Abstract

Psychotic disorders continue to be among the most disabling and scientifically challenging of all mental illnesses. Accumulating research findings suggest that the etiologic processes underlying the development of these disorders are more complex than had previously been assumed. At the same time, this complexity has revealed a wider range of potential options for preventive intervention, both psychosocial and biological. In part, these opportunities result from our increased understanding of the dynamic and multifaceted nature of the neurodevelopmental mechanisms involved in the disease process, as well as the evidence that many of these entail processes that are malleable. In this article, we review the burgeoning research literature on the prodrome to psychosis, based on studies of individuals who meet clinical high risk criteria. This literature has examined a range of factors, including cognitive, genetic, psychosocial, and neurobiological. We then turn to a discussion of some contemporary models of the etiology of psychosis that emphasize the prodromal period. These models encompass the origins of vulnerability in fetal development, as well as postnatal stress, the immune response, and neuromaturational processes in adolescent brain development that appear to go awry during the prodrome to psychosis. Then, informed by these neurodevelopmental models of etiology, we turn to the application of new research paradigms that will address critical issues in future investigations. It is expected that these studies will play a major role in setting the stage for clinical trials aimed at preventive intervention.

Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders remain among the most severe and debilitating mental disorders, and although current pharmacologic treatments usually reduce symptom severity, they do little to remediate the associated functional impairment. Thus, schizophrenia ranks among the top 10 causes of disability in developed countries worldwide (Murray & Lopez, 1996). Adding to the functional challenges of coping with a serious mental illness is that the modal age at onset of psychosis is late adolescence/early adulthood. There is usually a gradual decline in functioning that begins during the teen years, with an accompanying gradual emergence of psychotic symptoms. Patients and their family members are therefore confronted with the onset of a serious mental illness during a developmental stage when the expectation is for increasing functional autonomy.

That adolescence is a critical period for the onset of psychosis has also served to alert investigators to the importance of this developmental stage in the search for etiologic mechanisms. This notion has been partly fueled by advances in scientific technologies for studying human brain development in vivo. The application of neuroimaging and other technologies has revealed significant normative changes in brain structure and function during adolescence and early adulthood (Bramen et al., 2011). Abnormalities in these neurodevelopmental processes are now viewed as possible mechanisms underlying the emergence of psychotic symptoms. As a result, investigators have begun to intensify their focus on the period preceding the modal age at onset of psychosis.

As noted, there is a gradual functional decline and symptom onset, now referred to as the prodrome, that typically begins several months to several years before the first episode of psychosis (Addington & Heinssen, 2012). Interest in this period has grown not only because it may hold the greatest promise for identifying neural mechanisms but also because it may offer the best opportunities for preventive intervention. Although some may view the latter goal as elusive, there is a growing consensus among investigators that it may be within our grasp.

In this article, we begin with an overview of our current scientific understanding of the varied manifestations of the psychosis prodrome, including results from a multisite longitudinal study of individuals at clinical high risk (CHR), the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS; Cannon et al., 2008). Informed by these findings, we then explore models of the neurodevelopmental processes involved in the emergence of psychosis. Integrating the elements from various models suggests that complex and varied neural mechanisms can give rise to psychosis. Finally, we will consider some of the promising future directions in research in this area, with an emphasis on paradigms that have the potential to elucidate dynamic processes in brain structure and function and to inform future efforts at preventive intervention.

The Nature of Psychotic Disorders

Prior to discussing the prodrome, some recent changes in scientific conceptualizations of psychosis should be mentioned. Diagnostic taxonomies for mental disorders, such as the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), draw explicit diagnostic boundaries among the various psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders, and depression and bipolar disorder with psychotic features. However, numerous research findings indicate that no genetic risk factor is specific to a single DSM category of psychotic disorder. It instead appears that genetic factors confer nonspecific vulnerability for psychosis, with no single gene or allele having a major impact on risk status (O’Donovan, Craddock, & Owen, 2009). Thus, the diagnostic boundaries we have drawn on the basis of observed phenomenology may reflect the moderating effects of various genetic and environmental factors. Bioenvironmental risk factors, such as pre-natal complications and cannabis use in young adulthood, also appear to be nonspecific, in that they are associated with heightened risk for both nonaffective and affective psychoses (Markham & Koenig, 2011; Moore et al., 2007).

With respect to genetics, contemporary research findings also highlight the importance of spontaneous or de novo mutations (i.e., not present in the biological mother or father) in the etiology of psychosis and even cast doubt on the notion of discrete psychosis spectrum and autism spectrum disorders. Molecular genetic technologies have shown that de novo mutations, especially copy number variants are more common than previously assumed and that they are present at a significantly higher rate in individuals with psychiatric disorders (Addington & Rapoport, 2012). Moreover, some of the same mutations observed in autism spectrum disorders are also more common in individuals with psychotic disorders (Kong et al., 2012).

Another important advance in genetics is the burgeoning field of epigenetics, which is the study of potentially heritable changes in gene expression that are not due to changes in DNA sequence but instead influence protein messengers (Hunter, 2012). These changes in gene expression, or epigenetic modifications, are a consequence of a range of environmental factors and internal processes, including hormones levels, and can result in changes in brain structure that have the potential to be permanent. There is increasing evidence that epigenetic mechanisms are involved in the brain changes that occur during normal adolescent development in response to hormones (Charmandari, Kino, Souvatzoglou, & Chrousos, 2003; La-douceur, Peper, Crone, & Dahl, 2012; Peper, Hulshoff Pol, Crone, & van Honk, 2011; Trotman et al., in press). Although the study of epigenetics in psychotic disorders is in its infancy, there are now several published reports showing that epigenetic profiles differentiate psychotic patients from controls, including their healthy monozygotic cotwins (Dempster et al., 2011; Furrow, Christiansen, & Feldman, 2011).

In the domain of psychosocial risk factors, the nonspecific effects are also well documented. In particular, stress and trauma have been linked with risk for mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders, as well as many nonpsychiatric disorders (Davidson & McEwen, 2012; Walker, Mittal, & Tessner, 2008). Further, there is evidence that similar neurobiological processes may be involved in the adverse effects of stress exposure on vulnerability to all these diagnostic categories. Thus, activation of biological stress systems, especially the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, may trigger the expression of varied symptoms and syndromes, depending on the nature of latent vulnerabilities in brain neural circuitry.

In light of the above, the present discussion will use the terms psychoses or psychotic disorders to refer to the spectrum of psychoses, with schizophrenia at the severe end and mood disorders with transient and less severe psychotic symptoms at the mild end. This is not intended to imply that there are no etiologic subtypes of psychosis but rather that valid diagnostic boundaries among them, based on etiologic factors, have not yet been documented.

The Prodrome to Psychosis

The results from decades of research have led most investigators to assume that vulnerability to psychosis is usually congenital in origin and that both genetic and prenatal factors set the stage (Walker, 1994; Weinberg, Jenkins, Marazita, & Maher, 2007). Nonetheless, because it is uncommon for psychosis to have its onset before age 15 or after age 40, it is also clear that developmental processes are important in modulating the expression of vulnerability. These developmental constraints give rise to a critical risk period for the onset of the prodrome to psychosis in adolescence/young adulthood.

Retrospective and prospective studies have shown that the prodrome can last from months to years prior to the clinical onset of psychotic symptoms (Addington & Heinssen, 2012; Cannon et al., 2008; Niendam, Jalbrzikowski, & Bearden, 2009). During this stage, attenuated positive psychotic symptoms, such as increasing suspiciousness, unusual ideas, and abnormal perceptual experiences, begin to emerge. Functional decline in social, academic, and occupational domains also characterizes this phase. Thus, by definition, prodromal syndromes are subclinical manifestations of the perceptual, ideational, and behavioral symptoms of psychosis. In the research literature, these syndromes are referred to as CHR, “ultrahigh risk,” or prodromal. Because prodromal may be taken to imply the inevitability of a subsequent illness, we use CHR to refer to individuals who are manifesting putative prodromal syndromes.

Given that the prodromal phase may be the optimal period for identifying neuropathological processes and, ultimately, for preventive intervention, several structured approaches for prospective assessment of prodromal syndromes have been developed (Addington & Heinssen, 2012; Correll, Hauser, Auther, & Cornblatt, 2010) These structured interviews yield symptom ratings and utilize standard thresholds for designating CHR status. In the United States, the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (Miller et al., 2003) has been the most widely used measure; like other prodrome assessment tools, it measures subclinical positive (e.g., suspiciousness, unusual ideas and perceptual experiences) and negative (e.g., social withdrawal, decreased emotional expression and role functioning) symptoms, as well as mood and vegetative symptoms. Using these measures to identify CHR samples enhances positive predictive power above the population prevalence of 1%–2%, as well as the risk rate (i.e., about 12%) for first-degree relatives of psychosis patients (Sorensen, Mortensen, Reinisch, & Mednick, 2009). Among those who meet criteria for CHR status based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes, the rate of subsequent “conversion” to psychosis is between 25% and 35% within 2 to 4 years (Cannon et al., 2008). Currently ongoing prospective CHR studies are aimed at boosting predictive power beyond this level and elucidating neural mechanisms involved in the emergence of psychosis. In pursuit of these goals, the NAPLS project is the largest of such investigation in the United States and is tracking biobehavioral development in CHR individuals (Cannon et al., 2008).

There are advantages of research on CHR samples as opposed to individuals who are diagnosed with a psychotic disorder. First, this line of investigation offers opportunities for identifying mechanisms subserving the emergence of psychosis and therefore potential targets for preventive intervention. Second, because most who meet CHR diagnostic criteria have not yet received antipsychotic medication, the problem of medication confounds is reduced. This is important for studying neurobiological processes.

In the overview of findings from CHR research, some caveats should be noted. First, that the predictive power of prodromal syndromes will be expected to vary as a function of the mean age and distribution of ages in the CHR sample; the risk rate for psychosis onset peaks in the early 20s and begins to decline after age 30. Thus, the duration of the follow-up period, in combination with the proportion of CHR participants in the lower (e.g., under 20) and upper (over 30) end of the modal risk period, will influence the conversion rate and positive predictive power. Second, there is a large body of literature on DSM schizotypal personality disorder (SPD); current criteria for the prodrome overlap with the diagnostic criteria for SPD, which is known to be linked with an increased subsequent risk for psychosis (Asarnow, 2005; Shapiro, Cubells, Ousley, Rockers, & Walker, 2011; Woods et al., 2009). A review of the research findings on SPD is beyond the scope of this paper, but it is worth noting that the results generally parallel those yielded by research on CHR samples.

In the following sections, we summarize research findings on CHR individuals, with an emphasis on the factors that predict conversion to psychosis. As the findings accumulate, it is increasingly apparent that CHR syndromes are associated with deficits and abnormalities similar to those observed in diagnosed psychotic patients.

Cognitive Functions and CHR for Psychosis

Cognitive impairment is generally considered a core feature of psychotic disorders, and recent meta-analyses have documented impairment in psychosis patients on a range of functions, including verbal memory and fluency, executive functions, working memory, and sustained attention (Bora, Yucel, & Pantelis, 2010; Mesholam-Gately, Giuliano, Goff, Faraone, & Seidman, 2009). However, there is inter- and intrapatient variability, with some evidence of cognitive decline following the initial onset of clinical symptoms (Palmer, Dawes, & Heaton, 2009). As research findings on CHR samples accumulate, similar trends are apparent. For example, a recent meta-analysis (Giuliano et al., 2012) showed that CHR samples manifest cognitive impairments in most domains when compared with healthy controls. Among the functions that distinguished CHR participants from controls were general cognitive ability, language functions, verbal memory, attention, visual–spatial abilities, working memory, and executive functioning. Further, CHR participants who convert to psychosis have more pronounced deficits at baseline than those who do not, albeit less severe deficits than first-episode psychotic patients (Seidman et al., 2010).

Psychotic disorders are also associated with a range of deficits in social cognitive abilities. Included among these are impairments in attributional bias, emotion perception, social perception, and theory of mind (ToM; Green et al., 2008). An emerging body of evidence demonstrates similar, though less severe, deficits in CHR individuals (Thompson, Bartholomeusz, & Yung, 2011). For example, one study compared CHR, first episode of psychosis, and chronic patients with matched healthy controls (Green et al., 2012). The investigators found impairment in social problem solving, emotion recognition and ToM in all three clinical groups relative to controls. In addition, a recent prospective study revealed that CHR participants who converted to psychosis were more impaired on social cognitive tasks, including ToM, than nonconverters (Kim et al., 2011). When controlling for general cognitive abilities, impaired ToM was independently associated with shorter time to psychosis transition, suggesting that social cognitive deficits that precede psychosis are not solely attributable to general cognitive factors.

Psychosocial Stress and Trauma

Contemporary models of the etiology of psychosis assume that psychosocial stress plays a role in triggering the expression of vulnerability. To date, there is no consistent evidence from cross-sectional studies that patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and other psychoses experience more stressful life events than healthy or psychiatric controls; however, several longitudinal designs have revealed a significant increase in the number of life events preceding psychotic relapse (Phillips, Francey, Edwards, & McMurray, 2007; Walker et al., 2008). It has also been demonstrated that the extent to which the patient perceives the events as stressful, uncontrollable, or poorly handled also contributes to symptom severity (Horan et al., 2005; Renwick et al., 2009). Thus, individual differences in stress sensitivity may affect clinical presentation.

More recently, researchers have examined the impact of minor stressors, or “daily hassles” on patients with psychoses, with results indicating that severity of psychotic and mood symptoms are positively correlated with minor stressors (for a review, see Phillips et al., 2007). For example, findings from research using the experience sampling method to assess the immediate impact of stressful experiences indicate that patients with psychoses and their first-degree relatives are more reactive to daily stressors than are healthy controls, in that both groups report greater increases in negative affect and severity of psychotic symptoms in response to stressors (Habets et al., 2012; Myin-Germeys, Krabbendam, Delespaul, & van Os, 2003, 2004; Myin-Germeys, Marcelis, Krabbendam, Delespaul, & van Os, 2005; Myin-Germeys, van Os, Schwartz, Stone, & Delespaul., 2001).

Parallel to the findings from research with psychotic patients, cross-sectional data are inconsistent as to whether CHR participants experience more stressful life events than controls; however, CHR participants rate events as significantly more distressing than do controls (Phillips, Edwards, McMurray, & Francey, 2012). Similarly, although CHR individuals do not report a higher number of daily stressors, the evidence suggests that they perceive these occurrences as more stressful than do controls (Phillips et al., 2012; Tessner, Mittal, & Walker, 2011).

There is also support for the hypothesis that the association between stress and psychotic symptoms might be stronger in earlier phases of the illness. CHR participants endorsed higher levels of chronic stress than both controls and first episode psychosis patients, and chronic stress was a significant predictor of positive and depressive symptom severity only in the CHR group (Pruessner, Iyer, Faridi, Joober, & Malla, 2011). Similarly, a study using the experience sampling method found that CHR participants were more emotionally reactive to daily stressors than were healthy and patient groups, and positive symptoms were exacerbated by daily stress in both the CHR and psychosis groups (Palmier-Claus, Dunn, & Lewis, 2012).

Exposure to trauma in childhood, a more acute and severe form of psychosocial stress, has been linked with risk for subsequent psychosis in numerous investigations (for a review, see Varese et al., 2012). These traumatic experiences include physical and sexual abuse and exposure to violence and deprivation. For instance, a recent population study indicated that childhood sexual abuse increased the risk for psychotic symptomatology tenfold above the population risk (Bebbington et al., 2011). Several other population-based studies suggest that psychosis risk increases as a function of experiencing multiple traumas and/or types of trauma throughout childhood (Galletly, Van Hooff, & McFarlane, 2011; Janssen et al., 2004; Shevlin, Houston, Dorahy, & Adamson., 2008; Spauwen, Krabbendam, Lieb, Wittchen, & van Os, 2006), and a recent report concludes that this relation is due to a causal effect of trauma exposure rather than correlated family risk factors, as higher rates of childhood trauma are found in schizophrenia patients than in their unaffected siblings and healthy controls (Heins et al., 2011). In diagnosed schizophrenia patients, a history of exposure to child maltreatment is also linked with greater symptom severity and greater deficits in premorbid and cognitive functioning (Schenkel, Spaulding, DiLillo, & Silverstein, 2005).

Although limited in scope, the results of research on trauma in CHR samples is consistent with the above reports. Two reports conclude that the majority (>50%) of CHR individuals experienced a childhood trauma (Bechdolf et al., 2010; Thompson et al., 2009), and those who later converted to psychosis experienced more sexual trauma (Bechdolf et al., 2010). In a large sample of CHR participants from the NAPLS I project (Addington et al., 2007), a lower, but elevated, proportion reported some form of childhood physical or sexual abuse (Addington et al., 2013; Holtzman et al., 2011). These findings on childhood trauma in CHR samples converge with several reports on a link between childhood maltreatment and “psychotic-like” symptoms in youth. For example, the elicited speech samples of maltreated children were found to contain more illogical thinking than those of nonmaltreated children (Toth, Pickreign Stronach, Rogosch, Caplan, & Cicchetti, 2011), and the occurrence of psychotic symptoms within a school-based adolescent sample was associated with a higher rate of past exposure to maltreatment or bullying (Kelleher et al., 2008).

Taken together, the above results indicate that individuals at risk for psychosis may not experience a higher rate of events typically classified as stressful, but they are more sensitive to these events when they occur. In the realm of childhood trauma, however, it appears that exposure is significantly elevated and may contribute substantially to subsequent risk for psychosis.

The Biological Stress Response

The research on stress and psychosis raises intriguing questions about the biological processes mediating the relation. As noted, the HPA axis, one of the primary brain systems involved in the stress response, has been hypothesized to play a role. Within the last decade, a large body of literature has accumulated on HPA axis function in schizophrenia and other psychoses, and a review of the results support six general conclusions (Walker et al., 2008): (a) indices of HPA activity (cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone) are elevated in some patients with schizophrenia and other psychoses, especially in nonmedicated and first-episode patients; (b) antipsychotic medications typically reduce cortisol, with more pronounced reductions in drug responders; (c) both prescription and recreational drugs that exacerbate or induce psychotic symptoms also increase HPA activity; (d) illnesses (e.g., Cushing syndrome) associated with increased cortisol secretion are also linked with heightened risk for psychotic symptoms/syndromes; (e) receptors for glucocorticoids (i.e., cortisol in primates, corticosterone in rodents) appear to be downregulated in psychotic patients, suggesting reduced negative feedback on the HPA axis; and (f) reduced hippocampal volume, a correlate of hypercortisolemia, is among the most consistently reported brain abnormalities in psychotic patients.

Indices of the biological response to stress are of particular interest during the prodromal phase, given that stress is assumed to play a role in triggering symptom expression. To date, only a few published reports have addressed the relation of the HPA system, or its activity, with conversion to psychosis in a CHR or prodromal sample. In one study, pituitary volume was measured via magnetic resonance imaging in a CHR group (Garner et al., 2005). Participants who later developed psychosis had a significantly larger baseline pituitary volume compared with those who did not develop psychosis. The authors suggested that the larger pituitary volume may be indicative of heightened HPA activation. However, this research group conducted another study in which they administered the dexamethasone corticotrophin-releasing hormone (DEX/CRH) test to 12 CHR participants at baseline (Thompson et al., 2007); 3 of the 12 developed psychosis within 2 years. Given the small sample size, statistical analyses were not conducted, but the authors reported that participants who did not develop psychosis showed a trend toward higher plasma cortisol levels at the latter stages of the test when compared to the three participants who did develop psychosis.

In contrast, subsequent studies with larger samples have demonstrated that CHR individuals do manifest higher cortisol levels (Walker, Walder, & Reynolds, 2001; Weinstein, Diforio, Schiffman, Walker, & Bonsall, 1999). For example, a study comparing CHR youths (12–18 years) with (n = 14) and without (n = 56) subsequent transition to a psychotic disorder showed significantly higher cortisol levels in those who later converted to psychosis (Walker et al., 2010). As in previous studies of HPA activity in adolescence, an age-related increase in cortisol secretion was also observed, suggesting that the developmental period of peak risk for the onset of prodromal symptoms coincides with a period of elevated stress sensitivity. More recently, a report from the NAPLS consortium comparing 245 CHR and 141 healthy controls documented significantly higher baseline salivary cortisol in the CHR group (Walker et al., in press). Among those followed to 2 years, CHR participants who converted to a psychotic level of symptom severity had significantly higher baseline cortisol when compared to healthy controls and those CHR participants whose symptoms remitted.

Although there is substantial animal research demonstrating a link between glucocorticoids and dopamine (DA) in animal models (Barik et al., 2013), evidence of a relation between cortisol levels and brain DA in humans is only recently available, and it appears to be more pronounced in CHR and psychotic patients. A novel study measured stress-induced cortisol and DA release, using positron emission tomography to index the percentage change in receptor binding between conditions (challenging mental arithmetic task vs. control condition) in the limbic, associative, and sensorimotor striatum (Mizrahi et al., 2012). Compared to healthy controls, CHR and psychotic patients had a greater cortisol response to the stressor as well as a more pronounced DA response in the associative and sensorimotor striatum. Further, there was a significant correlation between the increases in cortisol and DA. As described below, the association between cortisol and DA activity has contributed to theoretical models about neurodevelopmental processes in psychosis.

Substance Use/Abuse

There is a well-established literature documenting the relation of illicit substance use with serious mental illness (Wisdom, Manuel, & Drake, 2011). Cannabis use has been the most consistently studied in recent years, and there is now a large body of literature showing it is associated with increased rates of relapse and poorer clinical course among individuals with schizophrenia; recent studies indicate that it increases risk for the initial onset of psychosis (Large, Sharma, Compton, Slade, & Nielssen, 2011; van Os et al., 2002). Moore et al. (2007) conducted a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies of cannabis use and later psychosis. After correcting for reverse causation (e.g., excluding those with baseline psychotic symptoms) and intoxication effects, their analysis yielded a pooled odds ratio of 1.41 (95% confidence interval = 1.20–1.65) for development of psychosis among those who had any use and 2.09 (95% confidence interval = 1.54–2.84) among frequent cannabis users. Consistent with this evidence, a prospective study of a CHR sample showed that cannabis abuse/dependence was associated with an increased likelihood of conversion to psychosis; 31% of those who converted to psychosis reported abuse/dependence versus only 3% of those who did not (Kristensen & Cadenhead, 2007).

More recently, there is evidence of an association between substance use and brain abnormalities. One study revealed that cannabis intake was inversely correlated with prefrontal gray matter volume (GMV) in both healthy controls and CHR participants, and the magnitude of the association did not differ for the two groups (Stone, Bhattacharyya, Barker, & McGuire, 2012). Another investigation focused on individuals at genetic high risk for psychosis found a significant relation of cannabis and alcohol use with ventricular enlargement as well as likelihood of developing psychosis (Welch et al., 2011). These effects may be especially problematic during the prodrome when, as described below, there is evidence of more pronounced brain volume decline.

Given the limitations of correlational studies for shedding light on causation, it is relevant to note that there are also experimental studies of the effects of administration of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the active agent in cannabis. THC has been shown to induce positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms of psychosis, including suspiciousness, conceptual disorganization, illusions, depersonalization, distorted sensory perceptions, and emotional withdrawal in healthy subjects (D’Souza et al., 2004). In subsequent reports, these researchers compared healthy nonusers and users of cannabis, and both groups responded to THC, in a dose-dependent manner, with brief psychotic-like signs, cognitive impairment, and increased cortisol (D’Souza et al., 2008; Ranganathan et al., 2009). Finally, one study examined the effects of THC on schizophrenia patients and healthy cannabis users; THC increased positive, negative, and general symptoms, cognitive deficits, and plasma prolactin and cortisol levels, with schizophrenia patients showing more THC-induced cognitive deficits than controls (D’Souza et al., 2005).

Brain Structure and Development

A large body of research has documented a range of brain abnormalities in schizophrenia and other psychoses. Notable among the regional differences are decreased volumes in the hippocampus (Adriano, Caltagirone, & Spalletta, 2012) and temporal regions (Siever & Davis, 2004), increased pituitary volume (Garner et al., 2005; Mondelli et al., 2008; Pariante et al., 2005; Pariante et al., 2004; Takahashi et al., 2009), and decreased frontal functioning (Davidson & Heinrichs, 2003; Hill, Schuepbach, Herbener, Keshavan, & Sweeney, 2004). Recent reviews of research on volumetric differences between psychotic patients and healthy controls conclude that there is a generalized reduction in cortical GMV in most regions, and this characterizes both first episode and chronic patients (Arnone et al., 2009; Levitt, Bobrow, Lucia, & Srinivasan, 2010), with some evidence of further GMV reduction over the course of illness in at least some patients (Hulshoff Pol & Kahn, 2008). In addition, studies of patients with psychosis onset during adolescence indicate that the GMV reductions, relative to same-age healthy controls, are more pronounced the earlier the onset of the illness (Douaud et al., 2009). Finally, comparisons of monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia indicate that volumetric reductions are more pronounced in the affected cotwin, especially for the perihippocampal region, indicating that the brain abnormalities in psychotic patients are partially independent of genetic factors (Borgwardt et al., 2010; van Haren et al., 2004).

More recently, volumetric abnormalities have been documented in CHR participants, with more significant abnormalities found in those who convert to psychosis (Fusar-Poli, Borgwardt, et al., 2011; Puri, 2010; Smieskova et al., 2010). For example, a meta-analysis of data from over 700 healthy control and 800 CHR participants revealed that the CHR group showed reduced GMV in multiple brain regions: the hippocampus, anterior cingulate, right superior temporal gyrus, left precuneus, left medial frontal gyrus, and right middle frontal gyrus (Fusar-Poli, Borgwardt, et al., 2011). Among the CHR group, those who later developed psychosis showed lower baseline GMV in the right inferior frontal gyrus and in the right superior temporal gyrus. Additionally, the hippocampus appears to be a brain region with marked volumetric reduction in patients with psychotic disorders as well as in those at elevated risk for psychosis (Witthaus et al., 2009). This is noteworthy, given evidence that the hippocampus plays a significant role in modulating HPA activity; it is one of the brain regions most sensitive to the adverse effects of persistent stress exposure (Walker et al., 2008).

Neurophysiology

Abnormalities in neurophysiological indices of brain function are among the most consistently reported biomarkers in schizophrenia and other psychoses. These abnormalities, which have also been observed in biological relatives of patients, fall in two general categories: (a) manifestations of failure to inhibit responses to redundant stimuli and (b) reduced deviance detection (i.e., a reduction in the typically observed facilitation of responses to infrequent, salient stimuli; Jeon & Polich, 2003; Turetsky et al., 2007; van der Stelt & Belger, 2007).

In the domain of inhibitory failure, the most consistently observed abnormalities in psychosis are decreases in prepulse inhibition (PPI), suppression of the P50 auditory-evoked potential, and suppression of antisaccades (AS), which are reflexive eye movements toward a stimulus (Cadenhead, 2002; Turetsky et al., 2007). PPI, sometimes referred to as “sensorimotor gating,” is the reduction in the eye-blink reflex response to a startling stimulus that results when it is preceded by a less intense and nonstartling “warning” stimulus, or pre-pulse (Cadenhead, 2002). A decrease in PPI reflects a failure to modulate the startle response as a function of information signaling an upcoming startling stimulus. P50 is a positive event-related potential (ERP) measured with EEG; it decreases in amplitude upon presentation of redundant or repetitious stimuli, indicating that the individual can “gate out” the redundant information. Finally, reflexive AS can be reduced with instructions to focus visual attention elsewhere, and the ability to do so is an index of the person’s capacity to inhibit the AS.

Measures of impaired deviance detection observed in psychosis include reductions in the P300 ERP and in “mismatch negativity” (MMN; Turetsky et al., 2007). The P300 is a large positive component of the poststimulus ERP waveform; it is more pronounced in response to novel stimuli, and it reflects the individual’s capacity to attend to and detect the stimulus, update working memory, and attribute salience to a deviant stimulus. A negative waveform, MMN is an ERP observed when a sequence of repetitive stimuli is periodically interrupted by a distinctly different stimulus. Thus, more pronounced MMN indicates greater capacity to detect differences among stimuli.

Neurophysiological studies of inhibitory processes in CHR subjects have generally yielded findings that parallel those reported for patients with psychosis. At least two studies have now shown that PPI is impaired in CHR subjects relative to healthy controls (Quednow et al., 2008; Ziermans, Schothorst, Magnee, van Engeland, & Kemner, 2011; Ziermans, Schothorst, Sprong et al., 2012). Similarly, several investigations have found that P50 suppression is reduced in CHR participants relative to healthy controls (Brockhaus-Dumke et al., 2008; Cadenhead, Light, Shafer, & Braff, 2005; Myles-Worsley, Ord, Blailes, Ngiralmau, & Freedman., 2004), although CHR subjects who did and did not convert to psychosis did not differ (Brockhaus-Dumke et al., 2008). One recent study of P50 suppression comparing CHR and healthy control participants revealed no significant difference (Ziermans, Schothorst, Schnack et al., 2012). In an investigation of AS, a measure of very basic inhibitory processes, Nieman et al. (2007) found that AS error rate (i.e., nonsuppression) was higher in the CHR group than in controls, and the schizophrenia patients had more AS errors than both the CHR and the control groups. There was a trend toward higher baseline AS error rates in the CHR patients who later converted to psychosis when compared to the CHR nonconverters.

Taken together, the above results provide neurophysiological evidence of inhibition deficits in CHR samples. There is also a growing body of literature indicating that neurophysiological measures of deviance detection are also impaired in CHR individuals. In a study of MMN to random novel auditory stimuli, MMN was reduced in both psychotic patients and in the CHR group (Atkinson, Michie, & Schall, 2012). Another study showed that reduced MMN was a predictor of conversion to psychosis in a CHR sample; these investigators found that, when compared with healthy controls and CHR nonconverters, CHR converters showed more pronounced MMN reductions across the frontocentral regions (Bodatsch et al., 2011). A similar investigation showed that CHR participants manifested a reduction of the MMN that was intermediate between healthy controls and schizophrenia patients, as well as a longer MMN latency, suggesting slowed processing (Brockhaus-Dumke et al., 2005).

Compared to other neurophysiological indices, there has been more empirical research on P300 in CHR samples. Not only has P300 been found to be abnormal in CHR participants, but there is also substantial evidence that it predicts conversion. Several studies have revealed that, when compared to controls, CHR samples, like patients diagnosed with psychotic disorders, manifest a reduction in the amplitude of P300 in response to auditory stimuli (Atkinson et al., 2012; Bramon et al., 2008; Frommann et al., 2008; van der Stelt, Lieberman, & Belger, 2005). Consistent with expectations, the reduction is less pronounced than that observed in psychotic patients (Ozgurdal et al., 2008). More recently, van Tricht and colleagues (2010) reported that CHR participants who convert to psychosis show smaller parietal P300 amplitudes at baseline when compared with CHR participants who do not convert. Further, the P300 reduction was associated with increased social anhedonia and withdrawal and poorer social functioning. In a follow-up study of the same sample, including a subgroup tested after a first psychotic episode, the course of auditory ERP was examined (van Tricht et al., 2011). CHR converters showed P300 amplitudes that were smaller than those of both healthy controls and CHR nonconverters before and after psychosis onset. Thus, P300 amplitudes were consistently reduced in CHR converters, suggesting P300 is a stable indicator of vulnerability.

There is interesting recent evidence of an association between P300 and structural brain abnormalities. Fusar-Poli and colleagues measured both P300 and GMV in individuals at CHR for psychosis (Fusar-Poli, Crossley, et al., 2011). As described above, when compared to controls, the CHR sample in this study showed reduced GMV, and the transition to psychosis was associated with more pronounced gray matter decline. Further, the CHR group showed reduced P300 amplitude, and smaller P300 amplitude was associated with smaller GMV in the frontal gyrus.

When combined with the findings on structural brain changes in CHR samples, especially those who convert to psychosis, the results of neurophysiological research suggest that the neurodevelopmental pathology subserving psychosis is reflected in both brain structure and function and that it predates the onset of the clinical syndrome. Interrupting this neuropathological process is the challenge that confronts future investigators.

Neurotransmitters

Hypotheses about DA dysregulation in psychosis have been prominent in the literature for decades (Howes & Kapur, 2009; Walker et al., 2008). The evidence supporting the role of DA comes from several lines of investigations, with numerous positron emission tomography studies showing that the magnitude of DA receptor blockade, particularly in the D2 receptor subtype, is associated with the clinical effectiveness of antipsychotics (Uchida et al., 2011). There is also robust evidence of a dysregulation of presynaptic DA activity in schizophrenia, leading to excessive DA release in the striatum, especially the areas projecting to the associative striatum where there is integration among cognitive and limbic cortical inputs (Miyake, Thompson, Skinbjerg, & Abi-Dargham, 2011).

Elevated striatal DA activity has recently been reported in CHR participants and appears to be linked with the emergence of psychotic symptoms. Heightened striatal DA activity, including increased DA synthesis, has been observed in CHR individuals prior to psychosis onset (Bauer, Praschak-Rieder, Kasper, & Willeit, 2012; Howes et al., 2009). Most recently, it has been found that transition to psychosis in CHR participants is associated with elevated DA function in the brainstem region (Allen et al., 2012).

Glutamate, the most prevalent excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, has also been implicated in psychotic disorders. Its effects on postsynaptic neurons are mediated by three families of receptors: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid, kainite, and N-methyl-d-aspartic acid. The psychotomimetic properties of agents (e.g., ketamine) that block acid receptors appear to be due to disruption of glutamatergic transmission and accumulation of extra cellular glutamate, a cause of oxidative stress and neurotoxicity (Coyle, Tsai, & Goff, 2002). A study of glutamate using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy revealed that both CHR and first episode psychotic patients showed higher levels of glutamate than did healthy controls (de la Fuente-Sandoval et al., 2011). Higher levels were found in the dorsal caudate but not in the cerebellum. These findings suggest that elevated glutamate is present in a DA-rich region implicated in psychosis pathophysiology and that it precedes the onset of the disorder. Along the same lines, measurement of the expression of proteins relevant to the glutamate system has revealed lower protein expression levels in schizophrenia, first episode of psychosis, genetic high risk, and CHR samples when compared with healthy controls (Correll, Hauser, Auther, & Cornblatt, 2010). Although the significance of this finding is not yet understood, it is additional evidence of a relation between glutamate abnormalities and the spectrum of psychotic syndromes.

Although the glutamate hypothesis is sometimes framed as a competitor to the DA hypothesis, the consensus among most researchers is that both the dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems play a role in the underlying etiology of psychotic illness and that their functioning is intimately linked (Coyle, 2006). For example, ketamine has been shown to increase amphetamine-induced DA release in healthy volunteers to levels normally seen in individuals with schizophrenia (Kegeles et al., 2000, 2002). The interconnectedness of these neuro-transmitter systems suggests that dysregulation in one can precipitate dysregulation in the other.

Summary of the CHR Research Findings

It has been clearly established that individuals at CHR for psychosis can be identified with current measures of prodromal syndromes. Moreover, these individuals manifest a range of behavioral deficits and biological abnormalities that parallel the findings on patients diagnosed with psychotic disorders. Included among these are cognitive deficits, greater stress sensitivity and HPA activity, and abnormalities in brain structure, function and neurotransmitters. Several of these indices have been shown to be associated with conversion to psychosis; thus, combining them with measures of clinical symptoms is expected to enhance positive predictive power. In addition, as we gain a better understanding of biomarkers and how they progress prior to illness onset, we will be able to generate more plausible models of the neural mechanisms underlying the emergence of psychotic disorders. In the following sections we explore some recent models.

Neurobiological Models of Psychosis Etiology

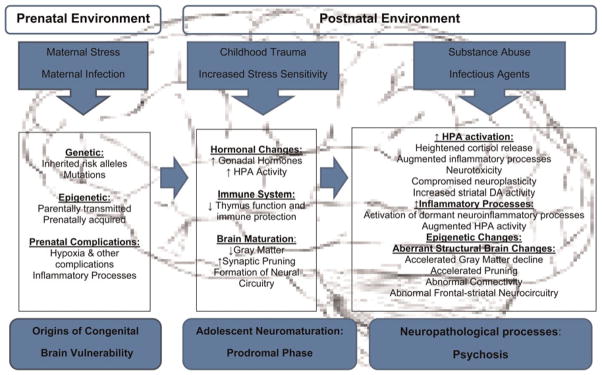

As noted, models of the etiology of psychosis have become more complex over the past few decades in conjunction with our increasing knowledge of the multifaceted interplay between biological and psychosocial factors in developmental psychopathology. Assumptions that played prominent roles in past etiologic models, particularly univariate assumptions about the inherited genetic origins of vulnerability, have been replaced by multivariate conceptualizations that encompass a range of factors and mechanisms affecting early brain development. These include genetic mutations, epigenetic processes and prenatal insults, such as exposure to infection. The elements that figure most prominently in contemporary models are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(Color online) The elements that figure most prominently in contemporary models.

In addition to the increasing complexity resulting from our more detailed knowledge of neurobiological mechanisms, contemporary models are also characterized by a greater recognition of developmental processes. Although the assumption that psychosis involves neurodevelopmental processes arose in the 1980s, more recent etiologic models have sharpened their focus on adolescent development and the prodromal period. A comprehensive review of etiologic models of psychosis is beyond the scope of this paper. The discussion below instead focuses on some recent models that attempt to account for the modal trajectory in which prodromal symptoms emerge in adolescence. Further, these models share the assumption that vulnerability typically originates in genetic and prenatal/perinatal factors that set the stage for subsequent psychosis.

As noted, stress has been implicated in the etiology of psychosis for many decades, but theorizing about the biological mechanisms mediating this effect has only recently entered into the discussion. Walker and colleagues (Walker & Diforio, 1997; Walker et al., 2008) proposed a “neural diathesis–stress model” that posits a congenital abnormality in striatal DA circuitry that is moderated in its expression by the activation of the HPA axis via both external stressors and endogenous neurodevelopmental processes. As described above, this model draws upon extensive evidence that measures of HPA activity are elevated in patients with schizophrenia and affective psychoses. It also links HPA activity with a posited downstream neural mechanism in psychosis, in that glucocorticoid release, via activation of the HPA axis, can augment DA activity in the striatum. In addition, it emphasizes the developmental parallels between the normal maturational increase in HPA activity that begins after the onset of puberty and the developmental course of the prodrome to psychosis (Trotman et al., in press).

Further, these authors note the pivotal role that both gonadal and adrenal hormones, including glucocorticoids, play in epigenetic processes. In a recent review of the literature on hormones and risk for psychosis, the authors provide an overview of research findings on the relation of steroid hormones with brain structure and function (Trotman et al., in press). Neurons in many human brain regions have both surface and intracellular receptors for hormones that mediate genomic and nongenomic processes, respectively. Thus, glucocorticoids, such as cortisol, have the potential, through genomic and nongenomic mechanisms, to alter the structure and function of the brain. Elevated cortisol secretion during the course of adolescence may trigger the expression of genes that confer vulnerability to aberrant neurodevelopment or may interfere with epigenetic processes in a manner that leads to aberrant brain development, such as exaggerated postpubertal decreases in GMV and neuronal connectivity. When coupled with increased DA activity, as suggested by findings reviewed above, this would be expected to result in abnormal function of neural circuits that govern perceptual and thought processes. Consistent with this view, there is extensive research documenting the adverse effects of elevated glucocorticoids on brain structure/function in animals (Kim & Haller, 2007) and more recent converging evidence of such a relation in humans. For example, a study using functional magnetic resonance imaging and EEG with administration of synthetic cortisol revealed rapid changes in the functioning and perfusion of the healthy human brain, presumably via nongenomic mechanisms (Strelzyk et al., 2012). At the structural level, studies of healthy and clinical samples have revealed an inverse association between cortisol levels and regional brain volumes. Cross-sectional studies have shown an inverse relation of cortisol with hippocampal volume in nonpsychiatric samples (Knoops, Gerritsen, van der Graaf, Mali, & Geerlings, 2010; Tessner, Walker, Dhruv, Hochman, & Hamann, 2007; Walker et al., 2008) and schizophrenia patients (Mondelli et al., 2010). Prospective research has revealed the same relations. In youths with anorexia nervosa, baseline cortisol levels were found to be correlated with GMV changes over the course of treatment (Mainz, Schulte-Ruther, Fink, Herpertz-Dahlmann, & Konrad, 2012). Increases in gray matter were associated with decreases in cortisol when measured simultaneously across time in anorexia patients (Castro-Fornieles et al., 2009). Similarly, in youths with trauma exposure, cortisol levels are negatively correlated with volume in the pre-frontal cortex and predict longitudinal declines in hippocampal volume (Carrion & Wong, 2012). Conversely, the reduction of cortisol levels in Cushing’s patients is associated with an increase in brain volume and a decrease in psychiatric symptoms (Hook et al., 2007). Thus, the adverse effects of heightened glucocorticoids on brain structure may be reversible.

Some recent perspectives on the neurodevelopmental processes in psychotic disorders have placed greater emphasis on the immune system (Kinney et al., 2010; Meyer, 2011). By way of background, inflammation entails secretion of inflammatory factors, including prostaglandins and cytokines. Cytokines are immunomodulating protein molecules, and they can be pro- and anti-inflammatory. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 1β, interleukin 6, and tumor necrosis factor α, contribute to febrile reactions and activation of phagocytotic cellsto combat the infection. Anti-inflammatory cytokines, for example, transforming growth factor β, and interleukin 10, counteract these effects and can be neurotrophic. Cytokines regulate immune cell differentiation as well as the recruitment and activation of lymphocytes, and some influence the induction of cell death and inhibit protein synthesis. Further, activation of the HPA axis and activation of immune processes are linked with similar neurochemical and neuroanatomical changes, and their effects are mutually mediated and synergistic (Zunszain, Anacker, Cattaneo, Carvalho, & Pariante., 2011). Thus, although glucocorticoids have anti-inflammatory effects at low/moderate levels, it has been demonstrated that exposure to persistent stress or the administration of glucocorticoids can increase the proinflammatory response to an immune challenge (Catena-Dell’Osso et al., 2011; Frank, Miguel, Watkins, & Maier, 2010). Conversely, activation of the immune response can augment HPA activity, via cytokines (Perez, Bottasso, & Savino, 2009). If persistent, both can be associated with neuroregressive and neurodegenerative processes (Zunszain et al., 2011).

In a recent neurodevelopmental model of psychosis, Meyer (2011) suggests how altered prenatal immune function might set the stage for vulnerability and moderate the course of subsequent development. He first reviews the evidence linking psychosis with prenatal exposure to a range of infections (e.g., viral and bacterial), which gave rise to maternal/fetal inflammatory responses (the “prenatal cytokine hypotheses”), as well as evidence showing increased proinflammatory responses in schizophrenia. He then offers an account of how prenatal exposure to immune challenge can contribute to early pre- and postnatal alterations in inflammatory response systems and disrupt subsequent development of neuronal systems. Under normal circumstances, homeostatic processes control inflammatory responses; in the brain, microglia and astrocytes play a pivotal role in modulating inflammatory processes via the production and regulation of cytokines. Further, cytokines’ neurotropic and neurodegenerative effects vary with developmental stage. For example, Meyer (2011) reviews evidence that exposure to prenatal infection and cytokines is linked with abnormal development of the DA system in animal models as well as structural brain abnormalities (e.g., ventricularenlargement and reduced cortical volume) in human adults. However, some effects of prenatal infection on brain development only become apparent in postpubescence, when previously dormant neuroinflammatory abnormalities are activated, possibly resulting in derailment of normal adolescent neuromaturational processes, such as myelination, synaptic pruning, and neuronal remodeling. Meyer emphasizes the role that physical and psychological stressors play in this process and suggests that stress and release of excitotoxic levels of glutamate by activated microglia may contribute to the exaggerated decrease in GMV and heightened glutamate levels observed in CHR samples, especially in the transition to psychosis.

Along similar lines, Kinney and colleagues (2010) propose a model that emphasizes how proinflammatory cytokines exacerbate risk for psychosis onset in adolescence/young adulthood due to developmental changes in immune function. In addition to the findings noted above, they draw on two lines of evidence: (a) alleles associated with increased risk for schizophrenia also affect the activity of proinflammatory cytokines, and (b) an excessive inflammatory response can produce an imbalance of glutamatergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission that leads to psychotic symptoms and a progressive loss of brain tissue that contributes to cognitive deficits. Like Meyer (2011), these authors assume that prenatal factors can confer a latent vulnerability in the immune system that is relatively dormant until puberty. In particular, they note that prenatal exposure to maternal stress, nutritional deficiency, and infection can lead to thymus gland dysfunction in offspring, which is subsequently heightened during adolescence when the thymus gland normally regresses in volume. The thymus gland is important to the immune system because it produces T cells (T lymphocytes), which play a central role in adaptive immune function. With atrophy of the thymus in adolescence, latent immune vulnerability is manifested, and individuals become more susceptible to infectious and/or immune diseases that can contribute to the onset of psychosis. Further, Kinney and colleagues (2010) emphasize the deleterious effects of stress and glucocorticoids on immune function as well as the evidence that neuroinflammation and the proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor α) adversely affect neurogenesis, synapse formation, neuronal connectivity, and the survival of neurons.

Related to the above model, a key feature of 22q11 deletion syndrome, a chromosomal disorder that is associated with a 20- to 30-fold increase in risk for psychosis, is early loss of the thymus resulting in reduced T cells, immune deficiency, and reduced resistance to infection (Bassett & Chow, 2008; Shapiro et al., 2011). It is noteworthy that this genetic cause of thymus dysfunction in humans is also linked with a dramatic increase in risk for psychosis.

Some other neurodevelopmental models have focused greater attention on the brain circuitry or connectivity changes associated with psychosis. For example, it has been proposed that genetic and other factors can lead to early developmental disruptions in intra- and interregional connectivity and thereby give rise to a psychosis vulnerability that is expressed in late adolescence/early adulthood (Karlsgodt et al., 2008; Uhlhaas & Singer, 2011). These models draw on research findings that psychotic disorders are associated with postmortem evidence of reductions in synapse density and dendritic complexity as well as findings from in vivo magnetic resonance imaging studies showing white matter changes indicative of deficient connections among cortical regions. The functional expression of abnormal connectivity, in the form of prodromal symptoms, may arise in adolescence because preexisting abnormalities interact with the normal adolescent process of synaptic pruning and/or because the pruning process itself is abnormal. At the level of neurotransmitters, one recent model emphasizes the importance of circuits in the pre-frontal cortex that involve glutamatergic and GABA-ergic transmission and are characterized by heightened sensitivity to environmental perturbation during adolescent development (Hoftman & Lewis, 2011). Again, these connectivity models incorporate stress systems as one of the mechanisms contributing to circuitry abnormalities.

Future Directions in CHR Research

The above models suggest some promising avenues for future research on the prodrome to psychosis. But before turning to a discussion of future directions, several key points should be noted. First, although models of the neurodevelopment of psychosis vary in the risk factors, levels of analysis, and processes they emphasize, it is evident that there is convergence among them on certain elements. Among these are genetic and prenatal factors that give rise to vulnerability, endogenous neurodevelopmental processes that are associated with adolescence, biological systems mediating the response to stress, and neuroplasticity. Second, they assume both continuities and discontinuities in the developmental trajectories that lead to psychosis. Although there are often abnormalities in premorbid childhood behavior, the prodromal phase typically involves a significant departure from previous levels of behavioral adaptation and entails a derailment of normal adolescent/young adult development (Walker, 1994). Third, it has become evident that the emergence of psychosis involves a confluence of dynamic factors and that these vary among affected individuals. Thus, although the final common pathway may entail a disruption in striatal–frontal brain circuits in which DA, glutamate, and GABA are the biochemical messengers, this disruption is the endpoint of multiple etiologic pathways. With these caveats in mind, it is imperative that future research (a) takes a multilevel, developmental approach that encompasses environmental, behavioral and biological indices, and (b) assumes that the relative influence of each will vary among individuals.

Characterizing congenital vulnerability factors

Concerning congenital brain vulnerability, it is now clear that the genome and measures of prenatal complications and early infectious exposures will be important basic levels of analysis for future research on the psychosis prodrome (see Figure 1, left panel). The rapidly accumulating data on mutations, both inherited and de novo, suggest that aberrations in the DNA that codes for proteins involved in neurodevelopmental processes is one source of vulnerability for some CHR individuals. Thus, indexing the mutational load will be an important point of departure for longitudinal study of neurodevelopmental pathways. Differences among CHR individuals in the nature and/or magnitude of this load may determine the subsequent course with respect to developmental triggers and processes. For example, those with higher levels of copy number variants may be characterized by more pronounced cognitive deficits and greater or lesser sensitivity to environmental triggers, such as substance use and stress.

In addition, characterizing individual genotypes, especially with respect to genes that are known to be involved in neuronal plasticity and stress sensitivity, will be an important component of future CHR research. As a case in point, certain polymorphisms of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor and catechol-O-methyltransferase genes have been shown to influence HPA activity (Alexander et al., 2010; Shalev et al., 2009; Walder et al., 2010). Thus, there may be a complement of genes that determine the nature of changes in biological stress sensitivity during adolescence, and it is possible that they are linked with a particularly stress-sensitive subtype of psychosis.

Similarly, early prenatal or postnatal inflammatory processes may confer vulnerability. As noted above, prenatal factors, such as maternal infection, can result in abnormalities in inflammatory processes that set the stage for greater sensitivity to later exposures or to biological changes that occur following the onset of puberty. To date, we are aware of no research on immune function in CHR samples, so this is a critical area for investigation. Measures of immune function in CHR youths will provide an indirect index of such early exposures and determine the extent of the individual’s sensitivity to changing neuroimflammatory processes during adolescence.

Tracking biobehavioral processes

The prodrome, as defined by the onset of attenuated positive symptoms and functional decline, is usually observed by late adolescence (Figure 1, middle panel). It is therefore imperative that potentially relevant neuromaturational processes be repeatedly measured at multiple levels (e.g., cognitive, hormonal, neuroanatomical), in conjunction with symptoms and behavioral changes through adolescence and into early adulthood.

Because neuronal receptors for hormones can trigger epigenetic processes that alter brain structure and function, adrenal and gonadal hormone changes will be an important domain to target. Neuroendocrinologists have not yet identified all of the components and causal pathways involved in pubertal development, but it is evident that changes in gonadal hormones are linked with changes in brain structure that occur following puberty (Peper et al., 2011). Changes in adrenal hormones, such as cortisol, appear to also affect brain development. By tracking the relative increases in gonadal and adrenal hormones, it will be possible to map them onto changes in brain structure and the progression of prodromal symptoms.

At the genetic level, high priority should be given to studies of epigenetic processes that might be triggered by hormonal changes or inflammatory processes during the course of adolescence/young adulthood in CHR youths (Figure 1, right panel). Changes in epigenetic profiles that distinguish CHR and healthy youths may hold critical clues to etiological mechanisms. The study of epigenetic processes is now possible due to new technologies that allow researchers to examine between and within-individual differences in gene expression, such as those reflected in DNA methylation profiles (Hunter, 2012). Further, advances in proteomics have made it possible to examine variations in protein expression that may be relevant to brain structure/function. Examination of the longitudinal relation between hormone changes and patterns of gene and protein expression will enable investigators to disentangle interactive causal processes. In particular, given the evidence of heightened cortisol secretion in the psychosis prodrome, epigenetic processes triggered by glucocorticoids are of interest.

At the level of brain structure, the changes that have been documented in conjunction with conversion to psychosis, such as decreased GMV and white matter indicators of connectivity, should be a major focus in future CHR research. We need to better understand how these changes are related with indicators of vulnerability. The same can be said of hormonal and epigenetic changes, which are especially important because they may elucidate plausible modes of preventive intervention.

Finally, environmental exposures should be tracked to determine how these influence the progression of the prodrome both biologically and phenomenologically. Some of the key factors are listed in the upper portion of Figure 1. The psychosocial environment, and its relation with the biological processes described above, will be an important domain. Given the evidence that psychosis is associated with early trauma exposure and heightened stress sensitivity, the measurement of past and current exposure to trauma and psychosocial stress may prove to be highly informative. This will allow investigators to examine in greater detail the interplay between the psychosocial environment and the genesis of the neurobiological processes that give rise to the first psychotic episode. Similarly, biological exposures, especially substance use, should be documented to examine covariation with biobehavioral indicators of prodrome progression. The findings will also be pivotal for future research on preventive intervention.

New perspective on conceptualizing prevention

The apparent multivariate and dynamic nature of psychosis neurodevelopment has given rise to a new perspective on preventive intervention. Past scientific views of psychotic disorders assumed firm diagnostic boundaries and diagnostically specific, inherited-risk genotypes. In the present era, the dominant view is of a spectrum of psychotic disorders that involve nonspecific prenatal and genetic vulnerability factors as well as dynamic neuropathological processes that are moderated by the environment and neuromaturational processes. Although this complex new view may defy our preference for conceptual simplicity, it does suggest that leverage for preventive intervention may be much greater than previously assumed.

For example, it has been demonstrated, in both animal and clinical research, that modulation of hormones can alter brain structure across the human life span (Furrow et al., 2011; Hunter, 2012; Trotman et al., in press). Similarly, agents that alter inflammatory responses can change the trajectory of brain development and degenerative processes (Khansari & Halliwell, 2009). Finally, and perhaps most fascinating, psychosocial interventions can modify both hormonal and immune processes and may offer greater leverage for prevention than we had imagined (Antoni et al., 2009). These new avenues for potential prevention can also serve as informative probes in understanding the neural mechanisms subserving the emergence of psychosis.

Although research on the prevention of psychosis in CHR samples has just recently been undertaken, there are several new leads. To date, efforts to prevent the onset of psychosis in CHR groups with antipsychotic medication have met with limited success; although antipsychotics appear to reduce prodromal symptoms’ severity and delay the onset of psychosis, they have not yet been shown to ultimately result in a significant decrease in conversion rates (Addington & Heinssen, 2012). More promising are some studies indicating that cognitive–behavioral and supportive therapy reduce the severity of prodromal syndromes and the likelihood of conversion to psychosis over a 12-month period (Addington & Heinssen, 2012). Longer term (e.g., 3-year) follow-ups have not yet revealed a significant sustained effect, although they are still underway. A very promising recent report from a European research group indicates that omega-3 fatty acid supplement can significantly reduce psychosis risk at 12-month follow-up in CHR samples (Amminger et al., 2010). A double-blind study attempting to replicate these findings is currently being conducted in the United States by the NAPLS group. Although the results of this and other attempts at replication are needed before firm conclusions can be drawn, it is of interest to note that omega-3 is known to reduce HPA activity and inflammation, thus affecting some of the pathways that have been implicated in psychosis (Michaeli, Berger, Revelly, Tappy, & Chiolero, 2007; Yehuda, Rabinovitz, & Mostofsky, 2005).

In summary, dramatic advances in genetics and neuroscience have had an impact on virtually all fields of biomedical research and behavioral science. Like many other areas of investigation in human development, researchers in the field of psychopathology are aware that our past assumptions were overly simplistic and, in some cases, erroneous. However, in many respects, there is reason for greater optimism about preventive intervention for psychosis than ever before. The neurobiological systems that are involved in the pathological process(es) that lead to psychosis appear to be much more malleable than we had imagined.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by Grant U01MHMH081988 from the National Institute of Mental Health (to E.F.W.).

References

- Addington AM, Rapoport JL. Annual research review: Impact of advances in genetics in understanding developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2012;53:510–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Cornblatt B, McGlashan T, Perkins D, et al. North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study: A collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:665–672. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Heinssen R. Prediction and prevention of psychosis in youth at clinical high risk. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:269–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J, Stowkowy J, Cadenhead KS, Cornblatt BA, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, et al. Early traumatic experiences in those at clinical high risk for psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2013;7:300–330. doi: 10.1111/eip.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriano F, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. Hippocampal volume reduction in first-episode and chronic schizophrenia: A review and meta-analysis. Neuroscientist. 2012;18:180–200. doi: 10.1177/1073858410395147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander N, Osinsky R, Schmitz A, Mueller E, Kuepper Y, Hennig J. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism affects HPA-axis reactivity to acute stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:949–953. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen P, Luigjes J, Howes OD, Egerton A, Hirao K, Valli I, et al. Transition to psychosis associated with prefrontal and subcortical dysfunction in ultra high-risk individuals. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38:1268–1276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Arlington, VA: Author; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Amminger GP, Schafer MR, Papageorgiou K, Klier CM, Cotton SM, Harrigan SM, et al. Long-chain omega–3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:146–154. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Lechner S, Diaz A, Vargas S, Holley H, Phillips K, et al. Cognitive behavioral stress management effects on psychosocial and physiological adaptation in women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23:580–591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnone D, Cavanagh J, Gerber D, Lawrie SM, Ebmeier KP, McIntosh AM. Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: Meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195:194–201. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR. Childhood-onset schizotypal disorder: A follow-up study and comparison with childhood-onset schizophrenia. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2005;15:395–402. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RJ, Michie PT, Schall U. Duration mismatch negativity and P3a in first-episode psychosis and individuals at ultra-high risk of psychosis. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barik J, Marti F, Morel C, Fernandez SP, Lanteri C, Godeheu G, et al. Chronic stress triggers social aversion via glucocorticoid receptor in dopaminoceptive neurons. Science. 2013;339:332–335. doi: 10.1126/science.1226767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett AS, Chow EW. Schizophrenia and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2008;10:148–157. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0026-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Praschak-Rieder N, Kasper S, Willeit M. Is dopamine neurotransmission altered in prodromal schizophrenia? A review of the evidence. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2012;18:1568–1579. doi: 10.2174/138161212799958611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington P, Jonas S, Kuipers E, King M, Cooper C, Brugha T, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: Data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;199:29–37. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechdolf A, Thompson A, Nelson B, Cotton S, Simmons MB, Amminger GP, et al. Experience of trauma and conversion to psychosis in an ultra-high-risk (prodromal) group. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;121:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodatsch M, Ruhrmann S, Wagner M, Muller R, Schultze-Lutter F, Frommann I, et al. Prediction of psychosis by mismatch negativity. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:959–966. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Cognitive impairment in affective psychoses: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:112–125. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgwardt SJ, Picchioni MM, Ettinger U, Toulopoulou T, Murray R, McGuire PK. Regional gray matter volume in monozygotic twins concordant and discordant for schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramen JE, Hranilovich JA, Dahl RE, Forbes EE, Chen J, Toga AW, et al. Puberty influences medial temporal lobe and cortical gray matter maturation differently in boys than girls matched for sexual maturity. Cerebral Cortex. 2011;21:636–646. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramon E, Shaikh M, Broome M, Lappin J, Berge D, Day F, et al. Abnormal P300 in people with high risk of developing psychosis. NeuroImage. 2008;41:553–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus-Dumke A, Schultze-Lutter F, Mueller R, Tendolkar I, Bechdolf A, Pukrop R, et al. Sensory gating in schizophrenia: P50 and N100 gating in antipsychotic-free subjects at risk, first-episode, and chronic patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus-Dumke A, Tendolkar I, Pukrop R, Schultze-Lutter F, Klosterkotter J, Ruhrmann S. Impaired mismatch negativity generation in prodromal subjects and patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;73:297–310. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenhead KS. Vulnerability markers in the schizophrenia spectrum: Implications for phenomenology, genetics, and the identification of the schizophrenia prodrome. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2002;25:837–53. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(02)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadenhead KS, Light GA, Shafer KM, Braff DL. P50 suppression in individuals at risk for schizophrenia: The convergence of clinical, familial, and vulnerability marker risk assessment. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:1504–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, Woods SW, Addington J, Walker E, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: A multisite longitudinal study in North America. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion VG, Wong SS. Can traumatic stress alter the brain? Understanding the implications of early trauma on brain development and learning. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:S23–S28. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Fornieles J, Bargallo N, Lazaro L, Andres S, Falcon C, Plana MT, et al. A cross-sectional and follow-up voxel-based morphometric MRI study in adolescent anorexia nervosa. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catena-Dell’Osso M, Bellantuono C, Consoli G, Baroni S, Rotella F, Marazziti D. Inflammatory and neurodegenerative pathways in depression: A new avenue for antidepressant development? Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2011;18:245–255. doi: 10.2174/092986711794088353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmandari E, Kino T, Souvatzoglou E, Chrousos GP. Pediatric stress: Hormonal mediators and human development. Hormone Research. 2003;59:161–179. doi: 10.1159/000069325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, Cornblatt BA. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: A review of the current evidence and future directions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2010;51:390–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Tsai G, Goff DC. Ionotropic glutamate receptors as therapeutic targets in schizophrenia. Current Drug Targets: CNS and Neurological Disorders. 2002;1:183–189. doi: 10.2174/1568007024606212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson L, Heinrichs R. Quantification of frontal and temporal lobe brain-imaging findings in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research. 2003;122:69–87. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(02)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]