Summary

Work in mice indicates that innate functions of mast cells, particularly degradation of venom toxins by mast cell-derived proteases, can enhance resistance to certain arthropod or reptile venoms. Recent reports indicate that acquired Th2 immune responses associated with the production of IgE antibodies, induced by Russell’s viper venom or honeybee venom, or by a component of honeybee venom, bee venom phospholipase 2 (bvPLA2), can increase the resistance of mice to challenge with potentially lethal doses of either of the venoms or bvPLA2. These findings support the conclusion that, in contrast to the detrimental effects associated with allergic Th2 immune responses, mast cells and IgE-dependent immune responses to venoms can contribute to innate and adaptive resistance to venom-induced pathology and mortality.

Introduction

Venoms from diverse animal species, including honeybees, wasps, scorpions, ants, Portuguese man-of-war, snakes, lizards, and the platypus can directly induce mast cell (MC) activation and degranulation [1–4]. Venom-induced release of granule-associated mediators by MCs has been thought to contribute to the symptoms associated with envenomation because some of these MC-derived mediators can increase vascular permeability (enhancing systemic dissemination of venom toxins), promote local recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells, influence clotting and fibrinolysis, and induce shock [5]. Moreover, many components of venoms also are “allergens” that can induce host sensitization via induction of Th2 immune responses and production of venom-specific Immunoglobulin E (IgE). Indeed, humans that have been sensitized with venoms can develop MC- and IgE-associated allergic reactions, including fatal anaphylaxis, upon subsequent venom exposure [6–12].

Such findings have supported the conclusion that venomous animals exploit to their own advantage the biological activities of the host’s MCs and IgE, recruiting these components of innate and adaptive immunity to increase the toxicity of the venom. In 1991, Margie Profet suggested an alternative interpretation of the evidence indicating that MCs and IgE participate in immune responses to venoms, proposing that these components of innate and adaptive immunity may function to enhance rather than impair host resistance to venoms and, potentially, other toxins [13]. We review herein recent lines of evidence from studies in mice supporting the conclusion that both the innate functions of MCs and IgE-dependent Th2 immunity can be beneficial rather than detrimental in host responses to the venoms of some arthropods or reptiles.

Mast cells in innate resistance to envenomation

Higginbotham suggested in 1965 and 1971 that MCs, which are numerous in the skin, might enhance resistance to environmental noxious insults, such as bee stings [2] or snake bites [14]. He reported evidence that heparin, a highly anionic proteoglycan stored in MC granules, can neutralize venom toxicity by binding highly cationic components of the venoms, such as melittin in bee venom. This work was done before knock-out or MC-deficient mice had been described, and even now it is difficult to analyze the role of MC heparin using genetic approaches because mice deficient in heparin express many other phenotypic abnormalities including reduced storage of proteases in MC granules [15].

However, the beneficial role of MCs in enhancing resistance to venoms hypothesized by Higginbotham was later supported by studies of innate responses to venoms or venom components in MC-deficient mice [1,4], mice lacking specific MC proteases [1,4], and mice in which the MC protease, carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3), was rendered catalytically inactive [16]. For example, MC-deficient C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh mice (whose MC deficiency is caused by a mutation affecting expression of Kit, the receptor for the MC survival and maturation factor stem cell factor [4,17]) and C57BL/6-Cpa3-Cre+-Mcl-1fl/fl mice [17] (whose marked MC deficiency and decreased numbers of basophils are not due to c-kit mutations [18]) were significantly more susceptible to challenge with a potentially lethal dose of honeybee (Apis mellifera) venom (BV) than either wild type or control mice (i.e., littermate Kit+/+ and Cpa3-Cre+-Mcl-1+/+ mice) or MC-deficient mice whose skin had been engrafted with MCs derived in vitro from the corresponding wild type mice. These and other experiments provided compelling evidence that MCs can enhance innate resistance in mice to the morbidity and mortality induced by the whole venoms of the honeybee [4,17], three species of snakes (Israeli Mole Viper, western diamondback rattlesnake, and southern copperhead) [4], the Gila monster lizard [1], and two species of scorpions [1].

While it is possible that MC-derived heparin contributes to the ability of MCs to enhance innate resistance to some venoms (especially those which contain highly cationic toxins), it is now clear that at least two MC-associated proteases, mouse CPA3 and mouse MCPT4 (the mouse chymase with functional similarity to human MC chymase [15]) can have important roles in augmenting innate host resistance to certain arthropod or reptile venoms (Fig. 1). Pharmacological evidence and studies in mice containing MCs that had been treated with shRNA specific for CPA3 suggested that CPA3 is the critical protease responsible for reducing the toxicity of both the whole venom of the Israeli mole viper (Atractaspis engaddensis) and its major toxin, sarafotoxin 6b [4]. The essential role for CPA3 in degrading and enhancing resistance to sarafotoxin 6b was then demonstrated elegantly in experiments employing transgenic mice that produce only a catalytically inactive CPA3 [16]. Notably, both sarafotoxin 6b [4] and its structurally related mammalian molecule, the vasoconstrictor peptide endothelin-1 (ET-1), can induce MC degranulation in mice, and MCs [16,19] and MC-derived CPA3 [4,16] can enhance resistance to the morbidity and mortality associated with the toxicity of either ET-1 or sarafotoxin 6b.

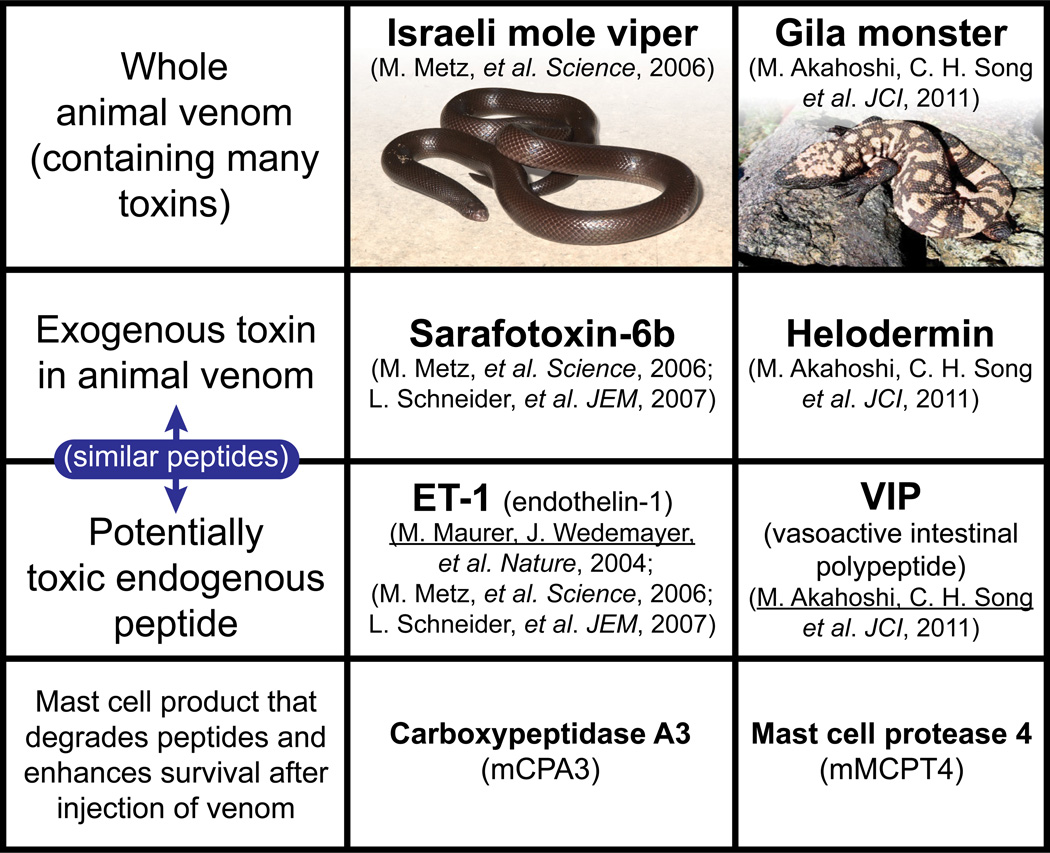

Figure 1. Mast cells can enhance resistance to both high levels of endogenous peptides (helping to restore homeostasis) and structurally similar peptides in reptile venoms.

Mouse MC cytoplasmic granules contain proteases such as carboxypeptidase A3 (mCPA3) and mast cell protease 4 (mMCPT4) that, upon secretion by activated mast cells, can degrade certain endogenous peptides, such as endothelin-1 (ET-1) and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP), respectively, as well as structurally similar peptides contained in the venoms of poisonous reptiles, such as sarafotoxin 6b in the venom of the Israeli mole viper (Atractaspis engaddensis) and helodermin in the venom of the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum). The ability of mast cells to be activated to degranulate by components of venoms such as these, which can act at the same receptors which recognize the corresponding structurally similar endogenous peptides, permits mast cells to release proteases that can reduce the toxicity of these peptides and which thereby help to enhance the survival of mice injected with the whole venoms of these reptiles, that contain many toxins in addition to sarafotoxin 6b and helodermin. This mechanism may also permit mast cells to restore homeostasis in settings associated with markedly increase levels of the endogenous peptides. This is a modified version of Fig. 4 in the review: Rouse-Whipple Award Lecture: The mast cell-IgE paradox: From homeostasis to anaphylaxis, by Stephen J. Galli, reproduced with the permission of the publisher.

The venom of the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum) represents another example of a reptile venom that contains a MC-activating peptide, in this case, helodermin, which has structural and functional similarity to a mammalian peptide, i.e., vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP). However, extensive evidence indicates that it is mouse MCPT4, not CPA3, which is important in diminishing the toxicity of H. suspectum venom, helodermin, and VIP, as well as certain scorpion venoms [1]. These findings support the hypothesis that MCs and MC-derived proteases can contribute to maintaining homeostasis in two distinct settings associated with high levels of peptides that can induce MC activation: 1) Degradation of potentially toxic endogenous peptides, such as ET-1 or VIP, by MCs activated by such peptides via innate receptors expressed on the MC surface; 2) Degradation of toxic exogenous peptides, such as sarafatoxin 6b or helodermin, by MCs activated when such peptides are recognized by the same innate receptors that bind the corresponding mammalian peptide (Fig. 1). In addition to MC-derived proteases and heparin, other MC-derived mediators also have the potential to enhance innate resistance to venoms. For example, mediators that increase local vascular permeability might help to elevate interstitial concentrations of circulating inhibitors of venom metalloproteases and other toxic venom components.

Mechanisms of mast cell activation in innate responses to envenomation

Multiple mechanisms can contribute to MC activation during envenomation. Some venoms contain peptides that are structurally similar to endogenous peptides (e.g., kallikrein, atrial natriuretic peptide, or vascular endothelial growth factor [20]) and that are recognized by innate receptors on the MC surface. For example, ETA and ETB recognize ET-1 and sarafatoxins [4,19] and VPAC1 and VPAC2 recognize VIP and helodermin [21]. Venoms also can contain cytolytic peptides, enzymes (particularly phospholipases, which are present in many venoms), bioactive amines, salts, neurotransmitters, etc. [22]. Cytolytic venom components can mediate cell lysis directly by integration into cell membranes and pore formation (e.g., melittin in BV and cytolytic peptides in scorpion venom) or indirectly (e.g., venom-derived PLA2) by enzymatic cleavage of membrane phospholipids and generation of lysophospholipids [23].

Palm & Medzhitov showed that BV, primarily by its pore-forming peptide, melittin, can induce NLRP3 inflammasome dependent caspase-1 activation and IL-1/IL-1R dependent neutrophil recruitment at sites of BV injection [24]. Although neutrophil depletion did not diminish the pathology or hypothermia induced by western diamondback rattlesnake venom, neutrophils may contribute to tissue repair following envenomation. Experiments employing MC- & caspase-1 double deficient (KitW-sh/W-sh;Casp1−/−) mice suggest that MCs may be involved in caspase-1 dependent protection from envenomation [24], but it is not yet clear whether the NLRP3 inflammasome is involved in venom-induced MC activation in tissues.

MCs can be activated to degranulate at sites of complement activation via C3a or C5a binding to C3aR or C5aR on the MC surface [25]. Since envenomation is often associated with complement activation [26], local production of C3a and C5a may contribute to MC activation at sites of envenomation.

IgE, FcεRI, and mast cells in adaptive immune resistance to envenomation

Allergies, characterized by acquired Th2 immune responses and the production of allergen-specific IgE antibodies [27–29], are widely considered misdirected and maladaptive immune responses, often against otherwise innocuous environmental agents [30,31]. The immediate hypersensitivity reactions which occur in sensitized individuals within moments of allergen exposure range from localized areas of swelling, erythema and itching (in response to cutaneous encounters with the allergen) to catastrophic and sometimes fatal anaphylactic reactions, that can be induced by animal venoms, as well as by foods, drugs, and other seemingly harmless compounds [32,33]. By contrast, IgE-associated Th2 responses are thought to contribute to host defense during infections with certain helminths and other parasites [29,34–36]. However, any other “physiological” roles of IgE have remained obscure.

In 1974, James H. Stebbings proposed that “a major function of immediate hypersensitivity reactions has been the protection of terrestrial vertebrates from the bites of, or invasion by, arthropods” [37]. He hypothesized three advantageous functions of immediate hypersensitivity: 1) the induction of avoidance behavior, 2) protection against immune injury caused by antigen-antibody complexes, and 3) inhibition of delayed hypersensitivity reactions, and also noted that some insects which may induce immediate hypersensitivity, such as tropical mosquitoes, are potential disease vectors [37]. Indeed, if IgE-dependent immediate hypersensitivity reactions to arthropod bites have effects that help hosts to experience fewer bites, this could contribute to diminished transmission of arthropod-borne diseases. In 1991, Margie Profet noted that the common feature of most allergens is their origin from sources (such as nuts, seafood, or venoms) which either might (e.g., foods) or always (e.g., venoms) contain toxins [13]. Profet proposed that allergic reactions (manifested as immediately occurring symptoms, such as coughing or diarrhea) evolved as defense mechanisms which allow the sensitized host to respond immediately to, and to eliminate, neutralize and/or avoid, noxious substances which might be indicative of potentially life-threatening situations [13]. However, Profet’s “toxin hypothesis” only recently gained wide attention [38]. Two recent studies of mice sensitized and challenged with animal venoms [17] or a venom component [39] have now provided experimental support for key aspects of this hypothesis.

We showed that Th2 immunity induced in mice injected with sublethal amounts of the whole venoms of the honeybee or the Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) [17] significantly enhanced the survival of mice later challenged with potentially lethal doses of those venoms. In such Th2 responses to BV, experiments employing passive transfer of IgE-containing or IgE-depleted serum from BV-immunized to naïve mice, as well as studies in mice lacking IgE or the FcεRI α or γ chains, showed that both IgE and functional FcεRI are required for expression of enhanced acquired resistance to the morbidity and mortality induced by BV [17]. Palm et al. investigated Th2 responses to honeybee venom (BV) and several snake venoms, and showed that the Th2 immune responses induced by injections of BV phospholipase A2 (bvPLA2) diminished the drop in body temperature of mice challenged with a potentially lethal amount of bvPLA2 [39]. This beneficial effect of bvPLA2 immunization was significantly reduced in mice that lacked the FcεRI α chain, consistent with a role for IgEFc εRI interactions in enhancing resistance to bvPLA2.

While the intrinsic toxicity of BV reflects the actions of multiple constituents, including cytolytic peptides (e.g., melittin), enzymes (including bvPLA2 and hyaluronidase), neurotoxins and bioactive amines [40], by inducing the development of BV-specific IgE antibodies, honeybee stings can prime some unfortunate individuals to exhibit anaphylaxis in response to even a single sting [10]. In that setting, the pathology induced by the immune response far exceeds that induced by the intrinsic toxicity of the venom. BvPLA2 is the most potent allergic protein in BV (although accounting for only about 12% of the weight of BV [40]) and its enzymatic activity (associated with the conversion of membrane phospholipids into arachidonic acid and lysophospholipids that cause cell lysis) is required for the induction of bvPLA2-specific Th2 [39] and IgE responses [41].

MCs are major FcεRI-expressing IgE effector cells [28,42–44]. As discussed above, MCs contribute importantly to innate resistance to BV and other venoms and venom components [1,4,16]. We found in serum transfer experiments that MC-deficient mice that received immune serum collected from BV-immunized wild type mice exhibited significantly worse survival upon BV challenge compared to those which had been passively immunized with control serum from mock-immunized mice [17]. This result is consistent with the conclusion that MCs can contribute to IgE-mediated enhanced resistance to BV, and also suggests that, in the absence of MCs, components of BV-immune serum may actually exacerbate, rather than ameliorate, the adverse response to BV.

Conclusions

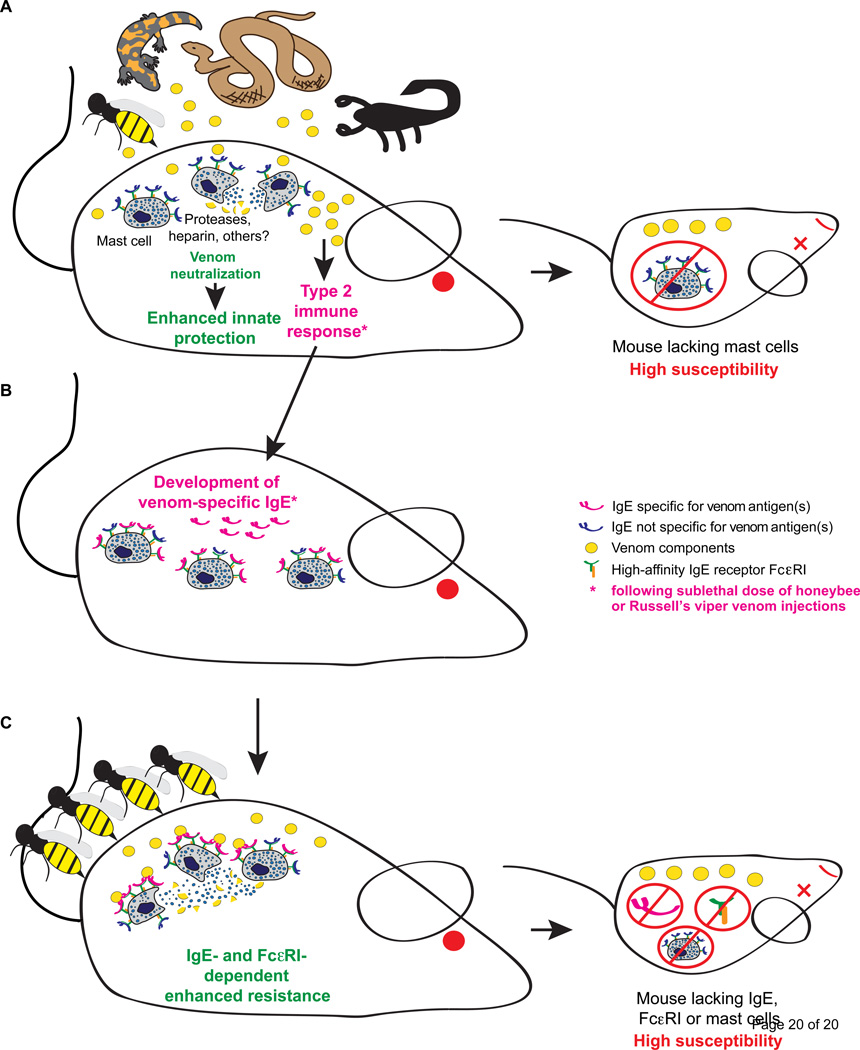

Work done independently in two groups now supports the conclusion that Th2 and IgE-associated immune responses can enhance resistance to whole BV [17] and bvPLA2 [39]. We think that this likely reflects, at least in part, the ability of MCs bearing on their surface venom-specific IgE antibodies to respond more rapidly and perhaps more extensively to encounters with venom than do MCs which can respond to these venoms solely by innate mechanisms. Such venom-IgE-sensitized MCs also can be activated by lower concentrations of venom than are needed to induce degranulation of naïve MCs [17]. Once MCs have been activated, whether by innate or IgE-dependent mechanisms (or by a combination of these mechanisms) and MC proteases and other granule contents have been exteriorized, then these mediators work according to chemical rules (e.g., based on the substrate specificity of the released enzymes) in an immunologically non-specific fashion to identify and degrade toxic components of the venom (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Innate and IgE/ FcεRI-dependent activation of mast cells by venom components can enhance resistance to a potentially lethal dose of whole venoms.

(A) MCs can enhance innate resistance of mice to the morbidity and mortality induced by the whole venoms of the honeybee, three species of snakes (Israeli Mole Viper, Western diamondback rattlesnake, and Southern copperhead), the Gila monster lizard, and two species of scorpions through mechanisms that depend on the release of mediators that can neutralize toxic components of venoms.

(B) Injection of a sub-lethal dose of honeybee (BV) or Russell's viper venom (RVV) induces an adaptive type 2 immune response in mice that is associated with development of IgE antibodies that can increase the resistance of mice to a potentially lethal dose of the same venom. (C) The protective effect of the type 2 immune response against BV is mediated by IgE antibodies, FcεRI and mast cells.

In principle, IgE-enhanced recruitment of MC proteases, and other MC mediators which may have beneficial effects in countering the activities of multiple venom toxins, can occur even if the Th2 response induced by venoms results in the development of IgE antibodies specific for only some of the venom components: once MCs have been activated, the released proteases can degrade multiple venom components, not just the ones recognized by IgE. Moreover, such MC mediator-dependent neutralization of venom components may occur both locally at the site of envenomation and, in highly envenomated animals, perhaps systemically. Indeed, in the latter situation, the induction of IgE-dependent “anaphylaxis” (i.e., a strong systemic response induced by the activation of MCs in multiple anatomic compartments) may help to ensure that toxins distributed by the circulation beyond the site of envenomation also can be degraded by MC-derived proteases. From that perspective, perhaps even anaphylaxis can in some cases be “protective”, assuming of course that one survives it.

What next? We are only at the beginning of efforts to understand the beneficial roles of MCs and IgE in enhancing host resistance to venoms and other potentially toxic environmental challenges. There are many questions to answer. In how many ways can the immune response detect such challenges? Can other MC-derived mediators, beyond proteases and perhaps heparin, confer benefit in such settings? Can IgE enhance adaptive resistance to venoms by mechanisms other than those involving MCs? And what are the genetic or environmental factors which determine whether envenomated animals develop a propensity to exhibit anaphylaxis to tiny amounts of venom (amounts that would not intrinsically induce serious pathology) as opposed to a “protective” response that can help the host to resist the toxicity associated with large amounts of such venom [9–12]? It is well known that some individuals develop Th2 responses to specific venoms (such as BV) without exhibiting allergic reactions to that venom [45], and there is much evidence that Th2 responses are subject to intricate immune regulation that can down-regulate IgE-dependent reactivity to the inducing antigen [46], including BV [47–49]. Delineating the mechanisms underlying the development of potentially “anaphylactic” vs. “protective” Th2 immune responses, and the mechanisms which account for the innate and adaptive functions of MCs and IgE that enhance resistance to venom, may help in the development of better protocols for venom immunotherapy and in the prevention of catastrophic anaphylactic reactions to environmental substances, as well as in the design of improved therapeutics to treat envenomated people and other animals.

Highlights.

Mast cell activation can contribute to innate immunity to multiple animal venoms.

Mast cell granule-associated proteases can degrade toxic components of venoms.

Th2 immune responses can enhance survival in mice injected with certain venoms.

IgE and FcεRI can be key elements of acquired Th2 immune resistance to venom.

IgE-dependent mast cell activation can contribute to acquired resistance to venoms.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Galli laboratory for discussions. T.M. was supported by a Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship for Career Development: European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7-PEOPLE-2011-IOF), 299954, and a "Charge de recherches" fellowship of the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research (F.R.S-FNRS). P.S. was supported by a Max Kade Fellowship of the Max Kade Foundation and the Austrian Academy of Sciences and a Schroedinger Fellowship of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF): J3399-B21; M.T. and S.J.G. were supported by the Department of Pathology at Stanford University and National Institutes of Health grants AI023990, CA072074, AI070813, AR067145 and U19 AI10429 (to S.J.G.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

An annotated bibliography with comments about some of the same articles which are cited and commented on in this review is scheduled to appear in the October, 2015 issue of Experimental Dermatology, to accompany a lecture that will be given by Stephen J. Galli at a meeting organized by the Fondation René Touraine, on "Mast cells and urticaria", that will be held in Paris, France, on December 4, 2015.

References

- 1. Akahoshi M, Song CH, Piliponsky AM, Metz M, Guzzetta A, Abrink M, Schlenner SM, Feyerabend TB, Rodewald HR, Pejler G, et al. Mast cell chymase reduces the toxicity of Gila monster venom, scorpion venom, and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4180–4191. doi: 10.1172/JCI46139. ** Studies employing MC-engrafted genetically MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/W-v and C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh mice, as well as mice lacking either the MC chymase, MC protease-4 (MCPT4) or CPA3 enzymatic activity, showed that MCs and MCPT4 (which can degrade helodermin, a peptide in Gila monster [Heloderma suspectum] venom that is structurally similar to mammalian VIP), but not CPA3, can enhance host resistance to the toxicity of Gila monster venom. MCs and MCPT4 also limited the toxicity associated with high concentrations of VIP, and reduced the morbidity and mortality induced by the venoms of the Deathstalker (Yellow) scorpion (Leiurus quinquestriatus hebraeus) and the Arizona bark scorpion (Centruroides exilicauda).

- 2.Higginbotham RD, Karnella S. The significance of the mast cell response to bee venom. J Immunol. 1971;106:233–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Metz M, Grimbaldeston MA, Nakae S, Piliponsky AM, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells in the promotion and limitation of chronic inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2007;217:304–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Metz M, Piliponsky AM, Chen CC, Lammel V, Abrink M, Pejler G, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells can enhance resistance to snake and honeybee venoms. Science. 2006;313:526–530. doi: 10.1126/science.1128877. **In studies employing MC knock-in kit mutant mice (i.e., MC-engrafted genetically MC-deficient WBB6F1-KitW/W-v and C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh mice), the authors provided strong experimental evidence in mice that, as suggested by Higginbotham (see refs. 2 and 14), MCs can enhance resistance to the toxicity of whole venoms, in this case the venoms of three snakes and the honeybee, as well as to the toxicity of a component of the venom of the Israeli mole viper (Atractaspis engaddensis), sarafotoxin 6b. By using a phramacological approach, and by employing shRNA to markedly diminish the content of carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3) in MCs prior to their transfer into genetically MC-deficient mice, this study provided evidence that CPA3 is a MC-associated protease that importantly contributes to the MC’s ability to enhance resistance to the toxicity of whole venom from A. engaddensis and to sarafotoxin 6b.

- 5.Metcalfe DD, Baram D, Mekori YA. Mast cells. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:1033–1079. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saelinger CB, Higginbotham RD. Hypersensitivity responses to bee venom and the mellitin. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1974;46:28–37. doi: 10.1159/000231110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charavejasarn CC, Reisman RE, Arbesman CE. Reactions of anti-bee venom mouse reagins and other antibodies with related antigens. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1975;48:691–697. doi: 10.1159/000231356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jarisch R, Yman L, Boltz A, Sandor I, Janitsch A. IgE antibodies to bee venom, phospholipase A, melittin and wasp venom. Clin Allergy. 1979;9:535–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1979.tb02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wadee AA, Rabson AR. Development of specific IgE antibodies after repeated exposure to snake venom. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;80:695–698. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(87)90289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Annila I. Bee venom allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:1682–1687. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reimers AR, Weber M, Muller UR. Are anaphylactic reactions to snake bites immunoglobulin E-mediated? Clin Exp Allergy. 2000;30:276–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilo BM, Rueff F, Mosbech H, Bonifazi F, Oude-Elberink JN. Diagnosis of Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy. 2005;60:1339–1349. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Profet M. The function of allergy: immunological defense against toxins. Q Rev Biol. 1991;66:23–62. doi: 10.1086/417049. ** In this provocative review article, Margie Profet proposed that components of "allergic" host defenses, including mast cells, IgE antibodies and other elements of immune hypersensitivity, rather than being purely deleterious for the host, evolved as defense mechanisms against a large array of environmental toxic substances, including venoms and plant compounds.

- 14. Higginbotham RD. Mast cells and local resistance to Russell's viper venom. J Immunol. 1965;95:867–875. * Higginbotham reported that the venom of the highly poisonous Russell’s viper, which contains cationic toxins, rapidly induced mouse MC degranulation in vivo and that the toxicity of that venom in vivo was significantly diminished by its prior incubation ex vivo with heparin, the highly anionic serglycin proteoglycan stored in MC cytoplasmic granules. These findings suggested that MC-derived heparin may enhance local resistance to Russell's viper venom in mice. Note: this study was conducted many years before the first report of a genetically MC-deficient mouse (Kitamura Y, Go S, Hatanaka K. Decrease of mast cells in W/Wv mice and their increase by bone marrow transplantation. Blood 1978, 52:447–452), so it was not possible for Higginbotham to use such animals to assess definitively the importance of MCs to resistance to Russell’s viper venom in vivo.

- 15.Wernersson S, Pejler G. Mast cell secretory granules: armed for battle. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:478–494. doi: 10.1038/nri3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schneider LA, Schlenner SM, Feyerabend TB, Wunderlin M, Rodewald HR. Molecular mechanism of mast cell mediated innate defense against endothelin and snake venom sarafotoxin. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2629–2639. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071262. ** By creating and testing a transgenic mouse expressing a CPA3 that lacks enzymatic activity, but does not affect expression of other MC proteases, the authors showed that catalytically active carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3) is required to reduce the in vivo toxicity of both the mammalian peptide endothelin-1 (ET-1) and a toxic component of Atractaspis engaddensis venom, sarafotoxin 6b. Biochemical analysis by mass spectrometry showed that CPA3 reduces the toxicity of sarafotoxin 6b by cleaving the peptide’s carboxyl-terminal tryptophan. This work established the precise molecular mechanism by which CPA3 can reduce the toxicity of ET-1 and sarafotoxin 6b.

- 17. Marichal T, Starkl P, Reber LL, Kalesnikoff J, Oettgen HC, Tsai M, Metz M, Galli SJ. A beneficial role for immunoglobulin E in host defense against honeybee venom. Immunity. 2013;39:963–975. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.005. ** This study provided the first experimental evidence that an acquired Th2 immune response induced by injection of a sublethal amount of a venom, in this case whole honeybee venom, can increase resistance of mice against the mortality induced by a potentially lethal dose of that venom. It also provided evidence that this enhanced resistance requires IgE antibodies and the FcεRI alpha and gamma chains, and is diminished in mice that genetically lack mast cells. The authors also reported that an acquired Th2 immune response to Russell's viper venom can increase the resistance of mice against the mortality induced by a potentially lethal dose of that venom.

- 18.Lilla JN, Chen CC, Mukai K, BenBarak MJ, Franco CB, Kalesnikoff J, Yu M, Tsai M, Piliponsky AM, Galli SJ. Reduced mast cell and basophil numbers and function in Cpa3-Cre; Mcl-1fl/fl mice. Blood. 2011;118:6930–6938. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurer M, Wedemeyer J, Metz M, Piliponsky AM, Weller K, Chatterjea D, Clouthier DE, Yanagisawa MM, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells promote homeostasis by limiting endothelin-1-induced toxicity. Nature. 2004;432:512–516. doi: 10.1038/nature03085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fry BG. From genome to "venome": molecular origin and evolution of the snake venom proteome inferred from phylogenetic analysis of toxin sequences and related body proteins. Genome Res. 2005;15:403–420. doi: 10.1101/gr.3228405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couvineau A, Laburthe M. VPAC receptors: structure, molecular pharmacology and interaction with accessory proteins. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:42–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fry BG, Roelants K, Champagne DE, Scheib H, Tyndall JD, King GF, Nevalainen TJ, Norman JA, Lewis RJ, Norton RS, et al. The toxicogenomic multiverse: convergent recruitment of proteins into animal venoms. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:483–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuhn-Nentwig L. Antimicrobial and cytolytic peptides of venomous arthropods. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2651–2668. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3106-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palm NW, Medzhitov R. Role of the inflammasome in defense against venoms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1809–1814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221476110. * This study provided evidence that bee venom is detected by the NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3 inflammasome, triggering activation of caspase-1 and the subsequent secretion of IL-1β by macrophages. Activation of the inflammasome by bee venom induced caspase-1–dependent inflammation, including neutrophil recruitment to the site or envenomation, but the inflammasome was dispensable for the allergic response to bee venom. The authors found that caspase-1–deficient mice were more susceptible to the toxicity of bee and snake venoms, suggesting that a caspase-1–dependent innate immune response can enhance resistance to such envenomation.

- 25.Schafer B, Piliponsky AM, Oka T, Song CH, Gerard NP, Gerard C, Tsai M, Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. Mast cell anaphylatoxin receptor expression can enhance IgE-dependent skin inflammation in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tambourgi DV, van den Berg CW. Animal venoms/toxins and the complement system. Mol Immunol. 2014;61:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul WE, Zhu J. How are T(H)2-type immune responses initiated and amplified? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:225–235. doi: 10.1038/nri2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galli SJ, Tsai M. IgE and mast cells in allergic disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:693–704. doi: 10.1038/nm.2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pulendran B, Artis D. New paradigms in type 2 immunity. Science. 2012;337:431–435. doi: 10.1126/science.1221064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holgate ST, Polosa R. Treatment strategies for allergy and asthma. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:218–230. doi: 10.1038/nri2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Artis D, Maizels RM, Finkelman FD. Forum: Immunology: Allergy challenged. Nature. 2012;484:458–459. doi: 10.1038/484458a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Portier MM, Richet C. De l'action anaphylactique de certains venims. C R Soc Biol. 1902;54:170–172. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkelman FD. Anaphylaxis: lessons from mouse models. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:506–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.033. quiz 516-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finkelman FD, Shea-Donohue T, Morris SC, Gildea L, Strait R, Madden KB, Schopf L, Urban JF., Jr Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated host protection against intestinal nematode parasites. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:139–155. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stetson DB, Voehringer D, Grogan JL, Xu M, Reinhardt RL, Scheu S, Kelly BL, Locksley RM. Th2 cells: orchestrating barrier immunity. Adv Immunol. 2004;83:163–189. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)83005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzsimmons CM, Dunne DW. Survival of the fittest: allergology or parasitology? Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:447–451. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stebbings JH., Jr Immediate hypersensitivity: a defense against arthropods? Perspect Biol Med. 1974;17:233–239. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1974.0027. ** In this review article, Stebbings proposed that a major function of immediate hypersensitivity reactions is the protection of terrestrial vertebrates from the bites of, or invasion by, arthropods. To our knowledge, this is the first article to propose such a beneficial role of immediate hypersensitivity.

- 38. Palm NW, Rosenstein RK, Medzhitov R. Allergic host defences. Nature. 2012;484:465–472. doi: 10.1038/nature11047. * In this scholalry perspective article, Medzhitov and colleagues presented arguments to support the hypothesis that the allergic module of immunity may have an important role in host defence against noxious environmental substances, adding additional arguments and evidence in favor of the "toxin hypothesis" of allergies proposed by Margie Profet in 1991 (ref. 13, above).

- 39. Palm NW, Rosenstein RK, Yu S, Schenten DD, Florsheim E, Medzhitov R. Bee venom phospholipase A2 induces a primary type 2 response that is dependent on the receptor ST2 and confers protective immunity. Immunity. 2013;39:976–985. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.006. ** This study provided evidence that bee venom phospholipase A2 (bvPLA2) can induce type 2 innate and adaptive immune responses in mice via enzymatic cleavage of phospholipids, release of IL-33 and ST2-dependent activation of ILC2 cells. It also reported that the bvPLA2-specific type 2 response can confer protection against what was characterized (by assessment of body temperature) as a near lethal dose of bvPLA2 via FcεRI-dependent mechanisms.

- 40.Habermann E. Bee and wasp venoms. Science. 1972;177:314–322. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4046.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dudler T, Machado DC, Kolbe L, Annand RR, Rhodes N, Gelb MH, Koelsch K, Suter M, Helm BA. A link between catalytic activity, IgE-independent mast cell activation, and allergenicity of bee venom phospholipase A2. J Immunol. 1995;155:2605–2613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinet JP. The high-affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilon RI): from physiology to pathology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:931–972. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oettgen HC, Geha RS. IgE in asthma and atopy: cellular and molecular connections. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:829–835. doi: 10.1172/JCI8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivera J, Fierro NA, Olivera A, Suzuki R. New insights on mast cell activation via the high affinity receptor for IgE. Adv Immunol. 2008;98:85–120. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)00403-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Antonicelli L, Bilo MB, Bonifazi F. Epidemiology of Hymenoptera allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:341–346. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akdis CA, Akdis M. Advances in allergen immunotherapy: Aiming for complete tolerance to allergens. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:280ps286. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muller UR. Bee venom allergy in beekeepers and their family members. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;5:343–347. doi: 10.1097/01.all.0000173783.42906.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meiler F, Zumkehr J, Klunker S, Ruckert B, Akdis CA, Akdis M. In vivo switch to IL-10-secreting T regulatory cells in high dose allergen exposure. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2887–2898. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozdemir C, Kucuksezer UC, Akdis M, Akdis CA. Mechanisms of immunotherapy to wasp and bee venom. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1226–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]