Abstract

Effective communication with patients and their caregivers continues to form the basis of a constructive clinician-patient relationship and is critical to providing patient-centered care. Engaging patients in meaningful, empathic communication not only fulfills an ethical imperative for our work as clinicians, but also leads to increased patient satisfaction with their own care and improved clinical outcomes. While these same imperatives and benefits exist for discussing goals of care and end-of-life, communicating with patients about these topics can be particularly daunting. While clinicians receive extensive training on how to identify and treat illness, communication techniques, especially those centering around emotion-laden topics such as end-of-life care, receive short shrift medical education. Fortunately, communication techniques can be taught and learned through deliberate practice and in this article we seek to discuss a framework, drawn from published literature and our own experience, for approaching goals of care discussions in patients with cardiovascular disease.

Medical advances now allow our patients to survive severe cardiovascular illness and live well into old age. Patients that would have previously died following acute myocardial infarction or with the development of advanced circulatory dysfunction are now able to live longer and often better due to technological and therapeutic innovations. However, along with these improvements comes an increasing number of patients presenting to our clinics and hospitals plagued with multiple comorbid conditions who are living and dying in a number of different care settings. Accepting mortality in the wake of these modern medical interventions has become more difficult, as it can be challenging for patients and their loved ones to understand that there are limits to our ability to prolong life. As such, patient-clinician discussions of decompensation, death and how to plan for these inevitable outcomes are often delayed and avoided until an acute event occurs or death is imminent. For example, only 25% of patients with severe heart failure enrolled in the landmark SUPPORT (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments) trial reported having end-of-life (EOL) discussions with their physicians1.

The avoidance of this topic is evident by the lack of advance care planning in most patients with chronic cardiovascular disease. Less than half of patients with a serious cardiovascular illness have completed an advance directive2–4. Even when completed, most fail to address wishes for life-prolonging treatments such as resuscitation, dialysis, and artificial nutrition2, 4. A lack of goals of care discussion and EOL planning may contribute to a delay in decision-making until patients are hospitalized in close proximity to death. In a community population of patients with heart failure, one-quarter of decedents changed their resuscitation preference from Full Code to Do Not Resuscitate while hospitalized in the final week of life5. Hospice is utilized in less than half of elderly patients with heart failure prior to death6, and patients are often repeatedly hospitalized at the EOL despite the fact that most patients say they would want to avoid hospitalization at death7.

In addition to the negative impact on quality of life and bereavement for patients and caregivers, the financial burden to families and society that EOL care imposes can be profound. One out of every four Medicare dollars is spent on care in the last six months of life and despite reductions in total days spent in a hospital, patients are spending more time in an intensive care unit at the EOL now than ever before8. Ultimately, for true individualized care that achieves healthcare value, our goal is to align a patient’s care with their goals, preferences and values.

To accomplish such an alignment, clinicians must be able to elicit and understand these goals, integrate them into the current medical context and recommend the course of action that best aligns with those goals and wishes. This is not a one-time discussion but an iterative process whereby a clinician identifies a patient’s understanding of their medical issues, provides them with a framework to assess their goals and allows them time to reflect and discuss with family and caregivers. This process allows patients to change their goals and values over time as their health status changes but always requires clinician guidance and recommendations about how a plan of care helps or does not help a patient achieve those goals. These clinician-patient conversations go by many different names in the literature. For the purposes of this manuscript, we will refer to them as goals of care discussions.

ACKNOWLEDGING AND OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO GOALS OF CARE DISCUSSIONS

Numerous data exists to support the benefits of discussing EOL wishes with patients, including strengthening the clinician-patient relationship9, improved quality of life at the EOL, and reducing caregiver burden10. However, clinicians often acknowledge barriers to having these discussions11, which are each addressed below.

Patient Factors

In one survey of clinicians who care for patients with heart failure, the most frequently cited reason for avoiding goals of care discussions was that the clinician sensed that the patient or family were not ready to talk11. While this may be true, it can be difficult to gauge without broaching the conversation. In fact, most patients and caregivers are willing to discuss their goals and wishes for care at the EOL, and rely on their physician to initiate the discussion. Approaching these discussions as a part of the routine care of the patient can help in normalizing the process12.

Family/Caregiver Factors

Families and caregivers often play a prominent role in the decision-making process, particularly when patients are seriously ill or unable to make their own decisions. A recent study found that family members’ difficulty accepting a loved ones’ poor prognosis and understanding limitations and complications of life-sustaining treatment were the two most important barriers to goals of care discussions identified by physicians and nurses caring for seriously ill hospitalized patients13. Families are frequently emotionally overwhelmed and effective communication skills are needed to guide these conversations, interpret previously discussed patient wishes and relay prognostic information in a way that informs the discussion. In addition, including family and other caregivers in goals of care discussions prior to the time when they are asked to be a surrogate decision-maker can help them to understand their loved ones’ preferences for care.

Fear of Destroying Hope

Clinicians are often concerned that discussing wishes surrounding EOL care may lead to a reduction or loss of patient hope. Contrary to this widespread myth is the fact that empathic discussions about prognosis and EOL care can build trust without negatively impacting hope14–17. Patients who discuss their EOL wishes with their physician have less fear and anxiety, believe that their physicians better understand their preferences, and feel a greater ability to influence their own care15–17.

Difficult Prognostication

Linked to the concern about destroying hope is the difficulty of relaying and responding to questions about prognosis. An assessment of prognosis is an important part of a discussion around EOL wishes, as patients with limited prognosis may make different choices18. It can be challenging to provide an accurate estimate of prognosis, particularly in patients with organ failure such as heart failure, which often follows a fluctuating pattern of decline19, but can vary substantially in an individual patient, with the picture further complicated by the possibility of unexpected sudden death. Furthermore, both patients and clinicians tend to overestimate life expectancy20, 21. Fortunately, numerous tools exist to aid in estimating patient survival. Perhaps the most widely used in patients with heart failure is the Seattle Heart Failure model22, which is available via an online calculator (https://depts.washington.edu/shfm/app.php) and provides an estimate of life expectancy that can be useful in clinical practice. There are also several clinical indicators of adverse prognosis which can be universally helpful across disease states including repeated hospitalizations, unintended weight loss of 10% or more of body weight, and progressive functional decline. It can also be informative for experienced clinicians to ask themselves “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?”23, 24 An affirmative answer identifies patients at high risk for mortality.

Lack of Time

It can be difficult in the midst of a busy clinical schedule to make time to discuss goals of care. However, these conversations may save time later. As noted in a recent scientific statement from the American Heart Association on decision making in heart failure12, “Difficult discussions now will simplify difficult decisions in the future.” The time spent is not as long as you might imagine. On average experts spend 14.8 minutes per goals of care discussion, which is longer than more novice physicians at only 8.1 minutes, as experts tend to spend more time discussing psychosocial and quality of life preferences25. Because EOL preferences and planning are an iterative process that involves serial discussions, having the conversation earlier may normalize and familiarize the patient and family with the process, thus easing discussions later.

Lack of Confidence and Clinician Discomfort

Many physicians feel uncomfortable initiating the discussion11, in part because they may feel ill-equipped with the tools necessary to help guide the conversation. In one multi-center survey, 30% of clinicians reported a low level of confidence in either discussing or providing EOL care for their patients with heart failure11. Beyond the aforementioned reasons, clinicians are often uncomfortable with patient expressions of emotion. Emotional responses are normal in the course of a serious illness and can provide clues to patient understanding of their illness and their current level of coping. Physician difficulty with responding to emotion is in part due to a lack of training in how to respond, but also reflects a desire to “fix” these emotions. The ability to respond to emotion can align clinicians with their patients and strengthen patient-provider bonds.

HOW-TO APPROACH GOALS OF CARE DISCUSSIONS

Timing of Goals of Care Discussions

Many physicians prefer to wait until patients with life-threatening illness exhaust traditional therapeutic options before discussing EOL care26. While an acute event or a change in health status is an important time to discuss goals of care, it is a much better time to revisit and confirm goals and preferences rather than broaching the subject for the first time. While there are numerous “triggers” for reviewing and updating goals of care (Box 1), we would also advocate that the discussion occurs annually as a part of the routine care of the patient12. This “annual review” approach has been suggested in the care of patients with heart failure, but could be utilized in all patients with chronic cardiovascular disease. Discussing a patient’s goals and values for their healthcare outside of a medical crisis allows time to identify patient understanding of their illness and place this within the medical context, a process that allows clinicians to provide recommendations and respond to questions and emotions in a non-emergent setting.

Box 1. Triggers for Reviewing Goals of Care.

| • Annual visit | • Disease worsening/ progression |

| • Repeated or severe hospitalization(s) | • Considering major procedures or interventions |

| • Change in functional or health status | • Change in social support system, death of a spouse |

| • Change in living situation (independent to assisted or long-term care facility) | • Clinician response of “no” to “Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next year?” |

Components of Goals of Care Discussions

While the specific content covered during goals of care discussions may change depending on the circumstance (annual visit, acute hospitalization, considering major intervention), the approach can be similar. As clinicians, we have a tendency to focus solely on obtaining preferences for decisions about specific interventions (such as resuscitation) and procedures. However, it is important to use these conversations as an opportunity to understand the patient’s goals, preferences and values so that you can help to guide them on how decisions for specific interventions will or will not align with these expressed goals. If you are approaching the conversation as a part of the routine care of the patient, it can be helpful to open up with a normative statement such as “I like to talk to all of my patients about some topics that can be hard to discuss. That includes talking to people about what is most important to them and what they would want if their health worsened.” Key components of goals of care discussions are shown in Box 227, 28.

Box 2. Key Elements of Goals of Care Discussions.

| • Review previous discussions and documented wishes for care | “What conversations have you had with other doctors and your family about the care you would want to receive |

| • Assess the patient’s willingness to receive information and their preferred role in decision making | “How much do you want to know about your condition?” “Do you make your own decisions about your care, or do you prefer someone else makes those decisions?” |

| • Discuss prognosis and anticipated outcomes for current treatment. Assess for patient understanding | “In order to plan for the future, I think it is important to discuss what the expected course of your [condition] may be.” |

| • Ask the patient about their values, goals, and fears for the future | “What makes life worth living for you?” “Given the severity of your illness, what is most important for you to achieve?” “What are your biggest worries as we discuss these issues?” |

| • Discuss health states the patient would find unacceptable | “Would there be any circumstances under which life would not be worth living?” |

| • Discuss specific preferences for life-sustaining treatments and interventions being considered | “Have you thought about what treatments you would want and not want if your health got worse?” |

| • Summarize and make a plan | |

| • Complete/ update advance directives and document conversation in medical record |

The first step is to review previous discussions and patient-documented preferences. If this is the first time that you are talking with the patient about their goals of care, it is helpful to assess what conversations they have had with previous clinicians and any electronic documentation of preferences or discussions. It is also important to invite patients to participate in the discussion and ascertain whether there are other individuals who help them to make decisions that it would be important to include. If patients do not want to engage in the discussion, it is helpful to explore the reasons why not.

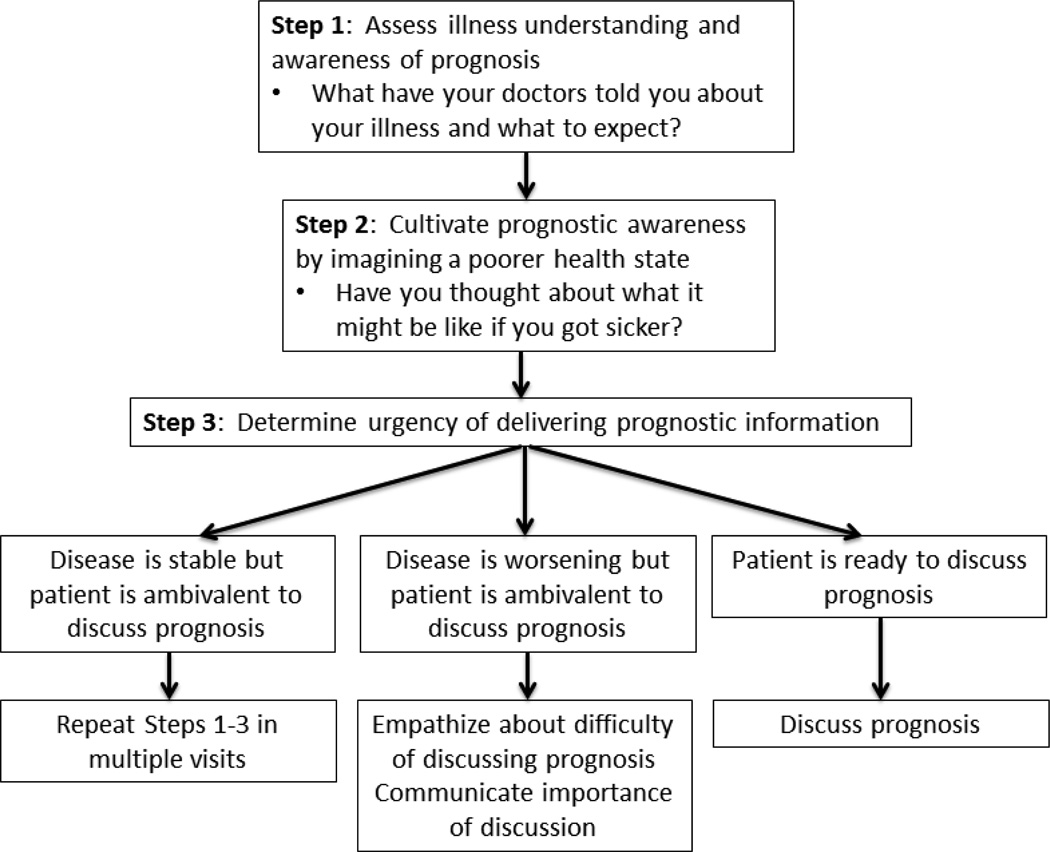

A critical next step is to assess patient understanding of their underlying cardiovascular illness (Figure 129). A patient with a widely inaccurate assessment of their underlying illness will require a different approach than a patient who understands their medical situation and is ready to talk about next steps. Part of this approach requires that a patient be ready to hear and discuss their prognosis and success often relies on whether they can integrate the information into their goals and values for care. For patients that lack understanding of their illness and its prognosis and who are not ready to hear more information about this, multiple conversations may be required. It can be helpful to acknowledge how difficult it can be to discuss prognosis with a statement such as: “It can be difficult to talk about the fact that you might get sicker or die from your heart failure” while also underscoring the importance of the discussion. Additional assistance from palliative care colleagues who specialize in complex communication interactions may also be beneficial.

Figure 1. Cultivating Prognostic Awareness.

Adapted with permission from Jackson et al29

Even with permission, discussing prognosis can be the most challenging part of the conversation. However, we must underscore its importance in ensuring that the patient, family, and healthcare team are all on the same page, particularly when a patient has limited life expectancy. When delivering prognostic information, it is important to include ranges (e.g. days to weeks, months to years) and acknowledge uncertainty. While we do our best to estimate prognosis, uncertainty still exists and can make patients and families uncomfortable. Smith et al recently suggested three tasks that clinicians can perform to alleviate anxiety and help to normalize uncertainty for patients and families30:

Normalize the uncertainty of prognosis- “While no one can tell you for certain how long you have left to live, I am concerned…”

Acknowledge and address emotions about uncertainty- use of NURSE statements (Box 3)

Help manage the impact that uncertainty of prognosis may have in daily life-“How can I help you to cope with uncertainty?”

Box 3. SPIKES Framework for Approaching Difficult Conversations with Patients.

| Scene |

|

| Perception |

|

| Invitation |

|

| Knowledge |

|

| Empathy |

|

| Summary |

|

The bulk of the discussion may be spent understanding the patient’s values, goals and fears. Values form the basis for how you approach the world and your healthcare decisions, whereas goals are targets to try and reach. For example, patients may value their independence, and have a goal of remaining in their own home until death. Some common goals and values expressed by patients include preserving quality of life, remaining independent, being free from pain and other forms of suffering, being mentally alert/competent, and living long enough to accomplish a specific milestone or attend a cherished family event. It is important to recognize that not all goals may be attainable for an individual, but having an understanding of a patient’s goals can be helpful to you in guiding them to make decisions that best align with those goals. Similarly, understanding a patient’s fears about the future can be important in understanding why they may make certain decisions. Sometimes fears are based on a misunderstanding or misconception that can be addressed and resolved. For example, some patients may fear being shocked from their internal cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) near death, as most patients don’t realize the ICD can be deactivated without being explanted31. Discussion of this fear could prompt education about device deactivation, and alleviation of fear. Furthermore, acknowledging and discussing fears can provide patients validation and comfort.

Before discussing specific preferences for therapy, it can be beneficial to simply ask patients about what health states they would find unacceptable. If a patient says they would not want to be “kept alive with machines” for any period of time, you can guide them in making decisions about things such as preferences for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and mechanical ventilation that are in alignment with that preference. This discussion may lay the groundwork for other decisions that could lead to unacceptable health states for a patient. Similarly, it may provide information to craft decisions on time-limited trials of some therapies (e.g. high risk surgery or hemodialysis) as long as they help a patient to achieve a goal and do not cause unacceptable side effects or outcomes.

In recent years, there has been a heightened understanding of the importance of shared decision making, and of ensuring that patients are fully informed of the risks and benefits of alternative treatment options. Several tools to help guide physicians and patients through the decision-making process have been or are being developed to aid in decisions such as whether to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention, proceed with implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation as primary prevention, or have a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) as destination therapy. Which decisions need to be discussed should be tailored to the individual patient—not all decisions need to be discussed in every patient.

Goals of care discussions in the setting of worsening health status often follow a format of breaking bad news, such as a poor prognosis, followed by the need to respond to a new emotion. The SPIKES mnemonic (Box 3) was conceived by Dr. Robert Buckman as a structured framework to aid clinicians in breaking bad news32, and can be helpful in framing responses in goals of care discussions. A more abbreviated version of this framework is the Ask-Tell-Ask structure. Ask-Tell Ask entails asking the patient his/her understanding of the problem, telling the patient his/her test results, diagnosis, prognosis, or other news, and then asking the patient about his/her understanding and feelings.

Regardless of the approach taken in goals of care discussions, when developing a plan moving forward, it is important to avoid language that creates two tiers of care (Box 4). This includes referring to cure or disease-targeted therapies as “aggressive” or asking patients if they want clinicians to keep doing “everything possible”. It is important to recognize that choosing to focus on comfort does not mean that a patient is “giving up” and that clinicians can work just as hard to focus on meeting the patient’s goal of comfort as they did in providing life-sustaining therapies.

Box 4. Dos and Don’ts of Goals of Care Discussions.

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| • Listen and let the patient do most of the talking | • Wait until death is imminent |

| • Break information into small chunks | • Qualify treatment as |

| • Check frequently for understanding | • Ask patients if they want |

| • Provide empathy and support | • Tell patients there is |

| • Emphasize what can be done | • Focus solely on preferences for procedures |

| • Offer your recommendation(s) based on their goals and values | • Exclude surrogate decision-makers from the discussion |

At the end of the discussion, it is helpful to summarize and develop a plan. The plan can involve numerous possibilities such as identifying a surrogate decision-maker, discussing wishes with family, moving forward with a procedure, starting a medication to help with symptoms, or enrolling in hospice. Patients and families often fear abandonment when transitioning to a comfort-directed approach to care at the EOL33, and a plan for continuity and addressing symptoms may help to alleviate those concerns.

Finally, both providers and patients need to document these discussions and their results. For patients, this often requires completing an advance directive. The two most common types of advance directives are the durable power of attorney for health care and living will. The goal of a durable power of attorney for health care is to authorize another person (health care proxy) to make decisions for the patient if they are unable. It is important to encourage the patient to talk with the proxy about their goals, values and preferences, and to ensure they are comfortable in assuming the role of a surrogate decisionmaker. A living will outlines the kinds of treatment and care a patient wants at the EOL. Advance directives differ in their composition, but often allow patients to document their values, goals, and fears in more general terms. Specific preferences for life-sustaining treatments (cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation artificial nutrition), pain control, location of death, and organ donation are also often included. While usually overlooked34, 35, preferences for management of existing life-sustaining cardiac devices such as ICDs and LVADs at the EOL should also be addressed.

Role of Palliative Care Specialists

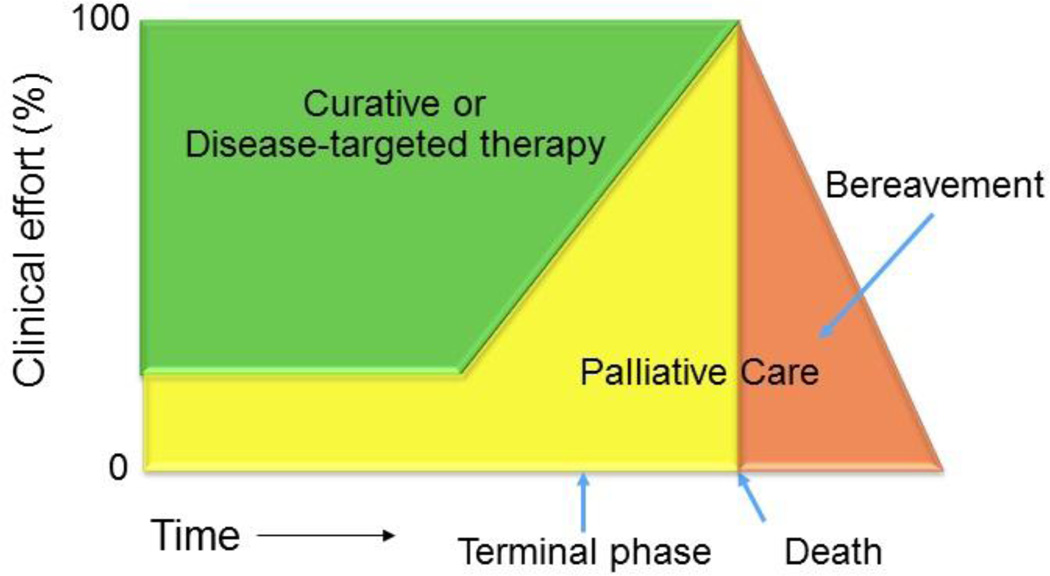

Palliative care specialists have extensive training and experience in having goals of care discussions, and can be exceptionally helpful in navigating complex conversations with patients and families. Palliative care specialists are uniquely positioned to work with cardiology clinicians in the care of patients with serious illness by providing guidance in the management of complex symptoms, offering psychosocial support for patients and families, and assisting in communication when decision-making is complex or fraught with conflict. Palliative care services are appropriate at any stage of a serious illness and can be utilized while patients are receiving disease-directed therapies, such as inotropes or LVAD in heart failure or transcutaneous aortic valve replacement in aortic stenosis. It is often natural for a patient’s care to transition from focusing primarily on disease-targeted or curative therapy to palliation of symptoms as their illness progresses or health status worsens (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Emerging Model of Palliative Care.

Based upon American Medical Association Institute for Medical Ethics (1999): EPEC: Education for physicians on end-of-life care (Robert Wood Johnson)40

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Cultural Differences

The clinician should be aware that cultural beliefs may impact patient wishes for knowledge about prognosis as well as their values, goals, and preferences for treatment. While a true cultural competence is not feasible, a sense of cultural curiosity can be cultivated in all clinicians. Asking: “Tell me how your religious and/or cultural beliefs affect how you wish to talk about your healthcare”, can provide valuable information to allow clinicians to engage in these discussion without making assumptions based on stereotypes.

Patient Lacks Decision-Making Capacity

Decision-making capacity involves determining whether a patient is psychologically capable of making medical decisions. If a patient lacks decision-making capacity, they cannot provide informed consent for medical interventions or procedures, and we rely on advance directives and surrogate decision-making. The hierarchy for surrogate decision-making varies by state, so it is important to be aware of the laws in the state where you practice. When working with a surrogate decision-maker, it is helpful to first review preferences outlined in advance directives to guide decision-making. Second, clinicians can help family members use substituted judgment to try and make the decision that the patient would have made if they were able (i.e. “If your mother could wake up and understand her condition and then return to it, what would she tell you to do?”). While substituted judgment is not always accurate36, it can help to alleviate some of the burden by framing the decision as the patient’s choice rather than the surrogate’s37.

Cardiac Devices at the End-of-Life

The number of patients with implanted cardiac devices such as ICDs and LVADs are increasing. Most clinicians regard such devices as life-sustaining, and a patient’s wishes for continuation of such life-sustaining treatments may change as their health status changes and they approach the EOL. Patients (or surrogate decision-makers in the event that a patient lacks decision-making capacity) have the ethical right to request withdrawal of such life-sustaining therapies. However, most patients have not discussed device deactivation with their physicians and many are not aware that deactivation is an option. Societies have recommended physicians discuss device deactivation with their patients38, and this would preferably be done in an iterative fashion as a part of the annual goals of care discussion. During these conversations, it is important to gauge what the patient/ family understand about their illness and the role of the device, define their goals of care, and tailor recommendations about whether to deactivate the device based upon these goals. Gafford and colleagues have outlined a process for deactivating LVADs at the EOL39 which underscores the need for multidisciplinary coordination to minimize patient discomfort.

CONCLUSION

It is crucial for clinicians to feel comfortable approaching goals of care discussions with patients, as these conversations are essential to aligning care delivery with patient preferences. We hope that use of this framework will enable clinicians to feel empowered to discuss goals of care with their patients.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krumholz HM, Phillips RS, Hamel MB, Teno JM, Bellamy P, Broste SK, et al. Resuscitation preferences among patients with severe congestive heart failure: Results from the support project. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. Circulation. 1998;98:648–655. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.7.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlay SM, Swetz KM, Mueller PS, Roger VL. Advance directives in community patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:283–289. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkpatrick JN, Guger CJ, Arnsdorf MF, Fedson SE. Advance directives in the cardiac care unit. Am Heart J. 2007;154:477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nkomo VT, Suri RM, Pislaru SV, Greason KL, Mathew V, Rihal CS, et al. Advance directives of patients with high-risk or inoperable aortic stenosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1516–1518. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunlay SM, Swetz KM, Redfield MM, Mueller PS, Roger VL. Resuscitation preferences in community patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:353–359. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, Whellan DJ, Kaul P, Schulman KA, Peterson ED, Curtis LH. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:196–203. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher ES, Bronner KK. End of life care: A report from the dartmouth atlas of health care. [Accessed January 10, 2015];2007 http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/keyissues/issue.aspx?con=2944. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goodman DC, Esty AR, Fisher ES, Chang C. Trends and variations in end-of-life care for medicare beneficiaries with severe chronic illness. [Accessed February 23, 2015];A report of the dartmouth atlas project. 2011 http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/reports/EOL_Trend_Report_0411.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weng HC, Steed JF, Yu SW, Liu YT, Hsu CC, Yu TJ, et al. The effect of surgeon empathy and emotional intelligence on patient satisfaction. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16:591–600. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunlay SM, Foxen JL, Cole T, Feely MA, Loth AR, Strand JJ, et al. A survey of clinician attitudes and self-reported practices regarding end-of-life care in heart failure. Palliat Med. 2015;29(3):260–267. doi: 10.1177/0269216314556565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, Goldstein NE, Matlock DD, Arnold RM, et al. Decision making in advanced heart failure: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2012;125:1928–1952. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824f2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, Lamontagne F, Ma IW, Jayaraman D, et al. Barriers to goals of care discussions with seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families: A multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7732. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Retrum JH, Allen LA, Shakar S, Hutt E, et al. Giving voice to patients' and family caregivers' needs in chronic heart failure: Implications for palliative care programs. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1317–1324. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary J. Prognosis communication in serious illness: Perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1398–1403. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meredith C, Symonds P, Webster L, Lamont D, Pyper E, Gillis CR, Fallowfield L. Information needs of cancer patients in west scotland: Cross sectional survey of patients' views. BMJ. 1996;313:724–726. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Gramelspacher GP, Perkins AJ, Zhou XH, Wolinsky FD. The effect of discussions about advance directives on patients' satisfaction with primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00215.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fried TR, Van Ness PH, Byers AL, Towle VR, O'Leary JR, Dubin JA. Changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among older persons with advanced illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:495–501. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0104-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289:2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allen LA, Yager JE, Funk MJ, Levy WC, Tulsky JA, Bowers MT, et al. Discordance between patient-predicted and model-predicted life expectancy among ambulatory patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2008;299:2533–2542. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.21.2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320:469–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy WC, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Sutradhar SC, Anker SD, Cropp AB, et al. The seattle heart failure model: Prediction of survival in heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1424–1433. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.584102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, Gansor J, Senft S, Weaner B, et al. Utility of the "surprise" question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1379–1384. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00940208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, Auber M, Kurian S, Rogers J, et al. Prognostic significance of the "surprise" question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:837–840. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roter DL, Larson S, Fischer GS, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA. Experts practice what they preach: A descriptive study of best and normative practices in end-of-life discussions. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3477–3485. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, Jr, Baum SK, Virnig BA, Huskamp HA, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer. 2010;116:998–1006. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You JJ, Dodek P, Lamontagne F, Downar J, Sinuff T, Jiang X, et al. What really matters in end-of-life discussions? Perspectives of patients in hospital with serious illness and their families. CMAJ. 2014;186:E679–E687. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.140673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, Pirl WF, Temel JS, Back AL. The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: A communication guide. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:894–900. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith AK, White DB, Arnold RM. Uncertainty--the other side of prognosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2448–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1303295. Raphael CE, Koa-Wing M, Stain N, Wright I, Francis DP, Kanagaratnam P. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipient attitudes towards device deactivation: How much do patients want to know? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34:1628–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raphael CE, Koa-Wing M, Stain N, Wright I, Francis DP, Kanagaratnam P. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipient attitudes towards device deactivation: How much do patients want to know? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2011;34:1628–1633. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buckman R. How to break bad news: A guide for healthcare professionals. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Back AL, Young JP, McCown E, Engelberg RA, Vig EK, Reinke LF, et al. Abandonment at the end of life from patient, caregiver, nurse, and physician perspectives: Loss of continuity and lack of closure. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:474–479. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swetz KM, Mueller PS, Ottenberg AL, Dib C, Freeman MR, Sulmasy DP. The use of advance directives among patients with left ventricular assist devices. Hosp Pract (1995) 2011;39:78–84. doi: 10.3810/hp.2011.02.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tajouri TH, Ottenberg AL, Hayes DL, Mueller PS. The use of advance directives among patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:567–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sulmasy DP, Terry PB, Weisman CS, Miller DJ, Stallings RY, Vettese MA, et al. The accuracy of substituted judgments in patients with terminal diagnoses. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:621–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torke AM, Alexander GC, Lantos J. Substituted judgment: The limitations of autonomy in surrogate decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1514. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0688-8. 151738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lampert R, Hayes DL, Annas GJ, Farley MA, Goldstein NE, Hamilton RM, Kay GN, Kramer DB, Mueller PS, Padeletti L, Pozuelo L, Schoenfeld MH, Vardas PE, Wiegand DL, Zellner R. Hrs expert consensus statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (cieds) in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:1008–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gafford EF, Luckhardt AJ, Swetz KM. Deactivation of a left ventricular assist device at the end of life #269. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:980–982. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.9490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Medical Association Institute for Medical Ethics (1999): EPEC: Education for physicians on end-of-life care (Robert Wood Johnson).