Deep brain stimulation is an effective and safe treatment option for a variety of medical conditions including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and essential tremor, and carries a Humanitarian Device Exemption from the FDA for the treatment of dystonia and obsessive compulsive disorder. Recent work has demonstrated the possibility of utilizing deep brain stimulation of the fornix (DBS-f) for the treatment of AD1–3. We report on a patient with AD who was implanted with DBS-f and subsequently demonstrated asymptomatic bilateral encephalomalacia at the cortical entry sites of the leads.

Case Report

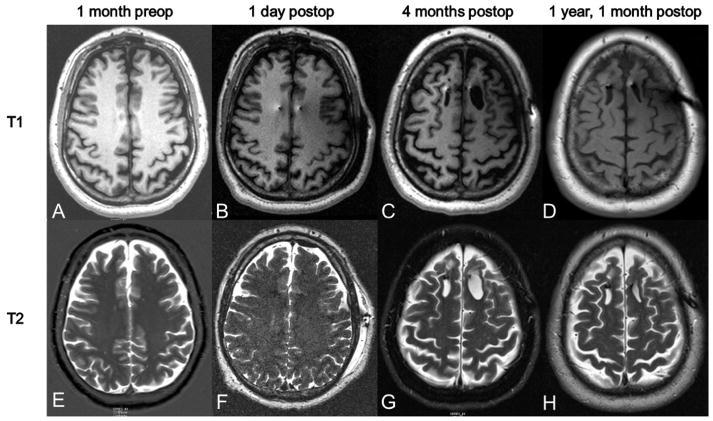

A 48-year-old right-handed man presented with a nine-year history of declining memory and organizational skills that were noticed by the patient, his family, and work associates. MRI demonstrated mild global cerebral volume loss (Figure 1A). The patient was followed at the Johns Hopkins University (JHU) Memory and Alzheimer’s Treatment Center as part of the ADvance multicenter Alzheimers Disease DBS trial as a candidate for bilateral DBS-f. This one-year, delayed-start, double-blind randomized trial is a feasibility study designed to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of DBS-f (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01608061; NIH R01-AG042165).

FIG. 1.

T1 and T2 post imaging sequences. Imaging was obtained 1 month preoperatively and then at several time points postoperatively. Postoperative time points included 1 day, 4 months, and 1 year, 1 month. No edema or abnormalities are seen on the 1 day postop scans. The cystic lesion was first noted on the 4 month postop scan and is visible in both T1 and T2 sequences. The lesion is noted to be stable at 1 year and 1 month postoperatively, with slight involution of the left frontal lesion.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient overseen by a JHU Institutional Review Board. Bilateral DBS-f lead placement was performed in May 2013. A Leksell stereotactic base ring was placed on the patient and MR imaging was performed for targeting. MR imaging was stable with respect to imaging one month prior. The target was located 2 mm anterior and parallel to the vertical portion of the fornix within the hypothalamus, the most ventral contacts were 2 mm above the optic tract dorsal surface, and approximately 5 mm lateral to the midline bilaterally2. Left and right burr holes were drilled according to the planning station derived coordinate, and arc and ring settings. The final trajectories and lead placements were accepted after autonomic effects (including blood pressure elevation and a sensation of warmth) could be demonstrated beginning at approximately 5–7 V of stimulation.

PET and noncontrast CT immediately postoperatively demonstrated no evidence of acute territorial infarct, focal mass lesion, or midline shift and confirmed bilateral forniceal electrode placement. MRI one day postoperatively also confirmed placement (Figure 1B). Of note, the T2 sequences revealed no hyperintensities or edema along the lead tracts (Figure 1F). The specific absorption rate (SARS) values used for the postoperative MRI are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

SAR Values of Postoperative MRI*

| Series # | Sequence | SAR value (W/kg) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scout | 0.02 |

| 2 | T1 3DMPRAGE | 0.02 |

| 3 | T1 3DMPRAGE | 0.02 |

| 4 | T2 Axial tse | 0.28* |

| 5 | T2 Axial tse_384 | 0.26* |

| 6 | T2 Coronal 3D tse | 0.1 |

Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) values for the patient’s postoperative day 1 MRI scan.

SAR values that exceed 0.1 W/kg recommended limit

The later postoperative course was uncomplicated with follow up visits one and three months after surgery. Interval CT/PET imaging performed one month post implantation demonstrated focal relative decreased FDG uptake identified at the right frontal vertex in a region demonstrating ill-defined hypoattenuation on noncontrast CT images in the area traversed by the right-sided electrode, possibly representing vasogenic edema.

Three months postoperatively, the subject and caregiver reported worsening in cognition accompanied by anxiety and a complaint that his “left side of brain is asleep.” The subject was evaluated in clinic and the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Score-Cognitive 11 Subscale (ADAS-Cog11) score increased (worsened) to 22 from a baseline of 19 but the psychiatric and neurological exams were unremarkable. MRI demonstrated interval development of cystic encephalomalacia within the frontal lobes just posterior to the deep brain leads, left greater than right (Figure 1C). The left cystic region measured 2.56 cm in the A-P axis by 1.5 cm wide at its maximum extent and the right cystic region measured 2.12 cm in the A-P axis by 1.22 cm wide at its maximum extent with a depth of 3.6 cm. No clinical intervention was taken at this time and the event was reported as an adverse event.

The encephalomalacic cavity was evident on further imaging six months postoperatively, however, the cavity on the left had decreased in width by nearly one half, while the cavity on the right remained unchanged. An MRV at that time demonstrated a patent sagittal sinus. The patient underwent MRI with and without contrast one year and one month postoperatively. This demonstrated unchanged position of the DBS leads 4mm anterior to the fornices with lead tips in the hypothalamus bilaterally. Stable findings of minimal encephalomalacia at the point of entry of the leads into the superior frontal sulci bilaterally were also noted (Figure 1D). SWI sequence imaging at this time also demonstrated no marked areas of hypointensity, indicating no evidence of hemorrhage along the stimulating lead tracks.

Discussion

Deep brain stimulation of the fornix may provide a new avenue for improving the symptoms of AD, a goal that has so far eluded the scientific community. The impetus for DBS-f came from a case report demonstrating induced enhancement of memory in a patient implanted in the hypothalamus near the fornix for treatment of his obesity1. An open-label pilot study of DBS in AD demonstrated possible slowing of cognitive decline and improvement in glucose utilization.2,3 Additionally there is evidence the structural integrity of the fornix predicts cognitive and functional decline in prodromal AD4. These efforts led to a larger randomized clinical trial, the ADvance Study, to assess the efficacy of DBS-f for the treatment of AD. This report details an adverse event wherein one patient demonstrated bilateral encephalomalacia at the cortical entry site of the DBS leads on delayed postoperative imaging while, to date, remaining clinically asymptomatic.

Encephalomalacia is a known, but relatively rare, post-surgical complication of DBS lead implantation5,6. Retrospective studies have estimated the incidence of encephalomalacia at around 4.2%6. Instances of encephalomalacia are usually unilateral as opposed to the bilateral nature of the event here. In these cases, encephalomalacia was not evident immediately postoperatively but on scans an average of 19 months postop. In most of these cases, immediate MR imaging had shown intraparenchymal hemorrhage or edema6. The ADvance trial includes 42 participants implanted bilaterally yielding 84 DBS-f implantation sites. To date, no other patient implanted with DBS-f for AD has demonstrated encephalomalacia on postoperative imaging, including six patients implanted for a phase I clinical trial focused on safety. Including our patient, the incidence of encephalomalacia in DBS-f is 2.1% per side (2/96). While this rate is lower than that reported with DBS for PD, it is too early in the implementation of DBS-f, with too few patients implanted, to provide conclusive rates.

Beyond standard operative risk, other potential mechanisms for encephalomalacia in this case include side effects of MRI and vascular complications. A large number of clinical series and animal in vivo testing has demonstrated the safety of MRI postoperatively in patients implanted with DBS6,7. These studies have focused on several specific features of the MRI process including the specific absorption rate (SAR) value, the DBS configuration, Tesla strength of the MRI, the RF coils, and the gradient. These reviews, and Medtronic’s own recommendations, limit the average SAR to 0.1 W/kg. Of note, there have been two case reports demonstrating neurological sequelae post-imaging, including hemorrhage, aphasia, and dystonia. In the case of hemorrhage leading to aphasia, the local SAR values ranged from 0.57 to 1.26 with local SAR values up to 3.92 W/kg7.

In the current patient, the immediate postoperative imaging exceeded this average SAR value for two sequences (Table 1). The SAR values for these two sequences (0.28 and 0.26 W/kg) were still below the original upper limit of 0.4 W/kg set by the lead manufacturer. Some research groups have shown safety of scanning with SAR values in excess of 0.1W/kg. SAR values up to 0.8 W/kg have been used in 96 patients in 192 MRIs without adverse effects6.

Early postoperative imaging showed no evidence of acute territorial infarct (Figure 1B). Susceptibility weighted imaging scans 1 year out demonstrated no hypodensities, reinforcing the lack of evidence for tract hemorrhage. A review of the imaging findings by neurosurgeons at the clinical site and at other sites in the trial suggested (but not unanimously) the encephalomalacia may have been caused by a stroke secondary to venous thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus initiated during the DBS lead implantations, but other neurosurgeons in the trial did not agree on this interpretation.

Venous thrombosis leading to infarction and delayed neurological decline is a rare (<1/100 patients), but serious adverse event of DBS implantation8–10. Although an MRV demonstrated a patent superior sagittal sinus 6 months postoperatively, this was two months after the patient’s clinical symptoms and the venous stasis may have resolved by that point and therefore no conclusive imaging of venous infarction were obtained. Imaging in favor of venous infarction includes CT imaging done one month postoperatively that demonstrated an area of possible vasogenic edema in the right frontal region as well as the bilateral nature and location of the lesions near the midline sagittal sinus.

Conclusion

We report bilateral encephalomalacia in a patient implanted with DBS-f for AD. A venous infarct either in the superior sagittal sinus or bilateral cortical venous structures most likely caused this. However, other factors may have contributed such as an elevated SAR during MRI imaging. DBS-f is being studied for use in AD with potential wide scale implementation impacting thousands of patients. Therefore, further study is warranted into this and other possible adverse effects of DBS-f in patients with AD.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: NIH R01 – 1R01AG042165-01A1, Functional Neuromodulation Ltd

Footnotes

Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB #: NA_00072467

References

- 1.Hamani C, McAndrews MP, Cohn M, et al. Memory enhancement induced by hypothalamic/fornix deep brain stimulation. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(1):119–123. doi: 10.1002/ana.21295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laxton AW, Tang-Wai DF, McAndrews MP, et al. A phase I trial of deep brain stimulation of memory circuits in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):521–534. doi: 10.1002/ana.22089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith GS, Laxton AW, Tang-Wai DF, et al. Increased cerebral metabolism after 1 year of deep brain stimulation in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(9):1141–1148. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mielke MM, Kozauer NA, Chan KCG, et al. Regionally-specific diffusion tensor imaging in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. NeuroImage. 2009;46(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martínez JAE, Pinsker MO, Arango GJ, et al. Neurosurgical treatment for dystonia: Long-term outcome in a case series of 80 patients. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2014;123:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chhabra V, Sung E, Mewes K, Bakay RAE, Abosch A, Gross RE. Safety of magnetic resonance imaging of deep brain stimulator systems: a serial imaging and clinical retrospective study. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2009;112(3):497–502. doi: 10.3171/2009.7.JNS09572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson JM, Tkach J, Phillips M, Baker K, Shellock FG, Rezai AR. Permanent Neurological Deficit Related to Magnetic Resonance Imaging in a Patient with Implanted Deep Brain Stimulation Electrodes for Parkinson’s Disease: Case Report. Neurosurgery November 2005. 2005;57(5) doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000180810.16964.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamani CMD, Richter E, Schwalb JM, Lozano AMMD. Bilateral Subthalamic Nucleus Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review of the Clinical Literature. Neurosurgery. 2005 Jun;56(6):1313–1324. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000159714.28232.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morishita T, Okun MS, Burdick A, Jacobson CE, Foote KD. Cerebral Venous Infarction: A Potentially Avoidable Complication of Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface. 2013;16(5):407–413. doi: 10.1111/ner.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umemura A, Jaggi JL, Hurtig HI, et al. Deep brain stimulation for movement disorders: morbidity and mortality in 109 patients. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2003;98(4):779–784. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.4.0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]