Abstract

Victims of drug- or alcohol-facilitated/incapacitated rape (DAFR/IR) are substantially less likely to seek medical, rape crisis, or police services compared with victims of forcible rape (FR); however, reasons for these disparities are poorly understood. The current study examined explanatory mechanisms in the pathway from rape type (FR vs. DAFR/IR) to disparities in post-rape service seeking (medical, rape crisis, criminal justice). Participants were 445 adult women from a nationally representative household probability sample who had experienced FR, DAFR/IR, or both since age 14. Personal characteristics (age, race, income, prior rape history), rape characteristics (fear, injury, loss of consciousness), and post-rape acknowledgment, medical concerns, and service seeking were collected. An indirect effects model using bootstrapped standard errors was estimated to examine pathways from rape type to service seeking. DAFR/IR-only victims were less likely to seek services compared with FR victims despite similar post-rape medical concerns. FR victims were more likely to report fear during the rape and a prior rape history, and to acknowledge the incident as rape; each of these characteristics was positively associated with service seeking. However, only prior rape history and acknowledgment served as indirect paths to service seeking; acknowledgment was the strongest predictor of service seeking. Diminished acknowledgment of the incident as rape may be especially important to explaining why DAFR/IR victims are less likely than FR victims to seek services. Public service campaigns designed to increase awareness of rape definitions, particularly around DAFR/IR, are important to reducing disparities in rape-related service seeking.

Keywords: sexual assault, alcohol and drugs, support seeking

Introduction

An estimated 65% of rapes in the United States between 2006 and 2010 went unreported to police, making rape the most underreported violent crime in the country (Langton, Berzofsky, Krebs, & Smiley-McDonald, 2012). Similarly, only one in five rape victims seek rape-related medical services (Zinzow, Resnick, Barr, Danielson, & Kilpatrick, 2012). Rape victims may fail to seek post-assault services for several reasons including fear of reprisal (Kilpatrick, Resnick, Ruggiero, Conoscenti, & McCauley, 2007; Langton et al., 2012; Thompson, Sitterle, Clay, & Kingree, 2007; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2011), not wanting the assailant to go to jail (Jones, Alexander, Wynn, Rossman, & Dunnuck, 2009), not wanting family or others to know about the rape (Kilpatrick et al., 2007; Thompson et al., 2007; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2011; Zinzow & Thompson, 2011), shame or embarrassment (Logan, Evans, Stevenson, & Jordan, 2005; Thompson et al., 2007), lack of access to or knowledge regarding available medical and mental health services (Logan et al., 2005), failure to acknowledge the incident as a rape (Cohn, Zinzow, Resnick, & Kilpatrick, 2013; Kilpatrick et al., 2007), and fear of not being believed, being blamed, or otherwise treated poorly by police, lawyers, or medical providers (Campbell, Wasco, Ahrens, Sefl, & Barnes, 2001; Cohn et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2009; Sable, Danis, Mauzy, & Gallagher, 2006; Thompson et al., 2007).

Recently, researchers have focused on understanding the role of drug and alcohol use as a potentially important barrier to service seeking among rape victims. Approximately half of all rapes involve alcohol use by the victim, perpetrator, or both (Abbey, Zawacki, Buck, Clinton, & McAuslan, 2004). An estimated 5.6 million women in the United States will have experienced a drug- or alcohol-facilitated/incapacitated rape (DAFR/IR) at some time in their lives (Kilpatrick et al., 2007). DAFR/IR has been defined as rape in which the victim voluntarily ingested alcohol or drugs (IR) or was administered alcohol or drugs by another person (DAFR) that results in impairment that interferes with the ability to consent or resist (Kilpatrick et al., 2007). A national study found that incidents involving DAFR/IR accounted for 22% of all lifetime rape incidents (whether or not forcible elements were also present), and approximately 50% of these incidents involved only DAFR/IR without any elements of force (Kilpatrick et al., 2007). However, in cross-sectional studies, DAFR/IR victims were less likely than forcible rape (FR) victims to report the incident to police (Fisher, Daigle, Cullen, & Turner, 2003; Kilpatrick et al., 2007) or to seek post-rape medical care (Resnick et al., 2000; Zinzow et al., 2012). A recent report indicated that rape victims who had lost consciousness as a result of alcohol or drugs were less likely to continue with police investigation (Kelley & Campbell, 2013).

There are multiple potential factors related to reduced service seeking among DAFR/IR victims. Rape script theories suggest that incidents matching stereotypic rape scenarios are most likely to be acknowledged as rape by victims (Littleton, Axsom, Breitkopf, & Berenson, 2006), and acknowledgment is an important factor in determining service use and reporting behavior (Cohn et al., 2013). Supporting this theory, cross-sectional studies have linked the following stereotypic rape characteristics to increased likelihood of service seeking and police reporting: use of force, stranger perpetrator, physical injury, and peri-traumatic fear (Ullman & Filipas, 2001; Zinzow et al., 2012). Although one cross-sectional study found that college students included substance use by the victim or perpetrator in the majority of their rape scripts (Turchik, Probst, Irvin, Chau, & Gidycz, 2009), several cross-sectional studies have found that men and women were less likely to label incidents as rape if substance use by the victim, the perpetrator, or both was involved (Kahn, Jackson, Kully, Badger, & Halvorsen, 2003; Norris & Cubbins, 1992; Richardson & Campbell, 1982),

As a result of acute intoxication or impairment, including loss of consciousness, DAFR/IR victims may experience less fear of death or injury during the rape relative to FR victims. Although there have been no studies to explicitly examine whether DAFR/IR victims are less likely to experience peri-traumatic fear, there are indications from studies of other types of trauma (e.g., a ballroom fire) that alcohol consumption and intoxication immediately preceding the trauma decrease the odds of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a fear-based disorder, over a 7- to 9-month follow-up (Maes, Delmeire, Mylle, & Altamura, 2001). Furthermore, in cross-sectional studies, women without injury are less likely to label the incident as a rape (Cohn et al., 2013; Fisher et al., 2003; Kahn et al., 2003; Littleton et al., 2006). Potentially lower levels of fear and injury may lead DAFR/IR victims to have less acknowledgment of the incident as a rape, thereby reducing their recognition of service eligibility or needs.

Another factor that could account for disparities in service seeking between DAFR/IR and FR victims is that DAFR/IR victims may have less detailed recall of the rape due to their level of substance-induced impairment during the rape. Women with diminished recall or those who passed out during some or all of the rape may be less likely to seek post-assault services because they are concerned about negative judgments about their substance use (Sims, Noel, & Maisto, 2007), concerns about reporting illicit drug use if present, or concerns about being turned away from services because they are unable to provide a complete account. Some victims may be unsure about what happened and whether they need services. Substance-related rape has been associated with poorer criminal justice outcomes and differential processing (Kelley & Campbell, 2013). Thus, fear of negative evaluation or treatment may be valid in some cases.

Finally, it may be important to consider whether having a prior history of sexual assault might influence service-seeking behavior. Specifically, women with a prior history of rape have been shown to have elevated levels of self-blame and shame regarding their experiences (Filipas & Ullman, 2006) and thus could be less likely to seek services due to greater concern about negative reactions from others. Conversely, in cross-sectional studies, revictimized women have been shown to have higher levels of psychopathology (Filipas & Ullman, 2006; Walsh et al., 2012) and may be more likely to seek services due to their greater mental health needs (Filipas & Ullman, 2006). Prior studies have not explicitly examined prior history of assault as a factor in all types of service-seeking behavior.

The current study extended existing research by examining predictors of rape-related service-seeking behavior among a large nationally representative sample of women. Several factors including demographic characteristics, assault-related factors, acknowledgment of the incident as rape, and post-rape medical concerns (HIV, Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD), or pregnancy concerns) were examined as potential mechanisms accounting for disparities in service seeking (police reporting, rape crisis advocacy, post-rape medical care) observed as a function of rape type (FR vs. DAFR/ IR-only). In the few studies that have examined DAFR/IR incidents that do not involve force elements, victims of DAFR/IR have been less likely to seek services (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2011; Zinzow et al., 2012). Therefore, we hypothesize that victims of DAFR/IR-only will be significantly less likely than FR victims to seek services. The current report goes beyond previous studies by evaluating service seeking more broadly, comparing rape and demographic characteristics among rapes that are exclusively DAFR/IR versus rapes that involve any force, and examining potential explanatory mechanisms for the hypothesized inverse association between DAFR/IR-only and service seeking. Greater understanding of potential mediators of reduced agency engagement and service seeking among those experiencing DAFR/ IR-only may highlight approaches to reduce disparities in receipt of health care, advocacy services, and criminal justice system involvement.

Method

Sample and Procedures

A household probability sample of 3,001 adult women participated in the 2006 National Women's Study Replication (NWS-R) phone survey, a study of the prevalence and characteristics of rape. Random digit dial methods were used to contact potential participants. Once household eligibility was determined, informed consent and the telephone interview were administered. Of those eligible for participation (n = 3,817), 12.9% (n = 492) refused to participate and 8.5% (n = 324) did not complete the interview. Thus, the cooperation and interview completion rate among eligible women was 78.6%. Younger women were oversampled to assist in comparisons with college women; however, because the majority of women in the general population sample were between the ages of 18 and 34 years, weights were created to approximate the 2005 U.S. Census estimates. Our analyses for this study were restricted to the 445 women (73.3% White, 7.8% college students, M age = 33.2 years, SD = 10.3 years) in this nationally representative household probability sample who had experienced FR, DAFR/IR, or both since age 14. Additional detailed information regarding the sample has been published elsewhere (Kilpatrick et al., 2007). Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographic information

Women were asked to report their age, race, and estimated personal yearly income.

Rape experiences

Consistent with the National Women's Study (Acierno et al., 2001), behaviorally specific questions assessed women's most recent or only rape that occurred at age 14 or above. Specific screening questions are reported elsewhere (Kilpatrick et al., 2007). Rape was defined as unwanted penetration of the victim's vagina, mouth, or rectum. Cases were defined as FR if the incident involved force, threat of force, or injury. Cases were defined as DAFR/IR if the victim was intoxicated and incapacitated (passed out due to substance use or too drunk or high to know what they were doing/control their own behavior) via voluntary or involuntary consumption of drugs and/or alcohol. Cases that involved both FR and DAFR/IR (64 cases, representing 17% of all FR incidents and approximately half of all DAFR/IR incidents) were coded together as FR because preliminary analyses indicated that FR and FR + DAFR/IR women evidenced similar associations with important variables of interest including acknowledgment of the incident as rape (75% vs. 62%), having a prior rape history (51% vs. 56%), and service seeking (33% vs. 46%). In all analyses, FR victims were coded “1” and DAFR/IR-only victims were coded “0.” Several rape incident characteristics were assessed for the most recent/only incident, including victim age, relationship to the perpetrator, peri-traumatic fear (fear of death/injury), whether the victim remembered the event well, whether the victim acknowledged the incident as a rape, and level of incapacitation (i.e., passed out, incapacitated but not passed out, not incapacitated). Prior lifetime rape history was also assessed using the same instrument; participants were coded as having a prior rape if they reported both a most recent rape incident and a prior rape incident. All variables except for victim age were coded as dichotomous variables.

Post-rape concerns

Participants used a four-point scale to rate the following post-incident concerns: (a) “getting a sexually transmitted disease, other than AIDS or HIV,” (b) “getting AIDS or HIV,” and (c) “getting pregnant as a result of the assault.” Responses were dichotomized as 0 (not really or a little concerned) and 1 (somewhat and extremely concerned).

Service seeking

Three items assessed whether participants: (a) reported the incident to the police, (b) sought help or advice from an agency that provides assistance to victims of crime, or (c) received any medical attention after the incident. Because there was substantial overlap among these three dichotomous variables (e.g., 75% and 60% of those who reported to the police also sought medical or crisis services, respectively), a single variable reflecting any service seeking was created (1= yes to any service seeking and 0 = no to all service seeking).

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate analyses were conducted in SPSS version 19.0; chi-square analyses were used to examine categorical demographic and incident characteristics, and analysis of variance was used to examine continuous demographic characteristics (age). Logistic regression analyses were used to examine differences between FR and DAFR/IR-only cases on service-seeking behavior. Multivariate analyses were conducted in Mplus version 6.1 using bootstrapped standard errors to estimate the indirect effects; models were adjusted for age and income and weighted to account for oversampling of younger women. We estimated three models: Model A reflected the direct effect from rape type to service seeking; Model B reflected a simultaneous indirect effects model wherein the significant rape characteristics in bivariate analyses were included as potential explanatory variables in the path from rape type to service seeking; Model C reflected a trimmed model wherein non-significant paths were excluded according to Kline's (2005) recommendations. Explanatory variables were allowed to correlate in Models B and C. Model fit statistics, R2, and both unstandardized and standardized estimates were provided. Model fit statistics were evaluated according to Hu and Bentler's (1999) recommendations that the comparative fit index (CFI) be greater than .95, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) be less than or equal to .06. To compare the magnitude of significant indirect effects, the product of coefficients method was used to calculate the indirect effects and the coefficients were directly compared.

Results

One third (32%) of victims sought any services in the total sample. Demographic and most recent incident characteristics and service seeking of those with FR and DAFR/IR-only are presented in Table 1. Compared with women in the DAFR/IR-only group, women in the FR group were older (44.3, SD = 15.7, vs. 32.9, SD = 9.7, p < .001), reported more fear of injury or death during the rape, had greater memory for the rape, were more likely to have been raped by a romantic partner, have acknowledged the incident as rape, have had a history of prior rape, and have sought medical, crisis, and police services.

Table 1.

Demographics, Rape Characteristics, and Post-Rape Concerns Among Victims With FR Versus DAFR/IR-Only and Among Those Who Did and Did Not Seek Rape-Related Services.

| FR (n = 380) | DAFR/IR-Only (n = 65) | χ2, F | Sought Services (n = l44) | Did Not Seek Services (n = 30l) | χ2, F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 4.58 | 8.45* | ||||

| >60K | 26% | 39% | 20% | 32% | ||

| 20K-60K | 46% | 36% | 45% | 44% | ||

| <20K | 28% | 25% | 35% | 24% | ||

| Race | 3.59 | 6.90 | ||||

| White | 76% | 78% | 72% | 79% | ||

| Black | 16% | 9% | 18% | 14% | ||

| Hispanic | 4% | 6% | 4% | 5% | ||

| Other | 3% | 6% | 6% | 2% | ||

| Fear | 62% | 2% | 76.22*** | 72% | 43% | 3l.60*** |

| Memory | 77% | 18% | 87.55*** | 72% | 67% | 1.19 |

| Any DAFR/IR | 17% | 100% | 28% | 30% | 0.21 | |

| Perpetrator | 27.95*** | 9.04 | ||||

| Stranger | 13% | 16% | 19% | 10% | ||

| Not known well | 15% | 30%** | 14% | 19% | ||

| Partner | 33% | 11%*** | 31% | 30% | ||

| Relative | 9% | 5% | 8% | 9% | ||

| Friend | 16% | 33%** | 16% | 21% | ||

| Acquaintance | 14% | 6% | 13% | 13% | ||

| Acknowledged as rape | 73% | 24% | 54.76*** | 85% | 56% | 35.43*** |

| Multiple rape history | 52% | 30% | 11.02** | 67% | 40% | 28.14*** |

| Sought medical attention | 23% | 8% | 7.59** | 65% | — | — |

| Sought crisis help | 22% | 8% | 7.25** | 62% | — | — |

| Reported to police | 17% | 5% | 6.5l* | 48% | — | — |

| Sought any services | 35% | 15% | l0.02** | 100% | — | — |

| Incapacitation type | l84.48*** | 0.25 | ||||

| Passed out | 9% | 49% | 15% | 15% | ||

| Incapacitated but not passed out | 8% | 51% | 13% | 15% | ||

| Non-incapacitated | 83% | 0% | 72% | 70% | ||

| Pregnancy concerns | 47% | 44% | 0.17 | 55% | 43% | 5.56* |

| HIV concerns | 38% | 34% | 0.44 | 58% | 28% | 38.05*** |

| STD concerns | 41% | 41% | 0.00 | 66% | 29% | 53.47*** |

Note. FR = forcible rape; DAFR/IR = drug- or alcohol-facilitated/incapacitated rape.

p < .05.

p < .0l.

p < .001.

Demographic and most recent incident characteristics of those who sought services are also presented in Table 1. Compared with those who did not seek services, women who sought services were more likely to have an annual household income less than US$20,000, and less likely to have an income greater than US$60,000. Women who sought services were also younger (37.6, SD = 11.9, vs. 45.1, SD = 16.4), reported more fear of injury or death during the incident, and were more likely to have acknowledged the incident as rape, had a history of prior rape, or had concerns about pregnancy, HIV, and STDs as a result of the rape.

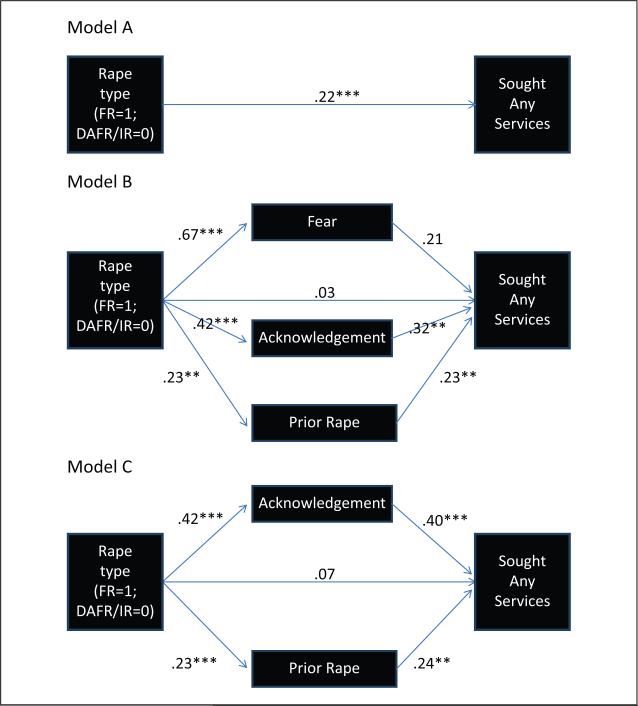

Women with FR were more likely than women with DAFR/IR-only to report seeking services (odds ratio [OR] = 2.99, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [1.47, 6.05]). We identified common potential explanatory mechanisms from bivariate analyses reported above. Specificaly, fear of injury or death during the incident, acknowledgment of the incident as rape, and history of prior rape were the three characteristics that differed both by rape type (FR vs. DAFR/IR-only) and service seeking. These three variables were included in a simultaneous mediation model controlling for age and income. Service seeking was specified as a categorical dependent variable, explanatory variables were allowed to be correlated, and indirect effects were estimated using bootstrapped standard errors (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Model A reflected the direct effect between rape type and service seeking (see Figure 1). The model fit the data well, χ2(df = 3) = 31.97, p < .001, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = 0.001, and accounted for 19% of the variance in service seeking.

Figure 1.

Multivariate models predicting any service seeking from rape type. Model A = standardized direct effect from rape type to service seeking; Model B = standardized direct effects from rape type to potential explanatory variables to service seeking; Model C = trimmed model reflecting standardized direct effects from rape type to potential explanatory variables to service seeking. FR = forcible rape. DAFR/IR = drug or alcohol facilitated/incapacitated rape. *p < .05. **p < .01.***p < .001.

Model B, which included the three potential explanatory variables from the bivariate analyses, fit the data well, χ2(df = 18) = 235.8, p < .001, CFI = 1.0, RMSEA = 0.001, and accounted for 43% of the variance in service seeking (see Figure 1). Rape type was no longer significant after accounting for the explanatory variables. FR was positively associated with fear, rape acknowledgment, and prior rape history, and rape acknowledgment and prior rape history were positively associated with service seeking. However, fear was not significantly associated with service seeking when examined simultaneously with rape acknowledgment and prior rape history (see Model B in Table 2).

Table 2.

Direct and Indirect Effects Model Examining Fear, Rape Acknowledgment, and Prior Rape History as Explanatory Variables in the Path From Rape Type to Service Seeking.

| Unstandardized Estimate | Standard Error | 95% CI | Standardized Estimate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A: Direct effect | ||||

| Rape type > service seeking | 0.94*** | 0.20 | [0.61, 1.27] | 0.22 |

| Model B: Direct effects | ||||

| Rape type > service seeking | –0.10 | 0.30 | [–0.60, 0.40] | –0.03 |

| Rape type > fear | 2.55*** | 0.30 | [2.07, 3.03] | 0.67 |

| Rape type > rape acknowledgment | 1.31*** | 0.19 | [1.00, 1.62] | 0.42 |

| Rape type > prior rape | 0.67*** | 0.17 | [0.38, 0.96] | 0.23 |

| Fear > service seeking | 0.18 | 0.12 | [–0.02, 0.38] | 0.21 |

| Rape acknowledgment > service seeking | 0.32** | 0.11 | [0.13, 0.51] | 0.32 |

| Prior rape > service seeking | 0.24** | 0.09 | [0.09, 0.39] | 0.23 |

| Model B: Indirect effects | ||||

| Rape type > fear > service seeking | 0.46 | 0.31 | [–0.06, 0.97] | 0.14 |

| Rape type > rape acknowledgment > service seeking | 0.42** | 0.16 | [0.16, 0.68] | 0.13 |

| Rape type > prior rape > service seeking | 0.16* | 0.08 | [0.04, 0.29] | 0.05 |

| Model C: Direct effects | ||||

| Rape type > service seeking | 0.23 | 0.22 | [–0.13, 0.59] | 0.07 |

| Rape type > prior rape | 0.67*** | 0.17 | [0.38, 0.96] | 0.23 |

| Rape type > rape acknowledgment | 1.31*** | 0.19 | [1.00, 1.62] | 0.42 |

| Rape acknowledgment > service seeking | 0.41*** | 0.08 | [0.28, 0.55] | 0.40 |

| Prior rape > service seeking | 0.26** | 0.09 | [0.11, 0.41] | 0.24 |

| Model C: Indirect effects | ||||

| Rape type > rape acknowledgment > service seeking | 0.54*** | 0.13 | [0.32, 0.76] | 0.17 |

| Rape type > prior rape > service seeking | 0.17* | 0.08 | [0.05, 0.30] | 0.05 |

Note. 95% CI = 95% confidence interval for unstandardized estimate.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Consistent with recommendations for model trimming (Kline, 2005), we removed fear from Model C (see Figure 1). The trimmed model was a good fit for the data, χ2(df = 12) = 140.8, p < .001, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.012, and accounted for 41% of the variance in service seeking. Significant positive effects emerged between rape type and both rape acknowledgment and prior rape history. In turn, rape acknowledgment and prior rape history were both positively associated with service seeking. Bootstrap analyses revealed significant indirect effects from rape type through rape acknowledgment and prior rape history to service seeking even after controlling for the other explanatory variable. Although both variables served as significant indirect paths from rape type to service seeking, a comparison of these indirect effect coefficients revealed that acknowledgment of the incident as rape was the stronger of the two pathways (difference in unstandardized paths = 0.36, SE = 0.17, p < .05).

Discussion

A substantial proportion of rape victims, particularly those with DAFR/IR experiences only, do not seek medical, crisis, or police services. We found that FR victims had a threefold increased likelihood of seeking any services when compared with women with DAFR/IR-only, and FR victims differed from DAFR/IR-only women on a number of factors including fear of injury or death, memory for the incident, relationship with perpetrator, whether they acknowledged the incident as rape, and whether they had a prior history of rape. However, in simultaneous indirect effect models, only rape acknowledgment and prior rape history were significant explanatory variables in the pathway between rape type and service seeking, and rape acknowledgment was the strongest explanatory variable in the path from rape type to service seeking. The final model accounted for more than 40% of the variance in service seeking.

Our finding that acknowledgment was an important variable in explaining the relationship between rape tactics and service seeking is consistent with rape script theories (e.g., Littleton et al., 2006). DAFR/IR-only was less likely to be acknowledged as rape, potentially because substance involvement does not fit stereotypic rape scripts, including peri-traumatic fear and injury. In addition, DAFR/IR victims reported worse memory for the event, which could interfere with rape acknowledgment. Our findings also support prior research indicating that acknowledgment plays an important role in service-seeking behavior (Kilpatrick et al., 2007; Zinzow & Thompson, 2011). This suggests an opportunity for public health initiatives to target this problem by improving awareness of DAFR/IR as rape.

The fact that prior rape history accounted for part of the relation between rape tactics and service seeking could be due to greater service needs of revictimized women. Women with prior rape histories have increased risk for mental health problems, including PTSD, depression, and substance use disorders (Banyard, Williams, & Siegel, 2001; Gidycz, Coble, Latham, & Layman, 1993; Kilpatrick, Acierno, Resnick, Saunders, & Best, 1997; Walsh et al., 2012). Because FR victims were more likely to report prior rape history, and other studies have found higher prevalence of PTSD and depression among FR victims as compared with DAFR/IR victims (Zinzow et al., 2010), increased mental health needs among these victims may be one factor explaining the positive association between FR and service seeking.

Limitations include the use of retrospective self-report data. Although these models provide support for the associations tested, we are unable to draw temporal conclusions. Furthermore, although prior work with this sample has examined reasons for not reporting incidents to police specifically (e.g., Cohn et al., 2013), variables examined in the current report were not asked explicitly in reference to their decisions around service seeking. Feelings of shame and beliefs that services would not be helpful or might be harmful are common reasons for not seeking services (Patterson, Greeson, & Campbell, 2009). In-depth assessments and inclusion of variables such as shame and self-blame, factors that may be elevated among DAFR/IR victims relative to FR victims, would be helpful to better understand service seeking among women experiencing DAFR/IR-only and FR incidents. Furthermore, due to small cell sizes, we combined DAFR and IR assaults into a single variable; however, future studies should examine whether associations observed here hold for both DAFR-only and IR-only victims as there could be differences in shame and self-blame depending on whether the victim voluntarily consumed substances. Although we drew our sample from a nationally representative sample of women in the United States, the majority of women in the subsample (~75%) were White; therefore, future studies could make efforts to include more ethnically diverse women. Finally, nearly 17% of FR victims had also experienced DAFR/IR rape tactics during the most recent incident. Although preliminary analyses indicated that FR-only and FR + DAFR/IR women evidenced similar associations with important constructs of interest, future studies with larger samples of rape victims may allow for more refined distinctions between groups. Furthermore, to meet DAFR/IR criteria, vaginal, oral, or anal penetration must have been reported, which excluded cases in which the individual was so intoxicated that she was unsure whether penetration occurred. However, this also reduces the likelihood that lower prevalence of rape acknowledgment among victims experiencing DAFR/IR-only type incidents is due to lack of memory of key elements of penetrative assault.

These limitations notwithstanding, several important findings emerged. First, despite equivalent concerns about HIV, STDs, and pregnancy, DAFR/ IR-only victims were less likely than FR victims to seek services, indicating a disparity in service seeking for DAFR/IR-only victims. Second, acknowledgment of the incident as rape and history of prior rape are important drivers of service seeking among FR victims, and rape acknowledgment may be an especially important explanatory variable in the pathway from rape type to service seeking. Public service campaigns designed to increase awareness of DAFR/IR definitions, specifically that DAFR/IR constitutes rape even if force is not present and if victims voluntarily used alcohol or drugs (Kilpatrick et al., 2007), may help to reduce disparities in rape-related service seeking. In addition, education about availability of medical care whether or not the person chooses to report to police, as allowed for in the 2005 Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act (Women, 2005) may be helpful in encouraging more victims of rape to seek medical services. Public education and service agency training should emphasize that medical services, rape crisis advocacy, and options for police reporting are available to victims of DAFR/IR-only as well as to victims of FR.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Manuscript preparation was supported by several grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA023099, T32DA031099). Study data collection was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5R01HD046830) and the National Institute of Justice (2005-WG-BX-0006).

Biography

Kate Walsh, PhD, is now an assistant professor of Psychology at Yeshiva University. Her work focuses on understanding associations between violence, particularly sexual assault, and mental health sequelae. She also has developed and evaluated brief interventions for the prevention of sexual assault within military and college populations.

Heidi M. Zinzow, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Psychology at Clemson University. Her work focuses on identifying risk factors for trauma-related mental health outcomes. She also develops and evaluates violence prevention, service use promotion, and clinical intervention programs for trauma victims.

Christal L. Badour, PhD, is a NIMH-sponsored postdoctoral fellow at the National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina. Her work focuses on understanding the role of emotion expression and regulation in the development, maintenance and treatment of psychopathology following exposure to trauma.

Kenneth J. Ruggiero, PhD, is professor and Co-Director of the Technology Applications Center for Healthful Lifestyles in the College of Nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina. His work has centered around the use of technology-based interventions and provider resources in mental health with emphasis on traumatic stress populations.

Dean G. Kilpatrick, PhD, is Distinguished University Professor and Director of the National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina. He has received numerous federally funded grants and published over 200 articles related to crime victims and traumatic stress-related mental health problems.

Heidi S. Resnick, PhD, is professor of the National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina. She has led several federally funded grants involving the development and rigorous evaluation of early interventions after rape and sexual assault.

Footnotes

The expressed views do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton AM, McAuslan P. Sexual assault and alcohol consumption: What do we know about their relationship and what types of research are still needed? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9:271–303. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(03)00011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Gray M, Best C, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Saunders B, Brady K. Rape and physical violence: Comparison of assault characteristics in older and younger adults in the National Women's Study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:685–695. doi: 10.1023/A:1013033920267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. The long-term mental health consequences of child sexual abuse: An exploratory study of the impact of multiple traumas in a sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:697–715. doi: 10.1023/A:1013085904337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R, Wasco SM, Ahrens CE, Sefl T, Barnes HE. Preventing the “second rape” rape survivors' experiences with community service providers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:1239–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn AM, Zinzow HM, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG. Correlates of reasons for not reporting rape to police: Results from a national telephone household probability sample of women with forcible or drug-or-alcohol facilitated/ incapacitated rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2013;28:455–473. doi: 10.1177/0886260512455515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipas HH, Ullman SE. Child sexual abuse, coping responses, self-blame, posttraumatic stress disorder, and adult sexual revictimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:652–672. doi: 10.1177/0886260506286879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Daigle LE, Cullen FT, Turner MG. Acknowledging sexual victimization as rape: Results from a national-level study. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20:535–574. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Coble CN, Latham L, Layman MJ. Sexual assault experience in adulthood and prior victimization experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1993;17:151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JS, Alexander C, Wynn BN, Rossman L, Dunnuck C. Why women don't report sexual assault to the police: The influence of psychosocial variables and traumatic injury. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2009;36:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.10.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn AS, Jackson J, Kully C, Badger K, Halvorsen J. Calling it rape: Differences in experiences of women who do or do not label their sexual assault as rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2003;27:233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley KD, Campbell R. Moving on or dropping out: Police processing of adult sexual assault cases. Women & Criminal Justice. 2013;23:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, McCauley J. Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study. National Crime Victims Research & Treatment Center, Medical University of South Carolina; Charleston: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Langton L, Berzofsky M, Krebs CP, Smiley-McDonald H. Victimizations not reported to the police, 2006-2010. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Axsom D, Breitkopf CR, Berenson A. Rape acknowledgment and postassault experiences: How acknowledgment status relates to disclosure, coping, worldview, and reactions received from others. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:761–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan T, Evans L, Stevenson E, Jordan CE. Barriers to services for rural and urban survivors of rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2005;20:591–616. doi: 10.1177/0886260504272899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes M, Delmeire L, Mylle J, Altamura C. Risk and preventive factors of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Alcohol consumption and intoxication prior to a traumatic event diminishes the relative risk to develop PTSD in response to that trauma. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2001;63:113–121. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris J, Cubbins LA. Dating, drinking, and rape: Effects of victim's and assailant's alcohol consumption on judgments of their behavior and traits. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1992;16:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson D, Greeson M, Campbell R. Understanding rape survivors' decisions not to seek help from formal social systems. Health & Social Work. 2009;34:127–136. doi: 10.1093/hsw/34.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Holmes MM, Kilpatrick DG, Clum G, Acierno R, Best CL, Saunders BE. Predictors of post-rape medical care in a national sample of women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19:214–219. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D, Campbell JL. Alcohol and rape: The effect of alcohol on attributions of blame for rape. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1982;8:468–476. [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR, Danis F, Mauzy DL, Gallagher SK. Barriers to reporting sexual assault for women and men: Perspectives of college students. Journal of American College Health. 2006;55:157–162. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.3.157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims CM, Noel NE, Maisto SA. Rape blame as a function of alcohol presence and resistance type. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2766–2775. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Sitterle D, Clay G, Kingree J. Reasons for not reporting victimizations to the police: Do they vary for physical and sexual incidents? Journal of American College Health. 2007;55:277–282. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.5.277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchik JA, Probst DR, Irvin CR, Chau M, Gidycz CA. Prediction of sexual assault experiences in college women based on rape scripts: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(2):361–366. doi: 10.1037/a0015157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Filipas HH. Correlates of formal and informal support seeking in sexual assault victims. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:1028–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K, Danielson CK, McCauley JL, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. National prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among sexually revictimized adolescent, college, and adult household-residing women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:935–942. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Resnick HS, McCauley JL, Amstadter AB, Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ. Is reporting of rape on the rise? A comparison of women with reported versus unreported rape experiences in the national women's study-replication. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:807–832. doi: 10.1177/0886260510365869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Women Violence Against. Department of Justice Reauthorization Act of 2005. Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Resnick HS, Barr SC, Danielson CK, Kilpatrick DG. Receipt of post-rape medical care in a national sample of female victims. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Resnick HS, McCauley JL, Amstadter AB, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick DG. The role of rape tactics in risk for posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression: Results from a national sample of college women. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:708–715. doi: 10.1002/da.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzow HM, Thompson M. Barriers to reporting sexual victimization: Prevalence and correlates among undergraduate women. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20:711–725. [Google Scholar]