Abstract

In 1996, 149 Florida manatees, Trichechus manatus latirostris, died along the southwest coast of Florida. Necropsy pathology results of these animals indicated that brevetoxin from the Florida red tide, Karenia brevis, caused their death. A red tide bloom had been previously documented in the area where these animals stranded. The necropsy data suggested the mortality occurred from chronic inhalation and/or ingestion. Inhalation theories include high doses of brevetoxin deposited/stored in the manatee lung or significant manatee sensitivity to the brevetoxin. Laboratory models of the manatee lungs can be constructed from casts of necropsied animals for further studies; however, it is necessary to define the breathing pattern in the manatee, specifically the volumes and flow rates per breath to estimate toxin deposition in the lung. To obtain this information, two captive-born Florida manatees, previously trained for husbandry and research behaviors, were trained to breathe into a plastic mask placed over their nares. The mask was connected to a spirometer that measured volumes and flows in situ. Results reveal high volumes, short inspiratory and expiratory times and high flow rates, all consistent with observed breathing patterns.

Introduction

Mortality trends of the Florida manatee, Trichechus manatus latirostris, suggest that prolonged exposures to the Florida red tide, Karenia brevis, may be one of their leading naturally occurring causes of death as illustrated in 1996, when 149 West Indian manatees died (Bossart et al., 1998; Landsberg and Steidinger, 1998). Pathology from these animals suggested chronic inhalation and/or ingestion of brevetoxins. Lesions were found in the upper respiratory tract, and immuno-histochemical demonstration suggests that a route of exposure is through inhalation (Bossart et al., 1998). Development of a method to study the breathing mechanics of live manatees could provide vital information of how the inhalation of red tide affects these animals. This information would allow for the creation of accurate laboratory models to better understand the deposition and dose of the red tide toxin in the manatee lung. In addition, this information would be useful to veterinary staff that administer anesthesia to injured manatees that require surgical intervention (personal communication, Dave Murphy, Lowry Park Zoo). This new technique for measuring lung mechanics may also be useful when applied to other marine mammals.

The anatomy of the manatee lung has been well studied on dead animals (Bergey, 1986). The airways have extensive cartilage reinforcement down to the terminal bronchioles that are consistent with many marine mammals. These reinforced airways are believed to be beneficial adaptations that assist in diving, however, manatees should not have a need for them, as they are not deep divers. Observations of manatee breathing patterns suggest that they have high tidal volumes and low breathing rates. Manatees may use high flow rates to move large volumes of air in a short period of time. It has been suggested that the manatee's residual volume (RV), or the amount of air remaining in the lung after a maximal exhalation, is very low when compared to total lung capacity (TLC) (Reynolds and Odell, 1991). To determine if this is so, vital capacity (VC), the maximal exhalation following a maximal inspiration (or TLC minus [RV]) must be measured.

Materials and Methods

To date, measurement of these parameters has been through simulation of spontaneous breathing on excised lungs from deceased animals. Unfortunately, lung compliance varies and is affected by the length of time since death (Bergey et al., 1987). This study presents a method to obtain lung volumes and flows from live West Indian manatees. Measurement of lung mechanics, specifically vital capacity (VC), peak expiratory flow rates (PEF), expiratory time (ET) and inspiratory vital capacity (IVC) were obtained on two male captive-born Florida manatees, Trichechus manatus latirostris, “Hugh”and “Buffett.” Hugh was approximately 554 kg and 14 years of age and Buffett was approximately 816 kg and 12 years of age when training for these behaviors was initiated. Both manatees had been trained husbandry and research behaviors previously (Colbert et al., 2001).

In-situ spirometry was obtained through training each animal to breath into a standard resuscitator mask that is typically used with adult humans. The mask, made of plastic, had an air cushion seal for comfort and optimal seal. Once each animal was reliably breathing in the mask, a spirometer (Spirometrics Flowmate LTE) was connected to it. The manatees were reinforced only if they waited for the mask to be correctly positioned over their nostrils and if they exhaled and inhaled into the mask. Manatee trainers determined the amount of time that was spent collecting these data for each session, however, a minimum goal of four breaths per manatee per session was set.

In the first segment of the study (January–April), the manatees were reinforced for all breaths captured by the spirometer. In the second segment of the study, the procedure was altered slightly so that each animal was only reinforced for breaths over 5 liters (L) (April and May). Once a minimum 5-L baseline was established, the third segment of the study was initiated. The goal of the third segment (June) was to determine the maximal flow rates and volumes for each animal. Here, the manatees were reinforced in a stair-step method such that they were only reinforced if they met increasingly greater thresholds. For example, if the first breath were a 5.2 L, the animal would have to achieve higher than a 5.2 on the next breath to be reinforced. If the next breath were a 6.5 L, the third breath would have to be higher than 6.5 L. Training of this manner will continue until the manatees reach a plateau that they cannot surpass. This stair step method will allow the research team to measure maximal effort by the animals and, therefore, measure a true vital capacity.

Spirometry ended on an arbitrary date to evaluate the data collected before continuing the research efforts.

Statistics

Superimposed on each plot is a fitted regression line. A nonparametric regression method was used in order not to impose a preconceived functional relationship. Here, five degrees of freedom allowed sufficient flexibility without undue roughness in the curve. Five degrees of freedom correspond, approximately, to a possibility of five changes of direction in the fitted curve (Green and Silverman, 1993).

Results and Discussion

Table 1 shows maximum values for each subject in each of the training segments. Values for Hugh (whose weight is 60% that of Buffett) are, in general, smaller. VC is measured on exhalation and is consistently larger than IVC. This is probably due to the trainers’ removing the mask prior to the end of inhalation.

Table 1.

Descriptive maximal values for Hugh and Buffett for each of the training segments.

| VC liters (L) | IVC (L) | PEF (L/sec) | PIF (L/sec) | Expiratory Time (sec) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUFFETT | |||||

| Segment 1 | 12.26 | 10.26 | 12.8 | 8.3 | 2.5 |

| Segment 2 | 17.81 | 13.67 | 12.2 | 9.7 | 4.0 |

| Segment 3 | 19.17 | 15.34 | 12.3 | 10.8 | 2.9 |

| HUGH | |||||

| Segment 1 | 10.66 | 11.15 | 13.7 | 8.8 | 3.0 |

| Segment 2 | 10.73 | 10.73 | 14.9 | 7.4 | 3.2 |

| Segment 3 | 11.48 | 11.92 | 14.4 | 8.0 | 2.3 |

Steidinger, K. A., J. H. Landsberg, C. R. Tomas, and G. A. Vargo (Eds.). 2004. Harmful Algae 2002. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Florida Institute of Oceanography, and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO.

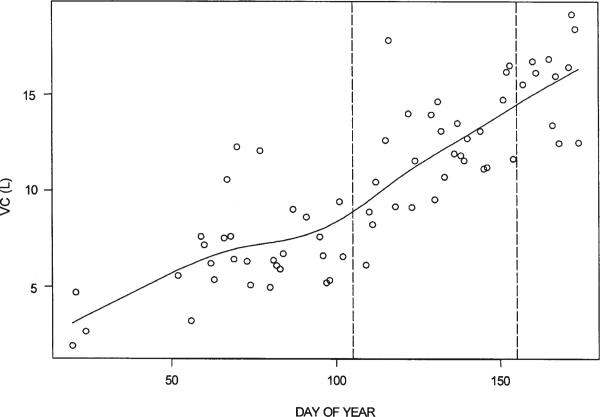

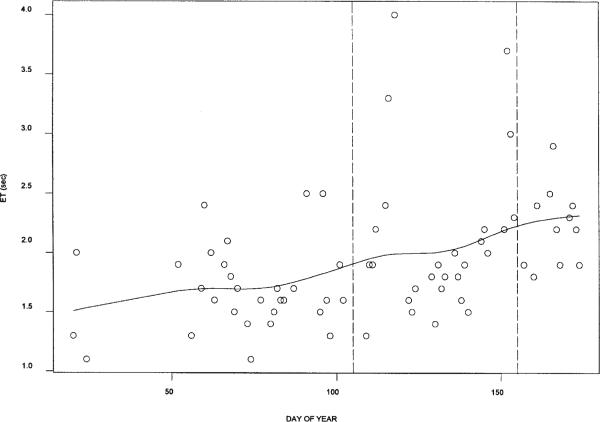

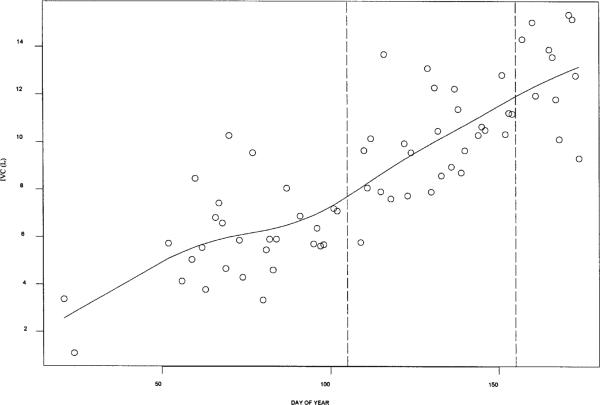

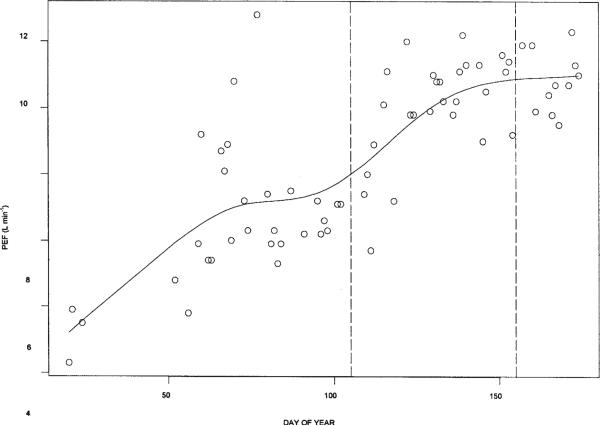

Plots of the maxima for each day are shown in Figures 1–4. Delineation of the three training segments is denoted by the vertical dashed line. For Buffett, the fitted regression line for each of the variables increased steadily through segments one and two, but then, for PEF, PIF and Expiratory Time, leveled off to some extent in segment three.

Figure 1.

Buffett, Maximum VC by Day.

Figure 4.

Buffett, Maximum ET by Day.

For Hugh, the curves of daily maxima rose, but then actually decreased during segment three for VC, IVC and PEF. Here, very low values of the maxima for each of these variables on the last day had a strong influence on the fitted curve. If the last day is omitted, then the curves instead flattened out, but did not decrease (not shown).

The flattening of some of the curves in the plots of daily maxima in segment three may indicate that the subjects (especially Hugh) were close to achieving consistent maximum effort in this segment.

For Buffett, the largest value of VC is 19.17 L (in segment three), and for Hugh, the largest value of VC is 11.48 L (also in segment three). It is interesting to note that the ratio of these largest values of VC to body weight (in kilograms) for each of these subjects is 0.021. A similar relationship between the maxima for the other variables and body weight was not seen, however.

Maximal expiratory flow rates more closely indicated maximal effort as a more flattened curve is seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Buffett, Maximum IVC by Day.

Discussion

Results from this study show that it is possible to measure the lung mechanics of a manatee. Since a vital capacity requires a maximal exhalation after a maximal inhalation, the results are dependent on the animal's effort, just as spirometry in the human is effort-dependent. Based on the results to date, a true vital capacity has not been reached. If vital capacity had been achieved, we would have expected the line shown in Figs. 1 and 2 to become flat. Further studies may provide maximal inspiratory and expiratory effort and allow for improved understanding of red tide aerosol toxin deposition in manatees.

Figure 3.

Buffett, Maximum PEF by Day.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P01 ES 10594).

References

- Bergey M. Lung Structure and Mechanics of the West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus). University of Miami; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bossart GD, Baden DG, Ewing RY, Roberts B, Wright SD. Toxicol. Pathol. 1998;26:276–282. doi: 10.1177/019262339802600214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert D, Fellner W, Bauer G, Manire C, Rhinehart H. Aquatic Mammals. 2001;27:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Green P, Silverman B. Nonparametric Regression and Generalized Linear Models. 1994;58:86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg J, Steidinger K. In: Harmful Algae. Reguera B, Blanco J, Fernández ML, Wyatt T, editors. Xunta de Galicia and IOC, UNESCO; 1998. pp. 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds JE, Odell D. Manatees and Dugongs. 1991:47–49. (Facts on File) [Google Scholar]