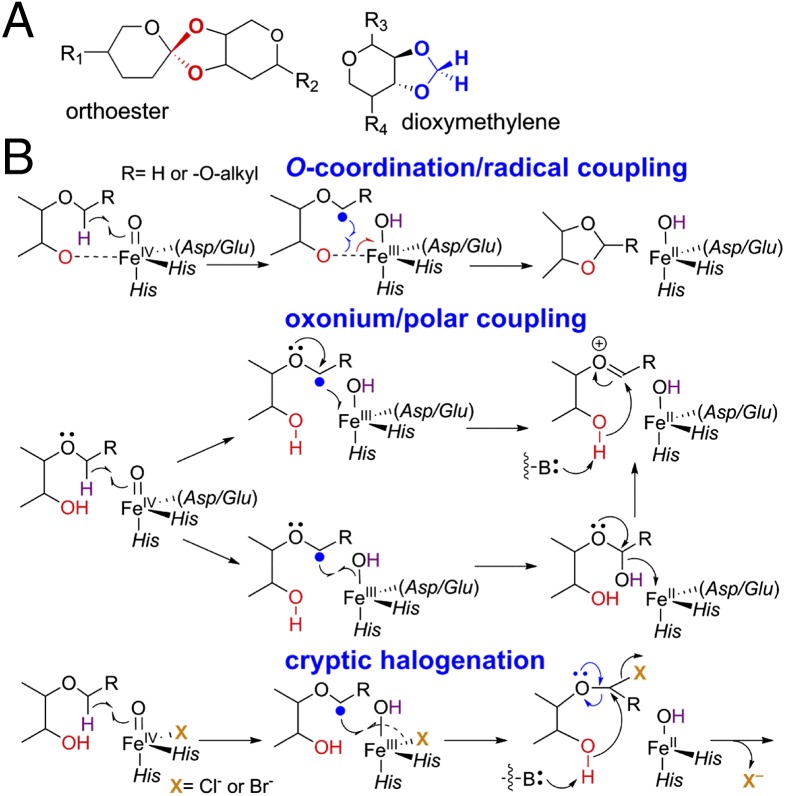

Bacteria, fungi, and plants produce an arsenal of complex biomolecules through which they interact and compete with neighbor organisms (1). The machinery that builds these molecules is replete with iron(II)- and 2-(oxo)glutarate-dependent (Fe/2OG) oxygenases, enzymes that catalyze hydroxylation, halogenation, desaturation, ring-closure, ring-expansion, and stereoinversion reactions on pathways to important natural-product drugs (2). In PNAS, McCulloch, et al. provide evidence for two new reaction types by members of this versatile enzyme class (3). The reactions would explain how two unusual structures (Fig. 1A), orthoester (Fig. 1A, red) and dioxymethylene (Fig. 1A, blue) oxacycles, are installed into the oligosaccharide antibiotics known as orthosomycins (4). Reminiscent of previously demonstrated “oxacyclization” reactions in biosyntheses of such important drugs as clavulanic acid and scopolamine (2), these reactions add to the impressive repertoire of transformations by Fe/2OG enzymes and extend the intriguing mechanistic conundrum posed by the known oxacyclizations.

Fig. 1.

Oxacycles in orthosomycins (A) and possible mechanisms for their formation (B).

Well-studied members of the Fe/2OG class use the conserved nonheme Fe(II) cofactor to coordinate reduction of dioxygen (O2) with oxidative decarboxylation of 2OG to CO2 and succinate (2). This process generates a potently oxidizing Fe(IV) intermediate, with an oxo (formally O2–) ligand derived from O2. The most impressive capabilities of the Fe(IV)=O (ferryl) moiety, including—most likely—the oxacyclizations, derive from its ability to abstract hydrogen as a radical (H•) from inert aliphatic carbon centers. The manifold of different reactions arises from the different fates of the resulting carbon-centered radical, which forms along with the Fe(III)-OH form of the conserved cofactor. In the hydroxylases, the carbon radical bites back upon the hydroxo ligand, abstracting it as a radical (HO•) in the classic “oxygen rebound.” In the halogenases, the radical instead attacks a halogen coordinated cis to the oxygen ligand, an alternative radical transfer. The mechanisms of the desaturations, ring expansions, and ring closures are less well understood but, for the last of these reactions, a halogenase-like mechanism has been considered. In this mechanism, the ferryl intermediate abstracts H• from the carbon to be coupled to oxygen (Fig. 1B). The carbon radical then attacks the oxygen to close the ring (Fig. 1B, Top). For this mechanism to be viable, the oxygen would, seemingly, have to be coordinated to the iron cofactor (Fig. 1B, dashed line), so that the other electron formally in the dative Fe–O bond could flow into the metal (Fig. 1B, red arrow) as the formal alkoxyl radical couples to the carbon radical (Fig. 1B, blue arrows). Indeed, cofactor coordination by the substrate heteroatom (sulfur or oxygen) has been shown for isopenicillin N synthase (5) and (S)-2-hydroxypropylphosphonic acid epoxidase (6), two 2OG-independent cyclases. For the 2OG-dependent cyclizations, the requirement for O-coordination challenges the feasibility of the radical-coupling mechanism (2). The reason is that the cosubstrate (2OG) occupies two coordination sites with its C1 carboxylate and C2 carbonyl oxygens. With the three protein ligands of the conserved 2-histidine-1-carboxylate “facial triad,” there remains just one open site, needed for addition of O2 to form the ferryl complex. An obvious coordination site is not available for the substrate oxygen. The halogenases overcome this site-insufficiency problem with an abbreviated ligand set. They retain the two histidine ligands of the facial triad but, crucially, lack the carboxylate ligand, the Asp or Glu residue that would normally provide it having been replaced in the sequence by an alanine or glycine residue (Fig. 2, Top Right) (7). This effective ligand deletion opens a site for halide coordination, enabling carbon–halogen bond formation by radical coupling. In principle, this adaptation could also work for the oxacyclizations, but most of the enzymes previously shown to mediate such reactions have the conserved carboxylate residue. To this existing mechanistic puzzle, the McCulloch, et al. (3) study adds important pieces.

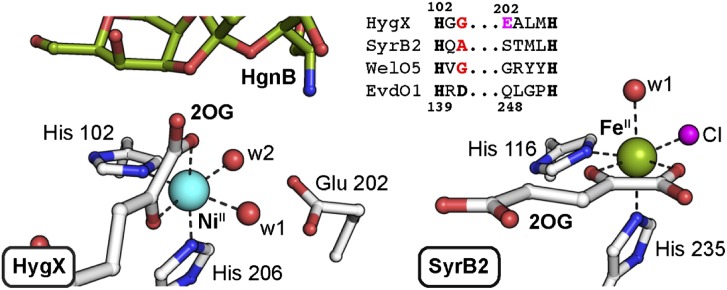

Fig. 2.

Comparison of HygX (putative oxacyclization enzyme) (Left, PDB ID code 4XCB) and SyrB2 halogenase (Right, PDB ID code 2FCT) structures showing a conserved ligand deletion pattern (Top).

The authors solved 3D structures of four proteins encoded within gene clusters specifying biosynthetic machinery for the orthosomycins, avilamycin, everninomicin, and hygromycin B (HgnB) (3). The proteins had previously been assigned as likely Fe/2OG oxygenases and the enzymes from the avilamycin cluster implicated in installation of the novel oxacycles (8), but no supporting biochemical evidence had been presented. McCulloch, et al.’s (3) structure of the HygX protein with its putative orthosomycin product, HgnB, bound in the active site (Fig. 2, Left) provides the first such evidence. Observation of the orthoester moiety <6.0 Å from the metal ion in the HygX•Ni(II)•2OG•HgnB complex, with an oxygen-linked carbon directed toward the metal, strongly suggests that HygX is indeed an oxacyclase.

Although fundamental aspects of the reaction—for example, which carbon of the substrate donates H• to the ferryl complex to form the radical and which initially bears the oxygen that is incorporated into the ring—remain unresolved, the unexpected structural similarity to Fe/2OG halogenases (Fig. 2, Bottom Right), including deletion of the carboxylate ligand (Fig. 2, Top Right), suggests that HygX might use a radical-coupling ring-closure mechanism (Fig. 1B, Top). In principle, the oxygen of the substrate could coordinate at the site of the missing carboxylate to enable this mechanism. This simplest solution seems unlikely from the HygX structure, but there is another slightly more complex, and potentially more general, possibility. There have been a number of recent hints that the locations of the iron ligands, especially the 2OG carboxylate and the oxo/hydroxo ligand of the key intermediate states, can be different from expectations based on the structures of the reactant complexes and the simplest mechanistic assumptions. For example, structural evidence suggests that the O2 surrogate, NO•, adds to the Fe(II) cofactor of clavaminate synthase at the site occupied in the reactant complex by the 2OG carboxylate, which relocates to the site most directly apposed to the carbon involved in ring formation (9). Similarly, recent spectroscopic and computational studies on SyrB2 concluded that the oxo ligand of the cis-haloferryl intermediate resides essentially in the site occupied by the 2OG carboxylate in the crystal structure of the SyrB2•Fe(II)•2OG•Cl complex (10) and that NO• may occupy this site in the ferric-nitrosyl complex (11). Intriguingly, the crystal structure of HygX shows that the C1 carboxylate is already located where it is suggested to move upon O2/NO• addition in clavaminate synthase and SyrB2. Irrespective of the presence or absence of the facial triad carboxylate ligand, loss of the 2OG carboxylate from the site most proximal to the substrate could potentially permit its O-coordination there in the ferryl state to enable a halogenase-like ring closure. The similarities of the HygX primary and tertiary structures to those of the halogenases and the apparent analogy between the halogenases and the oxacyclase, clavaminate synthase, with respect to ligand (re)locations (9–11) make this mechanism appealing.

A polar C–O coupling mechanism could obviate direct substrate coordination (Fig. 1B, Middle and Bottom) (2). Unlike previously documented oxacyclizations, the substrates in the orthoester- and dioxymethylene-installing reactions would already have a lone-pair–bearing oxygen atom bonded to the carbon undergoing C–O coupling, potentially enabling neighboring group facilitation of a polar mechanism. After generation of the carbon-centered radical by the ferryl complex, electron transfer to the Fe(III)–OH intermediate would form an oxonium species (Fig. 1B, Middle and Top), which could undergo attack by the oxygen nucleophile to close the new ring. Alternatively, the canonical “oxygen rebound” could be followed by elimination of hydroxide (Fig. 1B, Middle and Bottom), enabled by the neighboring oxygen and possibly the Fe(II) cofactor (as shown), to form the same oxonium intermediate. A more complex polar ring-closure mechanism, not explicitly addressed by McCulloch, et al. (3)—but suggested by the halogenase-like deletion of the facial-triad carboxylate ligand in HygX—would involve transient halogenation of the substrate. Installation of the halide-leaving group would permit nucleophilic attack of the substrate oxygen upon the halogenated carbon, either directly or, again, with anchimeric assistance via an oxonium intermediate (Fig. 1B, Bottom). The recent discovery of WelO5, a carrier-protein–independent halogenase in the welwitindolinone biosynthetic pathway (12), and the previously demonstrated formation of the cyclopropyl ring of coronamic acid by this “cryptic-halogenation” strategy (13), provide precedent.

More work is needed to map the pathway by which the highly oxygenated orthoester and dioxymethylene oxacycles are installed into the orthosomycins. Gold-standard proof of the posited oxacyclase activity—the demonstration of the reaction in vitro or identification of an acyclic precursor in cultures of knockout mutants—has not yet been achieved. Preparation of the elaborate substrates for the hypothetical new reactions could be exceedingly challenging. Insight into the mechanisms of the more well-established examples, which are still poorly understood, thus remains an important goal that could help narrow the focus of future studies on the orthosomycin-associated reactions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 11547 in issue 37 of volume 112.

References

- 1.Clardy J, Walsh C. Lessons from natural molecules. Nature. 2004;432(7019):829–837. doi: 10.1038/nature03194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bollinger JM, Jr, et al. Mechanisms of 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenases: The hydroxylation paradigm and beyond. In: Hausinger RP, Schofield CJ, editors. 2-Oxoglutarate-Dependent Oxygenases. Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK; 2015. pp. 95–122. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCulloch KM, et al. Oxidative cyclizations in orthosomycin biosynthesis expand the known chemistry of an oxygenase superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(37):11547–11552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500964112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright DE. The orthosomycins, a new family of antibiotics. Tetrahedron. 1979;35(10):1207–1237. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roach PL, et al. Structure of isopenicillin N synthase complexed with substrate and the mechanism of penicillin formation. Nature. 1997;387(6635):827–830. doi: 10.1038/42990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yun D, et al. Structural basis of regiospecificity of a mononuclear iron enzyme in antibiotic fosfomycin biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(29):11262–11269. doi: 10.1021/ja2025728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blasiak LC, Vaillancourt FH, Walsh CT, Drennan CL. Crystal structure of the non-haem iron halogenase SyrB2 in syringomycin biosynthesis. Nature. 2006;440(7082):368–371. doi: 10.1038/nature04544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weitnauer G, et al. Biosynthesis of the orthosomycin antibiotic avilamycin A: Deductions from the molecular analysis of the avi biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü57 and production of new antibiotics. Chem Biol. 2001;8(6):569–581. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Z, et al. Crystal structure of a clavaminate synthase-Fe(II)-2-oxoglutarate-substrate-NO complex: Evidence for metal centered rearrangements. FEBS Lett. 2002;517(1-3):7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong SD, et al. Elucidation of the Fe(IV)=O intermediate in the catalytic cycle of the halogenase SyrB2. Nature. 2013;499(7458):320–323. doi: 10.1038/nature12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinie RJ, et al. Experimental correlation of substrate position with reaction outcome in the aliphatic halogenase, SyrB2. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(21):6912–6919. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillwig ML, Liu X. A new family of iron-dependent halogenases acts on freestanding substrates. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(11):921–923. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaillancourt FH, Yeh E, Vosburg DA, O’Connor SE, Walsh CT. Cryptic chlorination by a non-haem iron enzyme during cyclopropyl amino acid biosynthesis. Nature. 2005;436(7054):1191–1194. doi: 10.1038/nature03797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]