Significance

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) is a well-studied cellular process in yeast and mammalian systems. Recent molecular and genetic studies in the reference plant Arabidopsis have revealed that ERAD also is conserved in plants. Here we report that an Arabidopsis ERAD process for degrading misfolded/mutant receptor-like kinases requires a plant-specific protein, ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized brassinosteroid-insensitive 1 suppressor 7 (EBS7), that is localized to the ER membrane and is induced by ER stress. Our biochemical studies suggest that EBS7 functions as a key regulator of this Arabidopsis ERAD process by maintaining the protein stability of its core component, a membrane-anchored E3 ligase, Arabidopsis thaliana HMG-CoA reductase degradation 1a (AtHrd1a).

Keywords: brassinosteroid receptor BRI1, ERAD, EMS-mutagenized bri1 suppressor, ubiquitin ligase E3, unfolded protein response

Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) is an essential part of an ER-localized protein quality-control system for eliminating terminally misfolded proteins. Recent studies have demonstrated that the ERAD machinery is conserved among yeast, animals, and plants; however, it remains unknown if the plant ERAD system involves plant-specific components. Here we report that the Arabidopsis ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized brassinosteroid-insensitive 1 suppressor 7 (EBS7) gene encodes an ER membrane-localized ERAD component that is highly conserved in land plants. Loss-of-function ebs7 mutations prevent ERAD of brassinosteroid insensitive 1-9 (bri1-9) and bri1-5, two ER-retained mutant variants of the cell-surface receptor for brassinosteroids (BRs). As a result, the two mutant receptors accumulate in the ER and consequently leak to the plasma membrane, resulting in the restoration of BR sensitivity and phenotypic suppression of the bri1-9 and bri1-5 mutants. EBS7 accumulates under ER stress, and its mutations lead to hypersensitivity to ER and salt stresses. EBS7 interacts with the ER membrane-anchored ubiquitin ligase Arabidopsis thaliana HMG-CoA reductase degradation 1a (AtHrd1a), one of the central components of the Arabidopsis ERAD machinery, and an ebs7 mutation destabilizes AtHrd1a to reduce polyubiquitination of bri1-9. Taken together, our results uncover a plant-specific component of a plant ERAD pathway and also suggest its likely biochemical function.

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) is an integral part of an ER-mediated protein quality-control system in eukaryotes, which permits export of only correctly folded proteins but retains misfolded proteins in the ER for repair via additional folding attempts or removal through ERAD. Genetic and biochemical studies in yeast and mammalian cells have revealed that the core ERAD machinery is highly conserved between yeast and mammals and that ERAD involves four tightly coupled steps: substrate selection, retrotranslocation through the ER membrane, ubiquitination, and proteasome-mediated degradation (1, 2).

Because the great majority of secretory/membrane proteins are glycosylated in the ER, diversion of most ERAD substrates from their futile folding cycles into ERAD is initiated through progressive mannose trimming of their asparagine-linked glycans (N-glycans) by ER/Golgi-localized class I mannosidases, including homologous to α-mannosidase 1 (Htm1) and its mammalian homologs ER degradation-enhancing α-mannosidase-like proteins (EDEMs) (3). The processed glycoproteins are captured by two ER resident proteins, yeast amplified in osteosarcoma 9 (OS9 in mammals) homolog (Yos9) and HMG-CoA reductase degradation 3 (Hrd3) [suppressor/enhancer of Lin-12–like (SEL1L) in mammals], which recognize the mannose-trimmed N-glycans and surface-exposed hydrophobic amino acid residues, respectively (4, 5). The selected ERAD clients are delivered to an ER membrane-anchored ubiquitin ligase (E3), which is the core component of the ERAD machinery (6), for polyubiquitination. Yeast has two known ERAD E3 ligases, Hrd1 and degradation of alpha 10 (Doa10), both containing a catalytically active RING finger domain, whereas mammals have a large collection of ER membrane-anchored E3 ligases, including Hrd1 and gp78 (7). The yeast Hrd1/Doa10-containing ERAD complexes target different substrates, with the former ubiquitinating substrates with misfolded transmembrane or luminal domains and the latter acting on clients with cytosolic structural lesions (8).

Because of the cytosolic location of the E3′s catalytic domain and proteasome, all ERAD substrates must retrotranslocate through the ER membrane. It is well known that the retrotranslocation step is tightly coupled with substrate ubiquitination and is powered by an AAA-type ATPase, cell division cycle 48 (Cdc48) in yeast and p97 in mammals. However, the true identity of the retrotranslocon remains controversial. Earlier studies implicated the secretory 61 (Sec61) translocon, degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum 1 (Der1) [Der1-like proteins (Derlins) in mammals], and Hrd1 in retrotranslocating ERAD substrates (9). After retrotranslocation, ubiquitinated ERAD clients are delivered to the cytosolic proteasome with the help of Cdc48/p97 and their associated factors for proteolysis (10). In addition to the above-mentioned proteins, the yeast/mammalian ERAD systems contain several other components, including several ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2), a membrane-anchored E2-recruiting factor, Cue1 that has no mammalian homolog, a scaffold protein U1-Snp1–associating 1 (Usa1) [homocysteine-induced ER protein (HERP) in mammals] of the E3 ligases, and a membrane-anchored Cdc48-recruiting factor, Ubx2 (Ubxd8 in mammals) (6).

For many years ERAD has been known to operate in plants (11), but the research on the plant ERAD pathway lagged far behind similar studies in yeast and mammalian systems. Recent molecular and genetic studies in the reference plant Arabidopsis, especially two Arabidopsis dwarf mutants, brassinosteroid-insensitive 1-5 (bri1-5) and bri1-9, carrying ER-retained mutant variants of the brassinosteroid receptor (BR) BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE 1 (BRI1) (12–14), revealed that the ERAD system also is conserved in plants (reviewed in refs. 15 and 16). For example, the ERAD N-glycan signal to mark misfolded glycoproteins in Arabidopsis was found to be the same as that in yeast/mammalian cells (17, 18). Both forward and reverse genetic studies have shown that Arabidopsis homologs of the yeast/mammalian ERAD components, including Yos9/OS9 (19, 20), Hrd3/Sel1L (21, 22), Hrd1 (21), EDEMs (23), and a membrane-anchored E2 (24), are involved in degrading misfolded glycoproteins. However, it remains unknown if the plant ERAD requires one or more plant-specific components to degrade terminally misfolded proteins efficiently. In this study, we took a forward genetic approach to identify a novel Arabidopsis ERAD mutant, ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized bri1 suppressor 7 (ebs7), and subsequently cloned the corresponding EBS7 gene. We discovered that EBS7 encodes an ER-localized membrane protein that is highly conserved in land plants but lacks a homolog in yeast or mammals. Our biochemical studies strongly suggested that EBS7 plays a key role in an Arabidopsis ERAD process by regulating the protein stability of the Arabidopsis thaliana HRD1a (AtHrd1a).

Results

The ebs7-1 Mutation Restores BR Sensitivity to bri1-9 by Blocking Degradation of Its Mutant BR Receptor.

We previously showed that the dwarf phenotype of a BR-insensitive mutant, bri1-9, was caused by ER retention and subsequent ERAD of a structurally defective but biochemically competent BR receptor, bri1-9 (12, 13, 17). A genetic screen for extragenic bri1-9 suppressors coupled with a secondary screen for bri1-9–accumulating mutants revealed a conserved ERAD N-glycan signal and also identified several conserved components of an Arabidopsis ERAD system (15, 19, 21). This study is focused on a new mutant, ebs7-1. As shown in Fig. 1A, ebs7-1 bri1-9 accumulated a higher level of bri1-9 than the parental bri1-9 mutant (Fig. 1A). A simple cycloheximide (CHX)-chase experiment revealed that the observed increase in bri1-9 abundance was caused largely by attenuated degradation rather than by increased biosynthesis of bri1-9 (Fig. 1B). Similar to observations in other known Arabidopsis ERAD mutants (17–19, 21), the accumulation of bri1-9 in the ER likely saturates its ER retention systems, leading to detection of a small percentage of bri1-9 proteins carrying the complex type (CT) N-glycans (indicative of ER escape) that are resistant to hydrolysis by endoglycosidase H (Endo H), which is capable of cleaving high-mannose-type (HM) N-glycans of ER-localized proteins but not Golgi-processed CT N-glycans (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the Endo H result, a confocal microscopic analysis of the root fluorescent signals of the GFP-tagged bri1-9 revealed increased bri1-9–GFP abundance and enhanced fluorescent signal on the plasma membrane (PM) in a pBRI1:bri1-9–GFP/bri1-9 ebs7-1 transgenic line as compared with a pBRI1:bri1-9–GFP/bri1-9 EBS7+ line generated by crossing the pBRI1:bri1-9-GFP/bri1-9 ebs7-1 line with bri1-9 (Fig. S1 A and B).

Fig. 1.

The ebs7-1 mutation suppresses bri1-9 and restores its BR sensitivity by blocking bri1-9 degradation. (A) Immunoblot analysis of BRI1/bri1-9. Total proteins of 2-wk-old seedlings were treated with or without Endo H, separated by SDS/PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblot with a BRI1 antibody. bri1-9HM and bri1-9CT denote BRI1/bri1-9 proteins carrying HM and CT N-glycans, respectively. (B) Immunoblot analysis of the bri1-9 stability. Two-week-old seedlings were treated with 180 μM CHX for the indicated hours, and extracted proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with the anti-BRI1 antibody. (C–E) Pictures of 4-wk-old light-grown (C) and 5-d-old dark-grown (D) seedlings, and 2-mo-old soil-grown plants (E). (F) The BR-induced root inhibition assay. Root lengths of ∼40 7-d-old seedlings grown on BL-containing 1/2 Murashiga and Skoog (MS) medium were measured, and measurements were converted into percentage values relative to that of the same genotype grown on medium without BL. Error bars represent ± SE of three independent assays. (G) The BR-induced BES1 dephosphorylation assay. Protein extracts of 2-wk-old seedlings treated with or without 1 μM BL were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with an anti-BES1 antibody. In A, B, and G, Coomassie blue staining of the small subunit of the ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCo, hereafter RbcS) enzyme on a duplicate gel was used as a loading control.

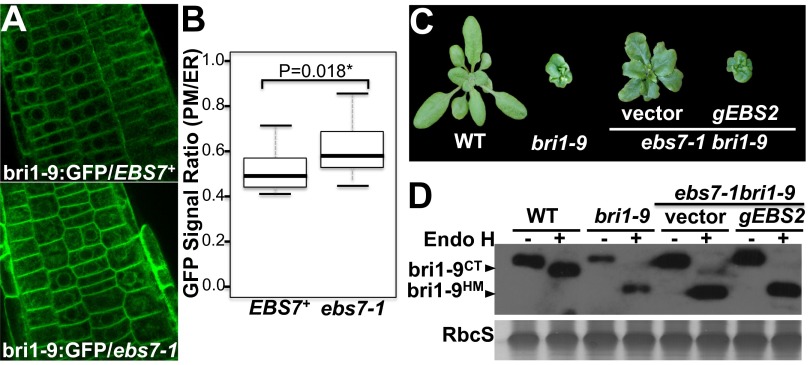

Fig. S1.

Overexpression of EBS2 nullifies the suppressive effect of the ebs7-1 mutation on bri1-9 dwarfism. (A) The confocal images of root cells transgenically expressing bri1-9–GFP in the EBS7+ (Left) and ebs7-1 (Right) background. (B) Quantitative analysis of the ratio of the GFP signal on the PM and in the ER. ImageJ was used to quantify the GFP signal in the PM and ER. In each picture in A, the average integrated fluorescent density of 15 cells was measured for the whole cell (ER and PM) and the cytosol (ER) to calculate the GFP[PM]/GFP[ER] ratio. The box-and-whisker plot was generated to show the difference between the EBS7+ and ebs7-1 genotypes, and the indicated P value was calculated by a one-tailed two-sample t test. It is important to note that the GFP[PM]/GFP[ER] ratios presented here are high, likely caused by tethering of the cortical ER with the PM. (C) Pictures of 4-wk-old soil-grown wild-type and bri1-9 plants and two transgenic ebs7-1 bri1-9 mutants carrying an empty vector or a genomic EBS2 transgene. (D) Immunoblot analysis of BRI1/bri1-9. Total proteins extracted from 2-wk-old Arabidopsis seedlings of the genotypes shown in B were treated with or without Endo H, separated by SDS/PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblot with an anti-BRI1 antibody. bri1-9HM and bri1-9CT denote the BRI1/bri1-9 proteins carrying the HM and CT N-glycans, respectively. Coomassie blue staining of RbcS on a duplicated gel serves as a loading control.

Morphologically, ebs7-1 bri1-9 has a larger rosette with much bigger rosette leaves than bri1-9 (Fig. 1C). The double mutant also has a longer hypocotyl when grown in the dark and taller inflorescence stems at maturity than bri1-9 (Fig. 1 D and E). Consistent with the detection of a small pool of ER-escaping bri1-9, ebs7-1 bri1-9 partially regains the BR sensitivity. As shown in Fig. 1F, exogenously applied brassinolide (BL) inhibited the root growth of wild-type and ebs7-1 bri1-9 plants in a dose-dependent manner but had a much weaker impact (especially at concentrations <10 nM) on bri1-9 roots. The regained BR sensitivity in ebs7-1 bri1-9 was confirmed by a widely used biochemical assay that measured the BR-induced dephosphorylation of bri1-EMS-suppressor 1 (BES1), a key transcription factor of BR signaling (25). Fig. 1G shows that BL had a marginal effect on the BES1 phosphorylation status in bri1-9 but efficiently and partially dephosphorylated BES1 in wild-type and ebs7-1 bri1-9 seedlings, respectively. Importantly, overexpression of EBS2, a limiting component of the bri1-9’s ER-retention systems (12), fully retained bri1-9 in the ER (Fig. S1D) and nullified the suppressor activity of ebs7-1 on bri1-9 (Fig. S1C).

ebs7-1 Inhibits the Degradation of Other ERAD Substrates.

To determine if ebs7-1 inhibits the degradation of other known Arabidopsis ERAD clients, we first crossed ebs7-1 into bri1-5 that carries a different ER-retained mutant BR receptor, bri1-5 (14). As shown in Fig. 2A, ebs7-1 suppressed the dwarfism of bri1-5 (Fig. 2 A and B and Fig. S2A), restored its BR sensitivity (Fig. 2 C and D), and greatly elevated the bri1-5 level (Fig. 2E). The crucial role of EBS7 in ERAD of bri1-5 was confirmed further by the identification of two allelic ebs7 mutants in an independent genetic screen for ERAD mutants of bri1-5 (Fig. S2 B and C).

Fig. 2.

ebs7-1 inhibits the degradation of bri1-5 and misfolded EFR. (A and B) Pictures of 4-wk-old light-grown (A) and 5-d-old dark-grown (B) seedlings. In (B), three individual images of two seedlings (separated by white lines) were assembled together. (C) The root-growth inhibition assay of wild-type, bri1-5, and ebs7-1 bri1-5 seedlings. (D) The BES1 dephosphorylation assay. (E) Immunoblot analysis of BRI1/bri1-5 abundance. bri1-5HM and bri1-5CT denote the BRI1/bri1-5 proteins carrying the HM and CT N-glycans, respectively. (F) Immunoblot analysis of EFR. Protein extracts of 2-wk-old seedlings were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with an anti-EFR antibody. In D and E, Coomassie blue staining of the RbcS band on a duplicate gel serves as a loading control, and in F, a nonspecific cross-reacting band indicated by the asterisk serves as a loading control.

Fig. S2.

Screen for bri1-5 suppressors identified two additional ebs7 alleles. (A) Pictures of 2-mo-old soil-grown wild-type, bri1-5, and ebs7-1 bri1-5 plants. (B) Pictures of 4-wk-old wild-type (Ws-2), bri1-5, ebs7-1 bri1-5, ebs7-2 bri1-5, and ebs7-3 bri1-5 plants. (C) Immunoblot analysis of EBS7 protein. Total proteins extracted from 2-wk-old seedlings of the genotypes shown in B were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with an affinity-purified anti-EBS7 antibody. Coomassie blue staining of RbcS on a duplicated gel serves as a loading control. (D) The full image of the immunoblot presented in Fig. 3D. Arrowheads on the left indicate the positions of the molecular weight standards and EBS7. The asterisk denotes a nonspecific band recognized by the affinity-purified EBS7 antibody.

We also examined the effect of ebs7-1 on ERAD of the ER-retained conformer of EF-Tu receptor (EFR), an Arabidopsis PM-localized immunity receptor that recognizes and binds the bacterial translation elongation factor EF-Tu (26). Previous studies demonstrated that the proper folding of EFR requires an Arabidopsis ER quality-control system consisting of EBS1 and EBS2 [also known as “priority in sweet life2 (PSL2)/elf18-insensitive21” (PSL2/ELFIN21) and PSL1/ELFIN5 (27, 28), respectively] and that their loss-of-function mutations cause misfolding, ER retention, and ERAD of EFR (29). We crossed ebs7-1 into ebs1-3 bri1-9 and analyzed the EFR abundance in both ebs1-3 bri1-9 and ebs7-1 ebs1-3 bri1-9 mutants using an anti-EFR antibody. As shown in Fig. 2F, although no EFR was detected in ebs1-3 bri1-9, the EFR abundance in ebs1-3 ebs7-1 bri1-9 mutants was similar to that in wild type, bri1-9, or ebs7-1 bri1-9 plants, indicating that EBS7 also is required for degrading misfolded EFR. Taken together, our data demonstrated that EBS7 is required for the degradation of both mutant BR receptors and misfolded EFR.

Molecular Cloning and Characterization of the EBS7 Gene.

To understand how ebs7-1 affects the Arabidopsis ERAD system, we positionally cloned the EBS7 gene. PCR-based genetic mapping delimited the EBS7 locus within an 850-kb region on chromosome 4 (Fig. 3A), which includes two candidate ERAD genes. One, At4g29330, encodes a homolog of the yeast Der1 known to be involved in ERAD (30–32), and the other, At4g29960, is coexpressed with many known/predicted ER proteins including three ERAD genes, EBS5 (At1g18260), EBS6 (At5g35080), and DERLIN-2.1 (At4g21810) (Fig. S3A) (33). We PCR-amplified and sequenced the two candidate genes from ebs7-1 bri1-9. Comparison of the resulting sequences with the published Arabidopsis wild-type sequences detected no mutation in At4g29330 but identified a G→A mutation in At4g29960 that causes a missense mutation of Ala131 to Thr (Fig. 3B). Its identity as the EBS7 gene was supported by sequencing At4g29960 in two allelic ebs7 mutants (ebs7-2 and ebs7-3) discovered in an independent genetic screen for bri1-5 suppressors (Fig. S2 B and C). In both mutants, a G→A mutation was detected that changes Gly74 to Glu in ebs7-2 and disrupts the correct splicing of the At4g29960 mRNA in ebs7-3 (Fig. 3B). Further support for At4g29660 being the EBS7 gene came from our complementation experiment showing that a genomic At4G29960 transgene rescued the morphological and biochemical phenotypes of the ebs7-1 mutation (Fig. 3 C–E and Fig. S2D).

Fig. 3.

EBS7 encodes an ER-localized membrane protein that is highly conserved in land plants. (A) Map-based cloning of EBS7. EBS7 was mapped to an ∼850-kb region on chromosome 4. Marker names are shown above the line, and recombinant numbers are shown below the line. The EBS7 gene structure is shown with bars denoting exons and lines indicating introns. Arrowheads show the positions of three ebs7 mutations. (B) The nucleotide changes and predicted molecular defects of the three ebs7 alleles. (C) Pictures of 4-wk-old wild-type, bri1-9, and two transgenic ebs7-1 bri1-9 mutant plants. (D) Immunoblot analysis of EBS7. Total proteins of 2-wk-old seedlings were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot using an anti-EBS7 antibody. (E) Immunoblot analysis of BRI1/bri1-9. (F) The confocal images of tobacco leaf epidermal cells transiently expressing GFP–EBS7 (Left), RFP–HDEL (Center), and superimposition of GFP and RFP signals (Right). (G) Immunoblot analysis of EBS7. Total (T), membrane (M), and soluble (S) proteins extracted from 2-wk-old seedlings were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with antibodies against EBS2, EBS5, and EBS7. In D and G, the asterisk indicates a nonspecific band serving as a loading control.

Fig. S3.

At4g29960 is coexpressed with at least three known/predicted ERAD genes and is ubiquitously expressed in Arabidopsis. (A) The coexpressed gene network around At4g29960, which was obtained from ATTEDII (atted.jp/) using At4g29960 (shaded yellow) as query. The red dots denote genes known/predicted to be involved in the Arabidopsis ERAD process, and black lines link strongly (thick lines) or weakly (thin lines) coexpressed genes. (B) Visualization of the expression profile of At4g29960 in different tissues of growing Arabidopsis plants, which was obtained from the Arabidopsis eFP browser web server (bar.utoronto.ca/efp_arabidopsis/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi) using At4g29960 as query. Reprinted with permission from ref. 34.

EBS7 Is a Plant-Specific Protein Conserved in Land Plants.

The EBS7 gene consists of five exons plus four introns (Fig. 3A), encodes a predicted polypeptide of 291 amino acids (Fig. S4A), and is ubiquitously expressed in Arabidopsis tissues/organs (Fig. S3B) (34). BLAST searches failed to identify any known protein motif in EBS7 or to discover EBS7 homologs in fungi or animals but did find EBS7 homologs in land plants, including Physcomitrella and Selaginella (Fig. S4). Sequence alignment between EBS7 and its plant homologs identified two major conserved regions, one in the middle and the other at the C terminus (Fig. S4A). The annotated At4g29960 protein was predicted to contain three transmembrane segments [aramemnon.botanik.uni-koeln.de/tm_sub.ep?GeneID=31811&ModelID=0 (35)], with the first two corresponding to the conserved middle region and the third overlapping with the conserved C terminus (Fig. S4A), suggesting that EBS7 is likely a membrane protein. It is interesting that Ala131, which is mutated to Thr in ebs7-1, is not conserved among the plant EBS7 homologs, whereas Gly74 mutated to Glu in ebs7-2 is absolutely conserved between EBS7 and its plant homologs (Fig. S4A). It is also worth mentioning that both the Ala131-to-Thr and Gly74-to-Glu mutations greatly reduce the abundance of ebs7 protein, likely because of potential misfolding of the mutant ebs7 proteins and their subsequent degradation (Fig. 3D and Fig. S2 C and D).

Fig. S4.

The sequence analyses of EBS7 homologs in land plants. (A) Sequence alignment of EBS7 and its representative plant homologs. Protein sequences of EBS7 (accession no. NP_567837), BdEBS7 (Bd: Brachypodium distachyon, XP_003577873), OsEBS7 (Os: Oryza sativa Japonica, NP_001053803), PtEBS7 (Pt: Populus trichocarpa, XP_002308117), GaEBS7 (Ga: Genlisea aurea, EPS72061), AtEBS7 (At: Amborella trichopoda, ERN12475), PsEBS7 (Ps: Picea sitchensis, ABR16454), and SmEBS7 (Sm: Selaginella moellendorffii, XP_002974885) were aligned using the ClustalW program (mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/portal.py). Aligned sequences were color-shaded at a BoxShade 3.31 server (mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/portal.py). Residues identical in more than six proteins are shaded red, and similar residues are shaded cyan. The positions of ebs7 mutations are indicated by green triangles, and the three predicted transmembrane segments are indicated by blue bars. (B) The phylogeny tree of plant EBS7 homologs. Names of plant species and accession numbers of the corresponding EBS7 homologs are as follows: Coffea canephora, CDP19559.1; Solanum lycopersicum, XP_004242818; Solanum tuberosum, XP_006361645; Mimulus guttatus, EYU18221.1; Mimulus guttatus, EYU38750.1; Genlisea aurea, EPS72061.1; Arabis alpina, KFK40291.1; Brassica napus, CDY03554.1; Brassica napus, CDY43545.1; Arabis alpina, KFK29555.1; Eutrema salsugineum, XP_006412781.1; Capsella rubella, XP_006284250; Arabidopsis lyrata, XP_002867378; Arabidopsis thaliana (EBS7), NP_567837.1; Cucumis melo, XP_008453570.1; Cucumis sativus, XP_004146332; Medicago truncatula, XP_003595067; Cicer arietinum, XP_004487987; Phaseolus vulgaris, ESW10771; Glycine max, XP_006597064; Glycine max, NP_001242739.1; Vitix vinifera, XP_002269262; Ricinus communis, XP_002527805; Jatropha curcas, KDP47202.1; Populus trichocarpa, XP_002324697.1; Populus trichocarpa, XP_002308117.2; Theobroma cacao, XP_007014411.1; Morus notabilis, EXB30996.1; Fragaria vesca subsp. vesca, XP_004296487.1; Malus domestica, XP_008354453; Prunus persica, EMJ12895; Prunus mume XP_008223885.1; Eucalyptus grandis, KCW78661.1; Citrus sinensis, KDO61891.1;Citrus clementina, XP_006453265; Setaria italica, XP_004976735; Zea mays, NP_001142664.1; Sorghum bicolor, XP_002447061; Zea mays, NP_001131686.1; Oryza brachyantha, XP_006653743; Oryza sativa Japonica Group, NP_001053803; Oryza sativa Indica Group, i-CAH66780; Aegilops tauschii, EMT30053; Fragaria vesca, XP_004296487; Triticum urartu, EMS50749; Brachypodium distachyon, XP_003577873; Phoenix dactylifera, XP_008781761.1; Amborella trichopoda, ERN12475; Picea sitchensis, ABR16454; Selaginella moellendorffii, XP_002974885; Physcomitrella patens, XP_001756855.1.

EBS7 Is an ER-Localized Membrane Protein That Accumulates Under ER Stress.

In line with the presence of three predicted transmembrane segments, EBS7/At4g29960 was identified previously as a putative PM protein by two independent studies (36, 37). Both studies used the aqueous two-phase partitioning method to enrich the PM fraction, which often is contaminated with organellar membrane proteins such as ER proteins. To determine where EBS7 localizes, we generated two GFP fusion constructs (with GFP fused at the N or C terminus of EBS7) driven by the constitutively active 35S promoter and transformed the two fusion constructs into ebs7-1 bri1-9. Only the GFP–EBS7, but not EBS7–GFP, transgene rescued the ebs7-1 mutation (Fig. S5A), indicating that GFP–EBS7 was physiologically functional. When GFP–EBS7 was transiently expressed in tobacco leaf epidermal cells, its subcellular localization pattern overlapped with that of a known ER maker, His-Asp-Glu-Leu–tagged red fluorescent protein (RFP–HDEL) (Fig. 3F) (38). Consistently, confocal microscopic analysis of the root tips of rescued GFP–EBS7/ebs7-1 bri1-9 transgenic seedlings revealed colocalization of GFP–EBS7 with another ER marker, ER Tracker Red dye (Fig. S5B). We also performed a subcellular fractionation experiment that separated soluble proteins from membrane proteins of wild-type Arabidopsis seedlings, which were analyzed further by immunoblot using antibodies against EBS2 [an ER luminal protein (12)], EBS5 [an ER membrane-anchored protein (21)], and EBS7. As shown in Fig. 3G, EBS2 was detected exclusively in the soluble fraction, but both EBS5 and EBS7 were detected only in the membrane fraction. Taken together, these experiments indicated that EBS7 is an ER membrane protein.

Fig. S5.

Analysis of stable Arabidopsis transgenic lines expressing GFP-tagged EBS7. (A) Pictures of representative transgenic ebs7-1 bri1-9 seedlings carrying GFP–EBS7, EBS7–GFP, or an empty vector, which were grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 100 μg/mL kanamycin. (B) Confocal images of root cells of a GFP–EBS7 transgenic line stained with 1 μM ER-Tracker Red dye and superimposition of the green and red fluorescent signals.

Consistent with its pattern of coexpression with genes of ER chaperones/folding enzymes (Fig. S3A), the EBS7 protein level was increased when the Arabidopsis seedlings were treated with tunicamycin (TM) (Fig. 4A), an N-glycan biosynthesis inhibitor widely used to induce ER stress (39). ER stresses can activate an ER stress-signaling pathway widely known as “unfolded protein response” (UPR) that increases expression of genes encoding ER chaperones, folding enzymes, and ERAD components to mitigate ER stress and maintain ER homeostasis (40, 41).

Fig. 4.

The ebs7-1 mutant exhibits constitutive UPR activation and is hypersensitive to ER stress. (A) Immunoblot analysis of ER proteins. Total proteins of 2-wk-old seedlings treated with or without 5 μg/mL TM were separated by SDS/PAGE and assayed by immunoblot with antibodies against binding immunoglobulin proteins (BiPs), protein disulfide isomerases (PDIs), calnexin/calreticulins (CNX/CRTs), EBS5, EBS6, and EBS7. Coomassie blue staining of RbcS on a duplicated gel serves as the loading control. (B) Pictures of 2-wk-old seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium containing 0 or 1 mM DTT. (C) Quantification analysis of seedling sensitivity to DTT. “Green”, “yellow”, or “dead” seedlings were counted, and the percentages of each type of seedlings were calculated and are shown in the bar graph. Error bars represent ± SD for three independent assays of ∼50 seedlings/each.

The ebs7-1 Mutation Causes the UPR and Results in Hypersensitivity to ER/Salt Stresses.

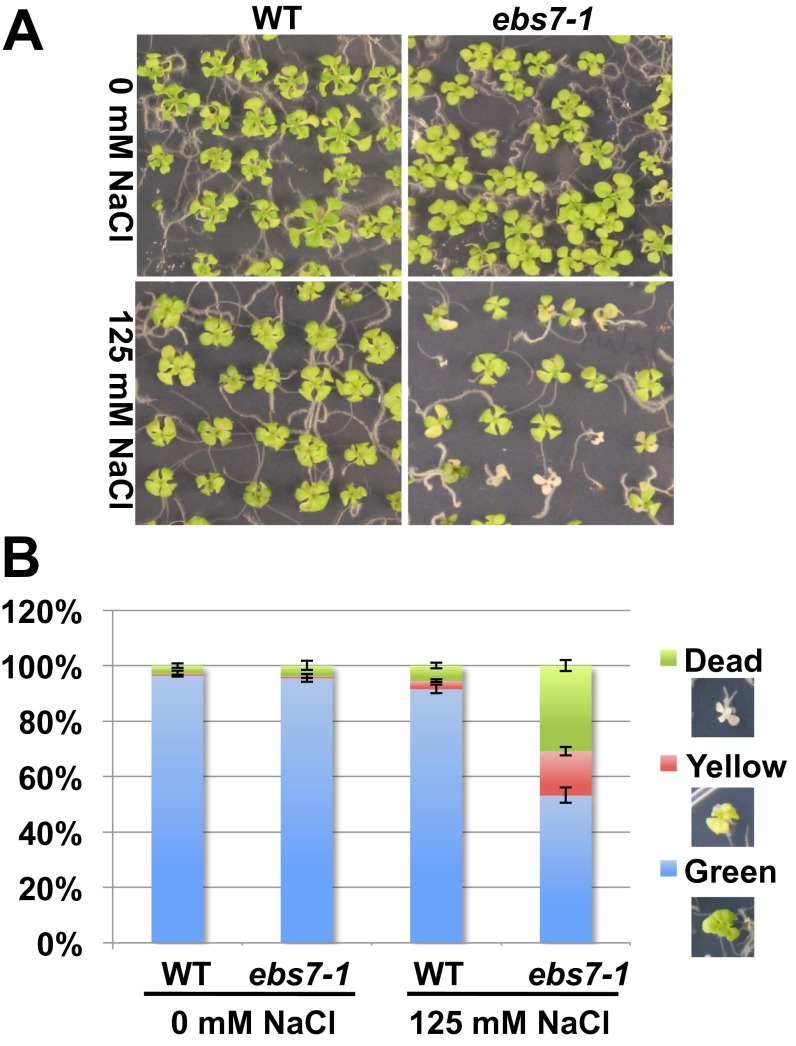

Interestingly, the levels of several known ER resident proteins were elevated in ebs7-1 even when ebs7-1 seedlings were grown on normal growth medium (Fig. 4A), indicating that the ebs7-1 mutation constitutively activated the UPR in the absence of TM. This finding is consistent with the crucial role of EBS7 in ERAD: Given the error-prone nature of protein folding, a compromised ERAD process would lead to the accumulation of many misfolded proteins in the ER, activating the UPR. Although ebs7-1 seedlings exhibited no obvious growth phenotype (Fig. 4B), they were hypersensitive to a low concentration of DTT (Fig. 4 B and C), a reducing agent known to induce ER stress by interfering with the formation of the disulfide bonds important for obtaining native protein conformations. Consistent with earlier studies of other Arabidopsis ERAD mutants (20, 22), ebs7 mutants also displayed increased salt sensitivity (Fig. S6).

Fig. S6.

The ebs7-1 mutation causes hypersensitivity to salt stress. (A) Pictures of 2-wk-old wild-type and ebs7-1 seedlings grown on 1/2 MS medium supplemented without (Upper) or with (Lower) 125 mM NaCl. (B) Quantification analysis of sensitivity to salt stress. Green, yellow, or dead seedlings were counted, and the percentages of each type of seedlings were calculated and are shown in the bar graph. Error bars represent ± SD for three independent assays of ∼50 seedlings/each.

The ebs7-1 Mutation Inhibits bri1-9 Ubiquitination.

Because an ER membrane-anchored E3 ligase is the central ERAD component (6), and our previous study revealed a redundant function of the two Arabidopsis homologs of the yeast Hrd1 in degrading bri1-9 (21), we examined if ebs7-1 affects bri1-9 ubiquitination using transgenic Arabidopsis lines expressing pBRI1:BRI1/bri1-9–GFP in wild-type or ebs7-1 seedlings. As shown in Fig. 5A, although bri1-9–GFP in the EBS7+ background was polyubiquitinated, no polyubiquitin signal was detected on bri1-9–GFP immunoprecipitated from the bri1-9–GFP ebs7-1 seedlings, despite its increased abundance. As expected, no anti-ubiquitin signal was detected on BRI1-GFP in the ebs7-1 or EBS7+ background. Thus, we concluded that ebs7-1 likely blocks the bri1-9 ubiquitination.

Fig. 5.

EBS7 interacts with AtHrd1a and affects its stability. (A) CoIP of bri1-9 and EBS5. Total proteins and anti-GFP immunoprecipitates obtained from wild-type or transgenic plants were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with antibodies against GFP, ubiquitin, or EBS5. (B) CoIP of EBS7, AtHrd1a, and EBS5. Total proteins and anti-GFP immunoprecipitates obtained from wild-type or transgenic Arabidopsis plants were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-GFP, anti-EBS7, and anti-EBS5 antibodies. (C and D) Immunoblot analysis of Hrd1a–GFP. Total proteins extracted from 2-wk-old seedlings treated with 180 μM CHX (C) or 80 μM MG132 (D) for varying durations were separated by SDS/PAGE and assayed by immunoblot with an anti-GFP antibody. Coomassie blue staining of RbcS on a duplicate gel serves as a loading control.

EBS7 Is Important for Maintaining the Stability of AtHrd1a.

Based on the current ERAD model (1, 16), an ERAD client is recognized and recruited by two recruitment factors, Hrd3/Sel1L and Yos9/OS9, and subsequently is delivered to the membrane-anchored E3 ligase Hrd1. To test if ebs7-1 affects the recruitment step of the bri1-9 ERAD process, we analyzed the interaction of bri1-9–GFP with EBS5, the Arabidopsis homolog of Hrd3/Sel1 (21). As shown in Fig. 5A, a strong interaction between bri1-9–GFP and EBS5 was detected in the ebs7-1 mutant by a coimmunoprecipitation (coIP) experiment. We also examined if ebs7-1 might affect the assembly of the AtHrd1a complex that includes the two recruitment factors. Fig. 5B shows that the ebs7-1 mutation has a little impact on the EBS5–AtHrd1a interaction. Taken together, these results suggest that ebs7-1 is unlikely to affect an ERAD step upstream of the bri1-9 ubiquitination.

We suspected that EBS7 might interact directly with AtHrd1. To test our hypothesis, we performed a coIP experiment using a transgenic Arabidopsis line expressing C-terminally GFP-tagged AtHrd1a, which functionally complemented an hrd1a hrd1b double mutant in a bri1-9 background (Fig. S7A). Fig. 5B shows that the coIP experiment that assayed the EBS5–AtHrd1a binding also revealed a strong AtHrd1a–EBS7 interaction, which was confirmed by a reciprocal coIP experiment with the same transgenic seedlings (Fig. S7B) and a yeast two-hybrid assay using truncated variants of EBS7 and AtHrd1a (Fig. S7 C and D).

Fig. S7.

Analysis of EBS7 interaction with Hrd1a and EBS5. (A) Pictures of 12-d-old wild-type seedlings, the bri1-9 single mutant, an hrd1a hrd1b bri1-9 triple mutant, and its transgenic line expressing a p35S:Hrd1a–GFP transgene. (B) CoIP of Hrd1a and EBS7. Total proteins and anti-EBS7 immunoprecipitates from wild-type or AtHrd1a–GFP–expressing transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with anti-EBS7 or anti-GFP antibodies. (C) Schematic diagram of the truncated C-Hrd1a and N-EBS7 fragments used for a yeast two-hybrid assay testing AtHrd1a-EBS7 interaction. The blue bars represent putative transmembrane segments, and the pink triangle denotes the RING domain of the AtHrd1a E3 ligase. (D) Yeast colonies coexpressing C-Hrd1a fused with the activation domain (AD) of the yeast GAL4 protein and the GAL4’s DNA-binding (BD) domain only, Gal4BD-fused C-Hrd1a, or Gal4BD-fused N-EBS7. (E) CoIP of EBS7 and EBS5. Total proteins and anti-EBS7 immunoprecipitates obtained from wild, ebs5-5, or ebs7-1 plants were separated by SDS/PAGE, transferred to a membrane, and analyzed by immunoblot with antibodies made against EBS5 or EBS7.

We hypothesized that EBS7 binds AtHrd1a to regulate its stability and/or activity. Because of the lack of an AtHrd1a antibody, it was impossible to compare the AtHrd1a levels in bri1-9 and ebs7-1 bri1-9 mutants directly. Instead, we used AtHrd1a–GFP transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings, which were treated with 180 μM CHX, to analyze if ebs7-1 reduces the stability of AtHrd1a. Fig. 5C shows that AtHrd1a was quite stable in wild-type seedlings but became unstable in ebs7-1 plants, suggesting that EBS7 plays an important role in maintaining the protein stability of the ER membrane-anchored E3 ligase. Interestingly, a short treatment of MG132, a known inhibitor of proteasome, greatly increased AtHrd1a abundance in ebs7-1 but had a marginal effect on that of the AtHrd1a–GFP EBS7+ transgenic line (Fig. 5D). The MG132 result not only confirmed the role of EBS7 in regulating the AtHrd1a stability but also suggested that AtHrd1a in ebs7-1 might be degraded via a proteasome-mediated pathway.

Discussion

EBS7 Is a Plant-Specific ER Membrane-Anchored Component of an Arabidopsis ERAD System.

Despite rapid progress in understanding the plant ERAD process, it remains unknown if plant ERAD involves a plant-specific component, because all previous studies identified homologs of known components of the yeast/mammalian ERAD pathways (see review in ref. 16). In this study, we show that EBS7 is a plant-specific component of the Arabidopsis ERAD machinery. First, all three ebs7 mutants were isolated in two independent genetic screens for potential ERAD mutants defective in degrading bri1-9 or bri1-5, and our subsequent biochemical experiments confirmed that ebs7 mutations prevented the degradation of two ER-retained mutant variants of BRI1 (Figs. 1 and 2). Our study showed that ebs7-1 also blocked ERAD of a misfolded conformer of an Arabidopsis immunity receptor, EFR (Fig. 2F). Second, multiple previous microarray experiments revealed that EBS7/At4g29960 is coexpressed with genes encoding ERAD components and other ER-localized chaperones/folding catalysts (Fig. S3A); this coexpression was the main reason for its being considered a prime candidate gene for map-based cloning. We also showed that EBS7 is an ER-localized membrane protein that accumulates in response to ER stress (Figs. 3F and 4A). Third, our biochemical assays demonstrated that EBS7 interacted with at least two known ERAD components, EBS5 and AtHrd1a (Fig. 5B and Fig. S7), and that ebs7-1 inhibited the ubiquitination of the bri1-9 protein (Fig. 5A). Fourth, in line with previous observations of other known Arabidopsis ERAD components (20, 22), we found that loss-of-function ebs7 mutations constitutively activated the UPR and led to increased sensitivity to ER/salt stresses (Fig. 4 and Fig. S6). Last, BLAST searches against protein databases failed to identify EBS7 homologs in fungi or animals but discovered highly similar proteins in land plants, including Selaginella and Physcomitrella (Fig. S4).

EBS7 Plays an Important Role in Regulating AtHrd1a Stability.

Although our data do not exclude the possibility that EBS7 is necessary for the ubiquitin ligase activity of AtHrd1a, our study strongly suggests that EBS7 regulates the stability of the AtHrd1a protein. Our CHX-chasing assay revealed that ebs7-1 greatly increased the degradation rate of AtHrd1a (Fig. 5C), and our MG132 assay indicated that a brief treatment with the proteasome inhibitor significantly increased the AtHrd1a abundance (Fig. 5D). It is well known that yeast and mammalian ERAD E3 ligases are regulated by self-/heterologous ubiquitination (42), and our observed EBS7–AtHrd1a interaction suggested that EBS7 binding could prevent the self-/heterologous ubiquitination activity and subsequent degradation of the Arabidopsis ERAD E3 ligase. Alternatively, EBS7 might be involved in the assembly of an AtHrd1a-containing ERAD complex because EBS7 also interacts with EBS5 (Fig. S7E), the Arabidopsis homolog of Hrd3/SEl1L, which functions as one of the two recruitment factors for a committed ERAD client. Although the ebs7-1 mutation had little effect on the EBS5–AtHrd1a interaction (Fig. 5B), it could interfere the binding of AtHrd1a with other components of the Arabidopsis ERAD machinery, including another ERAD client-recruitment factor, EBS6 (19, 20), an ER membrane-anchored E2, UBC32 (24), and/or one or more Arabidopsis homologs of the yeast Der1/mammalian Derlins. It also is possible that ebs7 mutations compromise the AtHrd1a oligomerization. It is well known that the ER-mediated protein quality-control system retains and degrades not only misfolded proteins, such as bri1-5, bri1-9, and misfolded EFR, but also improperly assembled polypeptides. An improperly assembled AtHrd1a thus could be degraded by an AtHrd1a-independent ERAD pathway. It is interesting that both the yeast Usa1 and mammalian HERP are known to interact directly with their corresponding ER membrane-anchored E3 ligases and are thought to regulate the stability and/or oligomerization of their interacting E3 ligases (43–45). Despite the absence of sequence homology with Usa1 and HERP, both of which carry an ubiquitin-like domain at the N terminus, EBS7 could be a functional homolog of Usa1/HERP. However, our complementation experiments revealed that EBS7 failed to complement a yeast Δusa1 mutant and that a HERP transgene driven by the strong 35S promoter was unable to rescue the ebs7-1 mutation (Fig. S8). We hypothesize that the biochemical mechanism by which EBS7 regulates the stability and/or oligomerization of the Arabidopsis Hrd1 homologs might be different from the mechanism by which Usa1/HERP regulate their interacting ERAD E3 ligases. Further investigation is needed to understand fully the biochemical function of this plant-specific component in regulating a highly conserved plant ERAD pathway.

Fig. S8.

EBS7 is not likely to be a functional homolog of the yeast Usa1 or the mammalian HERP. (A) Immunoblot analysis of the protein abundance of CPY* in the yeast BY4742 and Δusa1p strains carrying the indicated expression plasmids. Coomassie blue staining of an unknown major yeast protein on a duplicate gel serves as the loading control. (B) Pictures of two representative 4-wk-old soil-grown transgenic ebs7-1 bri1-9 plants carrying the empty vector (Left) or the p35S:HERP–GFP transgene (Right).

Materials and Methods

Details of map-based cloning of EBS7, plasmid construction, generation of transgenic plants, expression of fusion proteins in Escherichia coli, generation of antibodies, and immunoblot, membrane fractionation, and coIP experiments are given in SI Materials and Methods. Oligonucleotides used in this study are given in Table S1.

Table S1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence | Use |

| G3883 | CATCCATCAAACAAACTCC | SSLP |

| TGTTTCAGAGTAGCCAATTC | Ws-2 < Col-0 | |

| DHS1 | CAAGTGACCTGAAGAGTATCG | dCAPS (derived cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence) |

| AGAGAGAATGAGAAATGGAGG | DdeI cuts Col-0 PCR fragments | |

| 13978 | AAGTAAGAGTAACCGAGGCGATC | dCAPS |

| TAGGGAGGAGACAGAATCAGGGAA | EcoRI cuts Col-0 PCR fragment | |

| 15000 | ACAATACAGAAGTTGCATAACTGCA | dCAPS |

| AAACTATACCATGTGAAATACGGG | PstI cuts Col-0 PCR fragment | |

| 16546 | CAGATAAAAGAAATAGATCTTCCCACTA | dCAPS |

| TGTTGAAGGCTCTTGGTACACAG | SpeI cuts Ws-2 PCR fragment | |

| GFPN | TACGAGCTCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAACTTTTCA | Generation of the pCHF1–GFPN vector |

| GGGGTACCTTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATGT | ||

| GFPC | CGGGATCCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAGAAC | Generation of the pCHF1–GFPC vector |

| GACGTCGACTTATTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGC | ||

| gEBS7 | TGCGTCGACGGAGTTGTACCTGACTCGATC | Generation of an EBS7 genomic transgene |

| TCGGCAGCTTGTTTCTGAACC | ||

| GFPN–EBS7 | GAAGATCTATGACGGAAGAACCAGAGAAGGTG | Generation of an GFP–EBS7 fusion transgene |

| CATGTCGACCTACTCTATGTTGTGAAAACCAGGGA | ||

| EBS7–GFPC | GCTCTAGAGAAAATGACGGAAGAACCAG | Generation of an EBS7–GFP fusion construct |

| GAAGATCTTCTATGTTGTGAAAACCAGGGAG | ||

| EBS7–GST | TCGAATTCATGACGGAAGAACCAGAGAAGG | Generation of an expression fusion construct of EBS7-GST |

| TGCGTCGACTCACTGAAATCTCCTTTCCACAACATG | ||

| EBS7–MBP | TCGAATTCATGACGGAAGAACCAGAGAAGG | Generation of an expression fusion construct of EBS7-MBP |

| TGCGTCGACTCAAGGTAGCTGCTGCTGCTGACC | ||

| HERP–GFP | CGGGATCCATGGAGTCCGAGACCGAACCCG | Generation of an hsHERP–GFP transgene |

| CCGCTCGAGTCAGTTTGCGATGGCTGGGG | ||

| Hrd1a–GFP | GGGGTACCCATAGAAACACCGTTTCCTCCTC | Generation of an Hrd1a–GFP transgene |

| CGGGATCCCTCTGCTGCATCAGCAACCGAC | ||

| 352–Usa1 | ATGTCTGAATATCTAGCTCAGACGC | Generation of a Usa1 yeast expression construct |

| GCTCTAGATTAGTCTTCATCAGGAATGTAGAGATG | ||

| 352–EBS7 | ATGACGGAAGAACCAGAGAAGGT | Generation of an EBS7 yeast expression plasmid |

| GCTCTAGACTACTCTATGTTGTGAAAACCAGGGA | ||

| pGADT7–C-Hrd1a | CCGGAATTCCGGGAGCTCTACGAAACC | Generation of the yeast two-hybrid plasmid pGADT7–C-Hrd1a |

| GCGTGTCGACCTACTCTGCTGCATCAGCAAC | ||

| pGBKT7–N-EBS7 | CCGGAATTCATGACGGAAGAACCAGAG | Generation of the yeast two-hybrid plasmid pGBKT7–N-EBS7 |

| GCGTGTCGACCTACTGAAATCTCCTTTCCAC |

Underlined sequences indicate restriction sites used for subcloning PCR-amplified DNA fragments.

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions.

Most of the Arabidopsis wild-type, mutant, and transgenic plants used in the study are in the Columbia-0 (Col-0) ecotype, except for bri1-5, its two allelic ebs7 suppressors (ebs7-2 and ebs7-3), and a different bri1-9 mutant (used for mapping the EBS7 locus), which are all in the Wassilewskija-2 (Ws-2) ecotype. Methods of seed sterilization and plant growth conditions were described previously (46), and the root-growth inhibition assay on BL-containing medium was performed according to a previously described protocol (47).

Tobacco Transient Expression and Confocal Microscopic Analysis of EBS7–GFP Fusion Proteins.

The Agrobacterium strains carrying the p35S:EBS7–GFP or p35S:RFP–HDEL plasmid were mixed and coinfiltrated into leaves of 5-wk-old tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) plants by the agro-infiltration method (48). The subcellular localization patterns of EBS7–GFP and RFP–HDEL proteins were examined using a Leica confocal laser-scanning microscope (TCS SP5 DM6000B) and LAS AF software (Leica Microsystems). GFP and RFP were excited by using 488- and 543-nm laser lights, respectively.

SI Materials and Methods

Map-Based Cloning of EBS7.

The ebs7-1 bri1-9 mutant (Col-0) was crossed with bri1-9 (Ws-2) to obtain the F1 plants. F1 plants were self-fertilized to generate several F2 mapping populations. Genomic DNAs of ∼300 ebs7-1–like F2 plants were used for PCR-based mapping (see Table S1 for the major markers used for mapping) to locate the EBS7 locus within an 850-kb region on the middle of chromosome 4. To sequence candidate genes, genomic DNAs of four individual ebs7-1 bri1-9 plants were extracted, PCR-amplified, sequenced, and compared with the corresponding wild-type genes to detect SNPs.

Plasmid Construction and Generation of Transgenic Plants.

A 3.8-kb genomic fragment of At4g29960 was amplified from the genomic DNA of the wild-type Arabidopsis (Col-0) using the gEBS7 primer set (see Table S1 for primer sequences) and was cloned into pPZP222 to make the pPZP222-gEBS7 plasmid. To generate a p35S:GFP–EBS7 transgene, a 714-bp coding sequence of GFP was amplified from pBRI1:BRI1–GFP (49) using the GFPN primer set (Table S1) and was cloned into the pCHF1 vector (50) to create a pCHF1–GFPN plasmid. The resulting vector was used to generate the translational fusion construct of GFP–EBS7 with a 876-bp EBS7 cDNA fragment amplified from a cDNA preparation of the wild-type Arabidopsis (19) using the GFPN–EBS7 primer set (Table S1). A PCR-amplified 876-bp EBS7 cDNA fragment [using the EBS7–GFPC primer set (Table S1)] was used to replace the BRI1 coding sequence of pBRI1:bri1-9–GFP to generate pBRI1:EBS7–GFP. The p35S:AtHrd1a–GFP transgene was created by cloning a 1,479-bp AtHrd1a cDNA fragment amplified from the same Arabidopsis cDNA preparation using the Hrd1a–GFP primer set (Table S1) into the pCHF1:GFPC vector, which was created by cloning the 714-bp GFP-coding sequence of pBRI1:BRI1–GFP (49) amplified with the GFPC primer set (Table S1) into the pCHF1 vector (50). To generate the p35S:GFP–HERP plasmid, a 1,176-bp cDNA fragment of the human HERP was amplified from a human 293T cDNA library using the primer set HERP–GFP (Table S1) and was cloned into the pCHF1:GFPC vector. All these plasmids were fully sequenced to ensure there was no PCR-introduced error. The gEBS2, pBRI1:BRI1–GFP, pBRI1:bri1-9–GFP, and p35S:RFP–HDEL constructs were described previously (12, 13, 21). All transgenic constructs were mobilized into the Agrobacterium GV3101 strain, and the resulting Agrobacterium cells were used to transform the wild-type Arabidopsis or the ebs7-1 bri1-9 plants by the vacuum infiltration method (51) or to infect tobacco leaves by agroinfiltration (48).

Expression of Fusion Proteins in E. coli and Generation of Antibodies.

A 450-bp cDNA fragment encoding the 140-amino acid N-terminal fragment of EBS7 was cloned into pGEX-4T-1 (GE Healthcare) and pMAL-c2x (New England BioLabs). The resulting plasmids were transformed into BL21-competent cells (Novagen). The induction and purification of the GST-tagged EBS7 [using glutathione Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare)] or the maltose-binding protein (MBP)-fused EBS7 [on amylose resin (New England BioLabs)] were carried out according to the manufacturers’ recommended procedures. The purified GST–EBS7 was sent to Pacific Immunology (https//www.pacificimmunology.com) for custom antibody production, and the resulting antiserum was used for affinity-purifying the anti-EBS7 antibody using MBP–EBS7 immobilized on Aminolink Plus coupling resin (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s coupling/purification protocols.

Phylogeny Analysis of Plant EBS7 Homologs.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of EBS7 and its plant homologs was performed by the ClustalW program (52) at the Mobyle portal (mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/portal.py). The protdist and neighbor-joining programs of the Phylip package (evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html) were used to construct the phylogenetic tree, which was visualized using TreeDyn (www.phylogeny.fr/) (53).

Immunoblot, Membrane Fractionation, and CoIP Experiments.

Two-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings treated with or without BL (Chemiclones Inc.), CHX (Sigma), TM (Tocris), or MG132 (Sigma) were ground into fine powder in liquid N2, dissolved in 2× SDS buffer, boiled for 5 min, and centrifuged for 10 min. The resulting supernatants were incubated with or without 1,000 U Endo-Hf in 1× G5 buffer (New England BioLabs) for 1.5 h at 37 °C or were loaded directly onto 7% or 10% SDS/PAGE for separation. After transfer to PVDF membrane (Millipore), separated proteins were analyzed by immunoblot with antibodies against BES1 (54), BRI1 (55), BiP (at-95; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), maize-CRT (56), PDI (Rose Biotechnology Inc.), EBS5 (21), EBS6 (19), EBS7, or GFP (MNS-118P; Covance). For coIP experiments, 0.5 g of Arabidopsis seedlings were harvested, ground in liquid N2, and dissolved in the extraction buffer [50 mM Tris⋅Cl (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.4% (vol/vol) Triton X-100, a protease inhibitor mix including 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 1 μM pepstatin A, 0.5 mg/mL benzamidine hydrochloride, and a deubiquitinase inhibitor, 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide]. After filtration through 25-μm Miracloth (Calbiochem), samples were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants were incubated with an anti-GFP antibody (TP401; Torrey Pines Biolabs) and protein A-agarose beads (Invitrogen) for 8 h at 4 °C to precipitate GFP-tagged proteins. The immunoprecipitates were washed four times with the extraction buffer, boiled with 2× SDS buffer, separated by SDS/PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore), and analyzed by immunoblot with antibodies against GFP (MMS-118P; Covance), ubiquitin (P4D1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), EBS5 (21), or EBS7. For the cell fractionation experiment, 0.5 g of 2-wk-old Arabidopsis seedlings were ground in liquid N2, dissolved in homogenization buffer (the extraction buffer without Triton X-100), and centrifuged for 10 min at 8,000 × g at 4 °C. The supernatant (total proteins) was centrifuged further at 100,000 × g at 4 °C for 60 min to collect the supernatant (soluble fraction) and the pellet, which was dissolved in the extraction buffer as the membrane fraction. All three fractions were mixed with 2× SDS buffer, boiled for 5 min, separated by 10% SDS/PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblot.

Subcellular Localization of bri1-9–GFP and GFP–EBS7 in Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants.

The root tips of 3-d-old transgenic pBRI1:bri1-9–GFP/ebs7-1 and pBRI1:bri1-9–GFP/EBS7+seedlings were visualized using a laser confocal microscope (Leica SP8). To determine the subcellular localization of the GFP-tagged EBS7 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants, the root tips of 3-d-old seedlings of a phenotypically complemented p35S:GFP–EBS7/ebs7-1 transgenic line were stained with the Invitrogen’s ER-tracker Red dye (1 µM) and were examined microscopically using a laser confocal microscope (Leica SP8). To measure the intensities of GFP signals at the PM and inside the ER, digital images acquired by confocal microscopy were analyzed using ImageJ (imagej.nih.gov/ij/). Specifically, boundaries of the whole cell and the ER/cytosol of a total of 15 cells per figure were traced manually, and integrated GFP fluorescence densities within the outlined areas were quantified. The integrated GFP density at the PM was calculated subsequently by subtracting the integrated GFP density of the ER/cytosol from the integrated GFP density of the entire cell and was used to calculate the ratio of the GFP signals at the PM to the GFP signals inside the ER/cytosol.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay of the EBS7–Hrd1a Interaction.

The Clontech yeast two-hybrid system was used for testing the EBS7–Hrd1a interaction. The PCR-amplified DNA fragment corresponding to the N-terminal 142 amino acids of EBS7 (N-EBS7) was cloned into the pGBKT7 vector, and the DNA fragment encoding amino acids 247–492 of the Arabidopsis AtHrd1a (C-Hrd1a) was cloned into the pGADT7 vector (see Table S1 for the primer sequences used for amplifying the N-EBS7 and C-Hrd1a fragments). The two resulting constructs were fully sequenced to ensure no PCR-introduced error. Three pairs of plasmids, pGBKT7+pGADT7-C-Hrd1a, pGBKT7-C-Hrd1a+pGADT7-C-Hrd1a, and pGBKT7-N-EBS7+pGADT7-C-Hrd1a, were independently cotransformed into yeast cells. The yeast transformants were selected by growth on synthetic medium lacking leucine and tryptophan, and growing colonies were picked and spotted onto synthetic medium lacking leucine, tryptophan, and histidine to test the EBS7-Hrd1a interaction.

Yeast Complementation Assay.

The yeast wild-type strain BY4742 and a Δusa1 mutant strain carrying the pDN436 plasmid encoding a HA-tagged CPY* (an ER-retained mutant variant of the yeast vacuolar carboxypeptidase Y) were a gift from A. Chang, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI. The coding sequences of the yeast Usa1 (2.5 kb) and EBS7 (786 bp) were amplified from yeast and Arabidopsis using the primer sets 352-Usa1 and 352-EBS7, respectively, (Table S1) and were cloned into the pYEp352-ALG9p expression vector (17) to create pYEp352–Usa1 and pYEp352–EBS7 constructs, respectively. After full sequencing to ensure no PCR-introduced error, the two plasmids were transformed into the Δusa1 yeast cells using a previously reported fast transformation method (57). Yeast cultures of the midlog phase were treated with 100 μg/mL CHX for 0, 45, or 90 min and subsequently were collected by centrifugation. Collected yeast cells were resuspended in 1× yeast extraction buffer (0.3 M sorbitol, 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM Tris⋅Cl, pH 7.4), lysed by vortexing with glass beads for 5 min, and boiled for 10 min in 2× SDS sample buffer. After centrifugation supernatants were separated by 10% SDS/PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot with an anti-HA antibody (10A5; Invitrogen).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center at Ohio State University for supplying the T-DNA insertional mutant of AtHrd1a and AtHrd1b; F. Tax (University of Arizona) for seeds of bri1-5 (Ws-2) and bri1-9 (Ws-2); J. Chory (Salk Institute) for anti-BRI1 antibody; Y. Yin (Iowa State University) for anti-BES1 antibody; R. Boston (North Carolina State University) for anti-maize CRT antibody; T. Tzfira for the p35S:RFP–HDEL plasmid; and members of the J.L. laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported in part by Grant OVPRE-U032381 from the University of Michigan and Grant 2012CSP004 from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1511724112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ruggiano A, Foresti O, Carvalho P. Quality control: ER-associated degradation: Protein quality control and beyond. J Cell Biol. 2014;204(6):869–879. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vembar SS, Brodsky JL. One step at a time: Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(12):944–957. doi: 10.1038/nrm2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebert DN, Molinari M. Flagging and docking: Dual roles for N-glycans in protein quality control and cellular proteostasis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37(10):404–410. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denic V, Quan EM, Weissman JS. A luminal surveillance complex that selects misfolded glycoproteins for ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2006;126(2):349–359. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gauss R, Jarosch E, Sommer T, Hirsch C. A complex of Yos9p and the HRD ligase integrates endoplasmic reticulum quality control into the degradation machinery. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(8):849–854. doi: 10.1038/ncb1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kostova Z, Tsai YC, Weissman AM. Ubiquitin ligases, critical mediators of endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18(6):770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olzmann JA, Kopito RR, Christianson JC. The mammalian endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation system. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(9):a013185. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a013185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie W, Ng DT. ERAD substrate recognition in budding yeast. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21(5):533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagola K, Mehnert M, Jarosch E, Sommer T. Protein dislocation from the ER. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1808(3):925–936. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf DH, Stolz A. The Cdc48 machine in endoplasmic reticulum associated protein degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823(1):117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceriotti A, Roberts LM. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation in plant cells. In: Robinson DG, editor. The Plant Endoplasmic Reticulum. Springer; Berlin: 2006. pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin H, Hong Z, Su W, Li J. A plant-specific calreticulin is a key retention factor for a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(32):13612–13617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906144106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin H, Yan Z, Nam KH, Li J. Allele-specific suppression of a defective brassinosteroid receptor reveals a physiological role of UGGT in ER quality control. Mol Cell. 2007;26(6):821–830. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong Z, Jin H, Tzfira T, Li J. Multiple mechanism-mediated retention of a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20(12):3418–3429. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong Z, Li J. 2012. The protein quality control of plant receptor-like kinases in the endoplasmic reticulum. Receptor-Like Kinases in Plants: From Development to Defense. Signaling and Communication in Plants, eds. Tax F, Kemmerling B. (Springer, Berlin), Vol. 13, pp 275–307.

- 16.Liu Y, Li J. Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated protein quality control in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:162. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong Z, et al. Evolutionarily conserved glycan signal to degrade aberrant brassinosteroid receptors in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(28):11437–11442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119173109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong Z, et al. Mutations of an alpha1,6 mannosyltransferase inhibit endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of defective brassinosteroid receptors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21(12):3792–3802. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su W, Liu Y, Xia Y, Hong Z, Li J. The Arabidopsis homolog of the mammalian OS-9 protein plays a key role in the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of misfolded receptor-like kinases. Mol Plant. 2012;5(4):929–940. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hüttner S, Veit C, Schoberer J, Grass J, Strasser R. Unraveling the function of Arabidopsis thaliana OS9 in the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of glycoproteins. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;79(1-2):21–33. doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9891-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su W, Liu Y, Xia Y, Hong Z, Li J. Conserved endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation system to eliminate mutated receptor-like kinases in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(2):870–875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013251108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu L, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation is necessary for plant salt tolerance. Cell Res. 2011;21(6):957–969. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hüttner S, et al. Arabidopsis Class I α-Mannosidases MNS4 and MNS5 Are Involved in Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation of Misfolded Glycoproteins. Plant Cell. 2014;26(4):1712–1728. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.123216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui F, et al. Arabidopsis ubiquitin conjugase UBC32 is an ERAD component that functions in brassinosteroid-mediated salt stress tolerance. Plant Cell. 2012;24(1):233–244. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.093062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yin Y, et al. BES1 accumulates in the nucleus in response to brassinosteroids to regulate gene expression and promote stem elongation. Cell. 2002;109(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00721-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zipfel C, et al. Perception of the bacterial PAMP EF-Tu by the receptor EFR restricts Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Cell. 2006;125(4):749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, et al. Specific ER quality control components required for biogenesis of the plant innate immune receptor EFR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(37):15973–15978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905532106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saijo Y, et al. Receptor quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum for plant innate immunity. EMBO J. 2009;28(21):3439–3449. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saijo Y. ER quality control of immune receptors and regulators in plants. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12(6):716–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knop M, Finger A, Braun T, Hellmuth K, Wolf DH. Der1, a novel protein specifically required for endoplasmic reticulum degradation in yeast. EMBO J. 1996;15(4):753–763. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lilley BN, Ploegh HL. A membrane protein required for dislocation of misfolded proteins from the ER. Nature. 2004;429(6994):834–840. doi: 10.1038/nature02592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye Y, Shibata Y, Yun C, Ron D, Rapoport TA. A membrane protein complex mediates retro-translocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol. Nature. 2004;429(6994):841–847. doi: 10.1038/nature02656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Obayashi T, Hayashi S, Saeki M, Ohta H, Kinoshita K. ATTED-II provides coexpressed gene networks for Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D987–D991. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winter D, et al. An “Electronic Fluorescent Pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS One. 2007;2(8):e718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwacke R, et al. ARAMEMNON, a novel database for Arabidopsis integral membrane proteins. Plant Physiol. 2003;131(1):16–26. doi: 10.1104/pp.011577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitra SK, Walters BT, Clouse SD, Goshe MB. An efficient organic solvent based extraction method for the proteomic analysis of Arabidopsis plasma membranes. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(6):2752–2767. doi: 10.1021/pr801044y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benschop JJ, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics of early elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6(7):1198–1214. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600429-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu CJ, Dixon RA. Elicitor-induced association of isoflavone O-methyltransferase with endomembranes prevents the formation and 7-O-methylation of daidzein during isoflavonoid phytoalexin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2001;13(12):2643–2658. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elbein AD. The tunicamycins - useful tools for studies on glycoproteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1981;6(8):219–221. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hetz C. The unfolded protein response: Controlling cell fate decisions under ER stress and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(2):89–102. doi: 10.1038/nrm3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howell SH. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64:477–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weissman AM, Shabek N, Ciechanover A. The predator becomes the prey: Regulating the ubiquitin system by ubiquitylation and degradation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(9):605–620. doi: 10.1038/nrm3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carroll SM, Hampton RY. Usa1p is required for optimal function and regulation of the Hrd1p endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation ubiquitin ligase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(8):5146–5156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim I, Li Y, Muniz P, Rao H. Usa1 protein facilitates substrate ubiquitylation through two separate domains. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leitman J, et al. Herp coordinates compartmentalization and recruitment of HRD1 and misfolded proteins for ERAD. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(7):1050–1060. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-06-0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, Nam KH, Vafeados D, Chory J. BIN2, a new brassinosteroid-insensitive locus in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127(1):14–22. doi: 10.1104/pp.127.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clouse SD, Langford M, McMorris TC. A brassinosteroid-insensitive mutant in Arabidopsis thaliana exhibits multiple defects in growth and development. Plant Physiol. 1996;111(3):671–678. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Voinnet O, Rivas S, Mestre P, Baulcombe D. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 2003;33(5):949–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedrichsen DM, Joazeiro CA, Li J, Hunter T, Chory J. Brassinosteroid-insensitive-1 is a ubiquitously expressed leucine-rich repeat receptor serine/threonine kinase. Plant Physiol. 2000;123(4):1247–1256. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.4.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fankhauser C, et al. PKS1, a substrate phosphorylated by phytochrome that modulates light signaling in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;284(5419):1539–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bechtold N, Pelletier G. In planta Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants by vacuum infiltration. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;82:259–266. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-391-0:259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chevenet F, Brun C, Bañuls AL, Jacq B, Christen R. TreeDyn: Towards dynamic graphics and annotations for analyses of trees. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:439. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mora-García S, et al. Nuclear protein phosphatases with Kelch-repeat domains modulate the response to brassinosteroids in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2004;18(4):448–460. doi: 10.1101/gad.1174204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang ZY, Seto H, Fujioka S, Yoshida S, Chory J. BRI1 is a critical component of a plasma-membrane receptor for plant steroids. Nature. 2001;410(6826):380–383. doi: 10.1038/35066597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Persson S, et al. Phylogenetic analyses and expression studies reveal two distinct groups of calreticulin isoforms in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 2003;133(3):1385–1396. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gietz RD, Woods RA. Transformation of yeast by lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/polyethylene glycol method. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]