Abstract

Gloves are often needed for hand protection at work, but they can impair manual dexterity, especially if they are multilayered or ill-fitting. This article describes two studies of gloves to be worn with airfed suits (AFS) for nuclear decommissioning or containment level 4 (CL4) microbiological work. Both sets of workers wear multiple layers of gloves for protection and to accommodate decontamination procedures. Nuclear workers are also often required to wear cut-resistant gloves as an extra layer of protection. A total of 15 subjects volunteered to take part in manual dexterity testing of the different gloving systems. The subjects’ hands were measured to ensure that the appropriate sized gloves were used. The gloves were tested with the subjects wearing the complete clothing ensembles appropriate to the work, using a combination of standard dexterity tests: the nine-hole peg test; a pin test adapted from the European Standard for protective gloves, the Purdue Pegboard test, and the Minnesota turning test. Specialized tests such as a hand tool test were used to test nuclear gloves, and laboratory-type manipulation tasks were used to test CL4 gloves. Subjective assessments of temperature sensation and skin wettedness were made before and after the dexterity tests of the nuclear gloves only. During all assessments, we made observations and questioned the subjects about ergonomic issues related to the clothing ensembles. Overall, the results show that the greater the thickness of the gloves and the number of layers the more the levels of manual dexterity performance are degraded. The nuclear cut-resistant gloves with the worst level of dexterity were stiff and inflexible and the subjects experienced problems picking up small items and bending their hands. The work also highlighted other factors that affect manual dexterity performance, including proper sizing, interactions with the other garments worn at the time, and the work equipment in use. In conclusion, when evaluating gloves for use in the workplace it is important to use tests that reflect the working environment and always to consider the balance between protection and usability.

KEY WORDS: containment, cut-resistant gloves, decommissioning, decontamination, dexterity, interaction, protective gloves, workplace

INTRODUCTION

Workers are often required to wear gloves in the workplace to protect their hands from hazards such as cuts and contamination with hazardous chemicals or microbiological pathogens. However, the functions of the bare hand (BH) such as touch sensitivity and the ability to manipulate objects can be impaired by wearing bulky or multiple layers of gloves. In general, the thinner the glove the less it impairs manual dexterity (Bensel, 1993). The thickness of each layer of gloves is important to the overall bulk of the glove assembly.

Movement of the hand, tactile sensation, and grip can all be reduced by ill-fitting gloves (O’Hara, 1989; Drabeck et al., 2009). If they are too large, excess material gathers and folds, increasing bulk. If they are too small, they can constrict the hand and restrict movement. Gloves designed with seams positioned round the finger joints create increased bulk and stiffness (Muralidhar et al.,1999). Because of these effects, it is therefore important to ensure that the size and thickness of the glove, the type of material, and the construction used are optimized to the level of protection required by the individual user.

The anatomical structure of the hand is adapted to the gripping of objects. The tight skin on the palmar side of the hand adheres to the underlying anatomical structures and remains in place, giving stability when gripping objects. The fatty pads on the finger tips deform and flatten when gripping, which increases the surface contact area to enable the object to be held firmly in place. The skin on the back of the hand and fingers is loose and bends easily which allows the fingers to bend unhindered and perform fine movements (Vanggaard, 2007).

Ideally, gloves should fit the hand well, allowing the hand to rest in the relaxed position with the fingers slightly curved towards the palm. According to Vanggaard (2007), the best gloves will imitate the anatomy of the hand and should be an extension of the skin, with the material on the palm pulled taut and thin enough to allow the transmission of tactile information from the object to the skin touch sensors, aiding grip through sensory feedback. The materials on the back of the hand should be loose enough to allow the full range of movements.

If the skin of the hands is soaked in sweat, or water that has penetrated the glove, the epidermis of the skin swells and softens and this maceration makes fine movements and grip more difficult. To counteract this, gloves should also be designed to keep the hands dry by allowing the evaporation of sweat, and preventing the penetration of environmental water.

When considering the design of a clothing system the sleeve should interface well with the glove system ensuring protection, but also ease of movement of the arm and hand. Ill-fitting sleeves or cumbersome glove attachment systems can also affect dexterity by restricting movement and making the glove ensemble more bulky. This article describes studies of gloves worn with two types of airfed suits (AFS) for nuclear decommissioning (ND) work, and glove systems for microbiological containment level 4 (CL4) work including the use of AFS. While the AFS for nuclear and CL4 applications differ in details of their design and construction, they all comprise a fully encapsulating impermeable envelope into which air is supplied at a rate of ~180 l min−1, with excess air venting to atmosphere through exhaust valves. Suits may be one- or two-piece, designed for single use or to be reusable after decontamination and servicing.

Nuclear decommissioning workers wear several layers of gloves to protect their hands from radioactively contaminated dust in the containment area and to aid safe undressing and decontamination. Once in the contaminated area workers are often required to cut and handle sharp-edged pieces of metal and therefore need to wear extra cut-resistant gloves over the top of their multilayered glove system. This part of the study was to compare the dexterity and usability of a range of different cut-resistant gloves used in conjunction with AFS for ND.

CL4 AFS workers are required to work within microbiological safety cabinets and on open bench tops in AFS, rather than in conventional laboratory wear using glove boxes. All CL4 workers whether in AFS or in conventional laboratory wear are required to wear two pairs of gloves according to site standard operating procedures. For those in the AFS, one pair is integrated into the AFS, and for those in conventional laboratory wear a pair of gloves is integrated into the glove box. This part of the study was to compare the practicalities of the AFS and glove box approaches to working.

Gloves for the workplace need to be selected with care and should depend on the protection required, the work environment, tasks to be completed, and the population that requires hand protection. For both nuclear and CL4 workers, it is important that the gloves they use to protect themselves do not degrade their performance so that they are able to complete the required tasks in their respective potentially hazardous environments safely. When evaluating the gloves it is important that real life situations are considered. Dianat et al. (2012) recommended that tests and tasks should match the workplace requirements as closely as possible, preferably mimicking actual tasks in a manner that can be assessed quantitatively.

The purpose of this study was to assess the best gloves for use in the workplace using standardized tests chosen to mimic these typical work place requirements for either gross movement or fine finger dexterity. In a broader context, the value of the work is as an example case study in demonstrating a process by which gloves can be practically assessed using a test battery tailored to specific working applications.

METHODS

Prior to deciding what manual dexterity tests should be used in the experimental testing protocol, we observed and interviewed both the nuclear and CL4 glove users. This was a key step in choosing dexterity and functionality tests that were the most appropriate to the applications for which the protective glove systems were required. We observed that ND workers found it difficult to work with small hand tools and undo nuts and bolts. This led to poor compliance with written site operational procedures through removal of the cut-resistant gloves so they could perform or complete fine finger dexterity tasks. CL4 workers were required to carry out, accurately and precisely, work which required a high degree of fine manual dexterity, such as pipetting, serial dilutions and microtitre plating tasks.

Seven male subjects volunteered to take part in the testing of cut-resistant gloves for ND and five males and three females volunteered for the CL4 glove assessments. The experimental protocols were approved by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Research Ethics Committee. The subjects were medically screened and gave informed consent to take part in the experiments.

As the layered glove systems are part of an ensemble and interface with the AFS, the gloves were tested with the subjects wearing one of the impermeable, full AFS ensembles. For ND glove system testing, the subjects wore either a disposable two piece (ND 2-piece) or reusable one piece (ND 1-piece) AFS. The interfaces between the glove and the suit were different for the two suits; on ND 2-piece, the AFS sleeve was tied down close to the subject’s wrist with the glove pulled over the top, and with ND 1-piece, the gloves were pulled over a rigid ring situated on the end of the AFS sleeve. The subjects wore standard cotton long sleeved and long legged underwear plus socks and Wellington boots with both types of AFS. The ND 1-piece AFS was worn with two additional oversuits and overhoods; the ND 2-piece had only one additional oversuit and no overhood. In the ND 1-piece suit, the breathing and ‘cooling’ air entered the suit through a halo in the hood, and via a valve situated at the front lower portion of the hood for the ND 2-piece suit.

The circumference and length of the dominant hand of each subject were measured to ensure that the subjects were fitted with the correct base glove size according to the sizing classification of BS EN 420:2003 (BSI, 2003b). Multiple glove systems were carefully fitted over the top of the base glove to minimize bulk. The thickness of the base layers of gloves worn underneath the BS EN 388 (BSI, 2003a) cut-resistant glove dictated the size of cut-resistant glove that could be fitted. The bulkier layers of AFS ND 1-piece meant that larger cut-resistant glove sizes had to be worn than in AFS ND 2-piece.

For the AFS CL4 glove assessments on the bench top and in the safety cabinet, the subjects wore underwear, socks, and surgical scrubs (trousers and long sleeved top) underneath a one piece reusable AFS worn with Wellington boots. The subjects wore nitrile gloves over the AFS gloves which were attached to the suit. For the non-AFS CL4 testing with the microbiological glove box, the subjects wore surgical scrubs and a laboratory coat with nitrile gloves inside the glove box integral gloves. The gloves worn with the nuclear and CL4 AFS and with the CL4 laboratory wear are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Glove systems used for nuclear decommissioning (ND 2-piece and ND 1-piece AFS) and CL4 work (in laboratory wear or AFS).

| Worn with: | Nuclear decommissioning glove layers | CL4 glove layers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ND 2-piece AFS | ND1-piece AFS | Laboratory wear | AFS | |

| First layer | Sockinette | Sockinette | 0.15mm nitrile examination glove | 0.74mm neoprene with cotton flock lining (AFS integral glove) |

| Second layer | 0.50mm thick latex, unlined | 0.40mm thick nitrile (AFS integral glove) | 0.59mm unlined neoprene (Glove box integral glove) | 0.15mm nitrile examination glove |

| Third layer | 0.50mm thick latex, unlined | 0.73mm thick latex with cotton flock lining | ||

| Fourth layer | 0.50mm thick latex, unlined | 0.73mm thick latex with cotton flock lining | ||

| Fifth layer | Cut-resistant conforming to BS EN 388 (BSI, 2003) | |||

| Type A: Knitted liner with foamed nitrile coating | ||||

| Type B: Knitted Acrylic liner with textured latex palm and fingers | ||||

| Type C: Woven cotton liner with nitrile/knitted textile outer | ||||

The ND and the CL4 glove testing were treated as two separate experiments, but within each protocol, the gloves were worn and the conditions changed according to a randomized Latin square design to eliminate any systematic effects of testing order. The manual dexterity tests took place at temperatures between 18 to 21ºC in the Health and Safety Laboratory (HSL) thermal chamber or an air conditioned laboratory to ensure that the heavily clothed subjects did not suffer undue thermal stress.

Prior to the commencement of these tests, the subjects were trained on all the dexterity tests, practicing without gloves [bare hands (BH)] until a plateau time had been reached. Each test was then repeated three times and the mean performance (e.g. time to complete, or number of pegs placed depending on the test) recorded as the BH score against which gloved hand performance was later assessed.

The gloves were assessed with a mixture of standard dexterity tests, selected to correspond with the work place requirements (nine-hole peg test; modified BS EN 420 pin test (BSI, 2003b); Purdue Pegboard test; Minnesota turning test), and specialized tests designed around either nuclear or CL4 work tasks. For the nuclear gloves, a hand tool test was used, and for the CL4 gloves, specific laboratory type tasks (pipetting, microtitre plate and serial dilution tasks) were used. All gloves were new at the start of the experiments.

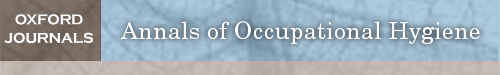

The nine-hole peg test (Rolyan Model A8515, see Fig. 1) is a measure of gross movement of the fingers, hands and arms and of finger dexterity. It has a large cup containing nine nylon pegs (diameter 6mm, length 30mm), and a 3×3 square array of sockets spaced 30mm apart. The time for the subject to place all the pegs in the pegboard in a set order, first with the preferred hand and then the other hand was measured three times. With the right hand, the subject placed pegs moving from right to left across the top of the board, left to right across the middle row and right to left across the bottom row. With the left hand the subject placed pegs in to the pegboard moving from left to right across the top of the board, right to left across the middle row and left to right across the bottom row (Mathiowetz et al., 1985).

Figure 1.

Nine-hole peg test being carried out in AFS ND 2-piece with cut-resistant glove A.

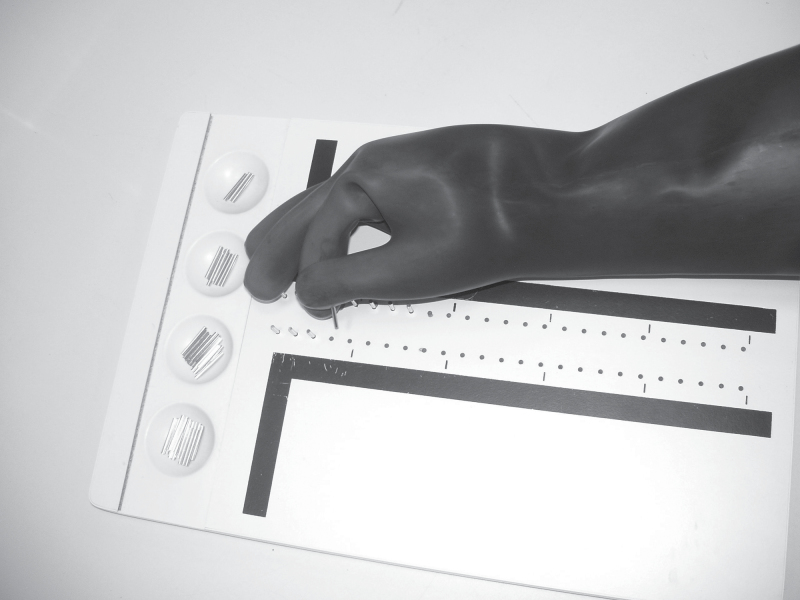

The Purdue Pegboard (Lafayette Instrument Model #32020) has two parallel rows of pinhole sockets down the centre of the board (Fig. 2). The steel pins of diameter 2.5mm and length 25mm were placed in the outer cups at the top of the board. The subject was asked to pick up pins with their right hand one at a time, from the right hand cup, and place them in the right hand side of the pegboard. The subject had to pick up and place as many pins as possible in 30 s. This was then repeated for the left hand, picking up pins from the left hand cup, and placing them in the left hand side of the pegboard. The test is a measure of gross movement of the fingers, hands, and arms together with the fine tasks of assembly (Lafayette Instrument, 1999).

Figure 2.

Purdue Pegboard manual dexterity test.

The Minnesota turning test (Lafayette Instrument Model #32023A) uses a board with 60 holes of 4cm diameter, which are 2cm apart, each containing a black disc which fits loosely into the hole (Fig. 3). The subject worked both ways across the board, picking up each of the discs with their lead hand, turning it over to reveal a red face and replacing it in the same hole with the other hand. This test involves rapid eye-hand co-ordination and arm-hand dexterity (Lafayette Instrument, 1998). The score is given as the time taken to turn all 60 discs. The test was repeated three times to give a mean time.

Figure 3.

Minnesota turning test.

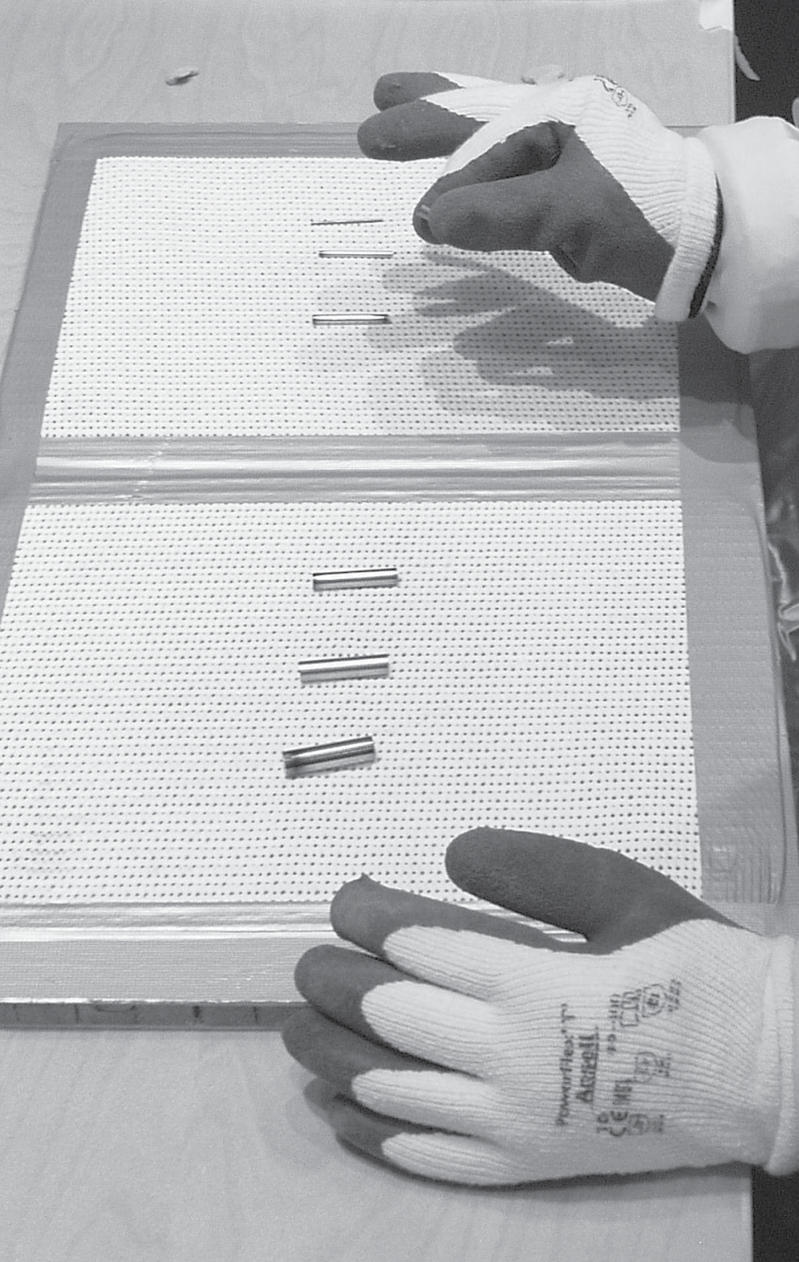

The BS EN 420 pin test (BSI, 2003b) uses five steel pins of decreasing diameter (11, 9.5, 8, 6.5, and 5mm; length 40mm) as illustrated in Fig. 4). In an attempt to increase the discrimination between glove types, HSL has modified the test by adding two smaller pins of 3.5 and 2mm diameter of the same length as the existing pins. The subjects were asked to pick up each pin (largest diameter first) between the thumb and forefinger three times within 30 s. If the subject successfully completed the task, they moved to the next pin size down and repeated the exercise. If they failed to pick up the pin three times within the timeframe, it was deemed a failure and the test was concluded. The measure is the smallest diameter of pin that can be picked up three times within the timeframe. This test assesses the finger dexterity of the gloves and, as the pin sizes reduce in diameter, fine finger dexterity.

Figure 4.

Modified BS EN 420 pin test.

The hand tool dexterity test (Fig. 5) has a wooden frame through which three rows of bolts, nuts, and washers of three different sizes are fitted, with the bolt heads mounted towards the inside of the frame, with a washer either side of the wood (Lafayette Instrument Model 32521). The largest bolts, positioned in the top row, are 73×12mm (length × diameter). The smallest bolts in the bottom row are 65×4mm. The subject first removed all the bolts from the left hand side of the frame on each row starting at the top and working down, a row at a time, to the bottom row. Once the bolts were loosened with the appropriate wrench/screwdriver, the fingers were used to further loosen and remove the bolts. The subject was allowed to select which tools to use to remove each size of bolt but to ensure consistency they had to use the same tool each time the test was repeated. The bolts were then remounted on the right side of the wooden frame starting at the bottom and working up to the top row (with the bolt heads on the inside of the frame). The subject was required to tighten the bolts using tools so they could not be removed with the fingers (Lafayette Instrument, 2002). The score was the time taken to remove and replace all the bolts. The test measures gross movement of the fingers, hands, and arms and fine finger dexterity. It also tests the ability to use simple mechanics’ tools and can be an indicator of success where jobs require the use of these or similar tools.

Figure 5.

Hand tool dexterity test.

Subjective assessments of temperature sensation and skin wettedness were made before and after the dexterity tests of the nuclear decommissioning assessments only. The subjects were asked to use the BS EN ISO 10551 (BSI, 2001) scale to assess how hot or cold their hands and other body parts (e.g. head, torso and legs) felt. They assessed the skin wettedness of these areas using a nine-point scale (Havenith and Heus, 2004). During all assessments, the subjects were observed and questioned on completion of the tests about ergonomic issues with the clothing and gloves and any adverse interactions between the two.

RESULTS

Nuclear decommissioning glove ensembles

Full test results from the two ND gloves systems (ND 2-piece and ND 1-piece) for the three types of cut-resistant glove (A, B, and C) and BH are given in Tables A1 to A4, available as supplementary data at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online. Specific findings of the separate tests are described here and summarized in Table 2 in terms of pairwise comparison rankings for the various cut-resistant glove systems between BH and gloved hand conditions. Statistical differences were calculated, with significance accepted at P < 0.01. The modified BS EN 420:2003 pin test was not included in the ranking process, as the test did not discriminate between gloves A and B. The results show that wearing of any type of glove significantly reduced the performance of the dexterity tasks compared with BHs.

Table 2.

Pairwise comparison ranking of the performance of bare hands versus the glove and nuclear decommissioning AFS for the various manual dexterity tests, significant difference in rankings accepted at P < 0.01.

| Test | Suit | ND 2-piece | ND 1-piece | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glove | A | B | C | A | B | C | |

| Nine-hole peg board test | Preferred handa | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| Nine-hole peg board test | Other handb | 1 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Minnesota turning test | Both handsc | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Hand tool test | Both handsc | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| Mean ranking | 1.0 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 3.3 | 6.0 | |

ND 2-piece and ND 1-piece are different suit/glove base ensembles described in Table 1. BH, bare hands. A, B and C are different outer cut resistant glove models: A: Knitted liner with foamed nitrile coating, B: Knitted Acrylic liner with textured latex palm and fingers, C: Woven cotton liner with nitrile/knitted textile outer.

ai.e. right hand for right-handed volunteers, left hand for left-handed volunteers.

bi.e. left hand for right-handed volunteers, right hand for left-handed volunteers.

cTest requires the use of both hands.

In both AFS types, the subjects performed the nine-hole peg board test (Table A1 is available as supplementary data at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online) quicker, with either hand, when wearing gloves A and B than in glove C. The test had to be halted for two of the subjects wearing cut-resistant glove C and AFS ND 2-piece as they became very frustrated by their inability to perform the task and would have withdrawn from the experiment if the test had not been stopped.

Table A2 is available as supplementary data at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online shows that glove C, when either type of AFS was worn, again performed very poorly in the modified pin test when compared with gloves A and B. The subjects were only able to pick up the larger pins (11–5mm) or in some cases none at all while wearing glove C but were able to pick up the smallest size pin (2mm) while wearing gloves A and B.

In both AFS types, the subjects performed the Minnesota turning test (Table A3 is available as supplementary data at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online) and the hand tool test (Table A4 is available as supplementary data at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online) significantly better in gloves A and B than when wearing glove C. Four subjects failed to complete the Minnesota turning test in glove C. Two failed to complete the hand tool test in AFS ND 2-piece because they became very frustrated by their inability to pick up the nuts and washers. The other two in ND 1-piece took longer than 20min to complete this test. In these two tests, there was little difference between gloves A and B in either AFS.

For each of the glove systems, the subjects were able to perform the manual dexterity tests better when wearing suit ND 2-piece than ND 1-piece. In either AFS, the subjects were able to perform dexterity tests slightly better in cut-resistant glove A than B and both these gloves performed better than glove C.

The subjects wearing ensemble ND 2-piece all rated the temperature sensations of all parts of the body (feet, legs, arms, chest, back, and head) as ‘Neither hot nor cold’, except for the hands which even at the start of the experiment they rated as ‘Slightly warm’. After the dexterity tests had been completed, they rated all parts of the body between ‘Neither hot nor cold’ and ‘Slightly warm’ with the exception of the hands and feet which they rated as ‘Warm’. There was a similar picture at the beginning of the experiment when ND 1-piece was worn. However, after completion of the dexterity tests the subjects rated their temperature sensations between ‘Slightly warm’ and ‘Warm’ but rated their hands as ‘Hot’.

Skin wettedness for subjects wearing both AFS ensembles on entry to the chamber was rated as ‘Dry’ to ‘Slightly moist’ for the body with the hands rated from ‘Slightly moist’ to ‘Moist’. On completion of the dexterity tests, the subjects in the ND 2-piece rated their skin on their body as feeling ‘Dry’ to ‘Slightly moist’ to ‘Moist’ with their hands ‘Moist’ and those wearing the ND 1-piece suit, the skin on their body was rated as ‘Slightly moist’ to ‘Moist’ with their hands rated as ‘Wet’.

Containment level 4 glove systems

Table 3 shows the results of the manual dexterity tests carried out on eight subjects for the CL4 AFS or laboratory wear (LW) at a bench top (BT) or within a glove box (GB) or safety cabinet (SC). The glove systems compared were those for laboratory wear (LW) or AFS, and BH. The means and standard deviations (SD (n − 1)) (where data was normally distributed), or medians and percentiles (25–75th %ile) (where data was not normally distributed) are calculated for each hand/location/glove system condition from the times taken, or number of pegs placed, in three repeat tests carried out by each of the eight subjects (n = 24 data points).

Table 3.

Results from the CL4 manual dexterity tests.

| Nine-hole peg board test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand | Location | Glove system | Time (s) | |

| Median | 25–75th %ile | |||

| Preferreda | BT | BH | 11.5 | 11.1–12.3 |

| GB | LW | 24.4 | 22.5–26.4 | |

| BT | AFS | 27.3 | 22.0–34.4 | |

| SC | AFS | 29.4 | 24.7–36.1 | |

| Otherb | BT | BH | 12.0 | 12.0–12.1 |

| GB | LW | 29.0 | 25.6–31.8 | |

| BT | AFS | 31.4 | 24.8–39.8 | |

| SC | AFS | 38.8 | 23.0–42.7 | |

| Purdue Pegboard test | ||||

| Hand | Location | Glove system | Number of pegs | |

| Mean | SD (n − 1) | |||

| Preferreda | BT | BH | 16.3 | 1.7 |

| GB | LW | 7.8 | 1.6 | |

| BT | AFS | 6.6 | 1.8 | |

| SC | AFS | 6.9 | 1.8 | |

| Otherb | BT | BH | 15.3 | 1.2 |

| GB | LW | 6.7 | 1.1 | |

| BT | AFS | 6.3 | 1.6 | |

| SC | AFS | 6.0 | 1.9 | |

| Minnesota turning test | ||||

| Hand | Location | Glove system | Time (s) | |

| Mean | SD (n − 1) | |||

| Bothc | BT | BH | 21.6 | 3.5 |

| GB | LW | 50.5 | 7.3 | |

| BT | AFS | 49.1 | 10.8 | |

| SC | AFS | 54.3 | 15.2 | |

Locations: BT = Bench top; GB = Glove box; SC = Safety cabinet; Glove systems: BH = Bare hands; LW = with Lab wear; AFS = with airfed suit.

ai.e. right hand for right-handed volunteers, left hand for left-handed volunteers.

bi.e. left hand for right-handed volunteers, right hand for left-handed volunteers.

cTest requires the use of both hands.

In all experimental scenarios, the wearing of CL4 glove systems significantly reduced the performance of the dexterity tasks compared with BHs. The modified pin test results are not reported as all subjects picked up all pins in all glove types and scenarios. The subjects were able to perform the Purdue Pegboard test while wearing the CL4 glove ensembles, as they were much thinner than the nuclear decontamination and cut-resistant glove ensembles.

The performance of subjects wearing CL4 glove systems was better in the nine hole and Purdue Pegboard tests performed in a glove box when wearing laboratory wear, than on either a bench top or in a safety cabinet wearing an AFS. However, this was reversed with the Minnesota turning test on a bench top when the best mean performance was when wearing an AFS (Table 3).

The laboratory manipulation tests showed that not just the gloves affected the manual dexterity ratings. Issues were found with the bad positioning of an air supply valve on the AFS that obscured the vision of the subject and interfered with the reach. The interaction between the AFS and the safety cabinet was poor. The visor of the AFS frequently knocked against the glass shield on the front of the cabinet which caused the user to sit further away from the cabinet, causing reach problems.

DISCUSSION

In their systematic review of published literature on glove evaluation methodology from the 43 years prior to the publication of their article, Dianat et al. (2012) identify 11 articles related to glove assessment in conjunction with applications needing the use of suited systems. The majority of these (eight) involve spacesuits for extra vehicular activity, with the remainder involving diving or military chemical/biological/nuclear protection suits. None relate to the type of AFS/glove systems considered in this work.

Our results showed that the greater the thickness of the gloves and the number of layers the more the manual dexterity levels of performance are degraded. This is a common outcome in several of the studies reviewed by Dianat et al. (2012), for example Plummer et al. (1985) or Muralidhar et al. (1999). The cut-resistant gloves also reduced the ability to bend the hand, making it difficult to perform tasks requiring fine and gross finger dexterity and gross movement of the hand. The worst performing cut-resistant glove was C which was stiff and inflexible and made it difficult for subjects to pick up small items and to bend their hands. We also observed that the surface texture of gloves A and B were slightly ‘sticky’ which allowed the subjects to pick up and grip small objects more easily.

We found that the sizing of all the layers of gloves was critical to obtain the highest level of manual dexterity. If the gloves were not available in intermediate sizes the wearer had to choose a glove from full or half sizes which did not fit snugly, increasing the bulk and decreasing dexterity. It is critical when choosing gloves that the available sizes and proportions (e.g. finger length) match the whole of the user population, and takes account of size modification caused by layering. The importance of correct glove sizing has also been highlighted by Moore et al. (1995).

Although the glove ensemble is of great importance to manual dexterity, suit design also had an effect. The ring on AFS ND 1-piece made the wrist bulkier. The positioning of valves (particularly with AFS ND 2-piece, where subjects commonly had to hold the air supply valve on the front of the suit hood out of their line of sight when carrying out some activities—see Fig. 1) and the wearing of hoods also reduced the field of view and distorted the vision, and interfered with some of the manual dexterity tests. Therefore, it is also important to consider the clothing ensemble that will be worn with the gloves as it can impact the performance of the glove system.

In the assessment of the CL4 gloves, the subjects performed the tests better in a glove box with normal laboratory wear than when wearing an AFS, except in the case of the Minnesota turning test where the test was performed marginally better on a bench top in an AFS. The poor performance on this test in both the safety cabinet (AFS) and the glove box (no AFS) may have been because of the restricted space: the interaction of the AFS with the safety cabinet, and the fixed location of the integrated gloves on the glove box, both restricted reach. This demonstrates that it is not only the clothing ensemble that can be important but also interactions between clothing ensembles and other work equipment.

Our glove assessments have also shown that the BS EN 420 pin test (BSI, 2003b) does not provide much discrimination between performance levels unless there is a big difference between the gloves, even when smaller diameter pins have been added. The subjects tend to be able to pick up either all or none of the pins, giving poor discrimination between glove types. This means of assessment is therefore not a good test to determine the most usable gloves from a range of similar types—its primary function is to demonstrate a minimum level of performance for the purposes of product certification. Other dexterity assessment tests described here provided superior discrimination capability.

Hands and feet of AFS wearers were rated as hotter and the skin wetter than other parts of the body. This may be because there is little or no airflow through the boots and gloves and the skin is encapsulated in impermeable glove material so there is little sweat evaporation. This is important, as the skin on the hands in particular will absorb the accumulating sweat leading to maceration, i.e. swelling of the epidermal layer of the skin and reduced dexterity.

In order to select the best performing gloves for the workplace a series of assessments are required, which include both protection and functionality. Protection should always be balanced against loss of manual dexterity, especially in safety-critical or time-critical jobs. For example, in Tables A1, A2 and A4 is available as supplementary data at Annals of Occupational Hygiene online., and Table 3 it is clear that simple tasks carried out in gloved hands can take more than twice as long as when no gloves are used. Where safety is related to time of working, as in radioactively contaminated environments, the extension of exposure time caused by the use of necessary gloves must be taken into account. It is possible to adopt the use of manual dexterity tests to help in the selection of the best gloves for use in the workplace to minimize such effects. These tests should be selected to reflect the type of tasks that take place in the workplace and tests devised that mimic the work place tasks (e.g. gross hand movements or fine finger dexterity). This will apply to any glove application, and not just to ND or CL4 work.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data can be found at http://annhyg.oxfordjournals.org/.

FUNDING AND DISCLAIMER

This publication and the work it describes were funded by the HSE and ONR. Its contents, including any opinions and/or conclusions expressed, are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect HSE policy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions made by Rhiannon Mogridge and Duncan Webb in the planning and execution of this study, all the subjects who participated in the trials, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), Office of Nuclear Regulation (ONR), and industry stakeholders who supplied equipment for testing, and other HSL staff who assisted in the trials.

REFERENCES

- Bensel CK. (1993) The effects of various thicknesses of chemical protective gloves on manual dexterity. Ergonomics; 36: 687–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BSI. (2003a) BS EN 388:2003. Protective gloves against mechanical risks. London: British Standards Institution. [Google Scholar]

- BSI. (2003b) BS EN 420:2003+A1:2009. Protective gloves. General requirements and test methods. London: British Standards Institution. [Google Scholar]

- BSI. (2001) BS EN ISO 10551:2001. Ergonomics of the thermal environment. Assessment of the influence of the thermal environment using subjective judgment scales. London: British Standards Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Dianat I, Haslegrave CM, Stedmon AW. (2012) Methodology for evaluating gloves in relation to the effects on hand performance capabilities: a literature review. Ergonomics; 55: 1429–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabeck T, Boucek CD, Buffington CW. (2009) Wearing the wrong size latex surgical gloves impairs manual dexterity. J Occup Environ Hyg; 7: 152–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havenith G, Heus R. (2004) A test battery related to ergonomics of protective clothing. Appl Ergon; 35: 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafayette Instrument. (1998) Complete Minnesota Manual Dexterity Test (CMDT). Test Administrator’s Manual #32023A. Revised Edition. Available from http://www.lafayetteevaluation.com/ Accessed 22 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lafayette Instrument. (1999) Purdue Pegboard Model #32020. Instructions and Normative Data & Purdue Pegboard Quick Reference Guide #32020. Revised Edition. Available from http://www.lafayetteevaluation.com/ Accessed 22 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lafayette Instrument. (2002) Hand Tool Dexterity Test Model 32521. Owner’s/Operators’ Manual. Available from http://www.lafayetteevaluation.com/ Accessed 22 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mathiowetz V, Weber K, Kashman N, et al. (1985) Adult norms for the nine hole peg test of finger dexterity. Occup Ther J Res; 5: 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Moore BJ, Solipuram SR, Riley W. (1995) The effect of latex examination gloves on hand function. In Proceedings of the 39th annual meeting of the human fcators and ergonomics society, 9–13 October 1995, San Diego CA. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, pp. 582–585 [Google Scholar]

- Muralidhar A, Bishu RR, Hallbeck MS. (1999) The development of an ergonomic glove. Appl Ergon; 30: 555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara JM. (1989) The effect of pressure suit gloves on hand performance. I Proceedings of the 33rd annual meeting of the human factors society, 16–20 October 1989, Denver. Santa Monica, CA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer AM, Stobbe T, Ronk R, et al. (1985) Manual dexterity evaluation of gloves used in handling hazardous materials. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Meeting of the Human Factors Society. Baltimore, MD: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, pp. 819–823 [Google Scholar]

- Vanggaard L. (2007) Protection of hands and feet. In Goldman RF, Kampmann B, editors. Handbook on clothing: biomedical effects of military clothing and equipment systems. Second edition. NATO Research Study Group 7, Biomedical Aspects of Military Clothing, Panel VIII. Chapter 7a. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.