Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine whether cervical ultrasonic attenuation could identify women at risk of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB). During pregnancy, women (n=67) underwent from one to five transvaginal ultrasonic examinations to estimate cervical ultrasonic attenuation and cervical length. Ultrasonic data were obtained from a Zonare ultrasound system with a 5-9 MHz endovaginal transducer and processed offline. Cervical ultrasonic attenuation was lower at 17-21 weeks gestation in the SPTB group (1.02 dB/cm-MHz) than in the full term birth groups (1.34 dB/cm-MHz), p = 0.04. Cervical length was shorter (3.16 cm) at 22-26 weeks in the SPTB group compared to women delivering full term (3.68 cm), p = 0.004; cervical attenuation was not significantly different at this time point. These findings suggest that low attenuation may be an additional early cervical marker to identify women at risk for SPTB.

Keywords: ultrasonic attenuation, cervical remodeling, preterm birth, cervical length

Introduction

Preterm birth is a major public health challenge. In the United States; one in 8 pregnancies deliver prior to 37 weeks of gestation, which equates to over 447,000 preterm births annually (Martin et al. 2015). Spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) continues to be the primary contributor to long-term morbidity accounting for 75% of neurodevelopmental abnormalities such as cerebral palsy and developmental delay (Goldenberg and Rouse 1998; Lemons et al. 2001; Lorenz 2001). SPTB is recognized as a syndrome that can occur through the activation of many different pathways (Goldenberg and Rouse 1998; Norwitz et al. 1999; Challis et al. 2000; Lemons et al. 2001; Lorenz 2001; Romero et al. 2006; Challis et al. 2009). However, the final common pathway must involve cervical remodeling to allow passage of the fetus through the cervix, and this is the focus of our research.

Ultrasonic cervical length has been the standard measure to identify cervical insufficiency and to identify women who should receive preventive progestogen therapy to prevent preterm birth (Cahill et al. 2010; Campbell 2011; Werner et al. 2011; Romero et al. 2013). Progestogen therapy has shown promise to prevent preterm birth in women with cervical shortening or a history of preterm birth (DeFranco et al. 2007; Fonseca et al. 2007), although the mechanisms of how progestogens prevent preterm birth are poorly understood (Nold et al. 2013). Cervical length assessment has become a widely used clinical measure to identify women at high risk for preterm birth; however, it has low positive predictive value in low-risk women because the majority of individuals identified with a short cervix still deliver at term (Berghella et al. 2009; Romero et al. 2013). Generally, the risk of SPTB is greatest in women with a short cervix compared to women with a longer cervix. (Campbell 2011; Romero et al. 2013). For example, in one study 34.1% of women with a cervical length of ≤1.5 cm before 34 weeks of gestation delivered preterm (Werner et al. 2011). These findings suggest that although a shortened cervix is a risk factor for SPTB, most women with a short cervix will still deliver at term. Although a cervical length measure is more objective than a digital exam of the cervix by palpation (Rozenberg 2008), there continues to be a need for improved noninvasive methods to detect early changes in the cervix associated with SPTB (Garfield et al. 1998; Tekesin et al. 2003; Garfield et al. 2005; Gennisson et al. 2010; Feltovich et al. 2012).

Our research sought to detect the likelihood of SPTB by examining cervical tissue microstructure via estimates of ultrasonic attenuation. Ultrasonic attenuation is a measure of the loss of ultrasonic energy as a function of distance (Shung and Thieme 1993). Ultrasonic attenuation is related to tissue properties of water content, collagen content and organization; which markedly change during cervical remodeling in pregnancy (Pohlhammer and O’Brien 1981; Hall et al. 2000a; Hall et al. 2000b; Hall et al. 2000c; Baldwin et al. 2007). We hypothesized that cervical ultrasonic attenuation could detect changes in water concentration and collagen organization as the cervix remodels (Leppert 1995; Leppert et al. 2000; Feltovich et al. 2005; Garfield et al. 2005; Clark et al. 2006) and hence be an early indicator for preterm birth. Previously we reported that cervical ultrasonic attenuation was lower in women who delivered spontaneously preterm versus term; and women with low attenuation values delivered earlier than women with higher attenuation values (McFarlin et al. 2010). We also evaluated inter-rater reliability of cervical attenuation in 13 subjects. The correlation coefficient was r = 0.91, p<0.001, indicating strong inter-rater reliability.

Considerable ultrasonic attenuation research has been conducted in animals and humans by our group (O’Brien 1977; McFarlin et al. 2006; McFarlin et al. 2010; Bigelow et al. 2011; Labyed and Bigelow 2011; Labyed et al. 2011) and others (Hall et al. 2000b; Feltovich et al. 2010; Feltovich and Hall 2013) to develop, validate and improve methods to detect microstructural tissue changes in biological tissues. For more than four decades, we have known that connective tissue has been related to ultrasonic propagation properties such as the attenuation coefficient (Fields and Dunn 1973; O’Brien 1977). In particular, collagen concentration and water concentration have been inversely related to attenuation in animal cervix tissue (McFarlin et al. 2006; Bigelow et al. 2008; McFarlin et al. 2010; Labyed and Bigelow 2011; Labyed et al. 2011). It was thus appropriate to consider the role of connective tissue and collagen remodeling relative to attenuation in collagenous tissues such as the cervix. In our in vivo animal studies using timed-pregnant rats, significant correlations were found between the cervical attenuation coefficient and gestational age (r = −0.37, p < 0.01) and tropocollagen (r = 0.35, p < 0.001). Also, from 15 to 21 days of pregnancy in the rat, soluble collagen concentration and hydroxyproline decreased by 30% [F (4,31) = 7.5, p < 0.001], insoluble collagen decreased by 25% [F (4,31) = 6.5, p < 0.001], and water concentration increased from 79% on day 15, to 86% on days 20-21 [F (4,31) = 12.1, p < 0.001]. Rats typically deliver on day 21 of pregnancy. These biochemical constituents are consistent with the biology of cervical remodeling during pregnancy (Bigelow et al. 2008). Thus, with this pilot study, our cervical attenuation findings are consistent with what has previously been observed. These promising findings led to the present study reported herein. The purpose of this study was to determine whether ultrasonic attenuation estimates of the cervix have the potential to identify women at risk of SPTB.

Methods

Sixty-seven pregnant African-American women were recruited for the study. Women were eligible if they were: ≥ 18 years of age; able to read, write and understand English; did not have an immune disorder; did not use corticosteroids or have preexisting diabetes; and agreed to undergo transvaginal ultrasonic examinations at 5 planned time-points (17-21, 22-25, 26-29, 30-34, 35-39 weeks gestation) during pregnancy. Women were recruited in the prenatal care clinics and excluded if they had an anomalous fetus or were too ill to give informed consent.

Women underwent from one to five transvaginal ultrasonic examinations (z.one, Zonare Medical Systems, Mountain View, CA) with a clinical 5-9 MHz endovaginal transducer to estimate cervical ultrasonic attenuation and cervical length. Immediately following each cervical scan, using the same ultrasound system settings, a Gammex (Gammex Inc., Middleton, WI) tissue-mimicking reference phantom was scanned. The reference tissue-mimicking phantom had a known attenuation of 0.6 dB/cm-MHz from the manufacturer; as well as from independent validation measurements taken in our laboratory. The processing steps required a calibrated/standardized reference phantom in order to cancel out machine and operator dependencies, thus yielding ultrasonic attenuation estimates that were solely a function of the tissue under study. Women did not undergo a pelvic exam for this study.

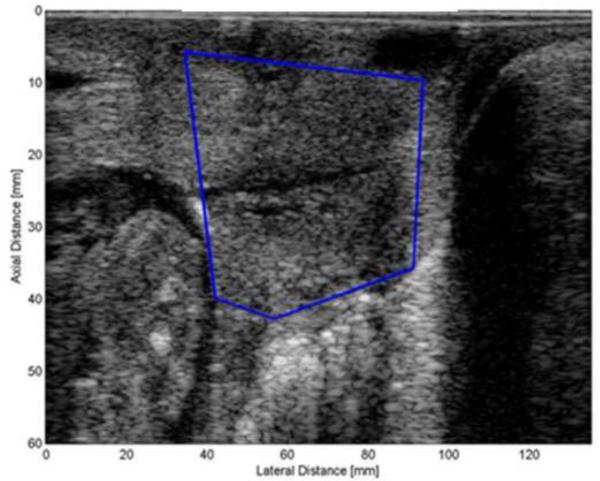

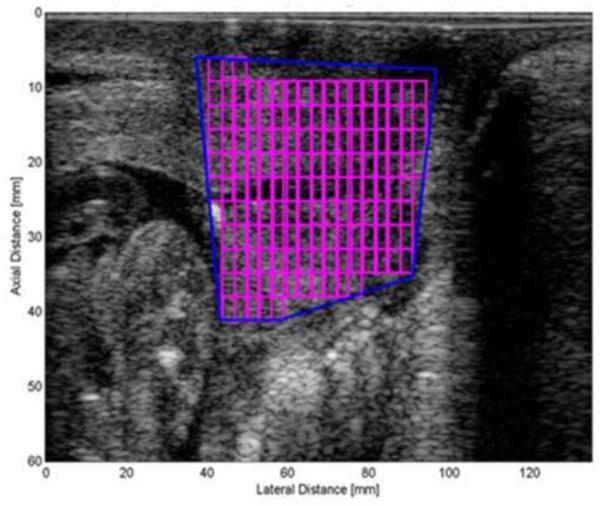

Basic ultrasonic data were obtained, saved and converted to radio frequency (RF) data. The RF data were windowed into smaller regions of interest (ROIs) to estimate the attenuation throughout the entire cervix. In earlier studies (McFarlin et al. 2010), the most homogeneous appearing area of the cervix was selected from the grey-scale image. However, there were concerns about ROI selection bias and measure reproducibility. Therefore, our approach now, and used herein, has been to map the entire cervix and use a mean attenuation value of the entire cervix. Figure 1 displays the process of segmenting the portion of the cervix in a B-mode image that would include all of the attenuation ROIs. The spectral log difference method was used to estimate attenuation (Labyed et al. 2011). This method was selected because among the different algorithms for attenuation estimation, the spectral log difference method is one of the least susceptible to the natural heterogeneity of biological tissues (Bigelow et al. 2011; Labyed and Bigelow 2011).

Figure 1.

a. Figure displays how the examiner outlines the portion of the cervix that will be processed for attenuation.

Figure 1.b. Figure displays the Regions of Interest within the segmented cervix..

All data were entered into an electronic database and analyzed with IBM SPSS 19.0 statistical software (IBM SPSS, Armonk, NY) and R version 3.0.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). Descriptive statistics were reported. ANOVA tests were used to determine patient characteristic differences by group, with α set at 0.05. Two-tailed unpaired t tests were used to determine differences in attenuation and cervical length at 17-21 and 22-26 weeks gestation. Logistic regression modeling was conducted to determine odds ratios of preterm birth, with adjustment for repeated measures using generalized estimating equations analysis using exchangeable working correlation and robust standard errors calculated using the sandwich formula (Liang and Zeger 1986). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis of the logistic regression model was conducted using the lroc function in the R package epicalc (Chongsuvivatwong 2012). This study was approved by the Human Subjects Review Board of the University of Illinois at Chicago. All research participants received written informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Results

All of the women in our study were African American and received their prenatal care at a tertiary medical center with maternal fetal medicine physicians or certified nurse midwives. Most women were multi-gravid (56/67, 84%) and 34% (23/67) had a history of at least one prior preterm birth. Of the 67 women in the study, delivery data were available as follows: 51 (76%) delivered full term, 10 (15%) delivered spontaneously preterm and 6 (9%) delivered preterm due to medical indications such as hypertension, preeclampsia or bleeding. Table 1 displays patient characteristics by group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of women in the study. Differences among the groups were evaluated with an ANOVA test. (m= mean; SD= Standard deviation; SPTB = spontaneous preterm birth; MI PTB = Medically indicated Preterm birth; g= grams)

| Patient characteristics |

Full term N=51 |

SPTB N=10 |

MI PTB N=6 |

Statistic

F |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (m ± SD) | 26 (6) | 25(5) | 30 (9) | 1.279 | 0.285 |

| Number of total | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1.568 | 0.216 |

| pregnancies (m) | |||||

| Number of births: | |||||

| Full term (m) | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | .287 | 0.751 |

| Preterm (m) | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 4.651 | 0.023 |

| Abortion (m) | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.791 | 0.196 | |

| Living children (m) | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 0.526 | 0.541 |

| Number of women | 9 | 6 | 1 | 5.928 | 0.013 |

| who received 17- OHPC |

38.9 (1) | 29.3(6) | 33.1 (1) | 47.383 | 0.0001 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks, ±SD) |

3133 (531) | 1645 | 2046 | 23.49 | 0.0001 |

| Infant Birth weight (g, ±SD ) |

(1202) | (845) |

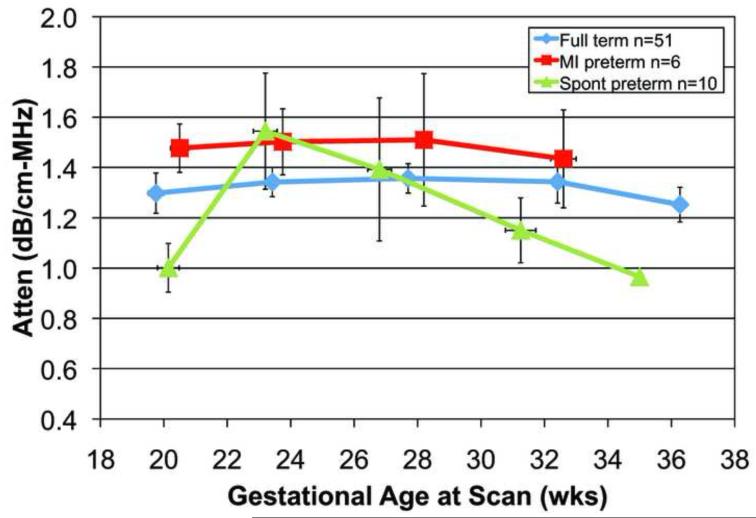

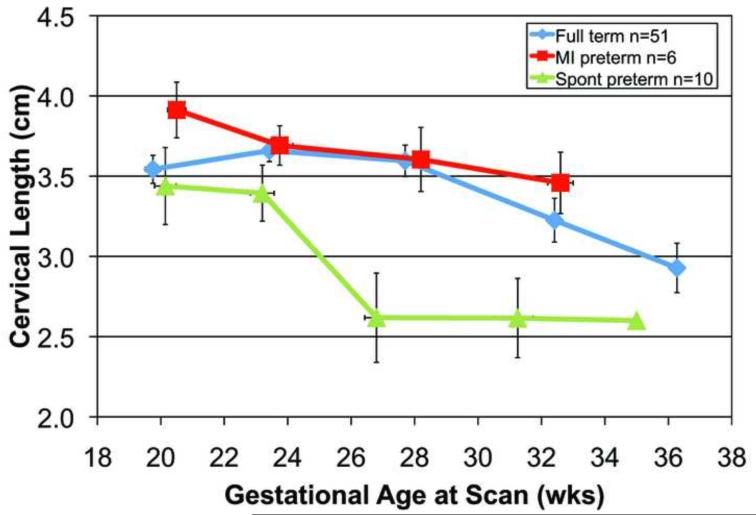

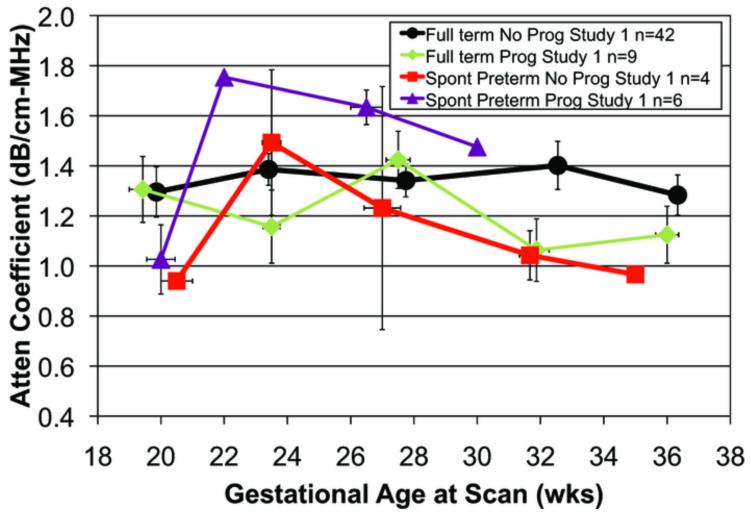

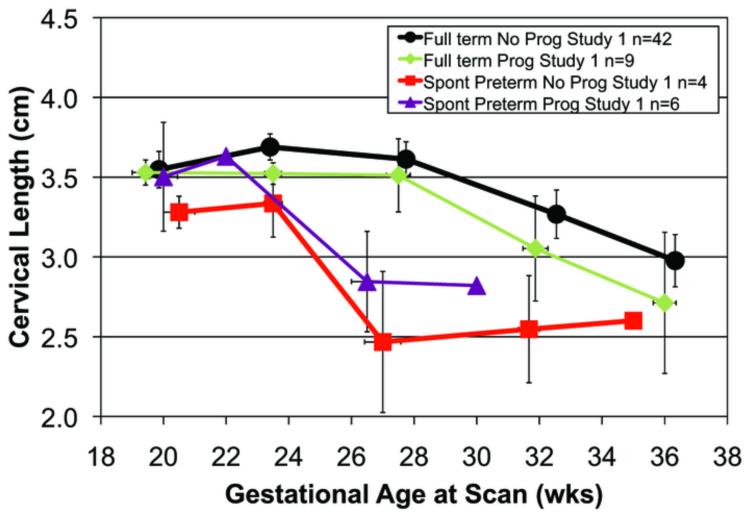

A total of 239 transvaginal ultrasonic examinations were conducted for attenuation and cervical length. Each woman had from one to five scans during pregnancy. The reasons for the missed scans were: preterm birth, missed appointments, moved away, or delivery for medical indications. Figure 2a. displays mean cervical attenuation and mean cervical length for all of the women in the study over the course of pregnancy. For women who delivered full term, attenuation remained relatively constant with a small standard error of the mean until about 36 weeks gestation, when there was a decline. Women delivering spontaneously preterm and medically indicated preterm had different patterns of attenuation over the course of pregnancy.

Figure 2.

a. Attenuation coefficient over the course of pregnancy for 68 African-American women by birth outcome (full term, medically indicated preterm and spontaneous preterm). Error bars are SEM.

Figure 2. b. Cervical length over the course of pregnancy for 67 African-American women by birth outcome (full term, medically indicated preterm and spontaneous preterm). Error bars are SEM.

The analyses focused on the early gestational ages, namely, 17-21 and 22-26 weeks gestation, for cervical attenuation and cervical length outcomes. At 17-21 weeks gestation there were significant attenuation differences between SPTB and full term birth groups, p = 0.04. A sub-group analysis was conducted with 33 separate women who underwent a transvaginal scan of the cervix at the 17-21 weeks gestation time point. Seven of the 33 women delivered spontaneously preterm had a lower mean attenuation (1.02 dB/cm-MHz) than in the full term birth groups (1.34 dB/cm-MHz), p = 0.04. At this time-point, there was little difference in attenuation between the full term and the medically indicated preterm groups.

Importantly, if the true case is a full term delivery and a false case is a spontaneous preterm delivery, then at a threshold attenuation of 1.15 dB/cm-MHz (above this value is true, or full term delivery) for 17-21 weeks gestation, the specificity = 71.4%, sensitivity = 69.2% PPV = 90% and NPV = 38.5%. The 1.15 dB/cm-MHz threshold was selected because it was approximately the half-way value between full term and preterm mean attenuation values.

There were no significant differences in cervical length (Fig 2.) among the three groups at the 17-21 weeks gestation time-point, p = 0.46; there also was no difference in cervical length between the spontaneous preterm and full term birth groups, p = 0.39. Cervical length at 17-21 weeks was not correlated with gestational age at delivery, r = 0.06, p = 0.66. When considering cervical length at the 22-26 weeks gestation time-point (full term n = 49 and spontaneous preterm n = 8), women who delivered preterm had significantly shorter cervical lengths (3.16 cm) than women delivering full term (3.68 cm), t = 3.04, p = 0.004. None of the women in the study had cervical lengths <2.5 cm before 27 weeks, a common definition of a “short cervix” (Romero et al. 2013). These findings suggest that cervical tissue properties, as detected by attenuation, are sensitive to remodeling by 17-21 weeks in women who will deliver spontaneously preterm, and before cervical shortening.

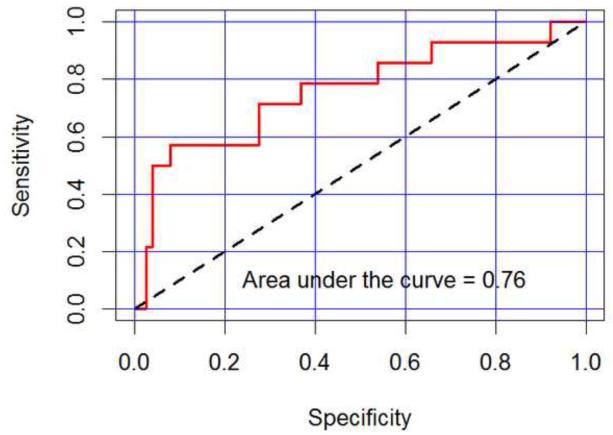

The data were filtered to extract all measurements for each patient in the range 17-26 weeks gestation (full term n = 49 patients with 76 visits, spontaneous preterm n = 10 patients with 14 visits, range 17-26 weeks gestation). A logistic regression model with exchangeable correlation structure was calculated to model the log odds of preterm birth as a function of scan attenuation, cervical length, an indicator for measurements prior to 22 weeks and the interaction between attenuation and the indicators for measurements prior to 22 weeks. The indicator for measurements prior to 22 weeks and the interaction effect enabled estimation of separate logistic regression response curves for attenuation prior to 22 weeks versus after 22 weeks. The attenuation interaction coefficient was approaching statistical significance (p = 0.053), with an estimated ratio of odds ratios of 1.89 (90% confidence interval from 1.10 to 3.25), suggesting an association between low early attenuation measurements and preterm birth. Cervical length was not statistically significant in the model, but suggestive of association between low cervical length and preterm birth (p=0.12), with an estimated odds ratio of 1.75 (90% confidence interval from 0.975 to 3.14). Using the logistic regression model as a classifier for full term versus preterm birth, the receiver-operator curve (ROC) is displayed in Figure 3. The estimated 76.0% area under the curve (AUC) is the estimated probability of correctly classifying two randomly selected patients, one of whom delivers preterm and the other who does not, suggesting some predictive capability based on the measurements 26 weeks and earlier.

Figure 3.

Receiver Operator Curve for the logistic regression model (attenuation and cervical length) based on first-visit data only at 20.5±3.5 weeks gestation. The model accounts for 76% of the area under the curve (red line)

Fifteen women received weekly 17-α hydroxy-progesterone caproate [17-OHPC] injections during pregnancy due to a history of a prior preterm birth. No women in the study received vaginal progesterone. The mean gestational age was 16 weeks when 17-OHPC was initiated. Of the 15 women with a history of preterm birth, six delivered preterm. To further understand attenuation and cervical length for women who were and were not treated without 17-OHPC, Figure 4 displays delivery outcomes for those with/without 17-OHPC. However, the sample sizes were too small to yield any conclusions.

Figure 4.

a. Attenuation coefficient over the course of pregnancy for 61 African-American women by birth outcome and 17-OHPC. The medically indicated preterm birth group (n = 6) was not included. Error bars are SEM. 17-OHPC = 17 hydroxyprogesterone caproate.

Figure 4.b. Cervical length over the course of pregnancy for 6 African-American women by birth outcome and 17-OHPC. The medically indicated preterm birth group (n = 6) was not included. Error bars are SEM. 17-OHPC = 17 hydroxyprogesterone caproate.

Discussion

The results of this pilot study suggest that for women who will deliver spontaneously preterm, ultrasonic attenuation was lower at the 17-21 weeks gestation time-point and before cervical length changes were detected at the 22-26 weeks gestation time-point. None of the women in our study had a cervical length less than 2.5 cm before 27 weeks of pregnancy. A cervical length less than 2.5 cm is a commonly used clinical cut-point for identifying women at risk for SPTB and eligibility for progestogen therapy (Campbell, 2011). The ultrasonic attenuation estimates of the cervix significantly provided SPTB risk assessment at the 17-21 weeks gestation time-point, weeks before the cervix shortened in length. The high positive predictive value of attenuation (PPV = 90%) at the first time-point (17-21 weeks) to determine which women will deliver spontaneously preterm is encouraging. Our data suggest that for women who will deliver full term, attenuation of the cervix is high at 17-21 weeks and remains fairly stable throughout pregnancy.. Presently the PPV of cervical length in low risk women ranges from 25 – 52%, although it is the current standard of care (Romero et al. 2013). It is possible that cervical length and attenuation estimates of the cervix may detect different groups of women at risk for preterm birth, as none of the women in our study had a cervical length less than 2.5 cm before 27 weeks gestation.

Limitations

This pilot study had several limitations. Human research is important for translating our basic science animal findings to clinical practice in humans, but is relatively expensive. Therefore, the sample size was small, especially with the number of women delivering spontaneously preterm. Not all women kept their appointments to be scanned at the five time points. The findings will provide data for sample size and effect size estimates to conduct a more focused study with a greater number of spontaneous preterm births. Our sample also only included African American women who have an increased incidence of spontaneous preterm births compared to white women.

Conclusions

Quantitative ultrasound technology has the capability to take cervical assessment and preterm birth risk beyond the present macrostructure cervical length measures. In this study, none of the women had a short cervix (<2.5 cm) before 27 weeks gestation, yet 10 women had low attenuation of the cervix at 17-21 weeks gestation and delivered preterm. These findings suggest that low attenuation may be an additional early cervical marker for preterm birth risk. Further research with a larger sample size will be needed to determine whether cervical attenuation estimates during pregnancy have the potential to be clinically useful to predict women early in pregnancy at risk for SPTB. The process of cervical remodeling during pregnancy makes attenuation estimates particularly attractive as a noninvasive method to detect tissue changes that reflect early preparation and readiness for labor and birth. The cervix microstructure of collagen content and organization; and tissue composition of water and proteoglycan content markedly change during pregnancy (Leppert and Yu 1991; Leppert 1995; Leppert et al. 2000; Word et al. 2007). As composition of the cervix changes from a firm to a supple soft structure ultrasonic attenuation estimates can provide clinicians early tissue based information, rather than waiting for symptoms of preterm birth. Ultrasonic attenuation estimates could be an added feature added to clinical ultrasound systems.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded in part by a grant from the Irving Harris Foundation, the University of Illinois College of Nursing Internal Research Support Program, NIH grant 1R21HD062790 and the University of Illinois Center for Clinical and Translational Science (NIH grant UL1TR000050). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We thank Ellora Sen-Gupta and Tara Peters for their work as Research Assistants on the project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baldwin SL, Yang M, Marutyan KR, Wallace KD, Holland MR, Miller JG. Ultrasonic detection of the anisotropy of protein cross linking in myocardium at diagnostic frequencies. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 2007;54:1360–9. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghella V, Baxter JK, Hendrix NW. Cervical assessment by ultrasound for preventing preterm delivery. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2009:CD007235. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007235.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow TA, Labyed Y, McFarlin BL, Sen-Gupta E, O’Brien WDJ. Comparison of algorithms for estimating ultrasound attenuation when predicting cervical remodeling in a rat model. Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Internat Symposium Biomed Imaging. 2011:883–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow TA, McFarlin BL, O’Brien WD, Jr, Oelze ML. In vivo ultrasonic attenuation slope estimates for detecting cervical ripening in rats: Preliminary results. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2008;123:1794–800. doi: 10.1121/1.2832317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow TA, O’Brien WD. Evaluation of the spectral fit algorithm as functions of frequency range and deltakaeff. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 2005a;52:2003–10. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2005.1561669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow TA, O’Brien WD., Jr A Model for Estimating Ultrasound Attenuation along the Propagation Path to the Fetus from Backscattered Waveforms J Acoust Socf Amer. 2005b;118:1210–20. doi: 10.1121/1.1945564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow TA, O’Brien WD., Jr Impact of local attenuation approximations when estimating correlation length from backscattered ultrasound echoes. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2006;120:546–53. doi: 10.1121/1.2208456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow TA, Oelze ML, O’Brien WD., Jr Estimation of total attenuation and scatterer size from backscattered ultrasound waveforms. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2005;117:1431–9. doi: 10.1121/1.1858192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bly S, Van den Hof MC. Obstetric ultrasound biological effects and safety. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27:572–80. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30716-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill AG, Odibo AO, Caughey AB, Stamilio DM, Hassan SS, Macones GA, Romero R. Universal cervical length screening and treatment with vaginal progesterone to prevent preterm birth: a decision and economic analysis. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:548, e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S. Universal cervical-length screening and vaginal progesterone prevents early preterm births, reduces neonatal morbidity and is cost saving: doing nothing is no longer an option. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:1–9. doi: 10.1002/uog.9073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis JR, Lockwood CJ, Myatt L, Norman JE, Strauss JF, 3rd, Petraglia F. Inflammation and pregnancy. Reprod Sci. 2009;16:206–15. doi: 10.1177/1933719108329095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. 21, 514–550.[Endocrine and paracrine control of birth at term and preterm. Endocrine Rev. 2000;21:514–50. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K, Ji H, Feltovich H, Janowski J, Carroll C, Chien EK. Mifepristone-induced cervical ripening: structural, biomechanical, and molecular events. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFranco EA, O’Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Fusey S, Soma-Pillay P, Porter K, How H, Schakis R, Eller D, Trivedi Y, Vanburen G, Khandelwal M, Trofatter K, Vidyadhari D, Vijayaraghavan J, Weeks J, Dattel B, Newton E, Chazotte C, Valenzuela G, Calda P, Bsharat M, Creasy GW. Vaginal progesterone is associated with a decrease in risk for early preterm birth and improved neonatal outcome in women with a short cervix: a secondary analysis from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology : the official journal of the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:697–705. doi: 10.1002/uog.5159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltovich H, Hall TJ. Quantitative imaging of the cervix: setting the bar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2013;41:121–8. doi: 10.1002/uog.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltovich H, Hall TJ, Berghella V. Beyond cervical length: emerging technologies for assessing the pregnant cervix. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:345–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltovich H, Ji H, Janowski JW, Delance NC, Moran CC, Chien EK. Effects of selective and nonselective PGE2 receptor agonists on cervical tensile strength and collagen organization and microstructure in the pregnant rat at term. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:753–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltovich H, Nam K, Hall TJ. Quantitative ultrasound assessment of cervical microstructure. Ultrason Imaging. 2010;32:131–42. doi: 10.1177/016173461003200302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields S, Dunn F. Correlation of echographic visualizability of tissue with biological composition and physiological state. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1973;54:809–12. doi: 10.1121/1.1913668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. NEJM. 2007;357:462–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RE, Chwalisz K, Shi L, Olson G, Saade GR. Instrumentation for the diagnosis of term and preterm labour. J Perinat Med. 1998;26:413–36. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1998.26.6.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield RE, Maner WL, Maul H, Saade GR. Use of uterine EMG and cervical LIF in monitoring pregnant patients. BJOG. 2005;112(Suppl 1):103–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gennisson JL, Deffieux T, Mace E, Montaldo G, Fink M, Tanter M. Viscoelastic and anisotropic mechanical properties of in vivo muscle tissue assessed by supersonic shear imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36:789–801. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giurgescu C, Kavanaugh K, Norr KF, Dancy BL, Twigg N, McFarlin BL, Engeland CG, Hennessy MD, White-Traut RC. Stressors, resources, and stress responses in pregnant African American women: a mixed-methods pilot study. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2013;27:81–96. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e31828363c3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. Prevention of premature birth. NEJM. 1998;339:313–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CS, Dent CL, Scott MJ, Wickline SA. High-frequency ultrasound detection of the temporal evolution of protein cross linking in myocardial tissue. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control. 2000a;47:1051–8. doi: 10.1109/58.852089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CS, Nguyen CT, Scott MJ, Lanza GM, Wickline SA. Delineation of the extracellular determinants of ultrasonic scattering from elastic arteries. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000b;26:613–20. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CS, Scott MJ, Lanza GM, Miller JG, Wickline SA. The extracellular matrix is an important source of ultrasound backscatter from myocardium. J Acoustl Soc Amer. 2000c;107:612–9. doi: 10.1121/1.428327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labyed Y, Bigelow TA. A theoretical comparison of attenuation measurement techniques from backscattered ultrasound echoes. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2011;129:2316–24. doi: 10.1121/1.3559677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labyed Y, Bigelow TA, McFarlin BL. Estimate of the attenuation coefficient using a clinical array transducer for the detection of cervical ripening in human pregnancy. Ultrasonics. 2011;51:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lau TY, Sangha HK, Chien EK, McFarlin BL, Wagoner Johnson AJ, Toussaint KC., Jr Application of Fourier transform-second-harmonic generation imaging to the rat cervix. J Micro. 2013;251:77–83. doi: 10.1111/jmi.12046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Oh W, Korones SB, Papile LA, Stoll BJ, Verter J, Temprosa M, Wright LL, Ehrenkranz RA, Fanaroff AA, Stark A, Carlo W, Tyson JE, Donovan EF, Shankaran S, Stevenson DK. Very low birth weight outcomes of the National Institute of Child health and human development neonatal research network, January 1995 through December 1996. NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert PC. Anatomy and physiology of cervical ripening. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1995;38:267–79. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199506000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppert PC, Kokenyesi R, Klemenich CA, Fisher J. Further evidence of a decorin-collagen interaction in the disruption of cervical collagen fibers during rat gestation. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:805–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70329-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz JM. The outcome of extreme prematurity. Seminars Perinatol. 2001;25:348–59. doi: 10.1053/sper.2001.27164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud H, Wagoner Johnson A, Chien EK, Poellmann MJ, McFarlin B. System-level biomechanical approach for the evaluation of term and preterm pregnancy maintenance. J Biomech Engineer. 2013;135:021009. doi: 10.1115/1.4023486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman JK, Wilson EC, Mathews MS. Births: Final Data for 2010. Nat Vital Stat Report. 2012;61:1–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlin BL, Bigelow TA, Laybed Y, O’Brien WD, Oelze ML, Abramowicz JS. Ultrasonic attenuation estimation of the pregnant cervix: a preliminary report. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36:218–25. doi: 10.1002/uog.7643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlin BL, O’Brien WDJ, Oelze ML, Zachary JF, White-Traut RC. Quantitative ultrasound assessment of the rat cervix. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:1031–40. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.8.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K, Rosado-Mendez IM, Wirtzfeld LA, Ghoshal G, Pawlicki AD, Madsen EL, Lavarello RJ, Oelze ML, Zagzebski JA, O’Brien WD, Jr., Hall TJ. Comparison of ultrasound attenuation and backscatter estimates in layered tissue-mimicking phantoms among three clinical scanners. Ultrason Imaging. 2012a;34:209–21. doi: 10.1177/0161734612464451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K, Rosado-Mendez IM, Wirtzfeld LA, Kumar V, Madsen EL, Ghoshal G, Pawlicki AD, Oelze ML, Lavarello R, Bigelow TA, Zagzebski JA, O’Brien WDJ, Hall TJ. Cross-imaging system comparison of backscatter coefficient estimates from a tissue-mimicking material. J Acoust Soc Amer. 2012b;132:1319–24. doi: 10.1121/1.4742725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K, Rosado-Mendez IM, Wirtzfeld LA, Pawlicki AD, Madsen EL, Lavarello R, Oelze ML, Zagzebski JA, O’Brien WDJ, Hall TJ. Comparison of Ultrasound Attenuation and Backscatter Estimates in Layered Tissue Mimicking Phantoms among Three Clinical Scanners. Ultrasonic Imag. 2012c;34:209–21. doi: 10.1177/0161734612464451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K, Zagzebski JA, Hall TJ. Quantitative Assessment of In Vivo Breast Masses Using Ultrasound Attenuation and Backscatter. Ultrasonic Imaging. 2013;35:146–61. doi: 10.1177/0161734613480281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nold C, Maubert M, Anton L, Yellon S, Elovitz MA. Prevention of preterm birth by progestational agents: what are the molecular mechanisms? Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:223, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwitz ER, Robinson JN, Challis JR. The control of labor. NEJM. 1999;341:660–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien WD., Jr. The Relationship between Collagen and Ultrasonic Attenuation and Velocity in Tissue. Proc Ultrason Internat. 1977;77:194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Poellmann MJ, Chien EK, McFarlin BL, Wagoner Johnson AJ. Mechanical and structural changes of the rat cervix in late-stage pregnancy. J Mechanl Behav Biomed Mat. 2013;17:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohlhammer J, O’Brien WD., Jr Dependence of the ultrasonic scatter coefficient on collagen concentration in mammalian tissues. J Acoust Soc Amer. 1981;69:283–5. doi: 10.1121/1.385349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Hassan S, Erez O, Chaiworapongsa T, Mazor M. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113(Suppl 3):17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Yeo L, Miranda J, Hassan SS, Conde-Agudelo A, Chaiworapongsa T. A blueprint for the prevention of preterm birth: vaginal progesterone in women with a short cervix. J Perinat Med. 2013;41:27–44. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2012-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenberg P. The secret cervix. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:126–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.6132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shung KK, Thieme GA. Biologic tissues as ultrasonic scattering media. In: Shung KK, Thieme GA, editors. Ultrasonic Scattering in Biologic Tissues. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1993. pp. 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- Tekesin I, Hellmeyer L, Heller G, Romer A, Kuhnert M, Schmidt S. Evaluation of quantitative ultrasound tissue characterization of the cervix and cervical length in the prediction of premature delivery for patients with spontaneous preterm labor. Amer J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:532–9. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner EF, Han CS, Pettker CM, Buhimschi CS, Copel JA, Funai EF, Thung SF. Universal cervical length screening to prevent preterm birth: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:32–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.8911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Word RA, Li XH, Hnat M, Carrick K. Dynamics of cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition: mechanisms and current concepts. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:69–79. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-956777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]