Abstract

BACKGROUND

The purpose of the present study was the analysis of the trends in case fatality rate of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in Isfahan, Iran. This analysis was performed based on gender, age groups, and type of AMI according to the International Classification of Diseases, version 10, during 2000-2009.

METHODS

Disregarding the Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease (MONICA), this cohort study considered all AMI events registered between 2000 and 2009 in 13 hospitals in Isfahan. All patients were followed for 28 days. In order to assess the case fatality rate, the Kaplan-Meier analysis, and to compare survival rate, log-rank test were used. Using the Cox regression model, 28 days case fatality hazard ratio (HR) was calculated.

RESULTS

In total, 12,900 patients with first AMI were entered into the study. Among them, 9307 (72.10%) were men and 3593 (27.90%) women. The mean age in all patients increased from 61.36 ± 12.19 in 2000-2001 to 62.15 ± 12.74 in 2008-2009, (P = 0.0070); in women, from 65.38 ± 10.95 to 67.15 ± 11.72 (P = 0.0200), and in men, from 59.75 ± 12.29 to 59.84 ± 12.54 (P = 0.0170),. In addition, the 28 days case fatality rate in 2000-2009 had a steady descending trend. Thus, it decreased from 11.20% in 2000-2001 to 07.90% in 2008-2009; in men, from 09.20% to 06.70%, and in women, from 16.10% to 10.90%. During the study, HR of case fatality rate in 2000-2001 declined; therefore, in 2002-2003, it was 0.93 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.77-1.11], in 2004-2005, 0.88 (95% CI = 0.73-1.04), in 2006-2007, 0.67 (95% CI = 0.56-0.82), and in 2008-2009, 0.69 (95% CI = 0.56-0.82).

CONCLUSION

In Isfahan, a reduction was observable in the trend of case fatality rate in both genders and all age groups. Thus, there was a 29.46% reduction in case fatality rate (27.17% in men, 32.29% in women) during the study period.

Keywords: Case Fatality Rate, Myocardial Infarction, Trend, Iran

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) remains one of the leading causes of death in both genders in developed countries.1 The incidence of mortality due to cardiovascular disease has been diminishing over the previous 3 decades in many developed countries.2 Reduced incidences, promotion of secondary prevention measures, use of new treatments during the acute phase, and improved survival after myocardial infarction (MI) have contributed to the declining mortality rates.3-5 However, MI is a primary cause of mortality and disability in the Iranian population.6 Age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, coronary history, acute MI (AMI) location, complications, treatments received during hospitalization and after hospital discharge, and the type of hospital are among the variables that may influence early or late mortality following an AMI.7-10

Most of the centers showed a decline in short-term case fatality rate, but the Isfahan center, Iran, did not.5 The purpose of the present study was the analysis of the trends of case fatality rate of AMI in Isfahan and Najafabad based on gender, age groups, and type of AMI in patients treated during 2000-2009. Type of AMI was determined according to the International Classification of Disease, version 10 (ICD10) and using streptokinase.

Materials and Methods

Isfahan is a city in the center of Iran, an Eastern Mediterranean country, and is the second largest city of Iran. Previous studies have shown a relatively high rate of cardiovascular risk factors in this industrial city.11-15

During the study period, about 13 hospitals were admitting and managing patients with CHD in Isfahan. More than 75% of patients who had experienced MI were managed in 4 public hospitals and the rest in the remaining 9 private hospitals. Except for military hospitals, which did not allow access to their patients’ records, other hospital records were evaluated. Among these hospitals, 4 were private and 9 public or university hospitals.16

In this registry, all possible CHD events were registered disregarding the Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease (MONICA) age limitation. In this study, the MONICA definition (non-fatal definite events and fatal definite or possible events) is used for MI events. Moreover, only first events and patients classified as one group according ICD10 are included.

The research team involved in the program consisted of cardiologists and general practitioners, a number of nurses trained in receiving and recording patients’ information, and professional biostatistician and epidemiologist. Identification and separation of patients with AMI based on ICD10 was performed by a cardiologist. Hospital discharge lists were used for case finding. Records of patients hospitalized in cardiology wards, coronary care units, or other wards but under the complete or partial supervision of cardiologists, were evaluated for possible signs and symptoms of CHD events. Basic information related to patients were collected by trained nurses, who used special forms to interview patients or obtained information from their hospital records. Symptoms and cardiac enzymes codes were classified in a manner similar to the MONICA project.17 They summarized accurate records in special checklists containing in-formation on age, sex, event and hospitalization dates, symptoms, history of previous MI, enzymes, admission electrocardiogram, whether the event was iatrogenic, survival status at discharge and after 28 days follow-up, and whether thrombolytic therapy was used during hospitalization. An expert nurse with special training in the MONICA registration system checked the filled records. Moreover, 10% of the checklists were randomly chosen and refilled by the expert nurse using the original hospital records and compared with those completed by registered nurses to see if any mistakes occurred. Then, data was collected from the Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Center (ICRC). As the center of Isfahan Province, MI patients who live in other cities of the province are also admitted to these hospitals. In order to calculate MI survival rate in Isfahan, only records from Isfahan and Najafabad city inhabitants were included in the study.16

A period of 28 days was used to define the case-fatality rate and to distinguish between events.18 All discharged MI patients were followed using telephone calls, and if not available, reached through their address. The patients or close family members were asked about patients’ health status. If a patient had died during the first 28 days after the event, death scenario was asked.16 Detailed descriptions of the methods used in this project have been provided in previous reports.16,19-24

Overall, 14,450 patients (10,334 men and 4116 women) with first AMI, who were inhabitants of Isfahan and Najafabad were entered into the study. Subsequently, 886 patients (564 men and 322 women) were excluded because their AMI type was not determined according to the ICD10. Furthermore, 118 patients (82 men and 36 women) were exclude from the study, because they died during the 28 days after the first attack without any sign of cardiovascular disease and due to accident, suicide, homicide, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, liver cirrhosis, rheumatic heart disease, vascular disease, or atherosclerosis. In addition, 418 patients (292 men and 126 women) were excluded because outcome was unknown. Moreover, 128 patients (89 men and 39 women) were excluded from the study, because the exact date of occurrence or death from the disease was not specified and the 28 days duration after the attack could not be calculated in these cases.17 Therefore, 12,900 patients, 9307 (72.15%) men and 3593 (27.85%) women, remained in the study.

The study period, from 2000 to 2009, was divided into 5 2-year periods (2000-2001, 2002-2003, 2004-2005, 2006-2007, and 2008-2009). Case fatality rates were adjusted for age through direct standardization. Standardization was based on 4 age groups; ≤ 40, 41-60, 61-80, and ≥ 81 years. In order to compare age average in the study, t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used. To assess the case fatality rate according to each period, Kaplan-Meier analysis, and to compare case fatality rate, log-rank test were used. Short-term (28 days) case fatality hazard ratio (HR) was calculated using the Cox regression model for every 2-year period. The first period (2000-2001) was considered as reference, and other periods were compared with this group and 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated. The trend of streptokinase use in the treatment of AMI in hospitals was evaluated in every 2-year period. SPSS software (version 15, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for data analysis. The significance value was set to P < 0.050.

Results

In total, this study included 12,900 fatal and non-fatal first AMI events, of which 9307 (72.15%) were men and 3593 (27.85%) women. Sex ratio (male/female) was 2.59. Patient’s demographic and clinical data is presented in table 1. The distribution of first AMI and 28 days case fatality rate in 10 years (for every 2 years separately) of the study periods is shown in table 2. Of the 12,900 patients with AMI entered into the study, 1198 died during the 28 days after their MI event (overall case fatality rate = 09.30% and survival rate = 90.70%). Of the 9307 men, 697 died (case fatality rate = 07.50% and survival rate = 92.50%) and of the 3593 women, 501 died (case fatality rate = 13.90% and survival rate = 86.10%) (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical data of hospitalized myocardial infarction (MI) patients in Isfahan

| Variables | Men |

Women |

Total |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live | Death | Total | Live | Death | Total | Live | Death | Total | |

| Age in men | |||||||||

| 39 year and lower | 427 | 98 | 525 | 336 | 114 | 450 | 763 | 212 | 975 |

| 40-49 | 394 | 5 | 399 | 42 | 2 | 44 | 436 | 7 | 443 |

| 50-59 | 1587 | 42 | 1629 | 225 | 11 | 236 | 1812 | 53 | 1865 |

| 60-69 | 2423 | 102 | 2525 | 579 | 48 | 627 | 3002 | 150 | 3152 |

| 70-79 | 2150 | 193 | 2343 | 933 | 123 | 1056 | 3083 | 316 | 3399 |

| 80 year and older | 1629 | 257 | 1886 | 977 | 203 | 1180 | 2606 | 460 | 3066 |

| Streptokinase | |||||||||

| Receiving | 4864 | 317 | 5181 | 1269 | 229 | 1498 | 6133 | 546 | 6679 |

| Not receiving | 3746 | 380 | 4126 | 1823 | 272 | 2095 | 5569 | 652 | 6221 |

| ICD, version 10 | |||||||||

| Acute sub endocardial MI | 2979 | 213 | 3192 | 950 | 126 | 1076 | 3929 | 339 | 4268 |

| Acute transmural MI of other sites | 2650 | 109 | 2759 | 825 | 86 | 911 | 3475 | 195 | 3670 |

| Acute transmural MI of inferior wall | 225 | 7 | 232 | 84 | 11 | 95 | 309 | 18 | 327 |

| Acute transmural MI of anterior wall | 82 | 24 | 106 | 28 | 25 | 53 | 110 | 49 | 159 |

| AMI, unspecified | 736 | 16 | 752 | 446 | 20 | 466 | 1182 | 36 | 1218 |

| Acute transmural MI of unspecified site | 1938 | 328 | 2266 | 759 | 233 | 992 | 2697 | 561 | 3258 |

| The first center was referred | |||||||||

| Non-specialized hospitals | 573 | 65 | 638 | 185 | 53 | 238 | 758 | 118 | 876 |

| Specialized hospital | 7547 | 590 | 8137 | 2747 | 418 | 3165 | 10294 | 1008 | 11302 |

| Unknown | 208 | 27 | 235 | 66 | 14 | 80 | 274 | 41 | 315 |

| Health networker clinic | 282 | 15 | 297 | 94 | 16 | 110 | 376 | 31 | 407 |

| Symptoms | |||||||||

| Typical | 7250 | 523 | 7773 | 2518 | 380 | 2898 | 9768 | 903 | 10671 |

| A typical | 993 | 92 | 1085 | 376 | 48 | 424 | 1369 | 140 | 1509 |

| Others | 339 | 75 | 414 | 183 | 69 | 252 | 522 | 144 | 666 |

| Miss | 28 | 7 | 35 | 15 | 4 | 19 | 43 | 11 | 54 |

| Cardiac enzymes | |||||||||

| A typical | 1026 | 61 | 1087 | 509 | 66 | 575 | 1535 | 127 | 1662 |

| Typical | 6597 | 483 | 7080 | 2196 | 306 | 2502 | 8793 | 789 | 9582 |

| Others | 780 | 45 | 825 | 291 | 43 | 334 | 1071 | 88 | 1159 |

| Not clear | 207 | 108 | 315 | 96 | 86 | 182 | 303 | 194 | 497 |

| Hospital | |||||||||

| Academic hospitals | 7894 | 650 | 8544 | 2842 | 465 | 3307 | 10736 | 1115 | 11851 |

| Privative hospitals | 716 | 47 | 763 | 250 | 36 | 286 | 966 | 83 | 1049 |

ICD: International Classification of Diseases; Cardiac enzymes: Lactate dehydrogenase, creatine kinase, and Troponin

Table 2.

Trend of case fatality rate of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) according to gender in Isfahan and Najafabad from 2000 to 2009

| Years | Total (n) | Number of events | Case fatality rate | HR of case fatality (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | ||||

| Overall | 9307 | 697 | 7.5 | - |

| 2000-2001 | 1331 | 123 | 9.2 | R |

| 2002-2003 | 1877 | 159 | 8.5 | 0.98 (0.74-1.30) |

| 2004-2005 | 2208 | 166 | 7.5 | 0.98 (0.75-1.29) |

| 2006-2007 | 2029 | 125 | 6.2 | 0.73 (0.54-0.98) |

| 2008-2009 | 1862 | 124 | 6.7 | 0.67 (0.49-0.91) |

| Women | ||||

| Overall | 3593 | 501 | 13.9 | - |

| 2000-2001 | 533 | 86 | 16.1 | R |

| 2002-2003 | 719 | 112 | 15.6 | 0.91 (0.72-1.15) |

| 2004-2005 | 893 | 139 | 15.6 | 0.81 (0.64-1.00) |

| 2006-2007 | 725 | 85 | 11.7 | 0.66 (0.51-0.84) |

| 2008-2009 | 723 | 79 | 10.9 | 0.71 (0.56-0.92) |

| Total | ||||

| Overall | 12900 | 1198 | 09.3 | - |

| 2000-2001 | 1864 | 209 | 11.2 | R |

| 2002-2003 | 2596 | 271 | 10.4 | 0.93 (0.77-1.11) |

| 2004-2005 | 3101 | 305 | 09.8 | 0.88 (0.73-1.04) |

| 2006-2007 | 2754 | 210 | 07.6 | 0.67 (0.56-0.82) |

| 2008-2009 | 2585 | 203 | 07.9 | 0.69 (0.57-0.84) |

R: Reference group; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval

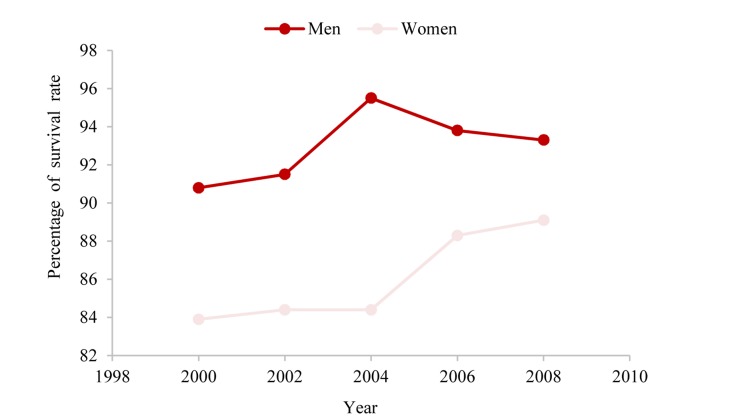

A steady descending trend was observed in the 28 days case fatality rate during the study period (2000-2009); it decreases from 11.82% in 2000-2001 to 07.90% in 2008-2009. In fact, we observed a 03.92% decrease in case fatality rate from 2000-2001 to 2008-2009, and 29.46% improvement in survival rate compared to 2000-2001. However, this trend has been in both genders. Therefore, in men, it decreased from 09.20% in 2000-2001 to 06.70% in 2008-2009 (meaning a 02.5% decrease in case fatality rate from 2000-2001 to 2008-2009 and 27.17% improvement in survival rate compared to 2000-2001). In women, it decreased from 16.10% in 2000-2001 to 10.90% in 2008-2009 (meaning a 05.20% decrease in case fatality rate from 2000-2001 to 2008-2009 and 36.80% improvement in survival rate compared to 2000-2001) (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trend of survival rate of acute myocardial infarction according to gender in Isfahan and Najafabad from 2000 to 2009

However, this trend was observed in HR of 28 days case fatality rate from AMI during the study period. Thus, in comparison with 2000-2001, in 2002-2003, 2004-2005, 2006-2007, and 2008-2009, HR was 0.93 (CI 95% = 0.77-1.11), 0.88 (CI 95% = 0.73-1.04), 0.67 (CI 95% = 0.56-0.82), and 0.69 (CI 95% = 0.56-0.82), respectively. This trend was observable in both genders. In men, HR, respectively, was 0.98 (CI 95% = 0.74-1.30), 0.95 (CI 95% = 0.75-1.29), 0.73 (CI 95% = 0.54-0.98), and 0.67 (CI 95% = 0.49-0.91). In women, it was 0.91 (CI 95% = 0.72-1.15), 0.8 (CI 95% = 0.64-1.00), 0.66 (CI 95% = 0.51-0.84), and 0.71 (CI 95% = 0.56-0.92), respectively (Table 2).

Mean age of all patients was 61.80 ± 12.60; in men it was 60.00 ± 12.50 and in women 66.72 ± 11.34. This difference was statically significant (P ≤ 0.0010). To examine changes in age of disease occurrence over time, the study period was divided into 5 2-year periods. Mean age of all patients increased from 61.36 ± 12.19 in the primary period (2000-2001) to 62.61 ± 12.81 in the final period (2008-2009). This difference was statically significant (P = 0.0070). There was a raising trend in mean age in men and women in the study period. For women, in the primary period, it was 65.38 ± 10.95 and in the final period was 67.15 ± 11.72 (P = 0.0200). For men, in the primary period, it was 59.75 ± 12.29 and in the final period 59.84 ± 12.54 (P = 0.0170) (Table 3). In addition, this trend was observed in mean age at time of death. Thus, in the primary period, it was 68.00 ± 10.60 and in the final period, 71.40 ± 9.53 (P = 0.0200). This trend was observed in men and women, but it was only significant in women. For women, in the primary period, it was 68.86 ± 10.41 and in the final period, 73.11 ± 08.94 (P = 0.0440). For men, in the primary period, it was 67.40 ± 10.73, and in the final period, 70.31 ± 08.70 (P = 0.1640) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Trend of change in mean age of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) at time of occurrence and death in Isfahan and Najafabad from 2000 to 2009

| Years | Number of men | Mean age in men | P | Number of women | Mean age in women | P | Number of patients | Mean age in patients | P | Sex ratio (men/women) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of disease occurrence | ||||||||||

| Overall | 9307 | 60.00 ± 12.54 | 0.017 | 3593 | 66.77 ± 11.37 | 0.020 | 12900 | 61.90 ± 12.60 | 0.007 | 2.59 |

| 2000-2001 | 1331 | 59.75 ± 12.29 | 533 | 65.38 ± 10.95 | 1864 | 61.36 ± 12.19 | 2.49 | |||

| 2002-2003 | 1877 | 59.77 ± 12.44 | 719 | 66.89 ± 11.14 | 2596 | 61.74 ± 12.51 | 2.61 | |||

| 2004-2005 | 2208 | 59.60 ± 12.59 | 893 | 66.62 ± 11.45 | 3101 | 61.62 ± 12.68 | 2.47 | |||

| 2006-2007 | 2029 | 60.13 ± 12.50 | 725 | 67.46 ± 11.34 | 2754 | 62.06 ± 12.63 | 2.79 | |||

| 2008-2009 | 1862 | 59.84 ± 12.54 | 723 | 67.15 ± 11.72 | 2585 | 62.61 ± 12.81 | 2.57 | |||

| Age in death time | ||||||||||

| Overall | 697 | 68.12 ± 11.15 | 0.164 | 501 | 71.46 ± 10.27 | 0.044 | 1198 | 69.52 ± 10.91 | 0.020 | 1.40 |

| 2000-2001 | 123 | 67.40 ± 10.73 | 86 | 68.86 ± 10.41 | 209 | 68.00 ± 10.60 | 1.43 | |||

| 2002-2003 | 159 | 67.16 ± 11.30 | 112 | 71.27 ± 10.58 | 271 | 68.86 ± 11.17 | 1.41 | |||

| 2004-2005 | 166 | 67.94 ± 11.20 | 139 | 71.40 ± 10.52 | 305 | 69.51 ± 11.00 | 1.19 | |||

| 2006-2007 | 125 | 68.13 ± 12.40 | 85 | 72.90 ± 10.12 | 210 | 70.06 ± 11.74 | 1.47 | |||

| 2008-2009 | 124 | 70.31 ± 8.70 | 79 | 73.11 ± 08.94 | 203 | 71.40 ± 09.53 | 1.56 |

Table 4 shows the trends of case fatality rate for each age group. Case fatality rate decreased in a steady pattern in all age groups with the increase in age. Consequently, there was a 60, 60, 19.31, and 46.75 percent reduction in case fatality rate in the final period (2008-2009), compared to the primary period (2000-2001), respectively, for < 40, 41-60, 61-80, and > 81 age groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Trend of case fatality rate of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) according to age groups in Isfahan and Najafabad from 2000 to 2009

| Age group (year) | < 40 |

41-60 |

61-80 |

> 81 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Death | Case fatality rate (%) | Patients | Death | Case fatality rate (%) | Patients | Death | Case fatality rate (%) | Patients | Death | Case fatality rate (%) | |

| Overall | 556 | 11 | 1.97 | 5323 | 225 | 4.2 | 6285 | 804 | 12.8 | 736 | 159 | 21.6 |

| 2000-2001 | 87 | 2 | 2.30 | 734 | 47 | 6.4 | 985 | 143 | 14.5 | 58 | 17 | 29.3 |

| 2002-2003 | 119 | 4 | 3.40 | 1048 | 56 | 5.3 | 1309 | 175 | 13.4 | 120 | 36 | 30.0 |

| 2004-2005 | 146 | 1 | 0.70 | 1333 | 59 | 4.4 | 1456 | 205 | 14.1 | 166 | 40 | 24.1 |

| 2006-2007 | 96 | 3 | 3.10 | 1163 | 36 | 3.1 | 1315 | 138 | 10.5 | 180 | 33 | 18.3 |

| 2008-2009 | 108 | 1 | 0.90 | 1045 | 26 | 2.5 | 1220 | 143 | 11.7 | 212 | 33 | 15.6 |

In this study, based on ICD10, AMI was classified into 6 groups; acute transmural MI of anterior wall, acute transmural MI of inferior wall, acute transmural MI of other site, acute transmural MI of unspecified site, acute sub endocardial MI and AMI, and unspecified. Because the number of patients in acute transmural MI of other sites and acute transmural MI of unspecified site was small and very unstable, we considered these two groups as one group. In Isfahan and Najafabad, based ICD10, from 2000 to 2009 no evident trend was observed in 10 years case fatality rate. However, difference in average case fatality rate between types of AMI, according to ICD10, was statistically significant (P < 0.0001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Trend of case fatality rate of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) according to type of AMI based on the International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD10) in Isfahan and Najafabad from 2000 to 2009

| AMI based ICD10 | Acute transmural MI of anterior wall |

Acute transmural MI of inferior wall |

Acute transmural MI of other sites and acute transmural MI of unspecified site |

Acute subendocardial MI |

unspecified AMI |

Total |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N (Death N) | Case fatality rate (%) | Total N (Death N) | Case fatality rate (%) | Total N (Death N) | Case fatality rate (%) | Total N (Death N) | Case fatality rate (%) | Total N (Death N) | Case fatality rate (%) | Total N (Death N) | Case fatality rate (%) | |

| Overall | 4268 (339) | 9.1 | 3670 (195) | 5.3 | 486 (67) | 13.8 | 1218 (36) | 3.0 | 3258 (561) | 17.2 | 12900 (1198) | 09.3 |

| 2000-2001 | 74 (69) | 9.5 | 602 (40) | 6.6 | 192 (46) | 24.0 | 200 (10) | 5.0 | 145 (44) | 30.3 | 1864 (209) | 11.2 |

| 2002-2003 | 94 (98) | 9.9 | 836 (60) | 7.2 | 90 (8) | 08.9 | 260 (6) | 2.3 | 416 (99) | 23.8 | 2596 (271) | 10.4 |

| 2004-2005 | 996 (75) | 5.0 | 888 (44) | 5.0 | 102 (6) | 05.9 | 269 (2) | 0.7 | 846 (178) | 21.0 | 3101 (305) | 09.8 |

| 2006-2007 | 762 (40) | 5.2 | 707 (30) | 4.2 | 74 (5) | 06.8 | 265 (7) | 2.6 | 946 (128) | 13.5 | 2754 (210) | 07.6 |

| 2008-2009 | 791 (57) | 7.2 | 637 (21) | 3.3 | 28 (2) | 07.1 | 24 (11) | 4.9 | 905 (112) | 12.4 | 2585 (203) | 07.9 |

AMI: Acute myocardial infarction; MI: Myocardial infarction; ICD10: International Classification of Diseases 10

In addition, use of streptokinase in the treatment service during the study period had no clear trend. In average, 51.8% (minimum of 48.3% and maximum of 56.40%) of patients received streptokinase, 55.70% in men (minimum of 52.20% and maximum of 61.80%) and 41.70% in women (minimum of 38.20% and maximum of 44.70%). Furthermore, 48.20% (minimum of 43.60% and maximum of 51.70%) of patients did not receive streptokinase; 47.80% in men (minimum of 38.20% and maximum of 47.80%) and 61.80% in women (minimum of 55.30% and maximum of 61.80%) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Trend of use of streptokinase in treatment of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) according to gender in Isfahan and Najafabad from 2000 to 2009

| Streptokinase | Men | Women | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving streptokinase [n (%)] | Not receiving streptokinase [n (%)] | Streptokinase total [n (%)] | Receiving streptokinase [n (%)] | Not receiving streptokinase [n (%)] | Streptokinase total [n (%)] | Receiving streptokinase [n (%)] | Not receiving streptokinase [n (%)] | Streptokinase total [n (%)] | |

| Overall | 5181 (55.7) | 4126 (47.8) | 9307 (100) | 1498 (41.7) | 2095 (58.3) | 3593 (100) | 6679 (51.8) | 6221 (48.2) | 12900 (100) |

| 2000-2001 | 823 (61.8) | 508 (38.2) | 1331 (100) | 229 (43.0) | 304 (57.0) | 533 (100) | 1052 (56.4) | 812 (43.6) | 1864 (100) |

| 2002-2003 | 1022 (54.4) | 855 (45.6) | 1877 (100) | 291 (40.5) | 428 (59.5) | 719 (100) | 1313 (50.6) | 1283 (49.4) | 2596 (100) |

| 2004-2005 | 1267 (57.4) | 941 (42.6) | 2208 (100) | 399 (44.7) | 494 (55.3) | 893 (100) | 1666 (53.7) | 1435 (47.3) | 3101 (100) |

| 2006-2007 | 1097 (54.1) | 932 (45.9) | 2029 (100) | 303 (41.8) | 422 (58.2) | 725 (100) | 1400 (50.8) | 1354 (49.2) | 2754 (100) |

| 2008-2009 | 972 (52.2) | 890 (47.8) | 1862 (100) | 276 (38.2) | 447 (61.8) | 723 (100) | 1248 (48.3) | 1337 (51.7) | 2585 (100) |

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated a consistent decrease in case fatality rate following a first MI in Isfahan, during a 10 years period from 2000 to 2009. The decreasing trend of case fatality rate was observable in both genders and all age groups. There was a 29.46% reduction in case fatality rate in the final period (2008-2009) compared with the primary period (2000-2001). A 27.17% decrease was observed in men, and 32.29% in women. Moreover, a 60% decrease in the ≤ 40 age group, 60% in 41-60 age group, 19.31% in 61-80, and 46.75% in ≥ 80 was observed. In addition, in the duration of the study, there was a decreasing trend in the HR of 28 days case fatality rate in all patients.

In this study, the majority of patients were men (72.10% men and 27.90% women) and women were older (66.77 ± 11.37 vs. 60.00 ± 12.54 years; P < 0.0010). The 28 days case fatality rate was higher in women than men (13.90 vs. 07.50%; < 0.0001). In a study conducted by Carine Milcent et al. in the French Hospitals Database, most patients were men (70% men and 30% women) and women were older (75 vs. 63 years of age; P < 0.0010) and had a higher rate of hospital mortality (14.80 vs. 06.10%; P < 0.0001) than men.25 This was in agreement with the findings of the current study. However, the present analysis confirms the higher 28 days case fatality rate from AMI in women; the so-called “gender gap” reported in other studies.26-29 In previous studies, we observed that crude hospital mortality rates for AMI in women was higher than men. This difference may be partly due to the higher average age of women at the time of disease occurrence and higher prevalence of comorbidities in women compared with men.26 More frequent use of revascularization procedures in men may also account for the fewer deaths. Indeed, men with AMI tend to undergo more aggressive hospital treatments than women.30,31 We observed a similar result in the Iranian treatment system; during the study, an average higher proportion of men received streptokinase than women (55.70% men and 41.70% women). However, the impact of lower rates of revascularization is controversial. In some studies, older age and higher baseline risk are presented as the causes of higher rates of mortality in women.32,33 In addition, some studies inferred that treatment in women had no effect on short-term survival from AMI.27,34 Case fatality rate of AMI in 2008-2009 was 29.46% less than in 2000-2001 (in men 27.17% and in women 32.29%), which coincides with the results of other hospital registered studies.35-37 HR of 28 days case fatality rate of AMI in 2008-2009 was 0.69 (95% CI = 0.56-0.82) compared with 2000-2001; for men and women, it was 0.63 (95% CI = 0.45-0.88) and 0.70 (95% CI = 0.54-0.90), respectively. A similar result was obtained in a European register on acute coronary syndrome, that compared 30 days mortality in 2000 and 2004 [odds ratio (OR) = 0.85 (0.73-0.99)].38 In the study by MacIntyre et al., 28 days case fatality rate increased with increasing of age.39 However, in this study, with the rising trend in mean age in the disease occurrence a steady decline was observed in case fatality rate. It is evident that the severity of infarctions decreased over time. A hypothesis is that the increasing use of medications such as aspirin and β-blockers before admission may reduce the size and severity of infarctions.40 Therefore, over time this could be effective in reducing the AMI case fatality rate.

Population-based studies all documented a favorable decline in early mortality among younger individuals contrasting with a persistently high fatality rate among the elderly over a period of time ranging from 1975 to 1995.2,41-44 More importantly, the mortality rate of infarction in the community remained high and was consistently higher than that reported in clinical trials, reflecting their inherent selection processes.45 Although only clinical trials can test the efficacy of a new treatment, reports from community surveillance present important complementary insights into the effectiveness of care and treatments once implement. The current study demonstrates that the marked improvement in early fatalities after MI persisted over time and that notable survival gains were realized among the women and elderly, in whom discrepancy had been detected previously.43 This article was conducted based on the MONICA project in Isfahan with the support and ethical approval of ICRC with the code 84130, in year 2012.

Limitations

A difficulty of this study is a lack of complete, community-based case ascertainment, which includes protocols for finding community fatal and non-fatal MI cases who are not admitted to hospitals. Most important limitation of the study is the lack of data about out-of-hospital fatal cases, such as MI cases managed at home or in health centers. This figure might be unimportant since MI event is considered an emergency in the Iranian health care system, and all hospitals should admit such patients regardless of their insurance status. In the Danish MONICA population, this figure was measured to be > 01% of total MI cases in a year.46 Therefore, omitting these patients will not lead to a sham decline in MI case fatality rates.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated a consistent decrease in case fatality rate following a first MI in Isfahan, during a 10-year period from 2000 to 2009. The decrease in the trend of case fatality rate in both genders and all age groups was observable. There was 29.46% reduction in case fatality rate in the final period (2008-2009) compared to the primary period (2000-2001); 27.17% in men and 32.29% in women. A 60%, 60%, 19.31%, and 46.75% reduction was observed in the ≤ 40 years, 41-60 years, 61-80 years, and ≥ 80 years age groups, respectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank off all Isfahan Cardiovascular Research Institute Staff who helped in this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allender S, Scarborough P, Peto V, Rayner M, Leal J, Luengo-Fernandez R, et al. European cardiovascular disease statistics. 3rd. Brussels, Belgium: A European Heart Network; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosamond WD, Chambless LE, Folsom AR, Cooper LS, Conwill DE, Clegg L, et al. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction and in mortality due to coronary heart disease, 1987 to 1994. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(13):861–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809243391301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGovern PG, Pankow JS, Shahar E, Doliszny KM, Folsom AR, Blackburn H, et al. Recent trends in acute coronary heart disease--mortality, morbidity, medical care, and risk factors. The Minnesota Heart Survey Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(14):884–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604043341403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botkin NF, Spencer FA, Goldberg RJ, Lessard D, Yarzebski J, Gore JM. Changing trends in the long-term prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction: a population-based perspective. Am Heart J. 2006;151(1):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Mahonen M, Tolonen H, Ruokokoski E, Amouyel P. Contribution of trends in survival and coronary-event rates to changes in coronary heart disease mortality: 10-year results from 37 WHO MONICA project populations. Monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 1999;353(9164):1547–57. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatmi ZN, Tahvildari S, Gafarzadeh MA, Sabouri KA. Prevalence of coronary artery disease risk factors in Iran: a population based survey. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2007;7:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-7-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bueno H. Clinical prediction of the early prognosis in acute myocardial infarct. Rev Esp Cardiol. 1997;50(9):612–27. doi: 10.1016/s0300-8932(97)73273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heras M, Marrugat J, Aros F, Bosch X, Enero J, Suarez MA, et al. Reduction in acute myocardial infarction mortality over a five-year period. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006;59(3):200–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reina A, Colmenero M, Aguayo de, Aros F, Marti H, Claramonte R, et al. Gender differences in management and outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2007;116(3):389–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briffa T, Hickling S, Knuiman M, Hobbs M, Hung J, Sanfilippo FM, et al. Long term survival after evidence based treatment of acute myocardial infarction and revascularisation: follow-up of population based Perth MONICA cohort, 1984-2005. BMJ. 2009;338:b36. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talaei M, Sadeghi M, Mohammadifard N, Shokouh P, Oveisgharan S, Sarrafzadegan N. Incident hypertension and its predictors: the Isfahan Cohort Study. J Hypertens. 2014;32(1):30–8. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32836591d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadeghi M, Talaei M, Parvaresh RE, Dianatkhah M, Oveisgharan S, Sarrafzadegan N. Determinants of incident prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in a 7-year cohort in a developing country: The Isfahan Cohort Study 72. J Diabetes. 2015;7(5):633–41. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sadeghi M, Talaei M, Oveisgharan S, Rabiei K, Dianatkhah M, Bahonar A, et al. The cumulative incidence of conventional risk factors of cardiovascular disease and their population attributable risk in an Iranian population: The Isfahan Cohort Study. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:242. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.145749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gharipour M, Sarrafzadegan N, Sadeghi M, Andalib E, Talaie M, Shafie D, et al. Predictors of metabolic syndrome in the Iranian population: waist circumference, body mass index, or waist to hip ratio? Cholesterol. 2013;2013:198384. doi: 10.1155/2013/198384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talaei M, Sarrafzadegan N, Sadeghi M, Oveisgharan S, Marshall T, Thomas GN, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular diseases in an Iranian population: the Isfahan Cohort Study. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16(3):138–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sarrafzadegan N, Oveisgharan Sh, Toghianifar N, Hosseini Sh, Rabiei K. Acute myocardial infarction in Isfahan, Iran: hospitalization and 28th day case-fatality rate. ARYA Atheroscler. 2009;5(3):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO MONICA. The world health organization monica project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): A major international collaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1988;41(2):105–14. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahonen M, Tolonen H, Kuulasmaa K. MONICA Coronary Event Registration Data Book 1980-1995. Helsinki, Finland: MONICA Data Centre,National Public Health Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Sarrafzadegan N, Baradaran HR, Hosseini Sh, Asadi-Lari M. Short-Time Survival Rate of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Elderly Patients in Isfahan City, Iran. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2014;32(303):1585–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammadian Hafshejani, Sarrafzadegan N, Baradaran Attar, Hosseini Sh. Gender Difference in Determinants of Short-Term Survival of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction in Isfahan, Iran. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2012;30(209):16110–1622. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Sarrafzadegan N, Hosseini S, Baradaran HR, Roohafza H, Sadeghi M, et al. Seasonal pattern in admissions and mortality from acute myocardial infarction in elderly patients in Isfahan, Iran. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014;10(1):46–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadian Hafshejani, Baradaran Attar, Sarrafzadegan N, Bakhsi Hafshejani, Hosseini S, AsadiLari M, et al. Evaluation of short-term survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction and the differences between the sexes in Isfahan and Najaf Abad between 1998-2008. Razi j Med Sci. 2012;19(95):25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammadian Hafshejani, Baradaran H, Sarrafzadegan N, Asadi Lari, Ramezani A, Hosseini S, et al. Predicting factors of Short-term Survival in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction in Isfahan Using a Cox Regression Model. Iran J Epidemiol. 2012;8(2):39–47. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Baradaran-AttarMoghaddam H, Sarrafzadegan N, AsadiLari M, Roohani M, Allah-Bakhsi F, et al. Secular trend changes in mean age of morbidity and mortality from an acute myocardial infarction during a 10-year period of time in Isfahan and Najaf Abad. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2013;14(6):101–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milcent C, Dormont B, Durand-Zaleski I, Steg PG. Gender differences in hospital mortality and use of percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: microsimulation analysis of the 1999 nationwide French hospitals database. Circulation. 2007;115(7):833–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM, Berkman LF, Horwitz RI. Sex differences in mortality after myocardial infarction. Is there evidence for an increased risk for women? Circulation. 1995;91(6):1861–71. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.6.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gan SC, Beaver SK, Houck PM, MacLehose RF, Lawson HW, Chan L. Treatment of acute myocardial infarction and 30-day mortality among women and men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(1):8–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007063430102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marrugat J, Sala J, Masia R, Pavesi M, Sanz G, Valle V, et al. Mortality differences between men and women following first myocardial infarction. RESCATE Investigators. Recursos Empleados en el Sindrome Coronario Agudo y Tiempo de Espera. JAMA. 1998;280(16):1405–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.16.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koek HL, de BA, Gast F, Gevers E, Kardaun JW, Reitsma JB, et al. Short- and long-term prognosis after acute myocardial infarction in men versus women. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(8):993–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsui K, Fukui T, Hira K, Sobashima A, Okamatsu S, Hayashida N, et al. Impact of sex and its interaction with age on the management of and outcome for patients with acute myocardial infarction in 4 Japanese hospitals. Am Heart J. 2002;144(1):101–7. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chandra NC, Ziegelstein RC, Rogers WJ, Tiefenbrunn AJ, Gore JM, French WJ, et al. Observations of the treatment of women in the United States with myocardial infarction: a report from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction-I. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(9):981–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.9.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kudenchuk PJ, Maynard C, Martin JS, Wirkus M, Weaver WD. Comparison of presentation, treatment, and outcome of acute myocardial infarction in men versus women (the Myocardial Infarction Triage and Intervention Registry). Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bueno H, Vidan MT, Almazan A, Lopez-Sendon JL, Delcan JL. Influence of sex on the short-term outcome of elderly patients with a first acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;92(5):1133–40. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaccarino V, Horwitz RI, Meehan TP, Petrillo MK, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in mortality after myocardial infarction: evidence for a sex-age interaction. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(18):2054–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.18.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox KA, Steg PG, Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Anderson FA, Granger CB, et al. Decline in rates of death and heart failure in acute coronary syndromes, 1999-2006. JAMA. 2007;297(17):1892–900. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.17.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers WJ, Frederick PD, Stoehr E, Canto JG, Ornato JP, Gibson CM, et al. Trends in presenting characteristics and hospital mortality among patients with ST elevation and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008;156(6):1026–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, Bertel O, Rickli H, Gaspoz JM. Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results on 20,290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart. 2007;93(11):1369–75. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandelzweig L, Battler A, Boyko V, Bueno H, Danchin N, Filippatos G, et al. The second Euro Heart Survey on acute coronary syndromes: Characteristics, treatment, and outcome of patients with ACS in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin in 2004. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(19):2285–93. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.MacIntyre K, Stewart S, Capewell S, Chalmers JW, Pell JP, Boyd J, et al. Gender and survival: a population-based study of 201,114 men and women following a first acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(3):729–35. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Col NF, Yarzbski J, Gore JM, Alpert JS, Goldberg RJ. Does aspirin consumption affect the presentation or severity of acute myocardial infarction? Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(13):1386–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGovern PG, Jacobs DR, Shahar E, Arnett DK, Folsom AR, Blackburn H, et al. Trends in acute coronary heart disease mortality, morbidity, and medical care from 1985 through 1997: the Minnesota heart survey. Circulation. 2001;104(1):19–24. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.104.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldberg RJ, Samad NA, Yarzebski J, Gurwitz J, Bigelow C, Gore JM. Temporal trends in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1162–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roger VL, Jacobsen SJ, Weston SA, Goraya TY, Killian J, Reeder GS, et al. Trends in the incidence and survival of patients with hospitalized myocardial infarction, Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979 to 1994. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):341–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roger VL, Weston SA, Gerber Y, Killian JM, Dunlay SM, Jaffe AS, et al. Trends in incidence, severity, and outcome of hospitalized myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121(7):863–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.897249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Steg PG, Lopez-Sendon J, Lopez de, Goodman SG, Gore JM, Anderson FA, et al. External validity of clinical trials in acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(1):68–73. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kark JD, Goldberger N, Fink R, Adler B, Kuulasmaa K, Goldman S. Myocardial infarction occurrence in Jerusalem: a Mediterranean anomaly. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178(1):129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]