Abstract

Background

Metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) is found to be overexpressed and associated with clinicopathological features in patients with cancer.

Objectives

To evaluate the clinical value of MALAT1 as a prognostic marker in human cancers by a comprehensive meta-analysis of published studies.

Data sources

The data on the prognostic impact of MALAT1 in cancer were collected from 11 September 2003 to 10 July 2015.

Setting and participants

Fourteen eligible studies with a total of 1373 patients conducted in 3 countries (9 in China, 3 in Japan and 2 in Germany) were matched to our inclusion criteria.

Outcome measures

Pooled HRs with 95% CIs were calculated to estimate the strength of the link between MALAT1 and clinical prognoses. The combined HRs heterogeneity was tested using a χ2-based Cochran Q test and Higgins I2 statistic. Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot with Egger's bias indicator test.

Results

A significant association between MALAT1 overexpression and poor overall survival (OS) (HR=1.95; 95% CI 1.57 to 2.41) was observed. Residence region (Germany and China), cancer type (respiratory, digestive or other system disease), sample size and paper quality did not alter the predictive value of MALAT1 on OS in investigated cancers. MALAT1 expression was an independent prognostic marker for OS in patients with cancer using univariate and multivariate analyses. Subgroup analysis showed that the elevated MALAT1 appeared to be a powerful prognostic marker for patients with respiratory, digestive and other system cancers. A similar effect was also seen in different regions. Furthermore, the overexpression of MALAT1 was associated with disease-free, recurrence-free and progression-free survivals.

Conclusions

MALAT1 may potentially be used as a new prognostic marker to predict poorer survival of patients with cancer. More clinical studies on the different types of human cancer not yet investigated need to be conducted.

Keywords: MOLECULAR BIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the most up-to-date meta-analysis article to evaluate the clinical value of MALAT1 as a prognostic marker in human cancers.

MALAT1 expression was an independent prognostic marker for poor overall survival in patients with cancer.

The overexpression of MALAT1 was found to be associated with disease-free, recurrence-free and progression-free survival.

The major limitation was a relatively small number of studies in different regions collected, which might reduce the applicability across different ethnicities.

More clinical studies need to be conducted to evaluate the prognostic potential of MALAT1 in other types of cancer not yet investigated.

Introduction

Non-coding RNAs are types of RNA which are not translated into proteins, usually including long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), microRNA (miRNA, miR), small interfering RNA (short interfering RNA, silencing RNA, siRNA) and PIWI-interacting RNA (piRNA).1 2 Recent studies have indicated that at least 75% of the human genome is transcribed into RNAs, which are mostly lncRNAs, longer than 200 nucleotides (nt) (http://www.genome.gov/ENCODE). Emerging evidence suggests that lncRNAs have many biological actions, such as transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation by interfering with the promoter of gene, the reorganisation of chromatin, the induction of histone modification, the regulation of subcellular localisation and/or function of proteins and the production of endogenous siRNA.3 4 The dysregulation of lncRNAs has been found in various human cancers, including colorectal, ovarian, lung, gastric, liver and breast cancers.5–10 Some lncRNAs play a key role in cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis11–13 and may be used as potential and new biomarkers for the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of cancer.13 14

The metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1), also known as nuclear-enriched transcript 2 (NEAT2) and mascRNA, is a lncRNA consisting of more than 8700 nt located on chromosome 11q13 and discovered as a predictive marker for metastasis in early-stage, non-small cell lung cancer.15 It has been shown that MALAT1 plays an important role in cancer16 and acts as a transcriptional regulator for various genes, including those involved in cell proliferation, migration and metastasis. Several studies have shown the aberrant expression of MALAT1 in tumour tissues compared with normal tissues and reported its association with clinical progression in human cancers.17–20 Elevated MALAT1 expression is also found to be significantly correlated with peritoneal metastasis in patients with gastric cancer.21 A high level of MALAT1 expression may serve as a negative, unfavourable prognostic marker in patients with stage II/III colorectal cancer22 and may be associated with the invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer.23 The overexpression level of MALAT1 in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung is associated with patient survival.24 More recently, a study reported that the overexpression of MALAT1 in glioma tissues was positively correlated with grade and tumour size,18 suggesting that MALAT1 may serve as an authentic prognostic biomarker for patients with glioma.

In view of the fact that there is an association between MALAT1 expression and the clinicopathological features of human cancers, most studies reported so far are limited in their sample size and discrete outcomes. Therefore, we analyse all previously published data based on the robust evidence of the expression and impact of MALAT1 in tumorigenesis, and conduct a systematic review and quantitative meta-analysis to evaluate the clinical value of MALAT1 as a prognostic marker in human cancer.

Methods

Search strategy

The selected publications were identified by using up-to-date electronic databases, including PubMed, Medline, EMBASE, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Ovid and Cochrane library (see online supplementary information). Searching of the published data was in accordance with the systematic reviews and meta-analysis guidelines of tumour marker prognostic studies (REMARK), as described previously.25–27 The literature covered was restricted to publications in English.

The following key words were used for the search: “MALAT1 or MALAT-1 or NEAT2 or mascRNA”, “long non-coding RNA or lncRNA”, “cancer or carcinoma or tumour or neoplasia or neoplasm or malignancy or sarcoma”, “prognostic or prognosis”, “outcome”, “mortality”, “survival” and “recurrence”. The literature search was stopped at 10 July 2015.

Selection criteria and quality assessment

All the included studies were systematically reviewed and evaluated based on the reporting checklists MOOSE,28 REMARK27 and PRISMA.29 Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) information of study population and regions; (2) information of any type of human cancer; (3) description of study design; (4) investigation of the correlation between MALAT1 expression level and survival outcome; (5) description of MALAT1 measurement, such as quantitative PCR or in situ hybridisation in human tissue; (6) description of the relationship between MALAT1 and overall survival (OS), (7) description of the cut-off value of MALAT1; (8) period of follow-up. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) meta-analysis paper; (2) review paper; (3) non-English paper; (4) conference abstract; (5) non-human data; (6) paper lacking all HR, 95% CI and p values and raw data.

For quality control of a paper, all eligible studies were scored as previously reported.30 31 Briefly, the assessment was performed by two authors, who reached an agreement on all items assessed. The categories of score assessment included the scientific design (five items: study objective definition, study design, outcome definition, statistical consideration, statistical method and test description), laboratory methodology (seven items: blinding in the biological assays performance, tested factor description, tissue sample conservation, description of the relevant test procedure of the biological factor, description of the negative and positive control procedures, test reproducibility control, definition of the level of positivity of the test), generalisability (six items: patient selection criteria, patients’ characteristics, initial investigation, treatment description, source of samples, number of unassessable samples with exclusion causes) and results analysis (four items: follow-up description, survival analysis according to the biological marker, univariate analysis of the prognostic factors for survival, multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors for survival).30 Each item was scored as follows: 2 points if it was clearly defined in the article, 1 point if its description was incomplete or unclear and 0 point if it was not defined or was inadequate. The maximum theoretical score was 44 points. The final quality score was presented as percentage, which was calculated using the formula (the sum of the total points divided by 44 and multiplied by 100) (see online supplementary information). An optimal threshold was yet to be defined, which the cut-off point of 85% of the quality scores represented half of the investigated studies. Higher percentages reflected better reporting quality of the paper.

Data extraction

The extracted data included author name, journal name, year of publication, country in which study participants were enrolled, ethnicity, the number of patients, study design, the expression level of MALAT1, detection method, the clinical stage of the tumour, follow-up, treatment data, cut-off values, OS, HRs of elevated MALAT1 for OS, disease-free survival (DFS), progression-free survival (PFS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS), as well as their 95% CIs and p value. The HRs were obtained by three methods. In method 1, the HRs were obtained directly from publications. In method 2, the HRs were calculated from the total number of events and its p value with the formula: HR=[P0/(1−P0)]/[P1/(1−P1)], where P0 represents a 5-year survival rate in the group with low expression of MALAT1 and P1 represents a 5-year survival rate in the group with high expression of MALAT1.32 The formula of 95% CI was exp(lnHR±1.96×SE), where exp=exponential, lnHR=the natural logarithm HR and SE of HR. In method 3, the HRs were extracted from Kaplan–Meier curves (see online supplementary information). The HR estimate was reconstructed by extracting several survival rates at specified times from the survival curves using the Engauge Digitizer (V.4.1, http://digitizer.sourceforge.net).

Statistical analysis

The extracted data were analysed using STATA software V.10.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). The HRs with the corresponding 95% CIs were used to estimate the strength of the link between MALAT1 and clinical prognoses. The HRs with their 95% CIs and p values were collected from the original articles. However, if not available, we calculated the HRs and their 95% CIs using previously reported methods,32 33 as indicated above. A random-effect model (DerSimonian–Laird method) was applied if heterogeneity was observed, whereas a fixed-effect model was used in the absence of between-study heterogeneity. The factors contributing to heterogeneity were analysed by subgroup analysis, meta-regression or sensitivity analysis by a sequential omission of each individual study. The test for heterogeneity of combined HRs was carried out using a χ2-based Cochran Q test and Higgins I2 statistic. A p value of <0.05 or an I2 value of >50% was considered statistically significant. Publication bias was evaluated using a funnel plot with Egger's bias indicator test.34

Results

Data selection and characteristics of eligible studies

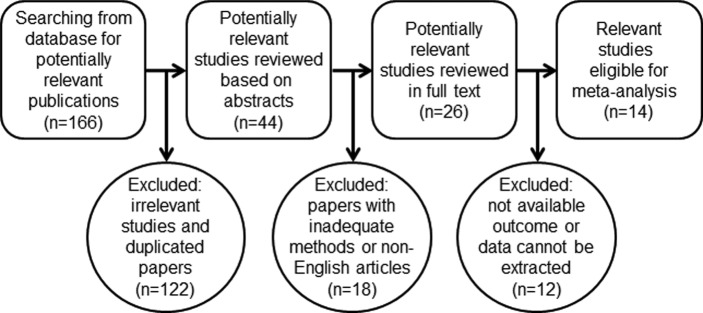

Based on the study design, our search with key terms disclosed 166 articles by 10 July 2015. The titles and abstracts were reviewed, and 122 irrelevant studies and duplicates were excluded. Eighteen studies were eliminated from the remaining 44 because different statistics methods had been used or the articles were not in English. After data extraction, 14 studies with a total of 1373 patients, conducted in three countries (nine in China, three in Japan and two in Germany), were matched to our inclusion criteria and were eligible for the meta-analysis (figure 1). The maximum and minimum sample sizes of patients were 222 and 19, respectively. The accrual period of these studies ranged from June 2003 to March 2015.

Figure 1.

Workflow of searching strategy in the meta-analysis.

The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in table 1. Among these 14 studies, a total of 10 different types of cancer were evaluated by this meta-analysis, including respiratory system carcinoma (three lung cancers),15 24 35 digestive system carcinoma (one hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), one gastric cancer, one colorectal cancer and two pancreatic cancers),21 22 36–38 urinary system carcinoma (two renal cell carcinomas and one bladder cancer),39–41 and other system carcinoma (one glioma, one osteosarcoma and one multiple myeloma).18 42 43 All specimens examined were tissues. The cut-off values of the high and low expression of MALAT1 in these studies were found to be inconsistent owing to different detection methods, such as quantitative PCR and in situ hybridisation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of MALAT1 studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study (year) |

Region | Tumour type | No. of patients | Tumour stage | Elevated (%) or p value | PT | SO | Cut-off value | M | Survival analysis | p Value | Follow-up (years) |

Quality score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ji et al, 200315 | Germany | Non-small cell lung cancer | 70 | I–III | 3 | NA | OS | Median | 3 | Univariate | 0.040 | 5 | 81.8 |

| Schmidt et al, 201124 | Germany | Non-small cell lung cancer | 222 | I–III | 35% | NA | OS | Mean | 1 | Univariate | 0.012 | 11 | 72.7 |

| Lai et al, 201236 | China | Hepatocellular carcinoma | 112 | NA | p=0.012 | NA | RFS | Mean | 1 | Multivariate | 0.003 0.013 |

3 | 86.4 |

| Cho et al, 201443 | Japan | Multiple myeloma | 36 | I–III | 3.01 | Yes | OS PFS |

Mean | 3 | Univariate | 0.313 0.001 |

4 | 86.4 |

| Dong et al, 201542 | China | Osteosarcoma | 19 | I–III | 2 | NA | OS | Mean | 2 | NA | 0.21 | 5 | 81.8 |

| Fan et al, 201441 | China | Bladder cancer | 95 | I–IV | 81% | NA | OS | Median | 1 | Multivariate | 0.008 | 2.5 | 81.8 |

| Liu et al, 201437 | China | Pancreatic cancer | 45 | I–IV | p=0.009 | NA | DSS | Mean | 1 | Multivariate Univariate |

0.007 0.036 |

5 | 86.4 |

| Okugawa et al, 201421 | Japan | Gastric cancer | 150 | III–IV | p<0.001 | NA | OS | Mean | 1 | Univariate | 0.105 | 5 | 81.8 |

| Pang et al, 201538 | China | Pancreatic cancer | 126 | I–IV | p<0.001 | No | OS | Median | 1 | Multivariate Univariate |

0.018 <0.001 |

5 | 93.2 |

| Zhang et al, 201540 | China | Renal cell carcinoma | 106 | I–IV | p<0.05 | No | OS | Mean | 3 | Univariate | 0.008 | 5 | 93.2 |

| Zheng et al, 201422 | China | Colorectal cancer | 146 | II–III | p<0.001 | NA | OS DFS |

Median Median |

1 | Multivariate Multivariate |

0.002 <0.001 |

5 | 86.4 |

| Hirata et al, 201539 | Japan | Renal cell carcinoma | 50 | I–IV | 7.93 | NA | OS | Median | 2 | Univariate | 0.01 | 5 | 81.8 |

| Ma et al, 201518 | China | Glioma | 118 | I–IV | p<0.001 | No | OS | Median | 1 | Multivariate Univariate |

0.002 <0.001 |

5 | 93.2 |

| Shen et al, 201535 | China | Lung cancer | 78 | NA | p<0.001 | NA | DFS | Mean | 3 | Univariate | 0.015 | 5 | 81.8 |

MALAT1 expression was examined using qRT-PCR, except for the Schmidt (2014) study, which used in situ hybridisation.

DFS, disease-free survival; DSS, disease-specific survival; M=method (1=HRs obtained directly from publications, 2=HRs calculated from the total number of events and its p value, 3=HRs extracted from Kaplan–Meier curves); NA, not available; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PT, preoperative treatment; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SO, survival outcome.

Association of MALAT1 expression with OS in human cancer

We obtained the HRs directly from eight studies and indirectly from six studies by calculation using methods 2 and 3 as described (also see online supplementary information). A significant association was found between elevated MALAT1 expression and poor OS in 10 types of cancer (pooled HR=1.95; 95% CI 1.57 to 2.41). There was no evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity across the studies (χ2=6.70, df=13, p=0.257; I2=18.0%).

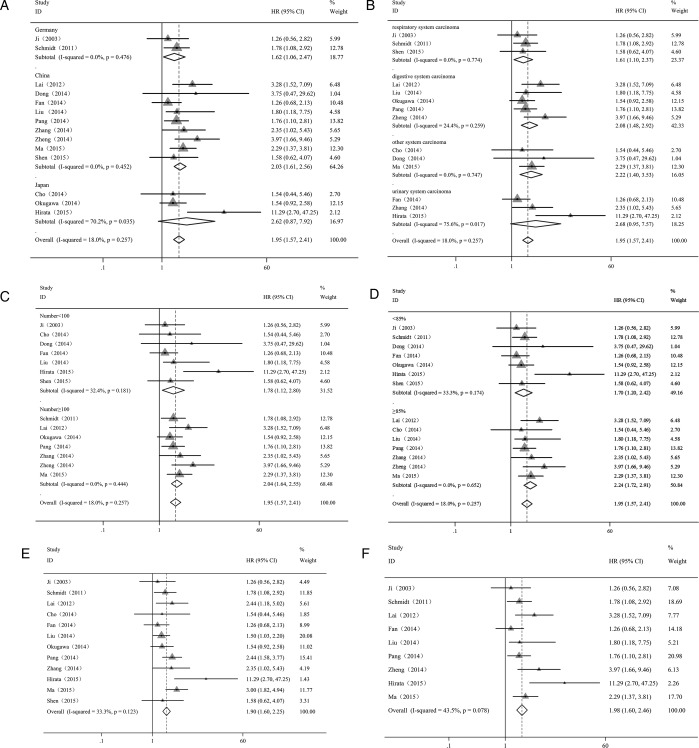

Subsequent analyses of subgroups were performed based on country, the type of cancer, sample size, the quality of the paper and the method of analysis (table 2; figure 2; see online supplementary information). We detected a significant correlation between overexpressed MALAT1 and poor OS in patients with cancer in China (HR=2.03; 95% CI 1.61 to 2.56) and Germany (HR=1.62; 95% CI 1.06 to 2.47), but not in Japan (HR=2.62; 95% CI 0.87 to 7.92) (figure 2A). There was no evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity across the studies within the subgroups of China (p=0.452) and Germany (p=0.476). However, significant heterogeneity existed across the studies within the subgroup of Japan (p=0.035).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis of the pooled HRs of overall survival with overexpressed MALAT1 in patients with cancer

| Subgroup analysis | No. of studies | No. of patients | Pooled HR (95% CI) |

Meta-regression (p value) | Heterogeneity (random) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | Random | I2 (%) | p Value | ||||

| Region | |||||||

| China | 9 | 845 | 2.03 (1.61 to 2.56) | 2.03 (1.22 to 2.56) | 0.442* | 0.00 | 0.452 |

| Japan | 3 | 236 | 1.88 (1.20 to 2.96) | 2.62 (0.72 to 2.38) | 0.517* | 70.20 | 0.035 |

| Germany | 2 | 292 | 1.62 (1.06 to 2.47) | 1.62 (1.06 to 2.47) | 0.00 | 0.476 | |

| Sample size | |||||||

| ≥100 | 7 | 980 | 2.04 (1.64 to 2.55) | 2.04 (1.64 to 2.55) | 0.349 | 0.00 | 0.444 |

| <100 | 7 | 393 | 1.63 (1.15,2.31) | 1.78 (1.12 to 2.80) | 32.40 | 0.181 | |

| Type of cancer | |||||||

| Urinary system | 3 | 251 | 1.87 (1.19 to 2.92) | 2.68 (0.95 to 7.57) | 0.854† | 75.60 | 0.017 |

| Digestive system | 5 | 579 | 2.01 (1.51 to 2.67) | 2.08 (1.48 to 2.92) | 0.895† | 24.40 | 0.259 |

| Respiratory system | 3 | 370 | 1.61 (1.10 to 2.37) | 1.61 (1.10 to 2.37) | 0.473† | 0.00 | 0.774 |

| Other system | 3 | 173 | 2.22 (1.40 to 3.53) | 2.22 (1.40 to 3.53) | 0.00 | 0.747 | |

| Quality score (%) | |||||||

| ≥85 | 7 | 641 | 2.24 (1.72 to 2.91) | 2.24 (1.72 to 2.91) | 0.144 | 0.00 | 0.652 |

| <85 | 7 | 732 | 1.64 (1.26 to 2.13) | 1.70 (1.20 to 2.42) | 33.30 | 0.174 | |

*Versus Germany; †versus other system.

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing the subgroup analyses of the pooled HRs with elevated MALAT1 expression in the different types of cancer. Values of p and I2 and the HRs with their 95% CI of overall survival (OS) were analysed by the factors of country (A), cancer type (B), sample size (C), quality score (D), univariate analysis (E) and multivariate analysis (F). Each study is represented by a triangle; the centre of which denotes the HR with the horizontal lines showing the 95% CIs. The diamond gives the overall HR for combined results of subgroup studies; the centre denotes the HR and the extremities the 95% CIs. Weights are from random-effect (A–D) and fixed-effect (E and F) analyses.

The elevated expression of MALAT1 was found to be significantly associated with poor OS in patients with digestive system malignancies (HR=2.08; 95% CI 1.48 to 2.92), respiratory system carcinoma (HR=1.61; 95% CI 1.10 to 2.37) and other system malignancies (HR=2.22; 95% CI 1.40 to 3.53) and not associated with urinary system carcinoma (HR=2.68; 95% CI 0.95 to 7.57) (figure 2B). There was no evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity within the subgroups of patients with digestive system malignancy (p=0.259), respiratory system carcinoma (p=0.774) and other system malignancies (p=0.747). However, a significant heterogeneity was found among the studies of urinary system carcinoma (p=0.017).

It is important to note that the sample size did not alter the predictive value of MALAT1 on the OS for all investigated cancers since the association of MALAT1 with the OS of patients was found to be similar for sample sizes greater than or less than 100 subjects (HR=2.04; 95% CI 1.64 to 2.55 and HR=1.78; 95% CI 1.12 to 2.80, respectively) and no evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity was found among those studies (p=0.444 and p=0.181, respectively) (figure 2C).

Next, we examined the quality of the published paper in the studies and found that the scores (more or less than 85%) did not change the result of the estimated HR (HR=2.24; 95% CI 1.72 to 2.91 and HR=1.70; 95% CI 1.20 to 2.42, respectively) and that there was no evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity across the studies within the subgroups with scores of more or less than 85% (p=0.652 and p=0.174, respectively) (figure 2D).

Using different methods of analysis, we obtained similar results for the association of MALAT1 expression with OS with univariate analysis (HR=1.90; 95% CI 1.60 to 2.25) (figure 2E) and multivariate analysis (HR=1.98; 95% CI 1.60 to 2.46) (figure 2F). No evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity was found across the studies (p=0.123 by univariate analysis and p=0.078 by multivariate analyses).

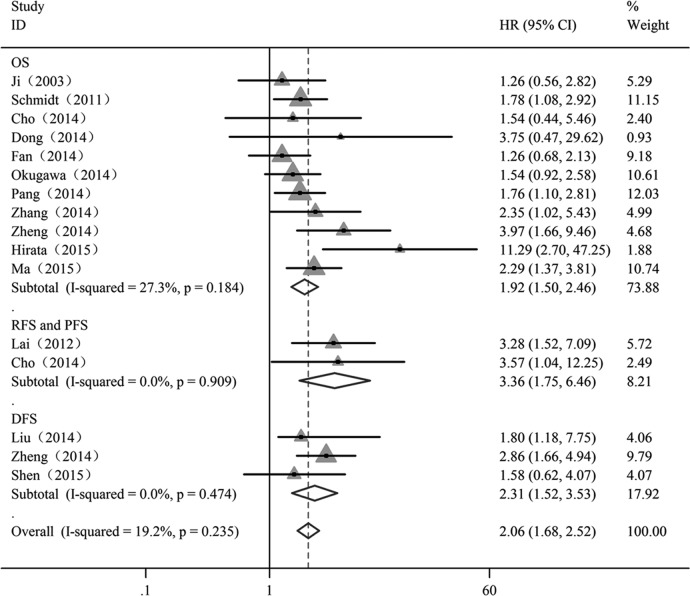

Subsequently, we investigated whether MALAT1 was predictive for the survival (OS, DFS, RFS and PFS) of patients with cancer. Overall analyses of these combined HRs suggested that MALAT1 expression may be an independent prognostic factor for patients with cancer (HR=2.06; 95% CI 1.68 to 2.52), and no evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity was detected across the studies (I2=19.2%; p=0.235) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing meta-analysis of the independent role of MALAT1 on overall survival (OS), recurrence-free survival (RFS)/progression-free survival (PFS) and disease-free survival (DFS) in the different types of cancer. Each study is represented by a triangle; the centre of which denotes the HR with the horizontal lines showing the 95% CIs. The diamond gives the overall HR for combined results of subgroup studies; the centre denotes the HR and the extremities the 95% CIs. Weights are from random-effect analyses.

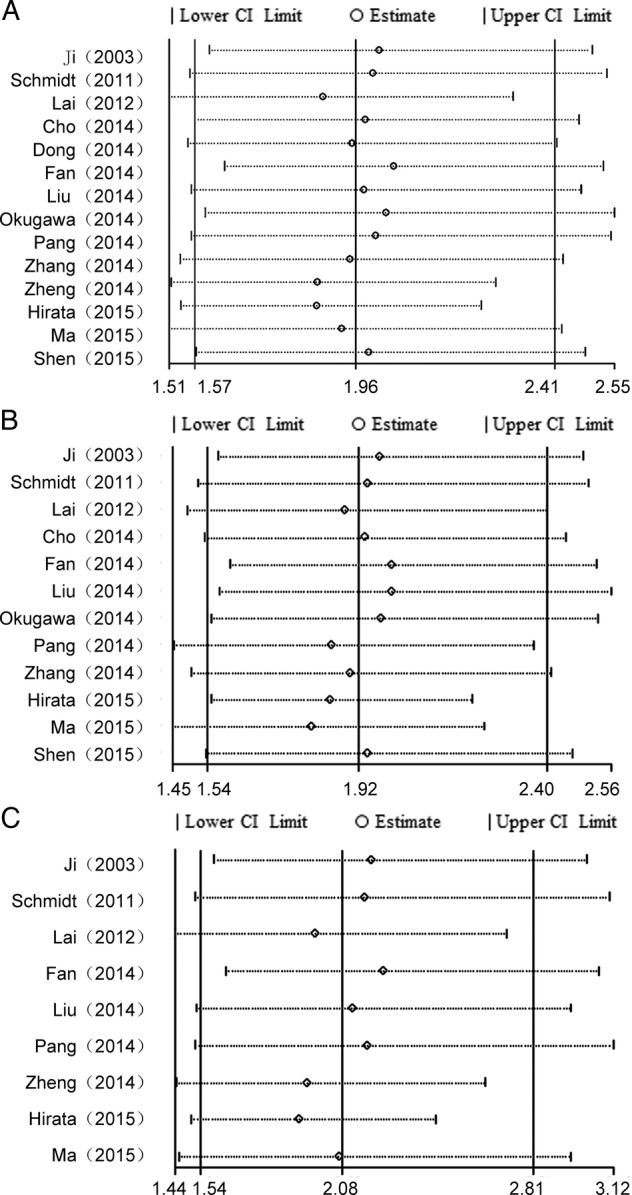

Analysis of sensitivity and publication bias

A meta-regression was applied to quantify the heterogeneity among the covariates, including region, sample size, the type of cancer and paper quality (table 2). We found that there was no specific factor accounting for the interstudy heterogeneity which was consistent with the results of the subgroup analysis. Moreover, the sensitivity analyses showed that the pooled HRs of OS were reliable (figure 4). The exclusion of any individual study did not change the significance of the HRs. The results of sensitivity analyses were similar between those included data and excluded data obtained from Kaplan–Meier curves (see online supplementary information).

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of the individual study on the pooled HRs for the correlation between MALAT1 expression and overall survival (OS) in patients with cancer by univariate and multivariate analyses. (A) Sensitivity analysis of the effect of the individual study on the pooled HRs of OS in the different types of cancer with MALAT1 overexpression. (B) Sensitivity analysis of the effect of the individual study on the independent role of MALAT1 on OS in the different types of cancer by univariate analysis. (C) Sensitivity analysis of the effect of the individual study on the independent role of MALAT-1 on OS in the different types of cancer by multivariate analysis.

To illustrate the heterogeneity across the studies for the independent role of MALAT1 on OS of patients with cancer, subgroup analyses of meta-regression were performed. We found that MALAT1 was an independent factor of prognosis among patients with cancer in China and Germany (table 3). The score of the paper quality and the sample size did not affect the overall results. None of the factors examined, including country (except Japan), sample size, type of cancer (except urinary carcinomas) and paper quality, were responsible for the heterogeneity across the studies in meta-regression.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the independent role of MALAT1 on OS, DFS, RFS and PFS in the different types of cancer

| Subgroup analysis | No. of studies | No. of patients | Pooled HR (95% CI) |

Meta-regression (p value) |

Heterogeneity (random) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | Random | I2 (%) | p Value | ||||

| Overall survival | 11 | 1138 | 1.87 (1.57 to 2.28) | 1.92 (1.50 to 2.46) | – | 27.30 | 0.184 |

| Region | |||||||

| China | 6 | 610 | 1.97 (1.52 to 2.57) | 2.00 (1.49 to 2.70) | 0.513 | 15.90 | 0.312 |

| Japan | 3 | 236 | 1.88 (1.20 to 2.96) | 2.62 (0.87 to 7.92) | 0.582 | 70.20 | 0.035 |

| Germany | 2 | 292 | 1.62 (1.06 to 2.47) | 1.62 (1.06 to 2.47) | 0.00 | 0.476 | |

| Sample | |||||||

| ≥100 | 6 | 868 | 1.96 (1.56 to 2.47) | 1.96 (1.56 to 2.47) | 0.511 | 0.00 | 0.514 |

| <100 | 5 | 270 | 1.61 (1.07 to 2.42) | 2.01 (0.99 to 4.08) | 54.70 | 0.066 | |

| Type of cancer | |||||||

| Digestive system | 3 | 422 | 1.87 (1.35 to 2.58) | 1.96 (1.26 to 3.07) | 0.895 | 24.40 | 0.259 |

| Urinary system | 3 | 251 | 1.87 (1.19 to 2.92) | 2.68 (0.95 to 7.57) | 0.990 | 75.60 | 0.017 |

| Respiratory system | 2 | 292 | 1.62 (1.06 to 2.47) | 1.62 (1.06 to 2.47) | 0.537 | 0.00 | 0.476 |

| Other system | 3 | 173 | 2.22 (1.40 to 3.53) | 2.22 (1.40 to 3.53) | 0.00 | 0.747 | |

| Quality score (%) | |||||||

| ≥85.0 | 6 | 563 | 2.16 (1.61 to 2.89) | 2.16 (1.61 to 2.89) | 0.275 | 0.00 | 0.562 |

| <85.0 | 5 | 575 | 1.64 (1.25 to 2.16) | 1.75 (1.16 to 2.63) | 44.40 | 0.110 | |

| DFS | 3 | 148 | 2.31 (1.52 to 3.53) | 2.31 (1.52 to 3.53) | – | 0.00 | 0.474 |

| RFS and PFS | 2 | 269 | 3.36 (1.75 to 6.46) | 3.36 (1.75 to 6.46) | – | 0.00 | 0.909 |

DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

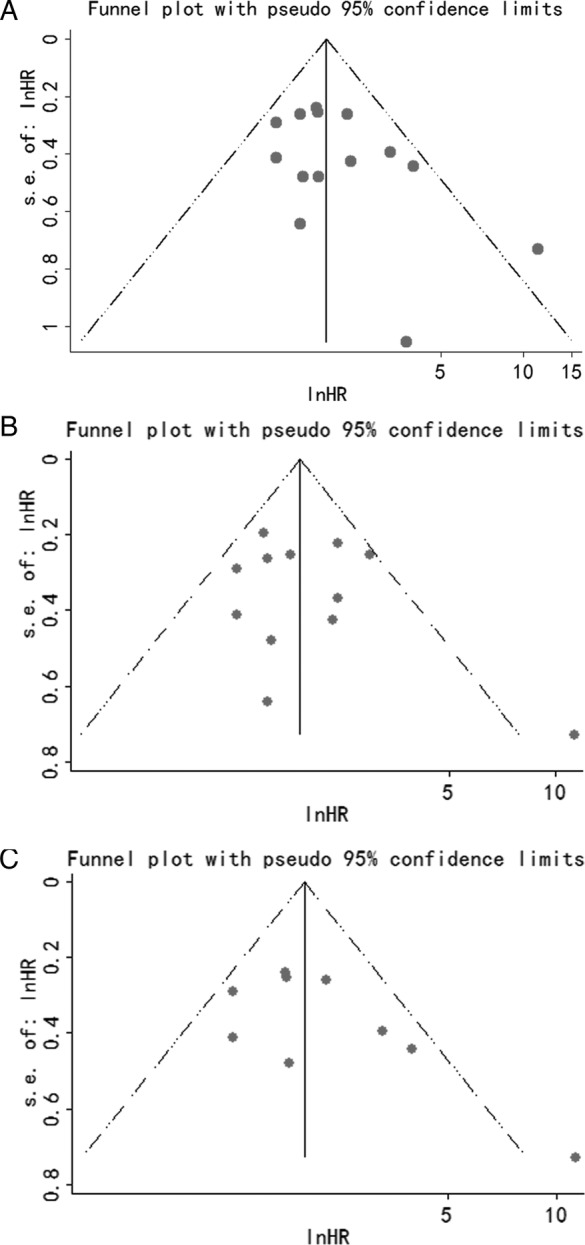

Next, a Begg's funnel plot and Egger's linear regression test were conducted to evaluate publication bias. The funnel plot showed that there was no significant asymmetry, such as the association of MALAT1 expression with OS (figure 5A) and the independent prognostic role of MALAT1 in different types of cancer by univariate analysis (figure 5B) and by multivariate analysis (figure 5C). Subsequently, Egger's linear regression test also proved that there was no evidence of publication bias (p=0.1; p=0.4; p=0.1, respectively).

Figure 5.

Analysis of the correlation between MALAT1 expression and overall survival (OS) in patients with cancer by univariate and multivariate analyses. (A) Funnel plot of the publication bias for the analysis of the pooled HRs of OS in the different types of cancer with MALAT1 overexpression. (B) Funnel plot of the publication bias for the analysis of the independent role of MALAT1 on OS in the different types of cancer by univariate analysis. (C) Funnel plot of the publication bias for the analysis of the independent role of MALAT-1 on OS in the different types of cancer by multivariate analysis.

Discussion

This study disclosed the prognostic value of MALAT1, an important lncRNA involved in cancer metastasis and progression. This meta-analysis of published clinical studies, using a detailed search strategy and predetermined selection criteria, provided convincing evidence that MALAT1 expression is predictive of poor patient survival in various types of cancer.

It has been shown that lncRNAs play important roles in pathophysiological processes. An increasing number of studies showing the involvement of lncRNAs in the development and the progression of various tumours have drawn attention towards these RNA species. MALAT1, one of the lncRNAs, has been shown to be aberrantly expressed in different types of cancer, such as myeloma, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal and pancreatic cancers, etc,17 38 43 44 indicating that MALAT1 may play a role in tumorigenesis. Our meta-analysis summarised the tumour prognostic role of MALAT1 and provided sufficient evidence for the association between MALAT1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics of human cancers, suggesting that MALAT1 may be used as a negative, unfavourable prognostic marker for most cancers.

We examined 14 independent studies comprising data from 1373 patients with similar HRs among various subgroups and using similar analytical methods, and found a reciprocal relationship between elevated MALAT1 expression and OS. Subgroup analyses, including region (China and Germany), cancer type (digestive system carcinoma, respiratory system carcinoma or other system carcinoma), sample size (more or less than 100 patients) and paper quality (with a score of more or less than 85%), showed that these factors did not alter the predictive value of MALAT1 on OS among the investigated cancers. Using Cox multivariate analyses, we also found that MALAT1 was an independent prognostic marker for these carcinomas and no evidence of statistically significant heterogeneity existed across the studies. Furthermore, both Begg's test and Egger's test showed no significant publication bias concerning the independent prognostic role of MALAT1 in the different types of cancer. Therefore, this meta-analysis supports the outcomes of many studies which found that MALAT1 is a molecular predictor of OS.

The prognostic significance of MALAT1 in DFS was evaluated in three studies with 269 patients.22 35 37 Subgroup analysis showed that patients with a high level of MALAT1 were more likely to have significantly shorter DFS. Additionally, the studies included in our analysis also showed the prognostic value of MALAT1 in tumour recurrence and progression. Previous studies have shown that MALAT1 is an independent prognostic factor for predicting the recurrence of HCC and the progression of multiple myeloma,36 43 further supporting our conclusion that MALAT1 is an independent prognostic factor for patient survival.

Recently, the function and role of MALAT1 in tumorigenesis has been extensively investigated. MALAT1 has been shown to promote malignancy as its knockdown inhibits the osteosarcoma cell proliferation and invasion and suppresses metastasis in vivo and in vitro.42 Another study in renal cell carcinoma similarly reported that silencing of MALAT1 reduces cell proliferation and invasion of renal cell carcinoma and increases apoptosis.39 Furthermore, blocking of MALAT1 with antisense oligonucleotides prevents metastasis after tumour implantation in mice.45 Genetic ablation of MALAT1 inhibits endothelial cell proliferation and reduces neonatal retina vascularisation.46 However, MALAT1-knockout mice are viable and fertile and the genetic loss of MALAT1 in mice neither altered cell viability, nor changed apparent phenotypes and/or histology compared with wild-type animals.47 48 MALAT1 is highly evolutionarily conserved in mammals. The upregulation of MALAT1 was mediated by Sp1 at transcription.49 In human cells, MALAT1 induces cellular proliferation by regulating the expression and pre-mRNA processing of cell cycle-related transcription factors. Silencing of MALAT1 by miR-101 and miR-217 can inhibit carcinoma cell proliferation, migration and invasion.50 Depletion of MALAT1 leads to the activation of p53 and its downstream target genes.51 Furthermore, knockdown of MALAT1 inactivates the ERK/MAPK pathway in gallbladder carcinoma cell lines.19 Based on these studies and owing to its functions, MALAT1 may be a consequential biomarker, and also be one of the causal factors for tumorigenesis in general.

As with any meta-analysis our analysis has a few limitations due to the discrete data across these clinical studies. For example, the criteria for calculating the cut-off value were not the same in different studies. The inclusion of a relatively small number of studies in different regions (China, Japan and Germany) might have decreased the applicability of our results across different ethnicities. In this meta-analysis, only summarised data rather than individual patient data were used. Furthermore, some of the HRs were calculated by reconstructing survival curves rather than directly obtained from the primary studies. The data collection may be incomplete because data from non-English language papers were not included. Therefore, it is possible that our results might overestimate the predictive significance of MALAT1 in the prognosis of patients with cancer. We believe that more clinical studies should be conducted to evaluate the prognostic potential of MALAT1 in other types of cancer that have not been included.

In summary, this meta-analysis shows that elevated MALAT1 expression is common to various types of cancer and that it is significantly associated with the poor OS. Furthermore, the functional role of MALAT1 in the regulation of cell proliferation, apoptosis and metastasis suggests that MALAT1 may play a key role in tumour progression. Thus, MALAT1 may potentially be used as a new prognostic marker to predict the OS and tumour recurrence of patients with cancer. More clinical studies on the different types of human cancer that have not yet been investigated need to be conducted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr L Nadeem (Lunenfeld Tanenbaum Research Institute, University of Toronto, Canada) for critical review and professional editing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: XT and GX conceived and designed the study, collected the data, performed the data extraction, conducted the quality assessment, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81272880), the Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology (124119b1300) and Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau (2012–186) to GX. XT was recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from Fudan University and Jinshan Hospital.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Cech TR, Steitz JA. The noncoding RNA revolution-trashing old rules to forge new ones. Cell 2014;157:77–94. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holoch D, Moazed D. RNA-mediated epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat Rev Genet 2015;16:71–84. 10.1038/nrg3863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geisler S, Coller J. RNA in unexpected places: long non-coding RNA functions in diverse cellular contexts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2013;14:699–712. 10.1038/nrm3679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ørom UA, Shiekhattar R. Long noncoding RNAs usher in a new era in the biology of enhancers. Cell 2013;154:1190–3. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akrami R, Jacobsen A, Hoell J et al. Comprehensive analysis of long non-coding RNAs in ovarian cancer reveals global patterns and targeted DNA amplification. PLoS One 2013;8:e80306 10.1371/journal.pone.0080306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han D, Wang M, Ma N et al. Long noncoding RNAs: novel players in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett 2015;361:13–21. 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng N, Li X, Zhao C et al. Microarray expression profile of long non-coding RNAs in EGFR-TKIs resistance of human non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep 2015;33:833–9. 10.3892/or.2014.3643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu W, Gao T, Sun Y et al. LncRNA expression profile reveals the potential role of lncRNAs in gastric carcinogenesis. Cancer Biomark 2015;15:249–58. 10.3233/CBM-150460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang JL, Zheng L, Hu YW et al. Characteristics of long non-coding RNA and its relation to hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2014;35:507–14. 10.1093/carcin/bgt405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Augoff K, McCue B, Plow EF et al. miR-31 and its host gene lncRNA LOC554202 are regulated by promoter hypermethylation in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer 2012;11:5 10.1186/1476-4598-11-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer 2011;10:38 10.1186/1476-4598-10-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loewen G, Jayawickramarajah J, Zhuo Y et al. Functions of lncRNA HOTAIR in lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2014;7:90 10.1186/s13045-014-0090-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iguchi T, Uchi R, Nambara S et al. A long noncoding RNA, lncRNA-ATB, is involved in the progression and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res 2015;35:1385–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Z, Fei T, Verhaak RG et al. Integrative genomic analyses reveal clinically relevant long noncoding RNAs in human cancer. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2013;20:908–13. 10.1038/nsmb.2591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji P, Diederichs S, Wang W et al. MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA and thymosin beta4 predict metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2003;22:8031–41. 10.1038/sj.onc.1206928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Diederichs S. MALAT1—a paradigm for long noncoding RNA function in cancer. J Mol Med 2013;91:791–801. 10.1007/s00109-013-1028-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu L, Wu Y, Tan D et al. Up-regulation of long noncoding RNA MALAT1 contributes to proliferation and metastasis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015;34:7 10.1186/s13046-015-0123-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma KX, Wang HJ, Li XR et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 associates with the malignant status and poor prognosis in glioma. Tumour Biol 2015;36:3355–9. 10.1007/s13277-014-2969-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu XS, Wang XA, Wu WG et al. MALAT1 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of gallbladder cancer cells by activating the ERK/MAPK pathway. Cancer Biol Ther 2014;15:806–14. 10.4161/cbt.28584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ying L, Chen Q, Wang Y et al. Upregulated MALAT-1 contributes to bladder cancer cell migration by inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Mol Biosyst 2012;8:2289–94. 10.1039/c2mb25070e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okugawa Y, Toiyama Y, Hur K et al. Metastasis-associated long non-coding RNA drives gastric cancer development and promotes peritoneal metastasis. Carcinogenesis 2014;35:2731–9. 10.1093/carcin/bgu200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng HT, Shi DB, Wang YW et al. High expression of lncRNA MALAT1 suggests a biomarker of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2014;7:3174–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji Q, Zhang L, Liu X et al. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 promotes tumour growth and metastasis in colorectal cancer through binding to SFPQ and releasing oncogene PTBP2 from SFPQ/PTBP2 complex. Br J Cancer 2014;111:736–48. 10.1038/bjc.2014.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt LH, Spieker T, Koschmieder S et al. The long noncoding MALAT-1 RNA indicates a poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer and induces migration and tumor growth. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:1984–92. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182307eac [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W. Identification of clinically useful cancer prognostic factors: what are we missing? J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:1023–5. 10.1093/jnci/dji193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman DG, McShane LM, Sauerbrei W et al. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. BMC Med 2012;10:51 10.1186/1741-7015-10-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W et al. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK). J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:1180–4. 10.1093/jnci/dji237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steels E, Paesmans M, Berghmans T et al. Role of p53 as a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2001;18:705–19. 10.1183/09031936.01.00062201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xing X, Tang YB, Yuan G et al. The prognostic value of E-cadherin in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2013;132:2589–96. 10.1002/ijc.27947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D et al. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007;8:16 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998;17:2815–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shen L, Chen L, Wang Y et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes brain metastasis by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung cancer. J Neurooncol 2015;121:101–8. 10.1007/s11060-014-1613-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lai MC, Yang Z, Zhou L et al. Long non-coding RNA MALAT-1 overexpression predicts tumor recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Med Oncol 2012;29:1810–16. 10.1007/s12032-011-0004-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu JH, Chen G, Dang YW et al. Expression and prognostic significance of lncRNA MALAT1 in pancreatic cancer tissues. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:2971–7. 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.7.2971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang EJ, Yang R, Fu XB et al. Overexpression of long non-coding RNA MALAT1 is correlated with clinical progression and unfavorable prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Tumour Biol 2015;36:2403–7. 10.1007/s13277-014-2850-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirata H, Hinoda Y, Shahryari V et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 promotes aggressive renal cell carcinoma through Ezh2 and interacts with miR-205. Cancer Res 2015;75:1322–31. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang HM, Yang FQ, Chen SJ et al. Upregulation of long non-coding RNA MALAT1 correlates with tumor progression and poor prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol 2015;36:2947–55. 10.1007/s13277-014-2925-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fan Y, Shen B, Tan M et al. TGF-beta-induced upregulation of malat1 promotes bladder cancer metastasis by associating with suz12. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:1531–41. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong Y, Liang G, Yuan B et al. MALAT1 promotes the proliferation and metastasis of osteosarcoma cells by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway. Tumour Biol 2015;36:1477–86. 10.1007/s13277-014-2631-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho SF, Chang YC, Chang CS et al. MALAT1 long non-coding RNA is overexpressed in multiple myeloma and may serve as a marker to predict disease progression. BMC Cancer 2014;14:809 10.1186/1471-2407-14-809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang MH, Hu ZY, Xu C et al. MALAT1 promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation/migration/invasion via PRKA kinase anchor protein 9. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015;1852:166–74. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gutschner T, Hämmerle M, Eissmann M et al. The noncoding RNA MALAT1 is a critical regulator of the metastasis phenotype of lung cancer cells. Cancer Res 2013;73:1180–9. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michalik KM, You X, Manavski Y et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates endothelial cell function and vessel growth. Circ Res 2014;114:1389–97. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eißmann M, Gutschner T, Hämmerle M et al. Loss of the abundant nuclear non-coding RNA MALAT1 is compatible with life and development. RNA Biol 2012;9:1076–87. 10.4161/rna.21089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakagawa S, Ip JY, Shioi G et al. Malat1 is not an essential component of nuclear speckles in mice. RNA 2012;18:1487–99. 10.1261/rna.033217.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li S, Wang Q, Qiang Q et al. Sp1-mediated transcriptional regulation of MALAT1 plays a critical role in tumor. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015;141:1909–20. 10.1007/s00432-015-1951-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, Li M, Wang Z et al. Silencing of long noncoding RNA MALAT1 by miR-101 and miR-217 inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 2015;290:3925–35. 10.1074/jbc.M114.596866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tripathi V, Shen Z, Chakraborty A et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 controls cell cycle progression by regulating the expression of oncogenic transcription factor B-MYB. PLoS Genet 2013;9:e1003368 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]