Abstract

Background

Compared with normal-weight women, women with obesity experience poorer breastfeeding outcomes. Successful breastfeeding among women with obesity is important for achieving national breastfeeding goals.

Objectives

The objectives were to determine whether the negative association between obesity and any or exclusive breastfeeding at 1 and 2 mo postpartum is mediated through breastfeeding problems that occur in the first 2 wk postpartum and if this association differs by parity.

Methods

Mothers (1151 normal-weight and 580 obese) in the Infant Feeding Practices Study II provided information on sociodemographic and psychosocial characteristics, body mass index, and breastfeeding outcomes. At 1 mo postpartum, participants reported the breastfeeding problems they experienced in the first 2 wk postpartum from a predefined list of 17 options. We used factor analysis to condense these problems into 4 explanatory variables; continuous factor scores were computed for use in further analyses. We used maximum likelihood logistic regression to assess mediation of the association between obesity and breastfeeding outcomes through early breastfeeding problems.

Results

No significant effect of obesity was found on any breastfeeding at 1 or 2 mo. At 1 mo postpartum, for both primiparous and multiparous women, there was a significant direct effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding and a significant indirect effect of obesity through early breastfeeding problems related to the explanatory mediating variable “Insufficient Milk” (throughout the remainder of the Abstract, this factor will be denoted by upper case notation). At 2 mo postpartum both the direct effect of obesity and the indirect effect through Insufficient Milk were significant in primiparous women but only the indirect effect remained significant in multiparous women.

Conclusions

Early problems related to Insufficient Milk may partially explain the association between obesity and poor exclusive breastfeeding outcomes. Women who are obese, particularly those reporting breastfeeding problems that grouped in the Insufficient Milk factor in the early postpartum period, may benefit from additional breastfeeding support.

Keywords: maternal obesity, BMI, early breastfeeding problems, breastfeeding cessation, mediation analysis

Introduction

Women with obesity are less likely ever to breastfeed and are more likely to cease breastfeeding earlier than their normal-weight counterparts (1–3), despite similar intentions to breastfeed (4). Breastfeeding is the recommended mode of infant feeding (5) and improving national breastfeeding outcomes is an important public health goal (6, 7). Given that nearly one-fifth of women giving birth in the United States are obese (8), the breastfeeding success of these women is important for achieving this national goal.

In previous analyses of the Infant Feeding Practices Study II (IFPS II)6, Hauff et al. (4) showed that obesity was negatively associated with the duration of exclusive breastfeeding after controlling for breastfeeding intention, knowledge, and support. These findings suggest that obesity influences breastfeeding in ways unrelated to these psychosocial variables. In addition, the negative association between obesity and breastfeeding duration is consistent across societies with and without strong support for breastfeeding (9, 10), suggesting that there may be a biological explanation.

Possible biological explanations for poorer breastfeeding outcomes in women with obesity are that they are more likely than normal-weight women to experience a delayed prolactin response to suckling (11) and delayed onset of lactogenesis II (12, 13), which is predictive of the early cessation of any and exclusive breastfeeding (14). Women with obesity also exhibit general suboptimal breastfeeding behavior (15, 16), as measured by observation of a single breastfeeding episode that is based on evaluation with the use of the International Breastfeeding Assessment Tool (17). It was suggested that suboptimal breastfeeding behavior in women with obesity may be related to difficulties with positioning because of increased breast size; however, Nommsen-Rivers et al. (15) found that the positive relation between suboptimal breastfeeding behavior and obesity was not modified by bra cup size.

More recently, Stuebe et al. (18) found that, among mothers in the IFPS II who initiated breastfeeding, women with obesity were more likely to experience disrupted lactation, defined as reporting ≥2 of the following problems: breast pain, low milk supply, and difficulty with infant latch, than normal-weight women. They also found that disrupted lactation was associated with early weaning.

Primiparity is associated with delayed lactogenesis II (15, 16, 19) and suboptimal breastfeeding behavior (16). Wagner et al. (20) found that breastfeeding concerns were prevalent among primiparous women in the early postpartum period and that these concerns were associated with breastfeeding cessation. “Infant feeding difficulty” and “milk quantity” concerns resulted in the largest adjusted population attributable risk of stopping breastfeeding by 2 mo postpartum (20). As noted by Wagner et al. (20), early breastfeeding problems are especially important because they occur during a time when there may be a gap between hospital and community lactation support.

Not only is parity associated with suboptimal breastfeeding behavior and delayed lactogenesis II, the association between BMI and breast feeding duration were previously shown to depend on parity (21), with obese primiparous women most at risk of cessation of exclusive breastfeeding. Consequently, we stratified our analyses by parity to assess this interaction in this cohort because identifying women most at risk of early breastfeeding cessation and providing them with additional support may be a successful strategy to improve breastfeeding outcomes.

We hypothesized that 1) obesity is positively associated with early breastfeeding problems, 2) early breastfeeding problems are associated with poorer breastfeeding outcomes, and 3) the association between obesity and poor breastfeeding outcomes is mediated through early breastfeeding problems. We expected that this mediation pathway would be modified by parity, with primiparous women more affected than multiparous women.

Methods

Sample

The sample for this analysis consisted of participants of the IFPS II, a longitudinal cohort study of mothers of infants studied from late pregnancy through 1 y postpartum. Subjects for this cohort were drawn from a nationally distributed consumer opinion panel in the United States. Sociodemographic and infant feeding data were collected via mail-in questionnaires, 1 questionnaire prenatally and 10 postpartum. Data were collected between May 2005 and June 2007. Detailed information on the methods of the IFPS II can be found elsewhere (22).

Women (n = 3033) who completed both the birth screener and the neonatal questionnaire were available for this analysis. Of these women, 39 were ineligible because they lacked data on prepregnancy weight or height, variables necessary to calculate BMI (in kg/m2), and 77 were ineligible because they lacked data on parity, an important variable for our subgroup analyses. To reduce the potential bias caused by under-reporting of weight, which is well documented in the literature (23, 24), we chose to exclude underweight women ([BMI: <18.5; n = 136) and overweight women (BMI: 25–29.9; n = 753) and to compare normal-weight women with women with obesity. Under-reporting of weight increases as BMI increases (23), so, although it is possible that the normal-weight group contains some overweight women, it is unlikely that the obese group contains normal-weight or overweight women. As such, the 2 BMI categories compared for this study are likely to be distinct. Of the 2028 women remaining, 297 never initiated breastfeeding; therefore, we included 1731 women in our final analyses: 1151 normal-weight women (BMI: 18.5–24.9) and 580 women with obesity (BMI: ≥30). This research was considered exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Cornell University.

Variables used in analyses

Independent variable

Prepregnancy BMI was coded as normal-weight (18.5–24.9) or obese (≥30) on the basis of self-reported height and preconception weight provided on the prenatal questionnaire.

Dependent variables

This analysis focuses on breastfeeding to 2 mo postpartum because early breastfeeding outcomes are most likely to be associated with breastfeeding problems in the first 2 wk postpartum, the mediator of interest. The outcomes analyzed in this study were any and exclusive breastfeeding at the neonatal questionnaire (yes/no at ~1 mo postpartum) and any and exclusive breastfeeding at the second postpartum questionnaire (yes/no at ~2 mo postpartum). The outcome variables for any and exclusive breastfeeding were created on the basis of the infant’s 7-d food-frequency recall at the time the questionnaire was completed. If an infant consumed any breast milk in the previous 7 d, it was coded as any breastfeeding. If an infant consumed only breast milk with no formula, food, or water in the previous 7 d, it was coded as exclusively breastfeeding.

Potential mediating variables to be examined

On the neonatal questionnaire (~1 mo postpartum),women were asked” Did you have any of the following problems breastfeeding your baby during your first 2 wk of breastfeeding?” Subjects were instructed to mark all problems that applied from a list of 17 potential options. We used factor analysis to group these dichotomous variables into more basic underlying variables (see Statistical analysis), which produced 4 continuous mediators for further analyses.

Covariates

Maternal age was included as a continuous variable. Maternal race/ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic other, and Hispanic (any race). Household income was categorized as percentage of the poverty income ratio (PIR): <185% PIR, between 185% and 350% PIR, and >350% PIR. Maternal education was categorized as high school education or less, some college education, or college graduate. Marital status was categorized as married or not married. Smoking status was a dichotomous yes/no variable that was based on the subject’s smoking status at the time the prenatal questionnaire was completed. Mode of delivery was categorized as vaginal, not induced or induced, or cesarean, unplanned or planned. Intended breastfeeding duration was categorized as ≤6 mo, 6–12 mo, and >12 mo. For multiparous women, past breastfeeding experience was categorized as yes if a woman had breastfed a previous infant for ≥1 mo or no if she had never breastfed or had breastfed a previous infant for <1 mo.

Psychosocial variables that were included in this analysis were social knowledge of breastfeeding (categorical, number of friends and relatives who breastfed), social influence toward breastfeeding (categorical score that included opinions of infant’s father, maternal and paternal grandmothers, obstetrician, and pediatrician toward breastfeeding), attitudes and behavioral beliefs toward breastfeeding (included mother’s opinion on the importance of breastfeeding), and maternal confidence in breastfeeding (how confident the mother was that she would breastfeed as long as her prenatal breastfeeding goal). The creation of these variables was described in detail elsewhere (4).

Statistical analysis

We compared sociodemographic characteristics and psychosocial factors between obese and normal-weight women within parity groups. We used chi-square tests for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables.

We used factor analysis to create continuous variables of early breastfeeding problems to be examined as potential mediators of the association between obesity and breastfeeding outcomes. We performed factor analysis with varimax rotation of the matrix of tetrachoric correlations of the 17 dichotomous early breastfeeding problems as one would conduct a factor analysis of the matrix of Pearson correlations for interval-scale variables. Factor analysis reduced the number of independent variables for use in later multivariate analyses and was an advantageous technique when the independent variables were likely to be highly correlated, as was the case here. An eigenvalue ≥1 was used as a cutoff for factor retention, resulting in the creation of 6 factors. However, 1 factor contained only 1 variable and another contained only 2 variables. Because singlet and doublet variable factors are not considered reliable, the factor analysis code was manually altered to reduce the number of factors retained until each factor contained at least 3 variables. This resulted in 4 continuous variables (factor I to factor IV), that included all 17 early breastfeeding problems, to be used in the mediation analyses. The overall grouping of the larger factors changed only minimally when forced to produce 4 factors. Each participant was then assigned a continuous factor score for each of these factors.

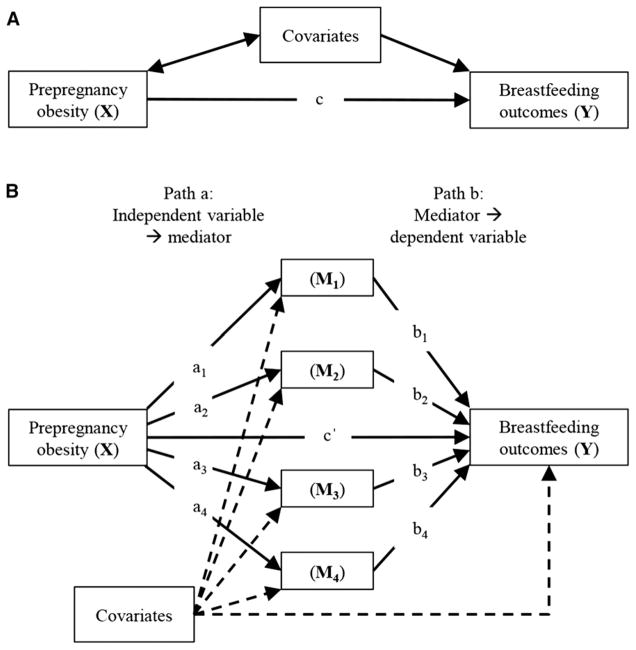

To test for mediation of the association between obesity and breastfeeding by early breastfeeding problems, we used the PROCESS macro for SAS (SAS Institute) (25), model 4, which uses listwise deletion and does not include cases with missing data in modeling effects. In these parallel, multiple-mediator models (Figure 1), factors I–IV were included as mediators of the association between obesity and dichotomous breastfeeding outcomes. The parallel, multiple-mediator model allowed us to assess the effects of >1 mediator adjusted for other mediators.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual diagrams of the simple (A) and complex (B) theoretical model used for analyses. ai estimates the effect of obesity on reporting specific early breastfeeding problems. bi estimates the effect of specific early breastfeeding problems on breastfeeding outcomes. aibi, the indirect effect, estimates differences in breastfeeding outcomes as a result of the effect of obesity on specific early breastfeeding problems. c quantifies how much women with obesity differ from normal-weight women on breastfeeding outcomes. c′ estimates the direct effect of obesity on breastfeeding outcomes, independent of the effect of obesity on early breastfeeding problems. ai, effect of independent variable on mediator; bi, effect of mediator on dependent variable; c′, direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable; M, mediator.

Total effects (X on Y), direct effects [X on Y, adjusted for mediating effects (M1–M4)], and specific indirect effects (X on Y through a specific mediator) were estimated with the use of a logistic regression-based, path-analytic framework (Figure 1B). The PROCESS macro calculates specific indirect effects of each potential mediator as the product of the ordinary least squares coefficient for the relation between the independent variable and the mediator (ai) and the logistic regression coefficient for the relation between the mediator and the dependent variable (bi). Mediation analyses included a bias-corrected bootstrap 95% CI (10,000 resamples) for the size of the total, direct, and indirect effects. Specific indirect effects were significant when CIs did not contain zero. It is important to note that the term effect is commonly used in mediation analyses; it means statistical effect, not causal effect.

All mediation models were conducted separately for primiparous and multiparous women. We adjusted for maternal characteristics and psychosocial variables known to be associated with breastfeeding, described earlier, by including them as covariates in models. Models were reduced with the use of backward step wise regression with covariates removed if they were not significant in the adjusted model (retention cutoff P ≤ 0.2). Analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Sample description

Among primiparous women, maternal obesity was significantly associated with maternal age, maternal education, mode of delivery, and social knowledge of breastfeeding (Table 1). No association was found between obesity and maternal race/ethnicity, household income, marital status, and prenatal smoking status. Interestingly, primiparous women with obesity did not differ from their normal-weight counterparts in intended breastfeeding duration, social influence toward breastfeeding, attitudes and behavioral beliefs toward breastfeeding, or confidence in breastfeeding.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and psychosocial characteristics of Infant Feeding Practices Study II participants by parity and obesity status1

| Primiparous (n = 550)

|

Multiparous (n = 1181)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | Normal-weight (n = 389) | Obese (n = 161) | P2 | Normal-weight (n = 762) | Obese (n = 419) | P2 |

| Maternal age, y | 0.0037 | 0.71 | ||||

| 18–24 | 154 (39.7) | 44 (27.3) | 104 (13.7) | 55 (13.1) | ||

| 25–29 | 130 (33.5) | 59 (36.7) | 280 (36.8) | 143 (34.1) | ||

| 30–34 | 73 (18.8) | 31 (19.2) | 243 (32) | 139 (33.2) | ||

| ≥35 | 31 (8) | 27 (16.8) | 133 (17.5) | 82 (19.6) | ||

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 21.9 (20.6 − 23.3) | 34.6 (31.6 − 37.9) | <0.0001 | 22.1 (20.8 − 23.5) | 34.5 (31.6 − 38.5) | <0.0001 |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | 0.07 | 0.62 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 298 (79.1) | 136 (86.6) | 622 (83.5) | 351 (85.6) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 23 (6.1) | 10 (6.4) | 30 (4) | 15 (3.7) | ||

| Non-Hispanic other | 30 (7.9) | 4 (2.5) | 44 (5.9) | 17 (4.1) | ||

| Hispanic (any race) | 26 (6.9) | 7 (4.5) | 49 (6.6) | 27 (6.6) | ||

| Household income, PIR | 0.91 | 0.002 | ||||

| <185% | 113 (29) | 49 (30.4) | 310 (40.7) | 209 (49.9) | ||

| 185–350% | 108 (27.8) | 42 (26.1) | 317 (41.6) | 161 (38.4) | ||

| >350% | 168 (43.2) | 70 (43.5) | 135 (17.7) | 49 (11.7) | ||

| Maternal education | 0.04 | 0.0006 | ||||

| ≤High school | 66 (18.8) | 32 (21.8) | 113 (15.6) | 89 (22.2) | ||

| Some college | 111 (31.5) | 60 (40.8) | 291 (40.1) | 178 (44.4) | ||

| College graduate | 175 (49.7) | 55 (37.4) | 321 (44.3) | 134 (33.4) | ||

| Marital status | 0.75 | 0.78 | ||||

| Not married | 114 (32.1) | 50 (33.6) | 98 (13.5) | 57 (14.1) | ||

| Married | 241 (67.9) | 99 (66.4) | 627 (86.5) | 347 (85.9) | ||

| Prenatal smoking | 0.28 | 0.51 | ||||

| Yes | 26 (6.7) | 15 (9.3) | 52 (6.8) | 33 (7.9) | ||

| No | 363 (93.3) | 146 (90.7) | 708 (93.2) | 386 (92.1) | ||

| Mode of delivery | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Vaginal, not induced | 174 (45) | 33 (20.7) | 354 (46.5) | 126 (30.1) | ||

| Vaginal, induced | 124 (32) | 56 (35.2) | 268 (35.2) | 126 (30.1) | ||

| Cesarean, unplanned | 68 (17.6) | 54 (34) | 27 (3.6) | 40 (9.5) | ||

| Cesarean, planned | 21 (5.4) | 16 (10.1) | 112 (14.7) | 127 (30.3) | ||

| Intended BF duration | 0.23 | 0.99 | ||||

| <6 mo | 119 (33.5) | 44 (31.4) | 211 (30.5) | 111 (30.4) | ||

| 6–12 mo | 208 (58.6) | 78 (55.7) | 361 (52.2) | 190 (52.1) | ||

| >12 mo | 28 (7.9) | 18 (12.9) | 120 (17.3) | 64 (17.5) | ||

| BF experience | <0.0001 | |||||

| No | — | — | 79 (10.5) | 79 (19.1) | ||

| Yes | — | — | 676 (89.5) | 335 (80.9) | ||

| Social knowledge of BF | 0.04 | <0.0001 | ||||

| 0 people/don3t know | 44 (11.3) | 29 (18.2) | 59 (7.8) | 67 (16.2) | ||

| 1–2 people | 76 (19.6) | 37 (23.3) | 128 (16.9) | 81 (19.6) | ||

| 3–5 people | 106 (27.3) | 44 (27.7) | 207 (27.4) | 119 (28.7) | ||

| >5 people | 162 (41.8) | 49 (30.8) | 362 (47.9) | 147 (35.5) | ||

| Social influence toward BF | 0.34 | 0.02 | ||||

| Low | 72 (18.5) | 31 (19.3) | 146 (19.2) | 106 (25.3) | ||

| Medium | 154 (39.6) | 73 (45.3) | 276 (36.2) | 154 (36.8) | ||

| High | 163 (41.9) | 57 (35.4) | 340 (44.6) | 159 (37.9) | ||

| Attitudes and behavioral beliefs | 0.39 | 0.21 | ||||

| Poor | 9 (2.3) | 4 (2.5) | 33 (4.3) | 27 (6.5) | ||

| Fair | 80 (20.6) | 25 (15.5) | 136 (17.9) | 81 (19.3) | ||

| Good | 300 (77.1) | 132 (82) | 593 (77.8) | 311 (74.2) | ||

| Maternal confidence in BF | 0.45 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Not confident | 16 (4.6) | 10 (7.2) | 36 (5.3) | 36 (10) | ||

| Neutral | 117 (33.2) | 47 (34.1) | 90 (13.1) | 90 (24.9) | ||

| Confident | 219 (62.2) | 81 (58.7) | 559 (81.6) | 235 (65.1) | ||

Values are n (%), unless otherwise indicated, BF, breastfeeding; PIR, poverty income ratio.

Determined by the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables.

Among multiparous women, maternal obesity was significantly associated with household income, maternal education, mode of delivery, breastfeeding experience, and social knowledge of breastfeeding (Table 1). No association was found between obesity and maternal age, race/ethnicity, marital status, prenatal smoking status, and attitudes and behavioral beliefs toward breastfeeding. Obese multiparous women had lower social influence toward breastfeeding and lower confidence in their ability to breastfeed until their planned duration than normal-weight multiparous women. However, obese multiparous women did not differ from normal-weight multiparous women in their intended breastfeeding duration.

Factor analysis of early breastfeeding problems

The most commonly reported problems with breastfeeding in the first 2 wk postpartum were “trouble getting milk flow to start,” and “baby had trouble sucking or latching” (Table 2). Factor analysis of the aforementioned 17 early breastfeeding problems resulted in the creation of 4 continuous variables composed of the problems that were most highly correlated (Table 3). Names were chosen for these factors on the basis of the main theme of the problems within each factor; consideration was also given to previous research into early breastfeeding concerns (20) and 2 factors (III and IV) were given names used by previous researchers because they were composed of similar problems. Factor I consisted of problems broadly related to “Insufficient Milk,” factor II consisted of problems related to “Breast Dysfunction,” factor III consisted of problems broadly related to “Too Much Milk,” and factor IV consisted of problems related to “Infant Feeding Difficulty” (Table 3). Throughout the remainder of the article, these factors will be denoted by upper case notation. Note that the problem “baby nursed too often” was highly negatively correlated with the other problems in factor IV. All other correlations in all factors were positive. Also note that not every problem seemed to match the name chosen for the factor it loaded with, for example “baby wouldn’t wake up to nurse” seems better related to the Infant Feeding Difficulty factor, not where it loaded statistically, Too Much Milk. However, the factor names were chosen on the basis of the main theme of the problems that grouped together.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of early breastfeeding problems by parity and obesity status among Infant Feeding Practices Study II participants1

| Primiparous (n = 550)

|

Multiparous (n = 1181)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem | Normal-weight (n = 389) | Obese (n = 161) | Normal-weight (n = 762) | Obese (n = 419) |

| Baby had trouble sucking or latching | 176 (45.6) | 97 (61) | 220 (29) | 139 (33.5) |

| Baby had trouble with choking | 42 (10.9) | 19 (11.9) | 101 (13.3) | 37 (8.9) |

| Baby wouldn’t wake up to nurse | 101 (26.2) | 44 (27.7) | 158 (20.8) | 90 (21.7) |

| Baby was not interested in nursing | 38 (9.8) | 22 (13.8) | 31 (4.1) | 31 (7.5) |

| Baby got distracted | 14 (3.6) | 14 (8.8) | 25 (3.3) | 19 (4.6) |

| Baby nursed too often | 49 (12.7) | 31 (19.5) | 114 (15) | 62 (14.9) |

| Baby did not gain/lost too much weight | 54 (14) | 33 (20.8) | 46 (6.1) | 46 (11.1) |

| Nipples were sore, cracked, or bleeding | 44 (11.4) | 23 (14.5) | 29 (3.8) | 32 (7.7) |

| Mom didn’t have enough milk for the baby | 69 (17.9) | 27 (17) | 68 (8.9) | 80 (19.3) |

| Took too long for milk to come in | 72 (18.7) | 46 (28.9) | 63 (8.3) | 75 (18.1) |

| Trouble getting milk flow to start | 196 (50.8) | 69 (43.4) | 388 (51.1) | 201 (48.4) |

| Breasts were overfull | 128 (33.2) | 54 (34) | 330 (43.4) | 122 (29.4) |

| Mom had yeast infection of the breast | 4 (1) | 5 (3.1) | 18 (2.4) | 8 (1.9) |

| Mom had clogged milk duct | 27 (7) | 10 (6.3) | 67 (8.8) | 30 (7.2) |

| Breasts were infected or abscessed | 4 (1) | 2 (1.3) | 20 (2.6) | 12 (2.9) |

| Breasts leaked too much | 52 (13.5) | 29 (18.2) | 108 (14.2) | 51 (12.3) |

| Mom had some other problem | 25 (6.5) | 16 (10) | 38 (5) | 28 (6.7) |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

Values are n (%) or n.

TABLE 3.

Factor analysis of breastfeeding problems experienced in the first 2 wk postpartum reported by Infant Feeding Practices Study II participants at 1 mo postpartum

| Factor number | Problem | Factor name |

|---|---|---|

| I | Took too long for milk to come in | Insufficient Milk |

| Baby did not gain/lost too much weight | ||

| Nipples were sore, cracked, or bleeding | ||

| Mom didn’t have enough milk for the baby | ||

| Baby had trouble sucking or latching | ||

| Baby got distracted | ||

| II | Breasts were infected or abscessed | Breast Dysfunction |

| Mom had clogged milk duct | ||

| Mom had yeast infection of the breast | ||

| Trouble getting milk flow to start | ||

| III | Breasts leaked too much | Too Much Milk |

| Baby had trouble with choking | ||

| Breasts were overfull | ||

| Baby wouldn’t wake up to nurse | ||

| IV | Baby was not interested in nursing | Infant Feeding Difficulty |

| Mom had some other problem | ||

| Baby nursed too often |

Breastfeeding prevalence by parity and obesity status

At 1 mo postpartum, 82% of normal-weight and 76% of obese primiparous women were breastfeeding, with 43% and 29% exclusively breastfeeding, respectively (Table 4). The prevalence of any breastfeeding at 2 mo decreased to 57% in normal-weight and 50% in obese primiparous women, with 36% and 23% exclusively breastfeeding, respectively. Normal-weight primiparous women were significantly more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at both 1 and 2 mo postpartum than their obese counterparts. Breastfeeding prevalence trends were similar among multiparous women, although the absolute figures were higher (Table 4). Normal-weight multiparous women were significantly more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at 1 and 2 mo postpartum, and they were also significantly more likely to be breastfeeding to any extent at 2 mo postpartum.

TABLE 4.

Prevalence of BF outcomes at 1 and 2 mo postpartum by parity and obesity status among Infant Feeding Practices Study II participants who initiated breastfeeding1

| Primiparous (n = 550)

|

Multiparous (n = 1181)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Normal-weight (n = 389) | Obese (n = 161) | Missing | P2 | Normal-weight (n = 762) | Obese (n = 419) | Missing | P2 |

| Any BF at 1 mo | 317 (81.5) | 122 (75.7) | 5 | 0.15 | 671 (88) | 359 (85.7) | 12 | 0.11 |

| Exclusive BF at 1 mo | 169 (43.4) | 46 (28.6) | 5 | 0.0013 | 422 (55.4) | 165 (39.4) | 12 | <0.0001 |

| Any BF at 2 mo | 222 (57.1) | 81 (50.3) | 86 | 0.07 | 542 (71.1) | 265 (63.2) | 170 | 0.0026 |

| Exclusive BF at 2 mo | 138 (35.5) | 37 (23) | 86 | 0.0021 | 349 (45.8) | 147 (35.1) | 170 | 0.0003 |

Values are n (% of total number in group). BF, breastfeeding.

Determined by the chi-square test.

Association between obesity and breastfeeding and mediation through early breastfeeding problems

In models adjusted for the covariates described previously, no significant total effect was found of obesity on any breastfeeding at 1 or 2 mo among primiparous or multiparous women. There was, however, a significant total effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding at both times among both primiparous and multiparous women.

We partially confirmed our first hypothesis that obesity is positively associated with early breastfeeding problems. Obesity was significantly positively associated with problems related to Insufficient Milk in all mediation models (a1 = 0.24 to 0.30; Table 5). However, contrary to our hypothesis, obesity was negatively associated with problems related to Breast Dysfunction (a2) and Too Much Milk (a3) among multiparous women at both 1 and 2 mo.

TABLE 5.

Path coefficients in adjusted mediation models of the association between obesity and exclusive BF among participants in the Infant Feeding Practices Study II1

| Primiparous (n = 550)

|

Multiparous (n = 1181)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | 1-mo Point estimate2 | P | 2-mo Point estimate | P | 1-mo Point estimate | P | 2-mo Point estimate | P |

| Obesity to mediator | ||||||||

| a1, Insufficient Milk | 0.30 | 0.004 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.24 | <0.0001 | 0.27 | <0.0001 |

| a2, Breast Dysfunction | −0.04 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 0.76 | −0.09 | 0.03 | −0.11 | 0.01 |

| a3, Too Much Milk | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.15 | −0.13 | 0.012 | −0.14 | 0.01 |

| a4, Infant Feeding Difficulty | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.005 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Mediator to exclusive BF | ||||||||

| b1, Insufficient Milk | −1.22 | <0.0001 | −0.83 | <0.0001 | −1.26 | <0.0001 | −1.18 | <0.0001 |

| b2, Breast Dysfunction | −0.53 | 0.05 | −0.30 | 0.28 | −0.22 | 0.18 | −0.15 | 0.38 |

| b3, Too Much Milk | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.55 |

| b4, Infant Feeding Difficulty | 0.04 | 0.87 | −0.23 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

Models were adjusted for maternal age, household income, maternal marital status, maternal race/ethnicity, delivery mode, prenatal smoking status, previous BF experience, intended duration of BF, social knowledge of BF, social influence toward BF, maternal confidence in BF, and behavioral beliefs about BF. Models were reduced with the use of backward stepwise regression with covariates removed if they were not significant in the adjusted model. Paths labeled a are paths from the independent variable to the mediating variable (factors I–IV). Paths labeled b are paths from the mediating variable to the dependent variable, exclusive BF. ai, effect of independent variable on mediator; bi, effect of mediator on dependent variable; BF, breastfeeding.

Point estimates are unstandardized B coefficients.

We also partially confirmed our second hypothesis that early breastfeeding problems are associated with poorer breastfeeding outcomes. Early problems that related to Insufficient Milk were negatively associated with exclusive breastfeeding outcomes in all mediation models (b1 = −0.83 to −1.26). However, among primiparous women, problems related to Too Much Milk were positively associated with exclusive breastfeeding outcomes at 1 mo (b3 = 0.42) and 2 mo (b3 = 0.41). This was contrary to the direction of effect we expected when we hypothesized a priori that early breastfeeding problems would be associated with poorer breastfeeding outcomes.

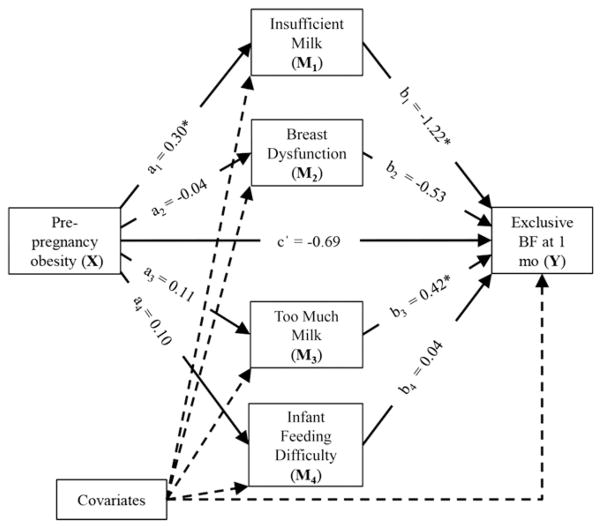

Our final hypothesis, the association between obesity and poor breastfeeding outcomes is mediated through early breastfeeding problems, was only true for 1 factor, Insufficient Milk. We observed a significant specific indirect effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding outcomes through problems related to Insufficient Milk among primiparous and multiparous women at both times (Table 6). No evidence was found that the association between obesity and breastfeeding outcomes was mediated through Breast Dysfunction, Too Much Milk, or Infant Feeding Difficulty. For example, for exclusive breastfeeding at 1 mo among primiparous women (Figure 2), obesity was positively associated with reporting of problems related to Insufficient Milk (a1 = 0.30; Table 5), which was negatively associated with exclusive breastfeeding (b1 = −1.22; Table 5). A bias-corrected CI for the indirect effect (a1b1 = −0.36; Table 6) did not contain zero (−0.73 to −0.09; Table 6), which indicated that there was significant mediation of the effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding at 1 mo through Insufficient Milk among primiparous women.

TABLE 6.

Path coefficients and 95% CIs for direct and indirect effects in adjusted mediation models of the association between obesity and exclusive BF among participants in the Infant Feeding Practices Study II1

| Primiparous (n = 550)

|

Multiparous (n = 1181)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path coefficient | 1-mo Point estimate2 | 95% CI | 2-mo Point estimate | 95% CI | 1-mo Point estimate | 95% CI | 2-mo Point estimate | 95% CI |

| a1b1 (indirect effect) | −0.36 | (−0.73, −0.09) | −0.23 | (−0.53, −0.02) | −0.30 | (−0.47, −0.17) | −0.32 | (−0.49, −0.19) |

| c′ (direct effect) | −0.69 | (−1.24, −0.14) | −0.70 | (−1.30, −0.11) | −0.34 | (−0.68, −0.002) | −0.1 | (−0.45, 0.25) |

| c (total effect) | −0.79 | (−1.3, −0.29) | −0.77 | (−1.33, −0.22) | −0.57 | (−0.88, −0.25) | −0.36 | (−0.68, −0.03) |

Models were adjusted for maternal age, household income, maternal marital status, maternal race/ethnicity, delivery mode, prenatal smoking status, previous BF experience, intended duration of BF, social knowledge of BF, social influence toward BF, maternal confidence in BF, and behavioral beliefs about BF. Models were reduced with the use of backward stepwise regression with covariates removed if they were not significant in the adjusted model Indirect path coefficients are all for factor I (Insufficient Milk). a1b1, indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator Insufficient Milk; BF, breastfeeding; c, total effect of the independent variable on the dependant variable; c′, direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

Point estimates are unstandardized B coefficients.

FIGURE 2.

Mediation of the relation between prepregnancy obesity and exclusive breastfeeding at 1 mo postpartum through early breastfeeding problems in primiparous women. ai estimates the effect of obesity on reporting specific early breastfeeding problems. bi estimates the effect of specific early breastfeeding problems on breastfeeding outcomes. c′ estimates the direct effect of obesity on breastfeeding outcomes, independent of the effect of obesity on early breastfeeding problems. *Denotes significant effects. See Table 5 for point estimates and P values. ai, effect of independent variable on mediator; bi, effect of mediator on dependent variable; BF, breastfeeding; c′, direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable; M, mediator.

Interestingly, among multiparous women, the indirect effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding at 2 mo mediated through Insufficient Milk was significant (a1b1 = −0.32; 95% CI: −0.49, −0.19; Table 6), but the direct effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding was not significant (c′ = −0.1; 95% CI: −0.45, 0.25). This indicates that the effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding at 2 mo in multiparous women was entirely mediated through problems related to Insufficient Milk.

Discussion

In a longitudinal cohort of US women, we found that early breastfeeding problems related to Insufficient Milk partially mediated the negative association between obesity and exclusive breastfeeding among both primiparous and multiparous women at 1 mo postpartum. At 2 mo postpartum the association between obesity and exclusive breastfeeding was again partially mediated through Insufficient Milk in primiparous women and completely mediated in multiparous women. These findings indicate that women with obesity are at risk of stopping exclusive breastfeeding because of early problems related to Insufficient Milk. Consequently, they may benefit from increased support in the early postpartum period.

Among multiparous women with obesity, although the total effect of the model was significant, the direct effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding at 2 mo postpartum was insignificant in mediation models that controlled for previous breastfeeding experience and other potential psychosocial confounders. This finding is important because it indicates that the negative effect of obesity on exclusive breastfeeding at 2 mo among these women is entirely mediated through early breastfeeding problems related to Insufficient Milk. This is especially interesting, given that multiparous women with obesity reported significantly lower social influence toward breastfeeding and lower maternal confidence in their ability to breastfeed until their intended duration than their normal-weight counterparts. This suggests that, despite perceived psychosocial disadvantages, the effect is entirely mediated through what could be a biological mechanism. Therefore, biological factors may be more important in the negative association between obesity and breastfeeding outcomes than psychosocial factors. However, these data are based on maternal self-report of early breastfeeding problems so we cannot rule out a psychosocial explanation for this result.

By comparing the magnitude of the direct and indirect effects with one another, we see that in primiparous women the indirect effect is consistently smaller than the direct effect, which implies that other important factors are involved in the association between obesity and exclusive breastfeeding that we have not identified in this analysis. However, among multiparous women, the indirect and direct effects are approximately equal at 1 mo postpartum, and the indirect effect alone is significant at 2 mo postpartum. This implies that Insufficient Milk is one of the most important factors involved in this association. This highlights the need for further exploration of the biological and psychosocial mechanisms of milk insufficiency in women with obesity and potential ways it can be ameliorated.

Although the only significant indirect mediating factor was named Insufficient Milk, it comprised 6 different problems, “took too long for milk to come in”; “baby did not gain/lost too much weight”; “nipples were sore, cracked, or bleeding”; “mom didn’t have enough milk for the baby”; “baby had trouble sucking or latching”; and “baby got distracted.” The first 2 problems relate to delayed onset of lactogenesis II, which occurs more commonly among women with obesity than among normal-weight women (13, 15). However, in this study we cannot tell whether the combination of all 6 problems reflects delayed onset of lactogenesis II or a real or perceived physiologic milk insufficiency.

Perceived milk insufficiency is commonly reported as a reason for cessation of any and exclusive breastfeeding (26, 27), and it is associated with lower breastfeeding self-efficacy scores (28, 29). Maternal confidence in her ability to breastfeed as long as her prenatal breastfeeding goal was assessed in the IFPS II questionnaires, but these questionnaires did not include the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale (30), a more comprehensive measure of a mother’s perceived ability to breastfeed her baby. Lower breastfeeding self-efficacy among obese women could explain the mediation of the association between obesity and poor exclusive breastfeeding outcomes through Insufficient Milk. If so, self-efficacy–enhancing strategies could improve breastfeeding outcomes in women with obesity.

In a recent cross-sectional study of primiparous women in China, Lou et al. (31) found that, among mothers who weaned because of insufficient milk supply, more than one-half reported that this occurred during the first 2 d postpartum. This early perception of insufficient milk may reflect a lack of knowledge of the biological process of lactation. Milk production is limited in the first few days postpartum; however, mothers who do not know that this is physiologically normal may perceive that they have insufficient milk. If this were the case in the IFPS II sample, increased education about the biology of lactation and what to expect in the early days postpartum could help to improve breastfeeding outcomes.

Potential biological explanations for true milk insufficiency in women with obesity include a diminished prolactin response to suckling (11) and declining insulin secretion (32). Preliminary research by Nommsen-Rivers et al. (32), suggests that, despite insulin resistance, declining insulin secretion may be an important contributor to low milk supply among women with obesity. In their recent analyses of the human milk fat layer transcriptome, Lemay et al. (33) discovered that genes encoding insulin signaling proteins are up-regulated during the transition from colostral to transitional lactation. On the basis of their RNA sequencing study, Lemay et al. (33) proposed that women with decreased insulin sensitivity experience a slower increase in milk output as a result of the overexpression of a specific protein (protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, F), which could potentially be used in the future as a biomarker to link insulin resistance with insufficient milk supply. The role of insulin in breast milk production is a promising avenue of research that may help explain the association between obesity and poor breastfeeding outcomes and warrants further investigation.

Our results add to previous research with the use of the same data set that described an increased prevalence of disrupted lactation and increased odds of early weaning among obese participants in the IFPS II (18). This present analysis builds on this work by testing for mediation. We took advantage of the temporal nature of the IFPS II and modeled the problems that women reported experiencing in the first 2 wk postpartum as mediators of outcomes at 1 and 2 mo. This study design allowed us to test mediation of the association between obesity and breastfeeding outcomes through early breastfeeding problems.

This analysis also builds on the work of Wagner et al. (20), who studied primiparous women only. Our results indicate that problems related to Insufficient Milk are also negatively associated with exclusive breastfeeding outcomes in multiparous women with obesity. The 2 categories of concerns found to be most important by Wagner et al. (20) were infant feeding difficulty and milk quantity. Their category milk quantity included concerns that the mother is not producing enough milk or the infant is not getting sufficient milk, similar to our factor I, Insufficient Milk. Like Wagner et al. (20), we found that Insufficient Milk was an important factor in the association between obesity and breastfeeding outcomes. However, we found no association with or mediation through our factor IV, Infant Feeding Difficulty and breastfeeding outcomes.

Our findings that conflict with our hypotheses have biological explanations. Our a priori hypothesis that early breastfeeding problems would be associated with poorer breastfeeding outcomes was developed before conducting our factor analysis. As such, we did not have hypotheses about the association of each individual factor with breastfeeding outcomes. Not surprisingly, among primiparous women with obesity, early problems related to Too Much Milk were positively associated with breastfeeding outcomes, meaning that women who felt they had too much milk in the early postpartum period were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding at later times. Multiparous women with obesity, in contrast, were less likely to report problems related to Breast Dysfunction or Too Much Milk. The reduced reporting of Too Much Milk problems among women who were more likely to report Insufficient Milk problems makes intuitive sense.

The strengths of this study include the large sample size of the IFPS II, our novel use of factor analysis to create continuous variables for use in mediation analyses, and our focus on early postpartum problems with breastfeeding. Our focus on problems that occur in the first 2 wk postpartum is clinically valuable because women with obesity who report specific problems at this time could be targeted for additional support. The use of self-report measures to calculate BMI is often considered a limitation because weight is often under-reported and with greater frequency among heavier than lighter women. However, in this analysis we compared normal-weight women with women with obesity which should reduce the potential bias caused by under-reporting of obesity because these 2 BMI categories are likely to be distinct. In addition, under-reporting of weight would most likely result in overweight women being misclassified as normal-weight in our analysis. If overweight women also experienced poor breastfeeding outcomes mediated by early breastfeeding problems, misclassifying them into our normal-weight group would have biased our results toward the null and, thus, should not have changed the inferences we have drawn.

There are limitations inherent to the IFPS II that must be considered when interpreting these findings. Women were offered a predefined list of potential problems that they may have had in the first 2 wk postpartum. It is unknown whether this list captures all potential problems that obese and normal-weight women experienced in the early postpartum period. Qualitative research would be beneficial for identifying additional problems and for understanding whether they differ by obesity status. This research is also limited by question design. Women were asked to select all breastfeeding problems that applied to them but were not asked to check if they did not apply. This means that in cases in which no breastfeeding problems were selected (n = 9), we cannot tell whether these women did not experience any breastfeeding problems or if they simply skipped the question. However, this number was small and unlikely to have affected our results. In addition, the IFPS II sample is not nationally representative (22). Compared with a nationally representative sample, women participating in the IFPS II were more likely to be older, middle-income, white, employed, and more educated.

Another limitation relates to the inability to control for potential confounding variables about which we lack data. One such confounding factor is smoking behavior at the time periods of breastfeeding described here. Participants in this study were asked about smoking behavior on the prenatal questionnaire, adminis-teredinthethirdtrimesterofpregnancy.Participantswerealsoasked about smoking at 3 mo postpartum, but this is after the 1- and 2-mo breastfeeding durations assessed in this analysis and may or may not reflect behaviors during the early postpartum period. It is possible that some women who reported being nonsmokers prenatally had quit smoking for the duration of their pregnancy and resumed smoking early postpartum. This is important because smoking is associated with poorer breastfeeding outcomes (34, 35), an association that likely has a multifactorial cause. It was hypothesized that smoking impairs breastfeeding duration by suppressing prolactin secretion (36), reducing the volume of breast milk produced, and potentially resulting in insufficient milk. Studies suggest that almost one-half of regular smokers who quit during pregnancy resumed smoking by 5–6 mo postpartum (37, 38). However, we do not have data on the number of women in our sample who resumed smoking before 3 mo postpartum. As a result, it is possible that we have underestimated the effect of smoking in our analyses.

A statistical limitation specific to this study is that there is currently no good way to estimate the proportion of the total effect of obesity on breastfeeding outcomes explained indirectly through early breastfeeding problems. This is because the indirect and total effects are scaled differently when dealing with dichotomous outcomes with the use of the PROCESS macro. The path from the independent variable to the mediator is estimated with the use of ordinary least squares regression, and the path from the mediator to the dependent variable is estimated with the use of logistic regression, so the total effect is not equal to the sum of the direct and indirect effects. However, we can still determine whether the direct and indirect effects are significant. This issue is only problematic because the difference between the total and the direct effect cannot be used as a substitute for the indirect effect.

In conclusion, these findings are clinically important because they highlight a group of women that may benefit from additional breastfeeding support early postpartum, namely women with obesity who report that they experience the problems that grouped in the Insufficient Milk factor. It could be worthwhile to question mothers postpartum about their early breastfeeding problems to identify women at risk of suboptimal breastfeeding outcomes. Early breastfeeding cessation is of particular public health concern because cessation of any or exclusive breastfeeding within the first 2 mo postpartum reduces the total dose of breastfeeding that a child receives by a greater amount than cessation by 6 mo postpartum, an outcome commonly reported in the literature.

Acknowledgments

EJOS, CGP, and KMR designed the research; EJOS performed the statistical analysis, wrote the paper, and had primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by an International Fulbright Science and Technology Award (to EJOS).

Author disclosures: EJ O’Sullivan, CG Perrine, and KM Rasmussen, no conflicts of interest.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Abbreviations used: ai, effect of independent variable on mediator; bi, effect of mediator on dependent variable; IFPS II, Infant Feeding Practices Study II; PIR, poverty income ratio.

References

- 1.Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:341–7. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilson JA, Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. Maternal obesity and breast-feeding success in a rural population of white women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:1371–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.6.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li R, Jewell S, Grummer-Strawn L. Maternal obesity and breast-feeding practices. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:931–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauff LE, Leonard SA, Rasmussen KM. Associations of maternal obesity and psychosocial factors with breastfeeding intention, initiation, and duration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:524–34. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.071191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGuire S U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. The surgeon general’s call to action to support breastfeeding. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. 2011. Adv Nutr. 2011;2:523–4. doi: 10.3945/an.111.000968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020: maternal, infant, and child health: objectives [Internet] Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human Services; [cited 2015 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu SY, Kim SY, Bish CL. Prepregnancy obesity prevalence in the United States, 2004–2005. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13:614–20. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0388-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker JL, Michaelsen KF, Sorensen TIA, Rasmussen KM. High pre-pregnant body mass index is associated with early termination of full and any breastfeeding in Danish women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:404–11. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donath SM, Amir LH. Maternal obesity and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: data from the longitudinal study of Australian children. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4:163–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. Prepregnant overweight and obesity diminish the prolactin response to suckling in the first week postpartum. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e465–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman DJ, Perez-Escamilla R. Identification of risk factors for delayed onset of lactation. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:450–4. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilson JA, Rasmussen KM, Kjolhede CL. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with poor lactation outcomes among white, rural women independent of psychosocial and demographic correlates. J Hum Lact. 2004;20:18–29. doi: 10.1177/0890334403261345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brownell E, Howard CR, Lawrence RA, Dozier AM. Delayed onset lactogenesis II predicts the cessation of any or exclusive breastfeeding. J Pediatr. 2012;161:608–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nommsen-Rivers LA, Chantry CJ, Peerson JM, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG. Delayed onset of lactogenesis among first-time mothers is related to maternal obesity and factors associated with ineffective breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:574–84. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, Cohen RJ. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112:607–19. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews MK. Developing an instrument to assess infant breast-feeding behaviour in the early neonatal period. Midwifery. 1988;4:154–65. doi: 10.1016/s0266-6138(88)80071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stuebe AM, Horton BJ, Chetwynd E, Watkins S, Grewen K, Meltzer-Brody S. Prevalence and risk factors for early, undesired weaning attributed to lactation dysfunction. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2014;23:404–12. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2013.4506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott JA, Binns CW, Oddy WH. Predictors of delayed onset of lactation. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3:186–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wagner EA, Chantry CJ, Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA. Breastfeeding concerns at 3 and 7 days postpartum and feeding status at 2 months. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e865–75. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kronborg H, Vaeth M, Rasmussen KM. Obesity and early cessation of breastfeeding in Denmark. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23:316–22. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fein SB, Labiner-Wolfe J, Shealy KR, Li RW, Chen J, Grummer-Strawn LM. Infant Feeding Practices Study II: study methods. Pediatrics. 2008;122:S28–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1315c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merrill RM, Richardson JS. Validity of self-reported height, weight, and body mass index: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2001–2006. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connor Gorber S, Tremblay M, Moher D, Gorber B. A comparison of direct vs. self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2007;8:307–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 1. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCann MF, Baydar N, Williams RL. Breastfeeding attitudes and reported problems in a national sample of WIC participants. J Hum Lact. 2007;23:314–24. doi: 10.1177/0890334407307882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gatti L. Maternal perceptions of insufficient milk supply in breastfeeding. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008;40:355–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarter-Spaulding DE, Kearney MH. Parenting self-efficacy and perception of insufficient breast milk. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2001;30:515–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2001.tb01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otsuka K, Dennis CL, Tatsuoka H, Jimba M. The relationship between breastfeeding self-efficacy and perceived insufficient milk among Japanese mothers. J Obstet Gynecik Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:546–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dennis CL, Faux S. Development and psychometric testing of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale. Res Nurs Health. 1999;22:399–409. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199910)22:5<399::aid-nur6>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lou Z, Zeng G, Huang L, Wang Y, Zhou L, Kavanagh KF. Maternal reported indicators and causes of insufficient milk supply. J Hum Lact. 2014;30:466–73. doi: 10.1177/0890334414542685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nommsen-Rivers L, Glueck C, Huang B, Wang P, Dolan L. Lactation sufficiency is predicted by fasting plasma glucose at 1 month postpartum. FASEB J. 2014;28:131.1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lemay DG, Ballard OA, Hughes MA, Morrow AL, Horseman ND, Nommsen-Rivers LA. RNA sequencing of the human milk fat layer transcriptome reveals distinct gene expression profiles at three stages of lactation. PLoS One. 2013:e67531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dieterich CM, Felice JP, O’Sullivan E, Rasmussen KM. Breastfeeding and health outcomes for the mother-infant dyad. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2013;60:31–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thulier D, Mercer J. Variables associated with breastfeeding duration. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38:259–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bahadori B, Riediger ND, Farrell SM, Uitz E, Moghadasian MF. Hypothesis: Smoking decreases breast feeding duration by suppressing prolactin secretion. Med Hypotheses. 2013;81:582–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lelong N, Kaminski M, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Bouvier-Colle MH. Postpartum return to smoking among usual smokers who quit during pregnancy. Eur J Public Health. 2001;11:334–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/11.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solomon LJ, Higgins ST, Heil SH, Adger GJB, Thomas CS, Ernstein IMB. Predictors of postpartum relapse to smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:224–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]