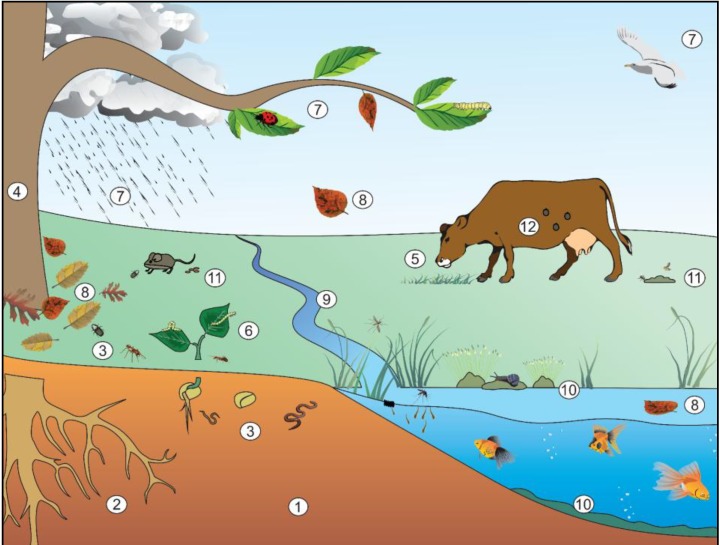

Figure 1.

Simplified view of complex lifestyle of Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) in different environmental niches. Vertebrates and invertebrates are only examples of a much wider range of possible hosts. The soil (1) is usually the largest reservoir of Bt, because it receives the highest amount of propagules from other environments. From it, Bt can colonize the rhizosphere (2) feeding on roots exudates. If eaten by soil invertebrates such as worms, insects and nematodes (3), Bt can infect in a paratenic way, colonizing the gut and feces, or in a pathogenic way, killing the host and growing in the cadaver. Thus Bt is re-introduced into the environment through these two ways. Rhizosphere colonization favors endophytic colonization (4) which protects the plant from some herbivores, while helps Bt to proliferate in plant tissues and infecting herbivores in paratenic (5) or pathogenic (6) ways. Besides endophytism, Bt can reach the surface of the plants from the soil due to the germination process, by splashes of rain water, and through the feces of animals that carry it, such as insects and birds (7). The infected fallen leaves can re-introduce Bt in soil and water (8). The rain may also carry the Bt to water bodies from soil and plants (9). In water the Bt can infect and proliferate in vertebrates or invertebrates and persiste in this environment by associating with substrates as aquatic plants and sediments (10). Faeces from animals that feed on contaminated plants or insects can serve as a source of nutrients for Bt growth, and they can act as a source of infection for coprophagous (11). It is known that ticks and mites are also Bt hosts (12), but the natural mechanism of infection is unknown. It is possible to observe a wide range of strategies for Bt occupy different niches and disperse in environment with or without causing disease.