Abstract

Biomolecular separation is crucial for downstream analysis. Separation technique mainly relies on centrifugal sedimentation. However, minuscule sample volume separation and extraction is difficult with conventional centrifuge. Furthermore, conventional centrifuge requires density gradient centrifugation which is laborious and time-consuming. To overcome this challenge, we present a novel size-selective bioparticles separation microfluidic chip on a swinging bucket minifuge. Size separation is achieved using passive pressure driven centrifugal fluid flows coupled with centrifugal force acting on the particles within the microfluidic chip. By adopting centrifugal microfluidics on a swinging bucket rotor, we achieved over 95% efficiency in separating mixed 20 μm and 2 μm colloidal dispersions from its liquid medium. Furthermore, by manipulating the hydrodynamic resistance, we performed size separation of mixed microbeads, achieving size efficiency of up to 90%. To further validate our device utility, we loaded spiked whole blood with MCF-7 cells into our microfluidic device and subjected it to centrifugal force for a mere duration of 10 s, thereby achieving a separation efficiency of over 75%. Overall, our centrifugal microfluidic device enables extremely rapid and label-free enrichment of different sized cells and particles with high efficiency.

I. INTRODUCTION

Bioparticles found in peripheral fluids include diseased cells and submicron particles, such as subcellular components, bacteria, or microvesicles.1–3 Our bodily fluids carry many of these substances that provide vital information on the patient's disease burden.4–7 Currently, many research efforts emphasize on effective extraction of these extraordinary bioparticles.8–12 Indeed, the analysis of diseased bioparticles has potential for disease diagnosis,13,14 monitoring,15 and prognosis.16–18 However, the extraction of these rare particles is not trivial because of their microscopic size, extreme rarity, and extensive heterogeneity. Despite so, researchers have achieved separation of these rare particles by their size anomaly.19–23 Conventionally, density gradient centrifugation is utilized for particle fractionation. Density gradient centrifugation may be divided into two categories—rate-zonal centrifugation (separation according to size and mass) or isopycnic centrifugation (separation according to density).24–26 In biological applications, rate-zonal centrifugation is often adopted to obtain cellular components for further analysis.27,28 Typically, different density gradient concentrations are stacked unto a conical tube, from the lowest to the highest concentration. A sample is then loaded on top of the density gradient and subjected to ultracentrifuge of up to 1 000 000 × g repeatedly. Additional steps are then required to retrieve the particles from the density gradient media. Therefore, this process is not only laborious and time consuming, it also utilizes expensive equipment. Moreover, selection of an appropriate density gradient media is also not trivial.

Centrifugal microfluidics has been the core research theme for diagnostic applications for several decades.29,30 The miniaturized rotational platform offers many intrinsic advantages in particle and liquid handling.31 In fact, many researchers capitalize on the high rotational frequency to provide particle sedimentation, fractionation, isolation, separation among others.22,32–36 Recent advances capitalize on microfluidic design to achieve passive valving and inertial focusing within the centrifugal platform.37,38 Carboxylated microbeads are also recently utilized for specific biomolecular capture and extraction in a centrifugal platform.39,40 However, high-resolution separation or extraction of particles in the centrifugal system is typically complicated,9 and often requires adding density gradient media41 or other active labeling methods.32

Increasingly, there is also a pressing need to develop diagnostic tools that utilize low sample volumes in a high throughput and cost effective manner.10,42,43 In particular, low volume processing is highly attractive for continual disease monitoring as it reduces the burden on the patient. In fact, miniaturization is highly dependent on the sample and reagent volume, and is an important criterion in point-of-care devices.44–46 The ability to obtain enriched samples is also highly desired to improve diagnostic sensitivity. Furthermore, low volumes negate the requirements for additional accessories for sample storage and preservation.45 However, extraction of bioparticles from low sample volumes is especially challenging due to device specific requirements.

In this study, we adopted a density gradient free centrifugation to extract bioparticles using only 20 μL input volume. In particular, by adopting a commercial bench top minifuge, our microfluidic device is subjected to centrifugal forces of approximately 1300 × g, a fraction of the conventional ultracentrifuge. The separation principle is primarily based on the centrifugal forces acting in the radial direction. We demonstrated that the characteristic time of radial centrifugal force acting on the swinging bucket on the horizontal position is sufficient to achieve a distinguishable separation between different micron sized particles. Simultaneously, by manipulating the hydrodynamic resistance, we were able to adjust the flow velocity within the microfluidic chip under the compressive pressure when the swinging bucket is tilted to a vertical position. Specifically, we demonstrated liquid extraction of over 95% efficiency by separating the mixed colloidal dispersions within a 5 s centrifugation. Next, we introduced mixed colloidal dispersions unto the lower inlet of the microfluidic chip and subjected it under the same centrifugal force for 5 s. In this, we demonstrated that our device is able to separate particles into different outlets with a separation efficiency of up to 90%. To further prove our device utility for biological applications, we introduced spiked MCF-7 cells in diluted whole blood. We replaced the existing swinging bucket with our custom-fabricated swinging bucket to allow a longer radial centrifugal force for more distinct separation. Our device achieved separation efficiency of 75%. Overall, we demonstrated that our device is capable of separating micron sized particles in minute volumes of liquid in an ultrafast, label free and efficient manner.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

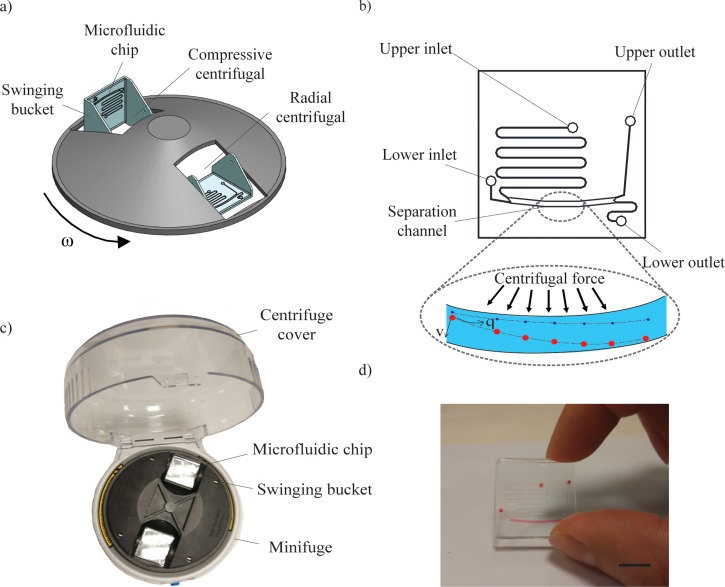

The schematic design of the centrifugal microfluidic separation system is illustrated in Fig. 1(a). Briefly, the mechanical rotor is set to spin the swinging bucket platform at a speed of 5000 rpm within the enclosure of 120 mm diameter. The microfluidic chip is secured within the swinging bucket and is subjected to both radial centrifugal and compressive centrifugal forces during the spin. The schematic of the microfluidic chip is further illustrated in Fig. 1(b). The microfluidic chip caters for two inlets and two outlets. The lower inlet is located with a hydrodynamic length of 10 mm away from the separation channel while the upper inlet is located with a hydrodynamic length of 100 mm away from the separation channel. The difference in hydrodynamic distance accounts for the difference in hydrodynamic resistance, which in turn, affects the advection velocity within the separation channel. Particles separation occurs in the separation channel of 1500 μm × 800 μm × 140 μm (L × W × H) and with curvature radius 50 mm. The microfluidic chip is sized 25 mm × 25 mm × 10 mm (L × W × H) which fits snugly into the swinging bucket. The microfluidic chip is fabricated using standard soft lithography techniques. Briefly, SU8 was patterned unto a silicon wafer to create topographical structures. Next, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Dow Corning Sylgard 184, Midland, MI) prepolymer mixed in 10:1 (w/w) ratio with curing agent was poured onto the silanized wafer and cured at 70 °C for 2 h. The cured silicone elastomer was removed from the mold and fluidic inlets and outlets were formed through hole-punching (1.2 mm). Finally, the PDMS microfluidic device was covalently bonded with a custom-cut glass slide (25 mm × 25 mm) using oxygen plasma treatment. The device is completed after curing in the oven at 70 °C for another 3 h. The actual centrifugal microfluidic system complete with two microfluidic chips on the swinging buckets is shown in Fig. 1(c). Furthermore, the fabricated microfluidic chip loaded with red dye is shown in Fig. 1(d).

FIG. 1.

Microfluidic chip within a swinging bucket minifuge. (a) Schematic illustration of the centrifugal microfluidic platform driven by radial and compressive centrifugal force. (b) Schematic of the microfluidic chip having two inlets, a separation channel, and two outlets. The separation channel drives particles of different sizes into different outlets. (c) Photograph of actual centrifugal microfluidic system mounted on a minifuge and (d) microfluidic device loaded with red color dye. Scale bar denotes 10 mm.

The microfluidic chip was primed with Milli-Q distilled water from the inlet with the outlets sealed. As proof of concept, polystyrene microbeads (Phosphorex, MA), each of density 1.05 kg/m3 but of different particle diameters, were mixed to form approximately 1% solid suspensions. The mixed colloidal dispersions was then loaded into the microfluidic chip on the upper inlet using a 1 ml plastic syringe (BD) attached to an 18 G blunt needle tip. The loading inlet and both outlets were left open to atmospheric air to prevent compressed air accumulation leading to reverse flow. The microfluidic chip was carefully placed on the swinging bucket and enclosed within the mechanical rotor centrifuge (Life Technologies, CA). The centrifuge was toggled for quick spin for 5 s before power is off. The microfluidic chip was then removed from the swinging bucket and observed under the microscope. Next, approximately 20 μl of suspension was slowly loaded into the lower inlet of a new microfluidic chip using a new 1 ml plastic syringe. Similarly, the loading inlet and both outlets were left open to atmospheric air. Again, the microfluidic chip was subjected to a quick centrifugal spin of 5 s. The microfluidic chip was removed from the centrifuge immediately and observed under the microscope. To further validate the separation efficiency, the loading inlet and respective outlets were observed under microscope. The images were captured and analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, US).

To demonstrate device utility, human breast adenocarcinoma cell line, MCF-7, pre-stained with lipophilic fluorescent dye dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide (Life Technologies, CA), was used for cell separation. The cells were cultured in low glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco®, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, CA) and 1% pencillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, CA). Cell culture was maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator (Sanyo, Japan). The media was replaced every 48 h until confluency. 0.05% trypsin and 0.53 mM EDTA solution were used to dissociate the cells from the bottom of the culture flask. The cells were transferred into a Falcon® tube for centrifugation to remove the media and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at approximately 104 cells/ml. Next, whole blood samples were obtained from healthy donors and diluted in PBS to ∼0.4% hematocrit. MCF-7 cells were then spiked into the diluted blood to obtain approximately 100 MCF-7 cells in each sample run. The spiked blood was loaded into the lower inlet of the microfluidic chip, similarly described above. The microfluidic chip was placed in a custom fabricated swinging bucket to allow a longer radial centrifugal force of 5 s for more effective separation. Following which, the microfluidic chip was transferred unto the normal swinging bucket for a quick 5 s centrifugal spin. The microfluidic chip was removed and observed under the microscope. Finally, the loading inlet and outlets were observed under brightfield and fluorescent microscopy. The images taken were further analyzed using ImageJ software.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The swinging bucket centrifugation comprises two phases—the radial centrifugation with the swinging bucket in the horizontal position and the compressive centrifugation with the swinging bucket in the vertical position. The separation principle occurs mainly in the radial centrifugation within a transient period of less than 2 s. During the transition, the microfluidic chip experiences both radial centrifugal force and compressive centrifugal force, providing simultaneous forces acting on the particles within the microfluidic chip to provide distinct separation. Subsequently, the centrifugal force is increased sufficiently to rotate the swinging bucket outwards such that the microfluidic chip experienced solely compressive centrifugal pressure. The compressive centrifugation pushes the sample towards the outlets for extraction. At the same time, the pressure across the ports is in equilibrium, ensuring that the fluid sample is maintained within the microfluidic chip. The centrifugal microfluidic device operates based on a compressive pressure driven fluid flow coupled with centrifugal flow mechanism. Briefly, the onset of centrifugation initiates positive force acting on the fluid inlet interface, thus generating a fluid flow towards the outlet. The advection fluid velocity can be mathematically expressed as

| (1) |

where ρf is the fluid density, ω is the angular velocity, and r2 and r1 are the distance from center of rotation of outlet and inlet, respectively. Rtot represents the total hydrodynamic resistance of the microfluidic channel. The hydrodynamic resistance of the microfluidic channel is divided into two parts. The inlet channel leading to separation channel and outlet channel exiting the separation channel is of high aspect ratio (height/width > 1), while the separation channel is of low aspect ratio (height/width < 1). Accordingly, the hydrodynamic resistance, Rh, of the rectangular channels is calculated as below.

For separation channel of low aspect ratio47

| (2) |

For other channels of high aspect ratio47

| (3) |

where μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, L is the channel length, w is the channel width, h is the channel height, respectively.

At the same time, a centrifugal force field acts perpendicular to the axis of fluid flow direction. In particular, the particles flowing along the separation channel experienced a centrifugal force balanced by buoyancy and hydrodynamic drag, achieving terminal velocity v as described by

| (4) |

where d is the diameter of the particle, r is the distance from center of rotation, ω is the angular velocity, μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, and ρp represents the density of the particle.

Therefore, based on our centrifugal device, a centrifugal speed of 5000 rpm creates a centrifugal force of approximately 1300 × g. By accounting for the hydrodynamic resistance, the time taken for each particle to travel along the separation channel may be manipulated. This further determines the vertical displacement of each particle according to its particle diameter. According to Equation (2), the vertical displacement of the particle is proportional to the square of its particle diameter. Other forces, such as Coriolis force and Dean's force are acting on the particles but has minimal effect in comparison with the centrifugal force and the fluid flow. As such, a distinguishable separation between particle sizes could be established and bifurcations may be designed to separate these particles into different outlets. The pressure difference between the inlets and outlets generated by the centrifugal force translates to a pressure driven flow rate of 34.2 mm/s, thus the microbeads remain in the separation channel only for a residence time of 0.44 s. Given the time scale and centrifugal force acting on the microbeads, the migration distance of microbeads of various particle diameters may be calculated. Table I shows the comparison of calculated migration distance and actual migration distance of microbeads of different sizes.

TABLE I.

Comparison of migration distances (in μm) of particles.

| Φpa | Upper Inlet | Lower Inlet |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 7468 | 750 |

| 15 | 4201 | 422 |

| 10 | 1867 | 187 |

| 5 | 466 | 46.9 |

| 2 | 74.7 | 7.5 |

Φp is the particle diameter, in μm.

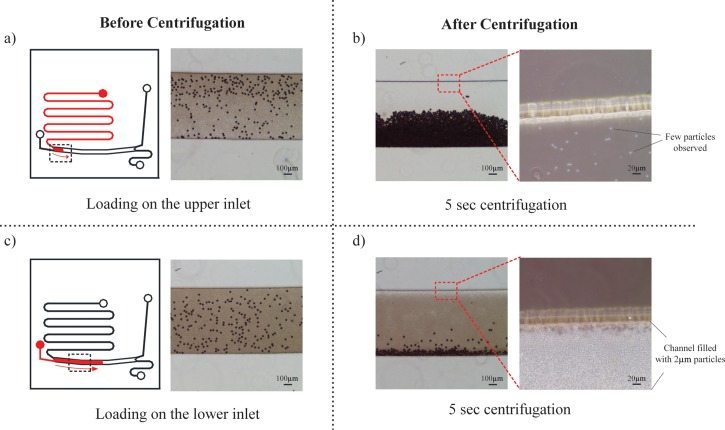

Size separation in the microfluidic chip is further described in Fig. 2. Fig. 2(a) depicts the particles in the separation channel before centrifugation. Within a short 5 s spin, the microbeads have all migrated laterally to the channel wall, as depicted in Fig. 2(b). The upper portion of the channel was further observed under 20× magnification microscope. Only a few 2 μm microbeads remained dispersed in the upper portion of the separation channel, possibly due to inertial forces and diffusive forces counteracting particles migration. Next, the mixed colloidal dispersion was loaded in the lower inlet. With a reduced hydrodynamic resistance, a significantly increased advection velocity of 340 mm/s was created. As such, the particles resided in the separation channel for only 40 ms. Interestingly, within this transition period, the 20 μm microbeads have migrated distinctly by a distance of 750 μm, while the 2 μm microbeads have migrated by only 7 μm, achieving selective separation. The microscopic images before and after centrifugation are shown in Figs. 2(c) and 2(d), respectively. Particularly, the 20× magnified image of the upper portion of the separation channel shows a thin bead-free layer, further indicating the marginal migratory distance of the 2 μm microbeads.

FIG. 2.

Microbeads separation in centrifugal microfluidic device. Mixed microbeads (20 μm and 2 μm) were loaded on the upper inlet. Brightfield images of the microparticles (a) before centrifugation and (b) after centrifugation within the separation channel. Only very few 2 μm microbeads were observed in the upper portion of the channel. Subsequently, mixed microbeads (20 μm and 2 μm) were loaded on the lower inlet. Brightfield images of the microparticles (c) before centrifugation and (d) after centrifugation within the separation channel. 2 μm microbeads remain dispersed in the upper portion of the channel. Dotted box represent corresponding microscopic image locations.

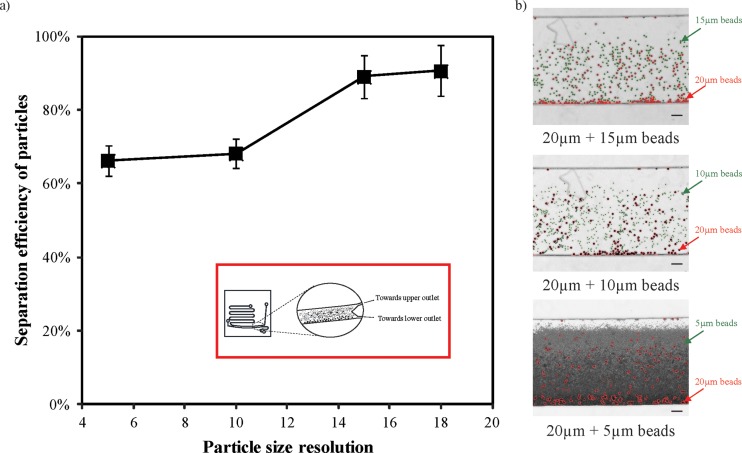

To further characterize the performance of the size separation, we loaded polydispersed microbeads of different diameters (i.e., 20 μm and 2 μm, 20 μm and 5 μm, 20 μm and 10 μm, 20 μm and 15 μm) into the lower inlet and subjected it to 5 s centrifugal spin. As centrifugal force acts to the square of the particle diameter, a distinct difference in the particle diameter leads to a more distinguishable separation. Fig. 3(a) shows the relationship of separation efficiency with reducing particle size resolution. With mixed microbeads of 5 μm size difference, we attained a size separation efficiency of approximately 65%. However, with increasing difference in the particle diameters, the separation efficiency increases significantly. At the size resolution of 18 μm, i.e., between 20 μm and 2 μm microbeads, we achieved size separation of over 90%. The representative optical images of the particles spanning across different sizes in the microfluidic chip are further depicted in Fig. 3(b). Here, we observed that the larger particles are enriched towards the lower half of the separation channel. The smaller particles have migrated less distinctly, evidently observed with decreasing particle diameters. Overall, our microfluidic chip has demonstrated its utility in separating particles of different sizes.

FIG. 3.

Size separation of polydispersed microbeads in the centrifugal microfluidic device. (a) Graph shows the relationship between the separation efficiency of mixed particles and its size resolution. Inset denotes the schematic diagram of the size separation within the microfluidic channel. (b) Representative images of the oligosuspended particles in the microfluidic channel after centrifugation, larger particles are outlined in red, smaller particles are outlined in green. Scale bar denotes 100 μm.

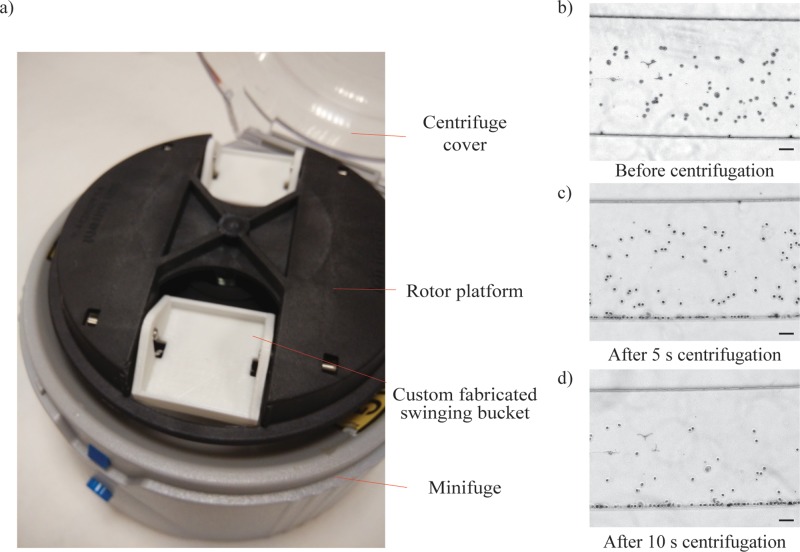

Cell suspension was initially subjected to the same centrifugal spin protocol as the microbeads suspension. Interestingly, even though MCF-7 cells were reported to be of similar size and density to the 20 μm microbeads,48 no significant migration was observed in the separation channel. The deformable cells experienced an additional lift force,11 resulting in inertia in movement within the separation channel. As such, a longer characteristic time within the separation channel is required to separate cells of different sizes. To overcome this, a custom designed swinging bucket was fabricated such that the microfluidic chip was subjected to a longer radial centrifugal force, as depicted in Fig. 4(a). The microfluidic chip was held in place horizontally within the custom fabricated swinging bucket during centrifugation, allowing longer radial centrifugation. Fig. 4(b) shows the MCF-7 cells dispersed uniformly across the microfluidic channel before centrifugation. After 5 s centrifugation, approximately 60% of the MCF-7 cells have migrated to the outer channel wall, as shown in Fig. 4(c). With an additional 5 s of radial centrifugation, approximately 80% of the MCF-7 cells have migrated distinctly to the outer channel wall.

FIG. 4.

Characterization of the custom fabricated swinging bucket in the centrifugal microfluidic device. (a) Photograph of the custom fabricated swinging bucket that locks the microfluidic chip in horizontal position within the minifuge. (b) Brightfield image of MCF-7 cells dispersed within the microfluidic channel before centrifugation. (c) Brightfield image of MCF-7 shows little migration after 5 s radial centrifugation. (c) Significant proportion of MCF-7 cells has migrated distinctly to the outer channel wall after 10 s centrifugation. Scale bar represents 100 μm.

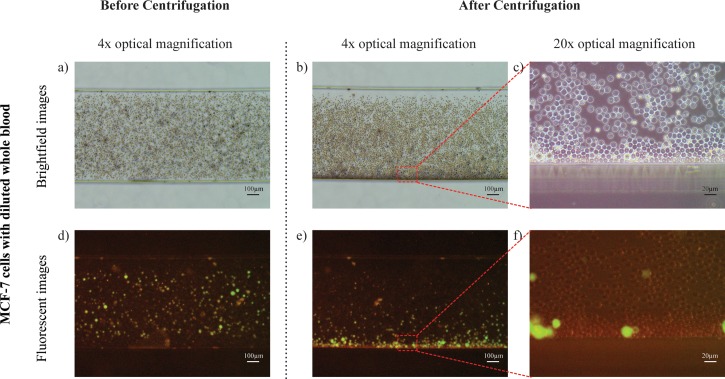

Next, we introduced spiked whole blood with MCF-7 cells into our microfluidic chip and observed the microfluidic chip under brightfield and fluorescence microscopy as depicted in Figs. 5(a) and 5(d), respectively. After centrifugation, the microfluidic chip was again observed under brightfield and fluorescence microscopy as depicted in Figs. 5(b) and 5(e), respectively. Magnified brightfield and fluorescence images were further observed at the bottom of the separation channel in Figs. 5(c) and 5(f), respectively. We observed that the MCF-7 cells have migrated to the bottom of the separation channel. The cells were also clearly shown from the fluorescent images, indicating that the brief centrifugation did not result in excessive cell lysis. The red blood cells remained dispersed across the entire channel, indicating that the applied centrifugal force was insufficient to provide significant force to drive the red bloods cells to the bottom of the channel. Overall, the results indicated the capability of sorting deformable bioparticles according to size.

FIG. 5.

Cells separation in the centrifugal microfluidic device. MCF-7 cells mixed with diluted whole blood were loaded into a new microfluidic chip. Representative images of MCF-7 cells with diluted whole blood under brightfield microscopy within the separation channel (a) before centrifugation and (b) after centrifugation. (c) Representative image under 20× optical magnification at the bottom of the separation channel indicating MCF-7 cells migration. (d)–(f) Corresponding images under fluorescence microscopy indicating the separation of the MCF-7 cells.

The centrifugal separation of different sizes of beads and cells was studied. The separation efficiency, Sp, defined as the proportion of particles collected over the lower outlet, is calculated as

| (5) |

where Co and Ci are particle count per microliter at the upper outlet and loading inlet, respectively. The migration efficiency, Mp, of the beads and cells were also compared. The migration efficiency is defined as

| (6) |

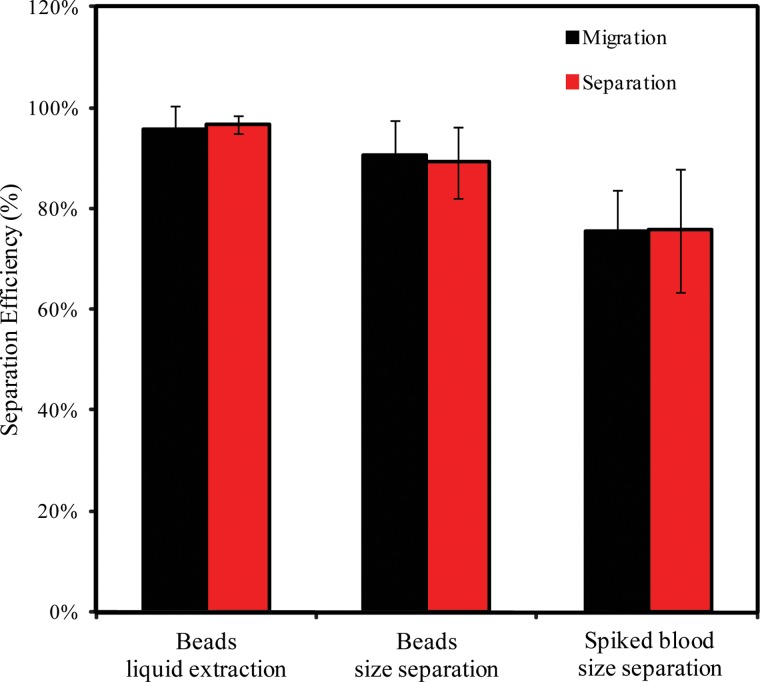

where Cs and Cm are particle count within the separation channel before and after centrifugation, respectively. Fig. 6 shows the relationship of the cells and particles separation efficiency. It is clear that the separation efficiency retrieved at the outlet is comparable to the migration efficiency at the separation channel, indicating few crossovers during the downstream collection. Our device has achieved over 95% efficiency in separating 2 μm and 20 μm mixed colloidal dispersions from its liquid carrier. Furthermore, the same microfluidic chip has achieved high separation efficiency of over 90% in separating 20 μm microbeads from 2 μm microbeads. Next, we achieved separation of spiked MCF-7 cells in diluted whole blood with increased radial centrifugation. Finally, we achieved separation of spiked MCF-7 cells in diluted whole blood with a separation efficiency of 75%. The loss in separation efficiency could be due to other factors such as heterogeneity in size, density and stiffness for each cell.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of separation and migration efficiency of cells and particles on the centrifugal microfluidic device.

Depending on the loading density, some particles may remain in the separation channel. Additional centrifugal spin may be required to drive the particles to the desired outlets. However, particles near the channel wall particularly experienced high inertial force which may limit the migration of these particles. Retrieval of these particles could be easily achieved by introducing liquid with a syringe pump via the upper inlet.

Typical size-separation microfluidic devices require sophisticated functional elements such as filter, conductive electrodes, or surface modification. Peripheral accessories such as pumps, tubings, and connectors are also necessary during the operation set up. These additional setups inevitably increases labor requirements and platform cost. In contrast, by using a standard swinging bucket rotor to process the samples, we decreased the instrumentation required. Moreover, we used a simple plastic syringe to load the samples within the microfluidic chip. Similarly, the enriched sample may be extracted from the outlet using a micropipette. Remarkably, the entire process takes less than 1 min, enabling a rapid and cost-effective separation technology.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

Centrifugal microfluidics offers an attractive label-free separation technique and has been demonstrated its utility on many lab-on-CD applications. Undeniably, centrifugal microfluidics is the closest platform in achieving sample to answer possibilities with many proven features such as pumping, valving, decanting, fluid splitting, etc.30 Using an existing low footprint swinging bucket rotor centrifuge, we developed a microfluidic chip that possesses the combination of fluid pressure driven flow and centrifugal force to provide a distinguishable separation between microparticles of different sizes. Remarkably, the size selection separation microfluidic chip is highly versatile as different microfluidic chip designs can be easily implemented in the system. With a single microfluidic chip, we demonstrated its capability of manipulating the device to performing liquid extraction with over 95% efficiency or size separation up to 90% efficiency. In this work, we further demonstrated the separation of MCF-7 cells spiked blood samples and attained a separation efficiency of 75%. In summary, we achieved efficient label-free size separation using minuscule sample volumes within 10 s. Furthermore, the simple fabrication process and integration with existing standard benchtop centrifuge and accessories increase its cost effectiveness. Importantly, the rapid and efficient extraction of bioparticles in different outlets can enable better downstream processing for researchers and clinicians.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Agency of Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR), Singapore Institute of Manufacturing Technology (SIMTech). This work was also supported by the use of the lab facilities at the Mechanobiology Institute (MBI) and the MechanoBioEngineering Laboratory at the National University of Singapore.

References

- 1. Pratt E. D., Huang C., Hawkins B. G., Gleghorn J. P., and Kirby B. J., Chem. Eng. Sci. 66(7), 1508–1522 (2011). 10.1016/j.ces.2010.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hou H. W., Bhagat A. A. S., Lee W. C., Huang S., Han J., and Lim C. T., Micromachines 2(4), 319–343 (2011). 10.3390/mi2030319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taylor D. D. and Gercel-Taylor C., Front. Genet. 4, 142 (2013). 10.3389/fgene.2013.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Speicher M. R. and Pantel K., Nat. Biotechnol. 32(5), 441–443 (2014). 10.1038/nbt.2897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. L. A. Diaz, Jr. and Bardelli A., J. Clin. Oncol.: Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 32(6), 579–586 (2014). 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alix-Panabieres C. and Pantel K., Clin. Chem. 59(1), 110–118 (2013). 10.1373/clinchem.2012.194258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heitzer E., Ulz P., and Geigl J. B., Clin. Chem. 61(1), 112–123 (2015). 10.1373/clinchem.2014.222679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirby D., Glynn M., Kijanka G., and Ducrée J., Cytometry Part A 87(1), 74–80 (2015). 10.1002/cyto.a.22588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yu Z. T., Aw Yong K. M., and Fu J., Small 10(9), 1687–1703 (2014). 10.1002/smll.201302907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kersaudy–Kerhoas M. and Sollier E., Lab Chip 13(17), 3323–3346 (2013). 10.1039/c3lc50432h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hur S. C., Henderson-MacLennan N. K., McCabe E. R., and Di Carlo D., Lab Chip 11(5), 912–920 (2011). 10.1039/c0lc00595a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bhagat A. A., Bow H., Hou H. W., Tan S. J., Han J., and Lim C. T., Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 48(10), 999–1014 (2010). 10.1007/s11517-010-0611-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang J., Zhang K. Y., Liu S. M., and Sen S., Molecules 19(2), 1912–1938 (2014). 10.3390/molecules19021912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kosaka N., Iguchi H., and Ochiya T., Cancer Sci. 101(10), 2087–2092 (2010). 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01650.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crowley E., Di Nicolantonio F., Loupakis F., and Bardelli A., Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 10(8), 472–484 (2013). 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bettegowda C., Sausen M., Leary R. J., Kinde I., Wang Y., Agrawal N., Bartlett B. R., Wang H., Luber B., Alani R. M., Antonarakis E. S., Azad N. S., Bardelli A., Brem H., Cameron J. L., Lee C. C., Fecher L. A., Gallia G. L., Gibbs P., Le D., Giuntoli R. L., Goggins M., Hogarty M. D., Holdhoff M., Hong S.-M., Jiao Y., Juhl H. H., Kim J. J., Siravegna G., Laheru D. A., Lauricella C., Lim M., Lipson E. J., Marie S. K. N., Netto G. J., Oliner K. S., Olivi A., Olsson L., Riggins G. J., Sartore-Bianchi A., Schmidt K., Shih L.-M., Oba-Shinjo S. M., Siena S., Theodorescu D., Tie J., Harkins T. T., Veronese S., Wang T.-L., Weingart J. D., Wolfgang C. L., Wood L. D., Xing D., Hruban R. H., Wu J., Allen P. J., Schmidt C. M., Choti M. A., Velculescu V. E., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B., Papadopoulos N., and Diaz L. A., Sci. Transl. Med. 6(224), 224 (2014) 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cristofanilli M., Budd G. T., Ellis M. J., Stopeck A., Matera J., Miller M. C., Reuben J. M., Doyle G. V., Allard W. J., Terstappen L. W. M. M., and Hayes D. F., N. Engl. J. Med. 351(8), 781–791 (2004). 10.1056/NEJMoa040766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lim S. H., Becker T. M., Chua W., Caixeiro N. J., Ng W. L., Kienzle N., Tognela A., Lumba S., Rasko J. E., de Souza P., and Spring K. J., Cancer Lett. 346(1), 24–33 (2014). 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hou H. W., Warkiani M. E., Khoo B. L., Li Z. R., Soo R. A., Tan D. S., Lim W. T., Han J., Bhagat A. A., and Lim C. T., Sci. Rep. 3, 1259 (2013). 10.1038/srep01259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun J., Liu C., Li M., Wang J., Xianyu Y., Hu G., and Jiang X., Biomicrofluidics 7(1), 11802 (2013). 10.1063/1.4774311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jin C., McFaul S. M., Duffy S. P., Deng X., Tavassoli P., Black P. C., and Ma H., Lab Chip 14(1), 32–44 (2014). 10.1039/C3LC50625H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee A., Park J., Lim M., Sunkara V., Kim S. Y., Kim G. H., Kim M. H., and Cho Y. K., Anal. Chem. 86(22), 11349–11356 (2014). 10.1021/ac5035049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu Z., Zhang W., Huang F., Feng H., Shu W., Xu X., and Chen Y., Biosens. Bioelectron. 47, 113–119 (2013). 10.1016/j.bios.2013.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mori Y., KONA Powder Part. J. 32, 102–114 (2015). 10.14356/kona.2015023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Majekodunmi S. O., Am. J. Biomed. Eng. 5(2), 67–78 (2015) 10.5923/j.ajbe.20150502.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Akbulut O., Mace C. R., Martinez R. V., Kumar A. A., Nie Z., Patton M. R., and Whitesides G. M., Nano Lett. 12(8), 4060–4064 (2012). 10.1021/nl301452x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tauro B. J., Greening D. W., Mathias R. A., Ji H., Mathivanan S., Scott A. M., and Simpson R. J., Methods 56(2), 293–304 (2012). 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dainiak M., Kumar A., Galaev I., and Mattiasson B., in Cell Separation, edited by Kumar A., Galaev I., and Mattiasson B. ( Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007), Vol. 106, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Burger R. and Ducrée J., Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 12(4), 407–421 (2012). 10.1586/erm.12.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gorkin R., Park J., Siegrist J., Amasia M., Lee B. S., Park J. M., Kim J., Kim H., Madou M., and Cho Y. K., Lab Chip 10(14), 1758–1773 (2010). 10.1039/b924109d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Burger R., Kirby D., Glynn M., Nwankire C., O'Sullivan M., Siegrist J., Kinahan D., Aguirre G., Kijanka G., Gorkin R. A. III, and Ducree J., Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 16(3–4), 409–414 (2012). 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ducrée J., Haeberle S., Lutz S., Pausch S., Stetten F. V., and Zengerle R., J. Micromech. Microeng. 17(7), S103–S115 (2007). 10.1088/0960-1317/17/7/S07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haeberle S., Brenner T., Zengerle R., and Ducree J., Lab Chip 6(6), 776–781 (2006). 10.1039/b604145k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kato H. and Nakamura A., Anal. Methods 6(10), 3215 (2014). 10.1039/c3ay42203h [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pertaya–Braun N., Baier T., and Hardt S., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 12(1–4), 317–324 (2012). 10.1007/s10404-011-0875-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kuo J.-N. and Chen X.-F., Microsyst. Technol. 21(11), 2485–2494 (2015) 10.1007/s00542-015-2408-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Al-Faqheri W., Ibrahim F., Thio T. H. G., Aeinehvand M. M., Arof H., and Madou M., Sens. Actuators, A 222, 245–254 (2015). 10.1016/j.sna.2014.12.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Al-Faqheri W., Ibrahim F., Thio T. H., Bahari N., Arof H., Rothan H. A., Yusof R., and Madou M., Sensors 15(3), 4658–4676 (2015). 10.3390/s150304658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aguirre G. R., Efremov V., Kitsara M., and Ducrée J., Microfluid. Nanofluid. 18(3), 513–526 (2015). 10.1007/s10404-014-1450-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Strohmeier O., Keil S., Kanat B., Patel P., Niedrig M., Weidmann M., Hufert F., Drexler J., Zengerle R., and von Stetten F., RSC Adv. 5(41), 32144–32150 (2015). 10.1039/C5RA03399C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Feshitan J. A., Chen C. C., Kwan J. J., and Borden M. A., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 329(2), 316–324 (2009). 10.1016/j.jcis.2008.09.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yager P., Edwards T., Fu E., Helton K., Nelson K., Tam M. R., and Weigl B. H., Nature 442(7101), 412–418 (2006). 10.1038/nature05064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lee W. G., Kim Y.-G., Chung B. G., Demirci U., and Khademhosseini A., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 62(4–5), 449–457 (2010). 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kiechle F. L. and Holland C. A., Clin. Lab. Med. 29(3), 555–560 (2009). 10.1016/j.cll.2009.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Weigl B., Domingo G., LaBarre P., and Gerlach J., Lab Chip 8(12), 1999–2014 (2008). 10.1039/b811314a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sia S. K. and Kricka L. J., Lab Chip 8(12), 1982–1983 (2008). 10.1039/b817915h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tanyeri M., Ranka M., Sittipolkul N., and Schroeder C. M., Lab Chip 11(10), 1786–1794 (2011). 10.1039/c0lc00709a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lara O., Tong X., Zborowski M., and Chalmers J. J., Exp. Hematol. 32(10), 891–904 (2004). 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]