Abstract

Transplanting stem cells before birth offers an unparalleled opportunity to initiate corrective treatment for numerous childhood diseases with minimal or no host conditioning. While long-term engraftment has been demonstrated following in utero hematopoietic cellular transplantation (IUHCT) during immune quiescence, it is unclear if prenatal tolerance becomes unstable with immune activation such as during a viral syndrome. Using a murine model of IUHCT, the impact of an infection with lymphocytic choriomenigitic virus (LCMV) on prenatal allospecific tolerance was examined. The findings in this report illustrate that established mechanisms of donor-specific tolerance are strained during potent immune activation. Specifically, a transient reversal in the anergy of alloreactive lymphocytes is seen in parallel with the global immune response toward the virus. However, these changes return to baseline following resolution of the infection. Importantly, prenatal engraftment remains stable during and after immune activation. Collectively, these findings illustrate the robust nature of allospecific tolerance in prenatal mixed chimerism compared to models of postnatal chimerism and provides additional support for the prenatal approach to the treatment of congenital benign cellular disease.

Introduction

In utero hematopoietic cellular transplantation (IUHCT) benefits from the nascent milieu of the fetal environment which naturally supports the survival, engraftment, and expansion of transplanted stem cells (1–6). Most importantly, the pre-immune status of the developing fetus facilitates the recognition of the allogeneic donor cells as self resulting in durable donor-specific tolerance in developing lymphocytes which is essential for successful long-term engraftment (7, 8).

For engraftment to be durable, tolerance must logically develop in all components of the immune system. Developmental allospecific T cell tolerance relies on both the deletion of self-reactive cells in the thymus and suppressive mechanisms in the periphery (9). A failure in T cell education results in graft rejection or the development of graft-versus-host disease in a reciprocal manner. In mice, the study of T cell selection is facilitated by endogenous mammary tumor viruses (Mtv) that encode superantigens which bind specifically to TCR-β chains resulting in the effective elimination of reactive T cell subsets during normal development (10–13). In the DBA/2 → Balb/c model of IUHCT, donor Mtv-reactive TCRvβ6+ T cells were deleted to low levels in tolerant chimeras with the remaining donor-reactive clones developing functional anergy (14). Accordingly, chimeric mice were tolerant to donor-derived skin grafts and were selectively hyporesponsive toward the donor cells in mixed lymphocyte reactions (4, 15, 16).

Alternatively, natural killer (NK) cells express an array of activating and inhibitory receptors.(17) The outcome of an interaction with a target cell is determined by the summation of receptor signaling by an individual NK cell with the signals from the inhibitory receptors functioning to dominantly regulate the response. NK cells from prenatal chimeras demonstrate alterations in donor-specific inhibitory receptor expression and a defective degranulation response to the donor cells (8). The stability of these tolerogenic changes in the NK cell population hinges on the maintenance of a minimum level of circulating hematopoietic chimerism (chimerism threshold). Conversely, the in vivo elimination of host NK cells abrogates the graft rejection seen below the chimerism threshold and preserves long-term engraftment. In this way, NK cells function as a secondary barrier to prenatal engraftment and explain the clinical pattern of enhanced success in NK cell-deficient recipients of IUHCT (18–21).

While such stable life-long allospecific tolerance has been demonstrated following murine prenatal transplantation, the durability of this tolerance has not been tested in the setting of immune activation (4, 8). Indeed, infection following postnatal transplantation can result in a break in established immune tolerance. (22–24) As very few clinical cases of successful IUHCT have been reported, the impact of viral infection on allograft tolerance has not been previously described. However, given the propensity for viral syndromes in children, the study of immune activation on prenatal tolerance seems vital to the clinical application of IUHCT.

We queried whether prenatal allogeneic tolerance would be maintained during the course of viral infection in an established model of allogeneic IUHCT in which engraftment or rejection can be reliably predicted by the level of early chimerism (8). Immune activation was achieved by systemic infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV, Armstrong variant) which is known to be a potent inducer of a broad cytotoxic response capable of breaking established allogeneic tolerance in other model systems (28–31). In a departure from observations of acquired postnatal tolerance, prenatal tolerance exhibited only transient changes in donor-specific anergy in the face of potent immune activation. Consequently, this study provides new clinically-relevant information regarding the effect of immune activation following viral infection on prenatal tolerance following IUHCT.

Methods

Animals

Breeding stock for inbred strains of B6Ly5.2 (H2b, Ly5.2) and B6Ly5.1 (H2b, Ly5.1) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Balb/c (H2d, Ly5.2) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animals were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities at the animal vivarium of the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine or the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. All experimental protocols and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Iowa or the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and in compliance with the U.S. Department of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

In utero transplantation

Transplantation was performed as previously described (8). Briefly, strains were bred and females checked daily for introital plugging. Donor fetal liver cells were harvested from pregnant dams at E14 (embryonic day 14, day of plug = day 0). Using isofluorane anesthesia and sterile technique, a midline laparotomy was made and the uterus exposed. Fetuses were excised and exsanguinated in a petri dish containing cold sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Invitrogen, Gaithersburg, MD). Fetal livers were dissected in a separate petri dish, and dispersed into single-cell suspension via gentle passage through a syringe over 70μm nylon mesh strainer. Low-density mononuclear cells (LDMCs) were isolated using Ficoll density separation (Histopaque 1077, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) by centrifuging at 900g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed with sterile PBS and counted using trypan blue exclusion.

Recipient fetal mice were injected at E14. Using a surgical approach for the recipient dams, the uterus was exposed and a single-cell suspension of LDMCs in 5μL PBS was injected intrahepatically into each fetus using a 100μm beveled glass micropipette through the intact but translucent uterus. The abdomen was then closed and each pregnant dam housed individually until their delivery.

Monoclonal antibodies and flow cytometry

LDMCs were isolated from submandibular blood or spleen samples. The following mAb were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) or BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) unless otherwise specified: CD45 anti-Ly5 (30-F11), H-2Kd (SF1-1.1), CD3e (145-2C11), CD8 (53-6.7), CD4 (GK1.5), NK1.1 (PK136, kindly provided by Dr. Wayne Yokoyama, St. Louis, Missouri), DX5 (DX5), Ly49A (YE1/48; Biolegend, San Diego, CA), Ly49D(4E5), Ly49G2b6(CWY-3), CD11b (M1/70), Gr-1 (RB6-8C5), B220 (RA3-6B2), NKp46 (29A1.4), Ter119 (TER-119), Ly49F (HBF-719; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), IFN-γ (XMG1.2) and BrdU (PRB-1), CD44 (IM7), CD62L (MEL-14). T cell subsets were additionally stained using TCR vβ3 (KJ25), TCR vβ4 (KT4), TCR vβ5.1/5.2 (MR9-4), TCR vβ6 (RR4-7), TCR vβ7 (TR310), TCR vβ8.1/8.2 (MR5-2), TCR vβ9 (MR10-2), TCR vβ10 (B21.5), TCR vβ11 (RR3-15), TCR vβ12 (MR11-1), and TCR vβ17 (KJ23).

To determine proliferation, engrafter mice were injected with BrdU intraperitoneally twice daily on days 7, 8, and 9 post-infection or saline-injection. Ten days post-infection, cells were harvested and surface stains performed followed by intranuclear staining for BrdU. Briefly, cells were fixed with BD cytofix/cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) according to kit instructions then re-suspended in Fetal Bovine Serum containing 10% DMSO and frozen at −80°C overnight. Cells were thawed at 37°C, fixed again as described above before staining with anti-BrdU antibody (PRB-1).

The percentage of non-erythroid donor chimerism in the peripheral blood (PB) was calculated as the percentage of H-2Kd+ cells within the total CD45+ gate. Chimerism was defined as the presence of at least 0.2% H-2Kd+ events amongst CD45+ events. With the exception of engraftment rate determination, all chimeric animals used in this study had PB chimerism ranging from 1.9 – 14.4%. Dead cells were excluded using Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen). A minimum of 10,000 events were analyzed for each sample. Samples were analyzed on a BD LSR II and acquired using BDFACSDiva software (both from BD biosciences, San Diego, CA). Data and figures were prepared using FlowJo (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR).

LCMV infection

Confirmed chimeric mice were infected at 10 weeks of age with LCMV via an intraperitoneal injection (Armstrong strain, 500,000 PFU, kindly provided by Dr. Vladimir Badovinac, Iowa City, Iowa) or with saline control. Three days after infection, LDMCs were harvested by spleen biopsy which was well-tolerated during this early stage of infection. The chimerism level and frequency of T and NK cell phenotypes were monitored in the PB weekly. Animals were sacrificed 10 or 60 days after infection for phenotypic and functional analysis.

Intracellular cytokine assay

12-well plates were coated overnight with 10μg/ml of anti-NK1.1 mAb and washed with PBS. Splenic LDMCs were harvested from control and infected chimeric mice and then cultured at a density of 106 cells into each of the antibody-coated, uncoated and PMA/Ionomycin wells. Following a 4-hour incubation at 37° C in the presence of Brefeldin A (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), the splenocytes were harvested and extracellular staining performed prior to intracellular staining using a BD cytofix/cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences). Because antibodies against NK1.1 were used for stimulation, the percentages of NK cells that expressed IFN-gamma was determined by gating on CD3-DX5+ lymphocytes.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as the mean of each respective group, plus or minus standard deviation. Statistical comparisons were performed using a 2-tailed student t test assuming unequal variances, using Microsoft Excel software (Redmond, WA). Data sets with n = 3 were analyzed using a a non-parametric two sample Wilcoxon test using R version 3.2.0.

Results

Stable engraftment in prenatal allogeneic chimeras requires a minimum level of early chimerism

To determine the effect of immune activation on prenatal tolerance, we employed a Balb/c → B6 murine model of allogeneic IUHCT (Figure 1A) (8). In this model LDMCs harvested from Balb/c fetal liver cells are transplanted into age-matched B6 fetuses at E14. As demonstrated in Figure 1B, recipients with an initial chimerism level of 1.8% or greater at three weeks of age predictably maintained long-term engraftment (engrafters), while recipients with chimerism levels below 1.8% exhibited universal rejection (rejecters). This chimerism threshold stems from previous observation of a critical mass of donor cells required to tolerize the host (8). Long-term engraftment rates were directly proportional to the number of transplanted fetal liver cells (Figure 1C) with stable multi-lineage hematopoietic chimerism within the bone marrow in engrafter mice (Figure 1D.) Together these data demonstrate that the presence of sufficient levels of transplanted donor cells during early immune development ensures stable long-term engraftment.

Figure 1. Rejection of prenatally transplanted allografts is dependent on cell dose.

(A) Schematic representation of generation of prenatal allogeneic chimeric mice. LDMCs were isolated from Balb/c fetal livers at E14 and injected intrahepatically into age-matched B6 fetuses. Initial chimerism was assessed at 3 weeks of age and chimeras were sorted into engrafter or rejecter subgroups in relation to the previously described chimerism threshold (1.8%). (B) Engraftment rates over time demonstrating rejection in animals with initial chimerism lower than 1.8%. (C) Long-term engraftment rates (3 months of age) in animals injected with the varying number of fetal liver cells demonstrating increased engraftment with higher cell doses. (D) Lineage analysis of donor and host CD45+ populations in bone marrow of 4 month old engrafter mice. Data is gated on live donor (CD45+ H-2Kd+) or host (CD45+ H-2Kb+) events (n=3 per group).

During immune quiescence prenatal tolerance results from the stable elimination of donor-reactive T and NK cell phenotypes

Endogenous Mtv superantigens associate with I-E family MHC class II molecules (MHC-II) acting as a bridge between the antigen presenting cell and specific TCR-beta chains resulting in selection of both CD4 and CD8 T cells (32–34). When Mtv superantigens are highly-expressed self-antigens, deletion occurs at the double positive stage of thymocyte differentiation eliminating CD4 and CD8 T cells with similar efficiency (35, 36). However when lower levels of superantigen is expressed in the thymus, selection can occur at later stages with decreased efficiency (36).

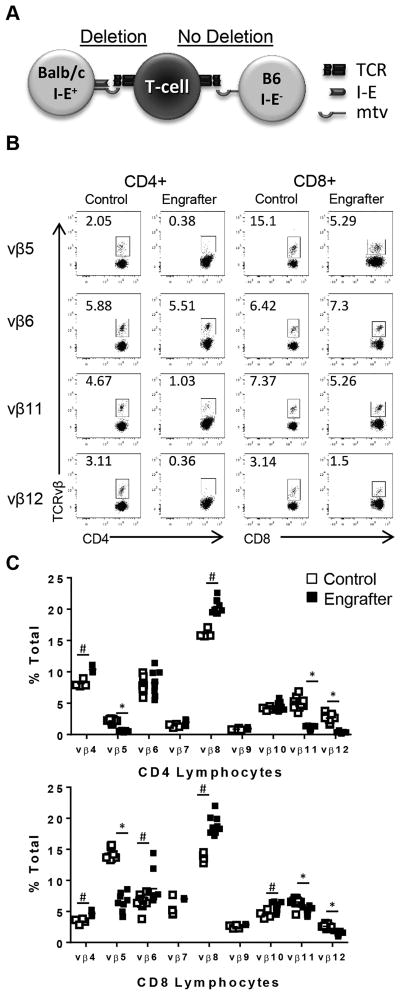

In the Balb/c→B6 model of IUHCT, it was possible to analyze selection of donor-reactive T cells specific for the Mtv-8,9 antigens associated with donor I-E MHC-II molecules (Figure 2A). Analysis of splenic T cells in ten week old animals demonstrated deletion of donor-reactive TCR vβ5, 11, and 12 in engrafter mice compared to control mice (Figure 2B, 2C) while donor-irrelevant populations were unaffected or exhibited a compensatory percent increase. As observed in other postnatal transplantation models, the reduction of Mtv-reactive CD4 T cells was more complete than reduction of CD8 T cells (37).

Figure 2. T cells specific for donor-derived Mtv-antigens are deleted in prenatally transplanted chimeras.

(A) Schematic of Mtv-mediated T cell deletion. Reactive T cell subsets are deleted in the context of I-E-positive Balb/c antigen presenting cells (APC) but not in the context of I-E-negative B6 APC. (B, C) TCR-β chain expression on CD4 and CD8 splenic T cells in control and engrafter mice. Data is gated on live CD3+ splenocytes. Representative data demonstrates that frequency of donor-reactive vβ5, 11, and 12 TCR usage is significantly diminished for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets in engrafters. * indicates significant decreases in engrafters relative to controls. # indicates significant increases in engrafters relative to controls. n = 4–8 mice per group.

NK cell tolerance to allogeneic engraftment is dependent upon the expression of activating or inhibitory donor-specific Ly49 receptors. The Ly49 gene family is composed primarily of receptors that recognize MHC class I molecules.(38) In the Balb/c →B6 murine model of allogeneic IUHCT, four host Ly49 members—Ly49A, F, G, and D—bind specifically to the Balb/c H2d MHC class I antigens (39–43). Roughly 50% of host B6 NK cells express high levels of the activating receptor Ly49D with approximately 60% of Ly49D+ NK cells co-expressing at least one of the inhibitory receptors Ly49A, Ly49F, or Ly49G (Ly49D+AFG+). Ly49D+AFG+ cells are rendered non-reactive to the Balb/c donor cells due to the co-expression of a donor-specific inhibitory receptor. Conversely, Ly49D+AFG- cells express only the activating receptor Ly49D and therefore deliver unopposed lytic signals upon recognition of the Balb/c donor cells.(44) These are referred to as “friendly” and “hostile” phenotypes respectively (Figure 3A). In engrafter mice, a significant selection bias favored friendly NK cells primarily through the elimination of hostile NK cell phenotypes in bone marrow, spleen, and blood compared to controls (Figure 3B, C, D). Despite the dramatic reduction in their frequency, hostile NK cells continued to comprise roughly 4% of the total NK cell pool, but were selectively hyporesponsive to in vitro stimulation when compared to controls (Figure 3E). Hostile NK cells from engrafter mice produced IFN-γ in response to PMA/Ionomycin similar to control mice indicating that the reduced IFN-γ production following NK1.1 stimulation was due to anergy and not exhaustion.

Figure 3. NK phenotype selection and anergy in prenatal chimeras.

(A) Schematic of NK cell selection hypothesis and basis for hostile vs. friendly NK phenotypes. Friendly NK cells co-express both the donor-reactive activating and at least one inhibitory receptor (Ly49A, Ly49F, or Ly49G). Hostile NK cells express the activating Ly49D alone. (B, C) Phenotypic analysis of BM, spleen and peripheral blood lymphocytes demonstrates selection of friendly over hostile NK cells when compared to control mice. (D) Absolute number of friendly and hostile NK cells in spleen of engrafter and control mice. (E) IFN-γ production by splenic NK cells from control and engrafter mice following in vitro stimulation with plate-bound NK1.1 antibody or PMA/Ionomycin. Data represented as the ratio of Hostile:Friendly IFN-γ production (% IFN-γ production by Ly49D+AFG- / % IFN-γ production by Ly49D+AFG+). All data is gated on NK1.1+ CD3− or DX5+CD3− lymphocytes. n = 3–4 mice per group.

Immune activation has minimal effects on the frequency, proliferation, or activation of alloreactive T cells subsets

To assess the durability of tolerance in response to immune activation, engrafter mice were infected with LCMV. LCMV-infected mice were visibly lethargic and hunched with ruffled hair, characteristic of the viral syndrome. During infection there was a robust expansion of cytotoxic CD8 T cells for several weeks compared to uninfected engrafters (Figure 4A) confirming potent immune activation as expected (45). Donor-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ TCRvβ5+, 11+, and 12+ populations were assayed for changes in frequency, proliferation, and the expression of activation markers ten days following LCMV infection. The frequency of CD4+TCRvβ5+ and CD4+TCRvβ12+ cells increased slightly with LCMV infection (Figure 4B.) In contrast, the CD4+TCRvβ11+ population did not expand with infection. However, despite the dramatic overall expansion of host CD8 T cells following infection, none of the donor-reactive CD8+ cells expanded in engrafter mice (Figure 4B). In comparison, naïve B6 mice exhibited no change in the frequency of the donor-reactive CD4+ subsets and a significant decrease in the frequency of the CD8+TCRvβ5+ subset after infection (Supplemental Figure 1A.)

Figure 4. Potent T cell activation in LCMV-infected prenatal chimeras.

(A) Dramatic expansion of CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood of engrafters following LCMV infection. (B) Frequency, (C) proliferation and (D) activation of alloreactive TCRvβ5, 11, and 12+ subsets in engrafters that were not infected compared to infected engrafters 10 days after LCMV infection. Data gated on single positive CD3+CD4+ or CD3+CD8+ events. Data represented as (C) percent positive for BrdU gated on individual alloreactive populations (TCRvβ5+ CD3+CD4+) and as a proliferation ratio (% of CD4+TCRvβ5+ cells that are BrdU+ / % of total CD4 that are BrdU+). (D) Bar graphs represent the percentage of TCRvβ5+ T cells with an activated phenotype defined as CD44HiCD62LLo or as an activation ratio (% of CD4+TCRvβ5+ that are CD44HiCD62LLo / % of total CD4 that are CD44HiCD62LLo). n = 4–9 mice per group.

Furthermore donor-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ TCRvβ5+, 11+, and 12+ cells from LCMV-infected engrafters displayed increased BrdU incorporation compared to uninfected engrafters as expected (Figure 4C). However, the relative proliferation of each donor-reactive subset amongst all CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was comparable between uninfected and LCMV-infected engrafters with the exception of the CD8+TCRvβ5+ subset which proliferated at a slightly lower rate. Similar findings were seen in naïve B6 mice before and during infection (Supplemental Figure 1B). These data indicate that the donor-reactive T cell populations proliferated at a similar rate as non-specific T cell subsets in the context of infection.

Lastly, a greater frequency of donor-reactive CD4+ and CD8+TCRvβ5+ T cells displayed an activated phenotype of CD44HiCD62LLo in LCMV-infected compared to uninfected engrafters (Figure 4D). However, the activation rate of CD4+TCRvβ5+ T cells relative to the total CD4 population (activation ratio) was lower during LCMV infection while the activation ratio of the CD8+ TCRvβ5+ cells was similar to the total CD8+ population. Donor-reactive T cell subsets in naïve B6 mice displayed a similar pattern of activation after infection (Supplemental Figure 1C) indicating that the donor-reactive T cell populations were not disproportionately activated during LCMV infection in the engrafter mice.

Immune activation does not alter NK cell selection, but transiently breaks anergy in the phenotypically hostile NK cells

Following viral infection, the frequencies of friendly or hostile NK cells and their relative ratios did not change (Figure 5A). However, during the active phase of LCMV infection, hostile NK cells from the infected engrafter mice became significantly more responsive to NK1.1 stimulation when compared to uninfected engrafter mice (Figure 5B). Clearance of LCMV occurs eight to ten days post-infection (46). Following clearance of the infection, hostile NK cells returned to their relative state of hyporesponsiveness (Figure 5B) No difference in the IFN-γ response was observed with PMA/Ionomycin stimulation during active LCMV infection or at the long-term time point confirming that exhaustion was not a factor. Collectively, these data indicated that LCMV infection resulted in a transient break in NK cell anergy without significant changes in hostile NK cell frequency.

Figure 5. Transient break in NK cell anergy following immune activation of prenatal chimeras.

(A) Frequency of friendly or hostile NK cell phenotypes in peripheral blood of prenatal engrafters prior to and seven days following immune activation. (B) Assessment of functional anergy in residual hostile NK cells. Hostile:Friendly IFN-γ production ratio in NK cells from LCMV-activated or uninfected engrafters at 3 days and 60 days post-activation following NK1.1 or PMA/Iono stimulation. All data is gated on NK1.1+ CD3− or DX5+CD3− lymphocytes (n = 3–8 mice per group).

Prenatal allogeneic engraftment is durable despite immune activation

To assess the durability of prenatal engraftment during immune activation, peripheral blood chimerism was followed in both LCMV-infected and uninfected engrafters over time. Surprisingly, chimerism was not affected by LCMV-infection (Figure 6A) indicating that prenatal tolerance is robust in the face of significant immune activation.

Figure 6. Balanced multi-lineage engraftment remains stable in prenatal chimeras through immune activation and after recovery.

(A) Analysis of PB chimerism during LCMV infection and after recovery. PB chimerism is calculated as the percentage of donor (H-2Kd+) cells amongst all CD45+ cells. Values shown for each time point represent the percentage of the original chimerism level prior to indicate treatment. (B, C) LCMV-infected engrafters were pulsed with BrdU on days 7 – 9 then analyzed on day 10 post-infection. Data is represented as the ratio of donor/host BrdU+ cell frequency for all CD45+ cells (B) or individual lineages (C) in bone marrow, spleen, and PB of engrafter mice. n = 3–14 mice per group.

To further confirm that the donor population was not targeted during immune activation, the rate of BrdU-incorporation was measured in donor and host populations during infection in engrafters. Donor cells proliferated at a similar rate in bone marrow, spleen, and blood in the unifected engrafter mice (Figure 6B). However, during LCMV infection, the donor hematopoietic cells proliferated at a similar or higher rate than the host cells in all organs tested (Figure 6B). When the analysis was focused on individual hematopoietic populations, cells, all of the donor cell lineages proliferated at the same rate as the corresponding host cells with the exception of the B220+ cells (Figure 6C). The reasons for the observed variable increase increase in the relative proliferation of donor B220+ cells remains unclear but may reflect inherent strain-specific differences in the response to LCMV infection (47). Taken together, these findings suggest that the donor cell proliferation was not negatively impacted during infection.

Discussion

The association between infections with viral, bacterial or fungal pathogens and clinical allograft rejection has been previously documented (22, 23). Supporting evidence from animal studies of postnatal hematopoietic cell transplantation have confirmed that infections around the time of transplantation can lead to increased T cell-mediated alloreactivity and graft rejection (28–31, 48–50). In these models, rejection was mediated by a failure in T cell tolerance to transplant antigens. Based on this information, we expected to see an increased frequency, proliferation, and activation of the donor-reactive T cells in prenatal engrafters subjected to LCMV infection ultimately leading to donor cell rejection. Indeed, an intense proliferative and activation response was seen in the donor-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets compared to the uninfected state. However, graft rejection was not observed. This may be due to the selectively impaired proliferation of donor-reactive CD8+ T cells or selectively limited activation of donor-reactive CD4+ T cells suggesting a persistent defect in the response of these cells to the LCMV infection when compared to the general CD4+ and CD8+ T cell population. The demonstration that the frequency of donor-reactive CD8+ T cells remained low further supports that some degree of donor-specific anergy remained during the infectious state. Collectively the analysis of the frequency, proliferation, and activation state of alloreactive T cells supports that T cell tolerance to the donor cells was maintained during LCMV infection.

A break in NK cell anergy has also been reported to occur during bacterial and viral infections warranting an examination of this mechanism in prenatal chimeras (51–53). Additionally, unlicensed NK cells have been shown to exhibit a rapid proliferate response and play a critical role in the clearance of murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) infection (53). In the current Balb/c → B6 prenatal transplantation model, unlicensed host Ly49D+AFG- NK cells would also be the principal effectors of NK cell-mediated graft rejection. Following LCMV infection, these hostile NK cell subsets exhibited a transient break in the pre-existing anergy with a return to the hyporesponsive state after the infection cleared. Along with the changes observed in T cell tolerance, this temporary reversal in NK cell tolerance was likely essential for clearance of the infection, but was potentially detrimental to engraftment. Despite this situation, we did not observe a drop in chimerism as a result of the infection suggesting that alternative tolerance mechanisms compensated for the transient break in the anergy.

One possible compensatory tolerance mechanism might include the homeostatic control of activated CD4+ T cells by LCMV-induced NK cells in the host as previously described (54). The relatively low frequency of activated CD4+ T cells measured during active infection supports this possibility. The resulting reduction in activated CD4+ T cell activity likely constrained the potent CD8+ T cell response leading to exhaustion and prevention of autoimmune diseases including the rejection of prenatal chimerism. Alternatively, it is possible that donor-reactive regulatory T cells (Tregs) provide additional protection during infection. While Tregs contract during the first week of LCMV infection, they quickly rebound by day 14, providing another mechanism for control of any alloreactive T cells generated during infection (55). The expansion in CD4+ T cells during the early phases of the LCMV infection seen in Figure 4 is consistent with this hypothesis. Further study is needed to determine if either of these mechanisms contributed to the maintenance of tolerance in prenatal chimeras during active infection.

Lastly, it is important to clarify that this study examined the durability of prenatal tolerance in engrafter mice with initial chimerism of ≥1.8%. Mice with lower initial chimerism (rejecter mice) reliably reject the transplanted cells making it difficult to assess the impact of immune activation on transplant tolerance when tolerance does not seem to exist in these animals. Further studies should explore the the short- and long-term impact of graft rejection on T and NK cell education and memory and the relevance of the inflammatory milieu to either process.

In summary, this report examines the durability of prenatal tolerance following immune activation. From this study, we conclude that prenatal tolerance in response to immune activation is characterized by stable deletion of alloreactive T cell subsets, stable selection for friendly NK phenotypes, transient reversal of hostile NK cell anergy, and durable long-term engraftment. It will be critical to evaluate the robust nature of prenatal transplantation in the face of other mechanisms of immune activation such as bacterial or fungal infections. Future work should explore additional components of the immune system in order to generate a more comprehensive understanding of prenatal tolerance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the skillful technical assistance of Bhavana Makkapati, George Tzanetakos, and Jessica Jones and statistical advice by Dr. Marepalli Rao

A.F.S. is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01HL103745 and generous support from the Children’s Hospital Research Foundation.

Abbreviations used in this article

- IUHCT

in utero hematopoietic cellular transplantation

- Ly49AFG

cell-surface expression of Ly49A or Ly49F or L49G

References

- 1.Liuba K, Pronk CJ, Stott SR, Jacobsen SE. Polyclonal T-cell reconstitution of X-SCID recipients after in utero transplantation of lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors. Blood. 2009;113:4790–4798. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flake AW, Harrison MR, Adzick NS, Zanjani ED. Transplantation of fetal hematopoietic stem cells in utero: the creation of hematopoietic chimeras. Science. 1986;233:776–778. doi: 10.1126/science.2874611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison MR, Slotnick RN, Crombleholme TM, Golbus MS, Tarantal AF, Zanjani ED. In-utero transplantation of fetal liver haemopoietic stem cells in monkeys. Lancet. 1989;2:1425–1427. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HB, Shaaban AF, Yang EY, Liechty KW, Flake AW. Microchimerism and tolerance after in utero bone marrow transplantation in mice. J Surg Res. 1998;77:1–5. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearce RD, Kiehm D, Armstrong DT, Little PB, Callahan JW, Klunder LR, Clarke JT. Induction of hemopoietic chimerism in the caprine fetus by intraperitoneal injection of fetal liver cells. Experientia. 1989;45:307–308. doi: 10.1007/BF01951819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice HE, Hedrick MH, Flake AW. In utero transplantation of rat hematopoietic stem cells induces xenogeneic chimerism in mice. Transplant Proc. 1994;26:126–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nijagal A, Derderian C, Le T, Jarvis E, Nguyen L, Tang Q, Mackenzie TC. Direct and indirect antigen presentation lead to deletion of donor-specific T cells after in utero hematopoietic cell transplantation in mice. Blood. 2013;121:4595–4602. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-463174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durkin ET, Jones KA, Rajesh D, Shaaban AF. Early chimerism threshold predicts sustained engraftment and NK-cell tolerance in prenatal allogeneic chimeras. Blood. 2008;112:5245–5253. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alpdogan O, van den Brink MR. Immune tolerance and transplantation. Semin Oncol. 2012;39:629–642. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braun MY, Jouvin-Marche E, Marche PN, MacDonald HR, Acha-Orbea H. T cell receptor V beta repertoire in mice lacking endogenous mouse mammary tumor provirus. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:857–862. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt MP, Shevach EM, Punkosdy GA. Endogenous Mouse Mammary Tumor Viruses (Mtv): New Roles for an Old Virus in Cancer, Infection, and Immunity. Front Oncol. 2013;3:287. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kappler JW, Staerz U, White J, Marrack PC. Self-tolerance eliminates T cells specific for Mls-modified products of the major histocompatibility complex. Nature. 1988;332:35–40. doi: 10.1038/332035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scherer MT, Ignatowicz L, Pullen A, Kappler J, Marrack P. The use of mammary tumor virus (Mtv)-negative and single-Mtv mice to evaluate the effects of endogenous viral superantigens on the T cell repertoire. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1493–1504. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HB, Shaaban AF, Milner R, Fichter C, Flake AW. In utero bone marrow transplantation induces donor-specific tolerance by a combination of clonal deletion and clonal anergy. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:726–729. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90364-0. discussion 729–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi S, Peranteau WH, Shaaban AF, Flake AW. Complete allogeneic hematopoietic chimerism achieved by a combined strategy of in utero hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and postnatal donor lymphocyte infusion. Blood. 2002;100:804–812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrier E, Lee TH, Busch MP, Cowan MJ. Induction of tolerance in nondefective mice after in utero transplantation of major histocompatibility complex-mismatched fetal hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 1995;86:4681–4690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:225–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wengler GS, Lanfranchi A, Frusca T, Verardi R, Neva A, Brugnoni D, Giliani S, Fiorini M, Mella P, Guandalini F, Mazzolari E, Pecorelli S, Notarangelo LD, Porta F, Ugazio AG. In-utero transplantation of parental CD34 haematopoietic progenitor cells in a patient with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (SCIDXI) Lancet. 1996;348:1484–1487. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flake AW, Roncarolo MG, Puck JM, Almeida-Porada G, Evans MI, Johnson MP, Abella EM, Harrison DD, Zanjani ED. Treatment of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by in utero transplantation of paternal bone marrow [see comments] New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;335:1806–1810. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612123352404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Archer DR, Turner CW, Yeager AM, Fleming WH. Sustained multilineage engraftment of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells in NOD/SCID mice after in utero transplantation. Blood. 1997;90:3222–3229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alhajjat AM, Lee AE, Strong BS, Shaaban AF. NK cell tolerance as the final endorsement of prenatal tolerance after in utero hematopoietic cellular transplantation. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:51. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grattan MT, Moreno-Cabral CE, Starnes VA, Oyer PE, Stinson EB, Shumway NE. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with cardiac allograft rejection and atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1989;261:3561–3566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almond PS, Matas A, Gillingham K, Dunn DL, Payne WD, Gores P, Gruessner R, Najarian JS. Risk factors for chronic rejection in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 1993;55:752–756. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199304000-00013. discussion 756–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun JC, Lanier LL. Cutting edge: viral infection breaks NK cell tolerance to “missing self”. J Immunol. 2008;181:7453–7457. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polte T, Hennig C, Hansen G. Allergy prevention starts before conception: maternofetal transfer of tolerance protects against the development of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1022–1030.e1025. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson EE, Myers RA, Du G, Aydelotte TM, Tisler CJ, Stern DA, Evans MD, Graves PE, Jackson DJ, Martinez FD, Gern JE, Wright AL, Lemanske RF, Ober C. Maternal microchimerism protects against the development of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roy E, Leduc M, Guegan S, Rachdi L, Kluger N, Scharfmann R, Aractingi S, Khosrotehrani K. Specific maternal microchimeric T cells targeting fetal antigens in β cells predispose to auto-immune diabetes in the child. J Autoimmun. 2011;36:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Welsh RM. Induction of alloreactive cytotoxic T cells by acute virus infection of mice. J Immunol. 1986;136:1186–1193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welsh RM, Markees TG, Woda BA, Daniels KA, Brehm MA, Mordes JP, Greiner DL, Rossini AA. Virus-induced abrogation of transplantation tolerance induced by donor-specific transfusion and anti-CD154 antibody. J Virol. 2000;74:2210–2218. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2210-2218.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams MA, Tan JT, Adams AB, Durham MM, Shirasugi N, Whitmire JK, Harrington LE, Ahmed R, Pearson TC, Larsen CP. Characterization of virus-mediated inhibition of mixed chimerism and allospecific tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;167:4987–4995. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams AB, Williams MA, Jones TR, Shirasugi N, Durham MM, Kaech SM, Wherry EJ, Onami T, Lanier JG, Kokko KE, Pearson TC, Ahmed R, Larsen CP. Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1887–1895. doi: 10.1172/JCI17477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fortin JS, Genève L, Gauthier C, Shoukry NH, Azar GA, Younes S, Yassine-Diab B, Sékaly RP, Fremont DH, Thibodeau J. MMTV superantigens coerce an unconventional topology between the TCR and MHC class II. J Immunol. 2014;192:1896–1906. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kappler JW, Roehm N, Marrack P. T cell tolerance by clonal elimination in the thymus. Cell. 1987;49:273–280. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acha-Orbea H, MacDonald HR. Superantigens of mouse mammary tumor virus. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheard MA, Sharrow SO, Takahama Y. Synchronous deletion of Mtv-superantigen-reactive thymocytes in the CD3(medium/high) CD4(+)CD8(+) subset. Scand J Immunol. 2000;52:550–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2000.00814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morishima C, Norby-Slycord C, McConnell KR, Finch RJ, Nelson AJ, Farr AG, Pullen AM. Expression of two structurally identical viral superantigens results in thymic elimination at distinct developmental stages. J Immunol. 1994;153:5091–5103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wekerle T, Sayegh MH, Hill J, Zhao Y, Chandraker A, Swenson KG, Zhao G, Sykes M. Extrathymic T cell deletion and allogeneic stem cell engraftment induced with costimulatory blockade is followed by central T cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 1998;187:2037–2044. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schenkel AR, Kingry LC, Slayden RA. The ly49 gene family. A brief guide to the nomenclature, genetics, and role in intracellular infection. Front Immunol. 2013;4:90. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karlhofer FM, Ribaudo RK, Yokoyama WM. MHC class I alloantigen specificity of Ly-49+ IL-2-activated natural killer cells. Nature. 1992;358:66–70. doi: 10.1038/358066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Whitman MC, Natarajan K, Tormo J, Mariuzza RA, Margulies DH. Binding of the natural killer cell inhibitory receptor Ly49A to its major histocompatibility complex class I ligand. Crucial contacts include both H-2Dd AND beta 2-microglobulin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1433–1442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mason LH, Ortaldo JR, Young HA, Kumar V, Bennett M, Anderson SK. Cloning and functional characteristics of murine large granular lymphocyte-1: a member of the Ly-49 gene family (Ly-49G2) J Exp Med. 1995;182:293–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanke T, Takizawa H, McMahon CW, Busch DH, Pamer EG, Miller JD, Altman JD, Liu Y, Cado D, Lemonnier FA, Bjorkman PJ, Raulet DH. Direct assessment of MHC class I binding by seven Ly49 inhibitory NK cell receptors. Immunity. 1999;11:67–77. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mason LH, Anderson SK, Yokoyama WM, Smith HR, Winkler-Pickett R, Ortaldo JR. The Ly-49D receptor activates murine natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2119–2128. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.George TC, Mason LH, Ortaldo JR, Kumar V, Bennett M. Positive recognition of MHC class I molecules by the Ly49D receptor of murine NK cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:2035–2043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cousens LP, Orange JS, Biron CA. Endogenous IL-2 contributes to T cell expansion and IFN-gamma production during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J Immunol. 1995;155:5690–5699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wherry EJ, Blattman JN, Murali-Krishna K, van der Most R, Ahmed R. Viral persistence alters CD8 T-cell immunodominance and tissue distribution and results in distinct stages of functional impairment. J Virol. 2003;77:4911–4927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4911-4927.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oldstone MB, Buchmeier MJ, Doyle MV, Tishon A. Virus-induced immune complex disease: specific anti-viral antibody and C1q binding material in the circulation during persistent lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. J Immunol. 1980;124:831–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chong AS, Alegre ML. Transplantation tolerance and its outcome during infections and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2014;258:80–101. doi: 10.1111/imr.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brehm MA, Daniels KA, Priyadharshini B, Thornley TB, Greiner DL, Rossini AA, Welsh RM. Allografts stimulate cross-reactive virus-specific memory CD8 T cells with private specificity. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1738–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nahill SR, Welsh RM. High frequency of cross-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes elicited during the virus-induced polyclonal cytotoxic T lymphocyte response. J Exp Med. 1993;177:317–327. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez NC, Treiner E, Vance RE, Jamieson AM, Lemieux S, Raulet DH. A subset of natural killer cells achieves self-tolerance without expressing inhibitory receptors specific for self-MHC molecules. Blood. 2005;105:4416–4423. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tay CH, Welsh RM, Brutkiewicz RR. NK cell response to viral infections in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:780–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orr MT, Murphy WJ, Lanier LL. ‘Unlicensed’ natural killer cells dominate the response to cytomegalovirus infection. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:321–327. doi: 10.1038/ni.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waggoner SN, Cornberg M, Selin LK, Welsh RM. Natural killer cells act as rheostats modulating antiviral T cells. Nature. 2012;481:394–398. doi: 10.1038/nature10624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srivastava S, Koch MA, Pepper M, Campbell DJ. Type I interferons directly inhibit regulatory T cells to allow optimal antiviral T cell responses during acute LCMV infection. J Exp Med. 2014;211:961–974. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.