Significance

Clonal expansion of antigen-specific B cells during an immune response is necessary for effective antibody production. B cells must integrate signals from their clonally restricted B-cell antigen receptor (BCR) and from nonclonal coreceptors that provide contextual cues to the nature of the antigen. How this is accomplished is unclear. We found that B cells require expression of the BCR for mitogenic responses triggered by coreceptors that recognize innate or T-cell-derived signals. The signaling pathway used by the BCR to license coreceptor-induced proliferation is similar to the previously described BCR-dependent survival signal and, thus, couples B-cell survival and mitogenic responses in an unexpected manner that may have implications for B-cell lymphomagenesis.

Keywords: BCR, B-cell proliferation, PI-3K, GSK3β, Foxo1

Abstract

B cells respond to antigens by engagement of their B-cell antigen receptor (BCR) and of coreceptors through which signals from helper T cells or pathogen-associated molecular patterns are delivered. We show that the proliferative response of B cells to the latter stimuli is controlled by BCR-dependent activation of phosphoinositidyl 3-kinase (PI-3K) signaling. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β and Foxo1 are two PI-3K-regulated targets that play important roles, but to different extents, depending on the specific mitogen. These results suggest a model for integrating signals from the innate and the adaptive immune systems in the control of the B-cell immune response.

Expression of a functional B-cell antigen receptor (BCR) is of central importance to nearly every aspect of B-cell biology. During early development, B-lineage cells assemble clonally restricted Ig heavy and light chains that are able to recognize a diverse and unpredictable universe of antigens. The proper assembly and expression of a BCR is a prerequisite for entry into the naive compartment. Furthermore, naive resting B cells remain dependent on the expression of a correctly assembled BCR. If this is prevented by IgH chain ablation or Igα truncation, the cells rapidly undergo apoptosis. This has been interpreted to reflect a BCR-dependent “tonic” survival signal, which has recently been shown to involve phosphoinositidyl 3-kinase (PI-3K) activity and subsequent inactivation of the Foxo1 transcription factor (1–3).

As a consequence of the large, clonally restricted repertoire generated during development, only a small number of newly generated B cells entering the peripheral mature compartment express a BCR that is able to bind a given antigen. During the early stages of an immune response, antigen-specific B cells proliferate extensively and increase the number of cells that can respond appropriately. The magnitude, duration, and quality of the B-cell response is guided by signals from coreceptors expressed by B cells such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and CD40, which provide information to the B cell about the context of the antigen in T-cell-independent and T-cell-dependent responses (4, 5). Given that the raison d’être of B cells is an antigen-specific response, including the production of antibodies, a central role for the BCR in regulating B-cell responses to innate or T-cell-derived signals seems likely. Indeed, early experiments addressing the in vitro response of mouse B cells to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) have suggested cooperation of LPS stimulation and BCR engagement in the proliferative B-cell response under certain conditions (6, 7). More recent work has uncovered a synergy between TLR and BCR in the control of class-switch recombination in activated B cells (8), and the role of the BCR in the delivery of DNA- or RNA-associated autoantigens to endosomal TLRs in autoimmunity is well established (9). How B cells integrate signals from the BCR and from coreceptors responding to mitogenic stimuli in the induction of the proliferative response is unclear, however.

Results and Discussion

Generation of Resting BCR-Negative B Cells.

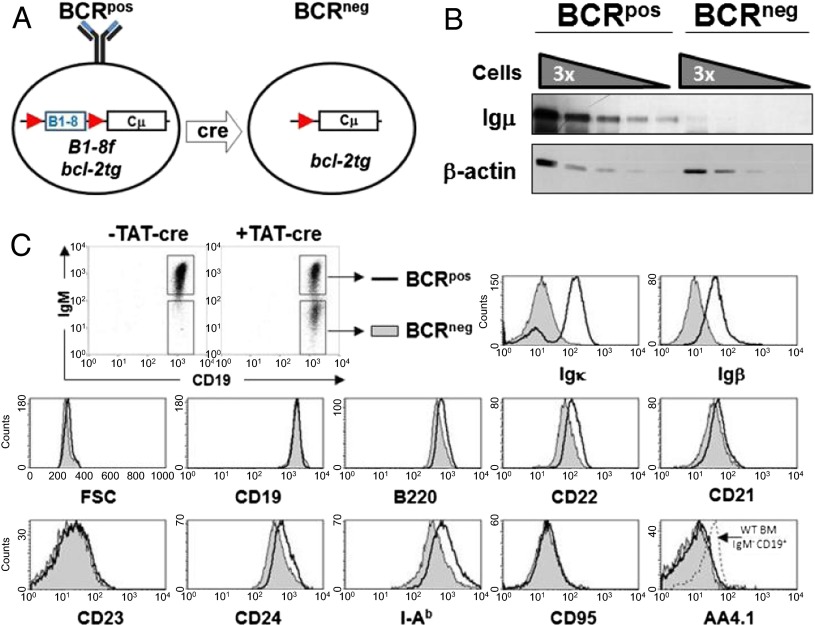

We generated resting B cells that lack expression of the BCR by transducing splenic B cells from bcl-2tg mice that express a loxP-flanked pre-rearranged variable domain targeted into the Igh locus (B1-8f) (2) with cell-permeable Cre recombinase, TAT-Cre (10). The transduced cells remained alive throughout the culture because of the ectopic expression of Bcl-2 and lost BCR expression by day 3 in culture with an efficiency of 30–50%, allowing simultaneous analysis of B cells that either express or lack the BCR (BCRpos and BCRneg B cells, respectively; Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis of sorted BCRpos and BCRneg B cells confirmed the loss of IgH chain expression in the latter (Fig. 1B). The proportion of BCRpos and BCRneg B cells remained constant for at least 2 wk, suggesting the two classes of cells survive equally well in vitro (Fig. S1). Although mature BCRneg cells are slightly smaller than their BCRpos counterparts and down-regulate some mature B-cell markers (e.g., MHC class II and CD22), they largely maintain the surface phenotype of resting, mature B cells (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

In vitro generation of BCRneg B cells. (A) Schematic showing Cre-mediated deletion of the loxP-flanked B1-8 allele and subsequent loss of BCR expression. (B) Splenic B cells from B1-8f/+, bcl-2tg mice were treated with recombinant TAT-Cre for 45 min, cultured for 9 d, and sorted by FACS to >98% purity based on IgM expression (data are representative of two biological replicates). Serial dilutions of whole-cell lysates starting at 300,000 cell equivalents were analyzed for Igμ and β-actin expression by Western blotting. (C) Splenic B cells from B1-8f/+, bcl-2tg mice were transduced with TAT-Cre for 45 min, cultured for 5 d in medium, and stained for CD19, IgM, and the indicated surface markers (data are representative of three biological replicates). BCRpos cells (open histograms) and BCRneg cells (closed histograms) were gated as shown.

Fig. S1.

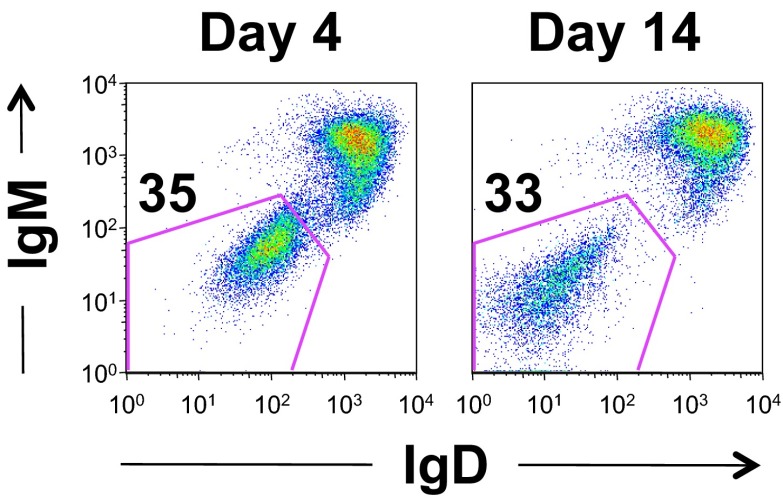

Expression of Bcl-2 rescues survival of BCRneg B cells in vitro. Purified splenic B cells were transduced with TAT-Cre for 45 min and cultured in vitro. After 4 or 14 d, cells were analyzed for a change in the proportion of ToPro3−, CD19+ B cells that lost expression of IgM and IgD. Data are representative of three biological replicates.

BCR Expression Is Necessary for the Mitogenic Response of B Cells.

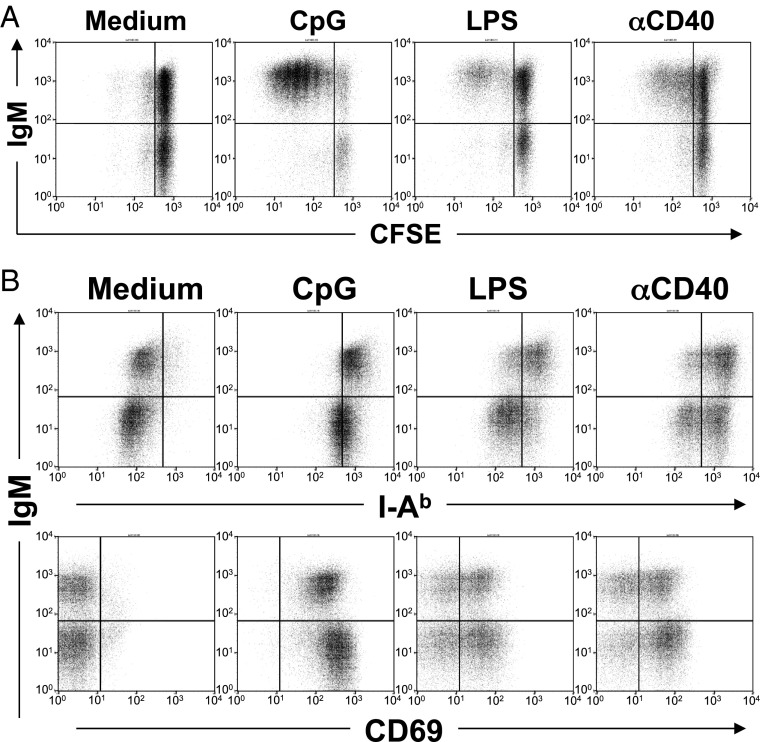

B cells express receptors such as TLR-9, TLR-4, and CD40 that induce activation and proliferation when triggered by natural ligands or agonist antibodies (11–13). We tested the proliferative response of BCRpos and BCRneg B cells to CpG DNA, LPS, or anti-CD40 and found that, in contrast to BCRpos B cells, BCRneg B cells did not proliferate in response to any of these stimuli (Fig. 2A). This defect is not an artifact of protein transduction because bcl-2tg BCRneg B cells generated by a tamoxifen-inducible Cre (14) or in vivo with a mature B-cell-specific Cre-transgene (CD21-Cre) (1) showed the same proliferation defect (Fig. S2). BCRneg B cells are not completely refractory to the mitogenic stimuli, as they activate normal NF-κB DNA binding activity in response to CpG (Fig. S3) and up-regulate CD69 and MHC class II when stimulated with CpG DNA, LPS, or anti-CD40 (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data show that mature B cells that have lost expression of the BCR are responsive to innate stimuli but are unable to proliferate.

Fig. 2.

Expression of the BCR is necessary for B-cell proliferation. BCRpos and BCRneg B cells were generated by TAT-Cre transduction of B cells from B1-8f/+, bcl-2tg mice. After 3 d in culture, cells were either (A) labeled with CFSE and stimulated for 3–4 d (data are representative of five biological replicates) or (B) stimulated for 24 h with the indicated mitogen and analyzed by FACS (data are representative of two biological replicates). Live cells were gated as ToPro3−, CD19+.

Fig. S2.

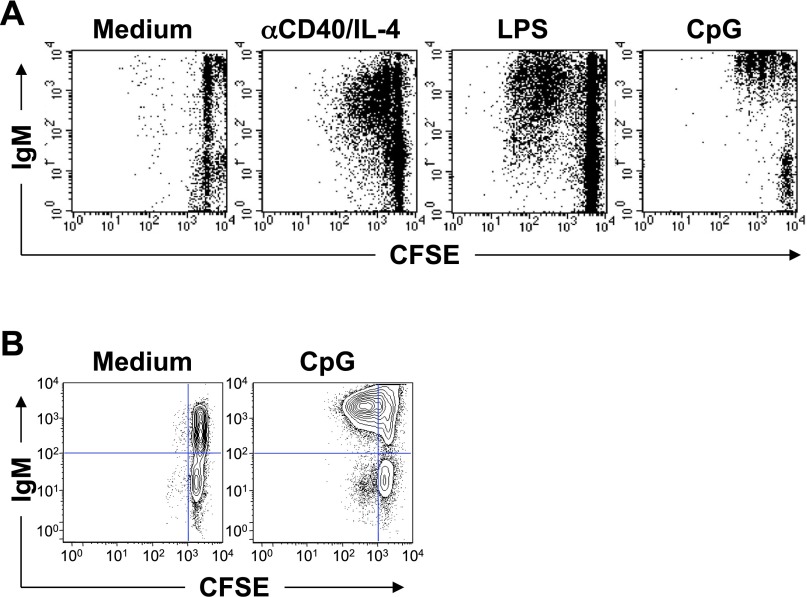

Defective proliferation of BCRneg B cells. (A) B cells from B1-8f/+, CreED-30, bcl-2tg mice were purified and treated with 4-OH-tamoxifen for 7 d before CFSE labeling and stimulation with the indicated mitogen for 3 d. Data are representative of three biological replicates. (B) Ex vivo isolated B cells from B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, bcl-2tg mice were labeled with CFSE and cultured in medium or with CpG for 3 d. ToPro3−, CD19+ cells are shown. Data are representative of two biological replicates.

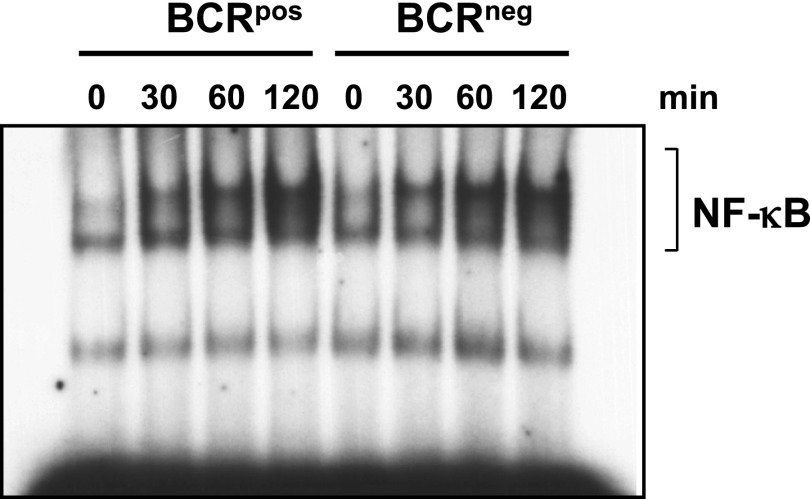

Fig. S3.

Stimulation with CpG induces normal NF-κB DNA-binding activity in BCRneg B cells. BCRpos and BCRneg B cells from B1-8f/+, bcl-2tg mice were cultured overnight in 1% FCS-containing medium and stimulated for the indicated times with CpG. Nuclear lysates were used for EMSA. The data presented here were biologically replicated once, using the 0- and 120-min times.

BCR Expression Licenses B-Cell Proliferation Through PI-3K Activation.

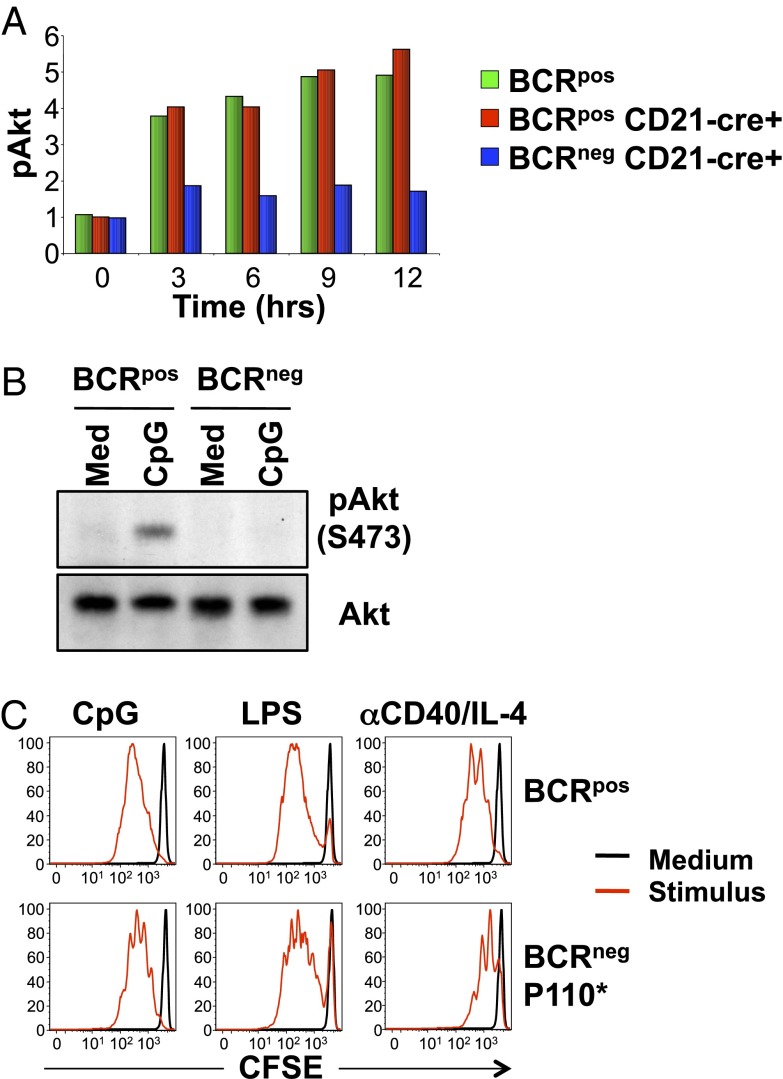

Previous studies demonstrated that constitutive, low-level signaling, a so-called tonic signal, which is dependent on an intact BCR, is necessary for mature B-cell survival (1, 2) and is mediated by the PI-3K/Akt/Foxo1 signaling pathway (3). The requirement of BCR expression for mitogenic responses of B cells to innate stimuli raised the possibility that the same tonic signal may also regulate B-cell proliferation. BCRneg B cells generated in vivo with a mature B-cell-specific Cre-transgene (i.e., CD21-Cre) (1) were used to study Akt status in vivo. Indeed, although intracellular staining for phospho-Akt (Ser473) of CpG-treated BCRpos B cells showed prolonged activation of the PI-3K pathway, induced Akt phosphorylation was not seen in BCRneg B cells under these conditions (Fig. 3A). This was confirmed by Western blot analysis of sorted BCRpos and BCRneg B cells cultured with or without CpG-containing medium for 2 h (Fig. 3B). We conclude that expression of the BCR as mediated by the IgH chain is required for mitogen-induced activation of the PI-3K pathway in response to CpG stimulation. To further test the role of BCR-dependent PI-3K signaling in regulating mitogen-induced proliferation of B cells, we isolated BCRneg B cells from B1-8f, CD21-Cre mice that also carried a transgene for an active PI-3K molecule that was induced by Cre activity (B1-8f, CD21-Cre, P110*) (3). Expression of Cre in mature B cells simultaneously ablates expression of the BCR and induces expression of constitutively active PI-3K, which substitutes for the BCR-dependent survival signal (3). Similar to control BCRpos B cells, BCRneg B cells expressing constitutively active PI-3K proliferated in response to all the stimuli (Fig. 3C), showing that reconstitution of the PI-3K pathway in BCRneg B cells licenses mitogenic responses to innate stimuli.

Fig. 3.

Defective activation of PI-3K in BCRneg B cells. (A) Splenic B cells from B1-8f/JHT, bcl-2tg or B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, bcl-2tg mice were stimulated with CpG for the indicated times and stained for CD19 and IgM and intracellular phospho-Akt (Ser473). BCRpos (green) cells were gated from B1-8f/JHT, bcl-2tg cells, whereas Cre+ BCRpos (red) or Cre+ BCRneg (blue) B cells were gated from B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, bcl-2tg cells. Normalized mean fluorescence intensity values for phospho-Akt (Ser473) are shown. Data represent three biological replicates. (B) BCRpos and BCRneg B cells were sorted from B1-8f/JHT, bcl-2tg splenic B cells 5 d after transduction with TAT-Cre, placed in culture overnight, and stimulated with CpG for 2 h. Equal amounts of cytoplasmic lysates were blotted for phospho-Akt (Ser473) and Akt. Data are representative of two biological replicates. (C) Splenic BCRpos and GFP+ BCRneg B cells were sorted from Rag2Δ/Δ, cγ−/− mice that had been reconstituted with fetal liver from B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, P110* mice, labeled with CFSE and cultured for 3 d in medium (black) or medium plus the indicated stimulus (red). Data are representative of three biological replicates.

Inactivation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β Is Necessary for the Proliferative Mitogenic Response of BCRneg B Cells to CpG.

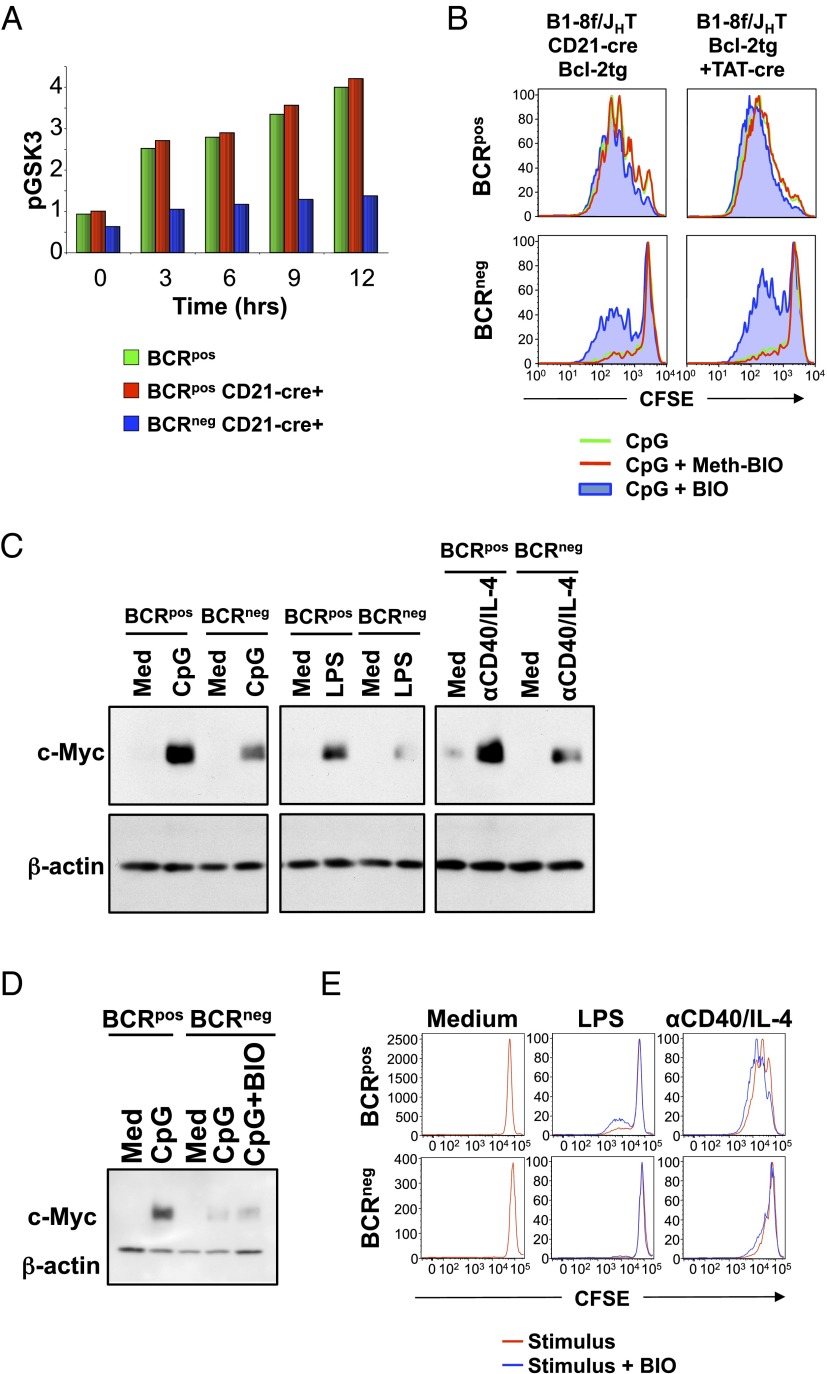

Next, we investigated the BCR-dependent signaling pathways downstream of PI-3K as required for mitogenic responses of B cells. PI-3K/Akt activates several downstream signaling pathways including pathways using glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and Foxo1. GSK3β is a constitutively active serine/threonine kinase that inhibits proliferation by phosphorylating and targeting for degradation proteins that are necessary for mitosis, including c-Myc (15) and d-type cyclins (16). Mitogenic signals activate the PI-3K/Akt pathway, leading to phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK3β (17), and thereby allowing accumulation of cell cycle-regulated proteins. Consistent with defective Akt phosphorylation in BCRneg B cells, the levels of phospho-GSK3β remained low in BCRneg B cells, in contrast to BCRpos B cells, after treatment with CpG (Fig. 4A), suggesting that GSK3β remained active in BCRneg B cells. To directly assess whether GSK3β activity prevents the proliferation of mitogen-treated BCRneg B cells, we added the GSK3β inhibitor (2′Z,3′E)-6-bromo-indirubin-3′-oxime (BIO) (18) to CpG-stimulated cultures and found that inhibition of GSK3β partially restores the ability of bcl-2tg BCRneg B cells to proliferate in response to CpG (Fig. 4B). We also found that CpG-induced c-Myc protein levels were much lower in BCRneg B cells than those seen in BCRpos B cells treated in a similar manner (Fig. 4C). Similar results were seen when LPS or anti-CD40/IL-4 were used as mitogens (Fig. 4C). In contrast, mitogen-induced c-Myc mRNA levels were nearly identical between BCRpos and BCRneg B cells stimulated with CpG (Fig. S4), suggesting that active GSK3β was destabilizing c-Myc protein in BCRneg B cells (15). Unfortunately, pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β activity using BIO, which partially restores proliferation in response to CpG (Fig. 4B), did not substantially restore mitogen-induced c-Myc protein expression in BCRneg B cells (Fig. 4D). Therefore, we conclude that the decreased levels of c-Myc induction in BCRneg B cells, although of potential interest, do not explain the defective proliferation of B cells that have lost expression of their BCR. Furthermore, inhibition of GSK3β did not rescue proliferation of BCRneg B cells in response to LPS or anti-CD40/IL-4 treatment (Fig. 4E), suggesting that BCR-dependent PI-3K activation regulates additional signaling pathways required for mitogenic responses, depending on the stimulus.

Fig. 4.

GSK3β activity prevents the proliferation of CpG-treated BCRneg B cells. (A) Splenic B cells from B1-8f/JHT, bcl-2tg or B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, bcl-2tg mice were stimulated with CpG for the indicated times and stained for CD19 and IgM and intracellular phospho-GSK3α/β (S21/9). BCRpos (green) cells were gated from B1-8f/JHT, bcl-2tg cells, whereas Cre+ BCRpos (red) or Cre+ BCRneg (blue) B cells were gated from B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, bcl-2tg cells. Normalized mean fluorescence interval values for phospho-GSK3α/β (S21/9) are shown. Data represent three biological replicates. (B) B cells from B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, bcl-2tg mice or TAT-Cre-transduced B cells from B1-8f/JHT, bcl-2tg mice were CFSE-labeled and stimulated for 3 d with CpG alone (green) or with Meth-BIO (inactive control inhibitor, red) or BIO (GSK3 inhibitor, blue). Cells were gated on ToPro3−, CD19+, and IgM+ or IgM−. Data are representative of three biological replicates. (C) Splenic B cells from B1-8f/+, bcl-2tg mice were TAT-Cre-transduced and cultured for 3 d. Purified BCRpos and BCRneg B cells were placed in culture overnight and stimulated with CpG, LPS, or anti-CD40/IL-4 for 6 h. Equal amounts of protein from whole-cell lysates were used for Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Data are representative of three biological replicates. (D) Sorted BCRpos and BCRneg B cells from B1-8f/+, CD21-Cre, bcl-2tg mice were cultured in medium, CpG, or CpG and BIO for 6 h. Lysates were analyzed by Western blot for c-Myc and β-actin levels. Data are representative of three biological replicates. (E) Splenic BCRpos and BCRneg B cells from B1-8f/+, CD21-Cre, bcl-2tg mice were sorted, labeled with CFSE, and cultured in media or with LPS or anti-CD40/IL-4 alone (red) or with BIO (blue). Data are representative of three biological replicates.

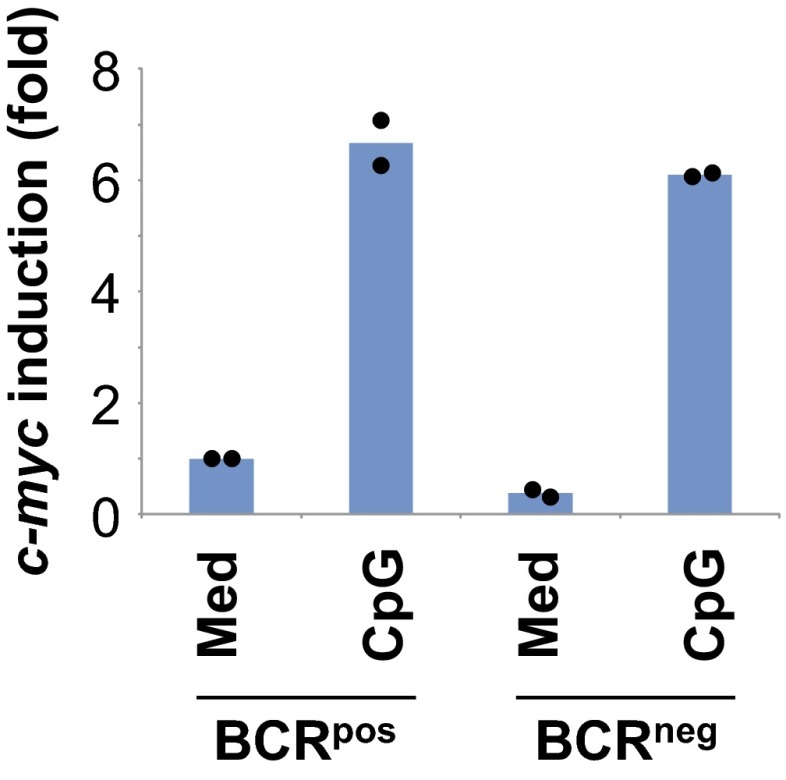

Fig. S4.

Normal induction of c-myc transcription in CpG-stimulated BCRneg B cells. Sorted BCRpos and BCRneg B cells generated by TAT-Cre transduction from B1-8f/+, bcl-2tg mice were stimulated for 3 h with medium or CpG. cDNA from purified RNA was used for quantitative RT-PCR analysis of c-myc and hprt expression. Data for two biologically independent experiments (average of technical duplicates shown for each biologically independent experiment) represent fold-change of c-myc expression relative to BCRpos B cells cultured in medium.

Foxo1 and GSK3β Regulate Innate Stimuli-Induced Mitogenic Responses Downstream of the BCR.

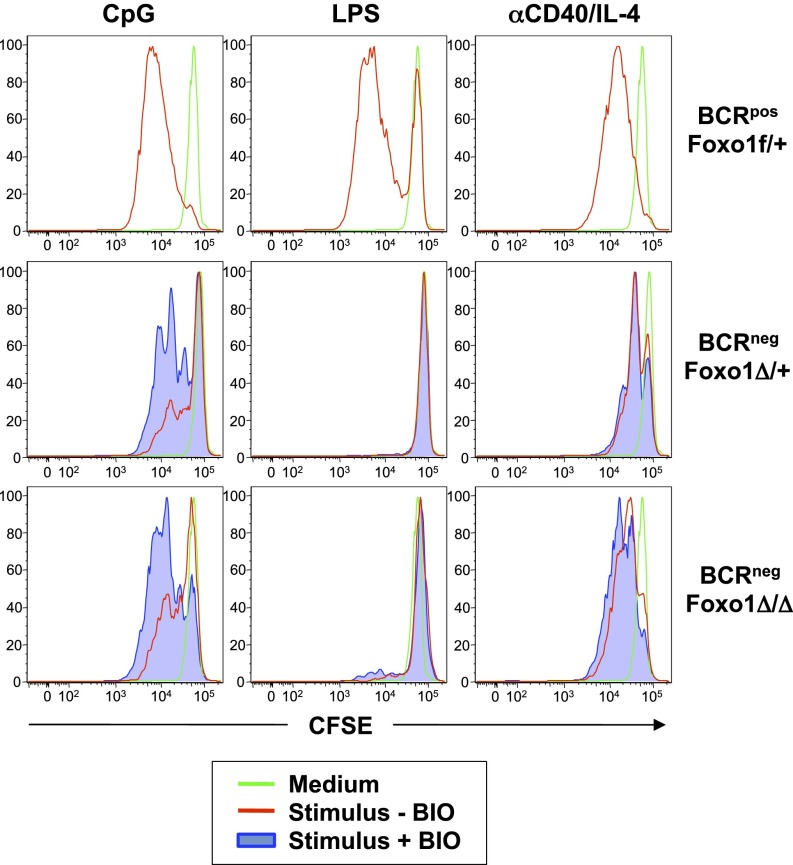

Inactivation of the transcription factor Foxo1 by BCR-dependent PI-3K/Akt activation is necessary for mature B-cell survival (3). The complete loss of Foxo1 rescues the survival of BCRneg B cells as efficiently as expression of active PI-3K, whereas loss of one Foxo1 allele is sufficient for a partial rescue of BCRneg B cells (3). Because Foxo1 remains active in BCRneg B cells (3) and can inhibit proliferation by up-regulating antiproliferative genes (19, 20), we tested the effect of Foxo1 ablation on mitogen-treated BCRneg B cells. BCRneg B cells that were either heterozygous or homozygous for a Foxo1-null allele were sorted, and their proliferative responses in the absence or presence of BIO to inhibit GSK3β were compared with mitogen-stimulated BCRpos cells (Fig. 5). Although the complete or partial loss of Foxo1 had only minimal effects on the proliferative response of BCRneg B cells to CpG, the combination of Foxo1 deletion and inhibition of GSK3β rescued the proliferation of BCRneg B cells in response to CpG to a level comparable to that observed by CpG-stimulated BCRpos B cells. In contrast, although heterozygous deletion of Foxo1 was sufficient for some anti-CD40/IL-4-treated BCRneg B cells to undergo at least one cell division, homozygous deletion of Foxo1 allowed near-complete rescue of BCRneg proliferation to anti-CD40/IL-4. In both cases, inhibition of GSK3β had little additional effect, suggesting that different mitogens require PI-3K to activate different signaling pathways for proliferation in the absence of BCR expression (Fig. 5). To further illustrate this point, BCRneg B cells on a Foxo1-null background in the presence of a GSK3β inhibitor remained unable to proliferate in response to LPS treatment (Fig. 5), suggesting that other or additional pathways downstream of PI-3K/Akt that regulate cell proliferation are involved.

Fig. 5.

Foxo1 deletion plus GSK3β inhibition rescues proliferation in CpG-treated BCRneg B cells. Splenic B cells were sorted, labeled with CFSE, and cultured either in medium (green) or with the indicated stimuli, with (blue) or without (red) the GSK3β inhibitor BIO. BCRpos, Foxo1f/+ and BCRneg Foxo1Δ/+ cells were sorted from B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, Foxo1f/+ mice, whereas BCRneg, Foxo1Δ/Δ cells were sorted from B1-8f/JHT, CD21-Cre, Foxo1f/f mice. Data are representative of three biological replicates.

Our experimental model is based on previous evidence that the BCR expressed by resting, mature B cells provides tonic survival signals to the cells (1, 2). The mechanism by which such signals are initiated is controversial, but may involve low-affinity interactions of the BCR with environmental antigens, akin to the positive selection of T cells by self-MHC. It is also possible, however, that loss of the BCR induces a danger signal in the cells from which they can be relieved by PI-3K pathway activation. By extending the analysis to the control of B-cell proliferation, the present data provide the elements of a molecular mechanism by which the BCR controls the proliferative expansion of B cells on the engagement of invariant, “innate” receptors. Such a crosstalk between these two classes of receptors reflects the physiological requirement of integrating, in any meaningful antibody response, input from the BCR regarding specific antigen recognition and information about the nature and context of the immunizing antigen, with the latter being provided to the cells by innate receptors such as TLRs recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns presented by microbes and the CD40 coreceptor triggered by T helper cells. The requirement of this regulatory principle is particularly obvious in the case of the somatic antibody mutants generated in the germinal center reaction, whose expansion through T-cell-derived and innate signals should strictly depend on newly acquired BCR specificities or BCR expression in the first place.

Although receptor-proximal signaling events in B cells differ among TLRs and CD40, these receptors share common downstream signaling pathways such as the PI-3K, MAPK, and NF-κB pathways (21, 22). This is supported by the similarity of gene expression profiles of primary B cells stimulated with distinct mitogenic agonists (23). The BCR appeared to specifically control PI-3K signaling in the cells, in that a key PI-3K target, Akt, was not phosphorylated in BCRneg cells on CpG stimulation (Fig. 3B), and expression of active PI-3K rescued mitogenic responses in the absence of the BCR (Fig. 3C). The BCR is apparently involved in this process in mitogen-activated B cells, conceivably by controlling the levels, activity, or localization of inhibitors of the PI-3K pathway. This scenario is supported by results showing that mature B cells undergoing Cre-mediated BCR deletion in vivo can be rescued from apoptosis by the expression of constitutively active PI-3K, as well as by the ablation of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), a lipid phosphatase that directly opposes PI-3K activity (24). Downstream of PI-3K activation, the signaling pathways diverge depending on the specific mitogen. Inactivation of Foxo1 is important for proliferation in response to anti-CD40/IL-4 stimulation, whereas inactivation of GSK3β plays a greater role in the mitogenic response to CpG. Interestingly, inactivation of both GSK3β and Foxo1 are not sufficient for LPS-induced proliferation, suggesting that additional BCR-dependent signaling pathways are activated by PI-3K and are necessary for TLR4-mediated proliferation of B cells. The present results indicate that, in addition to its role in the control of B-cell survival, BCR modulation of PI-3K signaling licenses the induction of clonal expansion of B cells by mitogens acting on innate receptors expressed by the cells, a process of crucial importance in the antibody response. In this scenario, BCR engagement by self-antigen or cognate antigen as well as cross-reactivity with mitogens (8) may well play a modulating role. Quite fittingly, the work of Pone et al. has identified an interplay between BCR and TLR signaling in the control of class-switch recombination in the activated B cells. This was mediated by NF-κB signals downstream of both receptors, which, significantly, depended on PI-3K activity in the case of the BCR (8).

The integration of signals delivered by distinct cellular receptors is an obvious requirement for any cellular response in multicellular organisms. An example is the outside-in signaling of integrins bound to extracellular matrix proteins, which mediate the proliferation of adherent epithelial cells in response to growth factors (25). Notably, the PI-3K pathway plays a role in this context as well, and also provides integrin-activated prosurvival signals to the adherent cells (26, 27). The interplay between the antigen receptor and innate immune receptors, which we have described here for B lymphocytes, may thus be just a variation of an ancient principle of receptor crosstalk in higher cells. It will be interesting to see whether this crosstalk also plays a role in the homeostasis of memory cells and to which extent and by what means the BCR licenses the proliferative expansion of B-cell lymphomas (28).

Materials and Methods

Mouse Strains.

B1-8f (2), JHT (29), bcl-2tg (30), CD21-Cre (1), rosa26-stopf-P110* (3), and CreED-30 (14) mice were housed and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. All mouse protocols were approved by Harvard University and the Immune Disease Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Cell Culture and TAT-Cre Transduction.

TAT-Cre (also known as His-TAT-NLS-Cre or HTNC, expression plasmid available from Addgene) was produced as described (10). Purified B cells were washed three times in serum-free, animal-defined component-free medium (HyClone), prewarmed to 37 °C, and transduced with 50 μg/mL TAT-Cre in the presence of 50 μg/mL polymyxin B sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) at a density of 5 × 106/mL for 45 min at 37 °C. Cells were then washed in complete medium [DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FCS (Biowhittacker), 10 mM Hepes, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1× penicillin/streptomycin, 1× nonessential amino acids (Cellgro), and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol] and cultured at 37 °C for 3–5 d at 2 × 106/mL in complete medium. Mock-transduced cells were treated identically except that TAT-Cre was omitted. B cells were labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE), as indicated, by washing two times in PBS, prewarming for 10 min at 37 °C, and incubating with titrated amounts of CFSE for 10 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed in complete medium and stimulated with 1 μg/mL anti-CD40 (1C10; eBioscience), 20 μg/mL ultrapure LPS (InvivoGen), or 645 ng/mL CpG (ODN1826; InvivoGen) at 2 × 105/mL in complete medium for 3–4 d. The GSK3 inhibitor BIO or the inactive control Meth-BIO (Calbiochem) were added at a concentration of 0.2 μM, as indicated.

FACS.

Single-cell suspensions of ex vivo splenocytes or cultured B cells were stained with antibodies to IgM (goat Fab; Jackson ImmunoResearch), IgD (1.3–5), Igκ (R33-18.10), Igβ (HM79), CD19 (1D3), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD22 (CY34), CD21 (7G6), CD23 (B3B4), CD24 (M1/69), CD95 (Jo2), CD93 (AA4.1), I-Ab (AF6-120), or CD69 (H1.2F3). Dead cells were excluded by addition of ToPro3 (Invitrogen). For intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized with Perm/Fix and Perm/Wash solutions (BD Bioscience) according to manufacturer’s instructions, stained with anti-phospho-Akt (S473; Cell Signaling) or anti-phospho-GSK3α/β (37F11; Cell Signaling), and detected with anti-rabbit-FITC. Data were collected on a FACSCalibur (BD Bioscience) and analyzed with CellQuest (BD Bioscience) or FlowJo (TreeStar) software.

Cell Separation.

Red blood cells were lysed by hypotonic shock from splenocyte suspensions. B cells were purified by CD43 depletion using magnetic-activated cell separation (MACS; Miltenyi). For some experiments, BCRneg B cells were isolated by MACS depletion of IgM+ B cells from TAT-Cre-transduced cultures using biotinylated anti-IgM (331-12) and streptavidin-beads (Miltenyi). Purity was >98%, as determined by IgD staining. Alternatively, B cells were stained with Fab anti-IgM and anti-B220 before FACS sorting on an Aria2 or FACSVantage (BD Bioscience).

Immunoblot Analysis.

Whole-cell lysates were prepared in lysis buffer [40 mM Tris at pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 1× EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche), 1 mM PMSF, 5 mM NaF, 0.5 μM, 1 mM Na3VO4]. The protein concentration was determined by detergent-compatible protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). The membranes were immunoblotted, as indicated, with phospho-Akt (S473), Akt (Cell Signaling), c-Myc (Epitomics), β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), or biotinylated goat Fab anti-mouse IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch).

NF-κB EMSA.

Splenic B cells from B1-8f/JHT, bcl-2tg mice were TAT-Cre-transduced and placed in culture for 3 d. Purified BCRpos and BCRneg B cells were then cultured overnight in 1% FCS-containing medium before the addition of CpG for the indicated amounts of time. Cells were lysed in buffer A (5 mM Hepes at pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors) to prepare cytosolic extracts and nuclei. Nuclear extracts were subsequently prepared using buffer C [20 mM Hepes at pH 7.9, 25% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.5 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, and protease inhibitors]. Nuclear extracts were incubated with competitor DNA (pdIdC; Sigma) and a 32P labeled-κB consensus probe (Promega). Protein–DNA complexes were then resolved by electrophoresis on a nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

RNA was purified using mirVana RNA isolation kit (Ambion) and subjected to cDNA synthesis, using random hexamer primers (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was performed using c-myc- and hprt-specific primers on a StepOne Plus (Applied Biosystems) machine. Primers used were: c-MycF1, 5′-gagcccctagtgctgcatgag-3′; c-MycR1, 5′-ttgcctcttctccacagacacc-3′; HPRTF1, 5′-ctataagttctttgctgacctgctggattaca-3′; HPRTR1, 5′-ccagttaaagttgagagatcatctccaccaataact-3′.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefano Casola, Marc Schmidt-Supprian, Dinis P. Calado, Jane Seagal, Sergei B. Koralov, and Michael Reth for helpful discussions. We thank Joanne L. Viney for critically reading the finished manuscript. We are grateful to Junrong Xia, Dvora Ghitza, Anthony Monti, Alex Pellerin, and Jackie Grundy for technical support. We thank Riikka Lauhkonen-Seitz for administrative assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI057947 and AI054636. K.R. is supported by an Advanced Grant from the European Research Council (ERC-2010-AdG_20100317 Grant 268921). A.F. is supported by a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions Individual Fellowship from the European Commission (H2020-MSCA-IF-2014_ST Grant 660883).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1516428112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Kraus M, Alimzhanov MB, Rajewsky N, Rajewsky K. Survival of resting mature B lymphocytes depends on BCR signaling via the Igalpha/β heterodimer. Cell. 2004;117(6):787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lam KP, Kühn R, Rajewsky K. In vivo ablation of surface immunoglobulin on mature B cells by inducible gene targeting results in rapid cell death. Cell. 1997;90(6):1073–1083. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srinivasan L, et al. PI3 kinase signals BCR-dependent mature B cell survival. Cell. 2009;139(3):573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Control of B-cell responses by Toll-like receptors. Nature. 2005;438(7066):364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature04267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medzhitov R. Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 2007;449(7164):819–826. doi: 10.1038/nature06246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson J, Bullock WW, Melchers F. Inhibition of mitogenic stimulation of mouse lymphocytes by anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibodies. I. Mode of action. Eur J Immunol. 1974;4(11):715–722. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830041103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kearney JF, Cooper MD, Lawton AR. B lymphocyte differentiation induced by lipopolysaccharide. III. Suppression of B cell maturation by anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibodies. J Immunol. 1976;116(6):1664–1668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pone EJ, et al. BCR-signalling synergizes with TLR-signalling for induction of AID and immunoglobulin class-switching through the non-canonical NF-κB pathway. Nat Commun. 2012;3:767. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avalos AM, Busconi L, Marshak-Rothstein A. Regulation of autoreactive B cell responses to endogenous TLR ligands. Autoimmunity. 2010;43(1):76–83. doi: 10.3109/08916930903374618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peitz M, Pfannkuche K, Rajewsky K, Edenhofer F. Ability of the hydrophobic FGF and basic TAT peptides to promote cellular uptake of recombinant Cre recombinase: a tool for efficient genetic engineering of mammalian genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(7):4489–4494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032068699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark EA, Ledbetter JA. Activation of human B cells mediated through two distinct cell surface differentiation antigens, Bp35 and Bp50. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(12):4494–4498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poltorak A, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282(5396):2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieg AM, et al. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA trigger direct B-cell activation. Nature. 1995;374(6522):546–549. doi: 10.1038/374546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwenk F, Kuhn R, Angrand PO, Rajewsky K, Stewart AF. Temporally and spatially regulated somatic mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(6):1427–1432. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.6.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sears R, et al. Multiple Ras-dependent phosphorylation pathways regulate Myc protein stability. Genes Dev. 2000;14(19):2501–2514. doi: 10.1101/gad.836800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diehl JA, Cheng M, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β regulates cyclin D1 proteolysis and subcellular localization. Genes Dev. 1998;12(22):3499–3511. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature. 1995;378(6559):785–789. doi: 10.1038/378785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meijer L, et al. GSK-3-selective inhibitors derived from Tyrian purple indirubins. Chem Biol. 2003;10(12):1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yusuf I, Zhu X, Kharas MG, Chen J, Fruman DA. Optimal B-cell proliferation requires phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent inactivation of FOXO transcription factors. Blood. 2004;104(3):784–787. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dansen TB, Burgering BM. Unravelling the tumor-suppressive functions of FOXO proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2008;18(9):421–429. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donahue AC, Fruman DA. PI3K signaling controls cell fate at many points in B lymphocyte development and activation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15(2):183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siebenlist U, Brown K, Claudio E. Control of lymphocyte development by nuclear factor-kappaB. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(6):435–445. doi: 10.1038/nri1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu X, et al. Analysis of the major patterns of B cell gene expression changes in response to short-term stimulation with 33 single ligands. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7141–7149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leslie NR, Downes CP. PTEN: The down side of PI 3-kinase signalling. Cell Signal. 2002;14(4):285–295. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285(5430):1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khwaja A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Wennström S, Warne PH, Downward J. Matrix adhesion and Ras transformation both activate a phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16(10):2783–2793. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cabodi S, et al. Convergence of integrins and EGF receptor signaling via PI3K/Akt/FoxO pathway in early gene Egr-1 expression. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218(2):294–303. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young RM, Staudt LM. Targeting pathological B cell receptor signalling in lymphoid malignancies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(3):229–243. doi: 10.1038/nrd3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu H, Zou YR, Rajewsky K. Independent control of immunoglobulin switch recombination at individual switch regions evidenced through Cre-loxP-mediated gene targeting. Cell. 1993;73(6):1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90644-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strasser A, et al. Enforced BCL2 expression in B-lymphoid cells prolongs antibody responses and elicits autoimmune disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(19):8661–8665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]