In 1976, the noted tobacco researcher, Michael Russell stated that, “People smoke for the nicotine but they die from the tar”,1 thereby suggesting a potential regulatory pathway to eliminate the key harms arising from tobacco use. That is, by reducing or eliminating nicotine from combustible tobacco products, we could dramatically reduce their use and dependence on them, essentially precluding their harms.

More than 30 years after Professor Russell’s observation, in June 2009, President Obama signed legislation that permits the reduction of levels of the primary addictive agent in tobacco: nicotine. Section 917 of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act2 states that the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) shall provide advice, information, and recommendations to the Secretary of Health and Human Services on several issues including “the effects of the alteration of the nicotine yields from tobacco products” and “whether there is a threshold level below which nicotine yields do not produce dependence on the tobacco product involved”. That legislation also contained a provision that precludes the FDA from, “requiring the reduction of nicotine yields of a tobacco product to zero.”

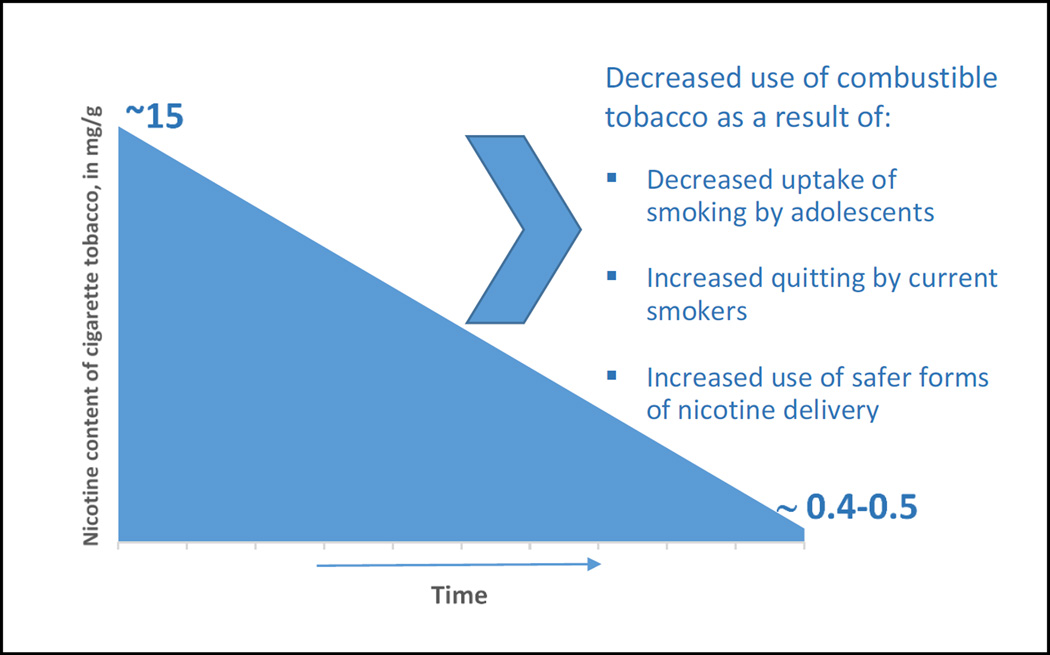

Benowitz and Henningfield were the first to propose a systematic reduction in nicotine content as a means of weaning Americans off cigarettes. In their landmark 1994 New England Journal of Medicine publication,3 the authors estimated that, “an absolute limit of 0.4 to 0.5 mg of nicotine per cigarette should be adequate to prevent or limit the development of addiction…” Note that such very low-nicotine cigarettes would be fundamentally different from earlier “light” or “low tar/nicotine” cigarettes in that the tobacco itself would contain so little nicotine that smokers could not extract significant levels no matter how they smoked. In contrast, “Light” cigarettes developed and marketed by the tobacco industry in the 1970s and 1980s included design features that smokers were able to compensate for (e.g., covering the ventilation holes) to obtain more nicotine.

Benowitz and Henningfield’s nicotine reduction proposal is intended to both prevent the development of tobacco dependence among young people and wean current smokers off cigarettes. Their premise, supported by considerable research, is that smokers will not smoke very low nicotine-yield cigarettes chronically.4 The proposed reduction is to occur gradually so as to minimize the hardship of withdrawal amongst current smokers; recent research, though, suggests that a long weaning period may be unnecessary. In addition, because of evidence that smokers will certainly use other combustible tobacco to supplement low-nicotine cigarettes if it is available,5 it seems necessary that a nicotine reduction policy should encompass all types of combustible tobacco.

Reducing the nicotine content of combustible tobacco has risks. For instance, those already addicted to conventional cigarettes might compensate for a reduced nicotine yield by smoking more cigarettes or smoking them more intensively. Such compensation might increase smokers’ exposure to the harmful toxicants of combusted tobacco, including tar, carcinogens, and carbon monoxide. However, studies, including the Donny study in this issue of the Journal, tend to show only modest compensation in response to a reduction in nicotine yield.6 Also, as the nicotine yield of combustible cigarettes declines, addicted smokers might switch to other nicotine containing products, including smokeless tobacco products and/or electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) such as e-cigarettes, e-cigars, and e-pipes. This might represent a net health benefit, though, to the extent that such products are less harmful than combustible tobacco. Such products might sustain nicotine dependence, however, and encourage continued use of low-nicotine cigarettes. It is not known how frequent such sustained “dual use” would be, nor its health consequences. Finally, new product development (e.g., an FDA approved agent that safely and effectively delivers nicotine to the alveolar bed) might further accelerate a decline in combustible cigarette use and change the risk/benefit ratio.

The paper by Donny and colleagues in this issue of the Journal7 adds to a growing literature supporting the feasibility and potential benefits of a national nicotine reduction policy, one that promises to end the devastating health consequences of combustible tobacco use. Specifically, it shows that in comparison with smokers of standard strength cigarettes (containing 15.8 mg nicotine/g tobacco), regular smokers who switched to very low-nicotine cigarettes (i.e., 0.4mg/gram) for six weeks, showed reductions in nicotine exposure, cigarettes smoked, and nicotine dependence. Moreover, they attempted to quit smoking at a rate double that of participants smoking standard strength cigarettes (34.7% vs. 17% at 30 day follow-up). These data not only support a national nicotine reduction policy, but they also suggest that additional attention be paid to low-nicotine cigarettes as a potential clinical smoking cessation resource.

Of course, as Donny et al.7 note, such results do not necessarily reflect what would occur over much longer use of low-nicotine cigarettes,5 in a broader population, with the possibility of dual use of other nicotine delivery systems, and when there is no prospect of access to higher nicotine content cigarettes (as would occur if all combustible tobacco products were low-nicotine). It is also difficult to know the extent to which manufacturers and smokers could “game the system” by modifying their tobacco products (e.g., sell high-nicotine “black market” cigarettes, spike low-nicotine cigarettes with more nicotine). Such uncertainty does not counterpoise the substantial promise of a national nicotine reduction strategy: the promise to prevent another generation of young Americans from becoming dependent on cigarettes, and the promise to slash smoking prevalence because inveterate smokers would abstain entirely, or replace combustible cigarettes with presumably safer alternatives such as nicotine replacement medications, ENDS, and smokeless tobacco products.

Thus, a nicotine reduction policy should be evaluated with regard to a “continuum of risk” across the available commercial and medicinal products that contain nicotine. As current FDA Center for Tobacco Products Director, Mitch Zeller stated in 2013 (prior to assuming his current position), “Anyone who would ponder the endgame must acknowledge that the continuum of risk exists and pursue strategies that are designed to drive consumers from the most deadly and dangerous to the least harmful forms of nicotine delivery”.8 In a related publication, Dorothy Hatsukami, an author of the Donny study, also highlighted the need to provide smokers with safer alternatives to combustible tobacco, “Reducing nicotine in cigarettes, establishing increasingly strict standards for toxicants in non-combusted tobacco products, and establishing standards to make all tobacco products less appealing may facilitate the development of less harmful methods of nicotine delivery by the industry, including devices or products that rapidly deliver nicotine without the toxicants”.9 Transitioning smokers to the use of less harmful nicotine delivery routes would be greatly advanced if the makers of reputed reduced harm products (e.g., e-cigarettes) would seek FDA approval for their products: approval based on evidence that their products are safe and effective as smoking cessation aids and that they yield benefit at both the individual and population levels.

In sum, if people smoke for the nicotine but die from the tar (arising from tobacco combustion), why not disassociate the two? Reducing the nicotine content of combustible tobacco products should undercut the motivation to smoke; therefore, young people might continue to experiment with cigarettes, but would not become dependent on them. And, adult smokers would likely either quit using nicotine or would get their nicotine from another source that is markedly safer (Figure).

Figure 1.

Potential Effects of a Nicotine Reduction Policy for Combustible Tobacco

Smoking prematurely kills half of the people who engage in it long-term: on average, robbing them of 10 –15 years of life.10 Applying those grim statistics to the current population of American smokers means that at least 20 million people will die prematurely if they continue to smoke. Reducing the nicotine content of combustible tobacco to levels that will not sustain dependence appears to be the most promising, extant regulatory policy option for preventing 20 million premature American deaths.

Contributor Information

Michael C. Fiore, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention, 1930 Monroe Street, Suite 200, Madison, WI 53711.

Timothy B. Baker, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention, 1930 Monroe Street, Suite 200, Madison, WI 53711.

References

- 1.Russell M. Low-tar medium-nicotine cigarettes: a new approach to safer smoking. BMJ. 1976;1:1430–1433. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6023.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act-Public Law No. 111-31. 2009;2012(5/14) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benowitz NL, Henningfield JE. Establishing a nicotine threshold for addiction – The implications for tobacco regulation. New Engl J Med. 1994;331:123–125. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407143310212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henningfield JE, Benowitz NL, Slade J, Houston TP, Davis RM, Deitchman SD for the Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association. Reducing the addictiveness of cigarettes. Tob Control. 1998;7:281–282. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benowitz NL, Nardone N, Dains KM, et al. Effect of reducing the nicotine content of cigarettes on cigarette smoking behavior and tobacco smoke toxicant exposure: 2-year follow up. Addiction. 2015 doi: 10.1111/add.12978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benowitz NL, Henningfield JE. Reducing the nicotine content to make cigarettes less addictive. Tob Control. 2013;22:i14–i17. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donny EC, Denlinger RL, Tidey JW, et al. Reduced nicotine standards for cigarettes: A randomized trial. New Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1502403. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeller M. Reflections on the “endgame” for tobacco control. Tob Control. 2013;22:i40–i41. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatsukami DK. Ending tobacco-caused mortality and morbidity: the case for performance standards for tobacco products. Tob Control. 2013;22:i36–i37. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: USDHS Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. The health consequences of smoking: 50 years of progress. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]