Abstract

Background

Nationwide skin cancer screening was introduced in Germany in 2008. The positive results of a pilot project carried out in 2003–4 in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein had implied that screening would lower the mortality from melanoma.

Methods

Data on the incidence of invasive malignant melanoma of the skin (MM; ICD-10: C43) were extracted from the databases of the Association of Population-based Cancer Registries in Germany (GEKID) and from the Schleswig-Holstein cancer registry. Mortality rates were extracted from the official cause-of-death statistics.

Results

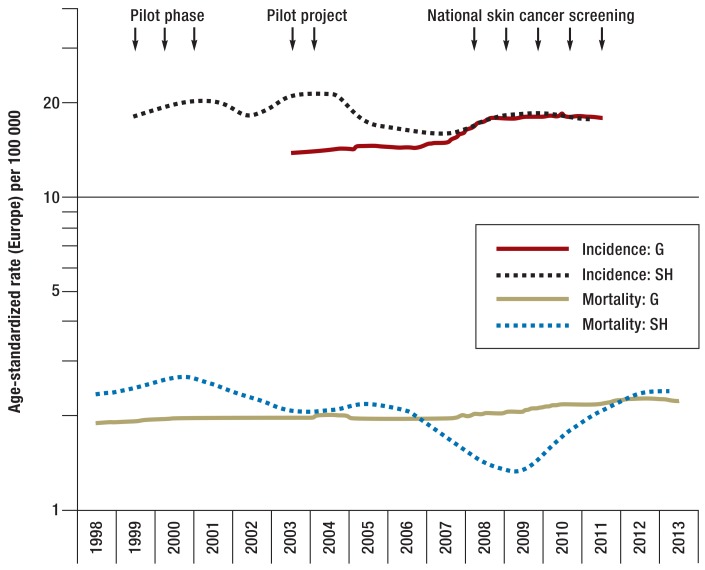

With the beginning of nationwide screening in 2008, the age-standardized incidence rate in Germany increased by approximately 28% to 18.2 cases per 100 000 persons in 2010. In Schleswig-Holstein, the incidence fell after the pilot project ended and has been comparable to the nationwide incidence since 2008. For Germany overall, there has been no downward trend in MM mortality since the introduction of nationwide screening; in 2013, the mortality rate was 2.3 deaths per 100 000 persons per year. In the area of the pilot study, mortality declined to a level of 1.0/100 000/year until 2008 and then began to rise again. At present, the mortality due to MM in Schleswig-Holstein is once again the same as that in Germany overall (2.4/100 000/year).

Conclusion

The introduction of nationwide skin cancer screening in 2008 has not yet led to any measurable decline in mortality due to melanoma. The current method of screening seems to be less thorough than that used in the pilot project; this may explain the absence of a decline in MM-related mortality in Germany overall up to the year 2013, as well as the rising mortality in Schleswig-Holstein since the end of the pilot program. The generation of a robust set of data on how skin cancer screening can be optimized now seems urgently necessary.

Malignant melanoma (MM), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) are the three most common forms of skin cancer. Combined, they make skin cancer the most common cancer in Germany. The Robert Koch Institute forecast around 20 000 new cases of malignant melanoma for 2014. In addition, 150 000 new cases of basal cell carcinoma and 37 000 of squamous cell carcinoma were expected. This is a total of at least 200 000 new cancers (1). These figures are for first skin cancers; as skin cancer often occurs multiple times in a single individual, the number of cases requiring treatment may be substantially higher (2).

Early detection of skin cancer has been a fixed part of the German early cancer detection guidelines since 1974. Initially, it simply took the form of a question regarding skin abnormalities (3). The development of skin cancer screening in Germany began in 1999 in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein. Following some initial pilot screening in 2001, a feasibility study of population-wide skin cancer screening began in 2003: from July 2003 to June 2004, two-tier skin cancer screening was made available in Schleswig-Holstein (the SCREEN project) (4). Around 360 000 individuals underwent full-body visual inspection. The almost 1800 physicians who participated in the project underwent a compulsory eight-hour training program. A total of 3103 skin tumors were documented during screening, of which 585 were malignant melanomas, 1961 basal cell carcinomas, and 392 squamous cell carcinomas. The screening resulted in more favorable population-based stage distribution of diagnosed malignant melanomas (5). Between 1999 and 2009 there was an almost 50% decrease in melanoma mortality. Comparison of this trend with adjacent regions showed that a decrease in melanoma mortality was seen only in the region covered by screening (6).

Nationwide skin cancer screening was introduced in Germany in mid-2008. From the age of 35 years onwards, every individual with statutory health insurance is now entitled to full-body visual inspection of the skin at two-year intervals. When this was introduced, quality evaluation of the process and structure of screening was to be performed five years later (7). This evaluation was recently published but does not include effectiveness evaluation (8). By now more up-to-date incidence and mortality figures have become available, and these can be used for an initial evaluation of the effectiveness of national skin cancer screening in Germany.

Methods

Evaluation of effectiveness (in this case, reduction in mortality) was based on available incidence and mortality rates and comparison with the Schleswig-Holstein pilot project (observational study with time series analysis). As malignant melanoma accounts for approximately 80% of skin cancer deaths, analyses were limited to malignant melanoma only. The incidence rates of invasive malignant melanoma (ICD-10: C43) used are the current estimates of the Association of Population-based Cancer Registries in Germany (GEKID, Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e. V.); data is available for the years 2003 to 2011 for Germany (9). Figures for Schleswig-Hosltein were extracted from the database of the regional population-based cancer registry for the years 1999 to 2011 (10).

The German Federal Statistical Office publishes full information on all deaths in Germany every year in its official statistics on causes of death. This was the source of the mortality figures for malignant melanoma up to 2013 (11); new population census data (2011) were used for 2011 to 2013.

Incidence and mortality are shown as rates standardized for age according to the European standard. For better visual representation of trends in incidence and mortality, a logarithmic scale has been used for the y-axis, and mortality figures are shown in the form of a three-year moving average.

Results

In the pilot region, Schleswig-Holstein, the malignant melanoma incidence rate rose first during the pilot phase and then during the SCREEN pilot project (Figure, Table). After the project ended, incidence fell and then rose again slightly following introduction of nationwide screening. For Germany as a whole, the incidence rate for malignant melanoma remained steady until 2008 (between 14.0 and 14.9 per 100 000 between 2003 and 2007). During this period, the incidence rate was a mean of 21% lower than in Schleswig-Holstein. When nationwide screening began, the malignant melanoma incidence rate in Germany overall increased by around 28% (2003/4 versus 2010/11) and is now almost exactly the same as in Schleswig-Holstein. Absolute case numbers are shown in eTable 1.

Figure.

Malignant melanoma incidence and mortality in Germany and Schleswig-Holstein, male and female combined, rate standardized for age according to the European standard per 100 000, logarithmic representation, mortality shown as moving average.

Data sources: mortality: www.gbe-bund.de; incidence for Germany (G): www.gekid.de; incidence for Schleswig-Holstein (SH): www.krebsregister-sh.de

Table. Malignant melanoma incidence and mortality in Germany and Schleswig-Holstein, by year and sex*.

| Incidence (ASR/100000) | Mortality (ASR/100000) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Schleswig-Holstein | Germany | Schleswig-Holstein | |||||||||

| Year | M | F | T | M | F | T | M | F | T | M | F | T |

| 1998 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | ||||||

| 1999 | 16.5 | 19.1 | 17.8 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 2.6 | |||

| 2000 | 20.6 | 18.8 | 19.7 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 2.6 | |||

| 2001 | 18.9 | 22.0 | 20.5 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 2.2 | 2.8 | |||

| 2002 | 17.0 | 18.8 | 17.9 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 2.2 | |||

| 2003 | 13.6 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 18.3 | 24.0 | 21.1 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 2004 | 14.4 | 13.9 | 14.2 | 20.4 | 22.1 | 21.3 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

| 2005 | 14.6 | 14.4 | 14.5 | 17.3 | 17.2 | 17.2 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| 2006 | 14.4 | 14.2 | 14.3 | 16.2 | 15.7 | 15.9 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 2.2 |

| 2007 | 14.9 | 14.9 | 14.9 | 15.3 | 16.2 | 15.7 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| 2008 | 18.3 | 17.0 | 17.7 | 15.9 | 19.0 | 17.4 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| 2009 | 18.6 | 17.2 | 17.9 | 18.1 | 18.5 | 18.3 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| 2010 | 18.4 | 18.0 | 18.2 | 17.1 | 18.3 | 17.7 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.5 |

| 2011 | 18.2 | 17.6 | 17.9 | 16.9 | 18.7 | 17.8 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| 2012 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 2.4 | ||||||

| 2013 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.2 | 2.4 | ||||||

Years in which skin cancer screening (pilot project in Schleswig-Holstein or national skin cancer screening) was performed are shaded gray.

*Rates are reported by sex (M: male, F:female, T: total) and were standardized for age according to European standard per 100 000 (ASR: age-standardized rate). Data sources: mortality: www.gbe-bund.de; incidence for Germany: www.gekid.de; incidence for Schleswig-Holstein: www.krebsregister-sh.de

eTable 1. Absolute case numbers for malignant melanoma incidence and mortality in Germany and Schleswig-Holstein, by year and sex.

| Incidence (case number) | Mortality (case number) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Schleswig-Holstein | Germany | Schleswig-Holstein | |||||||||

| Year | M | F | T | M | F | T | M | F | T | M | F | T |

| 1998 | 1026 | 1004 | 2030 | 32 | 45 | 77 | ||||||

| 1999 | 256 | 334 | 590 | 1057 | 964 | 2021 | 51 | 44 | 95 | |||

| 2000 | 324 | 333 | 657 | 1161 | 1017 | 2178 | 54 | 43 | 97 | |||

| 2001 | 307 | 388 | 695 | 1171 | 1046 | 2217 | 57 | 52 | 109 | |||

| 2002 | 275 | 334 | 609 | 1137 | 1073 | 2210 | 43 | 45 | 88 | |||

| 2003 | 6508 | 7483 | 13992 | 309 | 409 | 718 | 1286 | 1009 | 2295 | 35 | 41 | 76 |

| 2004 | 7010 | 7418 | 14428 | 342 | 394 | 736 | 1256 | 1037 | 2293 | 50 | 37 | 87 |

| 2005 | 7240 | 7727 | 14966 | 300 | 332 | 632 | 1238 | 1089 | 2327 | 57 | 29 | 86 |

| 2006 | 7285 | 7702 | 14987 | 288 | 303 | 591 | 1266 | 1021 | 2287 | 53 | 35 | 88 |

| 2007 | 7673 | 8068 | 15740 | 276 | 314 | 590 | 1368 | 1099 | 2467 | 42 | 36 | 78 |

| 2008 | 9547 | 9305 | 18852 | 294 | 367 | 661 | 1365 | 1135 | 2500 | 23 | 21 | 44 |

| 2009 | 9882 | 9371 | 19253 | 344 | 339 | 683 | 1454 | 1203 | 2657 | 33 | 22 | 55 |

| 2010 | 9852 | 9753 | 19605 | 333 | 349 | 682 | 1568 | 1143 | 2711 | 40 | 24 | 64 |

| 2011 | 9875 | 9772 | 19646 | 336 | 365 | 701 | 1709 | 1212 | 2921 | 55 | 49 | 104 |

| 2012 | 1627 | 1248 | 2875 | 55 | 50 | 105 | ||||||

| 2013 | 1787 | 1255 | 3042 | 57 | 55 | 112 | ||||||

Years in which skin cancer screening (pilot project in Schleswig-Holstein or national skin cancer screening) was performed are shaded gray. Data for Germany relates to all German federal states, including Schleswig-Holstein.Rates are reported by sex (M: male, F: female, T: total) Data sources: mortality: www.gbe-bund.de; incidence for Germany: www.gekid.de; incidence for Schleswig-Holstein: www.krebsregister-sh.de

Before the year 2000, malignant melanoma mortality was approximately 25% higher in Schleswig-Holstein than in Germany as a whole. When the pilot project began, mortality in Schleswig-Holstein fell to below the value for Germany, reaching its lowest point in 2008 (50% lower than the figure for Germany). Mortality subsequently rose again and is now once more somewhat higher than the mean value for Germany overall. These trends can be observed for both sexes and all age groups (eTable 2). For Germany as a whole, in contrast, no decrease in malignant melanoma mortality can be detected: on the contrary, it rose slightly during the period in question. This was the case among women and even more so among men. The increase was confined almost exclusively to those aged over 64 years (eTable 2).

eTable 2. Raw malignant melanoma mortality rates for Germany and Schleswig-Holstein, by year and sex.

| Germany (per 100000) | Schleswig-Holstein (per 100000) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||||||||

| Year | 35 to 49 | 50 to 64 | 65+ | 35 to 49 | 50 to 64 | 65+ | 35 to 49 | 50 to 64 | 65+ | 35 to 49 | 50 to 64 | 65+ |

| 1998 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 10.5 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 7.7 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 9.1 | 2.1 | 3.2 | 10.5 |

| 1999 | 1.6 | 4.2 | 10.3 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 7.3 | 3.3 | 6.7 | 12.3 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 9.7 |

| 2000 | 1.6 | 4.6 | 11.1 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 7.7 | 2.9 | 7.8 | 11.8 | 0.7 | 3.9 | 10.6 |

| 2001 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 11.3 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 8.0 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 17.7 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 13.2 |

| 2002 | 1.4 | 4.2 | 10.9 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 8.1 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 12.7 | 1.3 | 3.6 | 9.8 |

| 2003 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 12.0 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 7.2 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 11.1 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 8.3 |

| 2004 | 1.4 | 4.3 | 11.8 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 7.4 | 1.2 | 6.3 | 13.3 | 1.8 | 3.7 | 5.8 |

| 2005 | 1.3 | 4.2 | 11.3 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 7.7 | 2.6 | 5.6 | 13.9 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 6.6 |

| 2006 | 1.4 | 4.1 | 11.4 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 7.1 | 1.7 | 6.5 | 12.0 | 1.5 | 3.4 | 6.4 |

| 2007 | 1.5 | 4.5 | 11.9 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 7.6 | 1.1 | 5.4 | 9.6 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 7.5 |

| 2008 | 1.5 | 3.9 | 12.1 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 7.8 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 3.8 |

| 2009 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 13.0 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 8.3 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 3.8 |

| 2010 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 13.8 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 7.8 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 9.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 4.9 |

| 2011 | 1.7 | 4.6 | 16.5 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 8.8 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 14.0 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 9.9 |

| 2012 | 1.3 | 4.4 | 15.8 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 9.1 | 1.6 | 5.3 | 12.6 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 8.7 |

| 2013 | 1.5 | 4.5 | 17.3 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 9.3 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 13.5 | 1.9 | 3.7 | 10.9 |

Years in which skin cancer screening (pilot project in Schleswig-Holstein or national skin cancer screening) was performed are shaded gray.

Data for Germany relates to all German federal states, including Schleswig-Holstein.Rates are reported by sex (M: male, F: female, T: total) and age groups (35 to 49 years, 50 to 64 years, 65+ years) Data source: www.gbe-bund.de

Discussion

The availability of data on the effectiveness of skin cancer screening remains limited. Although the current S3 guideline on skin cancer prevention (12) evaluates the decrease in mortality resulting from skin cancer screening with level of evidence 2+, the systematic search of the literature on the subject uncovered only one study: the observational study from the Schleswig-Holstein pilot project mentioned above (4). A systematic review on skin cancer screening which is currently in progress (13) already shows that there is currently no higher-quality evidence from randomized controlled trials on skin cancer screening (oral communication by the project leader following the end of abstract screening in March 2015). A randomized controlled trial in Australia (SkinWatch, which consisted of information and training for the public, training for physicians, and provision of access to examinations in skin screening clinics) led to an increase in full-body inspections. However, as a result of its limited time span the study was unable to investigate an effect on morbidity or mortality (14).

This means that for the foreseeable future there are no high-quality studies on the effectiveness of skin cancer screening. All the available evidence comes from observational studies (such as the SCREEN project mentioned above) and a French study published very recently. This study evaluates the effect of a training program for primary care and other physicians in the Champagne-Ardenne region on stage-specific melanoma incidence. The Doubs and Belfort region, where no training had been implemented, was used for comparison. In the region covered by the intervention, the incidence rate of “very thick melanoma” (defined as Breslow ≥3 mm) standardized for age, which is a good surrogate parameter for subsequent melanoma mortality, fell from 1.07 per 100 000 before the intervention to 0.71 per 100 000 after it. The stage-specific incidence rate in the comparator region remained almost unchanged (15).

The effectiveness of the current national skin cancer screening program is almost impossible to infer, as it has not yielded valid data; so concludes the most recently published evaluation report of the German Federal Joint Committee (GBA, Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss) on skin cancer screening (8). Even the simplest information, such as reliable annual participation rates, is unavailable. Although there are estimated participation rates based on insurers’ data or surveys (8, 16– 18), the figures they provide, up to 30% in two years, should be seen only as a crude estimate. To date, the only reliable source of data for the evaluation of current skin cancer screening in Germany is the official data of the cancer registry and cause-of-death statistics. Until more, reliable data becomes available, the effects of skin cancer screening can be judged only approximately.

The decrease in mortality when screening within the pilot project was begun has been comprehensively described and discussed (6). In addition to screening, the authors discuss a wide variety of potential causes of the decrease in mortality in the pilot region (e.g. reinforced primary prevention, better treatment, coding of causes of death, etc.). Other than chance, which cannot be ruled out (even in randomized controlled trials), only screening remained as a potential reason for the drop in mortality. However, the authors also conclude that the purely observational nature of the analyses makes it impossible to determine which part of the complex skin cancer screening intervention (training, publicity, or full-body inspection) is responsible for the decrease.

Now, almost seven years after the introduction of the national screening program, there are two essential questions:

Why has mortality not yet decreased in Germany as a whole when there was such a swift decrease in the pilot region?

Why has mortality in the pilot region risen again?

One reason that might explain the absence as yet of a decrease in malignant melanoma mortality in Germany may simply be that it is still too soon to expect any effect from screening. In Schleswig-Holstein screening was preceded by a pilot phase of approximately five years; this may itself have affected mortality. Simulation analyses (19) and the swift decrease in mortality in Schleswig-Holstein, however, would lead one to expect at least a slight change five years after the introduction of nationwide screening. As there is absolutely no such trend observable to date (the increase in mortality rates in 2011 to 2013 is partly due to the current census, which has lower population figures), one issue that must be discussed is whether current skin cancer screening may be less intensive than screening during the pilot project in Schleswig-Holstein. This hypothesis is supported by various types of evidence, described below.

Different age groups in screening—In the pilot project screening was available from the age of 20 years upwards. Approximately 20% of participants were aged between 20 and 34 years. Current skin cancer screening does not begin until the age of 35 years. This suggests that screening in the pilot region was more intensive, although the effect of this is probably rather limited, as melanoma mortality is low in younger age groups.

Screening procedure—If the physician performing primary screening as part of national skin cancer screening detects an abnormal finding, he/she must refer the patient to a dermatologist. This was also the case in the pilot project. In addition, however, in the SCREEN project individuals who were not suspected of having skin cancer but did have risk factors for it were also referred to a dermatologist. For 85% of patients referred to dermatologists, the reason for the referral was the risk assessment by the physician who performed primary screening (4). This suggests that screening was more intensive in the pilot region.

Screening physicians—In addition to dermatologists and primary care physicians/internists, other groups of physicians also took part in the pilot project. In total, 1789 (116 dermatologists, 1673 nondermatologists) of 2732 (65%) of all physicians in private practice were involved in screening (4). In national screening, other than dermatologists in private practice only primary care physicians are authorized (7). Although these represent a total of 54% of all physicians in private practice in Germany (4237 dermatologists and 74 474 nondermatologists, of 145 933 physicians who work with outpatients) (20), it cannot be assumed that all of them applied for authorization to conduct skin cancer screening. According to the figures of the Dermatology Prevention Working Group (Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatologische Prävention), 38 000 doctors have qualified for screening. This would correspond to approximately 26% of all physicians in private practice (21). Overall, these figures indicate that screening was more intensive in the pilot region.

Publicity—The pilot project was accompanied by an intensive, professional, public information campaign (18). This included posters, newspaper advertisements, flyers, radio spots, and other measures. No such measures accompanied the launch of national screening. This point should be examined further. In the pilot project, an unusually high percentage of screening participants had risk factors for skin cancer; older at-risk men were particularly likely to take part (4, 22). Publicity measures may make people with risk factors for skin cancer more likely to attend screening. Further evaluation of this hypothesis would require data on the risk profiles of national screening participants. However, the intensive publicity undertaken suggests that screening in the pilot region was more intensive and more targeted.

Incidence of malignant melanoma—Closer examination of the malignant melanoma incidence rate suggests that screening was more intensive in Schleswig-Holstein up to 2004 than in Germany as a whole. During the SCREEN project, malignant melanoma incidence in Schleswig-Holstein increased to a high of 24.0 per 100 000 in women and 20.4 per 100 000 in men. This is substantially higher than the highest figure during national screening (18.0 and 18.6 respectively per 100 000). In addition, after the pilot project ended the incidence rate decreased and is now, during the current national screening, almost exactly the same as the rate for Germany as a whole. The high incidence rates for malignant melanoma in Schleswig-Holstein up to 2004 should therefore be interpreted as representing an intensive, multifactorial intervention to detect skin cancer early. After the end of this intervention, the incidence rate in Schleswig-Holstein moved closer to the national incidence rate. However, the substantial increase in the melanoma incidence rate nationwide when skin cancer screening began (an almost 30% increase) is interesting. One can speculate that the training that had begun may have increased skin cancer reporting rates, and that this can partly explain the increase. The fact that the Germany-wide incidence rate for malignant melanoma and the figure for Schleswig-Holstein are now almost identical also suggests this. This indicates that registration of malignant melanoma is more uniform across Germany.

Participation rates—The lack of reliable data makes it impossible to demonstrate whether the national skin cancer screening participation rate is higher, indicating more intensive screening, than in the pilot project. Rates of 15 to 25% (8), approximately 25% (18), and up to around 30% (16, 17) are cited for various locations for a two-year period. Thus, while the participation rate in the pilot project in Schleswig-Holstein reached almost 20% of the population in just one year (corresponding to 40% in two years), the participation rate for Germany as a whole remains greatly obscured.

Conclusion

In view of all the points mentioned above, the following conclusion seems justified: national skin cancer screening, which has been offered to those over the age of 35 years with statutory health insurance since 2008 in Germany, is less intensive than skin cancer screening in the pilot region was.

In addition to the points already discussed, there may be further factors that make national screening less intensive. For example:

Full-body inspection may be of poorer quality and less consistently performed.

The system for referral of suspected cases by primary care physicians to dermatologists may not be functioning optimally.

It is possible that the two-year gap between screening sessions is not being respected.

The program may be reaching fewer people at high risk of dying of melanoma.

The lack of data means that these potential causes can be neither confirmed nor refuted. However, they should be addressed when skin cancer screening is evaluated. If the hypothesis of national screening being less intensive than the pilot project is accepted, this explains the changes in malignant melanoma mortality observed in the pilot region. Intensive, complex screening leads to a drop in mortality. If this change is reversible (which is a criterion for causality), mortality must rise again if more intensive screening is discontinued and, after a time interval of four years, replaced by less effective screening.

Finally, the unsatisfactory absence of an effectiveness evaluation of the national skin cancer screening program needs mentioning. Despite the open letters and statements by the German Society for Epidemiology (DGEpi, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Epidemiologie), the German Society for Medical Information Technology, Biometrics, and Epidemiology (GMDS, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Medizinische Informatik, Biometrie und Epidemiologie), the Dermatology Prevention Working Group (ADP, Arbeitsgemeinschaft Dermatologische Prävention), and the Association of Population-based Cancer Registries in Germany (GEKID, Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland), the responsible bodies failed to implement an accompanying evaluation system, or implementation of such evaluation was not wanted, when skin cancer screening was introduced (23, 24). Given the costs of skin cancer screening (approximately €131 million per year according to the Federal Joint Committee’s report), 0.5% of this would be sufficient for the sensible suggestions made in the Committee’s report to be implemented in the future, and in addition to establish independent epidemiological evaluation as part of the national cancer plan (see target paper 3 [25]). The current figures and the report submitted by the Federal Joint Committee now provide urgent grounds for scrutinizing the current skin cancer screening program more closely.

Key Messages.

Following a year-long pilot project in Schleswig-Holstein in 2003 to 2004, national skin cancer screening was introduced in Germany in 2008.

Five years after the introduction of national skin cancer screening, there has not yet been a detectable decrease in skin cancer mortality in Germany; nationwide, the figure for 2013 was a total of 2.3 per 100 000.

After the pilot project in Schleswig-Holstein ended, and thus after four years with no skin cancer screening, melanoma mortality—which had initially fallen—rose again to its original level of 2.4 per 100 000.

The national skin cancer screening program is probably substantially less intensive than screening in the pilot project. This may explain why melanoma mortality in Germany has not fallen and why mortality in the pilot region has risen again.

Data collation for this study was completed in 2013. It is possible that mortality will decrease in the next few years.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Katalinic has received reimbursement of conference fees and travel and accommodation expenses from BMS and MSD. He has received fees for preparing scientific training courses from BMS.

PD Waldmann and Dipl.-Stat. Eisemann declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Krebs in Deutschland 2009/2010 9. ed Berlin Robert Koch-Institut und die Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. 2013. www.rki.de/Krebs/DE/Content/Publikationen/Krebs_in_Deutschland/kid_2013/krebs_in_deutschland_2013.pdf; jsessio nid=0BE7FFCB4020E20CEE977217CD5A350B.2_ cid298?__blob=publicationFile. (last accessed on 12 July 2015)

- 2.Marcil I, Stern RS. Risk of developing a subsequent nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer: a critical review of the literature and meta-analysis. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1524–1530. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.12.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.KBV. Krebsfrüherkennungsrichtlinie 1974. www.kbv.de/media/sp/1974_12_16_KFE_Neufassung_RL_BAnz.pdf. (last accessed on 25 February 2015)

- 4.Breitbart EW, Waldmann A, Nolte S, et al. Systematic skin cancer screening in Northern Germany. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eisemann N, Waldmann A, Katalinic A. Inzidenz des malignen Melanoms und Veränderung der stadienspezifischen Inzidenz nach Einführung eines Hautkrebsscreenings in Schleswig-Holstein. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2014;57 doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1876-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katalinic A, Waldmann A, Weinstock MA, et al. Does skin cancer screening save lives? - An observational study comparing trends in melanoma mortality in regions with and without screening. Cancer. 2012;118 doi: 10.1002/cncr.27566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GBA. Krebsfrüherkennungs-Richtlinien (Hautkrebs-Screening) www.g-ba.de/informationen/beschluesse/516/ (last accessed on 4 May 2015)

- 8.Veit C, Lüken F, Melsheimer O. Evaluation der Screeninguntersuchungen auf Hautkrebs gemäß Krebsfrüherkennungs-Richtlinie des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses - Abschlussbericht 2009-2010. BQS Institut für Qualität und Patientensicherheit GmbH, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schätzung der Krebsinzidenz für Deutschland. www.gekid.de. Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e.V. www.gekid.de/Atlas/CurrentVersion/Inzidenz/atlas.html. (last accessed on 18 June 2015)

- 10.Online-Datenbank zur Krebsinzidenz in Schleswig-Holstein. www.krebsregister-sh.de:KrebsregisterSchleswig-Holstein. www.krebsregister-sh.de/datenbank/index.html. (last accessed on 25 February 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Todesursachenstatistik Melanom 1998-2013. www.gbe-bund.de: Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. www.gbe-bund.de/oowa921-install/servlet/oowa/aw92/WS0100/_XWD_PROC?_XWD_2/2/XWD_CUBE.DRILL/_XWD_30/D.954/14643. (last accessed on 25 February 2015)

- 12.S3-Leitlinie Prävention von Hautkrebs, Langversion 1.1, 2014, AWMF Registernummer: 032/052OL. www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Leitlinien.7.0.html. (last accessed on 17 May 2015)

- 13.Versorgungsforschung Deutschland Datenbank. www.versorgungsforschung-deutschland.de/show.php?kennung=VfD_14_003560. (last accessed on 17 May 2015)

- 14.Aitken JF, Youl PH, Janda M, Lowe JB, Ring IT, Elwood M. Increase in skin cancer screening during a community-based randomized intervention trial. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1010–1016. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grange F, Woronoff AS, Bera R, et al. Efficacy of a general practitioner training campaign for early detection of melanoma in France. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:123–129. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Augustin M, Stadler R, Reusch M, Schafer I, Kornek T, Luger T. Skin cancer screening in Germany - perception by the public. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:42–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breitbart EW, Choudhury K, Anders MP, et al. Benefits and risks of skin cancer screening. Oncol Res Treat. 2014;37:38–47. doi: 10.1159/000364887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anders MP, Nolte S, Waldmann A, et al. The German SCREEN project - design and evaluation of the communication strategy. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25:150–155. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisemann N, Waldmann A, Garbe C, Katalinic A. Development of a microsimulation of melanoma mortality for evaluating the effectiveness of population-based skin cancer screening. Med Decis Making. 2015;35:243–254. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14543106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bundesärztekammer. Ergebnisse der Ärztestatistik zum 31. Dezember 2013. www.bundesaerztekammer.de/page.asp?his=0.3.12002. (last accessed on 4 May 2015)

- 21.ADP. www.hautkrebs-screening.de. (last accessed on 4 May 2015)

- 22.Waldmann A, Nolte S, Weinstock MA, et al. Skin cancer screening participation and impact on melanoma incidence in Germany-an observational study on incidence trends in regions with and without population-based screening. Br J Cancer. 2012;106 doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becher H. Stellungnahme der DGEpi zur Einführung des Hautkrebsscreenings. www.dgepi.de/berichte-und-publikationen/stellungnahmen.html. 2007 (last accessed on 29 April 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhn KA, Hoffmann W, Bickeböller H, Becher H. Stellungnahme der GMDS zur Einführung des Hautkrebsscreenings. www.dgepi.de/berichte-und-publikationen/stellungnahmen.html. 2018 (last accessed on 18 June 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. Nationaler Krebsplan. Handlungsfeld 1: Weiterentwicklung der Krebsfrüherkennung. Ziel 3: Evaluation Krebsfrüherkennung. www.bmg.bund.de/fileadmin/dateien/Downloads/N/Nationaler_Krebsplan/Ziel_3_Evaluation_der_Krebsfrueherkennung.pdf2010. (last accessed on 27 May 2015) [Google Scholar]