Abstract

Background

Osteoarthritis is a common chronic condition that affects many older Canadians and is a considerable cause of disability. Our objective was to describe the epidemiology of osteoarthritis in patients aged 30 years and older using electronic medical records (EMRs) in a Canadian primary care population.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we analyzed the EMRs of 207 610 patients over 30 years of age (extracted on December 31, 2012) who had at least one clinic visit during the preceding 2 years. We calculated the age–sex standardized prevalence of diagnosed osteoarthritis and its association with comorbidities and covariates available in the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network database.

Results

The estimated prevalence of diagnosed osteoarthritis was 14.2% (15.6% among women, 12.4% among men). The diagnosis of osteoarthritis was associated with several comorbidities: hypertension (prevalence ratio [PR] 1.17, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.15–1.18), depression (PR 1.26, 95% CI 1.22–1.3), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (PR 1.16, 95% CI 1.11–1.21) and epilepsy (PR 1.27, 95% CI 1.13–1.43). In addition, 56.6% of patients had received a prescription for a range of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, 45% of which were topical. Opioid medications were prescribed to 33% of patients for pain management.

Conclusion

Osteoarthritis is a common disease in middle-aged and older Canadians. It is more common in women than in men and is associated with comorbid conditions. Most patients with osteoarthritis received pharmacotherapy for inflammation and pain management. As the Canadian population ages, osteoarthritis will become an increasing burden for individuals and the health care system.

Osteoarthritis is a common chronic condition affecting many older Canadians and is a considerable cause of disability.1 It is the most common form of arthritis and is frequently diagnosed and managed in primary care.2 As the Canadian population ages, the burden of this condition on our health care system will increase, and we must look at trends in risk factors, diagnosis and management.

International reports on the prevalence of osteoarthritis diagnoses show an increasing number of patients with the condition.3 This is predominantly due to an increase in the number of people older than 60 years, as well as to an increase in obesity, a leading risk factor for osteoarthritis.4–7 Previous studies have provided information about the state of osteoarthritis in Canada.7–11 In British Columbia, an overall prevalence of 10.8% was found using administrative data (i.e., physician billing and hospital admissions data); by age 70–74 years, 30% of men and 40% of women had osteoarthritis. In Ontario, linked survey and administrative data showed that quality of life was 10%–25% lower among people with osteoarthritis than in the general population, and healthcare costs were 2–3 times higher than in the non-osteoarthritis group.10 Therefore there is a high prevalence, reduction of quality of life and a large economic burden associated with osteoarthritis in Canada.

These studies of arthritis in Canada come from surveys, administrative data and reporting systems.8–11 However, their results are often inconsistent and difficult to compare owing to variations in design and methods.12,13 Determining the prevalence of osteoarthritis can be difficult because estimates are sensitive to the case definition of osteoarthritis, the period used to estimate the period prevalence and the denominator population — specifically, the exclusion of very young ages. In 2012, a Canadian group (the CANRAD network) collaborating with international experts developed a consensus statement for using administrative data to study rheumatic disease to improve its consistency and value for arthritis research.14 Although this provides some continuity and comparability of findings from administrative data, primary care electronic medical records (EMR) can be a complementary source of information for occurrence estimates, workload, case profile (including comorbidities) and patterns of osteoarthritis in primary care over time. Direct clinical information on patient comorbidities, medications, weight, blood pressure and other risk factors, as well as the longitudinal nature of these data, are all important information that primary care EMRs can contribute.

For this study, we used a new source of health data from the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN), which is Canada’s first multidisease EMR-based surveillance system that collects longitudinal data on more than 500 000 patients from 600 primary care practices across Canada. We have developed validated case definitions for 8 chronic conditions, including the diagnosis of osteoarthritis, which takes into account prescribed medications, billing codes, laboratory tests and multiple diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (clinical modification) (ICD-9) to find cases.15,16 CPCSSN is a primary care network comprising 11 practice-based research networks in 7 Canadian provinces and 1 territory. The network extracts patient data from 12 different EMR vendor products. The details of the data extraction procedures have been previously described,17,18 and previous work has shown that the population of patients within the network is broadly representative of the primary care population in Canada.19

Our objectives were to estimate the prevalence of the diagnosis of osteoarthritis recorded in EMRs among men and women, to assess the association of the diagnosis of osteoarthritis with comorbidities and potential risk factors and to describe the pattern of medication prescription for people with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis in primary care.

Methods

Data sources and study population

We performed a retrospective cohort study to evaluate EMR data from more than 600 000 patients from 340 primary care providers participating in CPCSSN. The network received ethics approval from the research ethics boards of each host university for all networks and from the Health Canada Research Ethics Board.

We included all patients 30 years of age and older by December 31, 2012, who had at least one encounter with their provider’s practice in the preceding 24 months and who did not opt out of participation in CPCSSN. We excluded patients younger than 30 years, because osteoarthritis is an age-related condition with very low rates in this population. We used a 24-month contact period because most patients with a chronic condition will visit their primary care provider at least once in 2 years.20 We included patients identified as having osteoarthritis, based on CPCSSN case criteria, at any point in their available EMR record in our analysis and compared their data with those from patients without a diagnosis of osteoarthritis.14,15

A diagnosis of osteoarthritis in CPCSSN includes osteoarthritis and allied disorders, as well as spondylosis and allied disorders such as ankylosing vertebral hyperostosis. The diagnosis excludes intervertebral disc disorders, ankylosing spondylitis and other inflammatory spondylopathies and spinal stenosis. The algorithm identifies a case of osteoarthritis as any occurrence of ICD-9 codes 715 (osteoarthritis generalized involving unspecified site) or 721 (spondylosis) in the billing table or the problem list/encounter table. In a validation study of CPCSSN, this case definition had a sensitivity of 77.8% (95% confidence interval [CI] 74.5%–81.1%), a positive predictive value of 87.7% (95% CI 84.9%–90.5%) and a negative predictive value of 90.2% (95% CI 88.7%–91.8%) when compared with the reference standard of independent chart abstraction.15,16

Statistical analysis

We calculated the prevalence estimate of the diagnosis of osteoarthritis in the 2-year contact group by age and sex. In addition, we made direct age–sex-standardized prevalence estimates according to the Canadian national age–sex distribution based on data from the 2011 census. We then calculated prevalence ratios of 3 risk factors: patient’s rurality (determined by the middle digit of the first 3 digits of the patient’s postal code; if the digit is a “0,” it is considered by Canada Post to be a rural delivery route), BMI (underweight, BMI < 18; normal, 18 ≤ BMI < 25; overweight, 25 ≤ BMI < 30; obese, BMI ≥ 30) and smoking (never smoked, past smoker, current smoker). We performed 3 separate log-binomial regression analyses to calculate prevalence ratios, each controlling for age and sex of the study population.21 In addition to prevalence ratios, we report the corresponding 95% CIs and p values.

We analyzed the presence of comorbid conditions, adjusting for age and sex, using the same log-binomial approach and expressed the results in terms of prevalence ratios, 95% CIs and p values. In addition, we looked at the cumulative proportion of patients with a diagnosis of one or more of the other chronic diseases reported in CPCSSN among those with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis.

We assessed medication data by analyzing the pattern of medication use by patients with the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. We defined medication use as at least one prescription for that medication for the patient at any time in their EMR.

We used descriptive statistics and performed multivariate modeling using SAS version 9.3.

Results

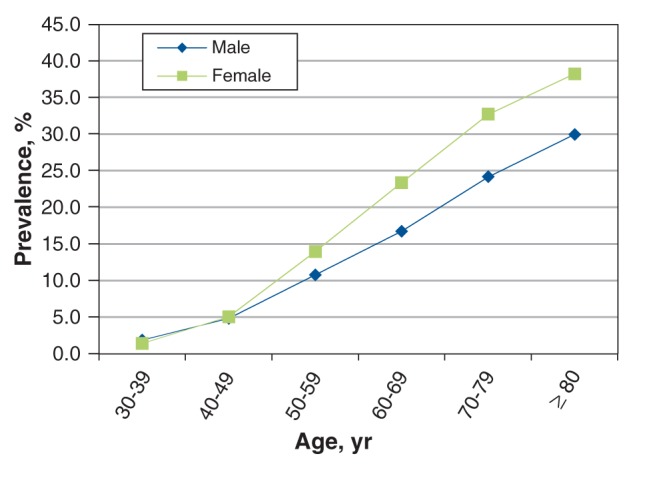

We found 207 610 patients aged 30 years and older who had at least 1 clinic visit in the 2 year period preceding December 31, 2012. Our case definition identified 29 562 patients with a diagnosis of osteoarthritis at any time in their records (Table 1). We found a marked increase in osteoarthritis prevalence with age, with estimates in women higher than those in men in each age group. The overall prevalence of osteoarthritis was 14.2% (95% CI 14.1–14.4), increasing from 1.6% (95% CI 1.5–1.8) in patients aged 30–39 years to 35.1% (95% CI 34.4–35.8) in those aged 80 years and older (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of the study population.

| Characteristic | No. (%)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with osteoarthritis n = 29 562† |

Patients without osteoarthritis n = 207 610† |

|||

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 67.4 | (13.4) | 53.5 | (15.7) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 10 807 | (36.6) | 76 265 | (42.8) |

| Female | 18 755 | (63.4) | 101 783 | (57.2) |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 22 094 | (76.0) | 133 508 | (77.3) |

| Rural | 6 979 | (24.0) | 39 137 | (22.7) |

| No. of comorbid conditions† | ||||

| 0 | 9 549 | (32.3) | 101 470 | (57.0) |

| 1 | 11 658 | (39.4) | 54 393 | (30.6) |

| 2 | 6 086 | (20.6) | 17 802 | (10.0) |

| 3 | 1 840 | (6.2) | 3 766 | (2.1) |

| ≥ 4 | 429 | (1.5) | 617 | (0.3) |

Note: SD = standard deviation. *Unless stated otherwise. †Limited to other conditions for which the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network has validated algorithms (i.e., hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, depression, epilepsy, Parkinson disease and dementia).

Table 2: Prevalence of osteoarthritis by patient age and sex.

| Age group, yr | No. (%)* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Overall | ||||

| 30–39 | 14 516 | (1.9) | 23 839 | (1.5) | 38 355 | (1.6) |

| 40–49 | 17 508 | (4.9) | 24 836 | (5.1) | 42 344 | (5.0) |

| 50–59 | 20 562 | (10.8) | 26 812 | (14.0) | 47 374 | (12.6) |

| 60–69 | 17 208 | (16.7) | 20 798 | (23.4) | 38 006 | (20.4) |

| 70–79 | 10 446 | (24.2) | 13 316 | (32.7) | 23 762 | (29.0) |

| 80+ | 6 832 | (30.0) | 10 937 | (38.2) | 17 769 | (35.1) |

| Overall | 87 072 | (12.4) | 12 0538 | (15.6) | 207 610 | (14.2) |

*Direct age–sex-standardized prevalence estimates according to the Canadian national age–sex distribution based on data from the 2011 census.

Figure 1:

Prevalence of osteoarthritis diagnoses in electronic medical records by patient age and sex.

In our regression model, the risk of osteoarthritis was comparable for patients in urban and in rural locations (Table 3). However, we found a significant increase in the risk of the diagnosis of osteoarthritis for patients who were underweight or obese compared with those within the normal BMI range. Although only 41.3% of the study population had any smoking data in their medical records, we saw a small but significant decrease in the risk of the diagnosis of osteoarthritis for current smokers compared with patients who had never smoked.

Table 3: Prevalence ratios for osteoarthritis adjusted for age and sex, by location of residence, BMI and smoking status.

| Characteristic* | PR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Location (n = 201 718) | ||

| Urban = ref | 1.00 | — |

| Rural | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 0.3 |

| BMI group (n = 136 765) | ||

| Underweight (< 18) | 1.11 (1.04–1.17) | < 0.001 |

| Normal (18–24) = ref | 1.00 | — |

| Overweight (25–29)† | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.004 |

| Obese (> = 30)‡ | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | < 0.001 |

| Smoking n = 85 705 | ||

| Never = ref | 1.00 | — |

| Past | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 0.2 |

| Current | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | < 0.001 |

Note: BMI = body mass index, CI = confidence interval, PR = prevalence ratio. *Location data missing for 5 892 (2.8%) patients; BMI data missing for 7 388 (25%) patients with osteoarthritis and 64 910 (36.5%) patients without osteoarthritis; smoking data missing for 15 980 (54%) patients with osteoarthritis and 105 925 (59.5%) patients without osteoarthritis. †p < 0.01. ‡p < 0.001.

We found that patients with the diagnosis of osteoarthritis had no increased risk of diabetes, dementia or Parkinsonism, but did have an increased risk of hypertension, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and epilepsy (Table 4). Our evaluation of multimorbidity showed that 67.7% of those with osteoarthritis, versus 43% of those without osteoarthritis, have at least one of the other CPCSSN-defined chronic conditions (Table 5).

Table 4: Age- and sex-adjusted prevalence ratios for comorbidity among patients with osteoarthritis.

| Comorbidity | PR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 1.17 (1.15–1.19) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | NS |

| Depression | 1.26 (1.22–1.30) | < 0.001 |

| COPD | 1.16 (1.11–1.21) | < 0.001 |

| Dementia | 1.00 (0.95–1.06) | NS |

| Epilepsy | 1.27 (1.13–1.43) | < 0.001 |

| Parkinsonism | 1.08 (0.93–1.24) | NS |

Note: CI = confidence interval, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, NS = not significant, PR = prevalence ratio.

Table 5: Prevalence of osteoarthritis by number of other conditions (i.e., multimorbidity).

| No. of other conditions | Osteoarthritis present, % n = 29 562 |

Osteoarthritis absent, % n = 178 048 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 32.3 | 57.0 |

| 1 | 39.4 | 30.6 |

| 2 | 20.6 | 10.0 |

| 3 | 6.2 | 2.1 |

| 4 or more | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 |

More than 50% of patients with osteoarthritis had received a prescription for a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), and about one third had received a prescription for an opioid (Table 6). In addition, we found that 25% of patients had acetaminophen recorded in their medication list. However, this latter percentage may be underreported, because over-the-counter medications are not often captured in the EMR medication field.

Table 6: Use of medications among patients with osteoarthritis (n = 29 562).

| Drug class | Patients, no. (%) | Agent | Patients, no. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen (alone or in combination) | 7 424 | (25.1) | Acetaminophen alone | 4 725 | (16.0) |

| Acetaminophen in combination | 2 699 | (9.1) | |||

| NSAIDs | 16 732 | (56.6) | Celecoxib | 5 022 | (17.0) |

| Diclofenac* | 8 752 | (29.6) | |||

| Ibuprofen | 1 210 | (4.1) | |||

| Meloxicam | 1 963 | (6.6) | |||

| Naproxen | 5 885 | (19.9) | |||

| Other NSAIDs† | 3 023 | (10.2) | |||

| Narcotics | 9 761 | (33.0) | Codeine | 6 881 | (23.3) |

| Hydrocodone | 462 | (1.6) | |||

| Hydromorphone | 1 164 | (3.9) | |||

| Morphine | 784 | (2.7) | |||

| Oxycodone | 1 488 | (5.0) | |||

| Tramadol | 2 299 | (7.8) | |||

Note: NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. *There were 4 808 patients with prescriptions for diclofenac, about 45% of which were in the form of topical gel or cream. †Diflunisal, etodolac, floctafenine, flurbiprofen, indometacin, ketoprofen, ketorolac, lumiracoxib, nabumetone, piroxicam, rofecoxib, sulindac, tiaprofenic acid and valdecoxib.

Interpretation

In this retrospective cohort study of osteoarthritis prevalence, its associations with potential risk factors and drug treatment in primary care , we found 29 562 patients with an EMR that listed a diagnosis of osteoarthritis and a prevalence of the condition of 14.2%, which increased with age. Osteoarthritis was associated with both high and low BMI, and patients with COPD, depression, epilepsy and hypertension were at increased risk for this disease. Patients with osteoarthritis also showed an increased risk of multimorbidity.

The prevalence of osteoarthritis reported in previous research varies widely, because the estimates are dependent on the population sampled, the case definition of osteoarthritis and the joint involved.13,22,23 Previous Canadian studies focused on quantifying the burden of osteoarthritis and its association with other conditions, such as obesity and cardiovascular disease. Two studies that used data from the Canadian Community Health Survey evaluated arthritis and its association to other conditions: De Angelis and colleagues described arthritis (but did not specify osteoarthritis) and its association to obesity in patients 18 years of age and older, and found that obesity and female sex increase the risk of arthritis;7 Rahman and colleagues assessed osteoarthritis in patients aged 20 years and older and found that osteoarthritis was significantly associated with heart disease, angina and congestive heart failure in both men and women.9 In a study conducted in Manitoba, administrative data were used to determine the crude cross-sectional prevalence of osteoarthritis, and multiple arthritis algorithms were defined to determine the estimates.24 Some of the algorithms (physician billing, hospital billing and prescription data) produced estimates that were similar to those found in this study. In addition, we found prevalence estimates similar to those found in international studies, where prevalence estimates ranged from 16.4 to 42.6 per 1000 in the United Kingdom,25 were 23.2 per 1000 in the Netherlands26 and 35.3 per 1000 in an American study involving populations from England and Sweden.27

In primary care, osteoarthritis is both underdiagnosed and overdiagnosed.28,29 Many patients with joint pain who receive a diagnosis of osteoarthritis have no radiological confirmation of the condition. Alternatively, patients with osteoarthritis do not raise it as a concern with their physicians. We found estimates that were higher in both men and women compared with those found using administrative data.8,10 This result may be because cases are identified with billing data, which may be restricted to a single diagnostic code per visit, and osteoarthritis may not be recorded as the main reason for the visit. Another reason our estimates may be higher than other studies is the use of a case definition restricted to radiologically confirmed osteoarthritis.13 Finally, differences in osteoarthritis prevalence in self-report and surveys compared with our prevalence estimates from EMR data may be because patients over report joint pain as arthritis.

We found significant association of osteoarthritis with other chronic conditions, such as depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder and epilepsy. However, we found no association with diabetes, dementia or Parkinson disease. In addition, patients with osteoarthritis had increased multimorbidity. A study using primary care data in the UK also found extensive comorbidity with osteoarthritis, even after controlling for age, sex and socioeconomic status, but stated that propensity to consult may be a partial explanation for the results.30

Although NSAIDs were often prescribed in our study population, the number of patients with ibuprofen and naproxen recorded in their medication list was much lower, and the result was similar for acetaminophen. These drugs are available over the counter in Canada and therefore may not be recorded in the EMR. We also found that many patients with osteoarthritis were receiving opioids for pain, which is consistent with findings from UK primary care.31

Limitations

The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network is made up of a selected sample of family physicians who use EMRs. When compared with respondents of the 2010 National Physician Survey (NPS), CPCSSN practitioners were slightly younger and a higher proportion were women, but the geographic distribution of the practices were similar to that of the NPS.31,32 Misclassification error is a limitation of this study both in the diagnosis of osteoarthritis and medication prescription. We evaluated medications recorded at any time within the EMR, which includes medications prescribed before or after the diagnosis of osteoarthritis. In many cases, the EMR records lacked data on risk factors such as obesity and smoking, both of which were more commonly recorded among patients with osteoarthritis than among those without.

Conclusion

Osteoarthritis is a common disease in middle-aged and older Canadians attending primary care practitioners. It is more common in women than in men and is associated with comorbid conditions. Most people receive an anti-inflammatory or analgesic medication for their symptoms. Use of opioids for pain is common in this population. As the Canadian population ages, osteoarthritis will become an increasing burden for individuals and the health care system. Use of longitudinal EMR data is a useful approach for population surveillance of osteoarthritis.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/3/3/E270/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2163-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hootman JM, Helmick CG. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haq I, Murphy E, Dacre J. Osteoarthritis. Postgrad Med J 2003;79:377-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:26-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsiao CJ, Cherry DK, Beatty PC, et al. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 summary. Natl Health Stat Report 2010;3:1-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badley EM, Wang PP. Arthritis and the aging population: projections of arthritis prevalence in Canada 1991 to 2031. J Rheumatol 1998;25:138-44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Angelis G, Chen Y. Obesity among women may increase the risk of arthritis: observations from the Canadian Community Health Survey, 2007–2008. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:2249-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Berthelot JM, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of osteoarthritis in British Columbia, Canada. J Rheumatol 2007;34:386-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman MM, Kopek JA, Cibere J, et al. The relationship between osteoarthritis and cardiovascular disease in a population health survey: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarride JE, Haq M, O’Reilly DJ, et al. The excess burden of osteoarthritis in the province of Ontario, Canada. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1153-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gariepy G, Rossignol M, Lippman A. Characteristics of subjects self-reporting arthritis in a population health survey: distinguishing between types of arthritis. Can J Public Health 2009;100:467-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirdes JP, Poss JW, Caldarelli H, et al. An evaluation of data quality in Canada’s Continuing Care Reporting System (CCRS): secondary analyses of Ontario data submitted between 1996 and 2011. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira D, Peleteiro B, Araújo J, et al. The effect of osteoarthritis definition on prevalence and incidence estimates: a systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011;19:1270-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernatsky S, Lix L, O’Donnell S, et al. Consensus statements for the use of administrative health data in rheumatic disease research and surveillance. J Rheumatol 2013;40:66-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadhim-Saleh A, Green M, Williamson T, et al. Validation of the diagnostic algorithms for 5 chronic conditions in the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN): a Kingston Practice-based Research Network (PBRN) report. J Am Board Fam Med 2013;26:159-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williamson T, Green ME, Birtwhistle R, et al. Validating the 8 CPCSSN case definitions for chronic disease surveillance in a primary care database of electronic health records. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:367-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birtwhistle RV. Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network: a developing resource for family medicine and public health. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:1219-20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birtwhistle R, Keshavjee K, Lambert-Lanning A, et al. Building a pan-Canadian primary care sentinel surveillance network: initial development and moving forward. J Am Board Fam Med 2009;22:412-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williamson, T, Lambert-Lanning, A, Martin, K, et al. Primary health care intelligence: The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN)2013 annual report. Mississauga (ON): The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sibley LM, Moineddin R, Agha MM, et al. Risk adjustment using administrative data-based and survey-derived methods for explaining physician utilization. Med Care 2010;48:175-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson T, Eliasziw M, Hilton Fick G. Log-binomial models: exploring failed convergence. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2013;10:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manuel DG, Rosella LC, Stukel TA. Importance of accurately identifying chronic disease in studies using electronic health records. BMJ 2010;341:440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green ME, Hogg W, Johnston S, et al. Assessing methods for measurement of clinical outcomes and performance in primary care practices. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lix, L, Yogendran, M, Burchill, C, et al. Defining and validating chronic diseases: an administrative data approach. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jordan K, Clarke AM, Symmons DP, et al. Measuring disease prevalence: a comparison of musculoskeletal disease using four general practice consultation databases. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:7-14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westert GP, Schellevis FG, de Bakker DH, et al. Monitoring health inequalities through general practice: the Second Dutch National Survey of General Practice. Eur J Public Health 2005;15:59-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jordan KP, Jöud A, Bergknut C, et al. International comparisons of the consultation prevalence of musculoskeletal conditions using population-based healthcare data from England and Sweden. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:212-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson JL, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med 2003;139:575-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turkiewicz A, Gerdardsson de Verdier M, Engström G, et al. Prevalence of knee pain and knee OA in southern Sweden and the proportion that seeks medical care. Rheumatology 2015;54:827-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kadam UT, Jordan K, Croft PR. Clinical comorbidity in patients with osteoarthritis: a case–control study of general practice consulters in England and Wales. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:408-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edwards JJ, Jordan KP, Peat G, et al. Quality of care for OA: the effect of a point-of-care consultation recording template. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54:844-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Primary health care intelligence: 2013 progress report of the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN). Kingston (ON): Queen’s University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.National physician survey. Ottawa: College of Physicians of Canada and Canadian Medical Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.