Abstract

At deep-sea vent systems, hydrothermal emissions rich in reductive chemicals replace solar energy as fuels to support microbial carbon assimilation. Until recently, all the microbial components at vent systems have been assumed to be fostered by the primary production of chemolithoautotrophs; however, both the laboratory and on-site studies demonstrated electrical current generation at vent systems and have suggested that a portion of microbial carbon assimilation is stimulated by the direct uptake of electrons from electrically conductive minerals. Here we show that chemolithoautotrophic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacterium, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, switches the electron source for carbon assimilation from diffusible Fe2+ ions to an electrode under the condition that electrical current is the only source of energy and electrons. Site-specific marking of a cytochrome aa3 complex (aa3 complex) and a cytochrome bc1 complex (bc1 complex) in viable cells demonstrated that the electrons taken directly from an electrode are used for O2 reduction via a down-hill pathway, which generates proton motive force that is used for pushing the electrons to NAD+ through a bc1 complex. Activation of carbon dioxide fixation by a direct electron uptake was also confirmed by the clear potential dependency of cell growth. These results reveal a previously unknown bioenergetic versatility of Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria to use solid electron sources and will help with understanding carbon assimilation of microbial components living in electronically conductive chimney habitats.

Keywords: extracellular electron transfer, hydrothermal vents, iron oxidizing bacteria, carbon assimilation, electrolithoautotrophy

Introduction

Chemolithoautotrophs are a class of organisms that conserve their energy, electrons, and carbon from inorganic chemical sources. As opposed to phototrophs that harvest energy from the sun, they are able to synthesize their own organic molecules from the fixation of carbon dioxide under the complete absence of solar radiation. The discovery of deep-sea hydrothermal vents has revealed the physiologically and phylogenetically diverse life around the vents (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999; Reysenbach and Shock, 2002; Takai et al., 2013), and the existence of chemolithoautotroph-dependent ecosystems has sparked interest in determining the unexplored bioenergetic underpinnings of their energy yielding and carbon assimilation metabolisms (Takai et al., 2006; Baaske et al., 2007; Martin et al., 2008; Meierhenrich et al., 2010; Nakamura et al., 2010; Sander and Koschinsky, 2011; Girguis and Holden, 2012; Sievert and Vetriani, 2012; Yamamoto et al., 2013).

In such deep-vent systems, the hydrothermal fluids abundant with reductive chemicals such as H2, H2S, and Fe2+ are formed through high-temperature seawater-rock interaction (Takai and Horikoshi, 1999; Reysenbach and Shock, 2002; Takai et al., 2013). Considering that chemolithoautotrophs are able to conserve energy by coupling oxidation of the reductive hydrothermal fluid and reduction of the oxidative sea water containing sulfate, nitrate, and oxygen, etc., it is generally believed that nearly all microbial populations and ecosystems around deep-sea hydrothermal vents are fostered by existing diffusible reductive chemicals as energy and electron sources (Baaske et al., 2007; Sander and Koschinsky, 2011). While the validity of this conceptual framework has been well established, important details regarding the bioenergetics of microbial energy yield from geothermal sources remain open to question (Nakamura et al., 2010; Girguis and Holden, 2012; Sievert and Vetriani, 2012; Yamamoto et al., 2013; Yamaguchi et al., 2014).

Noteworthy, a recent finding of geo-electrical current generation across a wall of black-smoker chimney pointed to “electrical current flow” as a new way of energy transport from hydrothermal fluid to seawater (Nakamura et al., 2010; Yamamoto et al., 2013). Since electrical current is triggered by different redox potential of spatially segregated two redox couples, energetics that underpins energy transport to microbial niches profoundly differs from the commonly accepted notion of mass transfer, that is, energy propagation is driven by diffusion and convection of soluble reductive molecules (Baaske et al., 2007; Sander and Koschinsky, 2011). Moreover, other important findings (Nealson and Saffarini, 1994; Myers and Myers, 1997; Newman and Kolter, 2000; Gorby et al., 2006; Fredrickson et al., 2008; Marsili et al., 2008; Nakamura et al., 2009, 2013; Coursolle et al., 2010; Lovley, 2012; Mogi et al., 2013; Okamoto et al., 2013, 2014; Bose et al., 2014) of microbial extracellular electron transfer to/from metallic and/or semiconductive minerals have encouraged us to propose “electrolithoautotrophs” as the third type of microbial energy yielding metabolisms which can utilize carbon dioxide to synthesize organic matters by using electrons directly taken from solid-inorganic electron donors. According to these findings, here we propose a hypothesis that not only the diffusible reductive compounds, but also the high-energy electrons directly transported from the inner hydrothermal fluid through mineral conduit, may serve as a primary energy source for microbial ecosystems in the deep ocean (Nakamura et al., 2010; Yamamoto et al., 2013).

To examine the validity of the hypothetical metabolic pathway for electrolithoautotrophic carbon assimilation, herein we cultivated the chemolithoautotrophic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacterium, Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, in Fe2+-ions free electrochemical reactors. Using site-specific chemical marking for intracellular electron-transfer chains involved in carbon assimilation, we demonstrate the previously unaccounted ability of an Fe(II)-oxidizing bacterium to switch the metabolic mode from chemosynthesis to hypothetical electrolithoautotrophic carbon assimilation under the conditions that electrical current is the only source of energy and electrons for their carbon assimilation.

Materials and Methods

Cell Preparation

Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (ATCC23270) was cultured in DSMZ medium 882 (132 mg L-1 (NH4)2SO4, 53 mg L-1 MgCl26H2O, 27 mg L-1 KH2PO4, 147 mg L-1 CaCl22H2O, and trace elements) supplemented with ferrous iron (66 mM) as an electron source and incubated aerobically at 30°C with shaking at 150 rpm in Erlenmeyer flask (volume of medium: 150 mL). The pH of solutions was adjusted to 1.8 using 5 M H2SO4. Subsequently, the culture was centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 10 min, and the pelleted cells were washed vigorously with a fresh medium at pH 1.8. This process was repeated more than three times to remove soluble Fe2+ ions and insoluble iron oxides from the cell culture prior to being used for electrochemical experiments.

Electrochemical Measurements

A single-chamber three-electrode system equipped with the working electrode on the bottom surface of the reactor was used for the electrochemical analysis of intact cells. A conducting glass substrate [fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO)-coated glass electrode, resistance: 20 Ω/square, size: 30 mm × 30 mm; SPD Laboratory, Inc.] was used as the working electrode. The reference and counter electrodes were Ag/AgCl (KCl sat.) and a platinum wire, respectively. An air-exposed DSMZ medium 882 was used as an electrolyte. The pH of solutions was adjusted to 1.8 using 5 M H2SO4. The head space of the reactor was purged with air which is the source of N2, O2, and CO2.

Chemical Marking Experiments

Coordination of CO to heme proteins in living cells was carried out by bubbling the cell suspension of A. ferrooxidans with CO gas for 10 min in the electrochemical reactor (Shibanuma et al., 2011). For the photocurrent measurements, a 1000-w Xe lamp (Ushio) equipped with a monochromator with a band width of 10 nm was used as an excitation source to irradiate light from the bottom of the electrochemical cell. For the inhibitor experiment of a bc1 complex, 1 v/v % Antimycin A solubilized in methanol was added in the electrochemical reactor. The final concentration of Antimycin A was 100 μM.

Results and Discussion

Branched Electron-Transfer Chain of A. ferrooxidans

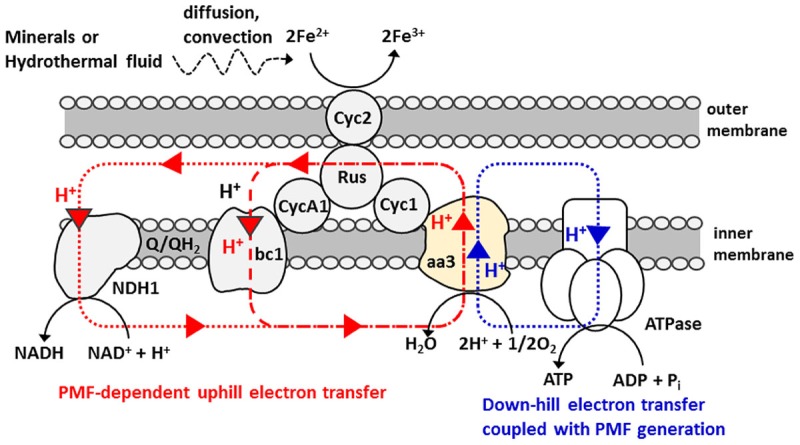

The electron transfer pathways spanning from the outer to inner-membrane of A. ferrooxidans has been extensively studied and the bifurcated chain composed of “down-hill (exergonic)” and “up-hill (endergonic)” pathways has been identified (Scheme 1) (Sugio et al., 1981; Ingledew, 1982; Elbehti et al., 1999, 2000; Yarzábal et al., 2002; Brasseur et al., 2004; Valdés et al., 2008; Quatrini et al., 2009; Bird et al., 2011; Shibanuma et al., 2011). Of particular note is that like Shewanella and Geobacter species known to have an ability for the direct extracellular electron transfer to and from an electrode, A. ferrooxidans also has c-type cytochromes (Cyc 2) on their outer-membrane compartments (Yarzábal et al., 2002). Electrons gained by Fe2+ oxidation at Cyc 2 are used for O2 reduction via a down-hill pathway, which in turn generates proton motive force (PMF) that is used for pushing the electron to a bc1 complex via an up-hill pathway and/or triggering ATP synthesis (Sugio et al., 1981; Ingledew, 1982; Elbehti et al., 1999, 2000; Yarzábal et al., 2002; Brasseur et al., 2004; Valdés et al., 2008; Quatrini et al., 2009; Bird et al., 2011; Shibanuma et al., 2011). In the following experiments, A. ferrooxidans was inoculated in an electrochemical reactor without Fe2+ ions and examined if the PMF-dependent up-hill pathway is activated by the direct electron uptake from an electrode, instead of the oxidation of diffusible Fe2+ ions.

SCHEME 1.

Bifurcated electron and proton transfer model of Fe(II) oxidation in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans (Sugio et al., 1981; Ingledew, 1982; Elbehti et al., 1999, 2000; Brasseur et al., 2004; Valdés et al., 2008; Quatrini et al., 2009; Bird et al., 2011). A small periplasmic blue copper protein (rusticyanin, Rus) has been proposed as a branch point to switch an electron flow between NAD+ and O2. Proton circuit for a down-hill and an up-hill electron-transfer reaction is indicated by blue and red dotted line, respectively. Electron and energy delivery to the cells for carbon fixation is based on the diffusion and/or convection of soluble Fe2+ ions.

Direct Uptake of Electrons from an Electrode into Cells

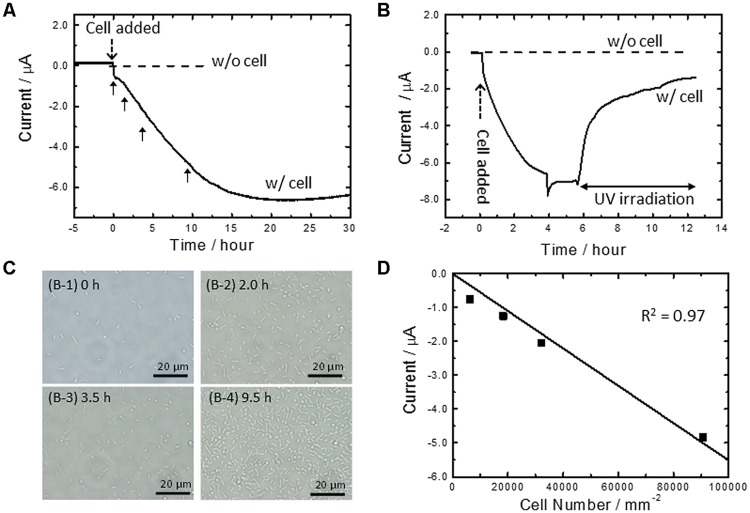

Figure 1A shows current vs. time curves for A. ferrooxidans cultivated in the absence of Fe2+ ions. In the present system, a conducting glass electrode (FTO) poised at +0.4 V (vs. SHE) acts as a sole source of electrons, and dissolved O2 and CO2 are an electron acceptor and a carbon source, respectively. In the absence of bacteria, we detected no electrical current generation (broken line, Figure 1A). On the other hand, in the reactors containing cells, the cathodic current gradually increased to approximately 7 μA after 20 h of cultivation (solid line, Figure 1A). The marked difference in current density depending on the presence of cells indicates that the cathodic current was derived from the metabolic activity of cells. Furthermore, in-situ sterilization of cells with the deep-UV (254 nm) irradiation immediately suppressed the cathodic current generation (Figure 1B). Almost no electrical response was observed after 6 h of sterilization, confirming the strong coupling of metabolic activity to electrical current generation.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Current vs. time measurements for microbial current generation by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans cells on an fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) electrode in the absence of Fe2+ ions (solid line) at +0.4 V (vs. SHE). Current vs. time measurements without cells at +0.4 V was also depicted as a reference (broken line) (B) Effects of the deep-UV (254 nm) irradiation to the microbial current generation by the cells in the absence of Fe2+ ions at +0.4 V (solid line). Current vs. time measurements without cells at +0.4 V was also depicted as a reference (broken line). (C) In-situ optical microscope observation of an FTO electrode surface at the indicated time (panel A) after cell inoculation. (D) Plot of microbial current against cell number attached on an electrode surface obtained from in-situ optical microscope observation (panels A and B). The squares of the correlation coefficients were estimated by the addition of the point of origin to the obtained data. The geometric area of the FTO electrode was 3.14 cm2. Initial OD500 was 0.02.

It is noted that the cathodic current generation by A. ferrooxidans in Figure 1A is mostly derived from the cells attached on an electrode, rather than planktonic cells. This was confirmed by in-situ counting of cell number on the FTO electrode with simultaneous monitoring of electrical current generation (Figures 1C,D). Since an FTO electrode is optically transparent and placed on the bottom surface of the electrochemical reactor, optical microscope images of the electrode surface can be acquired during electrical current generation by A. ferrooxidans. Figure 1C shows the in-situ optical microscope observation of the FTO electrode surface at the indicated time in Figure 1A after the cell was added in the electrochemical reactor. We plotted current against cell number to quantify the contribution of the electrode-attached cells for the cathodic current generation. As shown in Figure 1D, the microbial current exhibited a negative correlation with the cell number, as a fitted line passed through the point of origin with a high correlation coefficient (r2 = 0.97). This means that the current production was indeed dominated by the extracellular electron transfer of the cells directly attaching on the electrode surface. In other words, it appears that the gradual increase in the cathodic current in Figure 1A correlates with the establishing process of the electrical conduits to the electrode poised at +0.4 V with the cells settled down to the bottom part of the reactor.

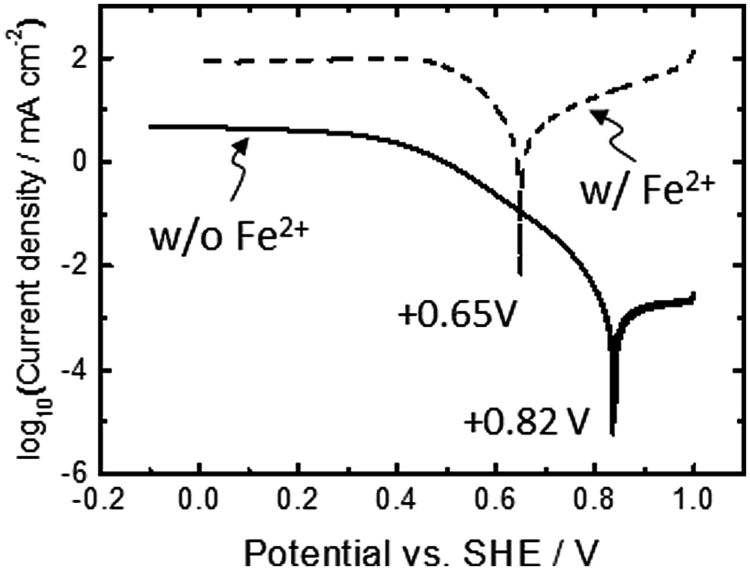

To evaluate the redox potential of electrical conduits established at the cell-electrode interface, electrodes covered with viable cells were examined by linear sweep (LS) voltammetry (solid line, Figure 2). As a reference, we also conducted LS voltammetry for cell cultures containing soluble Fe2+ ions, a system known as electrochemical cultivation of A. ferrooxidans (broken line, Figure 2) (Yunker and Radovich, 1986; Matsumoto et al., 1999, 2002; Ishii et al., 2012). In the presence of Fe2+ ions, the onset potential for cathodic current generation was estimated to be +0.65 V, as indicated in the peak in the logarithmic plot for current. This value is close to the redox potential of Fe3+/Fe2+ couple and consistent well with the previously reported model for electrochemical cultivation of A. ferrooxidans (Yunker and Radovich, 1986; Matsumoto et al., 1999, 2002; Ishii et al., 2012). Namely, diffusible Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions serve as an electron shuttle which bridges electron transfer between planktonic cells and electrodes. Meanwhile, the LS voltammogram for the electrode-attaching cells provided one peak at +0.82 V, and no peak assignable to diffusible Fe3+/Fe2+ redox couple was observed. This is the clear indication that the electrode-attaching cells established the different conduit of electrons to the FTO electrode rather than the Fe3+/Fe2+ redox couple, which serves as an important information for understanding the bioenergetics of PMF-dependent electrolithoautotrophic carbon assimilation (discuss later). Since the cathodic current generation was dominated by the cells directly attaching on an electrode surface (Figure 1D), the LS voltammetry results suggest the existence of outer-membrane-bound redox protein at a midpoint potential of +0.82 V, which bridges an electron donor of an FTO electrode to inner electron-trasnsfer chains responsible for carbon fixation.

FIGURE 2.

Linear sweep (LS) voltammograms for A. ferrooxidans cultivated in the presence (broken line) and absence (solid line) of Fe2+ ions (66 mM). A scan rate was 0.1 mV s-1. Initial OD500 was 0.02.

In-Vivo Monitoring Down-Hill Electron-Transfer Pathway

To identify the inner electron-trasnsfer chains responsible for the cathodic current generation and to examine if the PMF-dependent up-hill pathway is activated by direct uptake of electrons from an electrode, we applied the artificial photochemical reaction to A. ferrooxidans. As previously reported (Shibanuma et al., 2011), the treatment of viable cells with CO allows for monitoring the electron-transfer reaction mediated by heme proteins under in-vivo conditions, since the redox activities of hemes are blocked upon CO binding and subsequently reactivated by photodissociation of CO. This technique enables us to identify the specific heme proteins involved in current generation by examining the wavelength dependency of photocurrent response. In this experiment, A. ferrooxidans cells inoculated in an Fe2+-free electrochemical reactor were treated with CO and irradiated by the monochromic light with a band width of 10 nm in a course of microbial current generation.

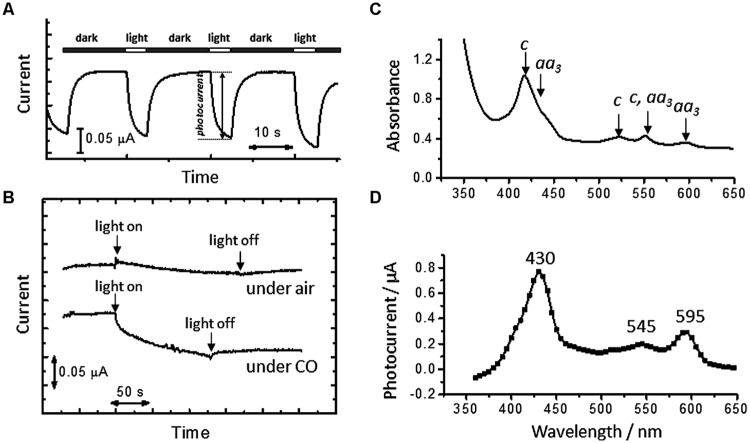

Figure 3A shows time courses of microbial current at an electrode potential of +0.4 V under CO atmospheres. Upon the treatment of the cells with CO, the microbial current decreased, suggesting that the formation of CO-ligated heme in living cells inhibited the extracellular electron-transfer reactions of A. ferrooxidans. The drop in the microbial current caused by CO was recovered upon visible-light irradiation; in contrast, visible-light irradiation induced little change in the current generation under N2 atmospheres (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Time courses of microbial current generation in the absence of Fe2+ ions under CO atmospheres. White and black bars indicate the period for light irradiation and dark conditions, respectively. An electrode potential was +0.4 V (vs. SHE). (B) Time courses of microbial current at an electrode potential of +0.4 V under air and CO atmospheres. (C) Diffuse transmission UV-vis spectrum of whole cells of A. ferrooxidans suspended in a DSMZ medium containing Na2S2O4 as a reductant under CO atmospheres. (D) An action spectrum of the microbial current recovered by visible-light irradiation under a CO atmosphere. Initial OD500 was 0.02.

A whole cell of A. ferrooxidans has multiple kinds of heme proteins, as indicated by UV-visible spectra of cell suspensions under CO atmospheres in the presence of Na2S2O4 (50 mM) as a reductant (Figure 3C). It is seen from the spectral region of Q bands that the cell has a-type (∼550 and ∼600 nm) and c-type (∼525 and ∼550 nm) cytochromes. To clarify the origin of the light-induced current recovery, excitation wavelength dependency was investigated. The action spectrum of CO-treated cells resolved the three bands peaked at 430, 545, and 595 nm, which are well-correlated with the Soret (429 nm) and Q (546 and 590 nm) bands of a CO-ligated aa3 complex, respectively (Figure 3D) (Horie et al., 1983). This indicates that the current recovery due to visible-light irradiation is predominantly derived from the photodissociation of the CO ligand of an aa3 complex. Namely, the photodissociation generates redox-active hemes and revives the cellular respiratory electron transport reactions. The suppression of microbial current observed immediately after stopping visible-light irradiation (Figure 3A) is due to the recombination of CO with an aa3 complex.

In-Vivo Monitoring of up-Hill Electron Transfer Pathway

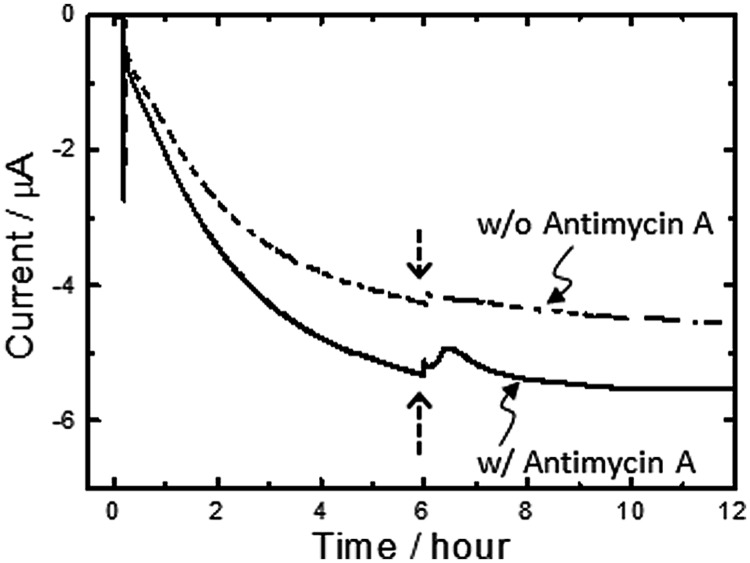

It is worth noting here that the aa3 complex of A. ferrooxidans is expressed under Fe2+-grown conditions and positioned at a terminal of the down-hill pathway (Scheme 1) (Sugio et al., 1981; Ingledew, 1982; Elbehti et al., 1999, 2000; Yarzábal et al., 2002; Brasseur et al., 2004; Valdés et al., 2008; Quatrini et al., 2009; Bird et al., 2011). Given that an aa3 complex is responsible for the generation of PMF for up-hill pumping of electrons and/or initiating ATP synthesis, it can be deduced that a portion of electrons directly taken from an electrode are pushed up-hill to NAD+ through a bc1 complex. To assure the occurrence of PMF-dependent reverse electron transfer, we added a bc1 complex inhibitor, Antimycin A (Elbehti et al., 2000), to the electrode-attaching cells in the course of microbial current generation. As expected, upon addition of 1v/v % Antimycin A solubilized in methanol (final concentration of Antimycin A is 100 μM), the transient, but clear suppression of the microbial current generation by approx. 6% was observed (solid line, Figure 4). In contrast, the addition of 1 v/v % methanol lacking Antimycin A caused subtle change in the microbial current (broken line, Figure 4), confirming that the current suppression was due to the inhibition of the bc1 complex.

FIGURE 4.

Effects adding a bc1 complex inhibitor, Antimycin A, on microbial current generation for A. ferrooxidans cultivated in the absence of Fe2+ ions at an electrode potential of +0.4 V (vs. SHE). Antimycin A solubilized in methanol (final concentration of Antimycin A is 100 μM) was added into electrochemical reactors at the time points indicated with an arrow (solid line). Methanol lacking Antimycin A was also added into electrochemical reactors as a control experiment (broken line). Initial OD500 was 0.02.

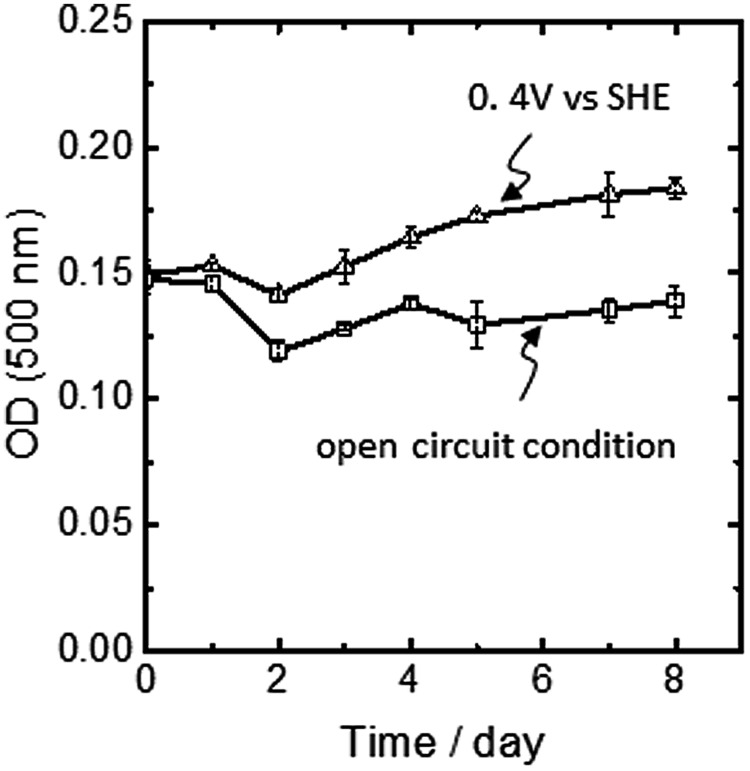

In A. ferrooxidans, the PMF-dependent up-hill electron transfer is a physiologically important phenomenon, since carbon dioxide fixation via the Calvin cycle is coupled to this process. Figure 5 shows the time course of optical cell density at 500 nm (OD500) obtained for A. ferrooxidans cells inoculated in an Fe2+-ion-free electrochemical reactor for 8 days. Under the condition that the electrode potential was poised at +0.4 V, OD500 increased with incubation time. In contrast, when the cell was incubated under the same condition with the exception that no external potential was applied to the FTO electrode (open circuit condition), no growth of the cells was observed. Here, we should emphasize that under the open circuit condition, the electron flow from the FTO electrode to the cells was fully ceased and thus the electrode no longer functioned as an electron source for microbial growth. Therefore, the clear potential dependency of the cell growth indicates that the cathodic current was being used not only for PMF generation, but also for carbon dioxide fixation and cellular maintenance via an endergonic electron-transfer reaction.

FIGURE 5.

Changes in the optical cell density at 500 nm of A. ferrooxidans inoculated in an Fe2+-ion free electrochemical rector under the potential static condition at +0.4 V vs. SHE (open triangle) and the open circuit condition (open square). Error bars indicate the standard error of the means calculated with data obtained from three individual experiments for the potential static condition and two individual experiments for the open circuit condition, respectively.

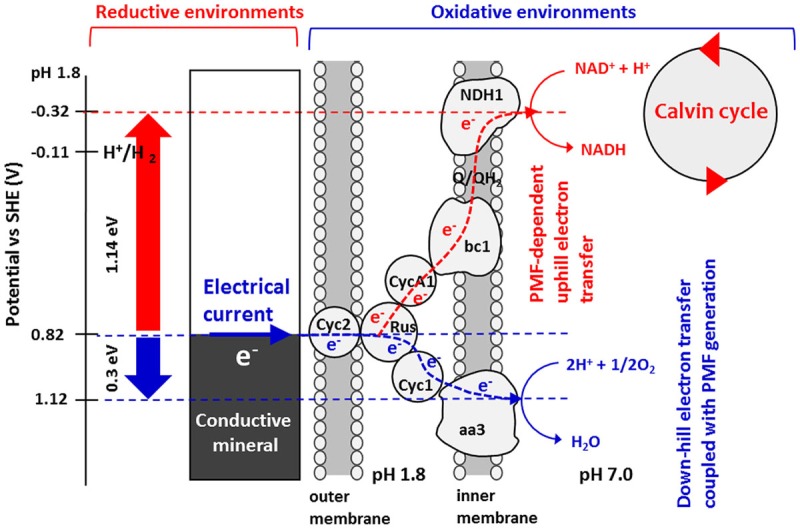

Taken together, the results obtained by in-vivo electrochemistry with site-specific chemical marking suggest the bioenergetic pathway illustrated in Scheme 2 as a model for PMF-dependent electrolithoautotrophic carbon assimilation of A. ferrooxidans. As estimated from LS voltammetry (Figure 2), A. ferrooxidans cells establish the direct electrical conduit to a solid electron donor at the potential of +0.82 V, which is 0.17 V more positive than the diffusible redox couple of Fe3+/Fe2+ for chemolithoautotrophic carbon assimilation. Although Cyc 2 is located at the outer-cell surface of A. ferooxidance, we cannot exclude the possibility that self-secreted redox molecules are involved in the direct extracellular electron transfer, as recent studies demonstrated that self-secreted flavin acts as a bound-cofactor of outer-membrane c-type cytochromes of Shewanella oneidensis (Okamoto et al., 2013) and Geobacter sulfurreducens (Okamoto et al., 2014) for initiating the direct electron transfer from cells to electrodes. The involvement of H2 as an electron carrier for the direct extracellular electron transfer and cell growth of A. ferooxidance can be excluded, since the onset potential of direct extracellular electron transfer is approximately 900 mV more positive than the redox potential of hydrogen evolution [E(H+/H2) = - 0.11 V vs. SHE at pH1.8]. Even in the presence of extracellular enzymes suggested by Methanococcus maripaludis (Deutzmann et al., 2015), H2 production by proton reduction is thermodynamically unfeasible in our experimental conditions.

SCHEME 2.

Energy diagram for PMF-dependent electrolithoautotrophic carbon fixation in A. ferrooxidans. A. ferrooxidans cell extracts electrons directly from solid electron sources such as conductive minerals and electrodes at a potential of +0.82 V vs. SHE. Electrons are used for O2 reduction via a down-hill pathway, which in turn generates PMF that is used to elevate the energy of electrons to reduce NAD+ to NADH, therefore triggering Calvin cycle. From the energy difference between the input electron and the midpoint potential of NAD+/NADH redox at cytoplasmic pH, it is estimated that A. ferrooxidans elevates the energy of electrons using PMF by 1.14 eV.

For initiating the carbon fixation by Rubisco enzymes, A. ferrooxydans cells require sufficient reductive energy to convert NAD+ to NADH in the cytoplasm through a bc1 complex. As the reversible potential of the NAD+/NADH redox couple is -0.32 V at cytoplasmic pH, we can estimate that A. ferrooxydans cells are capable of elevating the energy of electrons by 1.14 V using PMF through exergonic electron flow to O2 (Scheme 2). Although how the electron flow switches between NAD+ and O2 is not known, a small periplasmic blue copper protein (rusticyanin, Rus) has been proposed as a branch point (Valdés et al., 2008; Quatrini et al., 2009). From the inhibition rate of cathodic current generation by Antimycin A (Figure 4), we can estimate that electrons gained from an FTO electrode split to an up-hill and a down-hill pathway with a ratio of approximately 1 to 15 under the condition of the present experiments. The presence of two functional bc1 complexes are known in A. ferrooxidans. One (PetA1B1C1) functions only in up-hill direction in iron-grown cells (Elbehti et al., 2000), whereas the other (PetA2B2C2) has been shown to function only in down-hill mode in sulfur-grown cells (Brasseur et al., 2004). Considering that the PMF-dependent up-hill pathway is activated for the cells attached on the electrode surface, it is assumable that the former one is responsible in the observed electrolithoautotrophic carbon assimilation.

Summary

In the present study, we demonstrated for the first time that the chemolithoautotrophic Fe(II)-oxidizing bacterium, A. ferrooxidans, is capable of using electrical current as the energy source for carbon assimilation. The finding of the metabolism switched from chemolithoautotrophy to electrolithoautotrophy demonstrates a previously unknown bioenergetic versatility of energy yielding metabolisms in Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria, which in turn supports our hypothesis (Nakamura et al., 2010; Yamamoto et al., 2013) highlighting the possibility of electrons to be a primary energy source for deep-sea hydrothermal ecosystems. Although recent studies have postulated that several microorganisms are capable of conducting a direct uptake of electrons from solid electron donors at highly negative redox potential ranging from -400 to -800 mV (vs. SHE; reviewed in Rabaey and Rozendal, 2010; Lovley and Nevin, 2013; Deng et al., 2015; Tremblay and Zhang, 2015), these potentials are too negative to be generated by natural environments, even at the highly reducing environments such as deep-sea alkaline hydrothermal vents (Martin et al., 2008). Accordingly, further investigation on PMF-dependent electrolithoautotrophy at geochemically relevant potential regions presented in this work will help understanding carbon assimilation of microbial components living around electronically conductive chimney walls. On-site electrochemical experiments at deep-sea hydrothermal vents are currently underway using a remotely operated vehicle equipped with the potentiostat and potential programmer system (Yamamoto et al., 2013), which will bring our understanding of electricity-dependent microbial habitats to a new realm.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. K. Takai, M. Yamamoto, and H. Makita of the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) for discussions about microbiological and biogeochemical aspects of deep-sea hydrothermal ecosystems, and Ms. T. Minami of RIKEN for the careful reading of the manuscript. This work was financially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 24000010, and by a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, Technology (MEXT), Japan (24655167) and The Canon Foundation.

References

- Baaske P., Weinert F. M., Duhr S., Lemke K. H., Russell M. J., Braun D. (2007). Extreme accumulation of nucleotides in simulated hydrothermal pore systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 9346–9351. 10.1073/pnas.0609592104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird L. J., Bonnefoy V., Newman D. K. (2011). Bioenergetic challenges of microbial iron metabolisms. Trends Microbiol. 19 330–340. 10.1016/j.tim.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose A., Gardel E. J., Vidoudez C., Parra E. A., Girguis P. R. (2014). Electron uptake by iron-oxidizing phototrophic bacteria. Nat. Commun. 5 3391 10.1038/ncomms4391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasseur G., Levicán G., Bonnefoy V., Holmes D., Jedlicki E., Lemesle-Meunier D. (2004). Apparent redundancy of electron transfer pathways via bc 1 complexes and terminal oxidases in the extremophilic chemolithoautotrophic Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1656 114–126. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursolle D., Baron D. B., Bond D. R., Gralnick J. A. (2010). The Mtr respiratory pathway is essential for reducing flavins and electrodes in Shewanella oneidensis. J. Bacteriol. 192 467–474. 10.1128/JB.00925-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X., Nakamura R., Hashimoto K., Okamoto A. (2015). Electron extraction from an extracellular electrode by Desulfovibrio ferrophilus strain IS5 without using hydrogen as an electron carrier. Electrochemistry 83 529–531. 10.5796/electrochemistry.83.529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deutzmann J. S., Sahin M., Spormann A. M. (2015). Extracellular enzymes facilitate electron uptake in biocorrosion and bioelectrosynthesis. MBio 6 e00496–e00515. 10.1128/mBio.00496-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbehti A., Brasseur G., Lemesle-Meunier D. (2000). First evidence for existence of an uphill electron transfer through the bc1 and NADH-Q oxidoreductase complexes of the acidophilic obligate chemolithotrophic ferrous ion-oxidizing bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Bacteriol. 182 3602–3606. 10.1128/JB.182.12.3602-3606.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbehti A., Nitschke W., Tron P., Michel C., Lemesle-Meunier D. (1999). Redox components of cytochrome bc-type enzymes in acidophilic prokaryotes I. Characterization of the cytochrome bc 1-type complex of the acidophilic ferrous ion-oxidizing bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Biol. Chem. 274 16760–16765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson J. K., Romine M. F., Beliaev A. S., Auchtung J. M., Driscoll M. E., Gardner T. S., et al. (2008). Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6 592–603. 10.1038/nrmicro1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girguis P. R., Holden J. F. (2012). On the potential for bioenergy and biofuels from hydrothermal vent microbes. Oceanography 25 213–217. 10.5670/oceanog.2012.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorby Y. A., Yanina S., Mclean J. S., Rosso K. M., Moyles D., Dohnalkova A., et al. (2006). Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 11358–11363. 10.1073/pnas.0604517103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie S., Watanabe T., Kumiko A. (1983). Studies on the ferricytochrome a-ferrocytochrome a3-carbon monoxide complex of mammalian cytochrome oxidase. Conditions for preparation and some properties. J. Biochem. 93 997–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingledew W. J. (1982). Thiobacillus ferrooxidans the bioenergetics of an acidophilic chemolithotroph. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 683 89–117. 10.1016/0304-4173(82)90007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T., Nakagawa H., Hashimoto K., Nakamura R. (2012). Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans as a bioelectrocatalyst for conversion of atmospheric CO2 into extracellular pyruvic acid. Electrochemistry 80 327–329. 10.5796/electrochemistry.80.327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R. (2012). Electromicrobiology. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66 391–409. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovley D. R., Nevin K. P. (2013). Electrobiocommodities: powering microbial production of fuels and commodity chemicals from carbon dioxide with electricity. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24 385–390. 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsili E., Baron D. B., Shikhare I. D., Coursolle D., Gralnick J. A., Bond D. R. (2008). Shewanella secretes flavins that mediate extracellular electron transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 3968–3973. 10.1073/pnas.0710525105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W., Baross J., Kelley D., Russell M. J. (2008). Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6 805–814. 10.1038/nrmicro1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto N., Nakasono S., Ohmura N., Saiki H. (1999). Extension of logarithmic growth of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans by potential controlled electrochemical reduction of Fe (III). Biotechnol. Bioeng. 64 716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto N., Yoshinaga H., Ohmura N., Ando A., Saiki H. (2002). Numerical simulation for electrochemical cultivation of iron oxidizing bacteria. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 78 17–23. 10.1002/bit.10173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meierhenrich U. J., Filippi J. J., Meinert C., Vierling P., Dworkin J. P. (2010). On the origin of primitive cells: from nutrient intake to elongation of encapsulated nucleotides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49 3738–3750. 10.1002/anie.200905465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogi T., Ishii T., Hashimoto K., Nakamura R. (2013). Low-voltage electrochemical CO2 reduction by bacterial voltage-multiplier circuits. Chem. Commun. 49 3967–3969. 10.1039/c2cc37986d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C. R., Myers J. M. (1997). Outer membrane cytochromes of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1: spectral analysis, and purification of the 83-kDa c-type cytochrome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1326 307–318. 10.1016/S0005-2736(97)00034-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura R., Kai F., Okamoto A., Hashimoto K. (2013). Mechanisms of long-distance extracellular electron transfer of metal-reducing bacteria mediated by nanocolloidal semiconductive iron oxides. J. Mater. Chem. A 1 5148–5157. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b01033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura R., Kai F., Okamoto A., Newton G. J., Hashimoto K. (2009). Self-constructed electrically conductive bacterial networks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48 508–511. 10.1002/anie.200804750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura R., Takashima T., Kato S., Takai K., Yamamoto M., Hashimoto K. (2010). Electrical current generation across a black smoker chimney. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 49 7692–7694. 10.1002/anie.201003311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nealson K. H., Saffarini D. (1994). Iron and manganese in anaerobic respiration: environmental significance, physiology, and regulation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 48 311–343. 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.001523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman D. K., Kolter R. (2000). A role for excreted quinones in extracellular electron transfer. Nature 405 94–97. 10.1038/35013189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto A., Hashimoto K., Nealson K. H., Nakamura R. (2013). Rate enhancement of bacterial extracellular electron transport involves bound flavin semiquinones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 7856–7861. 10.1073/pnas.1220823110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto A., Saito K., Inoue K., Nealson K. H., Hashimoto K., Nakamura R. (2014). Uptake of self-secreted flavins as bound cofactors for extracellular electron transfer in Geobacter species. Energy Environ. Sci. 7 1357–1361. 10.1039/c3ee43674h [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quatrini R., Appia-Ayme C., Denis Y., Jedlicki E., Holmes D. S., Bonnefoy V. (2009). Extending the models for iron and sulfur oxidation in the extreme acidophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. BMC Genomics 10:394 10.1186/1471-2164-10-394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabaey K., Rozendal R. A. (2010). Microbial electrosynthesis – revisiting the electrical route for microbial production. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 706–716. 10.1038/nrmicro2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reysenbach A. L., Shock E. (2002). Merging genomes with geochemistry in hydrothermal ecosystems. Science 296 1077–1082. 10.1126/science.1072483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander S. G., Koschinsky A. (2011). Metal flux from hydrothermal vents increased by organic complexation. Nat. Geosci. 4 145–150. 10.1038/ngeo1088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shibanuma T., Nakamura R., Hirakawa Y., Hashimoto K., Ishii K. (2011). Observation of in vivo cytochrome-based electron-transport dynamics using time-resolved evanescent wave electroabsorption spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50 9137–9140. 10.1002/anie.201101810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievert S., Vetriani C. (2012). Chemoautotrophy at deep-sea vents: past, present, and future. Oceanography 25 218–233. 10.5670/oceanog.2012.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugio T., Tano T., Imai K. (1981). Isolation and some properties of silver ion-resistant iron-oxidizing bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Agric. Biol. Chem. 45 2037–2051. 10.1271/bbb1961.45.1791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takai K., Horikoshi K. (1999). Genetic diversity of archaea in deep-sea hydrothermal vent environments. Genetics 152 1285–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai K., Nakagawa S., Reysenbach A.-L., Hoek J. (2013). “Microbial ecology of Mid-ocean ridges and back-arc basins,” in Back-Arc Spreading Systems: Geological, Biological, Chemical, and Physical Interactions eds Christie D. M., Fisher C. R., Lee S.-M., Givens S. (Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union; ) 185–213. [Google Scholar]

- Takai K., Nakamura K., Suzuki K., Inagaki F., Nealson K. H., Kumagai H. (2006). Ultramafics-Hydrothermalism-Hydrogenesis-HyperSLiME (UltraH3) linkage: a key insight into early microbial ecosystem in the Archean deep-sea hydrothermal systems. Paleontol. Res. 10 269–282. 10.2517/prpsj.10.269 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay P. L., Zhang T. (2015). Electrifying microbes for the production of chemicals. Front. Microbiol. 6:201 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdés J., Pedroso I., Quatrini R., Dodson R. J., Tettelin H., Blake R., et al. (2008). Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans metabolism: from genome sequence to industrial applications. BMC Genomics 9:597 10.1186/1471-2164-9-597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi A., Yamamoto M., Takai K., Ishii T., Hashimoto K., Nakamura R. (2014). Electrochemical CO2 reduction by Ni-containing iron sulfides: how is CO2 electrochemically reduced at bisulfide-bearing deep-sea hydrothermal precipitates? Electrochim. Acta 141 311–318. 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.07.078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M., Nakamura R., Oguri K., Kawagucci S., Suzuki K., Hashimoto K., et al. (2013). Generation of electricity and illumination by an environmental fuel cell in deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 52 10758–10761. 10.1002/anie.201302704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarzábal A., Brasseur G., Ratouchniak J., Lund K., Lemesle-Meunier D., Demoss J. A., et al. (2002). The high-molecular-weight cytochrome c Cyc2 of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans is an outer membrane protein. J. Bacteriol. 184 313–317. 10.1128/JB.184.1.313-317.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunker S., Radovich J. (1986). Enhancement of growth and ferrous iron oxidation rates of T. ferrooxidans by electrochemical reduction of ferric iron. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 28 1867–1875. 10.1002/bit.260281214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]