Abstract

Stem cell-based tissue regeneration offers potential for treatment of craniofacial bone defects. The dental follicle (DF), a loose connective tissue surrounding unerupted tooth, has been shown to contain progenitor/stem cells. Dental follicle stem cells (DFSCs) possess strong osteogenesis capability, which makes them suitable for repairing skeletal defects. The objective of this study was to evaluate bone regeneration capability of DFSCs loaded into polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffold for treatment of craniofacial defects. DFSCs were isolated from the first mandibular molars of postnatal Sprague Dawley rats and seeded into PCL scaffold. Cell attachment and cell viability on the scaffold were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Alamar blue reduction assay. For in vivo transplantation, critical-size defects (CSD) were created on the skulls of 5 month-old immunocompetent rats, and the cell–scaffold constructs were transplanted into the defects. Skulls were collected at 4 and 8 weeks post-transplantation, and bone regeneration in the defects was evaluated with micro-CT and histological analysis. SEM and Alamar blue assay demonstrated attachment and proliferation of DFSCs in the PCL scaffold. Bone regeneration was observed in the defects treated with DFSC transplantation, but not in the controls without DFSC transplant. Transplanting DFSC-PCL with or without osteogenic induction prior to transplantation achieved approximately 50% bone regeneration at 8 weeks. Formation of woven bone was observed in the DFSC-PCL treatment group. Similar results were seen when osteogenic-induced DFSC-PCL was transplanted to the CSD. This study demonstrated that transplantation of DFSCs seeded into PCL scaffolds can be used to repair craniofacial defects.

Keywords: Dental follicle stem cells, Bone regeneration, craniofacial defects, Stem cell transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Various factors such as trauma, infection, tumor, and congenital deformities can cause craniofacial defects (1). Conventional approaches for treatment of craniofacial bone defects usually require the use of autograft or alloplastic materials. Both, however, have disadvantages that limit their clinical applications. For autograft, obtaining autogenous bone requires extra surgical procedures with associated co-morbidities (2, 3). Although alloplastic materials can be used for the treatment of such defects with no need of extra surgery, immune rejection and infection can occur, resulting in treatment failure. The concepts of harvesting adult stem cells (AdSCs), followed by expansion and transplantation for tissue regeneration, have been the cornerstone of the regenerative medicine. In this regard, utilization of stem cells for treatment of craniofacial defects has been attempted (4-8).

Stem cells have been isolated from various tissues, such as bone marrow, adipose tissue and skin. Invasive surgical procedures are usually needed to obtain tissues for stem cell isolation. Since impacted teeth are often extracted in dental clinics and discarded, the use of extracted teeth for stem cell isolation does not require extra surgery. Dental follicle (DF), a loose ectomesenchymal tissue surrounding unerupted teeth, has been shown to contain progenitor/stem cells. Thus, dental follicle stem cells (DFSCs) have been isolated and tested for stem cell properties (9-11). DFSCs possess strong osteogenic capability to differentiate toward the osteoblast lineage (12), which makes them suitable for repair of skeletal defects. In addition, since the DF is derived from the neural crest, the same origin of craniofacial tissues, it may be preferential to utilize DFSCs for treatment of defects in this region.

Previous studies have attempted to evaluate the hard-tissue forming potential of DFSCs in vivo. Subcutaneous transplantation of bovine and human DFSCs mixed with hydroxyapatite ceramics showed formation of mineralized structure (13, 14). Two other studies have investigated DFSCs for bone regeneration in critical-size defects created in the calvarium of immune-deficient rats. The first study demonstrated the differentiation potential of porcine DFSCs into osteogenic lineage cells (15). Similar results were observed from an independent study showing the in vivo bone formation potential of human DFSCs (16). Both studies were done by transplanting DFSC pellets without loading cells into scaffolds. However, scaffolds are important components for tissue engineering because they mimic the extracellular matrix and provide a three-dimensional structure for cell attachment and vascularization (17). In particular, scaffolds are required for regeneration of large-size defects. In the attempts to utilize AdSCs for regeneration of skeletal defects, both undifferentiated and osteo-induced stem cells have been used in separate studies, but the results were controversial (4, 5, 18). Hence, it would be necessary to compare bone regeneration capability using undifferentiated and osteo-induced stem cells under the same experimental conditions for assessment of the effectiveness of treatment protocols. In order to fill the gaps toward clinical application of DFSCs, we evaluated bone regeneration potential of DFSCs in rat calvarial critical-size defects using immunocompetent rats. Polycaprolactone (PCL) was used to make scaffolds for seeding DFSCs because studies have shown the biocompatibility of PCL to different cell types including osteoblasts, fibroblasts and stem cells in tissue regeneration (19-22). Our results from this study suggest that PCL scaffold is compatible to DFSCs for bone regeneration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Louisiana State University (LSU). Immunocompetent Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were bred to produce postnatal pups. Experiments were conducted with animals from four different litters (replicates). In each litter (replicate), female pups at postnatal day 6 were sacrificed and used for the isolation of dental follicles to establish a DFSC culture. A total of four primary DFSC cultures were established for this study. Male littermate pups were kept until 5 months old for surgical transplantation of the DFSCs. Two rats were used in each treatment for DFSC transplantation.

Establishment of DFSC cultures

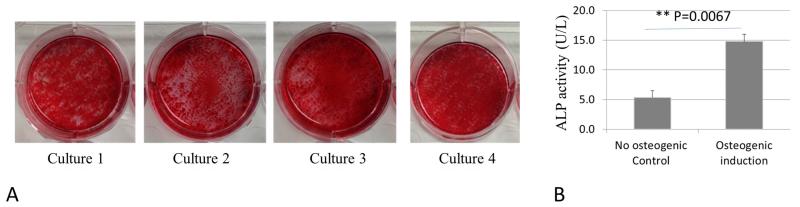

DFSCs were established as described previously (9). Briefly, DFs were surgically isolated from the first mandibular molars of the rat pups. Primary cells were obtained by trypsinization of the DFs collected from 2-3 pups of a given litter, and then cultured on plastic tissue culture flasks using a stem cell medium containing α-MEM (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) + 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA, USA) supplemented with 100 unit/ml Penicillin- 100μg/ml Streptomycin (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Non-adherent cells were removed by replacing the culture medium after overnight (about 24 hours) culture. Adherent cells were passaged at 90% confluency until passage 3. To evaluate the osteogenic capability of the established cultures, 105 cells were seeded in each well of a 6-well plate and cultured in osteogenic induction medium consisting of DMEM, 10% FBS, 50μg/mL ascorbic acid, 100nM dexamethasone and 10mM β-glycerolphosphate for 2 weeks as previously described (9, 12). The osteogenic cultures were stained with 1% Alizarin Red solution to reveal osteogenic capability of the established cells (Figure 1A). Osteogenic differentiation was confirmed by increase of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in osteogenic induced DFSCs (Figure 1B) with QuantiFluo™ ALP assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA) using 20μg of total protein from each sample. If the entire dish was heavily stained by Alizarin Red as shown in Figure 1A, the established culture was considered to possess strong osteogenic capability. The cultures showing strong osteogenic capability were collected and cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen as DFSCs. The cryopreserved-DFSCs were recovered in stem cell growth medium (α-MEM + 20% FBS) when the littermates of the donors reached the designated age for transplantation.

Figure 1.

(A) In vitro assessment of osteogenic differentiation potential of the four DFSC cultures established from 4 different litters of rat pups at passage 3. Cells were induced for osteogenic differentiation for 2 weeks, and stained with 1% Alizarin Red solution showing positive staining covering the entire wells, indicating strong osteogenic capability of the cultures that were later used for experiments in this study. (B) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) assay was performed, and a significant increase of ALP activity was seen in the DFSCs after 2 weeks of osteogenic induction as compared to the control without osteogenic induction.

Scaffold preparation and cell seeding

PCL scaffold was prepared using the following procedures. 0.8g of PCL was added to 10 ml dioxane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a glass vial. The solution was heated to 120°C and mixed until the polymer dissolved. Next the solution was poured into polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) templates and immediately incubated at −20°C for 24 hours, followed by freeze-drying at −80°C for 48 hours. This protocol generates PCL scaffolds with pore sizes of 200-300 μm. The scaffolds were processed to a diameter of 10 mm and thickness of 5 mm for in vitro experiments or a diameter of 5 mm and thickness of 0.5 mm for in vivo experiments. Prior to cell seeding, the scaffolds were sterilized with ethylene oxide.

A total of 105 cells in 100 μl stem cell growth medium was pipetted into each scaffold and incubated for 40 min to allow attachment of the cells to the scaffold. Cell-scaffold constructs were then incubated in either stem cell growth medium or osteogenic induction medium for the designated time according to different experimental purposes.

Evaluation of cell attachment loaded into scaffolds

Cell–scaffold constructs were placed in 48-well plates and incubated in 2 ml stem cell growth medium at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 3 days of incubation, the constructs were sectioned and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and 1.25% glutaraldehyde in a 0.1 M sodium carbonate (CAC) buffer, pH 7.4 for 1 hour. Next they were post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M CAC buffer for another 1 hour, followed by dehydrating through an ethanol series (30%-100%) and drying in a CO2 critical point dryer. The samples were then sputter coated with gold and subjected to scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Quanta 200 ESEM, Hillsboro, Oregon, USA) for examination of cell attachment. Scaffolds without cells were cultured and processed under the same conditions as controls.

Assessment of cell viability loaded into scaffolds

Cell–scaffold constructs were placed in 48-well plates and incubated in 2 ml stem cell growth medium. PCL scaffold without DFSCs were incubated and served as negative controls. Cell viability was evaluated after 1 and 3 days of incubation using Alamar blue reduction assay (23). Briefly, the culture medium was removed and replaced with 1 ml of assay medium consisting of α-MEM, 10% FBS and 10% Alamar blue (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY, USA). After 2 hours of incubation, 100 μl of assay medium was loaded into 96-well plates in triplicates and the optical density was read at 570 nm and 595 nm. The Alamar blue reduction was calculated using manufacturer’s protocol.

In vivo transplantation of DFSCs

SD male rats at an age of 5 months were used for in vivo DFSC transplantation study. Surgical procedures are illustrated in Figure 2. Prior to surgery, the animals were anaesthetized using isoflurane inhalation (Vet one, Boise, ID, USA). Animals were placed on a hot water blanket during the procedure to prevent hypothermia. Skin around the incision area was shaved and disinfected with Povidone-iodine 5% (Purdue Pharma, Stamford, CT, USA). An incision was made with a surgical blade from the nasofrontal area to the anterior area of the occipital protuberance. Then two 5mm-diameter full thickness defects were created around the sagittal suture with a trephine bur (XEMAX, Napa, CA, USA) and a low speed dental drill under constant irrigation with sterile saline. The operation was done carefully to avoid injuring the dura mater and underlying blood vessels. The cell–scaffold constructs were rinsed 3 times with sterile PBS buffer to remove the medium and then inserted into the defects. In each litter (cohort), animals were randomly assigned to the treatment groups (Table I). Two types of DFSCs, undifferentiated DFSCs and iDFSCs (DFSCs subjected to osteo-induction for 7 days prior to transplantation) derived from the littermates of recipient animals were used for transplantation (Table I). After transplantation, the scalp was closed using Michael clips. Following the surgery, the animals were placed in a warm and soft-bedded plastic cage for recovery. Buprenorphine (Reckitt Benckiser Healthcare Ltd, Hull, UK) of 0.05 mg/kg was administrated every 12 hours for 3 days as analgesia via intramuscular injection. Endroflaxacin (Bayer, Shawnee Mission, Kansas, USA) was added to their drinking water to prevent infection for 7 days. In each cohort (litter), animals were transplanted with the DFSCs derived from their littermates, one-half of the animals were sacrificed after 4 weeks post-operatively, and the other one half was sacrificed after 8 weeks. The skulls were harvested surgically, fixed in 10% Neutral-buffered formalin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for further analysis and examination to determine the treatment effects.

Figure 2.

Surgical procedures for transplantation of DFSCs to treat critical-size defects on rat calvarial bone. (A) Experimental rat was anaesthetized using isoflurane inhalation. (B) Skin in the incision area was shaved and disinfected with Povidone-iodine solution. (C) A midline incision was created from the nasofrontal area to the anterior area of the occipital protuberance. (D) Two 5 mm diameter defects were created using trephine bur. (E) Scaffold implants were placed into the defects. A photograph of the scaffold was shown on the lower right corner. (F) The scalp was closed using Michael clips.

Table I.

Treatment groups and bone formation determined by micro-CT analysis at week 8 after transplantation of dental follicle stem cells (DFSCs) to the rat skull defects

| Treatment Groups | Description | New Bone (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Empty control | Defect without any treatment | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| PCL only control | Transplanting scaffold without cells | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| PCL + DFSCs | The cell–scaffold constructs were incubated in stem cell growth medium for 3 days prior to transplantation |

48.9 ± 8.7* |

| PCL + iDFSCs | The cell–scaffold constructs were incubated in stem cell growth medium for 3 days followed by 7 days induction in osteogenic medium prior to transplantation |

51.33 ± 2.9* |

Single asterisk indicates significant difference at P≤0.05 when compared to the controls

Evaluation of bone regeneration

The assessment of bone regeneration was done with micro-CT and histological analysis. First, harvested skulls were assessed for new bone formation using a micro-CT imaging system (Skyscan 1074, Micro photonics, Inc., Allentown, PA, USA). The following parameters were used for examination of all samples: X-ray voltage of 40 kVp, current of 1000 μA, and exposure time of 550 milliseconds for each of the 360 rotational steps. From the micro-CT data, two-dimensional images were reconstructed using NRecon, version 1.6.9.4 (Bruker microCT, Kontich, Belgium). Next, three-dimensional images were made using CTvox, version 2.6.0 (Bruker microCT, Kontich, Belgium). Following image intensity modification, quantitative analysis of new bone formation was performed using Matlab 2013a software (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). The percentage of newly regenerated bone was calculated from the fraction of the number of voxels of new bone over the number of voxels of the entire defect.

Following micro-CT scanning, skulls were transferred to 10% Neutral-buffered formalin for about 1 week. Samples were then decalcified with Cal-Ex™ Decalcifier for 2-3 weeks (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Each defect sample was embedded with paraffin. Five μm serial sections were cut parallel to the sagittal plane. Twenty sections were prepared from each sample, and mounted on Sperfrost plus® slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The slides were treated with xylene to deparaffin. Next, one-half of the slides were stained with Eosin (H & E), and other half slides were stained with Masson Trichrome for evaluation of bone formation. For H & E staining, slides were stained in Hematoxylin solution (0.5% in distilled water) for 20 minutes followed by 1 minute of staining in Eosin (0.25% in 80% ethanol). For Masson Trichrome staining, sections were first stained in Weigert’s iron Hematoxylin working solution for 10 minutes, and then stained in Biebrich Scarlet-Acid Fuchsin for 2 minutes and Aniline Blue Solution for another 2 minutes. Digital images from stained sections were taken with an optical microscope (Olympus BX48, Center Valley, PA, USA). Quantitative analysis of new bone formation was carried out in H&E stained slides using Matlab 2013a software (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Student T-test was performed for comparison of two means. For in vivo bone regeneration analysis, statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used for comparisons of the treatment effects with P≤0.05 being statistically significant.

RESULTS

Evaluation of DFSC attachment loaded into PCL scaffold

We examined cell attachment by SEM at day 3 after loading DFSCs on scaffolds. SEM micrographs showing cell attachment at different magnifications (500×-3000×) are presented in Figure 3. Attachment and infiltration of DFSCs in the porous structure of PCL scaffold (Figure 3D-F) were observed, as compared to the control scaffold without cell attachment (Figure 3A-C).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of DFSC attachment on PCL scaffold by SEM. Scaffold structure at various magnifications without loading DFSCs (A-C), 500 × (A), 1000× (B) and 3000× (C). Various magnifications of PCL scaffold microphotographs showing attachment of DFSCs (arrows) on the scaffold (D-F), 500 × (D), 1000× (E) and 3000× (F). Note three-dimensional porous structure for attachment of DFSCs.

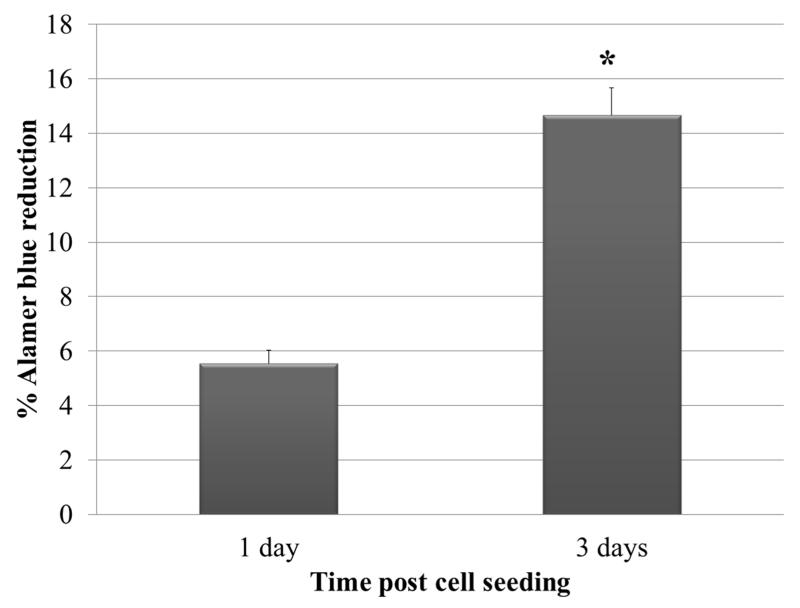

Assessment of DFSC viability/proliferation loaded into PCL scaffold

To determine if PCL scaffold is compatible for survival and growth of DFSCs, we evaluated the cell growth on the scaffolds prior to osteogenic induction. In this regard, the cell viability assay was performed during the culture in stem cell growth medium. Alamar blue reduction assay was conducted at days 1 and 3 after cell seeding into PCL to assess the cell survival and proliferation. Scaffolds without stem cells served as negative control. Significant increase of Alamar blue reduction was seen at day 3 as compared to day 1, indicating that DFSCs could survive and proliferate in the PCL scaffolds (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Assessment of viability and proliferation of DFSCs on PCL using Alamar blue assay. Note that a significant increase of Alamar blue reduction (Mean ± SE) was observed at day 3 compared to day 1. Single (*) asterisk indicates significant difference at P≤0.05 (N=4).

Micro-CT analysis of bone regeneration after transplantation of DFSCs

To assess bone regeneration, micro-CT scans were performed at weeks 4 and 8 post-transplantation. A representative micro-CT graph from each treatment group is shown in Figure 5 (N=4). At week 4 post-surgery, micro-CT scanning revealed a complete lack of bone regeneration among the defects in all treatment groups (Figure 5 upper panel). Scans at week 8 (Figure 5 lower panel) showed no bone formation in the negative control (empty control without scaffold and cells). Similarly, defects treated with scaffold only showed no bone regeneration as well. In comparison, in the defects treated with PCL with DFSCs or PCL with iDFSCs, new bone formation filled almost half of the defects.

Figure 5.

Micro-CT scanning to evaluate bone regeneration after 4 and 8 weeks of DFSC transplantation (N=4). Note the lack of bone regeneration in the defects of all treatment groups at 4 weeks (upper panel). In contrast, bone regeneration appeared at 8 weeks (Lower panel). No bone formation was seen in the controls without DFSCs, whereas in the defects treated with PCL plus DFSCs or PCL plus iDFSCs, new bone formation filled almost half of the defects.

Quantitative bone formation was acquired by analyzing the micro-CT images. Defects treated with PCL plus DFSCs or PCL plus iDFSCs showed a significant increase in the percentage of bone healing with 48.9% ± 8.7 and 51.33% ± 2.9 bone regeneration, respectively (Table I) as compared to the control of 0.00% bone formation (P<0.05). The iDFSCs gave slightly higher bone regeneration than did the DFSCs without induction; however, the difference was not statistically significant (Table I).

Histological examination of bone regeneration after transplantation of DFSCs

As radiological evaluation only shows general mineralization, we further evaluated bone healing by histological examination of bone structure. Representative slides are shown in Figures 6 and 7 (N=4). No bone regeneration was observed in all treatment groups at week 4 after transplantation (Figure 6). Defects at this time were filled with fibrous tissues as shown in Figure 6. Histological examination of week 8 specimens indicated absence of bone regeneration in the empty control defect (Figure 7A, E), as well as in the defects transplanted with scaffold only (Figure 7B, F). In comparison, substantial bone formation was observed in the defects treated with PCL plus DFSCs (Figure 7C, G) or PCL plus iDFSCs (Figure 7D, H). Formation of woven bone could be seen in those groups at higher magnification (Figure 7I, J). The appearance of new bone formation was similar to what was expected in intra-membranous ossification. The bone formation was confirmed by Masson Trichrome staining in those groups (Figure 7K, L). Quantitative analysis of bone regeneration showed no significant difference between DFSC and iDFSC treatments (Figure 7M).

Figure 6.

Histological evaluation of bone regeneration after 4 weeks post-transplantation of DFSCs with H & E staining (N=4). Low magnification micrographs showing the entire cross section of the defects (left panel), and higher magnification micrographs showing the middle of the defects (right panel). Note that no new bone formation was seen in the defects in all treatments. Fibrous tissues were seen within the defects.

Figure 7.

Histological evaluation of bone regeneration after 8 weeks post-transplantation of DFSCs (N=4). Low magnification H & E stained micrographs showing the entire defects (A-D). Note that no bone regeneration was seen in the empty control (A) and in the PCL scaffold without DFSCs (B). Substantial bone formation was seen in the defects treated with either PCL plus DFSCs (C) or PLC plus iDFSCs (D). Formation of woven bone can be seen in these treatments at higher magnifications (E, F, G, H, I and J). Sections were also stained with Masson Trichrome to confirm new bone formation (K and L). Bone histomorphometric analysis of histological sections showed no significant difference in new bone formation between DFSC and iDFSC treatments at 8 week after transplantation (M).

DISCUSSION

It has been controversial to use the term “stem cells”. By general definition, stem cells are cells that are capable of self-renewal and differentiation to become specialized cells. Cells used in this study possess these two important properties of stem cells (9). In our recent publication, we showed that these cells also express common stem cell markers, CD73, CD90, and NOTCH1 (24). In contrast, growing dental follicle derived cells in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) + Newborn Calf Serum (NCS) results in a cell population that is not capable of differentiation (9), but is expressing fibroblast markers (25). We analyzed the cell populations used in this study for their capability of differentiation and confirmed that they possessed strong osteogenic capability (Figure 1). Thus, the cell populations used in this study contain stem cells, and we use the term “dental follicle stem cells” in distinguishing from the dental fibroblast population that is incapable of differentiation. However, it was likely that the cell populations contain non stem cells such as fibroblasts as well.

Utilization of dental stem cells, such as DFSCs, has raised interest in the field of regenerative medicine. The advantages of these cells are that they can be isolated from extracted impacted teeth that are normally discarded as a medical waste during the course of dental treatment (26). Experimental data have demonstrated multipotential differentiation of DFSCs (9-11). Particularly, their strong osteogenic capability makes them an attractive type of AdSCs for repairing bone defects or bone loss in periodontal disease. In such regards, in vivo transplantation of DFSCs for bone regeneration has been attempted. DFSCs were mixed with ceramic phosphate and then transplanted subcutaneously have resulted in bone formation, indicating the in vivo bone-forming capacity of these cells (13, 14). Recent studies reported the success of transplanting DFSC pellets to heal calvarial critical-size defects in immunocompromised rats (15, 16). This study sought to extend our knowledge regarding the potential application of DFSCs for treatment of skeletal defects. Successful bone regeneration was achieved for treatment of calvarial critical-size defects of immunocompetent rats after transplanting DFSCs loaded into PCL scaffold, which are a critical step toward clinical application of DFSCs for regeneration of large defects.

Previous studies have suggested that scaffold is essential for supporting a three-dimensional structure for cell attachment and vascularization (17), particularly in treatment of large defects. In this study, we tested PCL scaffold for its compatibility to DFSCs. Our in vitro study shows that the PCL scaffold provide three-dimensional porous structure for proliferation and attachment of DFSCs. Moreover, PCL appears to support differentiation of DFSCs for bone regeneration based on the in vivo transplantation experiments. Study reported that PCL was suitable for fabrication of scaffold for bone tissue engineering using osteoblasts (27). Recent study reported that PCL scaffold coated with hyaluronic acid and β-TCP mixture supports cell proliferation and cell migration of dental pulp stem cells resulting in even cell dispersion throughout the scaffold (28). It would be interesting to determine if PCL coated with hyaluronic acid and β-TCP mixture can be used as scaffold for DFSCs to improve tissue regeneration in future studies.

Cell density on scaffold can significantly affect tissue regeneration. Bitar et al., reported that cell seeding density of 106-107 cells/cm3 on collagen scaffold resulted in optimal performance for osteoblastic differentiation (29). The scaffold used in our in vivo bone regeneration experiment was 10 mm3 (i.e, 0.01 cm3). So we loaded 105 cells onto the scaffold to yield 107cells/cm3. Further study may be needed to optimize the cell density for using DFSCs in bone regeneration with PCL-based scaffolds.

The focus of this study was to establish a protocol to evaluate the bone regeneration capability of dental follicle stem cells using immunocompetent normal rats. This study revealed that no visible bone regeneration was seen at 4 weeks after transplantation of rat DFSCs to critical-size defects, and it took as long as 8 weeks to see the healing effect. Studies using other types of AdSCs, including adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) and bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs), showed the bone healing at 4 weeks post-transplantation (4, 5). Cowan et al., reported 10% and 40% bone formation at 4 weeks after transplantation of mouse ASCs and BMSCs, respectively (4). They observed that the regenerated bone filled almost half of the defects at 8 weeks, which is similar to our observation. When human ASCs loaded on PCL scaffold were transplanted into critical-size defects of nude mice, tissue regeneration was seen at 4 weeks (30). The bone regeneration seen in our study was generally slower than the AdSC transplantation studies reported by others. This could be due to the following reasons: (A) AdSCs from different tissues and different species were transplanted; (B) immunocompromised animals were used in the reported studies, and immunocompetent animals were used in our study. Although we did not observe any inflammatory reaction in our transplantation experiments, unnoticeable immune response might exist after transplantation, causing the delay of the healing process. It would be valuable in further studies to compare the regeneration capability of DFSCs to other tissue derived stem cells, such as ASCs, BMSCs and dental pulp stem cells with this established protocol.

Various cytokines and growth factors, such as bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), are known to enhance osteogenic differentiation of AdSCs (5, 31, 32). In a human ASC transplantation study, significant improvement of bone regeneration could be achieved when recombinant BMP2 was injected to the defects after stem cell transplantation (5). Our laboratory has shown that bone morphogenetic protein 6 (BMP6) and dentin matrix protein 1(DMP1) can enhance the osteogenic differentiation of DFSCs in vitro (12, 24). It would be interesting to determine whether addition of these growth factors to scaffolds can accelerate the bone regeneration from DFSCs.

It is controversial regarding the necessity of pre-induction of AdSCs prior to transplantation (5, 33). This study determined that transplanting osteogenic pre-induced DFSCs (i.e., iDFSCs) slightly enhanced bone formation than did the DFSCs without pre-induction; however, there was no significant difference between pre-induced and non-pre-induced treatments. This suggests that pre-induction of DFSCs prior to transplantation may not be necessary.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that DFSCs are a promising cell type for repair of craniofacial defects. Our data showed that DFSCs, without prior induction, can be directly used for repairing bone defects. In addition, PCL appears to be a suitable scaffold material for seeding DFSCs for bone regeneration in repairing craniofacial defects.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by NIH/NIDCR and LSU-SVM CORP grants. Authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Kip Mathews at Department of Physics and Astronomy, Louisiana State University for providing micro-CT imaging system and for his assistance in micro-CT data collection.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AdSCs

adult stem cells

- ASCs

adipose-derived stem cells

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- ANOVA

analysis of variants

- BMPs

bone morphogenetic proteins

- BMP6

bone morphogenetic protein 6

- BMSCs

bone marrow stem cells

- CAC

sodium carbonate buffer

- DF

dental follicle

- DFSCs

dental follicle stem cells

- DMP1

dentin matrix protein 1

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- H & E

hematoxylin and eosin

- IACUC

institutional animal care and use committee

- iDFSCs

osteo-induced DFSCs

- IGF1

insulin-like growth factor 1

- LSU

Louisiana state university

- PCL

polycaprolactone

- PDMS

polydimethylsiloxane

- SD

Sprague Dawley

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- [1].Mitchell D. An introduction to oral and maxillofacial surgery. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nkenke E, Schultze-Mosgau S, Radespiel-Troger M, Kloss F, Neukam FW. Morbidity of harvesting of chin grafts: a prospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2001;12:495–502. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2001.120510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nkenke E, Radespiel-Troger M, Wiltfang J, Schultze-Mosgau S, Winkler G, Neukam FW. Morbidity of harvesting of retromolar bone grafts: a prospective study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13:514–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cowan CM, Shi YY, Aalami OO, Chou YF, Mari C, Thomas R, et al. Adipose-derived adult stromal cells heal critical-size mouse calvarial defects. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:560–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Levi B, James AW, Nelson ER, Vistnes D, Wu B, Lee M, et al. Human adipose derived stromal cells heal critical size mouse calvarial defects. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Seo BM, Sonoyama W, Yamaza T, Coppe C, Kikuiri T, Akiyama K, et al. SHED repair critical-size calvarial defects in mice. Oral Dis. 2008;14:428–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2007.01396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Khojasteh A, Eslaminejad MB, Nazarian H. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance bone regeneration in rat calvarial critical size defects more than platelete-rich plasma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:356–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zou D, Zhang Z, Ye D, Tang A, Deng L, Han W, et al. Repair of critical-sized rat calvarial defects using genetically engineered bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells overexpressing hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Stem Cells. 2011;29:1380–90. doi: 10.1002/stem.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yao S, Pan F, Prpic V, Wise GE. Differentiation of stem cells in the dental follicle. J Dent Res. 2008;87:767–71. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Handa K, Saito M, Tsunoda A, Yamauchi M, Hattori S, Sato S, et al. Progenitor cells from dental follicle are able to form cementum matrix in vivo. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:406–8. doi: 10.1080/03008200290001023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Morsczeck C, Götz W, Schierholz J, Zeilhofer F, Kühn U, Möhl C, et al. Isolation of precursor cells (PCs) from human dental follicle of wisdom teeth. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:155–65. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yao S, He H, Gutierrez DL, Rezai Rad M, Liu D, Li C, et al. Expression of bone morphogenetic protein-6 in dental follicle stem cells and its effect on osteogenic differentiation. Cells Tissues Organs. 2014;198:438–47. doi: 10.1159/000360275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Handa K, Saito M, Yamauchi M, Kiyono T, Sato S, Teranaka T, et al. Cementum matrix formation in vivo by cultured dental follicle cells. Bone. 2002;31:606–11. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00868-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yagyuu T, Ikeda E, Ohgushi H, Tadokoro M, Hirose M, Maeda M, et al. Hard tissue-forming potential of stem/progenitor cells in human dental follicle and dental papilla. Arch Oral Biol. 2010;55:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tsuchiya S, Ohshima S, Yamakoshi Y, Simmer JP, Honda MJ. Osteogenic differentiation capacity of porcine dental follicle progenitor cells. Connect Tissue Res. 2010;51:197–207. doi: 10.3109/03008200903267542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Honda MJ, Imaizumi M, Suzuki H, Ohshima S, Tsuchiya S, Satomura K. Stem cells isolated from human dental follicles have osteogenic potential. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:700–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chan BP, Leong KW. Scaffolding in tissue engineering: general approaches and tissue-specific considerations. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:467–79. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0745-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Otaki S, Ueshima S, Shiraishi K, Sugiyama K, Hamada S, Yorimoto M, et al. Mesenchymal progenitor cells in adult human dental pulp and their ability to form bone when transplanted into immunocompromised mice. Cell Biol Int. 2007;31:1191–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kweon H, Yoo MK, Park IK, Kim TH, Lee HC, Lee HS, et al. A novel degradable polycaprolactone networks for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2003;24(5):801–8. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hutmacher DW, Schantz T, Zein I, Ng KW, Teoh SH, Tan KC. Mechanical properties and cell cultural response of polycaprolactone scaffolds designed and fabricated via fused deposition modeling. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55(2):203–16. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200105)55:2<203::aid-jbm1007>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li WJ, Tuli R, Huang X, Laquerriere P, Tuan RS. Multilineage differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in a three-dimensional nanofibrous scaffold. Biomaterials. 2005;26(25):5158–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Khojasteh A, Behnia H, Hosseini FS, Dehghan MM, Abbasnia P, Abbas FM. The effect of PCL-TCP scaffold loaded with mesenchymal stem cells on vertical bone augmentation in dog mandible: a preliminary report. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2013;101(5):848–54. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.32889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ahmed SA, Gogal RM, Jr, Walsh JE. A new rapid and simple non-radioactive assay to monitor and determine the proliferation of lymphocytes: an alternative to [3H] thymidine incorporation assay. J Immunol Methods. 1994;170:211–24. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rezai Rad M, Liu D, He H, Brooks H, Xiao M, Wise GE, et al. The role of dentin matrix protein 1 (DMP1) in regulation of osteogenic differentiation of rat dental follicle stem cells (DFSCs) Archives of Oral Biology. 2015;60(4):546–56. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wise GE, Lin F, Fan W. Culture and characterization of dental follicle cells from rat molars. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;267(3):483–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00319370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Honda MJ, Imaizumi M, Tsuchiya S, Morsczeck C. Dental follicle stem cells and tissue engineering. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:541–52. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shor L, Güçeri S, Wen X, Gandhi M, Sun W. Fabrication of three-dimensional polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite tissue scaffolds and osteoblast-scaffold interactions in vitro. Biomaterials. 2007;28:5291–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jensen J, Kraft DC, Lysdahl H, Foldager CB, Chen M, Kristiansen AA, et al. Functionalization of Polycaprolactone Scaffolds with Hyaluronic Acid and β-TCP Facilitates Migration and Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells In vitro. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21(3-4):729–39. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bitar M, Brown RA, Salih V, Kidane AG, Knowles JC, Nazhat SN. Effect of cell density on osteoblastic differentiation and matrix degradation of biomimetic dense collagen scaffolds. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9(1):129–35. doi: 10.1021/bm701112w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Qureshi AT, Doyle A, Chen C, Coulon D, Dasa V, Piero FD, et al. Photo Activated miR-148b-Nanoparticle Conjugates Improve Closure of Critical Size Mouse Calvarial Defects. Acta Biomaterial. 2015;12:166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wan DC, Shi YY, Nacamuli RP, Quarto N, Lyons KM, Longaker MT. Osteogenic differentiation of mouse adipose-derived adult stromal cells requires retinoic acid and bone morphogenetic protein receptor type IB signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12335–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604849103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Levi B, James AW, Wan DC, Glotzbach JP, Commons GW, Longaker MT. Regulation of human adipose-derived stromal cell osteogenic differentiation by insulin-like growth factor-1 and platelet-derived growth factor-alpha. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:41–52. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181da8858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dudas JR, Marra KG, Cooper GM, Penascino VM, Mooney MP, Jiang S, et al. The osteogenic potential of adipose-derived stem cells for the repair of rabbit calvarial defects. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:543–48. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000210629.17727.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]