Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the health outcomes and economics associated with the current guidance relating to the prevention of falls in the elderly through vitamin D supplementation.

Setting

UK.

Participants

UK population aged 60 years and above.

Interventions

A Markov health state transition model simulated patient transitions between key fall-related outcomes using a 5-year horizon and annual cycles to assess the costs and benefits of empirical treatment with colecalciferol 800 iu daily.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Costs and health outcomes attributable to fall prevention following vitamin D supplementation.

Results

Our model shows that treating the UK population aged 60 years and above with 800 iu colecalciferol would, over a 5-year period: (1) prevent in excess of 430 000 minor falls; (2) avoid 190 000 major falls; (3) prevent 1579 acute deaths; (4) avoid 84 000 person-years of long-term care and (5) prevent 8300 deaths associated with increased mortality in long-term care. The greatest gains are seen among those 75 years and older. Based on reduction in falls alone, the intervention in all adults aged 65+ is cost-saving and leads to increased quality adjusted life years. Treating all adults aged 60+ incurs an intervention cost of £2.70bn over 5 years, yet produces a −£3.12bn reduction in fall-related costs; a net saving of £420M. Increasing the lower bound age limit by 5-year increments increases budget impact to −£1.17bn, −£1.75bn, and −£2.06bn for adults 65+, 70+ and 75+, respectively.

Conclusions

This study shows that treatment of the elderly UK population with colecalciferol 800 iu daily would be associated with reductions in mortality and substantial cost-savings through fall prevention.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS, GERIATRIC MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Age-group specific determination of health costs related to falling.

A conservative health economic model which interprets current guidance on prevention of falls using vitamin D therapy is highly cost effective in the treatment of adults over a 5-year time horizon.

Conservative estimation of costs of falls presenting to accident and emergency (A+E) only.

Fall prevention with empirical vitamin D 800 iu daily is associated with a reduced mortality comparable to that found in meta-analyses.

The role of vitamin D in fall prevention remains controversial.

Introduction

Vitamin D is increasingly recognised as an important sterol hormone with ubiquitous expression of the vitamin D receptor throughout the body's organs.1 While the effects of vitamin D on bone are well recognised there is increasing appreciation of its extraskeletal effects.2 Indeed, vitamin D deficiency is implicated in diseases beyond calcium metabolism such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis and cancer.2 With a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in the general population, increasing attention is turning to the positive impact of vitamin D replacement therapy.

Meta-analytic data reveal that vitamin D treatment is associated with reduced risk of fractures in the elderly only in doses at or above roughly 800 iu daily.3 Yet, these conclusions are disputed, as others argue that aetiological mechanisms such as bone mineralisation is unchanged through vitamin D intervention.4 However, falls are a particularly important event in the aetiology of fractures, as well as contributing to other morbidities, hospitalisation and institutionalisation in the elderly. Again, the data regarding falls has been confounded by inclusion of data relating to different doses, additional calcium supplementation and length of study.5 A meta-analytic study suggested a significant reduction in the risk of falls in elderly participants only in studies using doses of 700 iu of vitamin D or above.6 Again, the study has been criticised, yet a more recent review of the data by the American and British Geriatric Societies conclude that vitamin D therapy should be given to elderly participants at risk of falls and at a dose of at least 800 iu per day.7 They conclude that the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one fall is 10 compared with a NNT of 13 associated with exercise training. While evidence points to doses of at least 800 iu daily in fall prevention strategies in elderly participants, a letter from the Chief Medical Officers in the UK recommends a smaller dose of 400 iu daily for all participants over 65 years of age at risk of vitamin D deficiency.8

Universal vitamin D supplementation in older adults has been found to be a cost-effective strategy for fall prevention in the USA,9 and also in Western European populations (including the UK) but using fractures as the primary modifiable outcome.10–12

While the data suggest a positive impact of vitamin D therapy on fall prevention, there are no data which interpret the financial impact of vitamin D treatment on the UK population. Thus, based on the American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society (AGS/BGS) guidance7 in terms of a dose of at least 800 iu daily together with recommendations of the CMOs of the UK8 supporting treatment of a UK elderly population, we evaluated the cost-effectiveness and budget impact of treating the older adult (age 60 years and above) UK population with at least 800 iu of vitamin D daily with regard to its impact on falls.

Methods

A Markov health state transition model was constructed in Microsoft Excel to simulate patient transitions through a simplified patient pathway representing the key fall-related outcomes described in a detailed audit of UK accident and emergency department (A&E) records.13 The model conservatively used a 5-year horizon and annual cycles to assess the costs and benefits of treatment with colecalciferol 800 iu daily. The payer perspective was that of the UK taxpayer taking National Health Service (NHS) and Social Care expenditure into account.

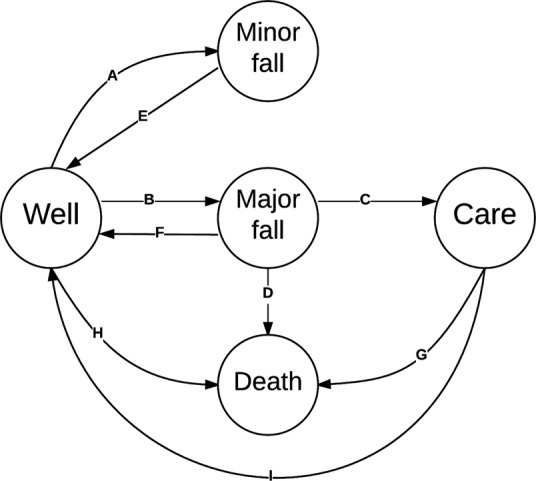

Health states

As described in figure 1, patients enter the model in the ‘Well’ state, and during each cycle it was assumed they lived in an independent community setting. During each cycle patients could experience either: (1) a ‘Minor fall’, necessitating A&E attendance but no admission and either no follow-up, outpatient follow-up or general practitioner (GP) follow-up; or (2) a ‘Major fall’ with admission to hospital via A&E and either discharge to home with follow-up or transfer to postacute care; or (3) death. Those experiencing a minor fall were assumed to make a full recovery as were those who had a major fall but did not require postacute care or died in hospital. Patients transferred to postacute care could return to independent living in their first year, thereafter the remainder were assumed to require long-term residential or nursing care.

Figure 1.

Markov health state transition model representing unintentional falls in older people. Key: ‘Well’, No fall in cycle and living at home; ‘Minor fall’, Fall resulting in A&E attendance but no admission; ‘Major fall’, Fall resulting in hospital admission; ‘Care’, No fall in cycle and living in care facility; and ‘Death’, from any cause. A&E, accident and emergency.

Health state transitions

Annual rates of accident and emergency admission were used to define age-group dependent probability of minor and major unintentional falls.13 These were derived by Scuffham et al, from a detailed analysis of UK sentinel databases are used to record mode of arrival at A&E, circumstances of the accident (cause), injury sustained, and deployment (eg, referral to GP). It was conservatively assumed that: each patient experiences just one fall event in a given year; and that future probability of falling is not conditional on fall history. Acute phase outcomes following admission for a major fall (death and discharge to post-acute care) were also defined.13 Age-group dependent all-cause mortality was applied equally to those remaining fall-free and those recovering fully from either a minor or major fall.14 For those in long-term care, the death rate observed by Bebbington et al15 during their longitudinal survey of 2540 admitted residents from 18 local authorities was conservatively applied. The probability of returning home in the first year after admission to long-term care was also applied from the Bebbington study. The transitions are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Transition probabilities between Markov health states (see figure 1)

| Transition | Description | Source | Age group (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60–64 | 65–69 | 70–74 | ≥75 | |||

| A | Probability of minor fall | Scuffham | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 5.8 |

| B | Probability of major fall | Scuffham | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 3.7 |

| C | Probability of long-term care following major fall | Scuffham | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.6 | 27.4 |

| D | Probability of death following major fall | Scuffham | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| E | Recovery following minor fall | Assumption | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| F | Recovery following major fall | 1-C-D | 99.8 | 99.6 | 90.7 | 71.7 |

| G | Probability of death while in care | Bebbington* | – | – | 20.6 | 20.6 |

| H | Probability of death from independent living | ONS | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 7.5 |

| I | Probability of return to independent living | Bebbington† | – | – | 3.8 | 3.8 |

*Conservatively estimated as that applicable to residential care.

†93/2450 older adults admitted to institutional care observed over 42 months. As the survival distribution of ‘returners’ is unknown the model conservatively estimates that they occur in the first year only following a major fall.

Treatment

The intervention under consideration is empiric treatment of all older adults aged 60 years and over with colecalciferol 800 iu daily. While this considers the older adult cohort preceding that recommended by the UK chief medical officers,8 it takes in the age cohorts examined by Scuffham et al13 with respect to falling, thus providing evidence to where the economic boundary of ‘older’ adulthood may lie with respect to fall prevention. The daily dose of colecalciferol administered is higher than the 400 iu jointly recommended by the UK CMOs because daily doses less than 700 iu have been shown to be ineffective in preventing falls in older adults, while patients treated with between 700 and 1000 iu have a shown a lower relative risk of falling (RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.71 to 0.92)).6 This treatment effect was applied equally to falls of any severity. The comparator was assumed to be current standard of care.

In terms of adverse effects of treatment we assumed none associated with vitamin D 800 iu daily treatment in line with the recent US Preventative Services Task Force finding of adequate evidence that the harms of treatment of vitamin D deficiency are small to none.16

Costs

Within our model, we selected the price of only licensed 800 iu vitamin D formulations available for prescription in the UK. We chose these preparations as there is a specific NHS tariff making calculations straightforward but also the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) stipulate that where a licensed product exists, unlicensed products should not be used.17

Therefore daily colecalciferol 800 iu treatment was assumed to be met by proprietary oral capsules as the lowest cost option in the British National Formulary (BNF).18 Fall-related costs were those listed13 and indexed to 2014 prices.19 All costs are summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Costs to NHS relating to falls and vitamin D treatment

| Description | GBP2014 | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Annual cost of daily vitamin D 800 IU supplementation | £43.83 | BNF |

| Ambulance journey | £306 | Scuffham |

| GP consultation | £31 | |

| A&E attendance | £111 | |

| Return to residence, attend OP | £116 | |

| Return to residence, attend GP | £31 | |

| Long-term care (6 months) | £16 388 | |

| Minor fall (weighted) | ||

| 60–64 | £442 | |

| 65–69 | £456 | |

| 70–74 | £466 | |

| ≥75 | £462 | |

| Major fall (weighted HRG acute costs) | ||

| 60–64 | £2622 | |

| 65–69 | £2766 | |

| 70–74 | £3603 | |

| ≥75 | £3537 |

A&E, accident and emergency; BIM, Budget Impact Model; BNF, British National Formulary; GP, general practitioner; HRG, Healthcare Resource Group; NHS, National Health Service; ONS, Office of National Statistics; OP, outpatients.

Utilities

Baseline utility in the ‘Well’ state was defined according to 5-year age group and the UK value set for the EQ-5D-3 L.20 Falls were assumed to confer a disutility associated with severe fear of falling.21 Postacute institutional care was also associated with disutility compared to age-gender matched counterparts reported in a study of Australian older adults.22 Hospital admission following a major fall was conservatively assumed to incur the same disutility as postacute care for 10 days, the average length of stay for HRG R29.6, Tendency to fall, not elsewhere classified.23 Utilities are summarised in table 3.

Table 3.

Health state utilities by age-group

Budget impact population

Budget impact calculations were based on the older adult population of the UK at the 2011 census.24

Results

Outcomes

Over the 5-year model horizon, our model suggests that empiric colecalciferol treatment at 800 iu daily among older adults aged 60 years and over in the UK would: (1) prevent in excess of 430 000 minor falls; (2) avoid 190 000 major falls; (3) prevent 1579 acute deaths; (4) avoid 84 000 person-years of long-term care; and (5) avoid a further 8300 deaths associated with increased mortality in long-term care (table 4). The greatest gains are seen among those aged 75 years and older which would account for 51% of preventable minor falls, 75% of preventable major falls, 96% of person years in care avoided and 94% avoidable attributable mortality.

Table 4.

Comparison of 5-year fall-related outcomes for current care versus empiric vitamin D maintenance therapy

| Age group | Current | Vitamin D | Δ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minor falls | |||

| 60–64 | 449 271 | 363 910 | 85 360 |

| 65–69 | 350 460 | 283 875 | 66 585 |

| 70–74 | 328 891 | 266 484 | 62 407 |

| ≥75 | 1 190 867 | 968 252 | 222 615 |

| Major falls | |||

| 60–64 | 64 769 | 52 463 | 12 306 |

| 65–69 | 77 452 | 62 737 | 14 715 |

| 70–74 | 109 630 | 88 828 | 20 802 |

| ≥75 | 761 374 | 619 046 | 142 328 |

| Deaths from falls | |||

| 60–64 | 149 | 121 | 28 |

| 65–69 | 333 | 270 | 63 |

| 70–74 | 713 | 577 | 135 |

| ≥75 | 7233 | 5881 | 1352 |

| Person-years in care | |||

| 60–64 | – | – | – |

| 65–69 | – | – | – |

| 70–74 | 18 338 | 14 857 | 3481 |

| ≥75 | 426 696 | 346 408 | 80 288 |

| Deaths from care | |||

| 60–64 | – | – | – |

| 65–69 | – | – | – |

| 70–74 | 1932 | 1566 | 367 |

| ≥75 | 42 586 | 34 625 | 7961 |

Cost-effectiveness

Compared to current care, treating all adults aged 60 years and over with colecalciferol 800 iu daily would have an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of £19 759 per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained based on a reduction in falls alone. The same intervention in all adults aged 65 years and over, as recommended by the UK CMOs8 dominates current care, by being cost-saving and leading to increased QALYs (table 5).

Table 5.

Cost-effectiveness results of alternative treatment strategies (per person treated)

| Strategy | Incremental costs | Incremental QALYs | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treat all adults ≥60 years | £23.52 | 0.0012 | £19 759 |

| Treat all adults ≥65 years | −£34.19 | 0.0014 | Dominant |

| Treat all adults ≥70 years | −£147.01 | 0.0018 | Dominant |

| Treat all adults ≥75 years | −£419.88 | 0.0027 | Dominant |

ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality adjusted life year.

Budget impact

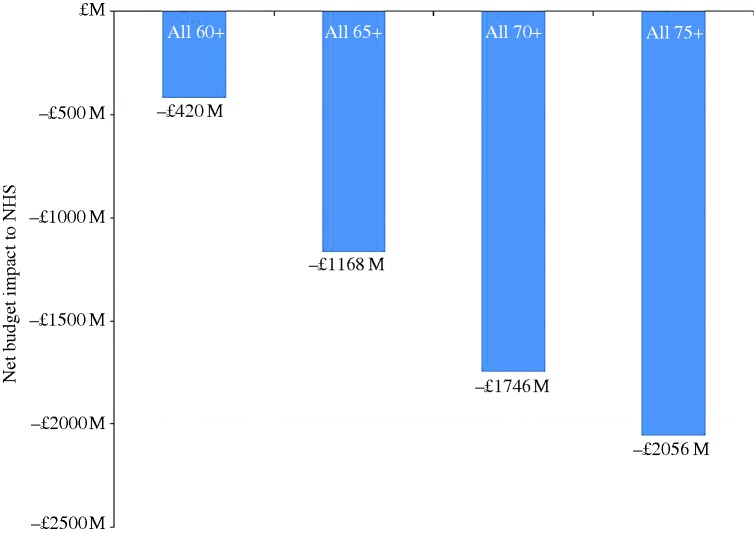

The costs and net budget impact of alternative age-bound strategies for use of empiric maintenance treatment with colecalciferol 800 iu daily are shown in table 6. Treating all adults aged 60 years and over, would incur an intervention cost of £2.70bn over 5 years, yet over the same period a −£3.12bn reduction in fall-related costs would produce a net saving of £420M. Increasing the lower bound age limit by 5-year increments increases budget impact to −£1.17bn, −£1.75bn and −£2.06bn for intervention strategies applied to all adults aged 65+, aged 70+ and aged 75+, respectively (figure 2).

Table 6.

Budget impact on NHS for alternative age-bound empiric vitamin D maintenance therapy strategies

| Strategy | Well | Minor fall | Major fall | Care after major fall | Long-term care | Total | Net BIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current care | |||||||

| All 60+ | £ M | £1062 M | £3472 M | £3540 M | £9378 M | £17 451 M | |

| All 65+ | £ M | £863 M | £3302 M | £3540 M | £9378 M | £17 083 M | |

| All 70+ | £ M | £703 M | £3088 M | £3540 M | £9378 M | £16 709 M | |

| All 75+ | £ M | £550 M | £2693 M | £3386 M | £8994 M | £15 623 M | |

| Empiric vitamin D maintenance | |||||||

| All 60+ | £2703 M | £944 M | £2857 M | £2886 M | £7642 M | £17 032 M | −£420 M |

| All 65+ | £1903 M | £767 M | £2717 M | £2886 M | £7642 M | £15 915 M | −£1168 M |

| All 70+ | £1270 M | £626 M | £2540 M | £2886 M | £7642 M | £14 963 M | −£1746 M |

| All 75+ | £771 M | £490 M | £2216 M | £2761 M | £7330 M | £13 567 M | −£2056 M |

NHS, National Health Service.

Figure 2.

Budget impact results for alternative treatment strategies.

Discussion

Our study shows that treating all adults over the age of 65 with vitamin D at doses of 800 iu daily would result in a substantial cost-saving to the UK NHS of £1.2 billion over 5 years through prevention of some 530 000 falls, 84 000 person-years in long-term care, and almost 10 000 premature deaths. Additionally, the empiric treatment of younger seniors from the age of 60 would also be cost-saving, albeit less so. The main relief of burden on health and social care expenditure would arise from avoidance of long-term care following a fall in those aged 70 years and over. These data are consistent with cost-effectiveness assessments of universal vitamin D supplementation in older adults in the USA9 and also in Western European populations but using fractures as the primary modifiable outcome.10 11

The ‘memory-less’ property of our Markov model structure introduced a conservative assumption that fall history does not influence future risk of falling. Additionally, falls among those receiving long-term care was not modelled. Our model also applied all-cause mortality as the background death rate, which include deaths from unintentional falls, effectively reducing the ‘at-risk’ population. Therefore our estimates of cost-effectiveness are likely conservative.

Sustainability of treatment effect is an important consideration in any economic analysis. Active forms of vitamin D, including colecalciferol, do not need hydroxylation in the kidney, so their effect on falls should be influenced less by age-related decline in kidney function than the effect of supplemental vitamin D. The duration of the eight randomised controlled trials included in the primary efficacy meta-analysis we modelled,6 was 2, 3, 5, 12, 20, 24 and 36 months suggesting that the pooled effect is consistent over longer time periods. In addition we conservatively set a model horizon of 5 years to avoid speculative extrapolation of long-term benefits with increasing uncertainty.

Falls are a particularly common problem in the elderly person accounting for 10% of emergency hospital visits and 6% of hospital admissions with risk increasing with increasing age.25 Rather than a benign process, falls are a predictor of increasing morbidity, mortality and importantly institutionalisation. In consequence, falls present a significant risk to health and are costly. We based our calculations on the health economic evaluation of falls in the UK.13 This data included the cost of falls to the NHS and social care budgets. While our calculated cost-savings are great, the estimates used to support these calculations have been conservative. Indeed, the older person who has fallen suffers greater decline in activities of daily living as well as greater risk of institutionalisation.26 Those who return to independent living following a fall often require domestic care support, costs we did not factor in our evaluation. With this in mind, we have demonstrated that 800 iu colecalciferol daily is a cost-effective treatment purely based on fall prevention in individuals 60 years and over. The cost per QALY of £19 759 is within the expected economic cost per QALY threshold of £20 000 advocated by the National Institute of Care Excellence (NICE). This is comparable to evaluations for the prevention of ischaemic heart disease with statin therapy.27 Similarly, dominant QALY costs, (indicating that there are net savings accrued through fall prevention with vitamin D treatment), were noted with the application of the recommendations of the CMOs letter8 for the treatment of all patients aged 65 years and over (table 5).

Vitamin D is an important sterol hormone involved in calcium metabolism with recognition of its important role in musculoskeletal health. Evidence reveals that vitamin D deficiency is common in the UK with studies suggesting a prevalence as high as 50%28 and even higher in certain populations such as the elderly and institutionalised.29 Decreased bone mineralisation, increased fracture risk as well as increased risk of falls are associated with vitamin D deficiency30–32 and evidence would point to the improvement in some of these parameters following treatment, particularly in the elderly.3 6 33 However, not all studies conclude a reduction in falls and such discrepancies may be a consequence of the use of different formulations (ergocalciferol or colecalciferol), different doses of vitamin D, differing baseline vitamin D status and also differing populations.5 34 However, guidelines on fall prevention has evaluated the evidence and support the treatment of individuals with deficiency, or potential deficiency, at risk of falls with at least 800 iu of vitamin D daily.7 Similarly, UK CMOs also advocate vitamin D treatment, yet the 400 iu dose advocated may be ineffective in terms of preventing deficiency, falls and fractures in an elderly population.3 6 In consequence, we elected an 800 iu dose as the minimal, guidance-advocated dose for fall prevention in the elderly.

The importance of vitamin D in an adult population can be seen at the extreme end of the clinical spectrum as osteomalacia, with pseudofractures and profound proximal muscle weakness. Symptoms and signs resolve following treatment and so it seems plausible that vitamin D therapy too has beneficial effects in non-osteomalacic vitamin D deficiency.35 This is supported by studies revealing dose dependent reduction in falls and fractures3 6 33 which may accrue only with vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency, a common problem in the elderly population. Factors contributing to the reduced risk of falls following vitamin D treatment include improved muscle strength36 37 as well as improved balance.34 Indeed, improved muscle mitochondrial oxidative function38 as well as muscle energy metabolism39 following vitamin D treatment may provide mechanistic explanations for improved strength and endurance. Histologically, reduced muscle fibre number and changes in muscle fibre type my contribute further to the sarcopaenia and myopathy found with aging and vitamin D deficiency40 and may improve following treatment with vitamin D.41

Our study also shows that the reduced risk of falls associated with treating an elderly population with vitamin D is associated with a substantial reduction in premature deaths. Studies reveal increased mortality associated with lower 25OHD concentrations although this relationship has been considered to be an epiphenomenon of illness. However, recent data support the role of reduced mortality following vitamin D treatment.42–45 In particular, colecalciferol rather than ergocalciferol appears to offer superiority in mortality reduction.44 The single figure per cent reduction in mortality seen in such studies is in keeping with that calculated in our study.

With respect to UK public health policy regarding vitamin D supplementation in older adults,8 we believe, in light of the clinical and economic evidence, that the current advice is flawed. First, the recommendation of universal supplementation of colecalciferol 400 iu (10 µg) daily has been shown to be ineffective in the prevention of either falls6 or fractures.3 Expert guidelines suggest a minimum daily supplement of 800 iu in those at risk.7 Second, the optimal method of procurement is not clearly stated, with OTC supply being given equal weighting to prescription. We contend that prescribed therapy should be favoured over OTC preparations, not just on the grounds of quality and safety18 but also as a means of improving patient compliance with treatment19 and ensuring equity of access to all older adults who remain exempt from prescription charges across the UK.

In conclusion, our data show that with only reference to fall prevention, the provision of empiric colecalciferol therapy to all older adults in the UK potentially offers considerable cost-saving to the UK NHS over a 5-year horizon. Accompanying such financial benefits, a reduction in attributable premature mortality and increase in quality-adjusted life years could also be expected.

Footnotes

Contributors: JSD and CDP conceived the idea for this paper and jointly researched and wrote the paper. JS contributed to research and the authoring of the paper.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: JS Davies provides medical consultancy advice to Internis Pharmaceuticals and MEDA, the manufacturers of vitamin D products and has undertaken speaker meetings for Internis Pharmaceuticals. CDP has undertaken consultancy work for Internis Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of vitamin D products, Norgine and Sandoz. JS has nothing to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data are available.

References

- 1.Norman AW. From vitamin D to hormone D: fundamentals of the vitamin D endocrine system essential for good health. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:491S–9S. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S et al. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality-a review of recent evidence. Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:976–89. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Orav EJ et al. A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med 2012;367:40–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reid IR, Bolland MJ, Grey A. Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2013;6736:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitamin D and falls. lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=UA&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=3&SID=X2nclIhxG5y5jkoL5B6&page=1&doc=1 (accessed 6 Sep 2014).

- 6.Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB et al. Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2009;339:b3692 10.1136/bmj.b3692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panel on Prevention of Falls in Older Persons, American Geriatrics Society and British Geriatrics Society. Summary of the Updated American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:148–57. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies SC, Jewell T, McBride M et al. Vitamin d—advice on supplements for at risk groups. London: Department of Health, 2012. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vitamin-d-advice-on-supplements-for-at-risk-groups [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee RH, Weber T, Colón-Emeric C. Comparison of cost-effectiveness of vitamin D screening with that of universal supplementation in preventing falls in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:707–14. 10.1111/jgs.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiligsmann M, Ben Sedrine W, Bruyère O et al. Cost-effectiveness of vitamin D and calcium supplementation in the treatment of elderly women and men with osteoporosis. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:20–5. 10.1093/eurpub/cku119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarca K, Durand-Zaleski I, Roux C et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of hip fracture prevention with vitamin D supplementation: A Markov micro-simulation model applied to the French population over 65years old without previous hip fracture. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:1797–806. 10.1007/s00198-014-2698-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poole CD, Smith JC, Davies JS. The short-term impact of vitamin D-based hip fracture prevention in older adults in the United Kingdom. J Endocrinol Invest 2014;37:811–17. 10.1007/s40618-014-0109-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scuffham P, Chaplin S, Legood R. Incidence and costs of unintentional falls in older people in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Heal 2003;57:740–4. 10.1136/jech.57.9.740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Office for National Statistics. Death Registrations Summary Tables—England and Wales, 2011 (Final) 2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/vsob1/death-reg-sum-tables/2011--final-/index.html

- 15.Bebbington A, Darton R, Netten A.2000. Elderly people admitted to residential and nursing homes : 42 months on. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/pdf/p051.pdf.

- 16.US Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement: Vitamin D Deficiency: Screening. 2014. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/vitamin-d-deficiency-screening (accessed 1 Dec 2014).

- 17.MHRA. Off-label or unlicensed use of medicines: prescribers’ responsibilities. http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Safetyinformation/DrugSafetyUpdate/CON087990 (accessed 14 Apr 2013).

- 18.British Medical Association, Royal Pharmaceutical Society. British National Formulary. 68th edn London, UK: BMJ Publishing & Pharmaceutical Press, 2014. http://www.bnf.org [Google Scholar]

- 19.HM Treasury. 2012 GDP deflators 2012. http://www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/data_gdp_index.htm (accessed 29 Mar 2013).

- 20.Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S. UK Population Norms for EQ-5D (Discussion Paper 172) 1999.

- 21.Thiem U, Klaaßen-Mielke R, Trampisch U et al. Falls and EQ-5D rated quality of life in community-dwelling seniors with concurrent chronic diseases: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014;12:2 10.1186/1477-7525-12-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couzner L, Crotty M, Norman R et al. A comparison of the EQ-5D-3L and ICECAP-O in an older post-acute patient population relative to the general population. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2013;11:415–25. 10.1007/s40258-013-0039-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health & Social Care Information Centre. Hospital Episode Statistics, Admitted Patient Care, England—2012–13 [NS]. Leeds, UK: 2013. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/searchcatalogue?productid=13264&q=title:‘Hospital+Episode+Statistics,+Admitted+patient+care+-+England’&sort=Relevance&size=10&page=1#top [Google Scholar]

- 24.Office for National Statistics. Statistical bulletin: Annual Mid-year Population Estimates for England and Wales, 2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/ppo-estimate/population-estimates-for-england-and-wales/mid-2012/mid-2012-population-estimates-for-england-and-wales.html#tab-background-notes

- 25.Tinetti ME. Clinical practice. Preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med 2003;348:42–9. 10.1056/NEJMcp020719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuller GF. Falls in the elderly. Am Fam Physician 2000;61:2159–68, 2173–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ward S, Lloyd Jones M, Pandor A et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of statins for the prevention of coronary events. Health Technol Assess 2007;11:1–160, iii– iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyppönen E, Power C. Hypovitaminosis D in British adults at age 45 y: nationwide cohort study of dietary and lifestyle predictors. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:860–8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17344510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zgaga L, Theodoratou E, Farrington SM et al. Diet, environmental factors, and lifestyle underlie the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in healthy adults in Scotland, and supplementation reduces the proportion that are severely deficient. J Nutr 2011;141:1535–42. 10.3945/jn.111.140012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Girgis CM, Clifton-Bligh RJ, Turner N et al. Effects of vitamin D in skeletal muscle: falls, strength, athletic performance and insulin sensitivity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;80:169–81. 10.1111/cen.12368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Priemel M, von Domarus C, Klatte TO et al. Bone mineralization defects and vitamin D deficiency: histomorphometric analysis of iliac crest bone biopsies and circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D in 675 patients. J Bone Miner Res 2010;25:305–12. 10.1359/jbmr.090728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanders KM, Scott D, Ebeling PR. Vitamin D deficiency and its role in muscle-bone interactions in the elderly. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2014;12:74–81. 10.1007/s11914-014-0193-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murad MH, Elamin KB, Abu Elnour NO et al. Clinical review: The effect of vitamin D on falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:2997–3006. 10.1210/jc.2011-1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcelli C, Chavoix C, Dargent-Molina P. Beneficial effects of vitamin D on falls and fractures: is cognition rather than bone or muscle behind these benefits? Osteoporos Int 2015;26:1–10. 10.1007/s00198-014-2829-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chalmers J, Conacher WD, Gardner DL et al. Osteomalacia—a common disease in elderly women. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1967;49:403–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diamond T, Wong YK, Golombick T. Effect of oral cholecalciferol 2,000 versus 5,000 IU on serum vitamin D, PTH, bone and muscle strength in patients with vitamin D deficiency. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:1101–5. 10.1007/s00198-012-1944-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreira-Pfrimer LD, Pedrosa MA, Teixeira L et al. Treatment of vitamin D deficiency increases lower limb muscle strength in institutionalized older people independently of regular physical activity: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Ann Nutr Metab 2009;54:291–300. 10.1159/000235874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sinha A, Hollingsworth KG, Ball S et al. Improving the vitamin D status of vitamin D deficient adults is associated with improved mitochondrial oxidative function in skeletal muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:E509–13. 10.1210/jc.2012-3592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rana P, Marwaha RK, Kumar P et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on muscle energy phospho-metabolites: a (31)P magnetic resonance spectroscopy-based pilot study. Endocr Res 2014;39:152–6. 10.3109/07435800.2013.865210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irani PF. Electromyography in nutritional osteomalacic myopathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1976;39:686–93. 10.1136/jnnp.39.7.686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ceglia L, Niramitmahapanya S, da Silva Morais M et al. A randomized study on the effect of vitamin D3 supplementation on skeletal muscle morphology and vitamin D receptor concentration in older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:E1927–35. 10.1210/jc.2013-2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D et al. Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(7):CD007470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Autier P, Gandini S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1730–7. 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chowdhury R, Kunutsor S, Vitezova A et al. Vitamin D and risk of cause specific death: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational cohort and randomised intervention studies. BMJ 2014;348:g1903 10.1136/bmj.g1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grant WB, Schwalfenberg GK, Genuis SJ et al. An estimate of the economic burden and premature deaths due to vitamin D deficiency in Canada. Mol Nutr Food Res 2010;54:1172–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]