Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Intravenous thrombolysis remains the mainstay treatment for acute ischemic stroke. One of the most feared complications of the treatment is thrombolysis-related symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH), which occurs in nearly 6% of patients and carries close to 50% mortality. The treatment options for sICH are based on small case series and expert opinion, and the efficacy of recommended treatments is not well known.

OBJECTIVE

To provide an overview on the rationale and mechanism of action of potential treatments for sICH that may reverse the coagulopathy before hematoma expansion occurs.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

Evidence-based peer-reviewed articles, including randomized trials, case series and reports, and retrospective reviews, were identified in a PubMed search on the mechanism of action of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and the rationale of various potential treatments using the coagulation cascade as a model. The search encompassed articles published from January 1, 1990, through February 28, 2014.

FINDINGS

The current treatments may not be sufficient to reverse coagulopathy early enough to prevent hematoma expansion and improve the outcome of thrombolysis-related hemorrhage.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Given the mechanism of action of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, clinical studies could include agents with a fast onset of action, such as prothrombin complex concentrate, recombinant factor VIIa, and ε-aminocaproic acid, as potential therapeutic options.

Intravenous thrombolytic therapy with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) is the mainstay of treatment for acute ischemic stroke when administered within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.1 Although intravenous rtPA improves clinical outcomes at 3 months, its widespread use has been limited by concerns of hemorrhagic complications associated with treatment. The most feared complication is symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage(sICH), which has been associated with close to 50% mortality.2 There has been wide variability in the reported rates of sICH, although most recent case series and postmarketing surveillance studies3 have shown an incidence lower than the 6% observed in the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke t-PA study. Treatment options for sICH are based on small case series and expert opinions, and the efficacy of recommended treatments is not well known. In this review, the definitions and epidemiologic characteristics of sICH are discussed, with a focus on the rationale and options for treatment. Evidence-based peer-reviewed articles on sICH were identified in a PubMed search conducted between December 15, 2013, and February 28, 2014. The search encompassed articles published from January 1, 1990, through February 28, 2014.

sICH After Thrombolysis: Definitions

Evaluating the incidence and consequences of sICH has been challenging given the variable definitions used in different studies in terms of clinical and imaging characteristics; all definitions require the presence of blood products on a posttreatment computed tomography (CT) of the head. Each definition of sICH has variable associations with mortality, and high interrater variability for each definition makes comparability across studies difficult to establish.4 The radiologic appearance of hemorrhage after ischemic stroke was defined in the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study II (ECASS II)5 and includes hemorrhagic infarction classifications HI 1 and HI 2 and parenchymal infarction classifications PH 1 and PH 2 (Table). The ECASS II classification is one of the most widely used sICH definitions and does not require knowing the presence of clinical decline, particularly because only the PH2 class of hemorrhage has been significantly associated with poor outcomes.6 The most commonly adopted definitions, which include clinical and imaging data, are derived from landmark clinical trials,3,5 as well as postmarketing surveillance studies such as Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST)3 and Get With the Guidelines–Stroke.7 Each definition has its own advantages and disadvantages. For example, the SITS-MOST definition appeared to have the best ability to predict mortality, and the ECASS II definition has the highest interrater correlation.8 With the lack of consensus defining sICH, it may be challenging to determine whether medical treatment for sICH is effective.

Table.

Radiologic Classification Schemes for Postthrombolysis Intracranial Hemorrhage

| Hemorrhage Classification |

Definition |

|---|---|

| HI 1 | Small petechial hemorrhage without space-occupying effect |

| HI 2 | More confluent petechial hemorrhage without space-occupying effect |

| PH 1 | Hemorrhage in <30% of the infarcted area with mild space-occupying effect |

| PH 2 | Hemorrhage in <30% of the infarcted area with mild space-occupying effect |

Abbreviations: HI, hemorrhagic infarction; PH, parenchymal hematoma.

Prevention and Management of sICH

The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines1 for care after thrombolysis include measures to reduce the potential for sICH, such as blood pressure control (<180/105 mm Hg after treatment) and avoiding the use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents in the first 24 hours of treatment. The definitions of sICH include variable time periods from initiation of intravenous rtPA to detection of hemorrhage on imaging; the timing of sICH has not been well characterized pathobiologically. For example, it has not been well described if sICH starts during the infusion, 1 hour after the infusion, or at a later time. Furthermore, the associated time frame of hematoma expansion after sICH is unknown.

The recommended management in the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association1 acute treatment guidelines includes replacement of coagulation factors and platelets, with the guidelines acknowledging limited evidence to support the details of care. The paucity of data on how to treat sICH has led to substantial variability in the treatment algorithm used, along with whether any treatment should be offered. In Get With the Guidelines–Stroke,4 55% of the patients received any treatment to potentially reverse the effect of intravenous rtPA, with wide variability in the use of fresh frozen plasma (FFP), cryoprecipitate, vitamin K1, or other agents; moreover, approximately 40% of the patients with sICH had continued bleeding. The role of withdrawal of care, a leading cause of death in patients with hemorrhagic stroke, was not well characterized in this or other studies. Immediate surgical treatment is usually avoided in sICH because of the high perioperative risk associated with intravenous rtPA-related coagulopathy; the role of surgical hematoma evacuation after intravenous rtPA-associated coagulopathy resolves also has not been well characterized. The lack of consensus on how to manage sICH as well as continued poor outcomes pose important challenges in clinical research on acute stroke and have been additional driving forces in the development of novel therapies for acute stroke with new thrombolytic agents and endovascular strategies.

Treatment Options

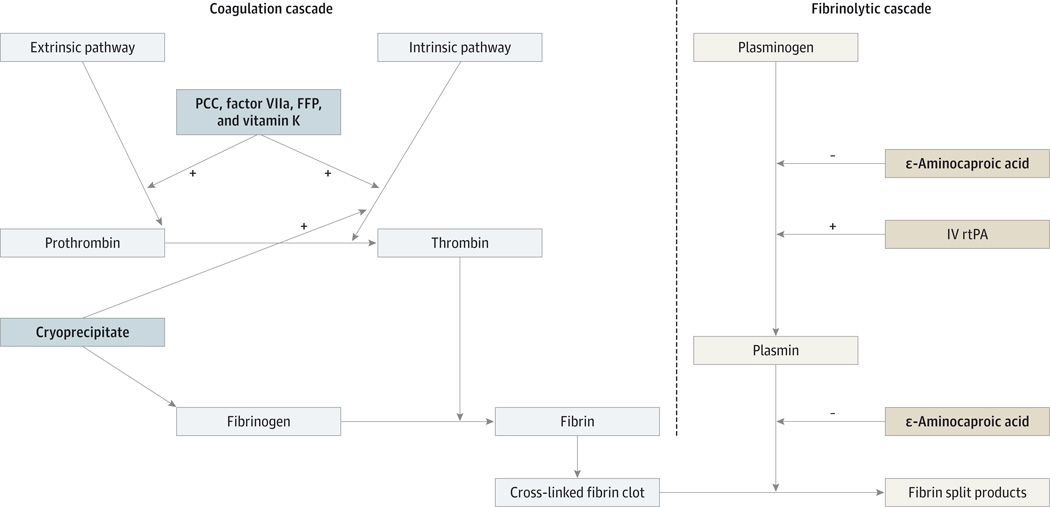

Improving the outcome of patients with sICH is of paramount importance because it may reduce the hesitancy of physicians other than neurologists to be more aggressive in treating with intravenous rtPA within the appropriate time window. Proposed treatments to prevent hematoma expansion and neurologic worsening in sICH include vitamin K, FFP, cryoprecipitate, prothrombin complex concentrates, platelet transfusions, and ε-aminocaproic acid. We review the mechanism of action of rtPA and the potential benefit of each treatment strategy (Figure). Most of the data on the above treatments were extrapolated from warfarin-related intracranial hemorrhage because intravenous rtPA-related sICH has not been evaluated. The mechanism of action of intravenous rtPA differs from that of warfarin; thus, reversing the effects in each treatment may require a different therapeutic approach. There is also a unique aspect of how sICH differs from warfarin-related ICH in that sICH is diagnosed after a second CT scan is performed to evaluate clinical deterioration or as per protocol 24 to 36 hours after thrombolysis and before starting antithrombotics. Clinical deterioration may not occur at the onset of thrombolysis-related sICH because the hemorrhage typically starts in infarcted brain tissue; as such, sICH may occur in patients with already substantial neurologic deficits. The new symptoms may be detected several hours later and are attributable to symptomatic mass effector increased intracranial pressure. Early diagnosis and aggressive reversal of coagulopathy may therefore be required before significant changes in the neurologic examination occur.

Figure.

Coagulation and Fibrinolytic Pathways Showing the Mode of Action of Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Treatment

FFP indicates fresh frozen plasma; IV, intravenous; PCC, prothrombin complex concentrate; rtPA, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator;

+, activation; and −, inhibition. Treatments are indicated with boldface type.

rtPA Mechanism of Action

Intravenous rtPA produces local thrombolysis by converting plasminogen into plasmin, which in turn degrades fibrin into fibrin split products. Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator is short acting, with more than 50% cleared 5 minutes after cessation of the infusion and approximately 80% cleared after 10 minutes. Clearance of rtPA is primarily through the liver, and it is excreted in the urine. Despite rapid clearance, the effect of rtPA on the coagulation profile entails prolongation of the prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times, as well as a reduction in fibrinogen levels, and may last 24 hours or more from the infusion time.6 Among the coagulation profile components, the degree of reduction in fibrinogen may best correlate with the degree of thrombolysis and hemorrhage risk; for example, the occurrence of sICH appears to be higher when there is a reduction in fibrinogen by more than 200 mg/dL 6 hours after treatment.9 Randomized clinical trials2 showed that an rtPA dose of 0.9 mg/kg (maximum dose, 90 mg) is safe and effective in achieving thrombolysis.

The occurrence of sICH after intravenous administration of rtPA may not be solely related to the coagulopathy induced by thrombolytic therapy; it also may be associated with disruption of the blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier consists of tight junctions that facilitate selective transport and the basal lamina that prevents extravasation of cellular blood elements from the arterioles and capillaries into the brain parenchyma. Animal studies10 show that hemorrhagic transformation is associated with breakdown of the basal lamina, which may be caused by the release and activation of metalloproteinases because of ischemia.11 Reperfusion after thrombolysis may lead to injury through activation of metalloproteinases independently12 and through formation of oxygen free radicals.13 In animal models,14 the incidence of sICH can be significantly reduced with inhibition of metalloproteinase activation or oxygen free radical formation, further supporting this mechanism of action. Thus, physicians selecting any treatment aimed at preventing or ameliorating the consequences of sICH need to consider not only the coagulopathy caused by thrombolysis but also the integrity of the blood-brain barrier.

Fresh Frozen Plasma

Fresh frozen plasma refers to the plasma collected from blood donors and frozen at −18°C; it contains all endogenous procoagulant and anticoagulant proteins in the same relative proportions that prevail in the donor’s plasma. These factors can potentially drive fibrin formation by activating the coagulation cascade, thereby countering the increased activity of plasmin associated with rtPA. Fresh frozen plasma has to be administered slowly in large intravenous volumes to prevent volume overload and other transfusion-related reactions. The requirement of a large volume of infusion also increases the time for this treatment to reverse coagulopathy in patients with ongoing hemorrhage. In patients with warfarin-related ICH, FFP takes a median of 30 hours to return the international normalized ratio to within the reference range,15 with a low risk for major transfusion reactions (eg, transfusion-related lung injury, infection, and anaphylaxis). Although the mechanisms of coagulopathy in thrombolysis-associated sICH and warfarin-related ICH differ, the long time period for reversal applies to both diseases and may allow for hematoma expansion and clinical deterioration before correcting the coagulopathy.

Vitamin K

Vitamin K promotes liver synthesis of factors II, VII, IX, and X, as well as the endogenous anticoagulants proteins C and S. Although vitamin K treatment is relatively safe, it takes several hours for the liver to synthesize those factors and thus is not an ideal monotherapy to urgently reverse coagulopathy. Vitamin K, given at a dose of 10 mg intravenously, can reverse coagulopathy in patients with warfarin-related ICH within 12 to 24 hours,16 with minimal risk of an anaphylactic reaction (1 of 3000 patients). However, in thrombolysis-related hemorrhage, the main mechanism of coagulopathy is not related to the deficiency of the above factors but rather to the reduction in fibrinogen. Thus, because of the relatively prolonged time for coagulopathy reversal and ineffective replenishment of fibrinogen levels, vitamin K may not be the ideal monotherapy in patients with sICH. However, use of vitamin K could potentiate other treatments because it may activate both the extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation pathways, promoting later conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin, reducing plasmin activity, and potentially stabilizing a parenchymal hematoma.

Prothrombin Complex Concentrates

Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) are a combination of the vitamin K–dependent factors II, VII, IX, and X along with proteins C and S. The concentrates activate both the intrinsic coagulation pathway via factor IX and the extrinsic pathway via factor VII. The end result of both pathways is the activation of factor X to factor Xa, which then converts prothrombin into thrombin, which in turn converts fibrinogen into a fibrin clot. Prothrombin complex concentrates are used in warfarin-related ICH and have been shown17 to correct the international normalized ratio in less than 30 minutes after an infusion without requiring large intravenous volumes. Another advantage of PCCs is that they do not require the administration of large volumes of intravenous fluids. Although the mechanism of action of rtPA does not involve inhibition of the coagulation factors found in PCCs, the use of PCCs in the treatment of sICH offers a relatively quick way to activate both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, which may aid in the later conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin. However, because rtPA reduces fibrinogen levels, it is possible that fibrinogen would also need to be administered to patients for PCCs to help in that conversion. The potential for reversing coagulopathy with PCCs should include consideration of the low risk (approximately1%) of thrombotic events with such treatment, especially in a patient who has just experienced an ischemic stroke.18

ε-Aminocaproic Acid

ε-Aminocaproic acid inhibits fibrinolysis by preventing the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, as well as directly inhibiting the proteolytic activity of plasmin, resulting in clot stabilization. ε-Aminocaproic acid has a relatively short half-life (2 hours) and exhibits its peak action approximately 3 hours after administration. In patients with rtPA-related sICH, there is an increase in plasmin activity and a reduction in fibrinogen as a result of fibrinolysis. ε-Aminocaproic acid has been shown19 not only to inhibit fibrinolysis but also to increase fibrinogen levels that are reduced in patients with a sICH. In one case report,20 ε-aminocaproic acid monotherapy was successful in stabilizing the hematoma in a patient with a sICH. With its relatively fast peak action and efficacy in inhibiting fibrinolysis, ε-aminocaproic acid could be considered in the treatment of sICH. Potential risks of such treatment include a hypothetical increase in thrombotic events, although meta-analyses21 do not support this concern.

Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate is prepared from FFP thawed at approximately 4°C and consists of fibrinogen (approximately 200 mg per unit of cryoprecipitate), factor VIII (approximately 100 U per unit of cryoprecipitate), and von Willebrand factor. Cryoprecipitate has a fast onset of action and quickly increases fibrinogen levels. Because it also contains factor VIII, cryoprecipitate activates the intrinsic pathway, allowing conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin, stabilizing coagulopathy, and having the potential for preventing hematoma expansion. Typical doses of cryoprecipitate (8–12 U)increase fibrinogen levels by only approximately 50 to 70 mg/dL22; a decrease in fibrinogen levels of greater than 200 mg/dL is a risk factor for sICH. It is thus likely that 10 U of cryoprecipitate may not be sufficient to replenish the reduction of fibrinogen caused by rtPA when a sICH occurs. In one study,6 50% of the patients who received the recommended doses of cryoprecipitate developed hematoma expansion.

Platelet Transfusion

Plasmin initially activates platelets, an effect mediated by an increase in local calcium concentrations, followed later by platelet inhibition mediated by adenosine diphosphate,23 as well as decreased expression of platelet glycoprotein Ib.24 The American Heart Association/American Stroke Association1 guidelines recommend using platelet transfusions in the treatment of sICH; however, the role of platelet dysfunction in the mechanism of sICH formation is not well known.

Recombinant Factor VIIa

Recombinant factor VIIa is a vitamin K–dependent glycoprotein that promotes homeostasis by activating the extrinsic coagulation cascade, thus facilitating the formation of thrombin, which in turn converts fibrinogen into fibrin. Recombinant factor VIIa has a short half-life(2.3 hours) and a meantime of 6 hours to reverse the international normalized ratio in warfarin-related coagulopathy.25 In patients with spontaneous ICH, recombinant factor VIIa is not routinely recommended because of a lack of clinical benefit and increased risk for thrombotic events.26 There have been no reports on the use of recombinant activated factor VIIa in patients with thrombolysis-related sICH. With its fast onset of action, recombinant activated factor VIIa could potentially rapidly enhance conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin, thus stabilizing the hematoma. However, this possible benefit should be weighed against the risk for thrombotic events with such treatment.

Surgical Treatment

Clot evacuation in ICH can be considered in patients with lobar hemorrhage within 1 cm from the surface.24 Data from the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue-Plasminogen Activator (tPA) for Occluded Coronary Arteries study27 showed that, in patients with myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytic therapy, the outcome of those with ICH improved after surgical treatment vs nonsurgical treatment. Because large infarct size is a risk factor for sICH after intravenous administration of rtPA, patients with a stroke (as opposed to a myocardial infarction) may have significant underlying cerebral injury that could mitigate any potential for surgery. Surgeons may be reluctant to perform a craniotomy in the acute setting while the patient is coagulopathic owing to the difficulty with achieving hemostasis in the operative field. Less is known about surgical options after coagulopathy has resolved, including the potential benefit of hemicraniectomy. After resolution of coagulopathy, patients with sICH could be considered for further trials to determine the risks and benefits of surgery.

Conclusions

Although there are no established treatments for reversing coagulopathy in patients with sICH, the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association guidelines recommend replacement of coagulation factors and platelets using 10 U of cryoprecipitate and 6 to 8 U of platelets.6 The scientific evidence for this recommendation is based on empirical data and extrapolation from other organ systems; the unanswered questions on efficacy may explain the wide variability observed in clinical practice. Because the coagulopathy related to rtPA may last up to 24 hours, early and sustained reversal is necessary before hematoma expansion and neurologic deterioration occurs. Aggressive approaches must be weighed against the potential for worsening thrombosis. Given the mechanism of action of intravenous rtPA, future clinical studies could include multimodal therapy with agents with a fast onset of action, such as PCCs, recombinant factor VIIa, and ε-aminocaproic acid. Clinical prediction scores for sICH may identify patients who should undergo neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging or a CT of the head before the 24-hour standard time frame to provide early treatment. Treatment options for thrombolysis-related sICH may also need to be tested in combination with neuroprotectant agents, particularly those that aim to salvage the integrity of the neurovascular unit and thus the blood-brain barrier. An effective treatment for sICH may increase the usefulness of intravenous rtPA in treating acute ischemic stroke, particularly for physicians other than neurologists.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Willey had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: All authors.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Yaghi, Willey.

Drafting of the manuscript: All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Eisenberger, Willey.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Eisenberger, Willey.

Study supervision: Willey.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP, Jr, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870–947. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e318284056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–1588. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Dávalos A, et al. SITS-MOST Investigators. Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):275–282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein JN, Marrero M, Masrur S, et al. Management of thrombolysis-associated symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Neurol. 2010;67(8):965–969. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, et al. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;352(9136):1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matrat A, De Mazancourt P, Derex L, et al. Characterization of a severe hypofibrinogenemia induced by alteplase in two patients thrombolysed for stroke. Thromb Res. 2013;131(1):e45–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon BK, Saver JL, Prabhakaran S, et al. Risk score for intracranial hemorrhage in patients with acute ischemic stroke treated with intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator. Stroke. 2012;43(9):2293–2299. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gumbinger C, Gruschka P, Böttinger M, et al. Improved prediction of poor outcome after thrombolysis using conservative definitions of symptomatic hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43(1):240–242. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.623033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trouillas P1, Derex L, Philippeau F, et al. Early fibrinogen degradation coagulopathy is predictive of parenchymal hematomas in cerebral rt-PA thrombolysis: a study of 157 cases. Stroke. 2004;35(6):1323–1328. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000126040.99024.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamann GF, del Zoppo GJ, von Kummer R. Hemorrhagic transformation of cerebral infarction—possible mechanisms. Thromb Haemost. 1999;82(suppl 1):92–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.del Zoppo GJ, von Kummer R, Hamann GF. Ischaemic damage of brain microvessels: inherent risks for thrombolytic treatment in stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65(1):1–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujimura M, Gasche Y, Morita-Fujimura Y, Massengale J, Kawase M, Chan PH. Early appearance of activated matrix metalloproteinase-9 and blood-brain barrier disruption in mice after focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Brain Res. 1999;842(1):92–100. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01843-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters O, Back T, Lindauer U, et al. Increased formation of reactive oxygen species after permanent and reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18(2):196–205. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199802000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lapchak PA, Chapman DF, Zivin JA. Metalloproteinase inhibition reduces thrombolytic (tissue plasminogen activator)-induced hemorrhage after thromboembolic stroke. Stroke. 2000;31(12):3034–3040. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.12.3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee SB, Manno EM, Layton KF, Wijdicks EF. Progression of warfarin-associated intracerebral hemorrhage after INR normalization with FFP. Neurology. 2006;67(7):1272–1274. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238104.75563.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson HG, Baglin T, Laidlaw SL, Makris M, Preston FE. A comparison of the efficacy and rate of response to oral and intravenous vitamin K in reversal of over-anticoagulation with warfarin. Br J Haematol. 2001;115(1):145–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pabinger I, Brenner B, Kalina U, Knaub S, Nagy A, Ostermann H. Beriplex P/N Anticoagulation Reversal Study Group. Prothrombin complex concentrate (Beriplex P/N) for emergency anticoagulation reversal: a prospective multinational clinical trial. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(4):622–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dentali F, Marchesi C, Pierfranceschi MG, et al. Safety of prothrombin complex concentrates for rapid anticoagulation reversal of vitamin K antagonists: a meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106(3):429–438. doi: 10.1160/TH11-01-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson GH, Florentino-Pineda I, Armstrong DG, Poe-Kochert C. Fibrinogen levels following Amicar in surgery for idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32(3):368–372. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000253962.24179.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.French KF, White J, Hoesch RE. Treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage with tranexamic acid after thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17(1):107–111. doi: 10.1007/s12028-012-9681-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutton B, Joseph L, Fergusson D, Mazer CD, Shapiro S, Tinmouth A. Risks of harms using antifibrinolytics in cardiac surgery: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised and observational studies. BMJ. 2012;345:e5798. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danés AF, Cuenca LG, Bueno SR, Mendarte Barrenechea L, Ronsano JB. Efficacy and tolerability of human fibrinogen concentrate administration to patients with acquired fibrinogen deficiency and active or in high-risk severe bleeding. Vox Sang. 2008;94(3):221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2007.01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Penny WF, Ware JA. Platelet activation and subsequent inhibition by plasmin and recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator. Blood. 1992;79(1):91–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stricker RB, Wong D, Shiu DT, Reyes PT, Shuman MA. Activation of plasminogen by tissue plasminogen activator on normal and thrombasthenic platelets: effects on surface proteins and platelet aggregation. Blood. 1986;68(1):275–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman WD, Brott TG, Barrett KM, et al. Recombinant factor VIIa for rapid reversal of warfarin anticoagulation in acute intracranial hemorrhage. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79(12):1495–1500. doi: 10.4065/79.12.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, III, Anderson C, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2010;41(9):2108–2129. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3181ec611b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahaffey KW, Granger CB, Sloan MA, et al. Neurosurgical evacuation of intracranial hemorrhage after thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: experience from the GUSTO-I trial: Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue-Plasminogen Activator (tPA) for Occluded Coronary Arteries. Am Heart J. 1999;138(3, pt 1):493–499. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]