Cancer Study, the CARET study, and the ICARE study). Stratified analyses by dominant genetic effects, gender, and histology (the two dominant disease subtypes, adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma cases) were conducted among the pooled data to estimate the asbestos exposure odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) with lung cancer risk for the replicated SNPs.

Results

The distributions of selected characteristics among study subjects of each study are summarized in Table 1. The mean ages of the study participants from the four studies were between 58 and 72 years old. The study participants in the CARET study were older while those in the ICARE study were younger. Most of the groups in these studies included more males than females, especially the ICARE study. The CARET study had more current smokers (78%) while other studies had slightly more ex-smokers. Cases had smoked more pack-years than the controls in all study groups. The asbestos exposure information included categorical (ever or never exposed to asbestos) for all study groups, and a continuous asbestos exposure score was measured in the Harvard Lung Cancer Study, the CARET study, and the ICARE study. The Texas Lung Study did not calculate a continuous asbestos exposure measurement. In each of the studies, a greater proportion of individuals in the ever exposed to asbestos group were cases. The ICARE study had the greatest proportion of the asbestos exposed participants (62% of the lung cancer cases and 56% of the controls) while the Texas Lung Study had the fewest exposed participants (14% of the lung cancer cases and 9% of the controls). Among the study groups with continuous asbestos measurement exposure scores, the asbestos exposure levels showed the most significant differences between cases and controls among participants in the ICARE study (p <0.0001).

Table 1.

Distribution of study subjects of the Harvard Lung Cancer Study, the CARET study, the Texas Lung Study, and the ICARE study by demographic and risk factors

| Harvard Lung Cancer Study |

CARETa |

Texas Lung Study |

ICAREb |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Case (n=833) |

Control (n=739) |

p-value | Case (n=394) |

Control (n=390) |

p-value | Case (n=1154) |

Control (n=1137) |

p-value | Case (n=1412) |

Control (n=1119) |

p-value |

| Age (years)c | 65.5 (10.2) | 59.3 (11.5) | <0.0001 | 70.3 (5.3) | 71.6 (5.3) | 0.03 | 62.1 (10.8) | 62.1 (8.9) | 0.013 | 59.6 (9.3) | 58.1 (9.8) | 0.0002 |

| Sex | 0.01 | 0.86 | 0.87 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Male (%) | 396 (47.5) | 397 (53.7) | 252 (64.0) | 247 (63.3) | 658 (57.0) | 644 (56.6) | 1183 (83.8) | 1011 (90.3) | ||||

| Female (%) | 437 (52.5) | 342 (46.3) | 142 (36.0) | 143 (36.7) | 496 (43.0) | 493 (43.4) | 229 (18.2) | 108 (9.7) | ||||

| Smoking | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.01 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Current smokingd | 366 (43.9) | 232 (31.4) | 306 (77.7) | 297 (76.2) | 550 (47.7) | 481 (42.3) | 628 (44.5) | 278 (24.8) | ||||

| Pack-yearsc | 55 (33.9) | 29.7 (26.5) | <0.0001 | 53.1 (21.5) | 52.0 (22.5) | 0.85 | 51.5 (31.4) | 44.6 (30.2) | 38.9 (23) | 18.9 (17.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Asbestos Exposure | 0.049 | 0.73 | 0.002 | 0.0019 | ||||||||

| Never | 650 (78.0) | 606 (82.0) | 333 (84.5) | 333 (85.4) | 990 (86.2) | 1031 (90.8) | 536 (38.0) | 493 (44.1) | ||||

| Ever | 183 (22.0) | 133 (18.0) | 61 (15.5) | 57 (14.6) | 159 (13.8) | 105 (9.2) | 876 (62.0) | 626 (55.9) | ||||

| Asbestos Exposure | ||||||||||||

| Scorece | 0.6 (1.4) | 0.5 (1.2) | 0.016 | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.3 | NA | NA | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.9) | <0.0001 | |

| Histology | ||||||||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 406 (48.7) | 105 (26.7) | 597 (51.7) | 536 (38.0) | ||||||||

| Squamous | 192 (23.1) | 70 (17.8) | 309 (26.8) | 452 (32.0) | ||||||||

| Small cell carcinoma | 85 (10.2) | 52 (13.2) | 0 (0.0) | 208 (14.7) | ||||||||

| Other | 150 (18.0) | 167 (42.3) | 248 (21.5) | 216 (15.3) | ||||||||

CARET, Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial

ICARE, Investigation of occupational and environmental CAuses of REspiratory cancers

Mean(SD)

Current or quit within the last year

log-transformed

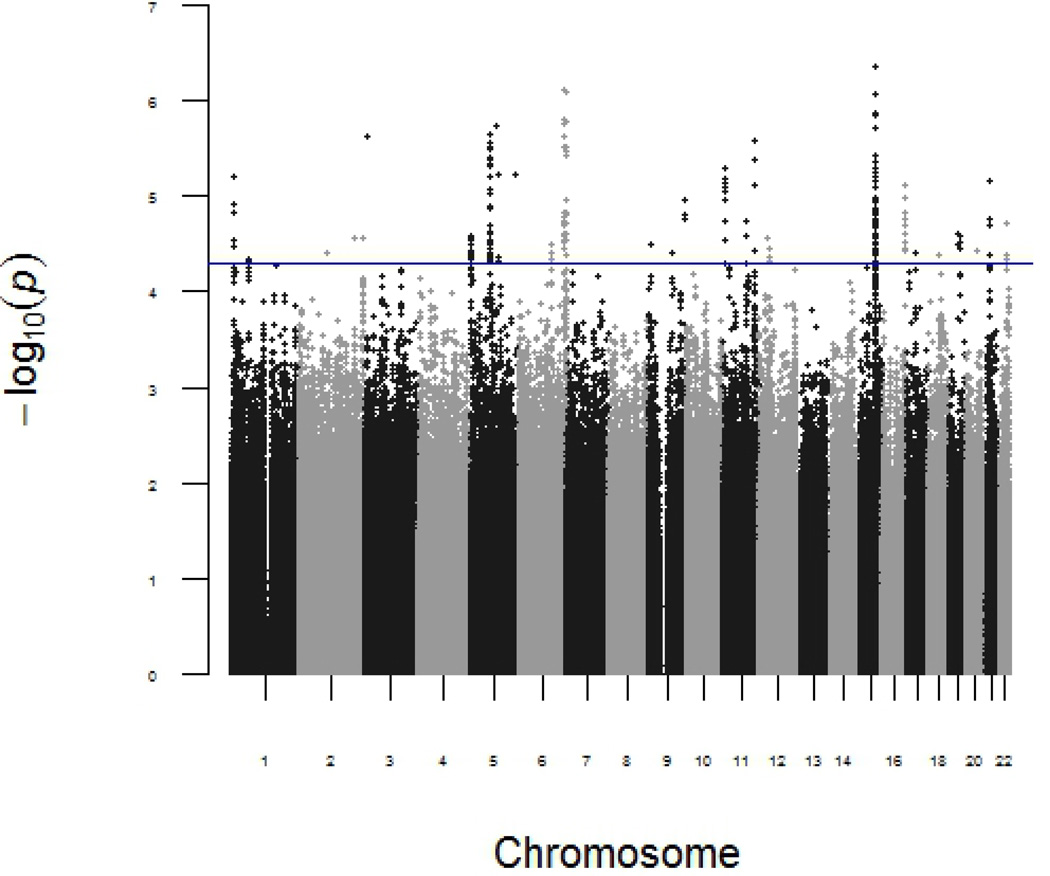

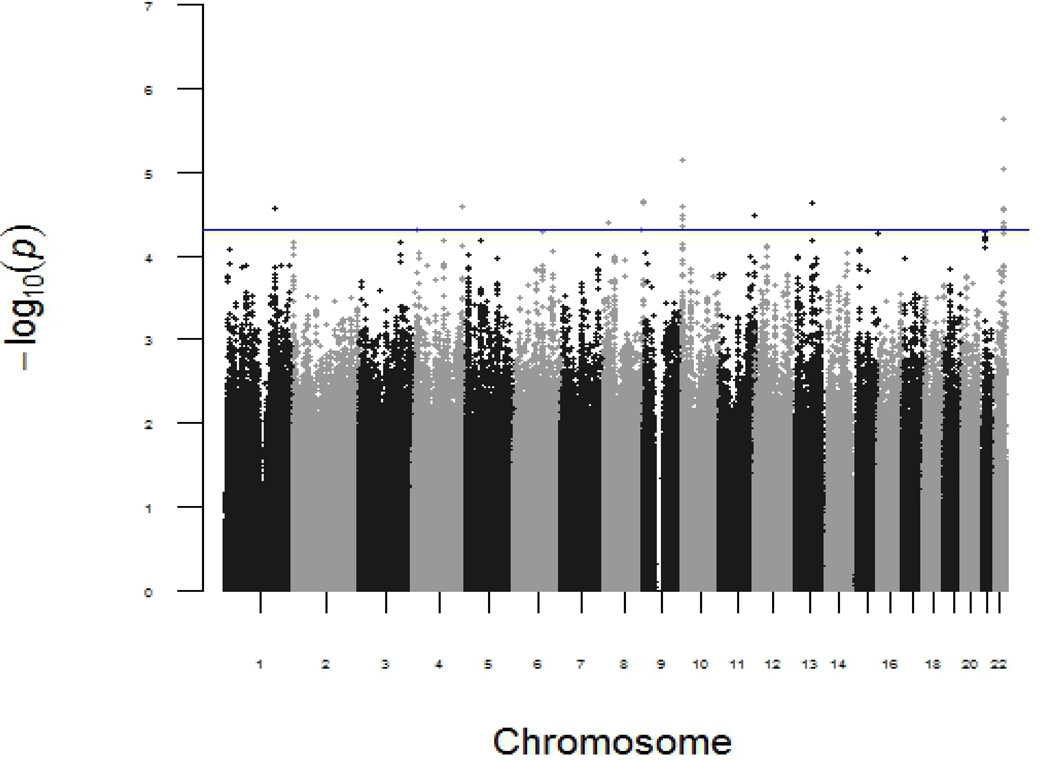

In the discovery phase, the p-values for the independent SNP effects and the interaction between each of the SNPs and asbestos exposure in the discovery phase are shown in Manhattan plots (Figure 1 and 2, respectively). The top SNP with independent main effect on lung cancer risk is rs17486278 in CHRNA5, (p=4 × 10−7). A total of 4,649,540 SNPs passed quality control and 31 SNPs were identified by LRTs with asbestos-gene interaction terms (p<5 ×10−5) in the discovery phase. These 31 top associated SNPs were in silico replicated in the CARET study and the Texas Lung Study. Four of the polymorphisms (i.e., rs13053856, rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325) of MIRLET7BHG (MIRLET7B host gene) located at 22q13.31, showed asbestos-gene interaction terms (p<0.05) in the CARET study. These four SNPs were in complete linkage disequilibrium (LD) (D’=1) in the CARET study. In the Texas Lung Study, only rs13053856, the polymorphism with the smallest p-value in the discovery phase, was identified with the interaction terms (p=0.03) (Table 2). De novo genotyping was conducted for the four SNPs that were successfully replicated in the CARET study. The genotyping failed for the polymorphism rs13053856 in the ICARE study, however the three remaining polymorphisms were replicated with interaction terms p<0.05 (rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325). The summary of the in silico functional predictions and annotations of these identified SNPs are summarized in Table 3. The polymorphisms rs13053856, rs11703832, and rs12170325 lie at strong enhancers in several cell lines, including the lung fibroblasts NHLK, mammary epithelial HMEC, epidermal keratinocyte NHEK, and skeletal muscle myoblast HSMM, and are likely to affect binding, histone marks, and DNAse sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Genome-wide genetic association and lung cancer risk in discovery stage. P-value was calculated by an additive genetic model in the multiple logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex, smoking status and population stratification

Figure 2.

Genome-wide gene-asbestos exposure interactions and lung cancer risk in discovery stage. P-value was calculated by the interaction term of an additive genetic model and asbestos exposure in the multiple logistic regression model adjusted for age, sex, smoking status and population stratification

Table 2.

Top associated findings of asbestos-gene interaction terms determined by likelihood-ratio tests (LRT) replicated in in silico

| SNP |

Cytogenetic region |

Gene | MAF1 | Regression coefficient1 |

P-value1 | MAF2 | Regression coefficient2 |

P-value2 | MAF3 | Regression coefficient3 |

P-value3 | MAF4 | Regression coefficient4 |

P-value4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs13053856 | 22q13.31 | MIRNA7BHG | 0.26 | 1.75 | 2.31E-06 | 0.25 | 0.33 | 1.09E-02 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 0.0314 | - | - | |

| rs11090910 | 0.26 | 1.49 | 9.06E-06 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 2.14E-02 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 1.21E-02 | ||

| rs11703832 | 0.20 | 1.56 | 2.88E-05 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 1.50E-02 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 2.60E-03 | ||

| rs12170325 | 0.20 | 1.56 | 2.88E-05 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 1.50E-02 | 0.22 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 3.39E-02 |

Harvard Lung Cancer Study

the CARET study

Texas Lung Study

the ICARE study replication

Table 3.

Results from the in silico functional prediction

| SNP | Allele | Gene symbol | Predicted function |

Splice distance |

TFBS | Promoter histone marks |

Enhancer histone marks |

Proteins bound |

Motifs changed |

RegulomeDBa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs13053856 | A/G | MIRLET7BHG | Intronic | 753 | NHLF, HMEC, NHEK, HSMM |

ERalpha-a, INSM1 |

2b | |||

| rs11090910 | C/T | MIRLET7BHG | 3’ Downstream | Yes | H1, HSMM | 5 | ||||

| MIRLET7A3 | 5’ Upstream | |||||||||

| MIR4763 | 5’ Upstream | |||||||||

| MIRLET7B | 5’ Upstream | |||||||||

| rs11703832 | C/T | MIRLET7BHG | Intronic | 980 | Yes | HepG2 | NHLF, NHEK, HMEC, HSMM, HepG2 |

7 altered motifs |

4 | |

| rs12170325 | C/T | MIRLET7BHG | 3’ Downstream | 2277 | HepG2 | HepG2, NHLF, HMEC, NHEK, HSMM, H1 |

TAF1 | Hsf, Mef2 | 2b |

RegulomeDB scores: 1a: eQTL + TF binding + matched TF motif + matched DNase Footprint + DNase peak; 1b: eQTL + TF binding + any motif + DNase Footprint + DNase peak; 1c: eQTL + TF binding + matched TF motif + DNase peak; 1d: eQTL + TF binding + any motif + DNase peak;1e: eQTL + TF binding + matched TF motif;1f: eQTL + TF binding / DNase peak; 2a: TF binding + matched TF motif + matched DNase Footprint + DNase peak; 2b: TF binding + any motif + DNase Footprint + DNase peak; 2c, TF binding + matched TF motif + DNase peak; 3a: TF binding+ any motif + DNase peak; 3b: TF binding + matched TF motif; 4: TF binding + DNase peak; 5: TF binding or DNase peak; 6: other

To garner sufficient power, stratified analyses of these four SNPs (rs13053856, rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325) were conducted among a pooled dataset. In the pooled dataset, each unit increase in the natural log-transformed asbestos exposure score was associated with an age-, sex-, smoking status- and center-adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) of 1.10 (95% CI = 1.05–1.16; p=1.42 × 10−4) in association with lung cancer risk and aORs of 1.07 (95% CI = 1.01–1.14; p=3.28 × 10−2) and 1.19 (95% CI = 1.11–1.28; p=6.39 × 10−7) in association with lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell lung cancer risk when stratified by disease subtype (Table 4). Without considering the genetic effects, the significant asbestos exposure effects were observed in men but not in women (Table 4). When stratified by MIRLET7BHG genotypes, asbestos exposure was significantly associated with lung cancer risk among the subjects with MIRLET7BHG variant allele(s) (Table 5). Each unit increase in the natural log-transformed score was associated with an aOR of 1.34 (95% CI = 1.18–1.51) in subjects carrying rs13053856 heterozygous and homozygous variant alleles, and aOR of 0.94 (95% CI = 0.86–1.03) in subjects carrying homozygous wildtype alleles. Significantly increased risks were also observed among rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 heterozygous and homozygous variant allele(s) carriers and null associations among participants carrying homozygous wildtype alleles. When stratified by disease subtypes, significant interactions were observed between asbestos exposure and the rs13053856 polymorphism in association with lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell lung cancer risk (by LRTs, p= 1.06 × 10−3 and 8.36 × 10−5, respectively). Asbestos exposure among the heterozygous and homozygous variant allele(s) carriers was associated with higher risk for adenocarcinoma and squamous cell lung cancer (Table 3). Among the heterozygous and homozygous variant allele(s) carriers of polymorphism rs13053856, each unit increase in the natural log-transformed score was associated with an aOR of 1.35 (95% CI = 1.15–1.58) and 1.48 (95% CI = 1.22–1.80), respectively, for lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell lung cancer risk. Null associations for lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell lung cancer risk were observed among rs13053856 homozygous wildtype carriers. There were no statistically significant interactions between asbestos exposure and the polymorphisms rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 in association with lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell lung cancer risk.

Table 4.

Distribution and adjusted odds ratios of asbestos exposure among women and men for the risk of lung cancer from a pooled dataset

| Gender | Exposed subjects (%) | All Lung Cancer | Lung Adenocarcinoma | Lung Squamous | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Lung Cancer Case | Lung Adenocarcinoma | Lung Squamous | Control | |||||||||||

| n (%) | Asbestos Exposure Scorea |

n (%) | Asbestos Exposure Scorea |

n (%) | Asbestos Exposure Scorea |

n (%) | Asbestos Exposure Scorea |

OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value | |

| Women and Men | 1120 (42.2) | 0.64 (1.26) | 414 (39.5) | 0.60 (1.25) | 369 (51.7) | 0.80 (1.35) | 816 (36.3) | 0.47 (1.07) | 1.10 (1.05–1.16)b | 1.42E-04 | 1.07 (1.01–1.14)b | 3.28E-02 | 1.19 (1.11–1.28)b | 6.39E-07 |

| Women | 194 (24.0) | 0.59 (1.43) | 89 (24.5) | 0.59 (1.11) | 53 (27.2) | 0.78 (1.22) | 122 (20.6) | 0.46 (0.97) | 1.06 (0.97–1.15) c | 1.98E-01 | 1.04 (0.94–1.16) c | 4.05E-01 | 1.09 (0.97–1.23) c | 1.44E-01 |

| Men | 926 (50.6) | 0.67 (1.18) | 325 (47.6) | 0.61 (1.47) | 316 (60.9) | 0.83 (1.66) | 694 (41.9) | 0.51 (1.31) | 1.16 (1.09–1.24)c | 6.98E-06 | 1.15 (1.06–1.26)c | 1.35E-03 | 1.24 (1.13–1.36)c | 4.15E-06 |

Mean(SD) of log-transformed exposure score

Odds ratios and confidence intervals were calculated for one unit of increase in the log-transformed asbestos exposure score by mixed-effects logistic regression adjusted for age, gender, smoking status, and center.

Odds ratios and confidence intervals were calculated for one unit of increase in the log-transformed asbestos exposure score by mixed-effects logistic regression adjusted for age, smoking status, and center.

Table 5.

Distribution and adjusted odds ratios of asbestos exposure stratified by MIRLET7BHG genotypes for the risk of lung cancer from a pooled dataset

| SNP | Women and Men |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed subjects (%) |

All Lung Cancer |

Lung Adenocarcinoma |

Lung Squamous |

|||||||

| All Lung Cancer Case |

Lung Adenocarcinoma |

Lung Squamous |

Control | OR (95%CI)a | p-value | OR (95%CI)a | p-value | OR (95%CI)a | p-value | |

| rs13053856 GG | 112 (17.8) | 46 (19.7) | 28 (19.7) | 114 (19.8) | 0.94 (0.86–1.03) | 1.74E-01 | 0.94 (0.83–1.06) | 3.26E-01 | 0.96 (0.83–1.11) | 5.83E-01 |

| GA+AA | 115 (23.1) | 47 (22.9) | 26 (33.3) | 63 (13.9) | 1.34 (1.18–1.51) | 3.13E-06 | 1.35 (1.15–1.58) | 1.91E-04 | 1.48 (1.22–1.80) | 6.74E-05 |

| rs11090910 TT | 527 (39.6) | 208 (39.3) | 170 (48.7) | 429 (37.0) | 1.05 (0.98–1.12) | 1.85E-01 | 1.02 (0.93–1.12) | 6.32E-01 | 1.14 (1.04–1.27) | 4.75E-03 |

| TC+CC | 485 (44.8) | 163 (40.5) | 165 (56.5) | 324 (35.3) | 1.24 (1.14–1.35) | 3.00E-07 | 1.18 (1.06–1.31) | 2.48E-03 | 1.31 (1.17–1.48) | 3.46E-06 |

| rs11703832 CC | 632 (39.6) | 254 (39.6) | 184 (45.7) | 497 (36.1) | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 8.28E-02 | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 5.07E-01 | 1.11 (1.01–1.22) | 2.35E-02 |

| CT+TT | 397 (44.4) | 126 (40.1) | 138 (59.7) | 263 (34.2) | 1.28 (1.17–1.40) | 1.41E-07 | 1.20 (1.07–1.35) | 1.93E-03 | 1.42 (1.25–1.61) | 3.15E-08 |

| rs12170325 CC | 643 (39.9) | 259 (39.5) | 188 (46.5) | 505 (36.3) | 1.06 (0.99–1.14) | 6.69E-02 | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) | 3.94E-01 | 1.11 (1.01–1.22) | 2.54E-02 |

| CT+TT | 410 (44.5) | 129 (40.7) | 151 (60.2) | 271 (34.4) | 1.26 (1.15–1.38) | 2.88E-07 | 1.20 (1.07–1.34) | 2.02E-03 | 1.38 (1.23–1.56) | 1.14E-07 |

| SNP | Women |

Men |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Lung Cancer |

Lung Adenocarcinoma |

Lung Squamous |

All Lung Cancer |

Lung Adenocarcinoma |

Lung Squamous |

|||||||

| OR (95%CI)b | p-value | OR (95%CI)b | p-value | OR (95%CI)b | p-value | OR (95%CI)b | p-value | OR (95%CI)b | p-value | OR (95%CI)b | p-value | |

| rs13053856 GG | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 1.16E-01 | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | 1.77E-01 | 0.94 (0.80–1.11) | 4.75E-01 | 0.92 (0.78–1.09) | 3.41E-01 | 1.10 (0.85–1.42) | 4.75E-01 | 0.83 (0.57–1.20) | 3.14E-01 |

| GA+AA | 1.37 (1.16–1.62) | 2.55E-04 | 1.32 (1.10–1.59) | 3.23E-03 | 1.39 (1.11–1.73) | 3.51E-03 | 1.05 (0.86–1.28) | 6.33E-01 | 1.36 (0.99–1.86) | 5.74E-02 | 1.69 (1.12–2.55) | 1.21E-02 |

| rs11090910 TT | 0.92 (0.82–1.03 | 1.32E-01 | 0.92 (0.80–1.06) | 2.69E-01 | 0.97 (0.83–1.14) | 7.21E-01 | 1.17 (1.06–1.28) | 1.32E-03 | 1.21 (1.07–1.37) | 2.55E-03 | 1.26 (1.10–1.43) | 4.79E-04 |

| TC+CC | 1.31 (1.13–1.52) | 4.50E-04 | 1.27 (1.07–1.50) | 5.19E-03 | 1.34 (1.11–1.63) | 2.99E-03 | 1.18 (1.06–1.31) | 1.63E-03 | 1.12 (0.97–1.29) | 1.16E-01 | 1.24 (1.07–1.44) | 3.88E-03 |

| rs11703832 CC | 0.95 (0.85–1.05) | 2.98E-01 | 0.94 (0.82–1.07) | 3.61E-01 | 0.96 (0.83–1.12) | 6.14E-01 | 1.15 (1.06–1.26) | 1.42E-03 | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | 6.70E-03 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 3.80E-03 |

| CT+TT | 1.31 (1.11–1.54) | 1.16E-03 | 1.27 (1.07–1.52) | 7.92E-03 | 1.40 (1.13–1.72) | 1.64E-03 | 1.19 (1.07–1.34) | 1.88E-03 | 1.14 (0.97–1.33) | 1.09E-01 | 1.36 (1.17–1.59) | 9.45E-05 |

| rs12170325 CC | 0.95 (0.85–1.05) | 3.02E-01 | 0.94 (0.82–1.07) | 3.58E-01 | 0.96 (0.83–1.12) | 6.36E-01 | 1.16 (1.06–1.26) | 1.41E-03 | 1.18 (1.06–1.32) | 3.23E-03 | 1.20 (1.06–1.36) | 4.97E-03 |

| CT+TT | 1.31 (1.11–1.54) | 1.20E-03 | 1.28 (1.08–1.52) | 7.35E-03 | 1.40 (1.14–1.72) | 1.51E-03 | 1.18 (1.06–1.31) | 3.25E-03 | 1.13 (0.97–1.31) | 1.26E-01 | 1.31 (1.13–1.51) | 3.90E-04 |

Odds ratios and confidence intervals were calculated for one unit of increase in the log-transformed asbestos exposure score by mixed-effects logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, and center.

Odds ratios and confidence intervals were calculated for one unit of increase in the log-transformed asbestos exposure score by mixed-effects logistic regression adjusted for age, smoking status, and center.

When stratified by gender, these interaction effects were more evident in women. Among women, significant interactions were observed between asbestos exposure and the polymorphisms rs13053856, rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 (by Likelihood Ratio Tests, (LRT) p=2.01 × 10−4, 4.94 × 10−4, 1.54 × 10−3, 1.80 × 10−3 respectively). Each unit increase in the natural log-transformed score was associated with an aOR of 1.37 (95% CI =1.16–1.62) in women carrying rs13053856 heterozygous and homozygous variant alleles, and aOR of 0.91 (95% CI = 0.81–1.02) in women carrying homozygous wildtype alleles. Significantly increased lung cancer risks were also observed in women carrying rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 heterozygous and homozygous variant allele(s) and null associations among women carrying homozygous wildtype alleles. When stratified by disease subtypes, significant interactions were observed among women between asbestos exposure and the polymorphisms rs13053856, rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 in association with lung adenocarcinoma (by LRTs, p = 1.01 × 10−3, 4.68 × 10−3, 3.98 × 10−3, and 3.13 × 10−3 respectively) and squamous cell lung cancer risk (by LRTs, p= 6.45 × 10−3, 3.91 × 10−2, 1.04 × 10−2, and 1.32 × 10−2 respectively). Significant lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell lung cancer risk in association with asbestos exposure effects were observed in women carrying rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 heterozygous and homozygous variant allele(s) and null associations among women carrying homozygous wildtype alleles (Table 4). Significant interaction was observed among women who were ex-smokers or current smokers (Supplementary Table 4). Among women who were ex-smokers, significant interaction was observed between asbestos exposure and the polymorphisms rs13053856, rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 (by LRTs, p= 2.90 × 10−3, 1.46 × 10−2, 3.28 × 10−2, and 4.69 × 10−2 respectively). Significant interaction was observed between asbestos exposure and the polymorphism rs13053856 (by LRT, p= 2.06 × 10−2) among women who were current smokers.

There were no statistically significant interactions observed among men in association with either all lung cancer or lung cancer disease subtypes.

Discussions

We conducted a genome-wide interaction study of asbestos exposure and lung cancer risk among Caucasian populations who were current or ex-smokers. After replication, our findings suggest that polymorphisms of MIRLET7BHG (MIRLET7B host gene) are associated with asbestos-related lung cancer risk.

MIRLET7BHG that hosts the MIRLET7 genes are located at 22q13.31. The region with microRNA (miRNAs) MIRLET7A3, MIR4763, and MIRLET7B clustered within approximately 900 bps has been reported to be commonly lost in asbestos exposure-related disease (41–43). Most miRNAs, the small non-protein-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression (44, 45), have highly correlated expression patterns with neighboring miRNAs and host genes (46). In silico functional predictions and annotations using UCSC Genome browser (47), SNPinfo (48), SNPnexus (35, 36), RegulomeDB (37) and HaploReg (38) suggest that rs13053856, rs11703832, and rs12170325 lie at strong enhancers in the lung fibroblasts cell line NHLK and are likely to affect binding. Silencing MIRLET7BHG has been suggested to be related to tumor invasion and proliferation in cancer cells (39). Let-7 is expressed in normal adult lung tissue (40, 49) but is poorly expressed in lung cancer cell lines and lung cancer tissues for patients with adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (50–52). Several studies suggest let-7 functions as tumor suppressors, especially in lung cancer. Administration of let-7 has been found to block the growth of cultured lung cancer cells and prevent the onset of tumor formation in mouse models (53–55). Down-regulation of let-7 in lung cancers has been related to poor prognosis (51, 56). Let-7 down-regulates multiple oncogenes (i.e., RAS, MYC, HMGA2), promoters of cell cycle progression (i.e., CDC25A, CDK6, and Cyclin D2) (51–54, 57–59), and cytokines with anti-inflammatory properties (i.e., IL-10) (60). In the early response to mineral particles, IL-10, as well as the other anti-inflammatory cytokines, are able to affect the pulmonary response to particles (61). One study has shown that IL-10 knockout mice were relatively protected from silica-induced fibrosis (62). There is considerable evidence that asbestos-initiated chronic oxidative stress contributes to carcinogenesis and fibrosis by promoting oxidative DNA damage and regulating redox signaling pathways in exposed cells (63). Reduced levels of let-7 may therefore provide a microenvironment favoring cancer development and progression especially during asbestos exposure.

The gene-asbestos interaction effects by smoking status were evaluated. Significant gene-asbestos interaction effects were observed among both current and ex-smokers (Supplementary Table 3). Smoking is a potential confounder for asbestos and most people with asbestos exposure are exposed to smoking simultaneously. Gene-smoking interaction effects by asbestos status were also tested to assess if there was gene-smoking interaction effects in the absence of asbestos exposure. We observed gene-smoking interaction effects only among asbestos exposed subjects (rs12170325 p=0.03 by LRT; df=1) and a null association in the absence of asbestos exposure. However, after correction for multiple comparisons, this result was not statistically significant. Persons who are exposed to smoking and asbestos simultaneously show more severe deleterious effects of their cells (64, 65). Our data suggests the potential roles of asbestos exposure and MIRLET7BHG polymorphisms in the context of smoking in lung cancer risk.

Female gender has been found to be a positive prognostic factor regardless of lung cancer type, stage and therapy (66–68). The gender-specific effects may be due to a variety of mechanisms, ranging from different behavior between genders such as smoking habits, gender-specific lifestyle, sex hormones, as well as genetic and epigenetic differences (69). In our study, women with variant allele(s) were associated with increased lung cancer risk while asbestos exposure were associated with null associations among homozygous wildtype women carriers (Table 5). Among men, asbestos exposure associated lung cancer risk was observed among variant as well as wildtype carriers of rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 polymorphisms. Significant MIRLET7BHG gene-asbestos interaction effects among women remained after stratification by smoking status (i.e. ex-smokers or current smokers; Supplementary Table 4). Further gender specific mechanistic effects such as different miRNAs expressions between women and men may affect disease pathogenesis (reviewed in (70)). Expression frequency and regulation of let-7a has been found to be higher in women than in men in familial breast cancer carcinogenesis (71). However, there were fewer women with occupational asbestos exposure in our study (Table 4) therefore potentially destabilizing estimates. Additional studies are needed to identify if the gender-specific differences exist and the functionality of the genetic variants.

Previous candidate gene studies have mainly focused on the genes involved in xenobiotic and oxidative metabolism (reviewed in (72)) and these studies were limited by small size of study populations and did not identify statistically significant interaction effects. However, Wei et al. (73) used whole-genome association approaches in the Texas Lung Study. Wei et. al. (74) reported that polymorphism rs13383928 was the most significant asbestos-gene interaction term (df=1) with a p-value of 2.17×10−6. Though, the polymorphism rs13383928 was not replicated in the Harvard Lung Study (discovery phase) or the CARET study (in silico replication stage). Measurements of environmental exposures remain a constant challenge in epidemiologic studies, especially when different study groups are used to replicate findings. Despite that different scoring methods were used for asbestos exposure assessment, the interaction effects of MIRLET7BHG polymorphisms and asbestos exposure remained between our collaborative study groups. However, we note it is likely that there are other polymorphisms we were not able to replicate due to the differing exposure assessment methods and variability within study participants and exposure status.

We used a genome-wide association study (GWAS) to identify top SNPs with gene-environment interaction effects and our top SNPs from the GWAS were validated in independent samples. Our study observed significantly increased risks among MIRLET7BHG polymorphisms rs13053856, rs11090910, rs11703832, and rs12170325 heterozygous and homozygous variant allele(s) carriers. In contrast, null associations were observed among subjects carrying homozygous wildtype alleles. The observed associations in our study provide additional molecular epidemiologic insight into asbestos-related lung cancer risk.

Asbestos exposure will remain a ubiquitous global issue because over 70% of asbestos produced worldwide is used in Asia and Eastern Europe. (22). Therefore we firmly believe that our observed associations should be confirmed in another large, independent study as well as further studies in different populations of individuals with more variation in genetics and exposure. Moreover, additional investigation of the functional genetic variants, or epigenetic modification, linked to the polymorphisms in MIRLET7BHG gene are also needed to confirm the genetic effects of MIRLET7BHG polymorphisms on asbestos exposure-related lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Drs. Margaret Spitz, Xifeng Wu and Sheng Wei for providing data from the University of Texas MD Anderson Texas Lung Study.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA092824, CA090578, CA074386, and ES00002 to D.C.C./ Harvard studies).

Sponsors had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Mossman BT, Kamp DW, Weitzman SA. Mechanisms of carcinogenesis and clinical features of asbestos-associated cancers. Cancer Invest. 1996;14:466–480. doi: 10.3109/07357909609018904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Overall evaluations of carcinogenicity: Qn updating of IARC monographs volumes 1–42. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. 1987;(Suppl 7) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kazan-Allen L. The international ban asbestos secretariat. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2000;6:164. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2000.6.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramazzini C. Asbestos is still with us: Repeat call for a universal ban. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54:168–173. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institue of Medicine. Asbestos: Selected Cancers. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaDou J. The asbestos cancer epidemic. Environ Health Persp. 2004;112:285–290. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stayner L, Welch LS, Lemen R. The worldwide pandemic of asbestos-related diseases. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2013;34:205–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization.(WHO) [Date Accessed: July 2010];Asbestos: elimination of asbestos-related diseases. Fact sheet No. 343. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs343/en/

- 9.Tossavainen A. International expert meeting on new advances in the radiology and screening of asbestos-related diseases. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2000;26:449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doll R. Mortality from lung cancer in asbestos workers. Br J Ind Med. 1955;12:81–86. doi: 10.1136/oem.12.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selikoff IJ, Churg J, Hammond EC. Asbestos exposure and neoplasia. JAMA. 1964;188:22–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.1964.03060270028006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martischnig KM, Newell DJ, Barnsley WC, Cowan WK, Feinmann EL, Oliver E. Unsuspected exposure to asbestos and bronchogenic carcinoma. Br Med J. 1977;1:746–749. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6063.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blot WJ, Harrington JM, Toledo A, Hoover R, Heath CW, Jr, Fraumeni JF., Jr Lung cancer after employment in shipyards during World War II. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:620–624. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197809212991202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.IARC. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1987. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markowitz SB, Levin SM, Miller A, Morabia A. Asbestos, asbestosis, smoking, and lung cancer. New findings from the North American insulator cohort. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2013;188:90–96. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201302-0257OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bignon J, Housset B, Brochard P, Pairon JC. Asbestos-related occupational lung diseases. Role of the pneumology unit in screening and compensation. Rev Mal Respir. 1999;16(Suppl 2):S42–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christiani DC. Smoking and the molecular epidemiology of lung cancer. Clin Chest Med. 2000;21:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70009-5. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schabath MB, Spitz MR, Delclos GL, Gunn GB, Whitehead LW, Wu X. Association between asbestos exposure, cigarette smoking, myeloperoxidase (MPO) genotypes, and lung cancer risk. Am J Ind Med. 2002;42:29–37. doi: 10.1002/ajim.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider J, Bernges U. CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 polymorphisms as modifying factors in patients with pneumoconiosis and occupationally related tumours: A pilot study. mol Med Report. 2009;2:1023–1028. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stucker I, Boffetta P, Antilla S, Benhamou S, Hirvonen A, London S, et al. Lack of interaction between asbestos exposure and glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 genotypes in lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2001;10:1253–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang LI, Neuberg D, Christiani DC. Asbestos exposure, manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) genotype, and lung cancer risk. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:556–564. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000128155.86648.a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei S, Wang LE, McHugh MK, Han Y, Xiong M, Amos CI, et al. Genome-wide gene-environment interaction analysis for asbestos exposure in lung cancer susceptibility. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1531–1537. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller DP, Liu G, De Vivo I, Lynch TJ, Wain JC, Su L, et al. Combinations of the variant genotypes of GSTP1, GSTM1, and p53 are associated with an increased lung cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2819–2823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society) Am Rev Respir Dis. 1978;118:1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–834. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IP, Gu J, Eisen T, et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet. 2008;40:616–622. doi: 10.1038/ng.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omenn GS, Goodman G, Thornquist M, Grizzle J, Rosenstock L, Barnhart S, et al. The beta-carotene and retinol efficacy trial (CARET) for chemoprevention of lung cancer in high risk populations: Smokers and asbestos-exposed workers. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2038s–2043s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cullen MR, Barnett MJ, Balmes JR, Cartmel B, Redlich CA, Brodkin CA, et al. Predictors of lung cancer among asbestos-exposed men in the {beta}-carotene and retinol efficacy trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:260–270. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luce D, Stucker I, Group IS. Investigation of occupational and environmental causes of respiratory cancers (ICARE): A multicenter, population-based case-control study in France. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:928. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sprince NL, Oliver LC, McLoud TC, Eisen EA, Christiani DC, Ginns LC. Asbestos exposure and asbestos-related pleural and parenchymal disease. Associations with immune imbalance. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:822–828. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.4_Pt_1.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnhart S, Keogh J, Cullen MR, Brodkin C, Liu D, Goodman G, et al. The CARET asbestos-exposed cohort: baseline characteristics and comparison to other asbestos-exposed cohorts. Am J Ind Med. 1997;32:573–581. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199712)32:6<573::aid-ajim1>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guida F, Paget-Bailly S, Lamkarkach F, Gaye O, Ducamp S, Menvielle G, et al. Risk of lung cancer associated with occupational exposure to mineral wools: updating knowledge from a french population-based case-control study, the ICARE study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2013;55:786–795. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318289ee8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hutter CM, Mechanic LE, Chatterjee N, Kraft P, Gillanders EM. Tank NCIG-ET. Gene-environment interactions in cancer epidemiology: A National Cancer Institute Think Tank report. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:643–657. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UCSC Genonme Bioinformatics. [Date Accessed: 2015/03/19];Genome Browser Website. http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html.

- 35.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Z, Taylor JA. SNPinfo: integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into functional SNP selection for genetic association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W600–W605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dayem Ullah AZ, Lemoine NR, Chelala C. SNPnexus: a web server for functional annotation of novel and publicly known genetic variants (2012 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W65–W70. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chelala C, Khan A, Lemoine NR. SNPnexus: a web database for functional annotation of newly discovered and public domain single nucleotide polymorphisms. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:655–661. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, Cheng Y, Schaub MA, Kasowski M, et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22:1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D930–D934. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Rienzo A, Testa JR. Recent advances in the molecular analysis of human malignant mesothelioma. La Clinica Terapeutica. 2000;151:433–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nymark P, Wikman H, Ruosaari S, Hollmen J, Vanhala E, Karjalainen A, et al. Identification of specific gene copy number changes in asbestos-related lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5737–5743. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bjorkqvist AM, Tammilehto L, Nordling S, Nurminen M, Anttila S, Mattson K, et al. Comparison of DNA copy number changes in malignant mesothelioma, adenocarcinoma and large-cell anaplastic carcinoma of the lung. Brit J Cancer. 1998;77:260–269. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baskerville S, Bartel DP. Microarray profiling of microRNAs reveals frequent coexpression with neighboring miRNAs and host genes. RNA. 2005;11:241–247. doi: 10.1261/rna.7240905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang B, Zhou Y, Lin N, Lowdon RF, Hong C, Nagarajan RP, et al. Functional DNA methylation differences between tissues, cell types, and across individuals discovered using the M&M algorithm. Genome Res. 2013;23:1522–1540. doi: 10.1101/gr.156539.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pasquinelli AE, Reinhart BJ, Slack F, Martindale MQ, Kuroda MI, Maller B, et al. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory RNA. Nature. 2000;408:86–89. doi: 10.1038/35040556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson CD, Esquela-Kerscher A, Stefani G, Byrom M, Kelnar K, Ovcharenko D, et al. The let-7 microRNA represses cell proliferation pathways in human cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7713–7722. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takamizawa J, Konishi H, Yanagisawa K, Tomida S, Osada H, Endoh H, et al. Reduced expression of the let-7 microRNAs in human lung cancers in association with shortened postoperative survival. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3753–3756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yanaihara N, Caplen N, Bowman E, Seike M, Kumamoto K, Yi M, et al. Unique microRNA molecular profiles in lung cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Esquela-Kerscher A, Trang P, Wiggins JF, Patrawala L, Cheng A, Ford L, et al. The let-7 microRNA reduces tumor growth in mouse models of lung cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:759–764. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.6.5834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kumar MS, Erkeland SJ, Pester RE, Chen CY, Ebert MS, Sharp PA, et al. Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:3903–398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee YS, Dutta A. The tumor suppressor microRNA let-7 represses the HMGA2 oncogene. Gene Dev. 2007;21:1025–1030. doi: 10.1101/gad.1540407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mayr C, Hemann MT, Bartel DP. Disrupting the pairing between let-7 and Hmga2 enhances oncogenic transformation. Science. 2007;315:1576–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.1137999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park SM, Shell S, Radjabi AR, Schickel R, Feig C, Boyerinas B, et al. Let-7 prevents early cancer progression by suppressing expression of the embryonic gene HMGA2. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:2585–2590. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.21.4845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sampson VB, Rong NH, Han J, Yang Q, Aris V, Soteropoulos P, et al. MicroRNA let-7a down-regulates MYC and reverts MYC-induced growth in Burkitt lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9762–9770. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, Zhang X, Pan Q, Gong C, et al. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swaminathan S, Suzuki K, Seddiki N, Kaplan W, Cowley MJ, Hood CL, et al. Differential regulation of the Let-7 family of microRNAs in CD4+ T cells alters IL-10 expression. J Immunol. 2012;188:6238–6246. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Driscoll KE, Carter JM, Howard BW, Hassenbein D, Burdick M, Kunkel SL, et al. Interleukin-10 regulates quartz-induced pulmonary inflammation in rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L887–L894. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.5.L887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huaux F, Louahed J, Hudspith B, Meredith C, Delos M, Renauld JC, et al. Role of interleukin-10 in the lung response to silica in mice. Am J Resp Cell Mol. 1998;18:51–59. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.1.2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang SX, Jaurand MC, Kamp DW, Whysner J, Hei TK. Role of mutagenicity in asbestos fiber-induced carcinogenicity and other diseases. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2011;14:179–245. doi: 10.1080/10937404.2011.556051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dopp E, Schiffmann D. Analysis of chromosomal alterations induced by asbestos and ceramic fibers. Toxicol Lett. 1998;96–97:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lohani M, Dopp E, Becker HH, Seth K, Schiffmann D, Rahman Q. Smoking enhances asbestos-induced genotoxicity, relative involvement of chromosome 1: a study using multicolor FISH with tandem labeling. Toxicol Lett. 2002;136:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Patel JD. Lung cancer in women. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3212–3218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thomas L, Doyle LA, Edelman MJ. Lung cancer in women: Emerging differences in epidemiology, biology, and therapy. Chest. 2005;128:370–381. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Belani CP, Marts S, Schiller J, Socinski MA. Women and lung cancer: Epidemiology, tumor biology, and emerging trends in clinical research. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paggi MG, Vona R, Abbruzzese C, Malorni W. Gender-related disparities in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010;298:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sharma S, Eghbali M. Influence of sex differences on microRNA gene regulation in disease. Biol Sex Differ. 2014;5:3. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pinto R, Pilato B, Ottini L, Lambo R, Simone G, Paradiso A, et al. Different methylation and microRNA expression pattern in male and female familial breast cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:1264–1269. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neri M, Ugolini D, Dianzani I, Gemignani F, Landi S, Cesario A, et al. Genetic susceptibility to malignant pleural mesothelioma and other asbestos-associated diseases. Mutat Res. 2008;659:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.